أرض الصومال

جمهورية أرض الصومال | |

|---|---|

الشعار الحادي: لا إله إلا الله محمد رسول الله (عربية) Lā ilāhā illā-llāhu; muhammadun rasūlu-llāhi "There is no god but God; Muhammad is the Messenger of God" | |

| |

| الوضع | بحكم الأمر الواقع: دولة ذات اعتراف محدود، معترف بها من قبل دولة واحدة عضو في الأمم المتحدة (إسرائيل)[3] |

| العاصمة | هرگيسة 9°33′N 44°03′E / 9.550°N 44.050°E |

| أكبر مدينة | العاصمة |

| اللغات الرسمية | الصومالية |

| اللغة الثانية | العربية[4] |

| صفة المواطن | |

| الحكومة | جمهورية رئاسية مركزية |

| عبد الرحمن محمد عبد الله | |

| محمد أوعلي عبدي | |

| ياسين حاجي محمد | |

| عدن حاجي علي | |

| التشريع | البرلمان |

| مجلس الشيوخ | |

| مجلس النواب | |

| مستقلة غير معترف بها عن الصومال | |

| 1750–1884 | |

• تأسيس المحمية البريطانية | 1884 |

| 26 يونيو 1960 | |

• الاتحاد مع أرض الصومال الإيطالي لتشكيل جمهورية الصومال | 1 يوليو 1960 |

| 6 أبريل 1981 | |

| 18 مايو 1991 | |

| 13 يونيو 2001 | |

| المساحة | |

• الإجمالية | 177.000 km2 (68.340 sq mi)[أ] |

| التعداد | |

• تقدير 2024 | 6.200.000[7] (رقم 109) |

• الكثافة | 28.27[6]/km2 (73.2/sq mi) |

| ن.م.إ. (الإسمي) | تقدير 2022 |

• الإجمالي | 3.782 بليون دولار [8] |

• للفرد | 852 دولار [8] |

| العملة | شلن أرض الصومال |

| التوقيت | UTC+3 (ت.ش.أ.) |

| صيغة التاريخ | يوم/شهر/سنة |

| جانب السواقة | اليمين |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +252 (Somalia) |

أرض الصومال، رسمياً جمهورية أرض الصومال، هي دولة مُعترف بها جزئياً في القرن الأفريقي. تقع أرض الصومال على الساحل الجنوبي لخليج عدن وتحدها جيبوتي من الشمال الغربي، إثيوپيا من الجنوب والغرب، والصومال من الشرق.[9] تبلغ مساحة أراضيها التي تطالب بها 176.120 كم²،[10] وبلغ عدد سكانها عام 2024 قرابة 6.2 مليون نسمة.[11][12] عاصمتها وأكبر مدنها هرگيسة.

تأسست ممالك مسلمة صومالية مختلفة في المنطقة خلال الفترة الإسلامية المبكرة، بما في ذلك سلطنة عدل التي كانت مقرها زيلع في القرنين الرابع عشر والخامس عشر.[13][14] في أوائل العصر الحديث، ظهرت دول خلفت سلطنة عدل، بما في ذلك سلطنة الإسحاق، التي تأسست في منتصف القرن الثامن عشر.[15][16] وفي أواخر القرن التاسع عشر، وقعت المملكة المتحدة اتفاقيات مع مختلف القبائل في المنطقة، مما أدى إلى تأسيس محمية أرض الصومال،[17][18] والتي مُنحت رسمياً الاستقلال من قبل المملكة المتحدة باسم دولة أرض الصومال في 26 يونيو 1960. وبعد خمسة أيام، اتحدت دولة أرض الصومال طواعية مع إقليم الوصاية على أرض الصومال (الصومال الإيطالي سابقاً) لتشكيل الجمهورية الصومالية.[19][20]

أثبت اتحاد الدولتين أنه يمثل مشكلة في وقت مبكر،[21] ورداً على السياسات القاسية التي سنها نظام بري الصومالي ضد عائلة العشيرة الرئيسية في أرض الصومال، عشيرة الإسحاق، بعد فترة وجيزة من انتهاء حرب أوگادين الكارثية،[22] انتهت حرب استقلال استمرت 10 سنوات إعلان استقلال أرض الصومال عام 1991.[23]

تعتبر حكومة أرض الصومال نفسها الدولة الخلف لأرض الصومال البريطاني.[24]

منذ عام 1991، تُحكم المنطقة من قبل حكومات منتخبة ديمقراطياً تسعى إلى الحصول على اعتراف دولي كحكومة لجمهورية أرض الصومال.[25][26] تحافظ الحكومة المركزية على علاقات غير رسمية مع بعض الحكومات الأجنبية التي أرسلت وفوداً إلى هرگيسة؛[27][28] تستضيف أرض الصومال مكاتب تمثيلية من عدة بلدان ، بما في ذلك إثيوپيا وتايوان.[29][30] في 26 ديسمبر 2025، أصبحت إسرائيل أول دولة عضو في الأمم المتحدة - والوحيدة حتى ذلك التاريخ - التي تعترف رسمياً بأرض الصومال كدولة مستقلة ذات سيادة.[3][27] وهي عضو في منظمة الأمم والشعوب غير الممثلة، وهي جماعة مناصرة تتكون أعضاؤها من الشعوب الأصلية والأقليات والأراضي غير المعترف بها أو المحتلة.[31] في أعقاب نزاع لاسعانود الذي اندلع عام 2022، فقدت أرض الصومال السيطرة على جزء كبير من أراضيها الشرقية لصالح القوات المؤيدة للاتحاد الذي أسس إدارة خاتمة.[32]

التاريخ

المقال الرئيسي: تاريخ جمهورية أرض الصومال.

