تاريخ الحياة

| جزء من سلسلة مقالات عن |

| علم الأحياء التطوري |

|---|

|

|

بوابة التطور تصنيف • مقالات متعلقة • كتب |

يتتبع تاريخ الحياة على الأرض History of life العمليات التي تطورت بواسطتها الكائنات الحية و الأحفورية، من أول ظهور للحياة إلى يومنا هذا. تشكلت الأرض منذ حوالي 4.5 مليار سنة (يُختصر بـ Ga، نسبة لـ gigaannum) وتشير الأدلة إلى أن الحياة نشأت قبل 3.7 Ga.[1][2][3](على الرغم من وجود بعض الأدلة على الحياة في وقت مبكر من 4.1 إلى 4.28 Ga، إلا أنها لا تزال مثيرة للجدل بسبب التكوين غير البيولوجي المحتمل للأحافير المزعومة.[1][4][5][6]) تشير أوجه التشابه بين جميع الأنواع المعروفة في الوقت الحاضر إلى أنها تباعدت خلال عملية التطور البشري عن سلف مشترك.[7] يعيش ما يقرب من 1 تريليون نوع حالياً على الأرض[8] تم تسمية 1.75-1.8 مليون منها فقط[9][10] و 1.8 مليون موثق في قاعدة بيانات مركزية.[11] تمثل هذه الأنواع الحية حالياً أقل من واحد بالمائة من جميع الأنواع التي عاشت على الأرض.[12][13]

−4500 — – −4000 — – −3500 — – −3000 — – −2500 — – −2000 — – −1500 — – −1000 — – −500 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

يأتي أول دليل على الحياة من بصمات الكربون الحيوية[2][3] and وأحفوريات ستروماتوليت [14]والتي اكتشفت في الصخور الثانوية وعمرها 3.7 مليار سنة من الصخور الآرية من غرب گرينلاند. في عام 2015، تم العثور على بقايا الحياة الحيوية في صخور عمرها 4.1 مليار سنة في أستراليا الغربية.[15][5]في مارس 2017، تم الإبلاغ عن دليل مفترض لاحتمال وجود أقدم أشكال الحياة على الأرض في شكل أحياء دقيقة متحجرة اكتشفت في منفس حرمائي في حزام نوڤجتك من كيبيك، كندا، التي ربما تكون قد عاشت منذ 4.28 مليار سنة، ولم يمض وقت طويل على تشكلت المحيطات قبل 4.4 مليار سنة، ولم يمض وقت طويل على تكوين الأرض منذ 4.54 مليار سنة.[16][17]

كانت الحصائر المجهرية للبكتيريا و العتائق المتعايشة هي الشكل السائد للحياة في العصر العتيق المبكر ويعتقد أن العديد من الخطوات الرئيسية في التطور المبكر قد حدثت في هذه البيئة.[18] أدى تطور التمثيل الضوئي، حوالي 3.5 Ga، في النهاية إلى تراكم نفاياته، الأكسجين، في الغلاف الجوي، مما أدى إلى حدث الأكسجة الكبير، الذي يبدأ حوالي 2.4 Ga.[19]يرجع أقدم دليل على حقيقيات النوى ( الخلايا المعقدة ذات العضيات) إلى 1.85 Ga،[20][21] وبينما ربما كانوا موجودين في وقت سابق، تسارع تنوعهم عندما بدأوا في استخدام الأكسجين في استقلاب. في وقت لاحق، بدأ ظهور حوالي 1.7 Ga، عضيات متعددة الخلايا، مع ظهور خلايا متمايزة تؤدي وظائف متخصصة.[22]التكاثر الجنسي، والذي يتضمن اندماج الخلايا التناسلية الذكرية والأنثوية (الأمشاج لتكوين الزيجوت في عملية تسمى الإخصاب ، على عكس [[اللاجنسي التكاثر ، الطريقة الأساسية لتكاثر الغالبية العظمى من الكائنات الحية الدقيقة ، بما في ذلك جميع حقيقيات النوى (التي تشمل الحيوانات و النباتات).[23]ومع ذلك، يظل أصل و تطور التكاثر الجنسي لغزاً لعلماء الأحياء على الرغم من أنه تطور بالفعل من سلف مشترك كان نوعاً وحيد الخلية حقيقي النواة.[24] ظهرت ثنائيات التناظر، الحيوانات التي لها جانب أيمن وأيسر يمثلان صورة معكوسة لبعضها البع ، ظهرت بحلول 555 Ma (منذ مليون سنة).[25]

تعود النباتات البرية متعددة الخلايا الشبيهة بالطحالب إلى ما يقرب من مليار سنة مضت،[26] على الرغم من أن الأدلة تشير إلى أن الأحياء الدقيقة شكلت أقدم النظم البيئية الأرضية، على الأقل 2.7 Ga.[27] يُعتقد أن الكائنات الحية الدقيقة مهدت الطريق لظهور النباتات البرية في العصر الاُردوڤيشي. كانت النباتات البرية ناجحة جداً لدرجة أنه يُعتقد أنها ساهمت في حدث الانقراض الديڤوني المتأخر.[28] (يبدو أن السلسلة السببية الطويلة تتضمن نجاح الشجرة المبكرة السرخس العتيق (1) جذبت مستويات CO2، مما أدى إلى التبريد العالمي وانخفاض مستويات سطح البحر، (2 ) عززت جذور الأركيوبتريس نمو التربة مما أدى إلى "زيادة" تجوية الصخور، وربما تسبب جريان المغذيات اللاحق في انتشار الطحالب مما أدى إلى حدث نقص الأكسجين الذي تسبب في موت الحياة البحرية. كانت الأنواع البحرية هي الضحايا الأساسيين لانقراض العصر الديڤوني المتأخر

ظهرت كائنات إدياكرا خلال فترة إدياكرا،[29] بينما نشأت الفقاريات، جنباً إلى جنب مع معظم الشعب الحديثة، حوالي خلال الانفجار الكامبري.[30]خلال فترة العصر الپرمي، سيطرت مندمجات الأقواس، بما في ذلك أسلاف الثدييات، على الأرض،[31]ولكن معظم هذه المجموعة انقرضت في الانقراض الجماعي الپرمي-الثلاثي .[32] أثناء التعافي من هذه الكارثة، أصبحت الأركوصورات أكثر الفقاريات البرية وفرة;[33]سيطرت إحدى مجموعات الأركوصورات، وهي الديناصورات، على الفترتين جوراسي و الطباشيري.[34] بعد انقراض العصر الطباشيري-الثلاثي قتل الديناصورات غير الطيرية،[35] تزايدت الثدييات بسرعة في الحجم والتنوع.[36]قد تكون حالات الانقراض الجماعي قد سرعت التطور من خلال توفير الفرص لمجموعات جديدة من الكائنات الحية للتنويع.[37]

أقرب تاريخ للأرض

History of Earth and its life | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

−4500 — – −4000 — – −3500 — – −3000 — – −2500 — – −2000 — – −1500 — – −1000 — – −500 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Scale: Ma (Millions of years) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

أقدم شظايا نيزكية عُثر عليها على الأرض عمرها حوالي 4.54 مليار سنة؛ هذا، مقترن بشكل أساسي بتأريخ رواسب الرصاص القديمة، قد وضع العمر المقدر للأرض في ذلك الوقت تقريباً.[40] للقمر نفس تركيبة القشرة الأرض ولكنها لا تحتوي على [[نواة كوكب | نواة] غنية بالحديد مثل الأرض. يعتقد العديد من العلماء أنه بعد حوالي 40 مليون سنة من تكوين الأرض، اصطدمت مع جسم بحجم المريخ، مما ألقى بمواد القشرة المدارية التي شكلت القمر. فرضية أخرى هي أن الأرض والقمر بدآ في الالتحام في نفس الوقت ولكن الأرض، التي تمتلك جاذبية أقوى بكثير من القمر المبكر، اجتذبت تقريباً كل جزيئات الحديد في المنطقة.[41]

حتى عام 2001، كان عمر أقدم الصخور الموجودة على الأرض حوالي 3.8 مليار سنة،[42][40]مما دفع العلماء لتقدير أن سطح الأرض كان ذائباً حتى ذلك الحين. وبناءً على ذلك، أطلقوا على هذا الجزء من تاريخ الأرض اسم الهاديان.[43]ومع ذلك، يشير تحليل زركونيوم المتكونة 4.4 Ga إلى أن قشرة الأرض قد تجمدت بعد حوالي 100 مليون سنة من تكوين الكوكب وأن الكوكب اكتسب بسرعة محيطات و الغلاف الجوي، والذي ربما كان قادراً على دعم الحياة.[44][45][46]

تشير الأدلة من القمر إلى أنه من 4 إلى 3.8 Ga عانت من الكارثة القمرية من الحطام المتبقي من تكوين النظام الشمسي، وكان من المفترض أن تتعرض الأرض لقصف أشد بسبب لجاذبيتها الأقوى.[43][47]على الرغم من عدم وجود دليل مباشر على الظروف على الأرض من 4 إلى 3.8 Ga، فلا يوجد سبب للاعتقاد بأن الأرض لم تتأثر أيضاً بهذا القصف الثقيل المتأخر.[48] قد يكون هذا الحدث قد جرد أي جو سابق ومحيطات؛ في هذه الحالة الغاز والمياه من المذنب قد تكون قد ساهمت في استبدالها، على الرغم من أن التفريغ الغازي من البراكين على الأرض كان سيوفر على الأقل نصف.[49] ومع ذلك ، إذا كانت الحياة الميكروبية تحت السطحية قد تطورت بحلول هذه المرحلة، لكانت قد نجت من القصف.[50]

أقدم الأدلة على الحياة على الأرض

كانت الكائنات الحية الأولى التي تم تحديدها دقيقة وعديمة الملامح نسبياً، وتبدو أحافيرها مثل قضبان صغيرة يصعب للغاية التمييز بينها وبين الهياكل التي تنشأ من خلال العمليات الفيزيائية اللاأحيائية. أقدم دليل لا جدال فيه على وجود الحياة على الأرض، والذي تم تفسيره على أنه بكتيريا متحجرة، يعود إلى 3 Ga.[51]تم تفسير الاكتشافات الأخرى في الصخور التي يعود تاريخها إلى حوالي 3.5 Ga على أنها بكتيريا،[52]مع أدلة الجيوكيميائية تظهر أيضاً وجود الحياة 3.8 Ga.[53]ومع ذلك، تم فحص هذه التحليلات عن كثب، وتم العثور على عمليات غير بيولوجية يمكن أن تنتج كل "بصمات الحياة" التي تم الإبلاغ عنها.[54][55] في حين أن هذا لا يثبت أن البنى التي تم العثور عليها لها أصل غير بيولوجي، فلا يمكن اعتبارها دليلاً واضحاً على وجود الحياة. تم تفسير التوقيعات الجيوكيميائية من الصخور المودعة 3.4 Ga كدليل على الحياة،[51][56]على الرغم من أن هذه التصريحات لم يتم فحصها بدقة من قبل النقاد.

