إستونيا

جمهورية إستونيا Eesti Vabariik (إستونية) | |

|---|---|

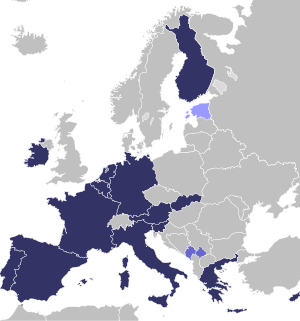

![موقع إستونيا (dark green) – on the European continent (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) — [Legend]](/w/images/thumb/a/a2/EU-Estonia.svg/350px-EU-Estonia.svg.png) موقع إستونيا (dark green) – on the European continent (green & dark grey) | |

| العاصمة و أكبر مدينة | تالين 59°25′N 24°45′E / 59.417°N 24.750°E |

| Official language | Estonian |

| Ethnic groups (2023) | |

| الدين (2021[1]) |

|

| صفة المواطن | Estonian |

| الحكومة | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Alar Karis | |

| Kaja Kallas | |

| التشريع | Riigikogu |

| Independence | |

| 23–24 February 1918 | |

• Joined the League of Nations | 22 September 1921 |

| 1940–1991 | |

| 20 August 1991 | |

• Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 |

| المساحة | |

• الإجمالية | 45،339 km2 (17،505 sq mi) (129thd) |

• الماء (%) | 4.6 |

| التعداد | |

• تقدير 2023 | |

• إحصاء 2021 | 1,331,824[3] |

• الكثافة | 30.6/km2 (79.3/sq mi) (148th) |

| ن.م.إ. (ق.ش.م.) | تقدير 2023 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $61.757 billion[4] (113th) |

• للفرد | ▲ $46,385 [4] (40th) |

| ن.م.إ. (الإسمي) | تقدير 2023 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $41.55 billion[4] (102th) |

• للفرد | ▲ $31,207[4] (37th) |

| جيني (2021) | ▲ 30.6[5] medium |

| م.ت.ب. (2021) | ▲ 0.890[6] very high · 31st |

| العملة | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| التوقيت | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

• الصيفي (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| جانب السواقة | right |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +372 |

| النطاق العلوي للإنترنت | .ee |

| |

إستونيا Estonia (/ɛˈstoʊniə/ (![]() استمع);[7][8] الإستونية: [Eesti] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [ˈeːsti])، رسمياً جمهورية إستونيا (الإستونية: [Eesti Vabariik] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))، هي بلد في منطقة البلطيق بشمال أوروپا. يحدها من الشمال خليج فنلندا، ومن الغرب بحر البلطيق، ومن الجنوب لاتڤيا (343 كم)، ومن الشرق بحيرة پيپوس وروسيا (338.6 كم).[9] عبر بحر البلطيق تقع السويد في الغرب وفنلندا في الشمال. تتألف أراضي إستونيا من البر الرئيسي وأكثر من 1500 جزيرة صغيرة وكبيرة في بحر البلطيق، ويشغل البر مساحة 45227 كم²، وتتأثر البلاد بالمناخ القاري الرطب.

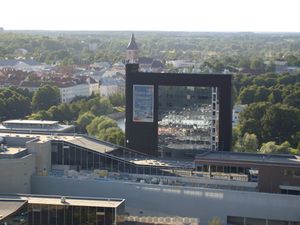

The territory of Estonia consists of the mainland, the larger islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, and over 2,200 other islands and islets on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea,[10] covering a total area of 45،339 متر كيلومربع (17،505 sq mi). The capital city Tallinn and Tartu are the two largest urban areas of the country. The Estonian language is the indigenous and the official language of Estonia; it is the first language of the majority of its population, as well as the world's second most spoken Finnic language.

استمع);[7][8] الإستونية: [Eesti] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [ˈeːsti])، رسمياً جمهورية إستونيا (الإستونية: [Eesti Vabariik] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))، هي بلد في منطقة البلطيق بشمال أوروپا. يحدها من الشمال خليج فنلندا، ومن الغرب بحر البلطيق، ومن الجنوب لاتڤيا (343 كم)، ومن الشرق بحيرة پيپوس وروسيا (338.6 كم).[9] عبر بحر البلطيق تقع السويد في الغرب وفنلندا في الشمال. تتألف أراضي إستونيا من البر الرئيسي وأكثر من 1500 جزيرة صغيرة وكبيرة في بحر البلطيق، ويشغل البر مساحة 45227 كم²، وتتأثر البلاد بالمناخ القاري الرطب.

The territory of Estonia consists of the mainland, the larger islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, and over 2,200 other islands and islets on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea,[10] covering a total area of 45،339 متر كيلومربع (17،505 sq mi). The capital city Tallinn and Tartu are the two largest urban areas of the country. The Estonian language is the indigenous and the official language of Estonia; it is the first language of the majority of its population, as well as the world's second most spoken Finnic language.

The land of what is now modern Estonia has been inhabited by Homo sapiens since at least 9,000 BC. The medieval indigenous population of Estonia was one of the last pagan civilisations in Europe to adopt Christianity following the Papal-sanctioned Livonian Crusade in the 13th century.[11] After centuries of successive rule by the Teutonic Order, Denmark, Sweden, and the Russian Empire, a distinct Estonian national identity began to emerge in the mid-19th century. This culminated in the 24 February 1918 Estonian Declaration of Independence from the then warring Russian and German Empires. Democratic throughout most of the interwar period, Estonia declared neutrality at the outbreak of World War II, but the country was repeatedly contested, invaded and occupied, first by the Soviet Union in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in 1941, and was ultimately reoccupied in 1944 by, and annexed into, the USSR as an administrative subunit (Estonian SSR). Throughout the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation,[12] Estonia's de jure state continuity was preserved by diplomatic representatives and the government-in-exile. Following the bloodless Estonian "Singing Revolution" of 1988–1990, the nation's de facto independence from the Soviet Union was restored on 20 August 1991.

إستونيا هي جمهورية برلمانية ديمقراطية تنقسم إلى خمسة عشر مقاطعة، عاصمتها وأكبر مدنها تالين. بعدد سكان يبلغ 1.3 مليون نسمة، تعتبر واحدة من أقل دول الاتحاد الأوروپي منطقة اليورو، الناتو ومنطقة تشنگن إكتظاظاً بالسكان. الإستونيون هم شعب فنلندي، واللغة الرسمية هي الإستونية، وهي من اللغات الفنلندية الأوگرية شديدة القرب بالفنلندية واللغات السامية، وتختلف بشكل كبير عن المجرية.

كبلد متطور يتمتع باقتصاد متقدم عالي الدخل[13] ومعايير معيشة مترفعة، تحتل إستونية ترتيب متقدم على [[قائمة البلدان حسب مؤشر التنمية البشرية|مؤشر التنمية البشرية] (31 من 191)،[14] sovereign state of Estonia is a democratic unitary parliamentary republic, administratively subdivided into 15 maakond (counties). With a population of just about 1.4 million, it is one of the least populous members of the European Union, the Eurozone, the OECD, the Schengen Area, and NATO. Estonia has consistently ranked highly in international rankings for quality of life,[15] education,[16] press freedom, digitalisation of public services[17][18] and the prevalence of technology companies.[19]

أصل التسمية

إحدى النظريات هي أن الاسم الحديث لإستونيا نشأ من Aesti التي وصفها المؤرخ الروماني تاسيتوس في جرمانيا له (حوالي 98 م).[20]

من ناحية أخرى، الملاحم الإسكندنافية القديمة تشير إلى الأرض ودعا إستلاند، على مقربة من والألمانية الدانمركية والهولندية إستلاند السويدية والنرويجية، الأجل للبلد. النسخ القديمة اللاتينية في وقت مبكر وغيرها من الاسم هي إستيا وهيستيا. [بحاجة لمصدر]

إستونيا كان مشترك الهجاء الإنجليزية البديل قبل الاستقلال.[21][22]

التاريخ

قبل التاريخ وعصر الڤايكنج

Human settlement in Estonia became possible 13,000–11,000 years ago, when the ice from the last glacial era melted. The oldest known settlement in Estonia is the Pulli settlement, on the banks of Pärnu river in southwest Estonia. According to radiocarbon dating, it was settled around 11,000 years ago.[23]

The earliest human habitation during the Mesolithic period is connected to the Kunda culture. At that time the country was covered with forests, and people lived in semi-nomadic communities near bodies of water. Subsistence activities consisted of hunting, gathering and fishing.[24] Around 4900 BC, ceramics appear of the neolithic period, known as Narva culture.[25] Starting from around 3200 BC the Corded Ware culture appeared; this included new activities like primitive agriculture and animal husbandry.[26]