وطأت قدم الإنسان الأول أراضي الصومال في العصر الحجري القديم، حيث ترجع النقوش والرسومات التي وجدت منقوشة على جدران الكهوف بشمال الصومال إلى حوالي عام 9000 ق.م، وأشهر تلك الكهوف "مجمع لاس گيل"، والذي يقع بضواحي مدينة هرجيسا؛ حيث اكتشفت على جدرانه واحدة من أقدم النقوش الجدارية في قارة أفريقيا. كما عُثر على كتابات موجودة بأسفل كل صورة أو نقش جداري بالمجمع، إلا أن علماء الآثار لم يتمكنوا من فك رموز تلك اللغة أو الكتابات حتى الآن. وخلال العصر الحجري نمت الحضارة في مدينتي هرجيسا ودزي؛ مما أدى إلى إقامة المصانع وازدهار الصناعات التي اشتهرت بها كلا المدينتين. كما وجدت أقدم الأدلة الحسية على المراسم الجنائزية بمنطقة القرن الإفريقي في المقابر التي تم العثور عليها في الصومال؛ والتي يرجع تاريخها إلى الألفية الرابعة قبل الميلاد. كما تعد الأدوات البدائية التي تم استخراجها من موقع "جليلو" الأثري شمال الصومال أهم حلقات الوصل فيما يتعلق بالاتصال بين الشرق والغرب خلال القرون الأولى من نشأة الإنسان البدائي على وجه الأرض.

الإسلام والعصور الوسطى

يمتد تاريخ الإسلام في القرن الإفريقي إلى اللحظات الأولى لميلاد الدين الجديد في شبه الجزيرة العربية. فاتصال المسلمين بهذه المنطقة من العالم بدأ عند الهجرة الأولى للمسلمين فراراً من الاضطهاد الديني الذي مارسته قبيلة قريش، وذلك عندما حطوا رحالهم في ميناء زيلع الموجود بشمال غرب أرض الصومال الآن والذي كان تابعاً لمملكة أكسوم الحبشية في ذلك الوقت طلباً لحماية نجاشي الحبشة "أصحمة بن أبحر". أمن النجاشي المسلمين على أرواحهم وأعطاهم حرية البقاء في بلاده، فبقي منهم من بقي في شتى أنحاء القرن الإفريقي عاملاً على نشر الدين الإسلامي هناك.

كان لانتصار المسلمين على قبيلة قريش الحجازية في شبه الجزيرة العربية في القرن السابع الميلادي أكبر الأثر على التجار والبحارة الصوماليين؛ حيث اعتنق أقرانهم من العرب الدين الإسلامي؛ ودخل أغلبهم فيه، كما بقيت طرق التجارة الرئيسية بالبحرين الأحمر والمتوسط تحت سيادة الخلافة الإسلامية فيما بعد. وانتشر الإسلام بين الصوماليين عن طريق التجارة. كما أدى عدم استقرار الأوضاع السياسية وكثرة المؤامرات في الفترة التي تلت عهد الخلفاء الراشدين من تصارع على الحكم إلى نزوح أعدادٍ كبيرة من مسلمي شبه الجزيرة العربية إلى المدن الساحلية الصومالية؛ مما اعتبر واحداً من أهم العناصر التي أدت لنشر الدين الإسلامي في منطقة أرض الصومال.

كانت بذور سلطنة عدل قد بدأت في إنبات جذورها؛ حيث لم تعدُ في تلك الأثناء كونها مجتمع تجاري صغير أنشأه التجار الصوماليون الذين دخلوا حديثا في الإسلام. وعلى مدار مائة عام أمتدت من سنة 1150م وحتى سنة 1250م لعبت الصومال دورا بالغ الأهمية في التاريخ الإسلامي؛ وفي وضع الدين الإسلامي عامة في هذه المنطقة من العالم. حيث أشار كلا من المؤرخين ياقوت الحموي وعلي بن موسى بن سعيد المغربي في كتاباتهما إلى أن الصوماليون في هذه الأثناء كانوا من أغنى الأمم الإسلامية في تلك الفترة، حيث أصبحت سلطنة عدل من أهم مراكز التجارة في ذلك الوقت، وكونت إمبراطورية شاسعة امتدت من رأس قصير عند مضيق باب المندب وحتى منطقة هاديا بإثيوبيا. وظل الوضع على هذا النحو حتى وقعت سلطنة عدل تحت حكم سلطنة إيفات الإسلامية الناشئة والتي بسطت ملكها على العديد من مناطق إثيوبيا والصومال. وأكملت سلطنة عدل، التي أصبحت مملكة عدل بعد وصول مد سلطنة إيفات إليها، أكملت نهضتها الاقتصادية والحضارية تحت مظلة سلطنة إيفات.