تم العثور على أدلة على الكائنات الحية الدقيقة المتحجرة التي تعتبر من 3.77 مليار إلى 4.28 مليار سنة في حزام Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone في كيبيك، كندا ،[16]على الرغم من أن الأدلة تم الجدل فيها باعتبارها غير حاسمة.[57]

أصول الحياة على الأرض

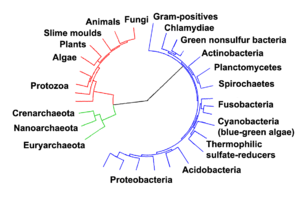

يعتقد علماء الأحياء أن جميع الكائنات الحية على الأرض يجب أن تشترك في أحدث سلف مشترك، لأنه سيكون من المستحيل فعلياً أن تكون سلالتان منفصلتان أو أكثر قد طورا بشكل مستقل العديد من الآليات الكيميائية الحيوية المعقدة المشتركة بين جميع الأحياء الكائنات الحية.[59][60]

البزوغ المستقل على الأرض

تعتمد الحياة على الأرض على الكربون و الماء. يوفر الكربون أطراً مستقرة للمواد الكيميائية المعقدة ويمكن استخلاصه بسهولة من البيئة، خاصةً من ثنائي أكسيد الكربون.[46] لا يوجد عنصر كيميائي آخر تتشابه خواصه بدرجة كافية مع خصائص الكربون ليتم تسميته بالتماثل؛ السليكون، العنصر الموجود أسفل الكربون مباشرة في الجدول الدوري، لا يشكل عدداً كبيراً جداً من الجزيئات المستقرة المعقدة، ولأن معظم مركباته غير قابلة للذوبان في الماء ولأن ثاني أكسيد السليكون مادة صلبة والصلبة الكاشطة على عكس ثنائي أكسيد الكربون في درجات الحرارة المرتبطة بالكائنات الحية، سيكون من الصعب استخلاص الكائنات الحية. تحتوي العناصر البورون و الفسفور على كيميائيات أكثر تعقيداً، ولكنها تعاني من قيود أخرى تتعلق بالكربون. الماء مذيب ممتاز وله خاصيتان مفيدتان أخريان: حقيقة أن عوامات الجليد تمكن الكائنات المائية من البقاء تحتها في الشتاء. وجزيئاتها سالبة كهربياً ونهايات موجبة، والتي تمكنها من تكوين نطاق أوسع من المركبات مقارنة بالمذيبات الأخرى. المذيبات الجيدة الأخرى، مثل الأمونيا، تكون سائلة فقط في درجات حرارة منخفضة لدرجة أن التفاعلات الكيميائية قد تكون بطيئة جداً لاستمرار الحياة، وتفتقر إلى مزايا الماء الأخرى.[61] الكائنات الحية القائمة على الكيمياء الحيوية البديلة قد تكون ،مع ذلك، ممكنة على الكواكب الأخرى.[62]

يركز البحث حول كيفية نشأة الحياة من المواد الكيميائية غير الحية على ثلاث نقاط انطلاق محتملة: نسخ ذاتي، قدرة الكائن الحي على إنتاج نسل مشابه جداً له؛ التمثيل الغذائي، وقدرتها على تغذية وإصلاح نفسها؛ و الأغشية الخلوية الخارجية، التي تسمح للأغذية بالدخول وإفراغ المنتجات، لكنها تستبعد المواد غير المرغوب فيها.[63]لا يزال أمام البحث عن التولد الذاتي طريق طويل، نظراً لأن المناهج النظرية و التجريبية بدأت للتو في الاتصال ببعضها البعض.[64][65]

التناسخ أولاً: عالَم الرنا RNA

حتى أبسط أعضاء نظام النطاقات الثلاث للحياة يستخدمون الحمض النووى الريبوزي منقوص الأكسجين لتسجيل "وصفاتهم" ومجموعة معقدة من حمض ريبي نووي و بروتين جزيئات "لقراءة" هذه التعليمات واستخدمها للنمو والصيانة والتكرار الذاتي. أدى اكتشاف أن بعض جزيئات الحمض النووي الريبي يمكن أن تحفز كلاً من تكاثرها وبناء البروتينات إلى فرضية وجود أشكال حياة سابقة تعتمد كلياً على الحمض النووي الريبي.[66]يمكن أن تكون هذه الريبوزيمات قد شكلت عالماً من الحمض النووي الريبي حيث يوجد أفراد ولكن لا توجد أنواع، لأن الطفرات و عمليات نقل الجينات الأفقي كان ستعني ذلك النسل في كل جيل من المحتمل جداً أن يكون لديهم جينومات مختلفة عن أولئك الذين بدأ آباؤهم معهم.[67]وقد تم استبدال الحمض النووي الريبي في وقت لاحق بالحمض النووي، وهو أكثر استقراراً وبالتالي يمكنه بناء جينومات أطول، مما يوسع نطاق القدرات التي يمكن أن يمتلكها كائن حي واحد.[67][68][69]حيث تظل الريبوزيمات هي المكونات الرئيسية للريبوسومات لمصانع بروتينات الخلايا الحديثة."[70]تشير الدلائل إلى أن جزيئات الحمض النووي الريبي تشكلت على الأرض قبل 4.17 Ga.[71]

على الرغم من أن جزيئات الحمض النووي الريبي قصيرة التكاثر الذاتي قد تم إنتاجها بشكل مصطنع في المختبرات،[72]وقد أثيرت شكوك حول ما إذا كان التوليف الطبيعي غير البيولوجي للحمض النووي الريبي ممكناً.[73]ربما تكونت "الريبوزيمات" الأقدم من حمض نووي أبسط مثل PNA، TNA أو GNA، الذي كان سيحل محله لاحقاً RNA.[74][75]

في عام 2003، تم اقتراح أن رواسب كبريتيد المعدن المسامي من شأنه أن يساعد في تخليق الحمض النووي الريبي عند حوالي 100 °C (212 °F) وضغوط قاع المحيط بالقرب من المنافس الحرارية المائية. بموجب هذه الفرضية، ستكون الأغشية الدهنية آخر مكونات الخلية الرئيسية التي تظهر، وحتى ذلك الحين، فإن الخلية الأولية ستقتصر على المسام.[76]

الأيض أولاً: عالم الحديد-الكبريت

أظهرت سلسلة من التجارب التي بدأت في عام 1997 أنه يمكن تحقيق المراحل المبكرة في تكوين البروتينات من المواد غير العضوية بما في ذلك أول أكسيد الكربون و كبريتيد الهيدروجين باستخدام كبريتيد الحديد و كبريتيد النيكل باعتبارها محفزات. تتطلب معظم الخطوات درجات حرارة تبلغ حوالي 100 °C (212 °F) وضغوط معتدلة، على الرغم من أن المرحلة الواحدة تتطلب 250 °C (482 °F) وضغطاً مكافئاً للضغط الموجود تحت 7 كيلومتر (4.3 mi) من الصخور. ومن ثم فقد اقترح أن تخليق البروتينات ذاتية الاستدامة يمكن أن يحدث بالقرب من الفتحات الحرارية المائية.[77]

الأغشية أولاً: عالم الدهون

لقد تم اقتراح أن "الفقاعات" مزدوجة الجدران من الدهون مثل تلك التي تشكل الأغشية الخارجية للخلايا قد تكون خطوة أولى أساسية.[78]أفادت التجارب التي تحاكي ظروف الأرض المبكرة بتكوين الدهون، ويمكن أن تتشكل تلقائياً جسيمات شحمية، "فقاعات" مزدوجة الجدران، ثم تتكاثر.[46]على الرغم من أنها ليست في جوهرها ناقلات معلومات مثل الأحماض النووية، فإنها تخضع الانتخاب الطبيعي من أجل طول العمر والتكاثر. قد تكون الأحماض النووية مثل الحمض النووي الريبي قد تكونت داخل الجسيمات الشحمية بسهولة أكبر مما تتشكل خارجها.[79]

فرضية الصلصال

الحمض النووي الريبوزي معقد وهناك شكوك حول ما إذا كان يمكن إنتاجه بطريقة غير بيولوجية في البرية.[73] بعض الصلصال، ولا سيما مونتموريلونيت، لها خصائص تجعلها مسرعات معقولة لظهور عالم الرنا: فهي تنمو بالتكاثر الذاتي لنمطها المتبلور؛ يخضعون لنظير من الانتقاء الطبيعي، لأن "الأنواع" الطينية التي تنمو بشكل أسرع في بيئة معينة تصبح مهيمنة بسرعة؛ ويمكنهم تحفيز تكوين جزيئات الحمض النووي الريبي.[80] على الرغم من أن هذه الفكرة لم تصبح إجماعاً علمياً، إلا أنها لا تزال تحظى بدعم نشط.[81]

أفادت الأبحاث التي أجريت في عام 2003 أن المونتموريلونايت يمكنه أيضاً تسريع تحويل الأحماض الدهنية إلى "فقاعات"، وأن "الفقاعات" يمكن أن تغلف الحمض النووي الريبي المرتبط بالطين. يمكن أن تنمو هذه "الفقاعات" بعد ذلك عن طريق امتصاص الدهون الإضافية ثم الانقسام. قد يكون تكوين الخلايا الأقدم قد ساعد في عمليات مماثلة.[82]

تقدم فرضية مماثلة الطين الغني بالحديد ذاتي التكاثر باعتباره أسلاف النيوكليوتيدات والدهون و الأحماض الأمينية.[83]

الحياة "من بذرة" من مكان آخر

لا تشرح فرضية النطفة الفضائية كيف نشأت الحياة في المقام الأول، ولكنها تفحص ببساطة إمكانية أن تأتي من مكان آخر غير الأرض. تعود فكرة أن الحياة على الأرض كانت "مشتقة" من مكان آخر في الكون إلى الفيلسوف اليوناني أناكسيماندر في القرن السادس قبل الميلاد.[84]في القرن العشرين تم اقتراحه من قبل الكيميائي الفيزيائي سڤانت أرنيوس،[85] بواسطة الفلكيان فريد هويل و تشاندرا ويكراماسنگ،[86]وبواسطة عالم الأحياء الجزيئي فرانسيس كريك والكيميائي لزلي أورگل.[87]

هناك ثلاثة نصوص رئيسية من فرضية الحياة "من بذرة" من مكان آخر: في نظامنا الشمسي عبر شظايا طرقت في الفضاء بتأثير نيزك كبير، وفي هذه الحالة تكون المصادر الأكثر مصداقية هي المريخ[88] و الزهرة;[89]بواسطة الزوار الأجانب، ربما نتيجة التلوث العرضي بواسطة الكائنات الحية الدقيقة التي جلبوها معهم;[87]ومن خارج المجموعة الشمسية ولكن بالوسائل الطبيعية.[85][88]

أثبتت التجارب في مدار أرضي منخفض، مثل EXOSTACK، أن بعض أبواغ الكائنات الحية الدقيقة يمكن أن تنجو من صدمة قذفها إلى الفضاء ويمكن للبعض أن ينجو من التعرض لإشعاع الفضاء الخارجي من أجل 5.7 سنوات على الأقل.[90][91] ينقسم العلماء حول احتمالية نشوء الحياة بشكل مستقل على المريخ،[92] أو على كواكب أخرى في مجرتنا.[88]

