ڤنزويلا

جمهورية ڤنـِزويلا البوليـڤـارية[a]

| |

|---|---|

| |

| العاصمة | كراكاس |

| أكبر مدينة | العاصمة |

| اللغات الإقليمية المعترف بها | |

| اللغة الرسمية | الإسپانية |

| الجماعات العرقية (2011[1]) |

|

| صفة المواطن | ڤنزويلي |

| الحكومة | جمهورية دستورية اتحادية رئاسية |

• الرئيس | نيكولاس مادورو (الاشتراكي المتحد) |

| Delcy Rodríguez | |

| Diosdado Cabello (الاشتراكي المتحد) | |

| التشريع | الجمعية الوطنية |

| المساحة | |

• الإجمالية | 916،445 km2 (353،841 sq mi) (33) |

• الماء (%) | 0.32[d] |

| التعداد | |

• تقدير 2023 | |

• إحصاء | 33,221,865[3] |

• الكثافة | 33.74/km2 (87.4/sq mi) (144th) |

| ن.م.إ. (ق.ش.م.) | تقدير 2023 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $211.926 billion[4] (81st) |

• للفرد | ▲ $7,985[4] (159th) |

| ن.م.إ. (الإسمي) | تقدير 2023 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $92.210 billion[4] (94th) |

• للفرد | ▲ $3,474[4] (145th) |

| جيني (2013) | ▲ 44.8[5] medium |

| م.ت.ب. (2022) | ▲ 0.699[6] medium · 119th |

| العملة | Venezuelan bolívar (VED) (official) United States dollar (USD) (de facto recognized, unofficial) |

| التوقيت | UTC−04:00 (VET) |

| صيغة التاريخ | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| جانب السواقة | right |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +58 |

| النطاق العلوي للإنترنت | .ve |

| |

ڤنزويلا (/ˌvɛnəˈzweɪlə/ (![]() استمع) VEN-ə-ZWAYL-ə، النطق الإسپاني: [be.neˈswe.la])، تسمى رسمياً جمهورية ڤنزويلا البوليڤارية[1] (إسپانية: República Bolivariana de Venezuela النطق الإسپاني: [reˈpu.βlika βoliβaˈɾjana ðe βeneˈswela])، هي بلد على الساحل الشمالي لأمريكا الجنوبية. تبلغ مساحة أراضي ڤنزويلا 916.445 كم² ويقدر عدد سكانها بحوالي 20.100.000 نسمة. تعتبر ڤنزويلا دولة ذات تنوع حيوي كبير، بموئل يتمتد من جبال الأنديز في الغرب حتى حوض الأمازن في الجنوب، مروراً بسهول اللانوس والساحل الكاريبي في الوسط ودلتا نهر أورينكو في الشرق. The continental territory is bordered on the north by the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Colombia, Brazil on the south, Trinidad and Tobago to the north-east and on the east by Guyana. Venezuela is a presidential republic consisting of 23 states, the Capital District and federal dependencies covering Venezuela's offshore islands. Venezuela is among the most urbanized countries in Latin America;[7][8] the vast majority of Venezuelans live in the cities of the north and in the capital.

استمع) VEN-ə-ZWAYL-ə، النطق الإسپاني: [be.neˈswe.la])، تسمى رسمياً جمهورية ڤنزويلا البوليڤارية[1] (إسپانية: República Bolivariana de Venezuela النطق الإسپاني: [reˈpu.βlika βoliβaˈɾjana ðe βeneˈswela])، هي بلد على الساحل الشمالي لأمريكا الجنوبية. تبلغ مساحة أراضي ڤنزويلا 916.445 كم² ويقدر عدد سكانها بحوالي 20.100.000 نسمة. تعتبر ڤنزويلا دولة ذات تنوع حيوي كبير، بموئل يتمتد من جبال الأنديز في الغرب حتى حوض الأمازن في الجنوب، مروراً بسهول اللانوس والساحل الكاريبي في الوسط ودلتا نهر أورينكو في الشرق. The continental territory is bordered on the north by the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Colombia, Brazil on the south, Trinidad and Tobago to the north-east and on the east by Guyana. Venezuela is a presidential republic consisting of 23 states, the Capital District and federal dependencies covering Venezuela's offshore islands. Venezuela is among the most urbanized countries in Latin America;[7][8] the vast majority of Venezuelans live in the cities of the north and in the capital.

The territory of Venezuela was colonized by Spain in 1522 amid resistance from Indigenous peoples. In 1811, it became one of the first Spanish-American territories to declare independence from the Spanish and to form part of the first federal Republic of Colombia (Gran Colombia). It separated as a full sovereign country in 1830. During the 19th century, Venezuela suffered political turmoil and autocracy, remaining dominated by regional military dictators until the mid-20th century. From 1958, the country had a series of democratic governments, as an exception where most of the region was ruled by military dictatorships, and the period was characterized by economic prosperity.

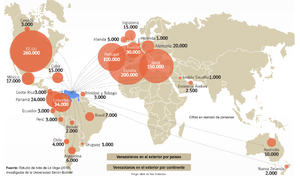

Economic shocks in the 1980s and 1990s led to major political crises and widespread social unrest, including the deadly Caracazo riots of 1989, two attempted coups in 1992, and the impeachment of a President for embezzlement of public funds charges in 1993. The collapse in confidence in the existing parties saw the 1998 Venezuelan presidential election, the catalyst for the Bolivarian Revolution, which began with a 1999 Constituent Assembly, where a new Constitution of Venezuela was imposed. The government's populist social welfare policies were bolstered by soaring oil prices,[9] temporarily increasing social spending,[10] and reducing economic inequality and poverty in the early years of the regime.[11] However, poverty began to rapidly increase in the 2010s.[12][13] The 2013 Venezuelan presidential election was widely disputed leading to widespread protest, which triggered another nationwide crisis that continues to this day.[14] Venezuela has experienced democratic backsliding, shifting into an authoritarian state.[15] It ranks low in international measurements of freedom of the press and civil liberties and has high levels of perceived corruption.[16] Venezuela is a developing country and has the world's largest known oil reserves and has been one of the world's leading exporters of oil. Previously, the country was an underdeveloped exporter of agricultural commodities such as coffee and cocoa, but oil quickly came to dominate exports and government revenues. The excesses and poor policies of the incumbent government led to the collapse of Venezuela's entire economy.[17][18] The country struggles with record hyperinflation,[19][20] shortages of basic goods,[21] unemployment,[22] poverty,[23] disease, high child mortality, malnutrition, environmental issues, severe crime and corruption. These factors have precipitated the Venezuelan refugee crisis in which more than 7.7 million people had fled the country by June 2024.[24][25] By 2017, Venezuela was declared to be in default regarding debt payments by credit rating agencies.[26][27] The crisis in Venezuela has contributed to a rapidly deteriorating human rights situation.

The 2024 presidential election were not recognized by the Carter Center and Organization of American States due to the lack of granular results, and disputed by the opposition, leading to protests across the country.[28]

التسمية

يعتقد أن اسم ڤنزويلا جاء من أميريگو ڤسبوتشي ومعه ألونسو دي أوخيدا، عندما قادا الحملة البحرية عام 1499، عبر الساحل الشمالي الغربي لخليج ڤنزويلا. وعندما بلغوا شبه جزيرة خواخيرا، لاحظوا القرى (البلافيتوس) المقامة والمبنية (التي شيدها الناس) على الماء. وذكر هذا ڤسبوتشى بمدينة البندقية (ڤينيزيا) بإيطاليا (وبالإيطالية: ڤينزيا)، ولذلك أسمى المنطقة باسم فنزوولا ومعناها فينيسيا الصغيرة أي تصغير فينيسيا بالإيطالية. وفي الإسبانية يستعمل المقطع (زويلا) للتصغير مثل بلازا : بلازويلا، وكازو : كازويلا. أما مارتين فرنانديز دى إنسيسو فقال وهو عضو في فريق فسبوتشى وأوجيدا، في كتابه سوما دى جيوجرافيا : إن أهل المنطقة اسمهم من الأصل فنزويلا، وأنها مشتقة من كلمة محلية. لكن تبقى قصة فسبوتشى هي الأكثر شيوعاً وقبولاً عن أصل اسم الدولة.[29][29][30][31]

التاريخ

التاريخ قبل كلومبس

Evidence exists of human habitation in the area now known as Venezuela from about 15,000 years ago. Tools have been found on the high riverine terraces of the Rio Pedregal in western Venezuela.[32] Late Pleistocene hunting artifacts, including spear tips, have been found at a similar series of sites in northwestern Venezuela; according to radiocarbon dating, these date from 13,000 to 7,000 BC.[33]

It is unknown how many people lived in Venezuela before the Spanish conquest; it has been estimated at one million.[34] In addition to Indigenous peoples known today, the population included groups such as the Kalina (Caribs), Auaké, Caquetio, Mariche, and Timoto–Cuicas. The Timoto–Cuica culture was the most complex society in Pre-Columbian Venezuela, with pre-planned permanent villages, surrounded by irrigated, terraced fields.[35] Their houses were made of stone and wood with thatched roofs. They were peaceful and depended on growing crops. Regional crops included potatoes and ullucos.[36] They left behind art, particularly anthropomorphic ceramics, but no major monuments. They spun vegetable fibers to weave into textiles and mats for housing. They are credited with having invented the arepa, a staple in Venezuelan cuisine.[37]

After the conquest, the population dropped markedly, mainly through the spread of infectious diseases from Europe.[34] Two main north–south axes of pre-Columbian population were present, who cultivated maize in the west and manioc in the east.[34] Large parts of the llanos were cultivated through a combination of slash and burn and permanent settled agriculture.[34]

الاستعمار

قام الأميرال كريستوفر كولومبوس في عام 1498 برحلته الثالثة إلى العالم الجديد، مُبحراً إلى شواطئ دلتا الأورينوكو لكى يتسلل بعد ذلك إلى خليج باريا، سامحاً له بذلك إكتشاف لأول مرة الساحل القارى. بروعة، أعرب كولون في رسالته إلى الملوك الكاثوليك عن ثقته في وصولة الجنة الأرضية ومُختلطاً عليه بسبب ملوحة المياه الغير عادية، كتب:

استعمر الإسپان ڤنزويلا في بداية القرن الميلادي السادس عشر، واستمر استعمارهم لها أكثر من ثلاثة قرون، وقامت ضد الحكم الإسباني عدة ثورات بزعامة سيمون بوليڤار، حيث قام الإستعمار الإسپاني بتقسيم ڤنزويلا إلى مقاطعات ولكُُُل مقاطعة حاكم، ويرأس حكام المقاطعات حاكم عام، وعلى أساس من إحكام القبضة الإستعمارية على الإقليم الفنزويلى، تأسس إقتصاد إستعمارى يستخرج المعادن وينتج المحاصيل لصالح التاج الأسبانى فقط. وكان للتجارة، رأس المال التجارى (ن - س - Δ ن) الدور الأكبر في التراكم، وكان الذهب والمعادن النفيسة الأخرى من أهم الدعامات التى عملت على ترسيخ دورة رأس المال التجارى في تلك المرحلة من التاريخ الفنزويلى.