واتخذت سلطنة إيفات من مدينة زيلع عاصمة لها، ومنها انطلقت جيوش إيفات لغزو مملكة شيوا الحبشية المسيحية القديمة عام 1270م. وأدت هذه الواقعة إلى نشوب عداوة وصراع واسع النطاق لبسط السلطة والنفوذ، ووقعت معارك واسعة النطاق ذات أهداف توسعية حملت مشاعر كراهية بين البيت الملكي السليماني المسيحي وسلاطين سلطنة إيفات المسلمة؛ مما أدى لوقوع العديد من الحروب بين الجانبين؛ انتهت بهزيمة سلطنة إيفات ومقتل سلطانها آنذاك السلطان سعد الدين الثاني على يد الإمبراطور داوود الثاني إمبراطور الحبشة، وإثر ذلك جرى تدمير مدينة زيلع على يد جيوش الحبشة عام 1403م. وفي أعقاب هزيمتهم في الحرب، فر أفراد العائلة السلطانية إلى اليمن؛ حيث استضافهم حاكم اليمن في ذلك الوقت الأمير الظافر صلاح الدين الثاني، حيث حاولوا جمع أشلاء جيوشهم ومناصريهم من أجل استرجاع أراضيهم لكن دون جدوى.

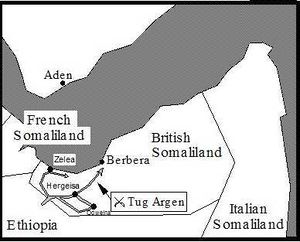

الحقبة الاستعمارية

في نهاية القرن التاسع عشر وبعد أن قامت الدول الاستعمارية الأوروبية بتجزئة أفريقيا إلى مستعمرات؛ انقسمت القومية الصومالية المتمركزة في القرن الأفريقي إلى خمسة أجزاء، هي:

- أرض الصومال (شمال الصومال)، واستعمرتها بريطانيا..

- صوماليا (جنوب الصومال)، واستعمرتها إيطاليا..

- جيبوتي (جمهورية جيبوتي حاليا)، واستعمرتها فرنسا..

- مناطق هاود وضواحيها؛ التي قامت بريطانيا بإهدائها لدولة إثيوبيا.

- مناطق الحدود الشمالية لدولة كينيا، حيث قامت بريطانيا بضمها إلى كينيا..

كان مؤتمر “برلين” 1884-1885 م بداية للوجود الأجنبي الفعلي؛ ليس في القرن الإفريقي بل في سائر بقاع القارة الإفريقية، واستطاعت المملكة المتحدة أن تشمل أجزاء كبيرة من بلاد الصومال تحت حمايتها، تأمينًا للضفة الأخرى من خليج عدن، الذي كان معبرًا ازدادت أهميته الإستراتيجية عقب حفر قناة السويس.

وقد أخذت مقاومة أهل أرض الصومال أشكالا متعددة، منذ الاشتباك الأول للبريطانيين مع أهالي مدينة “بربرة”، وتوقيع المعاهدة الأولى، التي حددت نمطًا من المعاهدات والاتفاقيات، مرورًا بحركة (الدراويش) بقيادة “محمد بن عبد الله حسن”، وصولًا للمطالبة السياسية النامية بتسريع إجراءات نقل السلطة للوطنيين الصوماليين عقب الحرب العالمية الثانية.

كان البدء مع قدوم قوافل الاحتلال البريطاني لجمهورية أرض الصومال. وقد هاجمت قوات الاحتلال البريطاني سنة 1904 قوات الدراويش التابعة للزعيم الصومالي "سيد محمد بن عبد الله" الذي كان يلقبه البريطانيون بـ"الملا المجنون"، وأوقعت إصابات بالغة بين قواته. وقد استمر الملا في محاربة الاستعمار البريطاني للصومال حتى سنة 1920م؛ عندما لجأت بريطانيا إلى الطيران لقصف مواقع الثوار، ثم جاءت وفاة الملا لتضع حدا لثورته الإسلامية.