الوقع البيئي والتطوري للبسائط الجرثومية

الحصائر الميكروبية عبارة عن مستعمرات متعددة الطبقات ومتعددة الأنواع من البكتيريا والكائنات الأخرى التي يبلغ سمكها عموماً بضعة ملليمترات فقط، ولكنها لا تزال تحتوي على مجموعة واسعة من البيئات الكيميائية، كل منها يفضل مجموعة مختلفة من الكائنات الحية الدقيقة.[93] إلى حد ما، تشكل كل حصيرة سلسلة غذائية خاصة بها، حيث تعمل المنتجات الثانوية لكل مجموعة من الكائنات الحية الدقيقة عموماً "كغذاء" للمجموعات المجاورة.[94]

ستروماتوليت هي أعمدة قصيرة مبنية ككائنات دقيقة في الحصير تهاجر ببطء إلى أعلى لتجنب اختناقها بالرواسب المترسبة عليها بواسطة الماء.[93] كان هناك نقاش حاد حول صحة الحفريات المزعومة من قبل 3 Ga،[95]مع نقاد يجادلون بأن ما يسمى بالستروماتوليت يمكن أن تكون قد تشكلت من خلال عمليات غير بيولوجية.[54] في عام 2006، تم الإبلاغ عن اكتشاف آخر للستروماتوليت من نفس الجزء من أستراليا مثل الأجزاء السابقة، في الصخور المؤرخة بـ 3.5 Ga.[96]

في الحصائر الحديثة تحت الماء، غالباً ما تتكون الطبقة العليا من التمثيل الضوئي من الطحالب الزرقاء التي تخلق بيئة غنية بالأكسجين، في حين أن الطبقة السفلية خالية من الأكسجين وغالباً ما يهيمن عليها كبريتيد الهيدروجين المنبعث من الكائنات الحية التي تعيش هناك.[94]تشير التقديرات إلى أن ظهور التمثيل الضوئي للأكسجين بواسطة البكتيريا في الحصائر أدى إلى زيادة الإنتاجية البيولوجية بعامل يتراوح بين 100 و 1000. العامل المختزل المستخدم في عملية التمثيل الضوئي للأكسجين هو الماء، وهو أكثر وفرة بكثير من عوامل الاختزال المنتجة جيولوجياً والتي تتطلبها عملية التمثيل الضوئي غير الأكسجينية السابقة.[97] من هذه النقطة فصاعداً، أنتجت الحياة نفسها قدراً كبيراً من الموارد التي تحتاجها أكثر من العمليات الجيوكيميائية.[98] الأكسجين سام للكائنات التي لا تتكيف معها، ولكنه يزيد بشكل كبير من كفاءة التمثيل الغذائي للكائنات الحية المتكيفة مع الأكسجين.[99][100] أصبح الأكسجين مكوناً مهماً للغلاف الجوي للأرض حوالي 2.4 Ga.[101] على الرغم من أن حقيقيات النوى ربما كانت موجودة قبل ذلك بكثير،[102][103] كان أكسجة الغلاف الجوي شرطاً أساسياً لتطور الخلايا حقيقية النواة الأكثر تعقيداً، والتي تُبنى منها جميع الكائنات متعددة الخلايا.[104] كان من الممكن أن تتحرك الحدود بين الطبقات الغنية بالأكسجين والخالية من الأكسجين في الحصائر الميكروبية لأعلى عندما تتوقف عملية التمثيل الضوئي بين عشية وضحاها، ثم تنخفض إلى أسفل حيث يتم استئنافها في اليوم التالي. كان من الممكن أن يخلق هذا ضغط الانتقاء للكائنات الموجودة في هذه المنطقة الوسيطة لاكتساب القدرة على تحمل الأكسجين ثم استخدامه، ربما عن طريق التعايش الداخلي، حيث يعيش كائن حي داخل آخر وكلاهما لهم الاستفادة من ارتباطها.[18]

تحتوي البكتيريا الزرقاء على "مجموعة أدوات" البيوكيميائية الأكثر اكتمالا من بين جميع الكائنات الحية المكونة للحصيرة. ومن ثم فهي الأكثر اكتفاءً ذاتياً من كائنات الحصائر وتم تكيفها جيداً لتضرب بمفردها كحصائر عائمة وكأول العوالق النباتية، مما يوفر الأساس لمعظم سلاسل الغذاء البحرية.[18]

تنوع حقيقيات النوى

| Eukarya |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

الكروماتين والنواة ونظام الغشاء الداخلي والمتقدرات

قد تكون حقيقيات النوى موجودة قبل فترة طويلة من أكسجة الغلاف الجوي،[102]لكن معظم حقيقيات النوى الحديثة تتطلب الأكسجين، والذي تستخدمه المتقدرات لتغذية إنتاج ATP، وهو مصدر الطاقة الداخلي لجميع الخلايا المعروفة.[104] في السبعينيات من القرن الماضي، تم اقتراح ذلك، وبعد الكثير من الجدل، تم قبول فكرة ظهور حقيقيات النوى كنتيجة لسلسلة من التعايش الداخلي بين بدائيات النوى. على سبيل المثال: غزا مفترس كائن حي دقيق بدائيات نوى كبيرة، ربما العتائق، ولكن تم تحييد الهجوم، وأقام المهاجم وتطور إلى أول متقدرة؛ حاول أحد هؤلاء الكيميرا لاحقاً ابتلاع بكتيريا زرقاء ضوئية، لكن الضحية نجت داخل المهاجم وأصبحت التركيبة الجديدة هي سلف النباتات؛ وما إلى ذلك وهلم جرا. بعد بدء كل تعايش داخلي، كان الشركاء قد أزالوا التكرار غير المنتج للوظائف الجينية من خلال إعادة ترتيب الجينومات الخاصة بهم، وهي عملية تنطوي في بعض الأحيان على نقل الجينات بينهم.[107][108][109] تقترح فرضية أخرى أن المتقدرات كانت في الأصل متعايشة داخلياً بالـ كبريت - أو هيدروجين -، وأصبحت مستهلكة للأكسجين فيما بعد.[110] من ناحية أخرى، ربما كانت المتقدرات جزءاً من المعدات الأصلية لحقيقيات النوى.[111]

هناك جدل حول وقت ظهور حقيقيات النوى لأول مرة: قد يشير وجود ستيرانات في [[طفل صفحي]|الصخور الزيتية] الأسترالية إلى أن حقيقيات النوى كانت موجودة 2.7 Ga;[103] ومع ذلك، خلص تحليل في عام 2008 إلى أن هذه المواد الكيميائية اخترقت الصخور التي تقل عن 2.2 Ga ولا تثبت شيئاً عن أصول حقيقيات النوى.[112]تم الإبلاغ عن أحفورات طحالب گرپانيا في صخور عمرها 1.85 مليار سنة (يعود تاريخها في الأصل إلى 2.1 Ga ولكن تم تنقيحها لاحقاً[21]), ويشير إلى أن حقيقيات النوى مع العضيات قد تطورت بالفعل.[113]تم العثور على مجموعة متنوعة من الطحالب الأحفورية في الصخور المؤرخة بين 1.5 و 1.4 Ga.[114] يرجع تاريخ أقدم الحفريات المعروفة لـ الفطريات إلى 1.43 Ga.[115]

الصانعات

الصانعات، الطبقة الفائقة من العضيات الخلوية التي تعتبر البلاستيدات الخضراء هي أفضل نموذج معروف، يُعتقد أنها نشأت من التعايش الداخلي البكتيريا الزرقاء. تطور التعايش حول 1.5 Ga ومكّن حقيقيات النوى من تنفيذ التمثيل الضوئي للأكسجين.[104]ثلاث سلالات تطورية للبلاستيدات الضوئيةظهرت منذ ذلك الحين حيث تمت تسمية البلاستيدات بشكل مختلف: البلاستيدات الخضراء في الطحالب الخضراء والنباتات و رودوبلاست في الطحالب الحمراء و الطحالب الزرقاء في النباتات الزرق.[116]

التكاثر الجنسي والعضيات عديدة الخلايا

تطور التكاثر الجنسي

الخصائص المميزة لـ التكاثر الجنسي في حقيقيات النوى هي الانقسام الاختزالي و الإخصاب. هناك الكثير من إعادة التركيب الجيني في هذا النوع من التكاثر، حيث يتلقى الأبناء 50٪ من جيناتهم من كل والد،[117] على النقيض من التكاثر اللاجنسي، حيث لا يوجد إعادة تركيب. تتبادل البكتيريا أيضاً الحمض النووي عن طريق الاقتران البكتيري ، والتي تشمل فوائدها مقاومة المضادات الحيوية و السموم الأخرى، والقدرة على استخدام المستقلبات الجديدة.[118] ومع ذلك، فإن الاقتران ليس وسيلة للتكاثر، ولا يقتصر على أفراد من نفس النوع - هناك حالات تنقل فيها البكتيريا الحمض النووي إلى النباتات والحيوانات.[119]

من ناحية أخرى، من الواضح أن التحول البكتيري هو تكيف لنقل الحمض النووي بين البكتيريا من نفس النوع. التحول البكتيري هو عملية معقدة تنطوي على منتجات العديد من الجينات البكتيرية ويمكن اعتبارها شكلاً من أشكال الجنس البكتيري.[120][121] تحدث هذه العملية بشكل طبيعي في ما لا يقل عن 67 نوعاً من بدائيات النوى (في سبع شعب مختلفة).[122] قد يكون التكاثر الجنسي في حقيقيات النوى قد تطور من التحول البكتيري.[123]

إن مساوئ التكاثر الجنسي معروفة جيداً: قد يؤدي التعديل الوراثي لإعادة التركيب إلى تفتيت التوليفات المواتية من الجينات؛ وبما أن الذكور لا يزيدون بشكل مباشر من عدد الأبناء في الجيل التالي، فإن السكان اللاجنسيين يمكن أن يتكاثروا ويخرجوا في أقل من 50 جيلاً من السكان الجنسيين المتكافئين من جميع النواحي الأخرى.[117]ومع ذلك، فإن الغالبية العظمى من الحيوانات والنباتات والفطريات و الكائنات الأولية تتكاثر جنسياً. هناك دليل قوي على أن التكاثر الجنسي نشأ في وقت مبكر من تاريخ حقيقيات النوى وأن الجينات التي تتحكم فيه لم تتغير إلا قليلاً منذ ذلك الحين.[124]كيف تطور التكاثر الجنسي وكيف نجا هو لغز لم يحل.[125]