الاستقلال

استقلت البلاد عام 1830، وذلك بعد أن انفصلت عن جمهورية كولومبيا الكبري، والتي تكونت عام 1821. قاد سيمون بوليڤار حروب الاستقلال في بلاده ڤنزويلا التي اعترفت بالجميل، فكان اسمها الرسمي جمهورية فنزويلا البوليفارية، وأطلقت اسمه على عملتها الرسمية وعلى أهم الشوارع والميادين والجامعات والمدارس والصروح الثقافية والعلمية بمدنها المختلفة، كما نُصِّبت تماثيله في كل مكان، حقبة الاستعمار الإسباني التي بدأت عام 1520 أنهتها ثورة سيمون بوليفار عام 1821 التي أعلنت قيام كولمبيا الكبرى المكونة من كولمبيا والإكوادور، قبل أن تعلن فنزويلا قيامها كدولة مستقلة عام 1830 على مساحة من الأرض تبلغ حوالي المليون كيلو متر مربع، تقع على الساحل الشمالي لأميركا الجنوبية، حيث تلتقي القارة الأميركية بالبحر الكاريبي.[38]

بعد حصولها على الاستقلال عام 1811 بعد حروب التحرير الدامية التي خاضها المحرر سيمون دي بوليفار خلال القرن التاسع عشر، وما أعقبها بعد ذلك من دكتاتوريات عسكرية، انتقلت فنزويلا مثل غيرها من بقية أراضي أمريكا اللاتينية من الخضوع المباشر للإمبراطورية الإسبانية إلى الخضوع غير المباشر لها، وكأن شيئا لم يكن، حيث تولت السلطة طبقة مكونة من البيض المنتمين إلى أوروبا بشكل عام أو من يطبقون عليهم هناك اسم "الكيوريوس" المنتمين إلى إسبانيا باعتبارهم يحملون وراثة الدم والعرق، أما الشعوب الأصلية لتلك البلاد فقد عاشوا ولا يزالون في تجمعات منعزلة بعيدا على ضفاف الأنهار أو في أعماق الغابات.[39]

After unsuccessful uprisings, Venezuela, under the leadership of Francisco de Miranda, a Venezuelan marshal who had fought in the American and French Revolutions, declared independence as the First Republic of Venezuela on 5 July 1811.[40] This began the Venezuelan War of Independence. A devastating 1812 Caracas earthquake, together with the rebellion of the Venezuelan llaneros, helped bring down the republic.[41] Simón Bolívar, new leader of the independentist forces, launched his Admirable Campaign in 1813 from New Granada, retaking most of the territory and being proclaimed as El Libertador ("The Liberator"). A Second Republic of Venezuela was proclaimed on 7 August 1813, but lasted only a few months before being crushed by royalist caudillo José Tomás Boves and his personal army of llaneros.[42]

The end of the French invasion of homeland Spain in 1814 allowed a large expeditionary force to come under general Pablo Morillo, with the goal to regain the lost territory in Venezuela and New Granada. As the war reached a stalemate on 1817, Bolívar reestablished the Third Republic of Venezuela on the territory still controlled by the patriots, mainly in the Guayana and Llanos regions. This republic was short-lived as only two years later, during the Congress of Angostura of 1819, the union of Venezuela with New Granada was decreed to form the Republic of Colombia. The war continued until full victory and sovereignty was attained after the Battle of Carabobo on 24 June 1821.[43] On 24 July 1823, José Prudencio Padilla and Rafael Urdaneta helped seal Venezuelan independence with their victory in the Battle of Lake Maracaibo.[2] New Granada's congress gave Bolívar control of the Granadian army; leading it, he liberated several countries and founded the Republic of Colombia (Gran Colombia).[43]

Sucre went on to liberate Ecuador and become the second president of Bolivia. Venezuela remained part of Gran Colombia until 1830, when a rebellion led by José Antonio Páez allowed the proclamation of a newly independent Venezuela, on 22 September;[44] Páez became the first president of the new State of Venezuela.[45] Between one-quarter and one-third of Venezuela's population was lost during these two decades of war (including about half the Venezuelans of European descent),[46] which by 1830, was estimated at 800,000.[47] In the Flag of Venezuela, the yellow stands for land wealth, the blue for the sea that separates Venezuela from Spain, and the red for the blood shed by the heroes of independence.[48]

Slavery in Venezuela was abolished in 1854.[47] Much of Venezuela's 19th-century history was characterized by political turmoil and dictatorial rule, including the Independence leader José Antonio Páez, who gained the presidency three times and served 11 years between 1830 and 1863. This culminated in the Federal War (1859–63). In the latter half of the century, Antonio Guzmán Blanco, another caudillo, served 13 years, between 1870 and 1887, with three other presidents interspersed.

In 1895, a longstanding dispute with Great Britain about the Essequibo territory, which Britain claimed as part of British Guiana and Venezuela saw as Venezuelan territory, erupted into the Venezuela Crisis of 1895. The dispute became a diplomatic crisis when Venezuela's lobbyist, William L. Scruggs, sought to argue that British behavior over the issue violated the United States' Monroe Doctrine of 1823, and used his influence in Washington, D.C., to pursue the matter. Then, U.S. president Grover Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the doctrine that declared an American interest in any matter within the hemisphere.[49] Britain ultimately accepted arbitration, but in negotiations over its terms was able to persuade the U.S. on many details. A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the issue and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[50]

In 1899, Cipriano Castro, assisted by his friend Juan Vicente Gómez, seized power in Caracas. Castro defaulted on Venezuela's considerable foreign debts and declined to pay compensation to foreigners caught up in Venezuela's civil wars. This led to the Venezuela Crisis of 1902–1903, in which Britain, Germany and Italy imposed a naval blockade before international arbitration at the new Permanent Court of Arbitration was agreed. In 1908, another dispute broke out with the Netherlands, which was resolved when Castro left for medical treatment in Germany and was promptly overthrown by Juan Vicente Gómez (1908–35).

القرن 20

بعد ظهور البترول في مناطق شمال شرق فنزويلا قام النظام الديمقراطي الذي يعتمد على حزبين رئيسيين حكما البلاد بالتبادل في ما بينهما منذ العام 1952، ولكن هذين الحزبين عملا خلال ما يزيد عن أربعين عاما على إبقاء حالة من القمع والفساد القائمة قبل وصول الديمقراطية، وتقاسم الحزبان الحكم ومعه عوائد البترول وتخزينها في البنوك الأميركية والسويسرية، في حين بقي الشعب في معظمه يعيش في حالة الفقر المدقع، فقد ظلت فنزويلا رغم عوائد البترول الضخمة تفتقر إلى الخدمات الأساسية من صحة وتعليم وطرق ومياه عذبة وكهرباء، رغم أنها تعتبر ثالث دولة منتجة للنفط ورابع دولة مصدرة له، حتى آخر حكومة تقليدية قبل أنتخابات العام 1998 التي جاءت بالكولونيل هوگو تشاڤيز لتمثل 80% من مجموع السكان البالغ عددهم 24 مليون نسمة.[39]

The discovery of massive oil deposits in Lake Maracaibo during World War I[51] proved pivotal for Venezuela and transformed its economy from a heavy dependence on agricultural exports. It prompted a boom that lasted into the 1980s; by 1935, Venezuela's per capita gross domestic product was Latin America's highest.[52] Gómez benefited handsomely from this, as corruption thrived, but at the same time, the new source of income helped him centralize the state and develop its authority.

Gómez remained the most powerful man in Venezuela until his death in 1935. The gomecista dictatorship (1935–1945) system largely continued under Eleazar López Contreras, but from 1941, under Isaías Medina Angarita, was relaxed. Angarita granted a range of reforms, including the legalization of all political parties. After World War II, immigration from Southern Europe and poorer Latin American countries markedly diversified Venezuelan society.[53]

In 1945, a civilian-military coup overthrew Medina Angarita and ushered in a period of democratic rule (1945–1948) under the mass membership party Democratic Action, initially under Rómulo Betancourt, until Rómulo Gallegos won the 1947 Venezuelan presidential election (the first free and fair elections in Venezuela).[54][55] Gallegos governed until overthrown by a military junta led by the triumvirate Luis Felipe Llovera Páez, Marcos Pérez Jiménez, and Gallegos' Defense Minister, Carlos Delgado Chalbaud, in the 1948 Venezuelan coup d'état.

The most powerful man in the military junta (1948–58) was Pérez Jiménez and he was suspected of being behind the death of Chalbaud, who died in a bungled kidnapping in 1950. When the junta unexpectedly lost the 1952 presidential election, it ignored the results and Jiménez was installed as president[citation needed] Jiménez was forced out on 23 January 1958.[2] In an effort to consolidate a young democracy, the three major political parties (Acción Democrática (AD), COPEI and Unión Republicana Democrática (URD), with the notable exception of the Communist Party of Venezuela), signed the Puntofijo Pact power-sharing agreement. AD and COPEI dominated the political landscape for four decades.