وفي شهر يونيو من عام 1960 كانت جمهورية أرض الصومال أول الأراضي الصومالية التي تنال استقلالها عن الاستعمار البريطاني، حيث تم رفع أول علم صومالي في مدينة هرجيسا عاصمة أرض الصومال في 26 يونيو عام 1960، وبعدها بخمسة أيام أي في 1 يوليو 1960 حصل جنوب الصومال على استقلاله عن الاستعمار الإيطالي.[33][34]

الاستقلال والوحدة

ومحاولة لتحقيق الحلم الذي كان يراود أبناء أرض الصومال لوحدة الأجزاء الخمسة للقومية الصومالية لتكوين جمهورية الصومال الكبرى في القرن الأفريقي، قام صانعو القرار في جمهورية أرض الصومال بزيارة لإخوانهم في الجنوبى الصومالي لعرض فكرة وحدة الشطرين الشمالي والجنوبي للبلاد من أجل المواصلة لتحرير باقي أجزاء الأراضي الصومالية الكبري وتحقيق الحلم الكبير. ورغم الشروط التعجيزية التي وضعها الإخوة في الجنوب لقبول الوحدة مثل أن تكون لأهل الجنوب الرئاسة ورئاسة الوزراء, ورئاسة مجلس النواب وكذلك الحقائب المهمة في مجلس الوزراء؛ إلا أن صانعو القرار في جمهورية أرض الصومال وافقوا على كل الشروط كما هي مردّدين مقولة شهيرة في تاريخ الصومال الحديث: ”نحن هنا من أجل الوحدة بدون قيد أو شرط”، وقاموا بتسليم السلطة للإخوة في صوماليا، وتنازلوا عن مناصبهم جميعا، وتم الإعلان عما كان يسمي بوحدة الشطري الجنوبي والشمالي للصومال في 1 يونيو/حزيران 1960م باسم جمهورية الصومال.[35]

في بداية عام 1961م؛ أي بعد الاستقلال والوحدة بأقل من عام؛ زاد شعور شعب أرض الصومال بأن الإخوة في الجنوب ليسوا جادين فيما يتعلق بالصومال الكبرى، وأنهم ارتكبوا خطأ كبيرا عندما سلموا دولتهم لهم. واستقال جميع ممثلي أرض الصومال في مجلس النواب استقالة جماعية بعد أن اكتشفوا أن الحلم الذي كان يراودهم؛ والذي ضحوا بدولتهم وسيادتهم من أجله حلم عسير المخاض، وأن تأسيس دولة الصومال الكبرى لن يتحقق ما لم يكن هدفا لكل القومية الصومالية. وفي نفس الفترة حاول عدد من ضباط الجيش المنتمين لإقليم أرض الصومال القيام بمحاولة انقلاب فاشلة كان هدفها إعادة سيادتهم.[36]

استمر الوضع على ما كان عليه إلى أن قام الجيش بانقلاب الحكومة المدنية في عام 1969م بقيادة عميد الجيش محمد سياد بري، وهو من أبناء الجنوب. وتوقع أهالي أرض الصومال أن يكون هذا التغيير استهلالة لتصحيح الوضع، وأن يكون الجيش نصرة لحقوقهم المسلوبة. ألا أن مرور الأيام والسنوات لم يصحبه تغير في الأوضاع المختلفة، وبخاصة المشاريع التنموية التي كان 90% منها يذهب للشطر الجنوبي.[36]

في السبعينات من القرن العشرين كان الجيش الصومالي يعتبر أقوى الجيوش الأفريقية (الثالث من حيث العدد والعدّة) بعد مصر ونيجيريا. وفي عام 1977 شن الجيش الصومالي حربا على إثيوبيا، وحقق انتصارا كبيرا سيطر؛ حيث خلال فترة وجيزة على كل أجزاء القوميات الصومالية التي احتلتها إثيوبيا؛ إلى أن تدخلت القوى الدولية الكبرى حينها (الاتحاد السوفيتي وبمباركة أمريكية)، وطردت الجيوش الصومالية إلى الحدود المعترفة بها دوليا، ومن هنا بدأ انهيار دولة الصومال.[36]

هنا بدأ واضحا أن فكرة الصومال الكبرى باءت بالفشل، وأن هذا الحلم الكبير لن يتحقق ما لم يكن هدفا قوميا تكافح من أجله كل القوميات الصومالية. وفي نفس الفترة حصلت جيبوتي على استقلالها عن الاستعمار الفرنسي باسم جمهورية جيبوتي، وقرر أهلها عدم الانضمام إلى الدولة الصومالية؛ متأثرين في قرارهم بما حصل لجيرانهم أرض الصومال الذين خسروا سيادتهم من أجل هدف يواجه هذا القدر من الصعوبات.

لهذه العوامل، قرر أهالي أرض الصومال المطالبة بحقوهم السيادية، وفتحوا باب المفاوضات مع الجنوبيين الذين كانو يسيطرون على الحكم بواسطة المؤسسة العسكرية التي يرأسها الرئيس محمد سياد بري الذي أصبح فيما بعد واحدا من أكبر دكتاتوريي القارة السمراء. فالحكومات التي تناوبت علي الحكم (المدنية منها والعسكرية) لم يولوا إقليم أرض الصومال العناية اللازمة من احتياجاته من المشاريع التنموية التي تمت في البلاد عقب الاستقلال؛ حيث لم تحصل أرض الصومال سوى على 5% فقط من المشاريع التنموية خلال هذه الفترة التي كانت قد بلغت 20 عاما. وكانت هذه النسبة متمثلة في مصنع الأسمنت في بربرة، والذي اشتغل بطاقة إنتاجية محدودة، بالإضافة إلى عدد قليل من الطرق بين المدن الرئيسية.