تقترح فرضية الملكة الحمراء أن التكاثر الجنسي يوفر الحماية ضد الطفيليات، لأنه يسهل على الطفيليات تطوير وسائل للتغلب على دفاعات الاستنساخ المتطابقة وراثياً مقارنة بالدفاعات الجنسية الأنواع التي تقدم أهدافاً متحركة، وهناك بعض الأدلة التجريبية على ذلك. ومع ذلك، لا يزال هناك شك حول ما إذا كان من شأنه أن يفسر بقاء الأنواع الجنسية في حالة وجود العديد من الأنواع المستنسخة المماثلة، حيث أن أحد الحيوانات المستنسخة قد ينجو من هجمات الطفيليات لفترة كافية لتتفوق على الأنواع الجنسية.[117] علاوة على ذلك، خلافاً لتوقعات فرضية الملكة الحمراء، كاثرين أ.هانلي وآخرون. وجد أن انتشار ووفرة ومتوسط كثافة العث كان أعلى بشكل ملحوظ في الأبراص مقارنة باللاجنسيين الذين يتشاركون نفس الموطن.[127] بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فشل عالم الأحياء ماثيو پاركر، بعد مراجعة العديد من الدراسات الجينية حول مقاومة الأمراض النباتية، في العثور على مثال واحد يتوافق مع مفهوم أن مسببات الأمراض هي العامل الانتقائي الأساسي المسؤول عن التكاثر الجنسي في المضيف..[128]

يفترض ألكسي كوندرشوڤ "فرضية الطفرة الحتمية" (DMH) أن كل كائن حي لديه أكثر من طفرة ضارة وأن التأثيرات المجمعة لهذه الطفرات أكثر ضررًا من مجموع الضرر الذي تسببه كل طفرة فردية. إذا كان الأمر كذلك ، فإن إعادة التركيب الجنسي للجينات سيقلل من الضرر الذي تلحقه الطفرات السيئة بالنسل وفي نفس الوقت يقضي على بعض الطفرات السيئة من تجمع جيني عن طريق عزلها في الأفراد الذين يهلكون بسرعة لأن لديهم عدداً أعلى من المتوسط من الطفرات السيئة. ومع ذلك، تشير الدلائل إلى أن افتراضات DMH مهتزة لأن العديد من الأنواع لديها في المتوسط أقل من طفرة ضارة واحدة لكل فرد ولا يُظهر أي نوع تم فحصه دليلًا على التآزر بين الطفرات الضارة.[117]

تتسبب الطبيعة العشوائية لإعادة التركيب في اختلاف الوفرة النسبية للسمات البديلة من جيل إلى آخر. هذا الانحراف الوراثي غير كافٍ بحد ذاته لجعل التكاثر الجنسي مفيداً، لكن مزيجاً من الانحراف الوراثي والانتقاء الطبيعي قد يكون كافياً. عندما تنتج الصدفة مجموعات من السمات الجيدة، فإن الانتقاء الطبيعي يعطي ميزة كبيرة للسلالات التي ترتبط فيها هذه الصفات جينياً. من ناحية أخرى، يتم تحييد فوائد السمات الجيدة إذا ظهرت جنباً إلى جنب مع السمات السيئة. يعطي إعادة التركيب الجنسي الصفات الجيدة فرصاً للارتباط بسمات جيدة أخرى، وتشير النماذج الرياضية إلى أن هذا قد يكون أكثر من كافٍ لتعويض مساوئ التكاثر الجنسي.[125] يتم أيضاً فحص مجموعات أخرى من الفرضيات غير الملائمة من تلقاء نفسها.[117]

لا تزال الوظيفة التكيفية للجنس اليوم قضية رئيسية لم يتم حلها في علم الأحياء. تمت مراجعة النماذج المتنافسة لشرح الوظيفة التكيفية للجنس من قبل جون إيه بيردسيل و كرستوفر ولز.[129] تعتمد الفرضيات التي نوقشت أعلاه على الآثار المفيدة المحتملة للتنوع الجيني العشوائي الناتج عن إعادة التركيب الجيني. وجهة نظر بديلة هي أن الجنس نشأ واستمر كعملية لإصلاح تلف الحمض النووي، وأن التباين الجيني الناتج هو منتج ثانوي مفيد في بعض الأحيان.[123][130]

تعدد الخلايا

أبسط تعريفات "متعددة الخلايا"، على سبيل المثال "وجود خلايا متعددة"، يمكن أن تشمل مستعمرة البكتيريا الزرقاء مثل نوستك. حتى التعريف التقني مثل "وجود نفس الجينوم ولكن أنواع مختلفة من الخلايا" سيظل يتضمن بعض الأجناس من الطحالب الخضراء ڤولڤوكس، التي تحتوي على خلايا متخصصة في التكاثر.[131]تطورت تعددية الخلايا بشكل مستقل في كائنات متنوعة مثل الإسفنجيات والحيوانات الأخرى والفطريات والنباتات و الطحالب البنية والبكتيريا الزرقاء و العفن الغروي و الجراثيم المخاطية.[21][132] من أجل الإيجاز، تركز هذه المقالة على الكائنات الحية التي تُظهر أكبر تخصص للخلايا وأنواع مختلفة من الخلايا، على الرغم من أن هذا النهج في تطور التعقيد البيولوجي يمكن اعتباره " محور الإنسان إلى حد ما."[22]

قد تتضمن المزايا الأولية لتعدد الخلايا ما يلي: مشاركة أكثر فعالية للعناصر الغذائية التي يتم هضمها خارج الخلية،[134]زيادة المقاومة للحيوانات المفترسة، التي يهاجم الكثير منها بالابتلاع؛ القدرة على مقاومة التيارات من خلال التعلق بسطح ثابت؛ القدرة على الوصول لأعلى لتغذية المرشح أو الحصول على ضوء الشمس من أجل التمثيل الضوئي;[135] القدرة على خلق بيئة داخلية توفر الحماية ضد البيئة الخارجية;[22] وحتى الفرصة لمجموعة من الخلايا للتصرف "بذكاء" من خلال مشاركة المعلومات.[133]كانت هذه الميزات ستوفر أيضاً فرصاً للكائنات الأخرى للتنويع، من خلال إنشاء بيئات أكثر تنوعاً مما يمكن للحصائر الميكروبية المسطحة.[135]

تعد تعدد الخلايا مع الخلايا المتمايزة مفيدة للكائن ككل ولكنه غير مؤاتٍ من وجهة نظر الخلايا الفردية، والتي يفقد معظمها فرصة إعادة إنتاج نفسها. في كائن حي متعدد الخلايا لاجنسي، قد تتولى الخلايا المارقة التي تحتفظ بالقدرة على التكاثر، وتقلل من الكائن الحي إلى كتلة من الخلايا غير المتمايزة. يقضي التكاثر الجنسي على مثل هذه الخلايا المارقة من الجيل التالي، وبالتالي يبدو أنه شرط أساسي لتعدد الخلايا المعقدة.[135]

تشير الأدلة المتاحة إلى أن حقيقيات النوى تطورت في وقت مبكر جداً ولكنها ظلت غير واضحة حتى التنويع السريع في حوالي 1 Ga والاحترام الوحيد الذي تتفوق فيه حقيقيات النوى بوضوح على البكتيريا والعتائق هو قدرتها على مجموعة متنوعة من الأشكال، ومكّن التكاثر الجنسي حقيقيات النوى من استغلال تلك الميزة من خلال الإنتاج الكائنات الحية ذات الخلايا المتعددة التي تختلف في الشكل والوظيفة.[135]

من خلال مقارنة تكوين عائلات عامل النسخ وعناصر الشبكة التنظيمية بين الكائنات أحادية الخلية والكائنات متعددة الخلايا، وجد العلماء أن هناك العديد من عائلات عوامل النسخ الجديدة وثلاثة أنواع جديدة من أشكال الشبكة التنظيمية في الكائنات متعددة الخلايا، وعوامل النسخ العائلية الجديدة موصولة بشكل تفضيلي في هذه الزخارف الشبكية الجديدة التي تعتبر ضرورية للتطور متعدد الخلايا. تقترح هذه النتائج آلية معقولة لمساهمة عوامل النسخ للعائلة الجديدة وعناصر الشبكة الجديدة في أصل الكائنات متعددة الخلايا على المستوى التنظيمي النسخي.[136]

الأدلة الأحفورية

إن أحافير الكائنات الحية الفرنسيڤيلية، المؤرخة بـ 2.1 Ga، هي أقدم الكائنات الأحفورية المعروفة التي من الواضح أنها متعددة الخلايا.[39] They may have had differentiated cells.[137] يبدو أن حفرية أخرى مبكرة متعددة الخلايا، "Qingshania"، والتي يرجع تاريخها إلى 1.7 Ga، تتكون من خلايا متطابقة تقريباً. الطحالب الحمراء المسماة "بانجيومورفا"، والتي يرجع تاريخها إلى 1.2 Ga، هي أقدم كائن حي معروف له بالتأكيد خلايا متمايزة ومتخصصة، وهو أيضاً أقدم كائن حي معروف عن التكاثر الجنسي.[135] يبدو أن الحفريات التي يبلغ عمرها 1.43 مليار عام والتي تم تفسيرها على أنها فطريات كانت متعددة الخلايا ذات خلايا متباينة.[115] "سلسلة الخرز" الكائن الحي هورودسكيا، التي تم العثور عليها في الصخور المؤرخة من 1.5 Ga إلى 900 Ma، ربما كانت ميتازواناً مبكراً;[21]ومع ذلك، فقد تم تفسيرها أيضاً على أنها منخربات.[126]

بزوغ الحيوانات

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

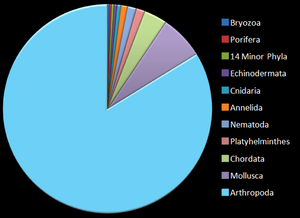

Animals are multicellular eukaryotes,[note 1] and are distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking cell walls.[139] All animals are motile,[140] if only at certain life stages. All animals except sponges have bodies differentiated into separate tissues, including muscles, which move parts of the animal by contracting, and nerve tissue, which transmits and processes signals.[141] In November 2019, researchers reported the discovery of Caveasphaera, a multicellular organism found in 609-million-year-old rocks, that is not easily defined as an animal or non-animal, which may be related to one of the earliest instances of animal evolution.[142][143] Fossil studies of Caveasphaera have suggested that animal-like embryonic development arose much earlier than the oldest clearly defined animal fossils.[142] and may be consistent with studies suggesting that animal evolution may have begun about 750 million years ago.[143][144]

Nonetheless, the earliest widely accepted animal fossils are the rather modern-looking cnidarians (the group that includes jellyfish, sea anemones and Hydra), possibly from around , although fossils from the Doushantuo Formation can only be dated approximately. Their presence implies that the cnidarian and bilaterian lineages had already diverged.[145]

The Ediacara biota, which flourished for the last 40 million years before the start of the Cambrian,[146] were the first animals more than a very few centimetres long. Many were flat and had a "quilted" appearance, and seemed so strange that there was a proposal to classify them as a separate kingdom, Vendozoa.[147] Others, however, have been interpreted as early molluscs (Kimberella[148][149]), echinoderms (Arkarua[150]), and arthropods (Spriggina,[151] Parvancorina[152]). There is still debate about the classification of these specimens, mainly because the diagnostic features which allow taxonomists to classify more recent organisms, such as similarities to living organisms, are generally absent in the Ediacarans. However, there seems little doubt that Kimberella was at least a triploblastic bilaterian animal, in other words, an animal significantly more complex than the cnidarians.[153]