During the presidencies of Rómulo Betancourt (1959–64, his second term) and Raúl Leoni (1964–69), substantial guerilla movements occurred. Most laid down their arms under Rafael Caldera's first presidency (1969–74). Caldera had won the 1968 election for COPEI, the first time a party other than Democratic Action took the presidency through a democratic election. The new democratic order had its antagonists. Betancourt suffered an attack planned by the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1960, and the leftists excluded from the Pact initiated an insurgency by organizing themselves into the Armed Forces of National Liberation, sponsored by the Communist Party and Fidel Castro. In 1962 they tried to destabilize the military corps, with failed revolts. Betancourt promoted a foreign policy, the Betancourt Doctrine, in which he only recognized elected governments by popular vote.[need quotation to verify]

The 1973 Venezuelan presidential election of Carlos Andrés Pérez coincided with an oil crisis, in which Venezuela's income exploded as oil prices soared; oil industries were nationalized in 1976. This led to massive increases in public spending, but also increases in external debts, until the collapse of oil prices during the 1980s crippled the economy. As the government started to devalue the currency in 1983 to face its financial obligations, standards of living fell dramatically. Failed economic policies and increasing corruption in government led to rising poverty and crime, worsening social indicators, and increased political instability.[56]

In the 1980s, the Presidential Commission for State Reform (COPRE) emerged as a mechanism of political innovation. Venezuela decentralized its political system and diversified its economy, reducing the size of the state. COPRE operated as an innovation mechanism, also by incorporating issues into the political agenda, that were excluded from public deliberation by the main actors of the democratic system. The most discussed topics were incorporated into the public agenda: decentralization, political participation, municipalization, judicial order reforms and the role of the state in a new economic strategy. The social reality made the changes difficult to apply.[57]

Economic crises in the 1980s and 1990s led to a political crisis. Hundreds of people were killed by security forces and the military in the Caracazo riots of 1989, during the second presidential term of Carlos Andrés Pérez (1989–1993) and after the implementation of economic austerity measures.[58] Hugo Chávez, who in 1982 had promised to depose the bipartisanship governments, used the growing anger at economic austerity measures to justify a coup attempt in February 1992;[59][60] a second coup d'état attempt occurred in November.[60] President Carlos Andrés Pérez (re-elected in 1988) was impeached under embezzlement charges in 1993, leading to the interim presidency of Ramón José Velásquez (1993–1994). Coup leader Chávez was pardoned in March 1994 by president Rafael Caldera (1994–1999, his second term), with a clean slate and his political rights reinstated, allowing Chávez to win and maintain the presidency continuously from 1999 until his death in 2013. Chávez won the elections of 1998, 2000, 2006 and 2012 and the presidential referendum of 2004.

Bolivarian government under Chávez: 1999–2013

A collapse in confidence in the existing parties led to Hugo Chávez being elected president in 1998 and the subsequent launch of a "Bolivarian Revolution", beginning with a 1999 constituent assembly to write a new Constitution. The Revolution refers to a left-wing populism social movement and political process led by Chávez, who founded the Fifth Republic Movement in 1997 and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela in 2007. The "Bolivarian Revolution" is named after Simón Bolívar. According to Chávez and other supporters, the "Bolivarian Revolution" sought to build a mass movement to implement Bolivarianism—popular democracy, economic independence, equitable distribution of revenues, and an end to political corruption. They interpret Bolívar's ideas from a populist perspective, using socialist rhetoric. This led to formation of the Fifth Republic of Venezuela, commonly known as the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, that continues to the present day. Venezuela has been considered the Bolivarian Republic following the adoption of the new Constitution of 1999. Following Chávez's election, Venezuela developed into a dominant-party system, dominated by the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. In April 2002, Chávez was briefly ousted from power in the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt following popular demonstrations by his opponents,[61] but Chavez returned after two days as a result of demonstrations by poor Chávez supporters and actions by the military.[62][63] Chávez remained in power after an all-out national strike that lasted from December 2002 to February 2003, including a strike/lockout in the state oil company PDVSA.[64] Capital flight before and during the strike led to the reimposition of currency controls. In the subsequent decade, the government was forced into currency devaluations.[65][66][67][68] These devaluations did not improve the situation[vague] of the people who rely on imported products or locally produced products that depend on imported inputs, while dollar-denominated oil sales account for the majority of exports.[69] The profits of the oil industry have been lost to "social engineering" and corruption, instead of investments needed to maintain oil production.[70]

Chávez survived further political tests, including an August 2004 recall referendum. He was elected for another term in December 2006 and for a third term in October 2012. However, he was never sworn in due to medical complications; he died in March 2013.[71]

Bolivarian government under Maduro: 2013–present

The presidential election that took place in April 2013, was the first since Chávez took office in 1999 in which his name did not appear on the ballot.[72][نشر ذاتي سطري?] Under the Bolivarian government, Venezuela went from being one of the richest countries in Latin America to one of the poorest.[73] Hugo Chávez's socioeconomic policies of relying on oil sales and importing goods resulted in large amounts of debt, no change to corruption in Venezuela and culminated into a crisis in Venezuela.[73] As a result, the Venezuelan refugee crisis, the largest emigration of people in Latin America's history,[74] occurred, with over 7 million – about 20% of the country's population – emigrating.[75][76] Chávez initiated Bolivarian missions, programs aimed at helping the poor.[77]

Poverty began to increase into the 2010s.[12] Nicolás Maduro was picked by Chavez as his successor, appointing him vice president in 2013.[67][78][79]

Maduro has been president of Venezuela since 14 April 2013, when he won the presidential election after Chavez' death, with 51% of the vote, against Henrique Capriles on 49%. The Democratic Unity Roundtable contested Maduro's election as fraud, but an audit of 56% of the vote showed no discrepancies,[80] and the Supreme Court of Venezuela ruled Maduro was the legitimate president.[81] Opposition leaders and some international media consider Maduro's government a dictatorship.[82][83][84] Since February 2014, hundreds of thousands have protested over high levels of criminal violence, corruption, hyperinflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods due to government policies.[85][86][87] Demonstrations and riots have resulted in over 40 fatalities in the unrest between Chavistas and opposition protesters[88] and opposition leaders, including Leopoldo López and Antonio Ledezma were arrested.[88][89][90] Human rights groups condemned the arrest of López.[91] In the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary election, the opposition gained a majority.[92]

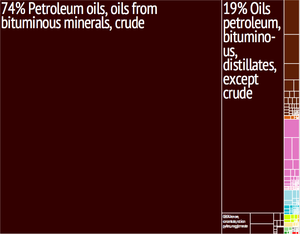

Venezuela devalued its currency in February 2013 due to rising shortages,[68][93] which included milk and other necessities. This led to an increase in malnutrition, especially among children.[94][95] The economy had become dependent on the exportation of oil, with crude accounting for 86% of exports,[96] and a high price per barrel to support social programs. Beginning in 2014 the price of oil plummeted from over $100 to $40. This placed pressure on the economy, which was no longer able to afford vast social programs. The Government began taking more money from PDVSA, the state oil company, resulting in a lack of reinvestment in fields and employees. Production decreased from its height of nearly 3 إلى 1 million برميل (480 إلى 160 thousand متر مكعب) per day.[97][98][99] In 2014, Venezuela entered a recession,[100] and in 2015, had the world's highest inflation, surpassing 100%.[101] In 2017, Donald Trump's administration imposed more economic sanctions against PDVSA and Venezuelan officials.[102][103][104] Economic problems, as well as crime, were the causes of the 2014–present Venezuelan protests.[105][106] Since 2014, roughly 5.6 million people have fled Venezuela.[107]

In January 2016, Maduro decreed an "economic emergency", revealing the extent of the crisis and expanding his powers.[108] In July 2016, Colombian border crossings were temporarily opened to allow Venezuelans to purchase food and basic health items.[109] In September 2016, a study[110] indicated 15% of Venezuelans were eating "food waste discarded by commercial establishments". 200 prison riots had occurred by October 2016.[111]

The Maduro-aligned Supreme Tribunal, which had been overturning National Assembly decisions since the opposition took control, took over the functions of the assembly, creating the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis.[82] In August 2017, the 2017 Constituent National Assembly was elected and stripped the National Assembly of its powers.[citation needed] The election raised concerns of an emerging dictatorship.[112] In December 2017, Maduro declared opposition parties barred from the following year's presidential vote after they boycotted mayoral polls.[113]

Maduro won the 2018 election with 68% of the vote. The result was challenged by Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Brazil, Canada, Germany, France and the US who deemed it fraudulent and recognized Juan Guaidó as president.[114][115][116] Other countries continued to recognize Maduro,[117][118] although China, facing financial pressure over its position, began hedging by decreasing loans, cancelling joint ventures, and signaling willingness to work with all parties.[119][120] In August 2019, Trump imposed an economic embargo against Venezuela.[121] In March 2020, Trump indicted Maduro and Venezuelan officials, on charges of drug trafficking, narcoterrorism, and corruption.[122]

In June 2020, a report documented enforced disappearances that occurred in 2018–19. 724 enforced disappearances of political detainees were reported. The report stated that security forces subjected victims to torture. The report stated the government used enforced disappearances to silence opponents and other critical voices.[123][124]

Maduro ran for a third consecutive term in the 2024 presidential election, while former diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia represented the Unitary Platform (إسپانية: Plataforma Unitaria Democrática; PUD), the main opposition political alliance.[125][126] Polls conducted before the election indicated that González would win by a wide margin. After the government-controlled National Electoral Council (CNE) announced partial results showing a narrow Maduro victory on 29 July, world leaders predominantly expressed skepticism of the claimed results and did not recognize the CNE claims[127][128] with only some exceptions.[129] Both González and Maduro proclaimed themselves winners of the election. The results of the election were not recognized by the Carter Center and Organization of American States due to the lack of granular results, and disputed by the opposition, which claimed a landslide victory and released access to vote tallies collected by poll watchers from a majority of polling centers as proof.[130][131][132][133]

In the aftermath of the announcement of results by the election authorities, protests broke out across the country.

الجغرافيا

الموقع

تقع ڤنزويلا على الساحل الشمالي لأمريكا الجنوبي بمحاذاة البحر الكاريبي، وتمتد سلاسل الجبال عبر رقعة واسعة من شمالي فنزويلا، وهو الإقليم الأكثر كثافة بالسكان في البلاد. وفي هذا الإقليم تقع العاصمة كراكاس، وهي أكبر المدن ويتجاوز عدد سكانها ثلاثة ملايين نسمة. وفي الجزء الأوسط من ڤنزويلا تمتد سهول واسعة هي سهول اللانوس، كما أنّ النجود المرتفعة والجبال القليلة الارتفاع تغطي الجزء الجنوبي من البلاد. وهي تحتلّ المرتبة الخامسة من حيث المساحة بين دول أمريكا الجنوبية، وتمتد بين خطي العرض 1 ْ و12 ْ شمالاً، وتطلّ على البحر الكاريبي بواجهة بحرية طولها نحو 2800 كم، ويجاورها كل من غيانا، والبرازيل، وكولومبيا. وتمتد بين خطي طول 30 َ 60 ْ-2 َ 73 ْ غرب گرينتش.[134]

المناخ

تصف المناخ في ڤنزويلا بالتنوع، على الرغم من وقوع فنزويلا بالمنطقة المدارية، ويرجع هذا التنوع المناخي إلى العوامل التضاريسية. ويراوح المناخ بين المداري الرطب والجاف من ناحية، والحار والمعتدل من ناحية أخرى. فالمناطق الساحلية والمنخفضة تتصف بمناخ حار على مدار السنة ( متوسط الحرارة 25 ْم)، على حين تنخفض الحرارة في المناطق المرتفعة، (ويبلغ متوسطها 19.5 ْْم)، ويبدأ ظهور الثلج الدائم على ارتفاع 5000م فوق سطح البحر. يسقط معظم الهطل في فصل الصيف، تبعاً لاتجاه وارتفاع التضاريس، في المناطق الساحلية الشمالية، يميل المناخ للجفاف، حيث يبلغ متوسط الهطل 400مم، أو أكثر، وتزداد كمية الهطل في المناطق المرتفعة، فتصل إلى 1500مم تقريباً.