ولم يلق مبعوثو أرض الصومال أذنا واعية، بل كان رد الحكومة في حينها البدء في مشروع هدفه تخويف وترهيب أهل أرض الصومال، وقام النظام بقتل وحبس العديد من القيادات العسكرية والسياسية ورجال الأعمال وأساتذة الجامعات في حملة اعتقالات سياسية واسعة النطاق شملت كل من ينتمي إلى القبائل الرئيسية في أرض الصومال، وبلغ الأمر حد وضع مخطط لتهجير أو إبادة القبيلة الرئيسية في أرض الصومال وهي قبيلة ”اسحاق” التي تمثل %70 من سكان المنطقة.

الانفصال

وفي شهر أبريل من عام 1981، اجتمع عدد من السياسيين المنتمين لأرض الصومال في لندن وأسسوا حركة تحرير أرض الصومال، وهي حركة سياسية عسكرية تناضل من أجل تحرير أراضيها من الديكتاتور محمد سياد بري، وإعادة السيادة لأهل أرض الصومال. واتخدت الحركة من العاصمة البريطانية لندن مقرا سياسيا لها، كما اتخذت من الأراضي الصومالية في شرق إثيوبيا مقرا عسكريا لها. وخلال أقل من سنتين بدأت الحركة في تحقيق مكاسب سياسية وانتصارات عسكرية علي نظام محمد سياد بري؛ إلى أن قامت في عام 1988م بهجومها الكاسح على النظام العسكري في المدن الرئيسية بإقليم أرض الصومال في حرب استمرت قرابة العامين؛ نجحت إثرها في تحرير أراضي إقليم أرض الصومال بالكامل من نظام محمد سياد بري، مما أدى إلى انهيار الحكومة المركزية في مقديشو في بداية عام 1991م.

بعد أن تمكنت الحركة من تحرير أراضيها قامت بتنظيم موْتمر في مدينة برعو، وهو المؤتمر الدي عرف باسم “مؤتمر برعو للمصالحة وتقرير المصير”؛ وذلك بمشاركة قيادات الحركة التحريرية, وزعماء وشيوخ القبائل, والسياسيين, ورجال الفكر، وممثلون من كافة شرائح المجتمع. وتم خلال هذا المؤتمر مناقشة كل وجهات النظر الحاضرة في الموْتمر بصدد مستقبل الإقليم، وانتهى الاجتماع باتفاق الجميع على الإعلان عن استعادة الاستقلال وقيام جمهورية أرض الصومال في 18 مايو 1991م علي حدودها المعترف بها عام1960م، كما كتبت مسودة الدستور المؤقت للبلاد الذي كان من أهم بنوده عودة سيادة أرض الصومال، وترك الحكم لحركة تحرير أرض الصومال لفترة مدتها سنتين؛ يتم خلالها وضع الدستور، واستكمال عملية المصالحة لتشمل البلاد عموما. وتم انتخاب رئيس الحركة حينها السفير عبد الرحمن أحمد علي ليكون أول رئيس لجمهورية أرض الصومال، وانتخب حسن عيسي جامع نائبا له للفترة الانتقالية.

ورغم وجود بعض العقبات في الفترة الانتقالية، إلا أنها مرت بنجاح، وقامت الحركة بتسليم السلطة لمجلس الشيوخ وهو مجلس مكون من زعماء القبائل الذين يملكون صلاحيات واسعة وهيبة كبيرة داخل المجتمع، وكان ذلك في مؤتمر بورما في عام 1993م. وخلال هذا المؤتمر الذي حظي بحضور كبير من أصحاب الشأن، صدر البيان الختامي الذي أكد فيه قيادات التكوينات الاجتماعية والسياسية التمسك بسيادة جمهورية أرض الصومال علي حدودها المعترف بها دوليا قبل عام 1960م. وتم في هذا الموْتمر انتخاب السياسي المخضرم محمد حاجي إبراهيم عقال رئيسا والعميد عبد الرحمن شيخ علي نائبا للرئيس، كما تمت تسمية أعضاء مجلسي النواب والشيوخ وعددهم 164 عضوا؛ نصفهم يمثل مجلس الشيوخ والنصف الآخر يمثل مجلس النواب. وكان أهم الأعمال الموكلة للحكومة الجديدة إنجاز المسودة النهائية للدستور الرسمي للبلاد وعرضه علي الشعب للاستفتاء, واستكمال عملية نزع السلاح من الميليشيات القبلية، وتأسيس مؤسسات أمنية وعسكرية لفرض النظام وحماية البلاد.