The small shelly fauna are a very mixed collection of fossils found between the Late Ediacaran and Middle Cambrian periods. The earliest, Cloudina, shows signs of successful defense against predation and may indicate the start of an evolutionary arms race. Some tiny Early Cambrian shells almost certainly belonged to molluscs, while the owners of some "armor plates," Halkieria and Microdictyon, were eventually identified when more complete specimens were found in Cambrian lagerstätten that preserved soft-bodied animals.[154]

In the 1970s there was already a debate about whether the emergence of the modern phyla was "explosive" or gradual but hidden by the shortage of Precambrian animal fossils.[154] A re-analysis of fossils from the Burgess Shale lagerstätte increased interest in the issue when it revealed animals, such as Opabinia, which did not fit into any known phylum. At the time these were interpreted as evidence that the modern phyla had evolved very rapidly in the Cambrian explosion and that the Burgess Shale's "weird wonders" showed that the Early Cambrian was a uniquely experimental period of animal evolution.[156] Later discoveries of similar animals and the development of new theoretical approaches led to the conclusion that many of the "weird wonders" were evolutionary "aunts" or "cousins" of modern groups[157]—for example that Opabinia was a member of the lobopods, a group which includes the ancestors of the arthropods, and that it may have been closely related to the modern tardigrades.[158] Nevertheless, there is still much debate about whether the Cambrian explosion was really explosive and, if so, how and why it happened and why it appears unique in the history of animals.[159]

ثانويات الفم وأول الفقاريات

Most of the animals at the heart of the Cambrian explosion debate are protostomes, one of the two main groups of complex animals. The other major group, the deuterostomes, contains invertebrates such as starfish and sea urchins (echinoderms), as well as chordates (see below). Many echinoderms have hard calcite "shells," which are fairly common from the Early Cambrian small shelly fauna onwards.[154] Other deuterostome groups are soft-bodied, and most of the significant Cambrian deuterostome fossils come from the Chengjiang fauna, a lagerstätte in China.[161] The chordates are another major deuterostome group: animals with a distinct dorsal nerve cord. Chordates include soft-bodied invertebrates such as tunicates as well as vertebrates—animals with a backbone. While tunicate fossils predate the Cambrian explosion,[162] the Chengjiang fossils Haikouichthys and Myllokunmingia appear to be true vertebrates,[30] and Haikouichthys had distinct vertebrae, which may have been slightly mineralized.[163] Vertebrates with jaws, such as the acanthodians, first appeared in the Late Ordovician.[164]

استعمار الأرض

Adaptation to life on land is a major challenge: all land organisms need to avoid drying-out and all those above microscopic size must create special structures to withstand gravity; respiration and gas exchange systems have to change; reproductive systems cannot depend on water to carry eggs and sperm towards each other.[165][166][167] Although the earliest good evidence of land plants and animals dates back to the Ordovician period (), and a number of microorganism lineages made it onto land much earlier,[168][169] modern land ecosystems only appeared in the Late Devonian, about .[170] In May 2017, evidence of the earliest known life on land may have been found in 3.48-billion-year-old geyserite and other related mineral deposits (often found around hot springs and geysers) uncovered in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia.[171][172] In July 2018, scientists reported that the earliest life on land may have been bacteria living on land 3.22 billion years ago.[173] In May 2019, scientists reported the discovery of a fossilized fungus, named Ourasphaira giraldae, in the Canadian Arctic, that may have grown on land a billion years ago, well before plants were living on land.[174][175][176]

تطور مانعات الأكسدة الأرضية

Oxygen is a potent oxidant whose accumulation in terrestrial atmosphere resulted from the development of photosynthesis over 3 Ga, in cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), which were the most primitive oxygenic photosynthetic organisms. Brown algae accumulate inorganic mineral antioxidants such as rubidium, vanadium, zinc, iron, copper, molybdenum, selenium and iodine which is concentrated more than 30,000 times the concentration of this element in seawater. Protective endogenous antioxidant enzymes and exogenous dietary antioxidants helped to prevent oxidative damage. Most marine mineral antioxidants act in the cells as essential trace elements in redox and antioxidant metalloenzymes.[citation needed]

When plants and animals began to enter rivers and land about 500 Ma, environmental deficiency of these marine mineral antioxidants was a challenge to the evolution of terrestrial life.[177][178] Terrestrial plants slowly optimized the production of “new” endogenous antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, polyphenols, flavonoids, tocopherols, etc. A few of these appeared more recently, in last 200–50 Ma, in fruits and flowers of angiosperm plants.[citation needed]

In fact, angiosperms (the dominant type of plant today) and most of their antioxidant pigments evolved during the Late Jurassic period. Plants employ antioxidants to defend their structures against reactive oxygen species produced during photosynthesis. Animals are exposed to the same oxidants, and they have evolved endogenous enzymatic antioxidant systems.[179] Iodine in the form of the iodide ion I- is the most primitive and abundant electron-rich essential element in the diet of marine and terrestrial organisms, and iodide acts as an electron donor and has this ancestral antioxidant function in all iodide-concentrating cells from primitive marine algae to more recent terrestrial vertebrates.[180]

تطور التربة

Before the colonization of land, soil, a combination of mineral particles and decomposed organic matter, did not exist. Land surfaces would have been either bare rock or unstable sand produced by weathering. Water and any nutrients in it would have drained away very quickly.[170] In the Sub-Cambrian peneplain in Sweden for example maximum depth of kaolinitization by Neoproterozoic weathering is about 5 m, in contrast nearby kaolin deposits developed in the Mesozoic are much thicker.[181] It has been argued that in the late Neoproterozoic sheet wash was a dominant process of erosion of surface material due to the lack of plants on land.[182]

Films of cyanobacteria, which are not plants but use the same photosynthesis mechanisms, have been found in modern deserts, and only in areas that are unsuitable for vascular plants. This suggests that microbial mats may have been the first organisms to colonize dry land, possibly in the Precambrian. Mat-forming cyanobacteria could have gradually evolved resistance to desiccation as they spread from the seas to intertidal zones and then to land.[170] Lichens, which are symbiotic combinations of a fungus (almost always an ascomycete) and one or more photosynthesizers (green algae or cyanobacteria),[183] are also important colonizers of lifeless environments,[170] and their ability to break down rocks contributes to soil formation in situations where plants cannot survive.[183] The earliest known ascomycete fossils date from in the Silurian.[170]

Soil formation would have been very slow until the appearance of burrowing animals, which mix the mineral and organic components of soil and whose feces are a major source of the organic components.[170] Burrows have been found in Ordovician sediments, and are attributed to annelids ("worms") or arthropods.[170][184]

النباتات وأزمة الغابات الديڤونية

In aquatic algae, almost all cells are capable of photosynthesis and are nearly independent. Life on land required plants to become internally more complex and specialized: photosynthesis was most efficient at the top; roots were required in order to extract water from the ground; the parts in between became supports and transport systems for water and nutrients.[165][185]

Spores of land plants, possibly rather like liverworts, have been found in Middle Ordovician rocks dated to about . In Middle Silurian rocks , there are fossils of actual plants including clubmosses such as Baragwanathia; most were under 10 سنتيمتر (3.9 in) high, and some appear closely related to vascular plants, the group that includes trees.[185]

By the Late Devonian , trees such as Archaeopteris were so abundant that they changed river systems from mostly braided to mostly meandering, because their roots bound the soil firmly.[186] In fact, they caused the "Late Devonian wood crisis"[187] because:

- They removed more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, reducing the greenhouse effect and thus causing an ice age in the Carboniferous period.[28] In later ecosystems the carbon dioxide "locked up" in wood is returned to the atmosphere by decomposition of dead wood. However, the earliest fossil evidence of fungi that can decompose wood also comes from the Late Devonian.[188]

- The increasing depth of plants' roots led to more washing of nutrients into rivers and seas by rain. This caused algal blooms whose high consumption of oxygen caused anoxic events in deeper waters, increasing the extinction rate among deep-water animals.[28]

الفقاريات البرية

Animals had to change their feeding and excretory systems, and most land animals developed internal fertilization of their eggs.[167] The difference in refractive index between water and air required changes in their eyes. On the other hand, in some ways movement and breathing became easier, and the better transmission of high-frequency sounds in air encouraged the development of hearing.[166]

The oldest known air-breathing animal is Pneumodesmus, an archipolypodan millipede from the Middle Silurian, about .[189][190] Its air-breathing, terrestrial nature is evidenced by the presence of spiracles, the openings to tracheal systems.[191] However, some earlier trace fossils from the Cambrian-Ordovician boundary about are interpreted as the tracks of large amphibious arthropods on coastal sand dunes, and may have been made by euthycarcinoids,[192] which are thought to be evolutionary "aunts" of myriapods.[193] Other trace fossils from the Late Ordovician a little over probably represent land invertebrates, and there is clear evidence of numerous arthropods on coasts and alluvial plains shortly before the Silurian-Devonian boundary, about , including signs that some arthropods ate plants.[194] Arthropods were well pre-adapted to colonise land, because their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water.[167][195]

The fossil record of other major invertebrate groups on land is poor: none at all for non-parasitic flatworms, nematodes or nemerteans; some parasitic nematodes have been fossilized in amber; annelid worm fossils are known from the Carboniferous, but they may still have been aquatic animals; the earliest fossils of gastropods on land date from the Late Carboniferous, and this group may have had to wait until leaf litter became abundant enough to provide the moist conditions they need.[166]

The earliest confirmed fossils of flying insects date from the Late Carboniferous, but it is thought that insects developed the ability to fly in the Early Carboniferous or even Late Devonian. This gave them a wider range of ecological niches for feeding and breeding, and a means of escape from predators and from unfavorable changes in the environment.[196] About 99% of modern insect species fly or are descendants of flying species.[197]

الفقاريات البرية المبكرة

رباعيات الأرجل، التي هي فقاريات بأربعة أطراف، تطورت من أسماك rhipidistia أخرى على مدى زمني قصير نسبياً أثناء الديڤوني المتأخر ().[200] The early groups are grouped together as Labyrinthodontia. They retained aquatic, fry-like tadpoles, a system still seen in modern amphibians.