The Bronze Age started around 1800 BC, and saw the establishment of the first hill fort settlements.[28] A transition from hunter-fisher subsistence to single-farm-based settlement started around 1000 BC, and was complete by the beginning of the Iron Age around 500 BC.[23][29] The large amount of bronze objects indicate the existence of active communication with Scandinavian and Germanic tribes.[30]

The middle Iron Age produced threats appearing from different directions. Several Scandinavian sagas referred to major confrontations with Estonians, notably when in the early 7th century "Estonian Vikings" defeated and killed Ingvar, the King of Swedes.[31][بحاجة لمصادر إضافية] Similar threats appeared to the east, where East Slavic principalities were expanding westward. Around 1030 the troops of Kievan Rus led by Yaroslav the Wise defeated Estonians and established a fort in modern-day Tartu. This foothold may have lasted until ca 1061 when an Estonian tribe, the Sosols, destroyed it.[32][33][34][35] Around the 11th century, the Scandinavian Viking era around the Baltic Sea was succeeded by the Baltic Viking era, with seaborne raids by Curonians and by Estonians from the island of Saaremaa, known as Oeselians. In 1187 Estonians (Oeselians), Curonians or/and Karelians sacked Sigtuna, which was a major city of Sweden at the time.[36][37]

وقعت إستونيا على مر التاريخ تحت سيطرة الدانماركيين، والسويديين، والألمان والروس حتى عام 1918 حيث تم إعلان الاستقلال. اعترفت الأخيرة بإستونيا عام 1920 وأُعلن قيام جمهورية برلمانية و تأميم أراضي النُبلاء في نفس العام. انضمت دول البلطيق الثلاث اللى عصبة الأمم المتحدة عام 1921. عاشت استونيا في الفترة 1921 إلى 1940 فترة سياسية غير مستقرة أهم أحداثها تشكيل حكومة فاشية برئاسة قسطنطين باتس (Päts) عام 1934. اتفاق هتلر-ستالين عام 1939 أعطى الضوء الأخضر للاتحاد السوفياتي باحتلال جمهوريات البلطيق و من ضمنها استونيا، الذي تم في عام 1940 أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية (1939-1945) بدون أي سابق انذار. بعد نشوب الحرب بين ألمانيا والاتحاد السوفيتي، قامت الأولى بإحتلال جمهوريات البلطيق عام 1941، إلى أن أعاد الجيش الأحمر إحتلالهم و إعادتهم تحت سيطرة الاتحاد السوفيتي.

بقي تاريخ البلاد جزء من التاريخ السوفيتي في السنوات المقبلة حتى الأعوام 1988 - 1990، عندما بدأ الاتحاد السوفيتي بالانهيار وتزايد الأصوات المطالبة باستقلال البلاد. وأعلنت إستونيا استقلالها عام 1990، واعترف مجلس السوفيت الأعلى في العام التالي بالجمهورية الجديدة. انضمت إستونيا إلى الأمم المتحدة عام 1992 وإلى الاتحاد الاوروبي عام 2004.

عصر الڤايكنگ

The Estonian coast was a trade hub located on a major waterway, making it both a target and a starting point for many raids. Coastal Estonians, particularly Oeselians from Saaremaa, adopted a Viking lifestyle.[38][39] Several Scandinavian sagas referred to major confrontations with Estonians, notably when 7th century "Estonian Vikings" defeated and killed Ingvar Harra, the King of Swedes.[40][41] The mid-8th century Salme ship burials have been proposed as the beginning of the European Viking Age.[42][43]

In ح. 1030, Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise of Kievan Rus attempted to subjugate the Chuds (as East Slavic sources called Estonians and related Finnic tribes) in southeast Estonia and captured Tartu. Chuds (Sosols) destroyed this foothold in 1061.[44][45][46][47] In 1187, Estonians, Curonians and Karelians sacked Sigtuna, a major Swedish city at the time.[48][37]

In the early centuries AD, Estonia's first administrative subdivisions emerged, primarily the parish (Estonian: kihelkond) and the county (Estonian: maakond). Counties usually included multiple parishes which local nobles referred to as kings (Estonian: kuningas) typically governed.[49] Ancient Estonia had a professional warrior caste[50] while international trade provided nobles wealth and prestige.[51] Parishes were commonly centred on hill forts, though occasionally a parish had multiple forts. By the 13th century, Estonia was divided into eight major counties – Harjumaa, Järvamaa, Läänemaa, Revala, Saaremaa, Sakala, Ugandi, and Virumaa – and several smaller, single-parish counties. Counties operated independently, forming only loose defensive alliances against foreign threats.[52][53]

Estonia had two regional cultures in this period. Northern and western coastal areas maintained close connections with Scandinavia, while the inland had stronger ties to the Balts and the principality of Pskov.[54] Viking Age Estonia participated actively in trade, including exports of iron, furs, and honey. They imported fine goods like silk, jewelry, glass, and Ulfberht swords. Evidence of ancient harbour sites has been found along the coast of Saaremaa.[55] This era's Estonian burial sites often contain both individual and collective graves, with artefacts like weapons and jewelry reflecting the shared material culture of Scandinavia and Northern Europe.[55][56]

Very little is known about the religious beliefs of medieval Estonians prior to Christianisation. A 1229 chronicle mentions Tharapita as the supreme deity of the islanders of Saaremaa (Ösel). Sacred groves, particularly of oak trees, factored prominently into pagan worship practices.[57][58] Albeit foreign traders and missionaries introduced Christian (both Western Catholic and Eastern Orthodox) practices already in the 10th–11th centuries, most people retained their indigenous beliefs.[59]

الحملات الصليبية والعصر الكاثوليكي

In 1199, Pope Innocent III declared a crusade to "defend the Christians of Livonia".[60] The crusading German Swordbrothers, who had previously subjugated Livonians, Latgalians, and Selonians, started campaigning against Estonians in 1208. The following years saw many raids and counter-raids. In 1217, the Estonians suffered a significant defeat in the battle where their most prominent leader Lembitu, an elder of Sakala, was killed. In 1219, the armies of King Valdemar II of Denmark defeated Estonians in the Battle of Lyndanisse (Tallinn), and conquered northern Estonia.[61][62] In the uprising of 1223, Estonians were able to push the German and Danish invaders out of the whole country, except Tallinn. The Catholic crusaders soon resumed their offensive, and in 1227, Saaremaa was the last Estonian maakond ("pagan county") to surrender, and convert to Christianity.[63][64]

In the 13th century, the newly Christian territory of present-day Estonia and Latvia was named Terra Mariana; later it became known simply as Livonia.[65] North Estonia became part of the Kingdom of Denmark. The rest was divided between Swordbrothers and the Holy Roman Empire's prince-bishops of Dorpat and Ösel–Wiek. In 1236, the Swordbrothers merged into the then larger Teutonic Order (becoming its regional branch, the "Livonian Order").[66] In the areas between southeast Estonia and the city of Pskov, then part of the Novgorod Republic, the indigenous Setos converted to Eastern Orthodoxy.[67]

Initially, Estonian nobles who accepted baptism could retain their power and influence by becoming vassals of the king of Denmark or the local Catholic prince-bishops of the Holy Roman Empire. The indigenous Estonian nobles intermarried with the newcomers, and several centuries later their descendants would become known as the Baltic Germans.[68] In 1343, a major anti-German uprising encompassed north Estonia and Saaremaa. The Teutonic Order suppressed the rebellion by 1345, and the next year bought the Estonian lands from the king of Denmark.[69][70] The German upper-class minority consolidated their power after the unsuccessful rebellion.[71] For the subsequent centuries Low German remained the language of the ruling elite in both Estonian cities and the countryside.[72]

Tallinn, the capital of Danish Estonia founded on the site of Lindanise, adopted the Lübeck law and received full town rights in 1248.[73] The Hanseatic League controlled trade on the Baltic Sea, and the four largest cities in Estonia became members: Tallinn, Tartu, Pärnu, and Viljandi.[74] Protected by stone walls and membership in the Hansa, prosperous cities like Tallinn and Tartu often defied other rulers of the medieval Livonian Confederation.[75][أ]

الإصلاح والحرب الليڤونية

In the 1520s, as new ideas of Reformation and Protestantism spread northwards, the then Master of the Livonian Order Wolter von Plettenberg sought to maintain stability while resisting religious change.[77] Despite this, the Protestant teachings of Martin Luther gained momentum in Tallinn by 1525, prompting the town council to embrace Lutheranism. Churches and monasteries in Tallinn and Tartu were damaged in iconoclastic riots. By the late 1520s, most towns had converted, though Catholicism persisted in some areas and rural regions were slower to follow.[78][79] The Reformation introduced vernacular church services, shifting from Low German to Estonian by the 1530s.[78][80] Early Estonian-language Protestant texts emerged, including Wanradt–Koell Catechism in 1535.[81] Ethnic Estonian townspeople, inspired by Protestant ideals, also sought greater rights during the Reformation.[82]

During the 16th century, the expansionist monarchies of Muscovy, Sweden, and Poland became a growing threat to the Old Livonia then weakened by disputes between cities, nobility, prince-bishops, and the Teutonic Order.[78][83] In 1558, Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia (Muscovy) invaded Livonia, starting the Livonian War. The Order was decisively defeated in 1560. The majority of Livonia accepted Polish–Lithuanian rule, while Tallinn and the nobles of northern Estonia swore loyalty to the king of Sweden, and the bishop of Ösel-Wiek sold his lands to Denmark. Tsar Ivan's forces were at first able to conquer the larger part of Livonia. Plague swept through the land, compounding the destruction.