وفي عام 1997، تم انتخاب الرئيس محمد حاجي إبراهيم عجال رئيسا لفترة ثانية لكي يستمر في استكمال أعمال بناء الدولة التي بدأها، وانتخب طاهر ريالي كاهن نائبا له لفترة 4 سنوات. وفي عام 2000م، أجري الاستفتاء علي الدستور الجديد للبلاد، وقام ما يزيد عن %97 من المشاركين في الاستفتاء بالتصويت لصالح الدستور؛ مما أكد أن المطالبة باستقلال أرض الصومال يعد خيارا شعبيا وليس خيارا نخبويا أو عفويا.[37]

واستمرت عملية بناء الدولة، وقام نظام تعددية حزبية تنافس فيه الأحزاب السياسية المختلفة على الحكم في انتخابات عامة. ونجحت ثلاثة أحزاب في اجتياز شروط الأحزاب الوطنية التي نص عليها الدستور، وهم (حزب اتحاد الأمة – أدوب) برئاسة الرئيس محمد حاجي إبراهيم عجال، و(حزب التضامن للتنمية – كولميي) برئاسة أحمد محمد سيلانيو، و(وحزب العدالة – أعيد) برئاسة السياسي الجديد في الساحة السياسية فيصل علي حسين.[37]

وفي عام 2002 توفي الرئيس محمد حاجي إبراهيم عجال أثناء رحلة علاج في جنوب أفريقيا. ورغم مرارة الخبر المتمثل معنويا في وفاة رجل اعتبره شعب أرض الصومال الموْسس والأب الروحي للبلد؛ إلا أن ذلك لم يعرقل مسيرة تكريس الديمقراطية في البلد الوليد. وعقب فترة قصيرة، أعلن مجلس الشيوخ برئاسة الشيخ إبراهيم شيخ مطر انتخاب نائبه طاهر ريالي كاهن؛ رئيسا للبلاد لتكملة الفترة الانتقالية، واختير عضو مجلس النواب آنذاك أحمد يوسف ياسين نائبا للرئيس في انتقال سلس ودستوري للسلطة.[37]

في عام 2003، أجريت أول انتخابات رئاسية في أرض الصومال، تنافس فيها رئساء الأحزاب الثلاثة، وأسفرت عن فوز حزب اتحاد الأمة –أدوب – بقيادة الرئيس طاهر ريالي كاهن ونائبه أحمد يوسف ياسين بفارق بسيط لا يتعدى الثمانون صوتا عن السياسي البارز أحمد محمد سيلانيو. ورغم هذا الفارق البسيط في النتيجة إلا أن جميع الأحزاب رحبت بالنتيجة المعلنة من لجنة الانتخابات.[37]

بعد ذلك بسنتين أي في عام 2005، حان موعد انتخاب مجلس النواب المكوّن من 82 مقعدا، والتي تنافس فيها 246 مرشحا عن الأحزاب الثلاثة. وانتهت هذه الانتخابات بفوز حزبي المعارضة بثلثي الأصواتن بينما حصل الحزب الحاكم على ثلث أصوات الناخبين؛ مما أعطى أحزاب المعارضة الحق في رئاسة مجلس النواب، وانتخب عبد الرحمن عيرو من حزب العدالة رئيسا لمجلس النواب والأستاذ عبد العزيز سمالي من حزب التضامن نائبا له.[37]

واستمرت مسيرة التقدم في البلاد رغم كل المعوقات الاقتصادية التي واجهتها في هذه الفترة، وكان أهمها مقاطعة دول الخليج للمواشي القادمة من القرن الأفريقي، والظروف الأخرى المحيطة من حروب تدور في جنوب الصومال وقراصنة البحار. ومع كل ذلك، تمكنت أرض الصومال من أن تحافظ علي أمنها واستقرارها، وأن تكمل مسيرة بناء دولة عصرية تعتمد على المؤسسات المنتخبة ديمقراطيا من قبل شعبها.[37]

وفي شهر يونيو من عام 2010، أجريت ثاني انتخابات رئاسية للبلاد، تنافس فيها الأحزاب الثلاثة، وتمكن السياسي أحمد محمد محمود سيلانيو ونائبه عبد الرحمن زيلعي من الفوز برئاسة البلاد لفترة خمسة سنوات، وتم تنصيبه رئيسا للبلاد في يوليو من نفس العام. ولأول مرة حضر حفل تنصيب الرئيس وفود رفيعة المستوى تمثل دور الجوار، بالإضافة إلى ممثلين عن الاتحاد الأوروبي والولايات المتحدة ودول أفريقية عديدة.[37]

الحكومة والسياسة

الدستور

يحدد دستور أرض الصومال النظام السياسي؛ جمهورية أرض الصومال هي دولة مركزية وجمهورية رئاسية، تقوم على السلام والتعاون والديمقراطية ونظام التعددية الحزبية.[38]

الرئيس ومجلس الوزراء

يقود السلطة التنفيذية رئيس مُنتخب، وتضم حكومته نائب الرئيس ومجلس الوزراء.[39] يُرشح أعضاء مجلس الوزراء، المسؤول عن سير العمل الحكومي بشكل طبيعي، من قبل الرئيس ويعتمدهم مجلس النواب (البرلمان).[40] يجب على الرئيس الموافقة على مشاريع القوانين التي أقرها البرلمان قبل أن تدخل حيز التنفيذ.[39] تُعتمد الانتخابات الرئاسية من قبل اللجنة الانتخابية الوطنية لأرض الصومال.[41] يمكن للرئيس أن يشغل منصبه لفترتين رئاسيتين كحد أقصى، مدة كل منهما خمس سنوات. يقع المقر الرسمي والإدارة الرئيسية للرئيس في القصر الرئاسي (أو دار الدولة) في العاصمة هرگيسة.[42][43][44]