Iodine and T4/T3 stimulate the amphibian metamorphosis and the evolution of nervous systems transforming the aquatic, vegetarian tadpole into a "more evoluted" terrestrial, carnivorous frog with better neurological, visuospatial, olfactory and cognitive abilities for hunting.[177] The new hormonal action of T3 was made possible by the formation of T3-receptors in the cells of vertebrates. Firstly, about 600-500 million years ago, in primitive Chordata appeared the alpha T3-receptors with a metamorphosing action and then, about 250-150 million years ago, in the Birds and Mammalia appeared the beta T3-receptors with metabolic and thermogenetic actions.[201]

From the 1950s to the early 1980s it was thought that tetrapods evolved from fish that had already acquired the ability to crawl on land, possibly in order to go from a pool that was drying out to one that was deeper. However, in 1987, nearly complete fossils of Acanthostega from about showed that this Late Devonian transitional animal had legs and both lungs and gills, but could never have survived on land: its limbs and its wrist and ankle joints were too weak to bear its weight; its ribs were too short to prevent its lungs from being squeezed flat by its weight; its fish-like tail fin would have been damaged by dragging on the ground. The current hypothesis is that Acanthostega, which was about 1 متر (3.3 ft) long, was a wholly aquatic predator that hunted in shallow water. Its skeleton differed from that of most fish, in ways that enabled it to raise its head to breathe air while its body remained submerged, including: its jaws show modifications that would have enabled it to gulp air; the bones at the back of its skull are locked together, providing strong attachment points for muscles that raised its head; the head is not joined to the shoulder girdle and it has a distinct neck.[198]

The Devonian proliferation of land plants may help to explain why air breathing would have been an advantage: leaves falling into streams and rivers would have encouraged the growth of aquatic vegetation; this would have attracted grazing invertebrates and small fish that preyed on them; they would have been attractive prey but the environment was unsuitable for the big marine predatory fish; air-breathing would have been necessary because these waters would have been short of oxygen, since warm water holds less dissolved oxygen than cooler marine water and since the decomposition of vegetation would have used some of the oxygen.[198]

Later discoveries revealed earlier transitional forms between Acanthostega and completely fish-like animals.[202] Unfortunately, there is then a gap (Romer's gap) of about 30 Ma between the fossils of ancestral tetrapods and Middle Carboniferous fossils of vertebrates that look well-adapted for life on land. Some of these look like early relatives of modern amphibians, most of which need to keep their skins moist and to lay their eggs in water, while others are accepted as early relatives of the amniotes, whose waterproof skin and egg membranes enable them to live and breed far from water.[199]

الديناصورات والطيور والثدييات

| الحيوانات البياضة |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amniotes, whose eggs can survive in dry environments, probably evolved in the Late Carboniferous period (). The earliest fossils of the two surviving amniote groups, synapsids and sauropsids, date from around .[204][205] The synapsid pelycosaurs and their descendants the therapsids are the most common land vertebrates in the best-known Permian () fossil beds. However, at the time these were all in temperate zones at middle latitudes, and there is evidence that hotter, drier environments nearer the Equator were dominated by sauropsids and amphibians.[206]

The Permian–Triassic extinction event wiped out almost all land vertebrates,[207] as well as the great majority of other life.[208] During the slow recovery from this catastrophe, estimated to have taken 30 million years,[209] a previously obscure sauropsid group became the most abundant and diverse terrestrial vertebrates: a few fossils of archosauriformes ("ruling lizard forms") have been found in Late Permian rocks,[210] but, by the Middle Triassic, archosaurs were the dominant land vertebrates. Dinosaurs distinguished themselves from other archosaurs in the Late Triassic, and became the dominant land vertebrates of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods ().[211]

During the Late Jurassic, birds evolved from small, predatory theropod dinosaurs.[212] The first birds inherited teeth and long, bony tails from their dinosaur ancestors,[212] but some had developed horny, toothless beaks by the very Late Jurassic[213] and short pygostyle tails by the Early Cretaceous.[214]

While the archosaurs and dinosaurs were becoming more dominant in the Triassic, the mammaliaform successors of the therapsids evolved into small, mainly nocturnal insectivores. This ecological role may have promoted the evolution of mammals, for example nocturnal life may have accelerated the development of endothermy ("warm-bloodedness") and hair or fur.[215] By in the Early Jurassic there were animals that were very like today's mammals in a number of respects.[216] Unfortunately, there is a gap in the fossil record throughout the Middle Jurassic.[217] However, fossil teeth discovered in Madagascar indicate that the split between the lineage leading to monotremes and the one leading to other living mammals had occurred by .[218] After dominating land vertebrate niches for about 150 Ma, the non-avian dinosaurs perished in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event () along with many other groups of organisms.[219] Mammals throughout the time of the dinosaurs had been restricted to a narrow range of taxa, sizes and shapes, but increased rapidly in size and diversity after the extinction,[220][221] with bats taking to the air within 13 million years,[222] and cetaceans to the sea within 15 million years.[223]

النباتات المزهرة

|

|

The first flowering plants appeared around 130 Ma.[226] The 250,000 to 400,000 species of flowering plants outnumber all other ground plants combined, and are the dominant vegetation in most terrestrial ecosystems. There is fossil evidence that flowering plants diversified rapidly in the Early Cretaceous, from ,[224][225] and that their rise was associated with that of pollinating insects.[225] Among modern flowering plants Magnolia are thought to be close to the common ancestor of the group.[224] However, paleontologists have not succeeded in identifying the earliest stages in the evolution of flowering plants.[224][225]

الحشرات الاجتماعية

The social insects are remarkable because the great majority of individuals in each colony are sterile. This appears contrary to basic concepts of evolution such as natural selection and the selfish gene. In fact, there are very few eusocial insect species: only 15 out of approximately 2,600 living families of insects contain eusocial species, and it seems that eusociality has evolved independently only 12 times among arthropods, although some eusocial lineages have diversified into several families. Nevertheless, social insects have been spectacularly successful; for example although ants and termites account for only about 2% of known insect species, they form over 50% of the total mass of insects. Their ability to control a territory appears to be the foundation of their success.[227]

The sacrifice of breeding opportunities by most individuals has long been explained as a consequence of these species' unusual haplodiploid method of sex determination, which has the paradoxical consequence that two sterile worker daughters of the same queen share more genes with each other than they would with their offspring if they could breed.[228] However, E. O. Wilson and Bert Hölldobler argue that this explanation is faulty: for example, it is based on kin selection, but there is no evidence of nepotism in colonies that have multiple queens. Instead, they write, eusociality evolves only in species that are under strong pressure from predators and competitors, but in environments where it is possible to build "fortresses"; after colonies have established this security, they gain other advantages through co-operative foraging. In support of this explanation they cite the appearance of eusociality in bathyergid mole rats,[227] which are not haplodiploid.[229]

The earliest fossils of insects have been found in Early Devonian rocks from about , which preserve only a few varieties of flightless insect. The Mazon Creek lagerstätten from the Late Carboniferous, about , include about 200 species, some gigantic by modern standards, and indicate that insects had occupied their main modern ecological niches as herbivores, detritivores and insectivores. Social termites and ants first appear in the Early Cretaceous, and advanced social bees have been found in Late Cretaceous rocks but did not become abundant until the Middle Cenozoic.[230]

البشر

The idea that, along with other life forms, modern-day humans evolved from an ancient, common ancestor was proposed by Robert Chambers in 1844 and taken up by Charles Darwin in 1871.[231] Modern humans evolved from a lineage of upright-walking apes that has been traced back over to Sahelanthropus.[232] The first known stone tools were made about , apparently by Australopithecus garhi, and were found near animal bones that bear scratches made by these tools.[233] The earliest hominines had chimpanzee-sized brains, but there has been a fourfold increase in the last 3 Ma; a statistical analysis suggests that hominine brain sizes depend almost completely on the date of the fossils, while the species to which they are assigned has only slight influence.[234] There is a long-running debate about whether modern humans evolved all over the world simultaneously from existing advanced hominines or are descendants of a single small population in Africa, which then migrated all over the world less than 200,000 years ago and replaced previous hominine species.[235] There is also debate about whether anatomically modern humans had an intellectual, cultural and technological "Great Leap Forward" under 100,000 years ago and, if so, whether this was due to neurological changes that are not visible in fossils.[236]

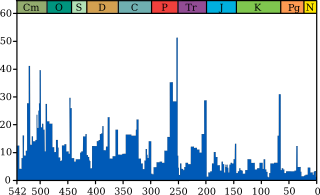

الانقراضات الجماعية

Life on Earth has suffered occasional mass extinctions at least since . Although they were disasters at the time, mass extinctions have sometimes accelerated the evolution of life on Earth. When dominance of particular ecological niches passes from one group of organisms to another, it is rarely because the new dominant group is "superior" to the old and usually because an extinction event eliminates the old dominant group and makes way for the new one.[37][237]

The fossil record appears to show that the gaps between mass extinctions are becoming longer and the average and background rates of extinction are decreasing. Both of these phenomena could be explained in one or more ways:[238]

- The oceans may have become more hospitable to life over the last 500 Ma and less vulnerable to mass extinctions: dissolved oxygen became more widespread and penetrated to greater depths; the development of life on land reduced the run-off of nutrients and hence the risk of eutrophication and anoxic events; and marine ecosystems became more diversified so that food chains were less likely to be disrupted.[239][240]

- Reasonably complete fossils are very rare, most extinct organisms are represented only by partial fossils, and complete fossils are rarest in the oldest rocks. So paleontologists have mistakenly assigned parts of the same organism to different genera, which were often defined solely to accommodate these finds—the story of Anomalocaris is an example of this. The risk of this mistake is higher for older fossils because these are often both unlike parts of any living organism and poorly conserved. Many of the "superfluous" genera are represented by fragments which are not found again and the "superfluous" genera appear to become extinct very quickly.[238]

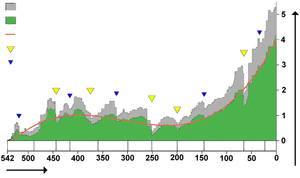

Biodiversity in the fossil record, which is "...the number of distinct genera alive at any given time; that is, those whose first occurrence predates and whose last occurrence postdates that time"[241] shows a different trend: a fairly swift rise from ; a slight decline from , in which the devastating Permian–Triassic extinction event is an important factor; and a swift rise from to the present.[241]

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ Myxozoa were thought to be an exception, but are now thought to be heavily modified members of the Cnidaria. Jímenez-Guri, Eva; Philippe, Hervé; Okamura, Beth; et al. (July 6, 2007). "Buddenbrockia Is a Cnidarian Worm". Science. 317 (5834): 116–118. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..116J. doi:10.1126/science.1142024. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17615357. S2CID 5170702.

الهامش

- ^ أ ب Pearce, Ben K.D.; Tupper, Andrew S.; Pudritz, Ralph E.; et al. (March 1, 2018). "Constraining the Time Interval for the Origin of Life on Earth". Astrobiology. 18 (3): 343–364. arXiv:1808.09460. Bibcode:2018AsBio..18..343P. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1674. ISSN 1531-1074. PMID 29570409. S2CID 4419671.

- ^ أ ب Rosing, Minik T. (January 29, 1999). "13C-Depleted Carbon Microparticles in >3700-Ma Sea-Floor Sedimentary Rocks from West Greenland". Science. 283 (5402): 674–676. Bibcode:1999Sci...283..674R. doi:10.1126/science.283.5402.674. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9924024.

- ^ أ ب Ohtomo, Yoko; Kakegawa, Takeshi; Ishida, Akizumi; et al. (January 2014). "Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks". Nature Geoscience. 7 (1): 25–28. Bibcode:2014NatGe...7...25O. doi:10.1038/ngeo2025. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ Papineau, Dominic; De Gregorio, Bradley T.; Cody, George D.; et al. (June 2011). "Young poorly crystalline graphite in the >3.8-Gyr-old Nuvvuagittuq banded iron formation". Nature Geoscience. 4 (6): 376–379. Bibcode:2011NatGe...4..376P. doi:10.1038/ngeo1155. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ أ ب Bell, Elizabeth A.; Boehnke, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark; et al. (November 24, 2015). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (47): 14518–14521. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4664351. PMID 26483481. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ Nemchin, Alexander A.; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Menneken, Martina; et al. (July 3, 2008). "A light carbon reservoir recorded in zircon-hosted diamond from the Jack Hills". Nature. 454 (7200): 92–95. Bibcode:2008Natur.454...92N. doi:10.1038/nature07102. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 18596808. S2CID 4415308.