Reports of the Russian atrocities spread over Europe. Many chroniclers of the era depicted Tsar Ivan as barbaric and tyrannical, emphasizing the suffering of local populations under Muscovite occupation. These accounts shaped the European perceptions of Tsar Ivan and his armies as brutal oppressors.[84] Muscovite armies twice laid a siege on Tallinn, yet failed to capture it.[85] In 1580, the Polish and Swedish armies went on the offensive; the war ended in 1583 with Ivan's defeat.[83][86]

As a result of the war, north Estonia became part of Sweden, south Estonia part of Poland, and Saaremaa remained part of Denmark.[87] During Polish rule in south Estonia, efforts were made to restore Catholicism, yet this was distinct from traditional Counter-Reformation, as Polish rulers fostered religious tolerance. Jesuit influence also flourished, and institutions were established, e.g Collegium Derpatense in Tartu, where Estonian-language catechisms were published to support local missions. Jesuits' presence in Tartu was cut short by Swedish conquest in the early 17th century.[88]

الحكم السويدي والروسي

Wars between Sweden and Poland-Lithuania continued until 1629, when the victorious Sweden acquired south Estonia and northern Latvia.[89] Sweden gained Saaremaa from Denmark in 1645.[90] The wars cut the population of Estonia from about 250–270,000 people in the mid-16th century to 115–120,000 in the 1630s.[91]

The Swedish era in Estonia was marked by both religious repression and significant reforms. Initially, it brought Protestant puritans who opposed traditional Estonian beliefs and practices, leading to witch trials and bans on folk music.[92] While large parts of rural population remained in serfdom, legal reforms under King Charles XI strengthened both serfs' and free tenant farmers' land usage and inheritance rights, resulting in this period's reputation as "The Good Old Swedish Time" in historical memory.[93] King Gustav II Adolph established gymnasiums in Tartu (which became the university in 1632) and Tallinn. Printers were established in both towns. The beginnings of the Estonian-language public education system appeared in the 1680s, largely owing to Bengt Forselius, who also introduced orthographical reforms to written Estonian.[94] The population of Estonia grew rapidly until about 20% of the population died in the Great Famine of 1695–97.[95]

By the Great Northern War, in which Tsar Peter I of Russia invaded Estonia in 1700, many Estonians were loyal to the Swedish crown. Up to 20,000 fought to defend Estonia against the invasion.[96] Reverential folk stories of the Swedish king Charles XII embody a sentiment that distinguished the Swedish era from the harsher Russian rule that followed. Despite the initial Swedish victory in the Battle of Narva, Russia conquered the whole of Estonia by the end of 1710.[97] The war again devastated the population of Estonia, with the 1712 population estimated at only 150,000–170,000.[98]

Under the 1710 terms of capitulation to Peter I, the country was incorporated into the Tsardom of Russia (after 1721 the Russian Empire), the tsar restored all political rights of the local German aristocracy, and recognised Lutheranism as the dominant faith.[99] Estonia was divided into two governorates: the Governorate of Estonia, which included Tallinn and north Estonia, and the Governorate of Livonia, which included south Estonia and parts of north Latvia.[100] The rights of local farmers reached their nadir, as serfdom completely dominated 18th century agricultural relations.[101]

Despite occasional Russian attempts to align Estonian governance with broader imperial standards, Baltic autonomy generally remained intact, as the tsarist regime sought to avoid conflicts with the local nobility. The Baltic "special order" remained largely in effect until the late 19th century, marking a distinctive period of localised governance within the Russian Empire. Although serfdom was abolished in Estonia already in 1816–1819, major reforms improving farmers' rights started in the mid-19th century.[102]

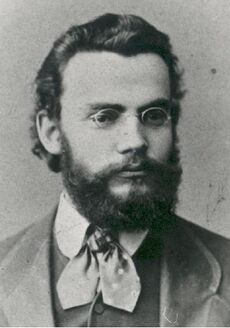

National Awakening

The Estonian national awakening began in the 1850s as several leading figures started promoting an Estonian national identity among the general populace. Widespread farm buyouts by Estonians and the resulting rapidly growing class of land-owning farmers provided the economic basis for the formation of this new "Estonian identity". In 1857 Johann Voldemar Jannsen started publishing the first Estonian language daily newspaper and began popularising the denomination of oneself as eestlane (Estonian).[103] Schoolmaster Carl Robert Jakobson and clergyman Jakob Hurt became leading figures in a national movement, encouraging Estonian farmers to take pride in their ethnic Estonian identity.[104] The first nationwide movements formed, such as a campaign to establish the Estonian language Alexander School, the founding of the Society of Estonian Literati and the Estonian Students' Society, and the first national song festival, held in 1869 in Tartu.[105][106][107] Linguistic reforms helped to develop the Estonian language.[108] The national epic Kalevipoeg was published in 1862, and 1870 saw the first performances of Estonian theatre.[109][110] In 1878 a major split happened in the national movement. The moderate wing led by Hurt focused on development of culture and Estonian education, while the radical wing led by Jakobson started demanding increased political and economical rights.[106]

At the end of the 19th century, Russification began, as the central government initiated various administrative and cultural measures to tie Baltic governorates more closely to the empire.[105] The Russian language replaced German and Estonian in most secondary schools and universities, and many social and cultural activities in local languages were suppressed.[110] In the late 1890s, there was a new surge of nationalism with the rise of prominent figures like Jaan Tõnisson and Konstantin Päts. In the early 20th century, Estonians started taking over control of local governments in towns from Germans.[111]

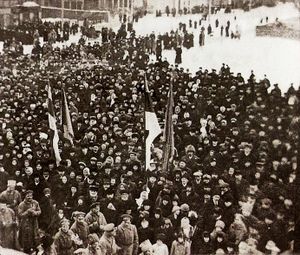

During the 1905 Revolution, the first legal Estonian political parties were founded. An Estonian national congress was convened and demanded the unification of Estonian areas into a single autonomous territory and an end to Russification. The unrest was accompanied by both peaceful political demonstrations and violent riots with looting in the commercial district of Tallinn and in a number of wealthy landowners' manors in the Estonian countryside. The Tsarist government responded with a brutal crackdown; some 500 people were executed and hundreds more jailed or deported to Siberia.[112][113]

Independence

In 1917, after the February Revolution, the governorate of Estonia was expanded by the Russian Provisional Government to include Estonian-speaking areas of Livonia and was granted autonomy, enabling the formation of the Estonian Provincial Assembly.[114] The Bolsheviks seized power in Estonia in November 1917, and the Provincial Assembly was disbanded. However, the Provincial Assembly established the Salvation Committee, and during the short interlude between Russian retreat and German arrival, the committee declared independence on 24 February 1918, and formed the Estonian Provisional Government. German occupation immediately followed, but after their defeat in World War I, the Germans were forced to hand over power back to the Provisional Government on 19 November 1918.[115][116]

On 28 November 1918 Soviet Russia invaded, starting the Estonian War of Independence.[117] The Red Army came within 30 km of Tallinn, but in January 1919, the Estonian Army, led by Johan Laidoner, went on a counter-offensive, ejecting Bolshevik forces from Estonia within a few months. Renewed Soviet attacks failed, and in spring, the Estonian army, in co-operation with White Russian forces, advanced into Russia and Latvia.[118][119] In June 1919, Estonia defeated the German Landeswehr which had attempted to dominate Latvia, restoring power to the government of Kārlis Ulmanis there. After the collapse of the White Russian forces, the Red Army launched a major offensive against Narva in late 1919, but failed to achieve a breakthrough. On 2 February 1920, the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed by Estonia and Soviet Russia, with the latter pledging to permanently give up all sovereign claims to Estonia.[118][120]