البرلمان

Legislative power is held by the Parliament, which is bicameral. Its upper house is the House of Elders, chaired by Suleiman Mohamoud Adan, and the lower house is the House of Representatives,[39] chaired by Yasin Haji Mohamoud.[45] Each house has 82 members. Members of the House of Elders are elected indirectly by local communities for six-year terms. The House of Elders shares power in passing laws with the House of Representatives, and also has the role of solving internal conflicts, and exclusive power to extend the terms of the President and representatives under circumstances that make an election impossible. Members of the House of Representatives are directly elected by the people for five-year terms. The House of Representatives shares voting power with the House of Elders, though it can pass a law that the House of Elders rejects if it votes for the law by a two-thirds majority, and has absolute power in financial matters and confirmation of Presidential appointments (except for the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court).[46]

القانون

The judicial system is divided into district courts (which deal with matters of family law and succession, lawsuits for amounts up to 3 million SLSH, criminal cases punishable by up to 3 years' imprisonment or 3 million SL fines, and crimes committed by juveniles), regional courts (which deal with lawsuits and criminal cases not within the jurisdiction of district courts, labour and employment claims, and local government elections), regional appeals courts (which deal with all appeals from the district and regional courts), and the Supreme court (which deals with issues between courts and in government, and reviews its own decisions), which is the highest court and also functions as the Constitutional Court.[47]

Somaliland nationality law defines who is a Somaliland citizen,[48] as well as the procedures by which one may be naturalised into Somaliland citizenship or renounce it.[49]

The Somaliland government continues to apply the 1962 penal code of the Somali Republic. As such, homosexual acts are illegal in the territory.[50]

الأحزاب والانتخابات

ووفقاً لدستور ارض الصومال لا يمكن وجود أكثر من ثلاثة أحزاب في آن واحد.

- الحزب الديمقراطي الشعبي المتحد (UDUB)

- حزب العدالة والتنمية (UCID)

- حزب التضامن (Kulmiye)

اكتسبت أكبر ثلاث أحزاب هذا الحق في الانتخابات البلدية سنة 2002. وخاضت ثلاثة أحزاب أخرى الانتخابات البلدية التي عقدت في 22 ديسمبر 2002. وفاز الحزب الديمقراطي الشعبي المتحد بـ 41 بالمئة من الأصوات؛ بينما فاز حزب كولمية وحزب العدالة والرفاه بـ 19 بالمئة و 11 بالمئة من الأصوات على التوالي.

انتخب عبدالرحمن علي تور عام 1991-1993 وهو أول رئيس لجمهورية ارض الصومال.

انتخب محمد إبراهيم عقّال في سنة 1997 أول رئيس لجمهورية ارض الصومال لولاية مدتها خمس سنوات. وبعد وفاته أصبح طاهر ريالي كاهن رئيسا للجمهورية. وجاءت نتائج الانتخابات الرئاسية الحامية التي جرت في 15 أبريل 2003 متساوية احصائيا بين طاهر ريالي كاهن من حزب الديمقراطي ومنافسه مجاهد أحمد محمد محمود سيلانيو من حزب كولمية (التضامن).

وأعلنت "اللجنة الوطنية للانتخابات" فوز طاهر ريالي كاهن بـ 80 صوتا، مع أن الأرقام التي نشرت أظهرت بوضوح وجود حسابات خاطئة بالنسبة للطرفين. وأصدرت المحكمة العليا لأرض الصومال لاحقا قرارها بفوز كاهن بحصوله على 217 صوتا.

العلاقات الخارجية

الدولة الوحيدة التي اعترفت رسمياً بأرض الصومال هي إسرائيل،[3] كما ترتبط أرض الصومال بعلاقات سياسية مع جارتيها إثيوپيا[51] وجيبوتي،[52] دولة تايوان الغير عضو في الأمم المتحدة،[53][54] بالإضافة إلى جنوب أفريقيا،[51] السويد،[55] والمملكة المتحدة.[56] في 17 يناير 2007، أرسل الاتحاد الأوروپي وفداً للشؤون الخارجية لمناقشة التعاون المستقبلي.[57] كما أرسل الاتحاد الأفريقي وزير خارجية لمناقشة مستقبل الاعتراف الدولي، وفي 29 و30 يناير 2007، صرح الوزيران بأنهما سيناقشان مسألة الاعتراف مع الدول الأعضاء في المنظمة.[58]

