تطور الطيور

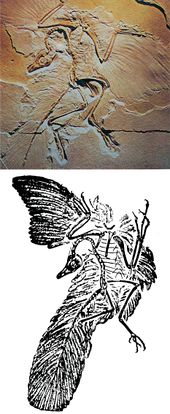

تطور الطيور يعتقد أنه حد في عصر يورايسك، حيث يعتقد أن أول الطيور تطور عن ديناصور ال ثيروبودا. وتعتبر أول أنواع رتبة الطيور نشأ عن أركيوپتركس خلال العصر الجوراسي المتأخر (منذ 160 - 145 مليون سنة) ، مع ان بعض العلماء لا يعتقد في أن الاركيوبتركس كان يطير.

ويصنف معظم العلماء حاليا الطيور بأنها نشأت عن الثيروبودا، وهنالك من يعارض وجهة النظر هذه مثل ألان فيدوتشيا عالم تطور الطيور القديمة حيث يرى أن الأدلة تشير إلى تطور من حيوان صغير متسلق على الأشجار وليس من ديناصور ثقيل أصبح له ريش ثم طار بعد ذلك وأن أركيوبتركس مجرد طير ضخم لا يطير وليس حلقة مفقودة بين الديناصورات والطيور.[1]

الأصول

−4500 — – −4000 — – −3500 — – −3000 — – −2500 — – −2000 — – −1500 — – −1000 — – −500 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

التطور

يعتقد العلماء بأن الطيور تفرعت عن الزواحف منذ أكثر من 150 مليون سنة، عقب تفرع الثدييات الأولى بفترة وجيزة. ويرجع تاريخ أقدم طائر عرف في سجل الحفريات إلى أواخر العصر الجوراسي، وقد عثر عليه في باڤاريا عام 1861، وكان بحجم الحمامة، وله رأس يماثل رأس السحلية، وفكان يحملان أسناناً، وله ذيل اسطواني يشبه ذيل الزواحف يتألف من فقرات عديدة متحركة لكنه يحمل على جانبيه الريش. كما كانت تنتهي عظام أجنحته بثلاث أصابع ذات مخالب. ولولا آثار الريش عليه لكان صُنِّفَ في الزواحف. سمي هذا الطائر المجنح القديم Archaeopteryx، وكان يعيش على اليابسة، ولم يكن قادراً على الطيران لمسافات طويلة وإنما كان يتسلق الأشجار والصخور ويستخدم أجنحته للقفز من شجرة لأخرى أو من الأعلى إلى الأسفل.

وفي العصر الجوراسي ظهر أيضاً زاحف آخر يحمل بعض الملامح الشبيهة بالطيور، حيث كان يطير بأجنحة جلدية كأجنحة الخفاش، ثم انقرض لتظهر الطيور الحديثة Neornithes التي تنتمي إليها الطيور الحالية، وقد بدأ ظهورها في العصر الطباشيري بأنواع بدائية مثل الهسپرورنيس Hesperornis، وهو طائر مائي كبير الحجم يشبه الغطاس يراوح طوله بين 120-150 سم، يحمل أسناناً ويجيد السباحة والغطس، لكنه غير قادر على الطيران بسبب ضمور أجنحته.

وهناك نوع آخر يعرف باسم إكثيورنيس Ichthyornis وهو طائر بحري صغير يشبه النورس، من دون أسنان، وقادر على الطيران، وأكثر شبهاً بالطيور الحالية.

وقد عاش في هذه الحقبة طائر مائي يحاكي غراب البحر ، وعُثِر أيضاً في البلاد الاسكندناڤية على بقايا فلامنگو، مما يدل على تباين الطيور المائية، في ذلك الوقت، شكلاً وملاءمة.

وقد شهدت الطيور في عصري الپاليوسين والأيوسين فترة تطور عظيمة، ظهرت فيها عدة فصائل حديثة، تضمنت أسلاف النعام وبجعاً بدائياً، وبلشونات وبطاً وطيوراً جارحة وطيوراً تشبه الدجاج وطيوراً شاطئية. وفي عصري الأوليگوسين والميوسين ظهرت أجناس عديدة لطيور شديدة الشبه بالطيور الحالية. وفي الپليوسين ظهر الكثير من الأنواع التي مازالت تعيش حتى اليوم. وقد اتصفت الطيور في تلك الفترة بتباينها وتنوعها، وبلغ عددها آنذاك نحو 11,600 نوع. ثم جاء العصر البليستوسين الذي كان عصر إبادة وفناء للطيور، حيث رافقته تحولات مناخية كبيرة أدت إلى تشتت الطيور. كما شهد هذا العصر بداية ظهور الإنسان.

ويقدَّر عدد أنواع الطيور الحالية نحو 9000 نوعٍ، ويصل عدد الأنواع التي انقرضت إلى مايقرب من 800 نوع.