ونتيجة لفصلية الأمطار، وقلتها النسبية، تنمو الحشائش في معظم مناطق البلاد، وتتخللها في بعض المواقع الأشجار المدارية الرطبة، وخاصة في المناطق المنخفضة، أما في المناطق المرتفعة فتنمو بعض الغابات النفضية، حيث تنخفض درجة الحرارة وتغزر الأمطار.

السطح

يمكن تقسيم الأراضي الڤنزويليّة إلى المناطق التضاريسيّة الآتية:

- جبال الأنديز: يتكون معظمها من قوس جبلي كبير، بطول 960 كم، يمتد من حدود كولومبيا في الغرب باتجاه شبه جزيرة باريا Paria شمالاً، وتتضمن مجموعة من السلاسل الجبلية، من أهمها سييرا نيفادا دي مريدا Sierra Nivada de Mérida التي ترتفع إلى أكثر من 5000م، وتمثل الامتداد الشمالي الشرقي لجبال الأنديز، وكذلك المرتفعات الوسطى التي يراوح ارتفاعها بين 1300-3000م فوق سطح البحر، والتي توازي وسط الساحل الفنزويلي جنوب العاصمة كاراكاس، والمرتفعات الشمالية الشرقية، والتي ترتفع إلى 2100م تقريباً فوق سطح البحر. وتشغل هذه الجبال 12% من مساحة فنزويلا، وهي تمثل مركز الثقل السكاني في البلاد، بسبب اعتدال درجات الحرارة وغزارة الأمطار والأحواض الجبلية ذات التربة الخصبة.

- الأراضي المنخفضة في الشمال الشرقي من البلاد: تمتد هذه الأراضي حول بحيرة مراكايبو Maracaibo، وخليج فنزويلا التي تكوّن إقليماً طبيعياً منخفضاً تعزله مرتفعات الأنديز عن بقية فنزويلا، وعن كولومبيا أيضاً. وقد احتلّ هذا الإقليم أهمية اقتصادية، خاصة بعد اكتشاف النفط الخام فيه. ويذكر أن بحيرة مراكيبو هي بحيرة ذات مياه عذبة على الرغم من اتصالها بالبحر، وذلك بسبب هطل كميات كبيرة من المطر، إضافة إلى ما ينساب إليها من المياه عبر المجاري المائية المنحدرة من السفوح المجاورة.

- سهول الأورينوكو: وتعرف بسهول اللانوس أي الحشائش المدارية، وهي تمثّل حوضاً منخفضاً يجري فيه نهر الأورينوكو الذي يبلغ طوله 2700كم في أكثر المناطق ارتفاعاً، إضافة إلى روافده العديدة، ومنها نهرا أبور Apore وكاروني Carroni. وتنحدر هذه السهول نحو الشرق،حيث ينساب نهر الأورينوكو نحو البحر الكاريبي، ويعترض النهر بعض الشلالات من أهمها شلالات أنجل Angel على نهر شورن Churun أحد روافد نهر كاروني.

- مرتفعات گيانا: تحتّل هذه المرتفعات جنوب شرقي فنزويلا إلى الجنوب من نهر الأورينوكو، ويصل ارتفاعها إلى 2870م تقريباً في أكثر المناطق ارتفاعاً، وهي عبارة عن كتلة هضبية قديمة، تتكون من الصخور البلورية أو الصخور الرملية،وتنحدر الهضبة عموماً نحو الشمال، وتنساب مجموعة من المجاري المائية نحو الشمال والغرب في اتجاه نهر الأورينوكو، مما أدى إلى تمزيق سطح الهضبة إلى أجزاء منفصلة، وتعدُّ هذه المرتفعات من أقل مناطق فنزويلا سكاناً وأكثرها تخلّفاً.

التنوع الحيوي والحفاظ

Venezuela lies within the Neotropical realm; large portions of the country were originally covered by moist broadleaf forests. One of 17 megadiverse countries,[135] Venezuela's habitats range from the Andes Mountains in the west to the Amazon Basin rainforest in the south, via extensive llanos plains and Caribbean coast in the center and the Orinoco River Delta in the east. They include xeric scrublands in the extreme northwest and coastal mangrove forests in the northeast.[136] Its cloud forests and lowland rainforests are particularly rich.[137]

Animals of Venezuela are diverse and include manatees, three-toed sloth, two-toed sloth, Amazon river dolphins, and Orinoco Crocodiles, which have been reported to reach up to 6.6 m (22 ft) in length. Venezuela hosts a total of 1,417 bird species, 48 of which are endemic.[138] Important birds include ibises, ospreys, kingfishers,[137] and the yellow-orange Venezuelan troupial, the national bird. Notable mammals include the giant anteater, jaguar, and the capybara, the world's largest rodent. More than half of Venezuelan avian and mammalian species are found in the Amazonian forests south of the Orinoco.[139]

For the fungi, an account was provided by R.W.G. Dennis[140] which has been digitized and the records made available on-line as part of the Cybertruffle Robigalia database.[141] That database includes nearly 3,900 species of fungi recorded from Venezuela, but is far from complete, and the true total number of fungal species already known from Venezuela is likely higher, given the generally accepted estimate that only about 7% of all fungi worldwide have so far been discovered.[142]

Among plants of Venezuela, over 25,000 species of orchids are found in the country's cloud forest and lowland rainforest ecosystems.[137] These include the flor de mayo orchid (Cattleya mossiae), the national flower. Venezuela's national tree is the araguaney. The tops of the tepuis are also home to several carnivorous plants including the marsh pitcher plant, Heliamphora, and the insectivorous bromeliad, Brocchinia reducta.

Venezuela is among the top 20 countries in terms of endemism.[143] Among its animals, 23% of reptilian and 50% of amphibian species, including the Trinidad poison frog, are endemic.[143][144] Although the available information is still very small, a first effort has been made to estimate the number of fungal species endemic to Venezuela: 1334 species of fungi have been tentatively identified as possibly endemic.[145] Some 38% of the over 21,000 plant species known from Venezuela are unique to the country.[143]

Venezuela is one of the 10 most biodiverse countries on the planet, yet it is one of the leaders of deforestation due to economic and political factors. Each year, roughly 287,600 hectares of forest are permanently destroyed, and other areas are degraded by mining, oil extraction, and logging. Between 1990 and 2005, Venezuela officially lost 8.3% of its forest cover, which is about 4.3 million ha. In response, federal protections for critical habitat were implemented; for example, 20% to 33% of forested land is protected.[139] The country's biosphere reserve is part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves; five wetlands are registered under the Ramsar Convention.[146] In 2003, 70% of the nation's land was under conservation management in over 200 protected areas, including 43 national parks.[147] Venezuela's 43 national parks include Canaima National Park, Morrocoy National Park, and Mochima National Park. In the far south is a reserve for the country's Yanomami tribes. Covering 32،000 ميل مربع (82،880 متر كيلومربع), the area is off-limits to farmers, miners, and all non-Yanomami settlers.

Venezuela was one of the few countries that did not enter an INDC at COP21.[149][150] Many terrestrial ecosystems are considered endangered, specially the dry forest in the northern regions of the country and the coral reefs in the Caribbean coast.[151][152][153]

There are 105 protected areas in Venezuela, which cover around 26% of the country's continental, marine and insular surface.[citation needed]

Hydrography

The country is made up of three river basins: the Caribbean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean and Lake Valencia, which forms an endorheic basin.[154]

On the Atlantic side it drains most of Venezuela's river waters. The largest basin in this area is the extensive Orinoco basin[155] whose surface area, close to one million km2, is greater than that of the whole of Venezuela, although it has a presence of 65% in the country.

The size of this basin - similar to that of the Danube - makes it the third largest in South America, and it gives rise to a flow of some 33,000 m3/s, making the Orinoco the third largest in the world, and also one of the most valuable from the point of view of renewable natural resources. The Rio or Brazo Casiquiare is unique in the world, as it is a natural derivation of the Orinoco that, after some 500 km in length, connects it to the Negro River, which in turn is a tributary of the Amazon.

The Orinoco receives directly or indirectly rivers such as the Ventuari, the Caura, the Caroní, the Meta, the Arauca, the Apure and many others. Other Venezuelan rivers that empty into the Atlantic are the waters of the San Juan and Cuyuní basins. Finally, there is the Amazon River, which receives the Guainía, the Negro and others. Other basins are the Gulf of Paria and the Esequibo River. The second most important watershed is the Caribbean Sea. The rivers of this region are usually short and of scarce and irregular flow, with some exceptions such as the Catatumbo, which originates in Colombia and drains into the Maracaibo Lake basin. Among the rivers that reach the Maracaibo lake basin are the Chama, the Escalante, the Catatumbo, and the contributions of the smaller basins of the Tocuyo, Yaracuy, Neverí and Manzanares rivers.

A minimum drains to the Lake Valencia basin.[156] Of the total extension of the rivers, a total of 5400 km are navigable. Other rivers worth mentioning are the Apure, Arauca, Caura, Meta, Barima, Portuguesa, Ventuari and Zulia, among others.

The country's main lakes are Lake Maracaibo[157] -the largest in South America- open to the sea through the natural channel, but with fresh water, and Lake Valencia with its endorheic system. Other noteworthy bodies of water are the Guri reservoir, the Altagracia lagoon, the Camatagua reservoir and the Mucubají lagoon in the Andes.

الأقاليم الجغرافية

The Venezuelan natural landscape[158] is the product of the interaction of tectonic plates[158] that since the Paleozoic have contributed to its current appearance. On the formed structures, seven physical-natural units have been modeled, differentiated in their relief and in their natural resources.