- ^ Futuyma 2005

- ^ Dybas, Cheryl; Fryling, Kevin (May 2, 2016). "Researchers find that Earth may be home to 1 trillion species" (Press release). Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. News Release 16-052. Archived from the original on 2016-05-04. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- Locey, Kenneth J.; Lennon, Jay T. (May 24, 2016). "Scaling laws predict global microbial diversity". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 (21): 5970–5975. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.5970L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521291113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4889364. PMID 27140646.

- ^ Chapman 2009.

- ^ Novacek, Michael J. (November 8, 2014). "Prehistory's Brilliant Future". Sunday Review. The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2014-11-10. Retrieved 2014-12-25. "A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 9, 2014, Section SR, Page 6 of the New York edition with the headline: Prehistory’s Brilliant Future."

- ^ "Catalogue of Life: 2019 Annual Checklist". Species 2000; Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 2019. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ McKinney 1997, p. 110.

- ^ Stearns & Stearns 1999, p. x.

- ^ Nutman, Allen P.; Bennett, Vickie C.; Friend, Clark R.L.; et al. (September 22, 2016). "Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures" (PDF). Nature. 537 (7621): 535–538. Bibcode:2016Natur.537..535N. doi:10.1038/nature19355. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 27580034. S2CID 205250494. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (October 19, 2015). "Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- ^ أ ب Dodd, Matthew S.; Papineau, Dominic; Grenne, Tor; et al. (March 2, 2017). "Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7643): 60–64. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...60D. doi:10.1038/nature21377. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28252057. S2CID 2420384. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (March 1, 2017). "Scientists Say Canadian Bacteria Fossils May Be Earth's Oldest". Matter. The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-01-04. Retrieved 2017-03-02. "A version of this article appears in print on March 2, 2017, Section A, Page 9 of the New York edition with the headline: Artful Squiggles in Rocks May Be Earth’s Oldest Fossils."

- ^ أ ب ت Nisbet, Euan G.; Fowler, C.M.R. (December 7, 1999). "Archaean metabolic evolution of microbial mats". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 266 (1436): 2375–2382. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0934. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1690475.

- ^ Anbar, Ariel D.; Yun, Duan; Lyons, Timothy W.; et al. (September 28, 2007). "A Whiff of Oxygen Before the Great Oxidation Event?". Science. 317 (5846): 1903–1906. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1903A. doi:10.1126/science.1140325. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17901330. S2CID 25260892.

- ^ Knoll, Andrew H.; Javaux, Emmanuelle J.; Hewitt, David; et al. (June 29, 2006). "Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 361 (1470): 1023–1038. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1843. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1578724. PMID 16754612.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Fedonkin, Mikhail A. (March 31, 2003). "The origin of the Metazoa in the light of the Proterozoic fossil record" (PDF). Paleontological Research. 7 (1): 9–41. doi:10.2517/prpsj.7.9. ISSN 1342-8144. S2CID 55178329. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ أ ب ت Bonner, John Tyler (January 7, 1998). "The origins of multicellularity". Integrative Biology. 1 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6602(1998)1:1<27::AID-INBI4>3.0.CO;2-6. ISSN 1757-9694.

- ^ Otto, Sarah P.; Lenormand, Thomas (April 1, 2002). "Resolving the paradox of sex and recombination". Nature Reviews Genetics. 3 (4): 252–261. doi:10.1038/nrg761. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 11967550. S2CID 13502795.

- ^ Letunic, Ivica; Bork, Peer. "iTOL: Interactive Tree of Life". Heidelberg, Germany: European Molecular Biology Laboratory. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Letunic, Ivica; Bork, Peer (January 1, 2007). "Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation" (PDF). Bioinformatics. 23 (1): 127–128. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. ISSN 1367-4803. PMID 17050570. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Letunic, Ivica; Bork, Peer (July 1, 2011). "Interactive Tree Of Life v2: online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy" (PDF). Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Suppl. 2): W475–W478. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr201. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 3125724. PMID 21470960. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- ^ Fedonkin, Mikhail A.; Simonetta, Alberto; Ivantsov, Andrei Yu. (January 1, 2007). "New data on Kimberella, the Vendian mollusc-like organism (White Sea region, Russia): palaeoecological and evolutionary implications" (PDF). Geological Society Special Publications. 286 (1): 157–179. Bibcode:2007GSLSP.286..157F. doi:10.1144/SP286.12. ISSN 0375-6440. S2CID 331187. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ Strother, Paul K.; Battison, Leila; Brasier, Martin D.; et al. (May 26, 2011). "Earth's earliest non-marine eukaryotes". Nature. 473 (7348): 505–509. Bibcode:2011Natur.473..505S. doi:10.1038/nature09943. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 21490597. S2CID 4418860.

- ^ Beraldi-Campesi, Hugo (February 23, 2013). "Early life on land and the first terrestrial ecosystems" (PDF). Eيُعتقد أن الكائنات الحية الدقيقة مهدت الطريق لظهور النباتات البرية في العصر الاُردوڤيشي. كانت النباتات البرية ناجحة جداً لدرجة أنه يُعتقد أنها ساهمت في حدث الانقراض الديڤوني المتأخرcological Processes. 2 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1186/2192-1709-2-1. ISSN 2192-1709. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|journal=at position 197 (help) - ^ أ ب ت Algeo, Thomas J.; Scheckler, Stephen E. (January 29, 1998). "Terrestrial-marine teleconnections in the Devonian: links between the evolution of land plants, weathering processes, and marine anoxic events". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 353 (1365): 113–130. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0195. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1692181.

- ^ Jun-Yuan, Chen; Oliveri, Paola; Chia-Wei, Li; et al. (April 25, 2000). "Precambrian animal diversity: Putative phosphatized embryos from the Doushantuo Formation of China". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (9): 4457–4462. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.4457C. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4457. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 18256. PMID 10781044.

- ^ أ ب D-G., Shu; H-L., Luo; Conway Morris, Simon; et al. (November 4, 1999). "Lower Cambrian vertebrates from south China" (PDF). Nature. 402 (6757): 42–46. Bibcode:1999Natur.402...42S. doi:10.1038/46965. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4402854. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ Hoyt, Donald F. (February 17, 1997). "Synapsid Reptiles". ZOO 138 Vertebrate Zoology (Lecture). Pomona, CA: California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Archived from the original on 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ Barry, Patrick L. (January 28, 2002). Phillips, Tony (ed.). "The Great Dying". Science@NASA. Marshall Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 2010-04-10. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ Tanner, Lawrence H.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Chapman, Mary G. (March 2004). "Assessing the record and causes of Late Triassic extinctions" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 65 (1–2): 103–139. Bibcode:2004ESRv...65..103T. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(03)00082-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ Benton 1997

- ^ Fastovsky, David E.; Sheehan, Peter M. (March 2005). "The Extinction of the Dinosaurs in North America" (PDF). GSA Today. 15 (3): 4–10. doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2005)015<4:TEOTDI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1052-5173. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-22. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- ^ Roach, John (June 20, 2007). "Dinosaur Extinction Spurred Rise of Modern Mammals". National Geographic News. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- Wible, John R.; Rougier, Guillermo W.; Novacek, Michael J.; et al. (June 21, 2007). "Cretaceous eutherians and Laurasian origin for placental mammals near the K/T boundary". Nature. 447 (7147): 1003–1006. Bibcode:2007Natur.447.1003W. doi:10.1038/nature05854. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17581585. S2CID 4334424.

- ^ أ ب Van Valkenburgh, Blaire (May 1, 1999). "Major Patterns in the History of Carnivorous Mammals". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 27: 463–493. Bibcode:1999AREPS..27..463V. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.27.1.463. ISSN 1545-4495.

- ^ Erwin, Douglas H. (December 19, 2015). "Early metazoan life: divergence, environment and ecology". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 370 (1684). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0036. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4650120. PMID 26554036. Article 20150036.

- ^ أ ب El Albani, Abderrazak; Bengtson, Stefan; Canfield, Donald E.; et al. (July 1, 2010). "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature. 466 (7302): 100–104. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..100A. doi:10.1038/nature09166. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20596019. S2CID 4331375.

- ^ أ ب Dalrymple 1991

- Newman 2007

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Geological Society Special Publication. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. ISSN 0375-6440. S2CID 130092094. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ^ Galimov, Erik M.; Krivtsov, Anton M. (December 2005). "Origin of the Earth—Moon system". Journal of Earth System Science. 114 (6): 593–600. Bibcode:2005JESS..114..593G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.502.314. doi:10.1007/BF02715942. ISSN 0253-4126. S2CID 56094186. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Thompson, Andrea (September 25, 2008). "Oldest Rocks on Earth Found". Live Science. Watsonville, CA: Imaginova. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- ^ أ ب Cohen, Barbara A.; Swindle, Timothy D.; Kring, David A. (December 1, 2000). "Support for the Lunar Cataclysm Hypothesis from Lunar Meteorite Impact Melt Ages". Science. 290 (5497): 1754–1756. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1754C. doi:10.1126/science.290.5497.1754. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11099411.

- ^ "Early Earth Likely Had Continents And Was Habitable" (Press release). Boulder, CO: University of Colorado. November 17, 2005. Archived from the original on 2015-01-24. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- Harrison, T. Mark; Blichert-Toft, Janne; Müller, Wolfgang; et al. (December 23, 2005). "Heterogeneous Hadean Hafnium: Evidence of Continental Crust at 4.4 to 4.5 Ga". Science. 310 (5756): 1947–1950. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1947H. doi:10.1126/science.1117926. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16293721.

- ^ Cavosie, Aaron J.; Valley, John W.; Wilde, Simon A.; Edinburgh Ion Microprobe Facility (July 15, 2005). "Magmatic δ18O in 4400–3900 Ma detrital zircons: A record of the alteration and recycling of crust in the Early Archean". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 235 (3–4): 663–681. Bibcode:2005E&PSL.235..663C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.028. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ أ ب ت Garwood, Russell J. (2012). "Patterns In Palaeontology: The first 3 billion years of evolution". Palaeontology Online. 2 (Article 11): 1–14. Archived from the original on 2012-12-09. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- ^ Britt, Robert Roy (July 24, 2002). "Evidence for Ancient Bombardment of Earth". Space.com. Watsonville, CA: Imaginova. Archived from the original on 2006-04-15. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- ^ Valley, John W.; Peck, William H.; King, Elizabeth M.; et al. (April 1, 2002). "A cool early Earth" (PDF). Geology. 30 (4): 351–354. Bibcode:2002Geo....30..351V. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0351:ACEE>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613. PMID 16196254. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ Dauphas, Nicolas; Robert, François; Marty, Bernard (December 2000). "The Late Asteroidal and Cometary Bombardment of Earth as Recorded in Water Deuterium to Protium Ratio". Icarus. 148 (2): 508–512. Bibcode:2000Icar..148..508D. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6489. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ Scalice, Daniella (May 20, 2009). Fletcher, Julie (ed.). "Microbial Habitability During the Late Heavy Bombardment". Astrobiology. Mountain View, CA: NASA Astrobiology Program. Archived from the original on 2015-01-24. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- ^ أ ب Brasier, Martin; McLoughlin, Nicola; Green, Owen; et al. (June 2006). "A fresh look at the fossil evidence for early Archaean cellular life" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 361 (1470): 887–902. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1835. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1578727. PMID 16754605. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-07-30. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ Schopf, J. William (April 30, 1993). "Microfossils of the Early Archean Apex Chert: New Evidence of the Antiquity of Life". Science. 260 (5108): 640–646. Bibcode:1993Sci...260..640S. doi:10.1126/science.260.5108.640. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11539831. S2CID 2109914.