In April 1919, the Estonian Constituent Assembly was elected. The Constituent Assembly passed a sweeping land reform expropriating large estates, and adopted a new highly liberal constitution establishing Estonia as a parliamentary democracy.[121][122] In 1924, the Soviet Union organised a communist coup attempt, which quickly failed.[123] Estonia's cultural-autonomy law for ethnic minorities, adopted in 1925, is widely recognised as one of the most liberal in the world at that time.[124] The Great Depression put heavy pressure on Estonia's political system, and in 1933, the right-wing Vaps movement spearheaded a constitutional reform establishing a strong presidency.[125][126] On 12 March 1934 the acting head of state, Konstantin Päts, declared a state of emergency, under the pretext that the Vaps movement had been planning a coup. Päts, together with general Johan Laidoner and Kaarel Eenpalu, established an authoritarian régime during the "era of silence", when the parliament did not reconvene and the newly established Patriotic League became the only legal political movement.[127] A new constitution was adopted in a referendum, and elections were held in 1938. Both pro-government and opposition candidates were allowed to participate, but only as independents.[128] The Päts régime was relatively benign compared to other authoritarian régimes in interwar Europe, and the régime never used violence against political opponents.[129]

Estonia joined the League of Nations in 1921.[130] Attempts to establish a larger alliance together with Finland, Poland, and Latvia failed, with only a mutual-defence pact being signed with Latvia in 1923, and later was followed up with the Baltic Entente of 1934.[131][132] In the 1930s, Estonia also engaged in secret military co-operation with Finland.[133] Non-aggression pacts were signed with the Soviet Union in 1932, and with Germany in 1939.[130][134] In 1939, Estonia declared neutrality, but this proved futile in World War II.[135]

الحرب العالمية الثانية

A week before the outbreak of World War II, on 23 August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. In the pact's secret protocol Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland were divided between USSR and Germany into "spheres of influence", with Estonia assigned to the Soviet "sphere".[136] On 24 September 1939, the Soviet Union demanded that Estonia sign a treaty of "mutual assistance" which would allow the Soviet Union to establish military bases in the country. The Estonian government felt that it had no choice but to comply, and the Soviet–Estonian Mutual Assistance Treaty was signed on 28 September 1939.[137] On 14 June, the Soviet Union instituted a full naval and air blockade on Estonia. On the same day, the airliner Kaleva was shot down by the Soviet Air Force. On 16 June, the USSR presented an ultimatum demanding completely free passage of the Red Army into Estonia and the establishment of a pro-Soviet government. Feeling that resistance was hopeless, the Estonian government complied and, on the next day, the whole country was occupied.[138][139] On 6 August 1940, Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union as the Estonian SSR.[140]

The USSR established a repressive wartime regime in occupied Estonia. Many of the country's high-ranking civil and military officials, intelligentsia and industrialists were arrested. Soviet repressions culminated on 14 June 1941 with mass deportation of around 11,000 people to Russia.[141][142] When Operation Barbarossa (accompanied by Estonian guerrilla soldiers called "Forest Brothers"[143]) began against the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 in the form of the "Summer War" (الإستونية: [Suvesõda] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), around 34,000 young Estonian men were forcibly drafted into the Red Army, fewer than 30% of whom survived the war. Soviet destruction battalions initiated a scorched earth policy. Political prisoners who could not be evacuated were executed by the NKVD.[144][145] Many Estonians went into the forest, starting an anti-Soviet guerrilla campaign. In July, German Wehrmacht reached south Estonia. The USSR evacuated Tallinn in late August with massive losses, and capture of the Estonian islands was completed by German forces in October.[146]

Initially, many Estonians were hopeful that Germany would help to restore Estonia's independence, but this soon proved to be in vain. Only a puppet collaborationist administration was established, and occupied Estonia was merged into Reichskommissariat Ostland, with its economy being fully subjugated to German military needs.[147] About a thousand Estonian Jews who had not managed to leave were almost all quickly killed in 1941. Numerous forced labour camps were established where thousands of Estonians, foreign Jews, Romani, and Soviet prisoners of war perished.[148] German occupation authorities started recruiting men into small volunteer units but, as these efforts provided meagre results and military situation worsened, forced conscription was instituted in 1943, eventually leading to formation of the Estonian Waffen-SS division.[149] Thousands of Estonians who did not want to fight in the German military secretly escaped to Finland, where many volunteered to fight together with Finns against Soviets.[150]

The Red Army reached the Estonian borders again in early 1944, but its advance into Estonia was stopped in heavy fighting near Narva for six months by German forces, including numerous Estonian units.[151] In March, the Soviet Air Force carried out heavy bombing raids against Tallinn and other Estonian towns.[152] In July, the Soviets started a major offensive from the south, forcing the Germans to abandon mainland Estonia in September and the Estonian islands in November.[151] As German forces were retreating from Tallinn, the last pre-war prime minister Jüri Uluots appointed a government headed by Otto Tief in an unsuccessful attempt to restore Estonia's independence.[153] Tens of thousands of people, including most of the Estonian Swedes, fled westwards to avoid the new Soviet occupation.[154]

Overall, Estonia lost about 25% of its population through deaths, deportations and evacuations in World War II.[155] Estonia also suffered some irrevocable territorial losses, as the Soviet Union transferred border areas comprising about 5% of Estonian pre-war territory from the Estonian SSR to the Russian SFSR.[156]

Second Soviet occupation

Thousands of Estonians opposing the second Soviet occupation joined a guerrilla movement known as the "Forest Brothers". The armed resistance was heaviest in the first few years after the war, but Soviet authorities gradually wore it down through attrition, and resistance effectively ceased to exist in the mid-1950s.[157] The Soviets initiated a policy of collectivisation, but as farmers remained opposed to it a campaign of terror was unleashed. In March 1949 about 20,000 Estonians were deported to Siberia. Collectivization was fully completed soon afterwards.[141][158]

The Russian-dominated occupation authorities under the Soviet Union began Russification, with hundreds of thousands of ethnic Russians and other "Soviet people" being induced to settle in occupied Estonia, in a process which eventually threatened to turn indigenous Estonians into a minority in their own native land.[159] In 1945 Estonians formed 97% of the population, but by 1989 their share of the population had fallen to 62%.[160] Occupying authorities carried out campaigns of ethnic cleansing, mass deportation of indigenous populations, and mass colonization by Russian settlers which led to Estonia losing 3% of its native population.[161] By March 1949, 60,000 people were deported from Estonia and 50,000 from Latvia to the gulag system in Siberia, where death rates were 30%. The occupying regime established an Estonian Communist Party, where Russians were the majority in party membership.[162] Economically, heavy industry was strongly prioritised, but this did not improve the well-being of the local population, and caused massive environmental damage through pollution.[163] Living standards under the Soviet occupation kept falling further behind nearby independent Finland.[159] The country was heavily militarised, with closed military areas covering 2% of territory.[164] Islands and most of the coastal areas were turned into a restricted border zone which required a special permit for entry.[165] Estonia was quite closed until the second half of the 1960s, when gradually Estonians began to covertly watch Finnish television in the northern parts of the country, thus getting a better picture of the way of life behind the Iron Curtain.[166]

The majority of Western countries considered the annexation of Estonia by the Soviet Union illegal.[167] Legal continuity of the Estonian state was preserved through the government-in-exile and the Estonian diplomatic representatives which Western governments continued to recognise.[168][169]

Independence restored

The introduction of perestroika by the central government of the Soviet Union in 1987 made open political activity possible again in Estonia, which triggered an independence restoration process later known as Laulev revolutsioon ("Singing revolution").[170] The environmental Fosforiidisõda ("Phosphorite war") campaign became the first major protest movement against the central government.[171] In 1988, new political movements appeared, such as the Popular Front of Estonia, which came to represent the moderate wing in the independence movement, and the more radical Estonian National Independence Party, which was the first non-communist party in the Soviet Union and demanded full restoration of independence.[172] On 16 November 1988, after the first non-rigged multi-candidate elections in half a century, the parliament of Soviet-controlled Estonia issued the Sovereignty Declaration, asserting the primacy of Estonian laws. Over the next two years, many other administrative parts (or "republics") of the USSR followed the Estonian example, issuing similar declarations.[173][174] On 23 August 1989, about 2 million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians participated in a mass demonstration, forming the Baltic Way human chain across the three countries.[175] In February 1990, elections were held to form the Congress of Estonia.[176] In March 1991, a referendum was held where 78.4% of voters supported full independence. During the coup attempt in Moscow, Estonia declared restoration of independence on 20 August 1991.[177]

Soviet authorities recognised Estonian independence on 6 September 1991, and on 17 September Estonia was admitted into the United Nations.[178] The last units of the Russian army left Estonia in 1994.[179]

In 1992 radical economic reforms were launched for switching over to a market economy, including privatisation and currency reform.[180] Estonia has been a member of the WTO since 13 November 1999.[181]

Since regaining independence in 1991, Estonian foreign policy has been aligned with other Western democracies, and in 2004 Estonia joined both the European Union and NATO.[182] On 9 December 2010, Estonia became a member of OECD.[183] On 1 January 2011, Estonia joined the eurozone and adopted the euro, the single currency of EU.[184] Estonia was a member of the UN Security Council 2020–2021.[185]