The relief of Venezuela has the following characteristics: coastline with several peninsulas[159] and islands, adenas of the Andes mountain range (north and northwest), Lake Maracaibo (between the chains, on the coast);[160] Orinoco river delta,[161] region of peneplains and plateaus (tepui, east of the Orinoco) that together form the Guyanas massif (plateaus, southeast of the country).

The oldest rock formations in South America are found in the complex basement of the Guyanas highlands[162] and in the crystalline line of the Maritime and Cordillera massifs in Venezuela. The Venezuelan part of the Guyanas Altiplano consists of a large granite block of gneiss and other crystalline Archean rocks, with underlying layers of sandstone and shale clay.[163]

The core of granite and cordillera is, to a large extent, flanked by sedimentary layers from the Cretaceous,[164] folded in an anticline structure. Between these orographic systems there are plains covered with tertiary and quaternary layers of gravel, sands and clayey marls. The depression contains lagoons and lakes, among which is that of Maracaibo, and presents, on the surface, alluvial deposits from the Quaternary.[165]

Also known as the Cordillera de la Costa, stretches along Venezuela's northern coast. This region is known for its lush tropical rainforests, stunning coastal views, and a rich variety of flora and fauna. The intermountain depressions, or valleys, between the mountain ranges are often home to fertile agricultural land and vibrant communities. These valleys offer a stark contrast to the rugged mountains that rise dramatically from the coast.

Situated in northwestern Venezuela, the Lara-Falcón Highlands exhibit a terrain defined by plateaus and rolling hills. These highlands provide a significant contrast to the surrounding lowlands and coastal areas. The relief is characterized by gently sloping plateaus that support agriculture, including coffee and cacao cultivation. This region's semi-arid climate and picturesque landscapes make it an important agricultural and tourism center.

Encompass the basin of Lake Maracaibo and the plains surrounding the Gulf of Venezuela. This region offers two distinct plains—the northern one is relatively dry, while the southern one is humid and dotted with swamps. The relief here is primarily characterized by flat terrain, with the exception of some elevated areas near the lake. Lake Maracaibo itself sits in a depression, surrounded by oil-rich lands and productive agricultural areas.[160]

The Venezuelan Andes, part of the broader Andes mountain range, offer a striking relief with towering peaks, deep valleys, and fertile intermontane basins. Dominated by these corpulent mountain ranges, including Venezuela's highest peak, Bolívar Peak, the region's rugged and picturesque landscapes are defined by its high-altitude terrain.

The unique relief of this area finds its origins in the Last Glacial Period, where the interplay of repeated glacier advances and retreats sculpted the landscape, shaped by the cold, high-altitude climate. This glacial heritage has left a lasting imprint, with glaciers carving deep valleys and polishing rugged peaks, while sheltered intramontane valleys offer fertile soils and temperate microclimates, creating ideal conditions for agriculture and human settlement.

Los Llanos, or "the plains", are expansive sedimentary basins characterized by predominantly flat relief.[166] However, the eastern Llanos feature low-plateaus and the Unare depression, created through mesa erosion, adding diversity to the terrain. This region is subject to seasonal flooding, transforming the flat plains into a vast wetland during the rainy season. The relief here influences the region's unique ecosystems, including extensive grasslands and abundant wildlife.

The Guiana Shield boasts a varied relief shaped by geological processes over millions of years. This region encompasses peneplains, rugged mountain ranges, foothills, and the iconic tepuis, or table-top mountains. The tepuis stand as isolated, flat-topped plateaus that rise dramatically from the surrounding terrain. This unique relief contributes to the region's remarkable biodiversity and scientific significance.[162]

The Orinoco Delta's relief is characterized by a complex system of lands and waters. It consists of numerous channels, islands, and shifting sedimentary deposits. While the relief may appear relatively uniform, it conceals a dynamic environment influenced by seasonal flooding and sediment deposition. This complex deltaic relief supports diverse aquatic life and the livelihoods of Indigenous communities adapted to its ever-changing landscapes.[161]

يمكن تقسيم البلاد إلى أربعة أقاليم جغرافية:

- إقليم المرتفعات الشمالية.

- إقليم حوض مراكيبو والأراضي الساحلية المنخفضة.

- إقليم سهول الأورينوكو.

- إقليم هضبة گيانا.

إقليم المرتفعات الشمالية

يحتلُّ هذا الإقليم نحو 25% من مساحة البلاد، ويضمُّ نحو 70% من مجمل سكان فنزويلا. ويعود هذا الحجم السكاني الكبير إلى المناخ الصحي اللطيف الذي تتمتع به المرتفعات، وعلى وجود الزراعة، ونمو مراكز العمران الحضري منذ وقت مبكر.

وتعدُّ الزراعة الحرفة الرئيسية التي يمارسها السكان، إذ بلغت نسبة العاملين في الزراعة نحو 7.8% من مجموع العاملين عام 2001، يزرعون قصب السكر والبن والكاكاو والقطن والمحاصيل الغذائية مثل الذرة والأرز والبطاطا والفول، كما يعمل السكان في تربية الحيوان وخاصة الأبقار والماعز.

ويضمُّ هذا الإقليم مدينة كراكاس عاصمة فنزويلا، أكبر مدينة فيها، وتقع على ارتفاع 1000م فوق سطح البحر، في حوض صغير، يبلغ طوله 24كم. وقد تطورت كراكاس بسرعة كبيرة بفضل الثروة النفطية، وتعدُّ المركز المالي والتجاري والإداري والصناعي للبلاد. وعلى بعد 96كم إلى الغرب من كراكاس يقع حوض فالنسيا Valencia الكبير الذي يضم مدينة فالنسيا، وهي مدينة صناعية مهمة.

إقليم حوض مراكيبو والأراضي الساحلية المنخفضة

يتضمن حوض مراكيبو الأراضي المحيطة بالبحيرة، وتحيط به المرتفعات من الشرق والجنوب والغرب. وتتسم هذه الأراضي بارتفاع درجة الحرارة والرطوبة العالية، لكن الهطل ليس غزيراً، إذ يراوح بين 400مم في الشمال، ونحو 850مم في الجنوب. فالشمال شبه جاف تمارس فيه زراعة بسيطة، أما الجنوب فتكثر فيه المستنقعات والغابات، ويزرع فيه قصب السكر والكاكاو وجوز الهند إلى جانب الذرة والأرز والموز، إلا أن اكتشاف النفط في هذا المنخفض رفع من شأنه ودفع البلاد جميعاً إلى مقدمة الدول المنتجة للنفط في العالم. وقد أدى الكشف النفطي إلى التحول السريع والشامل في حياة الإقليم. ولم تمض سنوات قليلة على اكتشاف النفط في عام 1917 حتى أصبحت سواحل بحيرة مراكيبو والبحيرة ذاتها بمنزلة غابة من أبراج النفط، وتحوّلت القرى المبعثرة حول البحيرة إلى مدن نفطية مزدهرة، وتنتج هذه المنطقة القسط الأكبر من الإنتاج النفطي للبلاد.

تتركّز الحقول النفطية على طول الشواطئ الشمالية الشرقية للبحيرة، مع وجود بعض الحقول إلى الغرب، والجنوب الغربي على طول الأراضي المنخفضة الساحلية لخليج فنزويلا. وتمتدُّ شبكة من خطوط الأنابيب لنقل النفط إلى شبه جزيرة باراغوانا Paraguana حيث معامل التكرير عند كاردون Cardon وآمـواي Amuay، كما ترسل كميات كبيرة من الإنتاج إلى الجزر الهولندية القريبة من جزيرة أروبا Aroba وكراكاو Curaçao حيث تتوزّع فيها معامل التكرير التي تعمل في خدمة النفط الفنزويلي. وتعدُّ مدينة مراكيبو المدينة الوحيدة ذات الأهمية الحقيقية في الإقليم، فهي ميناء لتصدير المشتقات النفطية والنفط الخام، إلى جانب تصدير البن الذي يتجمع فيها من منطقة المرتفعات الشمالية. وتعدُّ مدينة لاگويرا La Guaira الميناء الرئيس لفنزويلا، وعلى الرغم من أنها مدينة قديمة منذ الأيام الأولى للاستعمار، إلا أنها ظلَّت محدودة ومتخلفة حتى تمَّ كشف النفط.

تعدُّ دلتا نهر الأورينوكو جزءاً من المناطق المنخفضة الساحلية، وتتكوّن من سهول رسوبية مستوية واسعة تغطيها الغابات المدارية المطيرة، وبعض غابات المنغروف. وهي منطقة قليلة السكان، وأهم المدن هنا هي مدينة تكوبيتا Tucupita التي تعتمد في وجودها على بعض معامل تكرير النفط.

إقليم سهول الأورينوكو

يتكون هذا الإقليم من سهول واسعة، وتحيط بهذه السهول مرتفعات الأنديز من الشمال والغرب، وهضبة غيانا من الجنوب. وتشتهر هذه السهول بكونها نطاقاً مهماً من الحشائش، وكلمة اللانوس تعني أرض الحشائش، لذلك يتَّصف الإقليم بمطره الصيفي وشتائه الجاف، إذ تراوح كمية الهطل بين 400-800مم، ويعدُّ الإقليم منطقة رعي شاسعة، تربَّى فيه الماشية التي تمثِّل النشاط الرئيس. ويشكِّل هذا الإقليم نحو ثلث مساحة الأرض الفنزويلية.

استثمر الفحم الحجري في حوض نهر كاروني أحد روافد نهر الأورينوكو، وينقل بالخط الحديدي إلى الميناء النهري بالوا Palua على نهر الأورينوكو ثم بالسفن حتى شبه جزيرة باريا Paria، حيث يصدر من هناك. كما استغلت خامات الحديد في بالوا، والتي تضمُّ احتياطياً ضخماً من الفلزات تصل إلى نحو60%. والإقليم قليل السكان عامة، ومدنه صغيرة ومبعثرة، وهي عبارة عن مراكز تجارية للمناطق الزراعية.