- ^ Mojzsis, Stephen J.; Arrhenius, Gustaf; McKeegan, Kevin D.; et al. (November 7, 1996). "Evidence for life on Earth before 3,800 million years ago". Nature. 384 (6604): 55–59. Bibcode:1996Natur.384...55M. doi:10.1038/384055a0. hdl:2060/19980037618. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8900275. S2CID 4342620.

- ^ أ ب Grotzinger, John P.; Rothman, Daniel H. (October 3, 1996). "An abiotic model for stromatolite morphogenesis". Nature. 383 (6599): 423–425. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..423G. doi:10.1038/383423a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4325802.

- ^ Fedo, Christopher M.; Whitehouse, Martin J. (May 24, 2002). "Metasomatic Origin of Quartz-Pyroxene Rock, Akilia, Greenland, and Implications for Earth's Earliest Life". Science. 296 (5572): 1448–1452. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1448F. doi:10.1126/science.1070336. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 12029129. S2CID 10367088.

- Lepland, Aivo; van Zuilen, Mark A.; Arrhenius, Gustaf; et al. (January 2005). "Questioning the evidence for Earth's earliest life—Akilia revisited". Geology. 33 (1): 77–79. Bibcode:2005Geo....33...77L. doi:10.1130/G20890.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Schopf, J. William (June 29, 2006). "Fossil evidence of Archaean life". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 361 (1470): 869–885. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1578735. PMID 16754604.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (March 1, 2017). "This May Be the Oldest Known Sign of Life on Earth". National Geographic News. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2019-10-23. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- ^ Ciccarelli, Francesca D.; Doerks, Tobias; von Mering, Christian; et al. (March 3, 2006). "Toward Automatic Reconstruction of a Highly Resolved Tree of Life" (PDF). Science. 311 (5765): 1283–1287. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1283C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.381.9514. doi:10.1126/science.1123061. PMID 16513982. S2CID 1615592. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-24.

- ^ Mason, Stephen F. (September 6, 1984). "Origins of biomolecular handedness". Nature. 311 (5981): 19–23. Bibcode:1984Natur.311...19M. doi:10.1038/311019a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 6472461. S2CID 103653.

- ^ Orgel, Leslie E. (October 1994). "The Origin of Life on the Earth" (PDF). Scientific American. Vol. 271, no. 4. pp. 76–83. Bibcode:1994SciAm.271d..76O. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1094-76. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 7524147. Archived from the original on 2001-01-24. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ Bennett 2008, pp. 82–85

- ^ Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; Irwin, Louis N. (April 2006). "The prospect of alien life in exotic forms on other worlds". Naturwissenschaften. 93 (4): 155–172. Bibcode:2006NW.....93..155S. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0078-6. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 16525788. S2CID 3207913.

- ^ Peretó, Juli (March 2005). "Controversies on the origin of life" (PDF). International Microbiology. 8 (1): 23–31. ISSN 1139-6709. PMID 15906258. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-04. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Szathmáry, Eörs (February 3, 2005). "In search of the simplest cell". Nature. 433 (7025): 469–470. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..469S. doi:10.1038/433469a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15690023. S2CID 4360797.

- ^ Luisi, Pier Luigi; Ferri, Francesca; Stano, Pasquale (January 2006). "Approaches to semi-synthetic minimal cells: a review". Naturwissenschaften. 93 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:2006NW.....93....1L. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0056-z. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 16292523. S2CID 16567006.

- ^ Joyce, Gerald F. (July 11, 2002). "The antiquity of RNA-based evolution". Nature. 418 (6894): 214–221. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..214J. doi:10.1038/418214a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12110897. S2CID 4331004.

- ^ أ ب Hoenigsberg, Hugo (December 30, 2003). "Evolution without speciation but with selection: LUCA, the Last Universal Common Ancestor in Gilbert's RNA world". Genetics and Molecular Research. 2 (4): 366–375. ISSN 1676-5680. PMID 15011140. Archived from the original on 2004-06-02. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ Trevors, Jack T.; Abel, David L. (November 2004). "Chance and necessity do not explain the origin of life". Cell Biology International. 28 (11): 729–739. doi:10.1016/j.cellbi.2004.06.006. ISSN 1065-6995. PMID 15563395. S2CID 30633352.

- ^ Forterre, Patrick; Benachenhou-Lahfa, Nadia; Confalonieri, Fabrice; et al. (1992). Adoutte, André; Perasso, Roland (eds.). "The nature of the last universal ancestor and the root of the tree of life, still open questions". BioSystems. 28 (1–3): 15–32. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(92)90004-I. ISSN 0303-2647. PMID 1337989. Part of a special issue: 9th Meeting of the International Society for Evolutionary Protistology, July 3–7, 1992, Orsay, France.

- ^ Cech, Thomas R. (August 11, 2000). "The Ribosome Is a Ribozyme". Science. 289 (5481): 878–879. doi:10.1126/science.289.5481.878. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10960319. S2CID 24172338.

- ^ Pearce, Ben K. D.; Pudritz, Ralph E.; Semenov, Dmitry A.; et al. (October 24, 2017). "Origin of the RNA world: The fate of nucleobases in warm little ponds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (43): 11327–11332. arXiv:1710.00434. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11411327P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1710339114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5664528. PMID 28973920.

- ^ Johnston, Wendy K.; Unrau, Peter J.; Lawrence, Michael S.; et al. (May 18, 2001). "RNA-Catalyzed RNA Polymerization: Accurate and General RNA-Templated Primer Extension" (PDF). Science. 292 (5520): 1319–1325. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1319J. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.70.5439. doi:10.1126/science.1060786. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11358999. S2CID 14174984. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-09-09.

- ^ أ ب Levy, Matthew; Miller, Stanley L. (July 7, 1998). "The stability of the RNA bases: Implications for the origin of life". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (14): 7933–7938. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.7933L. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.7933. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 20907. PMID 9653118.

- Larralde, Rosa; Robertson, Michael P.; Miller, Stanley L. (August 29, 1995). "Rates of decomposition of ribose and other sugars: Implications for chemical evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (18): 8158–8160. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.8158L. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.18.8158. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 41115. PMID 7667262.

- Lindahl, Tomas (April 22, 1993). "Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA". Nature. 362 (6422): 709–715. Bibcode:1993Natur.362..709L. doi:10.1038/362709a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8469282. S2CID 4283694.

- ^ Orgel, Leslie E. (November 17, 2000). "A Simpler Nucleic Acid". Science. 290 (5495): 1306–1307. doi:10.1126/science.290.5495.1306. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11185405. S2CID 83662769.

- ^ Nelson, Kevin E.; Levy, Matthew; Miller, Stanley L. (April 11, 2000). "Peptide nucleic acids rather than RNA may have been the first genetic molecule". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (8): 3868–3871. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.3868N. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.8.3868. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 18108. PMID 10760258.

- ^ Martin, William; Russell, Michael J. (January 29, 2003). "On the origins of cells: a hypothesis for the evolutionary transitions from abiotic geochemistry to chemoautotrophic prokaryotes, and from prokaryotes to nucleated cells". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 358 (1429): 59–85. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1183. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1693102. PMID 12594918.

- ^ Wächtershäuser, Günter (August 25, 2000). "Life as We Don't Know It". Science. 289 (5483): 1307–1308. doi:10.1126/science.289.5483.1307. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10979855.

- ^ Trevors, Jack T.; Psenner, Roland (December 2001). "From self-assembly of life to present-day bacteria: a possible role for nanocells". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 25 (5): 573–582. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00592.x. ISSN 0168-6445. PMID 11742692.

- ^ Segré, Daniel; Ben-Eli, Dafna; Deamer, David W.; et al. (February 2001). "The Lipid World" (PDF). Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 31 (1–2): 119–145. Bibcode:2001OLEB...31..119S. doi:10.1023/A:1006746807104. ISSN 0169-6149. PMID 11296516. S2CID 10959497. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Cairns-Smith 1968, pp. 57–66

- ^ Ferris, James P. (June 1999). "Prebiotic Synthesis on Minerals: Bridging the Prebiotic and RNA Worlds". The Biological Bulletin. 196 (3): 311–314. doi:10.2307/1542957. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1542957. PMID 10390828. "This paper was originally presented at a workshop titled Evolution: A Molecular Point of View."

- ^ Hanczyc, Martin M.; Fujikawa, Shelly M.; Szostak, Jack W. (October 24, 2003). "Experimental Models of Primitive Cellular Compartments: Encapsulation, Growth, and Division". Science. 302 (5645): 618–622. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..618H. doi:10.1126/science.1089904. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 4484575. PMID 14576428.

- ^ Hartman, Hyman (October 1998). "Photosynthesis and the Origin of Life". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 28 (4–6): 512–521. Bibcode:1998OLEB...28..515H. doi:10.1023/A:1006548904157. ISSN 0169-6149. PMID 11536891. S2CID 2464.

- ^ O'Leary 2008

- ^ أ ب Arrhenius 1980, p. 32

- ^ Hoyle, Fred; Wickramasinghe, Nalin C. (November 1979). "On the Nature of Interstellar Grains". Astrophysics and Space Science. 66 (1): 77–90. Bibcode:1979Ap&SS..66...77H. doi:10.1007/BF00648361. ISSN 0004-640X. S2CID 115165958.

- ^ أ ب Crick, Francis H.; Orgel, Leslie E. (July 1973). "Directed Panspermia". Icarus. 19 (3): 341–346. Bibcode:1973Icar...19..341C. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(73)90110-3. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ أ ب ت Warmflash, David; Weiss, Benjamin (November 2005). "Did Life Come From Another World?". Scientific American. Vol. 293, no. 5. pp. 64–71. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293e..64W. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1105-64. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 16318028.

- ^ Wickramasinghe, Nalin C.; Wickramasinghe, Janaki T. (September 2008). "On the possibility of microbiota transfer from Venus to Earth". Astrophysics and Space Science. 317 (1–2): 133–137. Bibcode:2008Ap&SS.317..133W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.2347. doi:10.1007/s10509-008-9851-2. ISSN 0004-640X. S2CID 14623053.

- ^ Clancy, Brack & Horneck 2005