الاحتلال الألماني

A week before the outbreak of World War II, the 23 August 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact secretly assigned Estonia to the Soviet Union's sphere of influence.[186] In September 1939, during the Soviet invasion of Poland, Joseph Stalin pressured the Estonian government into signing a "mutual assistance treaty", allowing the USSR to establish military bases in Estonia.[187] On 14 June 1940, the Soviet Union instituted a full naval and air blockade on Estonia, shooting down the airliner Kaleva. On 16 June, the USSR demanded free passage of the Red Army into Estonia and the establishment of a pro-Soviet government. Feeling that resistance was hopeless, the Estonian government complied and Soviet occupation began.[188][189] The Independent Signal Battalion was the only unit of the Estonian Army to offer armed resistance.[190][191] On 6 August 1940, Estonia was formally annexed by the Soviet Union as the Estonian SSR.[140]

The USSR established a repressive terror regime in occupied Estonia, targeting the country's elite for destruction. Hundreds of people were executed and, on 14 June 1941, ح. 11,000 Estonians were deported to Russia, where most would be killed.[141][192] When Germany launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union on 22 June, the Summer War began in Estonia. The Soviet authorities conscripted around 34,000 young Estonian men; fewer than 30% would survive the war. Soviet extermination battalions adopted a scorched-earth policy, massacring civilians in the process, and NKVD units executed political prisoners who could not be evacuated.[193][194] Thousands of Estonians joined anti-Soviet partisan groups known as the Forest Brothers.[195] By mid-July, the Forest Brothers' uprising succeeded in liberating south Estonia ahead of the advancing German army, allowing local institutions of the pre-war Republic of Estonia to resume operation.[196] The Soviet armed forces and officials evacuated Tallinn by sea in late August 1941, suffering massive losses in the process.[146]

A puppet Estonian Self-Administration was established, and occupied Estonia was merged into Reichskommissariat Ostland.[197] About a thousand Estonian Jews were killed in 1941 and numerous forced labour camps were established.[148] German occupation authorities started recruiting men into volunteer units and limited conscription was instituted in 1943, eventually leading to formation of the Estonian Waffen-SS division.[198] Thousands of Estonians escaped to Finland, where many volunteered to fight together with Finns against Soviets.[199]

The Soviet Army reached the Estonian borders again in early 1944, heightening fears of a new Soviet occupation. The Estonian Self-Administration, with the support of major pre-war political parties and acting president Jüri Uluots, declared a general conscription, drafting 38,000 men into the Waffen-SS.[200][201][202] With significant support from Estonian units, German forces managed to halt the Soviet advance for six months in fierce battles near Narva.[151] The Soviet Air Force launched extensive bombing raids on Tallinn and other Estonian cities, resulting in severe damage and loss of life.[203] From July to September, the Soviet forces launched several major offensives, compelling German troops to withdraw.[151] During the German retreat, Jüri Uluots appointed a government led by Otto Tief in a final effort to restore independence. The government controlled Tallinn and parts of western Estonia, but failed to stop the Soviet offensive, which captured Tallinn on 22 September, followed by the rest of mainland Estonia. In November and December, German troops retreated from the Estonian islands, leaving the entire country under Soviet occupation.[204]

In 1944, tens of thousands of Estonians fled westwards from the Soviets.[205] Estonia lost around one fourth of its population through war-related deaths, deportations and evacuations.[206]

إستونيا السوڤيتية

Following renewed occupation, thousands of Estonians once again joined the Forest Brothers to resist Soviet rule. This armed resistance was particularly intense in the immediate post-war years, but by the 1960s, Soviet forces had conquered it through attrition.[207] The Soviet regime also intensified its policy of collectivisation, forcing farmers to abandon private agriculture and join state-run collectives. When locals resisted, authorities launched a campaign of terror, culminating in the March 1949 mass deportation of around 20,000 Estonians to the Siberian gulag.[208] Full collectivisation followed, marking a new phase of Soviet control.[141]

Simultaneously, the Soviet Union initiated Russification policies to reshape Estonia's demographics and dilute its cultural identity. Large numbers of Russians and other Soviet people were settled in Estonia.[159] Between 1945 and 1989, the proportion of ethnic Estonians in the country dropped from 97% to 62%.[209] Occupying authorities carried out campaigns of ethnic cleansing, mass deportation of Estonians, and mass Russian settlement.[210] Estonians faced additional hardships, as thousands were forcibly conscripted into Soviet military conflicts, including the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia and Soviet–Afghan War of 1979–1989.

The Soviet regime seized all industry and almost all agricultural land, neglecting most of the resulting damage to the environment and quality of life of the local people.[211][212] The military presence was pervasive, with closed military zones occupying around one-fifth of the Estonian land and the entire surrounding sea. Access to coastal areas required permits, rendering the Estonian people physically isolated from the world outside USSR.[213][214] Although Estonia had one of the highest standards of living compared to other parts of USSR, as a result of the Soviet occupation it fell far behind its neighbour Finland in economic development and quality of life.[215][159]

Soviet security forces enjoyed vast powers to suppress dissent, yet underground resistance endured. Despite heavy censorship, many Estonians covertly listened to Voice of America broadcasts and watched Finnish television, which offered a glimpse into life beyond the Iron Curtain.[216][217] In the late 1970s, Moscow's ideological pressure intensified with new Russian immigration. Estonian dissidents grew increasingly vocal, with notable protests such as the Baltic Appeal to the United Nations in 1979, and the Letter of 40 intellectuals in 1980.[218]

Most Western nations refused to recognise the Soviet annexation of Estonia, maintaining its illegality under international law.[219] Legal continuity of the Estonian state was preserved through the government-in-exile and the Estonian diplomatic representatives which Western governments continued to recognise.[220][221] This stance drew support from the Stimson Doctrine, which denied recognition of territorial changes enacted through force. American maps carried disclaimers explaining their representation of Estonia. In 1980, Tallinn hosted the sailing events for the Moscow Olympics, triggering international boycotts in protest of Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the continuing occupation of the Baltic countries. The Estonian exile community and Western nations condemned the events held on occupied soil.[222]

استعادة الاستقلال

The introduction of perestroika by the Soviet government in 1987 enabled political activism in Estonia, sparking the Singing Revolution, a peaceful movement towards independence.[223] One of the first major acts of resistance was the Phosphorite War, an environmental protest against Soviet plans to establish large phosphate mines in Virumaa.[224] On 23 August 1987, the Hirvepark meeting in Tallinn called for the public disclosure of the secret protocols of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that had led to Estonia's occupation. Although demands for independence were not yet made, organisers aimed to reinforce the continuity of the Estonian state as the foundation for a restoration based on legal principles.[225][226]

In 1988, new political movements emerged, including the Popular Front of Estonia, a moderate faction within the independence movement, and the Estonian National Independence Party, which became the first non-communist political party registered in the Soviet Union.[227] The parliament of Soviet-controlled Estonia asserted the primacy of Estonian laws with the Sovereignty Declaration on 16 November 1988, inspiring similar declarations across other Soviet republics.[228][229] On 23 August 1989, two million people formed the Baltic Way, a human chain spanning Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, to demonstrate unity in pursuit of independence.[230] In 1989, the Estonian Citizens' Committees began registering citizens according to jus sanguinis (i.e. people who were citizens of Estonia in 1940, and their descendants). This led to the February 1990 election of the Congress of Estonia, a special parliament for the restoration of nation's independence via legal continuity of its citizenry. In March 1991, a general referendum (where all citizens, resident non-citizens, and Soviet military personnel had a vote) 78.4% of voters supported full independence. During the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt in Moscow, Estonia declared the restoration of independence on 20 August 1991. The central government of the Soviet Union recognised the independence of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania on 6 September 1991, and on 17 September the three countries became members of the United Nations. The last military units of the former Soviet, now Russian, armed forces left Estonia in 1994.[231]

In 1992, a new Constitution of Estonia was approved by referendum, a new national currency (Estonian kroon) was introduced, the 1992 Estonian parliamentary election and presidential elections were held, where Lennart Meri was elected president and Mart Laar became prime minister. Under their leadership, Estonia initiated rapid and radical reforms, including privatisation and a currency overhaul, which accelerated the transition to a market economy.[211]

At the turn of the century Estonia launched the Tiigrihüpe programme, aiming to become an information society, and completed negotiations for membership in the European Union and NATO. Corporate income tax was abolished, and the national ID card was introduced.