إقليم هضبة گيانا

يحتلُّ هذا الإقليم الأراضي الهضبية المرتفعة جنوب حوض الأورينوكو. وقد تعرَّضت الهضبة لعمليات نحت وتعرية شديدة، حيث تنتشر الأودية الضيقة العميقة، وأدى موقع هذا الإقليم الداخلي ووعورة تضاريسه إلى جعله إقليماً منعزلاً يصعب الوصول إليه. ومن ثمَّ ظلَّ هذا الإقليم قليل السكان، وبعيداً عن الاهتمام للانتفاع بموارده لمدة طويلة. ولم تكن أهميته تتعدى إنتاج الذهب المحدود من منطقة الكالاو El Callao، والماس الذي يستخرج من التكوينات الرسوبية لوادي نهر كاروني. لكن أعمال المسح والتنقيب الحديثة كشفت عن وجود احتياطي ضخم من خام الحديد على الأطراف الشمالية للمرتفعات، حيث يعدن في منطقة الباو، وقامت في المنطقة صناعة الحديد والفولاذ.

الوديان

The valleys are undoubtedly the most important type of landscape in the Venezuelan territory,[167] not because of their spatial extension, but because they are the environment where most of the country's population and economic activities are concentrated. On the other hand, there are valleys throughout almost all the national space, except in the great sedimentary basins of the Llanos and the depression of the Maracaibo Lake, except also in the Amazonian peneplains.[168] By their modeling, the valleys of the Venezuelan territory belong mainly to two types: valleys of fluvial type and valleys of glacial type.[169] Much more frequent, the former largely dominate the latter, which are restricted to the highest parts of the Andes. Moreover, most glacial valleys are relics of a past geologic epoch, which culminated some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

The deep and narrow Andean valleys are very different from the wide depressions of Aragua and Carabobo, in the Cordillera de la Costa, or from the valleys nestled in the Mesas de Monagas. These examples indicate that the configuration of the local relief is decisive in identifying regional types of valleys. Likewise, due to their warm climate, the Guayana valleys are distinguished from the temperate or cold Andean valleys by their humid environment. Both are, in turn, different from the semi-arid depressions of the states of Lara and Falcón.

The Andean valleys, essentially agricultural, precociously populated but nowadays in loss of speed, do not confront the same problems of space occupation as the strongly urbanized and industrialized valleys of the central section of the Cordillera de la Costa. On the other hand, the unpopulated and practically untouched Guiana valleys are another category this area is called the Lost World (Mundo Perdido).[168]

The Andean valleys are undoubtedly the most impressive of the Venezuelan territory because of the energy of the encasing reliefs, whose summits often dominate the valley bottoms by 3,000 to 3,500 meters of relative altitude. They are also the most picturesque in terms of their style of habitat, forms of land use, handicraft production and all the traditions linked to these activities.[168]

الصحاري

Venezuela has a great diversity of landscapes and climates,[170] including arid and dry areas. The main desert in the country is in the state of Falcon near the city of Coro. It is now a protected park, the Médanos de Coro National Park.[171] The park is the largest of its kind in Venezuela, covering 91 square kilometres. The landscape is dotted with cacti and other xerophytic plants that can survive in humidity-free conditions near the desert.

Desert wildlife includes mostly lizards, iguanas and other reptiles. Although less frequent, the desert is home to some foxes, giant anteaters and rabbits. There are also some native bird populations, such as the sparrowhawk, tropical mockingbird, scaly dove and crested quail.

Other desert areas in the country include part of the Guajira Desert in the Guajira Municipality in the north of Zulia State[172] and facing the Gulf of Venezuela, the Médanos de Capanaparo[173] in the Santos Luzardo National Park in Apure State, the Medanos de la Isla de Zapara[174] in Zulia State, the so-called Hundición de Yay[175] in the Andrés Eloy Blanco Municipality of Lara State, and the Urumaco Formation also in Falcón State.

الحكومة والسياسة

جمهورية اتحادية تتكون من 22 ولاية، والإقليم الاتحادي ( كراكاس ) ، تابع اتحادي ( 72 جزيرة). يوجد برلمان ( الكونجرس ) من مجلسين:

- مجلس الشيوخ وعدد أعضائه خمسون

- مجلس النواب وعدد اعضائه مائة وتسع وتسعون. ينتخب كلا أعضاء المجلسين بالإقتراع العام المباشر لمدة خمس سنوات، ينتخب رئيس الجمهورية لمدة ست سنوات ولابد أن يكون فنزويلي المولد ويزيد عمره عن الثلاثين عام، ولا يجوز له أن يرشح نفسه لفترة ثانية متتابعة، ولكن يجوز له أن يعيد ترشيح نفسه بعد إنقضاء عشر سنوات من فترة رئاسته الاولى.

الأحزاب السياسية

حزب العمل الديموقراطي (يسار الوسط)، الحزب الاجتماعي المسيحي (يمين وسط)، حزب الحركة إتجاه الإشتراكية (يسار وسط)، حزب القضية الراديكالية (يسار)، حزب التلاقي الوطني (تجمع إئتلافي واسع).

العلاقات الخارجية

العسكرية

الجريمة والقانون

التقسيمات الادارية

| |||

| الولاية | العاصمة | الولاية | العاصمة |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puerto Ayacucho | مريدا | ||

| برشلونة | Los Teques | ||

| San Fernando de Apure | Maturín | ||

| Maracay | La Asunción | ||

| Barinas | Guanare | ||

| Ciudad Bolívar | Cumaná | ||

| Valencia | San Cristóbal | ||

| San Carlos | Trujillo | ||

| توكوپيتا | سان فليپه | ||

| كاراكاس | Maracaibo | ||

| كورو | La Guaira | ||

| San Juan de los Morros | El Gran Roque | ||

| Barquisimeto | |||

| 1 The Federal Dependencies are not states. They are just special divisions of the territory. | |||

ڤنزويلا تنقسم إل احدى وعشرين ولاية (إستادوس)، ومنطقة العاصمة وتوابع فدرالية (Dependencias Federales، وهي منطقة خاصة) وگويانا إسكويبا Guayana Esequiba وهي المتنازع عليها مع گويانا.[176]

أكبر المدن

| الترتيب | State | التعداد | الترتيب | State | التعداد | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Caracas Maracaibo |

1 | Caracas | Capital District | 2,904,376 | 11 | Ciudad Bolívar | Bolívar | 342,280 |  ڤالنسيا  Barquisimeto |

| 2 | Maracaibo | Zulia | 1,906,205 | 12 | San Cristóbal | Táchira | 263,765 | ||

| 3 | ڤالنسيا | كارابوبو | 1,396,322 | 13 | Cabimas | Zulia | 263,056 | ||

| 4 | Barquisimeto | Lara | 996,230 | 14 | Los Teques | ميراندا | 252,242 | ||

| 5 | Ciudad Guayana | بوليڤار | 706,736 | 15 | Puerto la Cruz | Anzoátegui | 244,728 | ||

| 6 | ماتورين | موناگاس | 542,259 | 16 | Punto Fijo | فالكون | 239,444 | ||

| 7 | Barcelona | Anzoátegui | 421,424 | 17 | ميريدا | ميريدا | 217,547 | ||

| 8 | Maracay | أراگوا | 407,109 | 18 | Guarenas | ميراندا | 209,987 | ||

| 9 | كومانا | سوكرى | 358,919 | 19 | Ciudad Ojeda | زوليا | 203,435 | ||

| 10 | باريناس | Barinas | 353.851 | 20 | Guanare | Portuguesa | 192,644 | ||

Foreign relations

Throughout most of the 20th century, Venezuela maintained friendly relations with most Latin American and Western nations. Relations between Venezuela and the United States government worsened in 2002, after the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt during which the U.S. government recognized the short-lived interim presidency of Pedro Carmona. In 2015, Venezuela was declared a national security threat by U.S. president Barack Obama.[178][179][180] Correspondingly, ties to various Latin American and Middle Eastern countries not allied to the U.S. have strengthened.[citation needed]

Venezuela seeks alternative hemispheric integration via such proposals as the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas trade proposal and the newly launched Latin American television network teleSUR. Venezuela is one of five nations in the world—along with Russia, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria—to have recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Venezuela was a proponent of OAS's decision to adopt its Anti-Corruption Convention[181] and is actively working in the Mercosur trade bloc to push increased trade and energy integration. Globally, it seeks a "multi-polar" world based on strengthened ties among undeveloped countries.[citation needed]

On 26 April 2017, Venezuela announced its intention to withdraw from the OAS.[182] Venezuelan Foreign Minister Delcy Rodríguez said that President Nicolás Maduro plans to publicly renounce Venezuela's membership on 27 April 2017. It will take two years for the country to formally leave. During this period, the country does not plan on participating in the OAS.[183]

Venezuela is involved in a long-standing disagreement about the control of the Guayana Esequiba area.

Venezuela may suffer a deterioration of its power in international affairs if the global transition to renewable energy is completed. It is ranked 151 out of 156 countries in the index of Geopolitical Gains and Losses after energy transition (GeGaLo).[184]

Venezuela is a charter member of the United Nations (UN), Organization of American States (OAS), Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), Mercosur, Latin American Integration Association (LAIA) and Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI).

Military

The Bolivarian National Armed Forces (Fuerza Armada Nacional Bolivariana, FANB) are the unified military forces of Venezuela. It includes over 320,150 men and women, under Article 328 of the Constitution, in five components of ground, sea and air. The components of the FANB are: the Venezuelan Army, the Venezuelan Navy, the Venezuelan Air Force, the Venezuelan National Guard, and the Venezuelan National Militia. اعتبارا من 2008[تحديث], a further 600,000 soldiers were incorporated into a new branch, known as the Armed Reserve.

The president of Venezuela is the commander-in-chief of the FANB. Its main purposes are to defend the sovereign national territory of Venezuela, airspace, and islands, fight against drug trafficking, search and rescue and, in the case of a natural disaster, civil protection. All male citizens of Venezuela have a constitutional duty to register for the military service at 18, which is the age of majority.

Law and crime

Source: CICPC[190][191][192]

* Express kidnappings may not be included in data.