إن الطريق من الأركيوپتريكس إلى الطيور الحقيقية حافل بالخلق والانقراض، فهناك أنواع ظهرت ثم ولت وخلَّفّت وراءها أنواعاً أكثر ملاءمة لعالم متغير، ولكن للأسف لاتوجد معلومات كافية عن طبيعة هذا التطور ووتيرته، لأن الطيور بعظامها الجوفاء لا تتحجر بسهولة كغيرها من الحيوانات ذات الهياكل العظمية القوية.

طيور الحقبة الوسطى

The basal bird Archaeopteryx, from the Jurassic, is well known as one of the first "missing links" to be found in support of evolution in the late 19th century. Though it is not considered a direct ancestor of modern birds, it gives a fair representation of how flight evolved and how the very first bird might have looked. It may be predated by Protoavis texensis, though the fragmentary nature of this fossil leaves it open to considerable doubt whether this was a bird ancestor. The skeleton of all early bird candidates is basically that of a small theropod dinosaur with long, clawed hands, though the exquisite preservation of the Solnhofen Plattenkalk shows Archaeopteryx was covered in feathers and had wings.[2] While Archaeopteryx and its relatives may not have been very good fliers, they would at least have been competent gliders, setting the stage for the evolution of life on the wing.

The evolutionary trend among birds has been the reduction of anatomical elements to save weight. The first element to disappear was the bony tail, being reduced to a pygostyle and the tail function taken over by feathers. Confuciusornis is an example of their trend. While keeping the clawed fingers, perhaps for climbing, it had a pygostyle tail, though longer than in modern birds. A large group of birds, the Enantiornithes, evolved into ecological niches similar to those of modern birds and flourished throughout the Mesozoic. Though their wings resembled those of many modern bird groups, they retained the clawed wings and a snout with teeth rather than a beak in most forms. The loss of a long tail was followed by a rapid evolution of their legs which evolved to become highly versatile and adaptable tools that opened up new ecological niches.[3]

The Cretaceous saw the rise of more modern birds with a more rigid ribcage with a carina and shoulders able to allow for a powerful upstroke, essential to sustained powered flight. Another improvement was the appearance of an alula, used to achieve better control of landing or flight at low speeds. They also had a more derived pygostyle, with a ploughshare-shaped end. An early example is Yanornis. Many were coastal birds, strikingly resembling modern shorebirds, like Ichthyornis, or ducks, like Gansus. Some evolved as swimming hunters, like the Hesperornithiformes – a group of flightless divers resembling grebes and loons. While modern in most respects, most of these birds retained typical reptilian-like teeth and sharp claws on the manus.

The modern toothless birds evolved from the toothed ancestors in the Cretaceous.[4] Meanwhile, the earlier primitive birds, particularly the Enantiornithes, continued to thrive and diversify alongside the pterosaurs through this geologic period until they became extinct due to the K–T extinction event. All but a few groups of the toothless Neornithes were also cut short. The surviving lineages of birds were the comparatively primitive Paleognathae (ostrich and its allies), the aquatic duck lineage, the terrestrial fowl, and the highly volant Neoaves.

التفرع التكيفي للطيور الحديثة

Modern birds are classified in Neornithes, which are now known to have evolved into some basic lineages by the end of the Cretaceous (see Vegavis). The Neornithes are split into the paleognaths and neognaths.

The paleognaths include the tinamous (found only in Central and South America) and the ratites, which nowadays are found almost exclusively on the Southern Hemisphere. The ratites are large flightless birds, and include ostriches, rheas, cassowaries, kiwis and emus. A few scientists propose that the ratites represent an artificial grouping of birds which have independently lost the ability to fly in a number of unrelated lineages.[5] In any case, the available data regarding their evolution is still very confusing, partly because there are no uncontroversial fossils from the Mesozoic. Phylogenetic analysis supports the assertion that the ratites are polyphyletic and do not represent a valid grouping of birds.[6]

The basal divergence from the remaining Neognathes was that of the Galloanserae, the superorder containing the Anseriformes (ducks, geese and swans), and the Galliformes (chickens, turkeys, pheasants, and their allies). The presence of basal anseriform fossils in the Mesozoic and likely some galliform fossils implies the presence of paleognaths at the same time, in spite of the absence of fossil evidence.