Estonia joined the OECD in 2010.[232]

In April 2007, the Estonian authorities successfully stopped a multi-day pro-Russian riot in Tallinn and repelled a simultaneous wave of Russian cyberattacks targeting Estonian institutions. The 2007 incident further strained the relations with Russia, exacerbated by later Russian military attacks in Georgia and Ukraine. Estonia aligned with the EU in imposing against Russia the international sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War.[233]

Due to the 2008 financial crisis, Estonia's economic growth stalled in 2008, prompting strict government budget cuts to meet the criteria for adopting the euro. Estonia joined the Eurozone in 2011.[234]

الجغرافيا

تقع استونيا بين خطوط العرض 57.3 و 59.5 و خطوط الطول 21.5 و 28.1 على الساحل الشرقي لبحر البلطيق، في شمال شرق أوروبا. معدل علو الارتفاعات يبلغ 50 متر. أعلى جبل هو سور مونامغي (Suur Munamägi) و يبلغ 318 متر. الغابات تُشكل 47% من مساحة البلاد، اللتي تُعد بجانب الحجر الكلسي أهم موارد البلاد. تحتضن استونيا أكثر من 1400 بحيرة، معظمها صغيرة الحجم و أكبرها بحيرة هي بايبسي (Peipsi) بمساحة قدرها 3555 كم مربع. طول ساحل البلاد يزاهي ال 3794 كم (مع الجزر). يبلغ عدد الجزر الاستونية حوالي 1500 جزيرة.

Osmussaar is one of many islands in the territorial waters of Estonia.

Duckboards along a hiking trail in Viru bog in Lahemaa National Park. The longest hiking trail is 627 km (390 mi) long.[236]

Climate

Estonia is situated in the temperate climate zone, and in the transition zone between maritime and continental climate, characterized by warm summers and fairly mild winters. Primary local differences are caused by the Baltic Sea, which warms the coastal areas in winter, and cools them in the spring.[237][238] Average temperatures range from 17.8 °C (64.0 °F) in July, the warmest month, to −3.8 °C (25.2 °F) in February, the coldest month, with the annual average being 6.4 °C (43.5 °F).[239] The highest recorded temperature is 35.6 °C (96.1 °F) from 1992, and the lowest is −43.5 °C (−46.3 °F) from 1940.[240] The annual average precipitation is 662 ميليمتر (26.1 in),[241] with the daily record being 148 ميليمتر (5.8 in).[242] Snow cover varies significantly on different years.[238] Prevailing winds are westerly, southwesterly, and southerly, with average wind speed being 3–5 m/s inland and 5–7 m/s on coast.[238] The average monthly sunshine duration ranges from 290 hours in August, to 21 hours in December.[243]

Biodiversity

Due to varied climatic and soil conditions, and plethora of sea and internal waters, Estonia is one of the most biodiverse regions among the similar sized territories at the same latitude.[238] Many species extinct in most other European countries can be still found in Estonia.[244]

Recorded species include 64 mammals, 11 amphibians, and 5 reptiles.[237] Large mammals present in Estonia include the grey wolf, lynx, brown bear, red fox, badger, wild boar, moose, roe deer, beaver, otter, grey seal, and ringed seal. The critically endangered European mink has been successfully reintroduced to the island of Hiiumaa, and the rare Siberian flying squirrel is present in east Estonia.[244] The red deer, once extirpated, has also been successfully reintroduced.[245] In the beginning of the 21st century, an isolated population of European jackals was confirmed in Western Estonia, much further north than their earlier known range. The number of jackals has grown quickly in coastal areas of Estonia and can be found in Matsalu National Park.[246][247] Introduced mammals include sika deer, fallow deer, raccoon dog, muskrat, and American mink.[237]

Over 300 bird species have been found in Estonia, including the white-tailed eagle, lesser spotted eagle, golden eagle, western capercaillie, black and white stork, numerous species of owls, waders, geese and many others.[248] The barn swallow is the national bird of Estonia.[249]

Phytogeographically, Estonia is shared between the Central European and Eastern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Estonia belongs to the ecoregion of Sarmatic mixed forests.[250] Estonia has a rich composition of floristic groups, with estimated 6000 (3461 identified) fungi, 3000 (2500 identified) algae and cyanobacteria, 850 (786 identified) lichens, and 600 (507 identified) bryophytes. Forests cover approximately half of the country. 87 native and over 500 introduced tree and bush species have been identified, with most prevalent tree species being pine (41%), birch (28%), and spruce (23%).[237] Since 1969, the cornflower (Centaurea cyanus) has been the national flower of Estonia.[251]

Protected areas cover 19.4% of Estonian land and 23% of its total area together with territorial sea. Overall there are 3,883 protected natural objects, including 6 national parks, 231 nature conservation areas, and 154 landscape reserves.[252]

السياسة

Estonia is a unitary parliamentary republic. The unicameral parliament Riigikogu serves as the legislative and the government as the executive.[253]

Estonian parliament Riigikogu is elected by citizens over 18 years of age for a four-year term by proportional representation, and has 101 members. Riigikogu's responsibilities include approval and preservation of the national government, passing legal acts, passing the state budget, and conducting parliamentary supervision. On proposal of the president Riigikogu appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the chairman of the board of the Bank of Estonia, the Auditor General, the Legal Chancellor, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces.[254][255]

The Government of Estonia is formed by the Prime Minister of Estonia at recommendation of the President, and approved by the Riigikogu. The government, headed by the Prime Minister, carries out domestic and foreign policy. Ministers head ministries and represent its interests in the government. Sometimes ministers with no associated ministry are appointed, known as ministers without portfolio.[256] Estonia has been ruled by coalition governments because no party has been able to obtain an absolute majority in the parliament.[253]

The head of the state is the President who has a primarily representative and ceremonial role. There are no referendums on the election of the president, but the president is elected by the Riigikogu, or by a special electoral college.[257] The President proclaims the laws passed in the Riigikogu, and has right to refuse proclamation and return law in question for a new debate and decision. If Riigikogu passes the law unamended, then the President has right to propose to the Supreme Court to declare the law unconstitutional. The President also represents the country in international relations.[253][258]

The Constitution of Estonia also provides possibility for direct democracy through referendum, although since adoption of the constitution in 1992 the only referendum has been the referendum on European Union membership in 2003.[259]

Estonia has pursued the development of the e-government, with 99 percent of the public services being available on the web 24 hours a day.[260] In 2005 Estonia became the first country in the world to introduce nationwide binding Internet voting in local elections of 2005.[261] In 2023 parliamentary elections 51% of the total votes were cast over the internet, becoming the first time when more than half of votes were cast online.[262]

In the most recent parliamentary elections of 2023, six parties gained seats at Riigikogu. The head of the Reform Party, Kaja Kallas, formed the government together with Estonia 200 and Social Democratic Party, while Conservative People's Party, Centre Party and Isamaa became the opposition.[263][264]

القانون

The Constitution of Estonia is the fundamental law, establishing the constitutional order based on five principles: human dignity, democracy, rule of law, social state, and the Estonian identity.[265] Estonia has a civil law legal system based on the Germanic legal model.[266] The court system has a three-level structure. The first instance are county courts which handle all criminal and civil cases, and administrative courts which hear complaints about government and local officials, and other public disputes. The second instance are district courts which handle appeals about the first instance decisions.[267] The Supreme Court is the court of cassation, conducts constitutional review, and has 19 members.[268] The judiciary is independent, judges are appointed for life, and can be removed from office only when convicted of a crime.[269] The justice system has been rated among the most efficient in the European Union by the EU Justice Scoreboard.[270] As of June 2023, gay registered partners and married couples have the right to adopt. Gay couples will gain the right to marriage in Estonia in 2024. Estonia is the first of the former Soviet republics to legalize same-sex marriage.[271][272]

العلاقات الخارجية

Estonia was a member of the League of Nations from 22 September 1921, and became a member of the United Nations on 17 September 1991.[273][274] Since restoration of independence Estonia has pursued close relations with the Western countries, and has been member of NATO and the European Union since 2004.[274] In 2007, Estonia joined the Schengen Area, and in 2011 the Eurozone.[274] The European Union Agency for large-scale IT systems is based in Tallinn, and started operations at the end of 2012.[275] Estonia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2017.[276]

Since the early 1990s, Estonia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic states co-operation with Latvia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic co-operation with the Nordic countries. Estonia is a member of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly, the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers and the Council of the Baltic Sea States.[277] Estonia has built close relationship with the Nordic countries, especially Finland and Sweden, and is a member of Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB-8).[274][278] Joint Nordic-Baltic projects include the education programme Nordplus[279] and mobility programmes for business and industry[280] and for public administration.[281] The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Tallinn with a subsidiaries in Tartu and Narva.[282][283] The Baltic states are members of Nordic Investment Bank, European Union's Nordic Battle Group, and in 2011 were invited to co-operate with Nordic Defence Cooperation in selected activities.[284][285][286][287]

The beginning of the attempt to redefine Estonia as "Nordic" was seen in December 1999, when then Estonian foreign minister (and President of Estonia from 2006 until 2016) Toomas Hendrik Ilves delivered a speech entitled "Estonia as a Nordic Country" to the Swedish Institute for International Affairs,[288] with the potential political calculation behind it being the wish to distinguish Estonia from its more slowly progressing southern neighbours, which could have postponed early participation in European Union enlargement.[289] Andres Kasekamp argued in 2005, that relevance of identity discussions in Baltic states decreased with their entrance into EU and NATO together, but predicted, that in the future, attractiveness of Nordic identity in Baltic states will grow and eventually, five Nordic states plus three Baltic states will become a single unit.[289]