In Venezuela, a person is murdered every 21 minutes.[193] Violent crimes have been so prevalent in Venezuela that the government no longer produces the crime data.[194] In 2013, the homicide rate was approximately 79 per 100,000, one of the world's highest, having quadrupled in the past 15 years with over 200,000 people murdered.[195] By 2015, it had risen to 90 per 100,000.[196] The capital Caracas has one of the greatest homicide rates of any large city in the world, with 122 homicides per 100,000 residents.[197] In 2008, polls indicated that crime was the number one concern of voters.[198] Attempts at fighting crime such as Operation Liberation of the People were implemented to crack down on gang-controlled areas[199] but, of reported criminal acts, less than 2% are prosecuted.[200] In 2017, the Financial Times noted that some of the arms procured by the government over the previous two decades had been diverted to paramilitary civilian groups and criminal syndicates.[201]

Venezuela is especially dangerous for foreign travelers and investors who are visiting. The United States Department of State and the Government of Canada have warned foreign visitors that they may be subjected to robbery, kidnapping[202] and murder, and that their own diplomatic travelers are required to travel in armored vehicles.[203][204] The United Kingdom's Foreign and Commonwealth Office has advised against all travel to Venezuela.[205] Visitors have been murdered during robberies.[206][207]

There are approximately 33 prisons holding about 50,000 inmates.[208] Venezuela's prison system is heavily overcrowded; its facilities have capacity for only 14,000 prisoners.[209]

Human rights

Human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have increasingly criticized Venezuela's human rights record, with the former organization noting in 2017 that the Chavez and subsequently the Maduro government have increasingly concentrated power in the executive branch, eroded constitutional human rights protections and allowed the government to persecute and repress its critics and opposition.[210] Other persistent concerns as noted by the report included poor prison conditions, the continuous harassment of independent media and human rights defenders by the government. In 2006, the Economist Intelligence Unit rated Venezuela a "hybrid regime" and the third least democratic regime in Latin America on the Democracy Index.[211] The Democracy index downgraded Venezuela to an authoritarian regime in 2017, citing continued increasingly dictatorial behaviors by the Maduro government.[212]

Corruption

Corruption in Venezuela is high by world standards and was so for much of the 20th century. The discovery of oil worsened political corruption.[213] By the late 1970s, Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso's description of oil as "the Devil's excrement" had become a common expression in Venezuela.[214] The Corruption Perceptions Index has ranked Venezuela as one of the most corrupt countries since the survey started in 1995. The 2010 ranking placed Venezuela at number 164, out of 178 ranked countries in government transparency.[215] By 2016, the rank had increased to 166 out of 178.[216] The World Justice Project ranked Venezuela 99th out of 99 countries surveyed in its 2014 Rule of Law Index.[217]

This corruption is shown with Venezuela's significant involvement in drug trafficking, with Colombian cocaine and other drugs transiting Venezuela towards the United States and Europe. In the period 2003–2008 Venezuelan authorities seized the fifth-largest total quantity of cocaine in the world, behind Colombia, the United States, Spain and Panama.[218] In 2006, the government's agency for combating illegal drug trade in Venezuela, ONA, was incorporated into the office of the vice-president. However, many major government and military officials have been known for their involvement with drug trafficking.[219]

الاقتصاد

يعدُّ النفط أهم الموارد الاقتصادية في ڤنزويلا، إذ يسهم بأكثر من نصف الدخل الوطني. وقد بلغت نسبة العاملين في الزراعة عام 2001 نحو 7.8% من مجموع العاملين، علماً أن مساحة الأرض الصالحة للزراعة تبلغ نحو 4% من مساحة البلاد. وتبلغ نسبة الأرض المروية نحو 7% من مساحة الأرض الصالحة للزراعة. وتبلغ مساحة الغابات 34.5% من مجموع مساحة البلاد. ومازال بعض السكان يمارسون زراعة الحريق (طريقة قديمة للزراعة تقوم على إحراق الأرض قبل البدء بزراعتها للقضاء على الأعشاب الضارة وزيادة خصوبتها). وزاد الأمر سوءاً ما صاحب اكتشاف النفط من هجرة كثير من سكان الأرياف إلى المدن، للعمل في مجالات التعدين والصناعة والتجارة والخدمات.

النفط وموارد أخرى

بلغ إنتاج الذرة في ڤنزويلا 1504800 طن في عام 2003، كما بلغ إنتاج الأرز 600611 طناً. وبلغ إنتاج البوكسيت (4.826) مليون طن عام 1998، كما يعدَّن النحاس ويستخرج الإسفلت والفحم والملح وغيرها.

بلغ إنتاج ڤنزويلا من النفط الخام نحو 171924 ألف طن في عام 2001، محتلَّة المرتبة السادسة بين منتجي النفط الخام، كما بلغ إنتاج الغاز 27106 ألف طن مكعب في العام نفسه. وقد تطوَّر النشاط الصناعي حديثاً بمساعدة الدولة، فأقيمت صناعة الحديد والصلب والصناعات الكيمياوية وتجميع السيارات والأسمدة والصناعات النسيجية والغذائية والصناعات الجلدية. ومما ساعد على التطور توافر المواد الخام، وخاصة النفط والخامات المعدنية والزراعية والحيوانية.

السياحة

Tourism has been developed considerably in recent decades, particularly because of its favorable geographical position, the variety of landscapes, the richness of plant and wildlife, the culture and the tropical climate.

Margarita Island is one of the top tourist destinations. It is an island with a modern infrastructure, bordered by beaches suitable for extreme sports, and features castles, fortresses and churches of great cultural value.

Los Roques Archipelago is made up of a set of islands and keys that constitute one of the main tourist attractions in the country. With exotic crystalline beaches, Morrocoy is a national park, formed by small keys very close to the mainland, which have grown rapidly as one of the greatest tourist attractions in the Venezuelan Caribbean.[220]

Canaima National Park[221] extends over 30,000 km2 to the border with Guyana and Brazil; due to its size it is considered the sixth largest national park in the world. Its steep cliffs and waterfalls (including Angel Falls, which is the highest waterfall in the world, at 1,002 m) form spectacular landscapes.

The state of Mérida[222] is one of the main tourist centers of Venezuela. It has an extensive network of hotels not only in its capital city, but also throughout the state. Starting from the same city of Mérida is the longest and highest cable car in the world, which reaches the Pico Espejo of 4,765 m.

النقص

Shortages in Venezuela have been prevalent following the enactment of price controls and other policies during the economic policy of the Hugo Chávez government.[223][224] Under the economic policy of the Nicolás Maduro government, greater shortages occurred due to the Venezuelan government's policy of withholding United States dollars from importers with price controls.[225]

Shortages occur in regulated products, such as milk, various types of meat, coffee, rice, oil, flour, butter, and other goods including basic necessities like toilet paper, personal hygiene products, and even medicine.[223][226][227] As a result of the shortages, Venezuelans must search for food, wait in lines for hours and sometimes do without certain products.[228][229][230][231][232]

A drought, combined with a lack of planning and maintenance, has caused a hydroelectricity shortage. To deal with lack of power supply, in April 2016 the Maduro government announced rolling blackouts[233] and reduced the government workweek to only Monday and Tuesday.[234] A multi-university study found that, in 2016 alone, about 75% of Venezuelans lost weight due to hunger, with the average losing about 8.6 kg (19 lbs) due to the lack of food.[235] In March 2017, Venezuela began having shortages of gasoline in some regions.[236]

Petroleum and other resources

Venezuela has the largest oil reserves, and the eighth largest natural gas reserves in the world.[238] Compared to the preceding year another 40.4% in crude oil reserves were proven in 2010, allowing Venezuela to surpass Saudi Arabia as the country with the largest reserves of this type.[239] The country's main petroleum deposits are located around and beneath Lake Maracaibo, the Gulf of Venezuela (both in Zulia), and in the Orinoco River basin (eastern Venezuela), where the country's largest reserve is located. Besides the largest conventional oil reserves and the second-largest natural gas reserves in the Western Hemisphere,[240] Venezuela has non-conventional oil deposits (extra-heavy crude oil, bitumen and tar sands) approximately equal to the world's reserves of conventional oil.[241] The electricity sector in Venezuela is one of the few to rely primarily on hydropower, and includes the Guri Dam, one of the largest in the world.

In the first half of the 20th century, U.S. oil companies were heavily involved in Venezuela, initially interested only in purchasing concessions.[242] In 1943 a new government introduced a 50/50 split in profits between the government and the oil industry. In 1960, with a newly installed democratic government, Hydrocarbons Minister Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso led the creation of OPEC, the consortium of oil-producing countries aiming to support the price of oil.[243]

In 1973, Venezuela voted to nationalize its oil industry outright, effective 1 January 1976, with Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) taking over and presiding over a number of holding companies; in subsequent years, Venezuela built a vast refining and marketing system in the U.S. and Europe.[244] In the 1990s PDVSA became more independent from the government and presided over an apertura (opening) in which it invited in foreign investment. Under Hugo Chávez a 2001 law placed limits on foreign investment. PDVSA played a key role in the December 2002 – February 2003 national strike. As a result of the strike, around 40% of the company's workforce (around 18,000 workers) were dismissed.[245]

البنية التحتية

النقل

Venezuela is connected to the world primarily via air (Venezuela's airports include the Simón Bolívar International Airport in Maiquetía, near Caracas and La Chinita International Airport near Maracaibo) and sea (with major seaports at La Guaira, Maracaibo and Puerto Cabello). In the south and east the Amazon rainforest region has limited cross-border transport; in the west, there is a mountainous border of over 2،213 كيلومتر (1،375 mi) shared with Colombia. The Orinoco River is navigable by oceangoing vessels up to 400 كيلومتر (250 mi) inland and connects the major industrial city of Ciudad Guayana to the Atlantic Ocean.

Venezuela has a limited national railway system, which has no active rail connections to other countries. The government of Hugo Chávez tried to invest in expanding it, but Venezuela's rail project is on hold due to Venezuela not being able to pay the $7.5 billion[مطلوب توضيح] and owing China Railway nearly $500 million.[246] Several major cities have metro systems; the Caracas Metro has been operating since 1983. The Maracaibo Metro and Valencia Metro were opened more recently. Venezuela has a road network of nearly 100،000 كيلومتر (62،000 mi), placing the country around 45th in the world;[247] around a third of roads are paved.

المرافق

This section requires expansion. (April 2024) |

The electricity sector in Venezuela is heavily dependent on hydroelectricity, with this energy source accounting for 64% of the country's electricity generation in 2021.[237]

الديموغرافيا

| السنة | تعداد | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 5٬094٬000 | — |

| 1960 | 7٬562٬000 | +4.03% |

| 1970 | 10٬681٬000 | +3.51% |

| 1980 | 15٬036٬000 | +3.48% |

| 1990 | 19٬685٬000 | +2.73% |

| 2000 | 24٬348٬000 | +2.15% |

| 2011 | 28٬400٬000 | +1.41% |

| 2015 | 33٬221٬865 | +4.00% |

| [248][249] Source: الأمم المتحدة | ||

مقالة مفصلة: قائمة المناطق الكبرى في ڤنزويلا

مقالة مفصلة: قائمة المناطق الكبرى في ڤنزويلا

بلغ عدد سكان ڤنزويلا نحو 13122 ألف نسمة في عام 1978، ووصل العدد إلى 25017 ألف نسمة تقريباً في عام 2004. وبلغ معدل النمو السكاني 3.1% في الفترة من 1960 إلى 1991، ثم انحدر نمو السكان إلى 2% خلال الفترة من 1991 إلى 2000، وبلغ معدل الخصوبة الإجمالي نحو 2.3 للمرأة الواحدة. وتضم العاصمة نحو 16% من مجمل السكان الحضر.