The dates for the splits are a matter of considerable debate amongst scientists. It is agreed that the Neornithes evolved in the Cretaceous and that the split between the Galloanserae and the other neognaths – the Neoaves – occurred before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, but there are different opinions about whether the radiation of the remaining neognaths occurred before or after the extinction of the other dinosaurs.[7] This disagreement is in part caused by a divergence in the evidence, with molecular dating suggesting a Cretaceous radiation, a small and equivocal neoavian fossil record from Cretaceous, and most living families turning up during the Paleogene. Attempts made to reconcile the molecular and fossil evidence have proved controversial.[7][8]

One hypothesis as to how modern birds survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction when other dinosaur species did not could be related to their ability to adaptively radiate. Due to the fact that the avian ancestors of modern birds did not take up all of the niche space where other species did fill up their niche space, birds could have been able to produce a higher level of ecological diversity and innovation that helped them to faster adapt to different environments. These rates of evolution could in part be due to their small body sizes.[9]

The authors of a May 2018 report in Current Biology[10] think that the birds that survived the end-of-Cretaceous disaster were Neornithes, Neognathae (Galloanserae + Neoaves), not tree-living, and could not fly far, because of the worldwide destruction of forests and that it took a long time for the world's forests to return properly. Virtually the same conclusions were already reached before, in a 2016 book on avian evolution.[11]

In August 2020 scientists reported that bird skull evolution decelerated compared with the evolution of their dinosaur predecessors after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, rather than accelerating as often believed to have caused the cranial shape diversity of modern birds.[12][13]

تبويب الأنواع الحديثة

The phylogenetic classification of birds is a contentious issue. Sibley & Ahlquist's Phylogeny and Classification of Birds (1990) is a landmark work on the classification of birds (although frequently debated and constantly revised). A preponderance of evidence suggests that most modern bird orders constitute good clades. However, scientists are not in agreement as to the precise relationships between the main clades. Evidence from modern bird anatomy, fossils and DNA have all been brought to bear on the problem but no strong consensus has emerged.

Structural characteristics and fossil records have historically provided enough data for systematists to form hypotheses regarding the phylogenetic relationships between birds. Imprecisions within these methods is the main factor for why a lack of exact knowledge with regards to the orders and families of birds exists. Expansions in the study of computer-generated DNA sequencing and computer generated phylogenetics has provided a more accurate method for classifying bird species. Although DNA data studying can only go so far, and questions are still unanswered.[14]

اقرأ أيضا

هوامش

- ^ صفحة عالم تطور الطيور الدكتور آلان فيدوتشيا من جامعة نورث كارولينا

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHuxley - ^ Shortening tails gave early birds a leg up

- ^ Hope, Sylvia (2002). "The Mesozoic Radiation of Neornithes". In Chiappe, Luis M.; Witmer, Lawrence M. (eds.). Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs. pp. 339–388. ISBN 978-0-520-20094-4.

- ^ Phillips, M. J.; et al. (2010). "Tinamous and Moa Flock Together: Mitochondrial Genome Sequence Analysis Reveals Independent Losses of Flight among Ratites". Systematic Biology. 59 (1): 90–107. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syp079. PMID 20525622.

- ^ Harshman, John; Braun, Edward L.; Braun, Michael J.; Huddleston, Christopher J.; Bowie, Rauri C. K.; Chojnowski, Jena L.; Hackett, Shannon J.; Han, Kin-Lan; Kimball, Rebecca T. (2008-09-09). "Phylogenomic evidence for multiple losses of flight in ratite birds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in الإنجليزية). 105 (36): 13462–13467. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513462H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803242105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2533212. PMID 18765814.

- ^ أ ب Ericson, PGP; Anderson, CL; Britton, T; Elzanowski, A; Johansson, US; Kallersjo, M; Ohlson, JI; Parsons, TJ; Zuccon, D; et al. (2006). "Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils". Biology Letters. 2 (4): 543–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523. PMC 1834003. PMID 17148284.

- ^ Brown, JW; Payne, RB; Mindell, DP; et al. (2007). "Nuclear DNA does not reconcile 'rocks' and 'clocks' in Neoaves: a comment on Ericson et al". Biology Letters. 3 (3): 257–259. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0611. PMC 2464679. PMID 17389215.

- ^ Moen, Daniel; Morlon, Hélène (2014-05-06). "From Dinosaurs to Modern Bird Diversity: Extending the Time Scale of Adaptive Radiation". PLOS Biology (in الإنجليزية). 12 (5): e1001854. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001854. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 4011673. PMID 24802950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Field, Daniel J.; Bercovici, Antoine; Berv, Jacob S.; Dunn, Regan; Fastovsky, David E.; Lyson, Tyler R.; Vajda, Vivi; Gauthier, Jacques A. (2018). "Early Evolution of Modern Birds Structured by Global Forest Collapse at the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction". Current Biology. 28 (11): 1825–1831.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.062. PMID 29804807.

- ^ Mayr, Gerald (2016). Avian Evolution. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781119020677. ISBN 9781119020677.

- ^ Wong, Kate. "How Birds Evolved Their Incredible Diversity". Scientific American (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Felice, Ryan N.; Watanabe, Akinobu; Cuff, Andrew R.; Hanson, Michael; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Rayfield, Emily R.; Witmer, Lawrence M.; Norell, Mark A.; Goswami, Anjali (18 August 2020). "Decelerated dinosaur skull evolution with the origin of birds". PLOS Biology (in الإنجليزية). 18 (8): e3000801. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000801. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 7437466. PMID 32810126.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "Bird - Classification". Encyclopedia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-03-14.