Other Estonian international organisation memberships include OECD, OSCE, WTO, IMF, the Council of the Baltic Sea States,[274][290][291] and on 7 June 2019, was elected a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for a two-year term that began on 1 January 2020.[292]

Since the Soviet era, the relations with Russia remain generally cold, even though practical co-operation has taken place in between.[293] Since 24 February 2022, the relations with Russia have further deteriorated when Russia made its invasion on Ukraine. Estonia has very actively supported Ukraine during the war, providing highest support relative to its gross domestic product.[294][295]

Military

The Estonian Defence Forces consist of land forces, navy, and air force. The current national military service is compulsory for healthy men between ages of 18 and 28, with conscripts serving 8- or 11-month tours of duty, depending on their education and position provided by the Defence Forces.[296] The peacetime size of the Estonian Defence Forces is about 6,000 persons, with half of those being conscripts. The planned wartime size of the Defence Forces is 60,000 personnel, including 21,000 personnel in high readiness reserve.[297] Since 2015 the Estonian defence budget has been over 2% of GDP, fulfilling its NATO defence spending obligation.[298]

The Estonian Defence League is a voluntary national defence organisation under management of Ministry of Defence. It is organised based on military principles, has its own military equipment, and provides various different military training for its members, including in guerilla tactics. The Defence League has 17,000 members, with additional 11,000 volunteers in its affiliated organisations.[299][300]

Estonia co-operates with Latvia and Lithuania in several trilateral Baltic defence co-operation initiatives. As part of Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET) the three countries manage the Baltic airspace control center, Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) has participated in the NATO Response Force, and a joint military educational institution Baltic Defence College is located in Tartu.[301]

Estonia joined NATO in 2004. NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence was established in Tallinn in 2008.[302] In response to Russian war in Ukraine, since 2017 a NATO Enhanced Forward Presence battalion battle group has been based in Tapa Army Base.[303] Also part of NATO Baltic Air Policing deployment has been based in Ämari Air Base since 2014.[304] In European Union Estonia participates in Nordic Battlegroup and Permanent Structured Cooperation.[305][306]

Since 1995 Estonia has participated in numerous international security and peacekeeping missions, including: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Kosovo, and Mali.[307] The peak strength of Estonian deployment in Afghanistan was 289 soldiers in 2009.[308] 11 Estonian soldiers have been killed in missions of Afghanistan and Iraq.[309]

التقسيمات الإدارية

Estonia is a unitary country with a single-tier local government system. Local affairs are managed autonomously by local governments. Since administrative reform in 2017, there are in total 79 local governments, including 15 towns and 64 rural municipalities. All municipalities have equal legal status and form part of a maakond (county), which is an administrative subunit of the state.[310] Representative body of local authorities is municipal council, elected at general direct elections for a four-year term. The council appoints local government. For towns, the head of the local goverment is linnapea (mayor) and vallavanem for parishes. For additional decentralization the local authorities may form municipal districts with limited authority, currently those have been formed in Tallinn and Hiiumaa.[311]

Separately from administrative units, there are also settlement units: village, small borough, borough, and town. Generally, villages have less than 300, small boroughs have between 300 and 1000, boroughs and towns have over 1000 inhabitants.[311]

السياسة

إستونيا هي دولة دستورية ديمقراطية. رئيس الجمهورية هو أعلى منصب سياسي يُنتخب من برلمان الدولة (Riigikogu)، ذو المجلس الأحادي، كل خمس سنوات. الحكومة ، اللتي تتشكل من 14 وزير، هي الذراع التنفيذي للرئيس. الحكومة تُعين من الرئيس بعد موافقة البرلمان عليها. البرلمان يتكون من 101 نائب، اللذين ينتخبوا كل أربع سنوات بشكل مباشر من الشعب. المحكمة القضائية العليا هي المحكمة الوطنية (Riigikohus)، اللتي تتكون بدورها من 17 قاضي يرأسهم رئيس القضاة اللذي يعين من البرلمان.

Estonia is a unitary parliamentary republic where the unicameral parliament, Riigikogu, serves as the legislature and the government acts as the executive branch.[253] The Riigikogu comprises 101 members elected for four-year terms by proportional representation, with voting rights granted to citizens over 18 years of age. The parliament approves the national government, passes legal acts and the state budget, and exercises parliamentary oversight. Additionally, upon the president's recommendation, the Parliament appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the chair of the Bank of Estonia, the Auditor General, the Chancellor of Justice, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces.[312][313]

The Government of Estonia, led by the Prime Minister, is nominated by the President, subject to parliamentary approval. Estonia's political system has been marked by coalition governments, as no single party has managed to secure an absolute majority in parliament.[253] The President, Estonia's head of state, plays a mostly ceremonial role, representing the nation internationally and holding the power to proclaim or veto laws passed by the Parliament. Should a law be passed unamended after presidential veto, the President may petition the Supreme Court to review its constitutionality.[253][314] There is no direct election of the president, who is elected by the Riigikogu, or by a special electoral college.[315]

The Constitution of Estonia allows referendums. After the adoption of the current constitution by a referendum in 1992, only one more referendum has been held: the 2003 Estonian European Union membership referendum.[316] Estonia has pioneered in e-government, offering nearly all public services online[317] and becoming the first country globally to enable nationwide binding Internet voting in 2005 local elections.[318] During the 2023 parliamentary elections, over half of the votes were cast online.[319] Six parties secured seats in the Riigikogu in the 2023 elections, with Kaja Kallas of the Reform Party forming a coalition government with Estonia 200 and the Social Democratic Party, while the Conservative People's Party, Centre Party and Isamaa became the opposition.[320][321] In 2024, after Kallas' resignation, Kristen Michal became the prime minister.[322]

Estonia is a unitary country with a single-tier local government system. Local affairs are managed autonomously by local governments. Since administrative reform in 2017, there are in total 79 local governments, including 15 towns and 64 rural municipalities. All municipalities have equal legal status and form part of a maakond (county), which is an administrative subunit of the state.[323] Representative body of local authorities is municipal council, elected at general direct elections for a four-year term. Each municipal council appoints the mayor and the local government. The local authorities may form municipal districts with limited authority — such municipal districts have been formed, e.g in Tallinn and Hiiumaa.

Local governments in Estonia are not intended as extensions of the central government. Instead, they serve to directly address the needs of each local community. Issues such as construction projects, road maintenance, waste management, and quality-of-life initiatives are handled primarily by local governments. The state provides financial and legislative support, ensuring that local governments have adequate funding for these initiatives.[324]

The Constitution of Estonia is the fundamental law. It is based on five main principles: human dignity, democracy, rule of law, social state, and the Estonian identity.[325] Estonia has a civil law legal system based on the Germanic legal model.[326] The court system has a three-level structure. The first instance are county courts which handle all criminal and civil cases, and administrative courts which hear complaints about government and local officials, and other public disputes. The second instance are district courts which handle appeals about the first instance decisions.[327] The Supreme Court is the court of cassation, conducts constitutional review, and has 19 members.[328] The judiciary is independent, judges are appointed for life, and can be removed from office only when convicted of a crime.[329] The justice system has been rated among the most efficient in the EU by the EU Justice Scoreboard.[330]

The Estonian legal system is built upon stable democratic institutions, with an independent judiciary as a fundamental pillar of the rule of law. However, concerns remain regarding the judiciary's structural independence, particularly due to the Ministry of Justice's significant role in managing lower courts and overseeing their administration. This connection has raised questions about potential indirect influence on judicial decision-making, as the Ministry's oversight and control of court finances limit the financial autonomy of the courts, making them more susceptible to political pressures.

Estonia legalised civil unions for same-sex couples with a law approved by the parliament in 2014.[331] Same-sex couples gained the right to sign cohabitation agreements in 2016. In 2023, gay registered partners and married couples gained limited right to adopt. Gay couples gained the right to marriage in Estonia in 2024.[332]

Law enforcement in Estonia is primarily managed by agencies under the Ministry of the Interior. The main agency, the Police and Border Guard Board, oversees law enforcement and internal security, responsible for a range of duties from public order to immigration control. Estonia also has a strong private security sector, which provides additional security services to individuals and businesses but holds no legal authority to arrest or detain suspects. To address national security, the Estonian Internal Security Service serves as the country's principal counterintelligence and counterterrorism agency, while the Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service handles external threats, gathering intelligence abroad to protect Estonia's national interests.[333] Emergency services in Estonia include comprehensive emergency medical services and the Estonian Rescue Board, which is responsible for search and rescue operations across the country.