يتركَّز السكان بصورة واضحة في منطقة المرتفعات الشمالية، حيث تضم نحو 70% من مجموع السكان، ويقطن نحو 10% من مجموع السكان حول خليج مراكيبو، بسبب وجود الثروة النفطية، ويرجع هذا إلى المناخ الصحي، وتوافر الترب الخصبة، ووجود الثروات النفطية، ويقطن في سهول الأورينوكو الواسعة نحو 18% من مجموع السكان. وعلى الرغم من أن المساحة التي تحتلها مرتفعات غيانا الجنوبية تمثل حوالي نصف مساحة فنزويلا، إلا أن مجمـوع سكانـها لا يتجاوز 2% من جملة سكان البلاد. وقد بلغ عدد سكان الحضر 94% من مجموع السكان عام 2000.

ويعود السكان الأصليون إلى القبائل الهندية، تأتي في مقدمتها قبائل المستيزو والذين يكونون غالبية السكان، ثم قبائل الأرواك Arawaks والكاريب Carib والمولاتو Mullatos، إلى جانب بعض القبائل الهندية البدائية، والذين يعيشون في المناطق الجبلية. وقد هاجر إلى فنزويلا كثير من الأوربيين وخاصة الإسبان والإيطاليين والفرنسيين والألمان ثمَّ العرب وغيرهم.

الجماعات العرقية

اللغات

الدين

الثقافة

الفن

الأدب

تعود بدايات الأدب الڤنزويلي إلى عهد الاستيطان الإسپاني في أمريكا الجنوبية في القرن السادس عشر ولأدباء كتبوا في الأجناس الأدبية كافة، وخاصة في الشعر مثل القس خوان كاستيانوس Juan Castellanos الذي كتب «مراثي» Elegias حول رجال القارة الكبار، وفي التاريخ مثل فراي پدرو دي أگوادو Fray Pedro de Aguado وفراي پدرو سيمون Fray Pedro Simón اللذين كتبا حول تاريخ البلاد وأطلقت على الأخير تسمية «هيرودوتس الڤنزويلي». ومع بداية محاولات الاستقلال عن إسبانيا في القرن الثامن عشر ظهر كتاب أسهموا في تنمية الفكر التحرري والخطابة والأدب، وكان سيمون بوليڤار Simón Bolivar أبرز هؤلاء، وتم على يديه تحرير أجزاء كبيرة من أمريكا اللاتينية من الحكم الإسباني، وكان آندريس بييّو Andrés Bello من أبرز المثقفين الذين أثّروا تأثيراً كبيراً داخل حدود بلادهم وخارجها.

ظهر بعد استقلال فنزويلا في القرن التاسع عشر كتاب كبار متنوعو المواهب مثل فرمين تورو Fermin Toro الذي كان روائياً وشاعراً وقاضياً، ورافائيل ماريا بارالت Rafael Maria Baralt المؤرخ والعالم اللغوي، وخوان بيثنته گونثالث Juan Vicente González اللغوي والهجَّاء. واتسمت الحقبة الإبداعية (الرومنسية) بالتركيز على الشعر فكتبت آبيگايل لوسانو Abigail Lozano شعراً غنائياً مرهفاً، وقام الشاعر خوان أنطونيو پيريث بونالده Juan Antonio Pérez Bonalde بترجمة كل من هاينه Heine وبو Poe إلى الإسبانية وآذن ببدء حركة الحداثة في الأدب. وقد كان للشعراء الوطنيين دور كبير في إرساء أركان الدولة الفتية وحشد الدعم الشعبي لها، ومن هؤلاء فرانشيسكو لاسو مارتي Francisco Lazo Marti الذي تغنى بالسهوب llanos، وأريستيدس روخاس Aristides Rojas الذي استعان بالتاريخ والطبيعة والعادات المحلية في سبيل دعم الحس الوطني، وگونسالو پيكون فيبرس Gonzalo Picón Febres الذي كتب الرواية التاريخية «الرقيب فيليبه» El Sargento Felipe، كما كتب كل من إدواردو بلانكو Eduardo Blanco رواية «زاراتيه» Zárate في النقد الاجتماعي اللاذع ومانويل بيثنته روميرو گارثيا Manuel Vicente Romero Garcia روايته الطبيعية «بيونيا» Peonía عام (1890) المشبعة باللون المحلي.

ظهرت مع بداية القرن العشرين دوريتا «إلكوهو إيوسترادو» El Cojo illustrado و«كوزموبوليس» Cosmópolis الناطقتين بلسان تيار الحداثة وتجمع حولهما العديد من أدباء الجيل الجديد ومنهم زعيم التيار روفينو بلانكو فومبونا Rufino Blanco Fombona، الذي سار على خطى روبن داريو Rubén Darío، وكتب دراسة «الحداثة وشعراؤها» El modernismo y los poetas modernistas عام (1929)، وعُرف برواياته المعبرة عن روح العصر مثل «رجل من الفولاذ»El hombre de hierro عام (1907) و«رجل من الذهب» El hombre de oro عام (1914)، ومانويل دياز رودريگز Manuel Díaz Rodríguez الذي كان بأسلوبه الرفيع أكبر كتاب التيار بروايات مثل «أوثان محطمة»Ídolos rotos عام (1901) وقصص قصيرة مثل «حكايات ألوان»Cuentos de color عام (1899)، وأيضاً تيريسا دي لابارا Teresa de la Parra التي تعد من الرائدات في الرواية النفسية الفنزويلية في «يومـيات صبية كتبت بسبب الملل» Diario de uña senorita que escribio porque se fastidia عـام (1924)، التي أعادت عنونتها لاحقاً «إفيجينيا» Ifigenia، و«تذكارات ماما بلانكا» Las memorias de Mamó Blanca عام (1929).

يعد رومولو گالييگوس Rómulo Gallegos عميداً للأدب الفنزويلي في القرن العشرين، كتب في الرواية والمسرحية والقصة القصيرة والمقالة. ركز في رواياته الكبيرة «السيدة باربارا» Doña Barbara عام (1929) و«المغني الشاب» cantaclaro عـام (1934) و«كانايما» Canaima عـام (1935) وفي مجموعة القصص القصيرة «المغامرون» Los aventureros عام (1913) على موضوعات محلية، وفتحت أمام مؤلفها باب الشهرة العالمية. كذلك برز أديب آخر من المستوى العالمي ذاته هو آرتورو أوسلار بييتري Arturo Uslar Pietri الذي كتب في الرواية التاريخية «الرماح الملونة»Las lanzas coloradas عام (1931) و«الطريق إلى إلدورادو» El camino de El Dorado عام (1947)، وفي جنس المقالة الأدبية ومنها «رسائل ورجال من فنزويلا»Letras y hombres de Venzuela عام (1948). ومن الآخرين الذين كتبوا في الحقبة الزمنية الروائية ذاتها لوسيلا بالاثيوس Lucila Palacios التي كانت ذات توجه اجتماعي، وميغيل أوتيرو سيلبا Miguel Otero Silva الذي وصف بدقة الواقع الاجتماعي الفنزويلي العنيف.

قامت ردة فعل ضد تيار الحداثة وممثليه فيما عرف بـ «جيل 1918» وكان آندريس إلوي بلانكو Andrés Eloy Blanco أشهر ممثلي هذا الجيل. أما أنطونيو آرايس Antonio Arraiz فقد كان أبرز ممثلي «جيل 1928» الطليعي، الذين تحلقوا حول دورية «بييرنِس» Viernes، وتبوأ مكاناً بارزاً بعد نجاح ديوانه «قاسٍ»Aspero عام (1924) وكان روائياً مهماً وكتب القصص القصيرة أيضاً.

ازدهر الشعر النسائي على يد شاعرات مثل إيدا غرامكو Ida Gramcko، وتحلق شعراء آخرون تأثروا ببابلو نيرودا Pablo Neruda حول دورية «سارديو» Sardio منهم رامون بالوماريس Ramón Palomares، وكان ماريانو بيكون - سالاس Mariano Picón-Salas من أبرز كتاب المقالة وبحّاثة وإنساني كتب «من الغزو حتى الاستقلال: ثلاثة قـرون من التاريـخ الثقافي الأمـريكي الإسباني»De la conquista a la independencia: Tres siglos de historia cultural hispano - americana عـام (1944)، وأيضاً أحد أعماله الأكثر أهمية «الأزمة والتغيير والتقاليد»Crisis, cambro, tradición عام (1952). ومن الوجوه الأدبية البارزة الأخرى في الأدب والفكر الفنزويلي يُعد خوان ليسكانو Juan Liscano ومؤلَّفه «القدر الإنساني»Humano destino عام (1950) الأهم في القرن العشرين. أما في النصف الثاني من القرن فقد برز كتاب في مجالات الرواية القصيرة والقصة القصيرة والمقالة مثل أدريانو گونثالث ليون Andriano González León الذي كتب حول العنف في المدن، وغستابو لويس كاريرا Gustavo Luis Carrera الذي كتب بحس اجتماعي، ولويس بريتو غارثيا Lois Britto Garcia الذي أسهم في التجديد اللغوي في روايته الطموحة «أبرابلابرا» Abrapalabra.[250]

اعتمد المسرح في فنزويلا على تقديم المسرح الأوربي والأمريكي بالدرجة الأولى، إلا أن عدداً من الأدباء كتبوا في هذا الجنس، منهم ميغيل أوتيرو سيلبا وأبرزهم گالييگوس الذي مهد الدرب لمسرح جدي في «معجزة العام» El Milagro del año عام (1915).

الموسيقى

الرياضة

المطبخ

أخرى

التعليم

الصحة

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب "Resultado Básico del XIV Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2011 (Mayo 2014)" (PDF). Ine.gov.ve. p. 29. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت "Venezuela". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Población de Venezuela en 2015" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Venezuela. 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Venezuela)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2023.