العلاقات الخارجية

As a member of the former League of Nations from 1921, and of the United Nations since 1991,[334][274] Estonia quickly integrated into European and transatlantic frameworks, joining NATO and the EU in 2004.[274] In 2007, Estonia joined the Schengen Area, and in 2011 the Eurozone.[274] Tallinn hosts the eu-LISA systems, operational since 2012,[335] and Estonia held the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2017.[336] Estonia is also a member of the OECD, OSCE, WTO, and IMF.[274][337][338]

Estonia's has engaged in ever closer regional cooperation with Latvia and Lithuania, and participates in several regional councils, such as the Baltic Assembly, the Baltic Council of Ministers, the Council of the Baltic Sea States,[339] and the Three Seas Initiative.[340]

Since the end of the Soviet occupation in 1991, the Estonia–Russia relations have remained strained.[341] Since 24 February 2022, the relations with Russia have further deteriorated due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Estonia has strongly supported Ukraine during the war, providing highest support relative to its gross domestic product.[342][343]

Estonia has built close relationship with the Nordic countries and is a member of Nordic-Baltic Eight.[274][278] Joint Nordic-Baltic projects include the education programme Nordplus[344] and mobility programmes for business and industry[345] and for public administration.[346] The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Tallinn with a subsidiaries in Tartu and Narva.[347][348] The Baltic states are members of Nordic Investment Bank, the EU's Nordic Battle Group, and in 2011 were invited to co-operate with Nordic Defence Cooperation in selected activities.[349][350][351][352]

العسكرية

The Estonian Defence Forces consist of land forces, navy, and air force. The current national military service is compulsory for healthy men between ages of 18 and 28, with conscripts serving 8- or 11-month tours of duty, depending on their education and position provided by the Defence Forces.[353] The peacetime size of the Estonian Defence Forces is about 6,000 persons, with half of those being conscripts. The planned wartime size of the Defence Forces is 60,000 personnel, including 21,000 personnel in high readiness reserve.[354] Since 2015, the Estonian defence budget has been over 2% of GDP, fulfilling its NATO defence spending obligation.[355]

The Estonian Defence League is a voluntary national defence organisation under management of Ministry of Defence. It is organised based on military principles, has its own military equipment, and provides various different military training for its members, including in guerilla tactics. The Defence League has 17,000 members, with additional 11,000 volunteers in its affiliated organisations.[356][357]

Estonia co-operates with Latvia and Lithuania in several trilateral defence co-operation initiatives. As part of Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET) the three countries manage the common airspace control centre, Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) has participated in the NATO Response Force, and a joint military educational institution Baltic Defence College is located in Tartu.[358] Estonia joined NATO on 29 March 2004.[359] NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence was established in Tallinn in 2008.[360] In response to Russian war in Ukraine, since 2017 a NATO Enhanced Forward Presence battalion battle group has been based in Tapa Army Base.[361] Also part of NATO, the Baltic Air Policing deployment has been based in Ämari Air Base since 2014.[362] In the EU, Estonia participates in Nordic Battlegroup and Permanent Structured Cooperation.[363][364]

According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Estonia is the 24th most peaceful country in the world.[365] Since 1995, Estonia has participated in numerous international security and peacekeeping missions, including: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Kosovo, and Mali.[366] The peak strength of Estonian deployment in Afghanistan was 289 soldiers in 2009.[367] Eleven Estonian soldiers have been killed in missions of Afghanistan and Iraq.[368] In addition, up to a hundred Estonian volunteers have joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine during the Russian invasion of Ukraine,[369] three of whom have been killed.[370]

الاقتصاد

بعد إنتهاء الحقبة الشيوعية بالبلاد حولت إستونيا نظامها الاقتصادي تدريجياً، آخذة اقتصاديات الدول الاسكندنافية كمثل أعلى لها، اللتي تمتاز بقلة البيروقراطية ، شفافية أنظمة الدولة و اتصالات حديثة. الاقتصاد الإستوني أصبح ينمو بسرعة و ثقة أكثر بعد دخول البلاد بالاتحاد الاوروبي عام 2004. أهم الصناعات هي الغذائية و الكهربائية. أيضاً صيد الأسماك و صناعة الأثاث لهم دور مهم بدفع عجلة النمو و زيادة الصادرات. أهم الشركاء التجاريين هم الدول الاسكندنافية و خاصة فنلندا.

إستونيا كانت إحدى الدول الرائدة لإدخال نظام ضريبي فريد من نوعه (عام 1994) يقضي باستقتطاع 26% من دخل الفرد كضريبة دخل بغض النظر عن مهنته، لاحقاً تم خفضها إلى 24%.

الطرق البرية و الملاحة البحرية هي أهم سبل المواصلات في البلاد. تُستعمل السكك الحديدية بشكل رئيسي لنقل البضائع. الموانئ البحرية الكبيرة تتواجد في العاصمة تالين و بارنو. يخترق الطريق السريع شارع البلطيق (Via Baltica) من جنوب البلاد إلى شمالها.

Estonia is a developed country with an advanced, high-income economy that was among the fastest-growing in the EU since its entry in 2004.[371] With a GDP (PPP) per capita of $46,385 in 2023, ranked 40th globally by the IMF,[372] Estonia ranks highly in international rankings for education,[373][374] press freedom,[375] digitalisation of public services,[376][377] the prevalence of technology companies,[378] and maintains very high rankings in the Human Development Index.[379] Free education[380] and the longest paid maternity leave in the OECD[381] are also distinctive characteristics of modern Estonian social fabric.

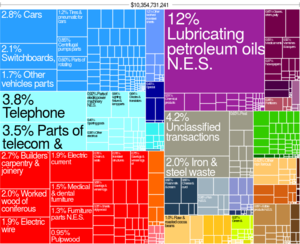

Telecommunications, energy, textiles, chemical products, banking, services, food and fishery, timber, shipbuilding, electronics, and transportation are key sectors of the economy.[382] Historically, the locally mined oil shale was the main source of energy, contributing over 85% of energy production in early 2010s,[383] with renewable sources like wood, peat, and biomass accounting for the remaining part of primary energy production. The share of wind energy, comprising only 6% of energy consumption in 2009,[384] has been rapidly growing in recent years.

The 2008 financial crisis impacted Estonia with an initial contraction of GDP, which led to governmental budget adjustments to stabilise the economy. By 2010, the economy began to recover driven by exports, and annual industrial output increased by over 20%.[385] Real GDP growth in 2011 reached 8%, and in 2012, Estonia was the only eurozone country with a budget surplus, with national debt at 6%, among the lowest in EU. Despite economic disparities between regions – over half of the GDP is generated in the capital city Tallinn – the country has continued to perform well, including a notable first-place ranking in the Environmental Performance Index in 2024.[386]

Public policy

Estonia's economy continues to benefit from a transparent government and policies that sustain a high level of economic freedom, ranking 6th globally and 2nd in Europe.[387][388] The rule of law remains strongly buttressed and enforced by an independent and efficient judicial system. A simplified tax system with flat rates and low indirect taxation, openness to foreign investment, and a liberal trade regime have supported the resilient and well-functioning economy.[389] اعتبارا من مايو 2018[تحديث], the Ease of Doing Business Index by the World Bank Group places the country 16th in the world.[390] The strong focus on the IT sector through its e-Estonia programme has led to much faster, simpler and efficient public services where for example filing a tax return takes less than five minutes and 98% of banking transactions are conducted through the internet.[391][392] Estonia has the 13th lowest business bribery risk in the world, according to TRACE Matrix.[393]

After restoring independence, in the 1990s, Estonia eagerly pursued economic reform and reintegration with other Western democracies.[394] In 1994, applying the economic theories of Milton Friedman, Estonia became one of the first countries to adopt a flat tax, with a uniform rate of 26% regardless of personal income. This rate has since been reduced several times, e.g., to 24% in 2005, 23% in 2006, and to 21% in 2008.[395] The Government of Estonia adopted the euro as the country's currency on 1 January 2011, later than planned due to then continued high inflation.[396]

النقل

The primary modes of transportation in Estonia include road, rail, maritime, and air transport, each contributing significantly to the economy and accessibility of the region. Port of Tallinn is one of the largest maritime enterprises in the Baltic Sea, catering to both cargo and passenger traffic. Among the facilities is the ice-free port of Muuga, located near Tallinn, which boasts modern transhipment capabilities, a high-capacity grain elevator, chill and frozen storage, and enhanced oil tanker offloading facilities.[397] Estonian shipping company Tallink operates a fleet of Baltic Sea cruiseferries and ropax ships. Tallink is the largest passenger and cargo shipping operator in the Baltic Sea, with routes connecting Estonia to Finland and Sweden. The ferry lines to Estonian islands are operated by TS Laevad and Kihnu Veeteed.[398]