في أوائل عام 2006، وجّه البرلمان الويلزي دعوة رسمية إلى حكومة أرض الصومال لحضور الافتتاح الملكي لمبنى البرلمان في كارديف. واعتُبرت هذه الخطوة بمثابة اعتراف من البرلمان الويلزي بشرعية الحكومة الانفصالية. ولم تُدلِ وزارة الخارجية وشؤون الكومنولث بأي تعليق على الدعوة. وتضم ويلز جالية مغتربين صوماليين كبيرة من أرض الصومال.[59]

عام 2007، حضر وفد برئاسة الرئيس كاهن اجتماع رؤساء حكومات الكومنولث في العاصمة الأوغندية كمپالا. ورغم أن أرض الصومال قد تقدمت بطلب للانضمام إلى الكومنولث بصفة مراقب، إلا أن طلبها لا يزال قيد الدراسة.[60]

في 24 سبتمبر 2010، صرح جوني كارسون، مساعد وزير الخارجية للشؤون الأفريقية، بأن الولايات المتحدة ستعدل استراتيجيتها في الصومال وستسعى إلى تعميق الانخراط مع حكومتي أرض الصومال وأرض البنط مع الاستمرار في دعم الحكومة الانتقالية الصومالية.[61] قال كارسون إن الولايات المتحدة سترسل عمال إغاثة ودبلوماسيين إلى أرض الصومال وأرض البنط، وألمح إلى إمكانية تنفيذ مشاريع تنموية مستقبلية. ومع ذلك، أكد كارسون أن الولايات المتحدة لن تعترف رسمياً بأي من المنطقتين.[62]

التقى وزير الشؤون الأفريقية البريطاني آنذاك، هنري بلنگهام عضو البرلمان، بالرئيس سيلانيو رئيس أرض الصومال في نوفمبر 2010 لمناقشة سبل زيادة مشاركة المملكة المتحدة مع أرض الصومال.[63] وقال الرئيس سيلانيو خلال زيارته إلى لندن: "لقد عملنا مع المجتمع الدولي، وقد تفاعل المجتمع الدولي معنا، وقدم لنا المساعدة، وعمل معنا في برامجنا الديمقراطية والتنموية. ونحن سعداء للغاية بالطريقة التي تعامل بها المجتمع الدولي معنا، ولا سيما المملكة المتحدة والولايات المتحدة والدول الأوروپية الأخرى، وجيراننا الذين يواصلون السعي للاعتراف بنا".[64]

حظي اعتراف المملكة المتحدة بأرض الصومال بدعم حزب استقلال المملكة المتحدة، الذي جاء في المركز الثالث في التصويت الشعبي في الانتخابات العامة 2015، رغم فوزه بمقعد واحد فقط في البرلمان. والتقى الزعيم السابق للحزب، نايجل فاراج، مع علي عدن عوالي، رئيس بعثة المملكة المتحدة في أرض الصومال، في اليوم الوطني لأرض الصومال، الموافق 18 مايو 2015، للتعبير عن دعم الحزب لها.[65]

عام 2011، أبرمت أرض الصومال وأرض البنط المجاورة مذكرة تفاهم أمنية مع سيشل. وتماشياً مع إطار اتفاقية سابقة موقعة بين الحكومة الاتحادية الانتقالية وسيشل، تنص المذكرة على "نقل المدانين إلى سجون في أرض الصومال وأرض الصومال".[66]

في 1 يوليو 2020، وقّعت أرض الصومال وتايوان اتفاقية لإنشاء مكاتب تمثيلية لتعزيز التعاون بين البلدين.[67] بدأ التعاون بين الكيانين السياسيين في مجالات التعليم والأمن البحري والطب عام 2009، ودخل الموظفون التايوانيون أرض الصومال في فبراير 2020 للتحضير للمكتب التمثيلي.[68] اعتباراً من عام 2023، تشير وزارة الخارجية التايوانية إلى أرض الصومال كدولة.[30]

في 1 يناير 2024، وُقِّعت مذكرة تفاهم بين إثيوپيا وأرض الصومال، بموجبها ستستأجر إثيوپيا ميناء بربرة على خليج عدن، وشريطاً ساحلياً بطول 20 كيلومترًا على الخليج، لمدة 20 عاماً، مقابل الاعتراف بأرض الصومال كدولة مستقلة وحصة في الخطوط الجوية الإثيوپية. وفي حال الالتزام بهذا الاتفاق، ستصبح إثيوپيا ثاني دولة عضو في الأمم المتحدة تعترف بأرض الصومال.[69][70]

في 26 ديسمبر 2025، أصبحت إسرائيل أول دولة عضو في الأمم المتحدة تعترف رسمياً بجمهورية أرض الصومال كدولة مستقلة ذات سيادة، وذلك بعد أن وقّع البلدان إعلاناً متبادلاً "بروح الاتفاقيات الإبراهيمية". وقد شكرت أرض الصومال إسرائيل وأعربت عن تقديرها لجهودها في مكافحة الإرهاب وتعزيز السلام الإقليمي.[3]

النزاعات الحدودية

Somaliland continues to claim the entire area of the former British Somaliland which gained independence in 1960 in the name of State of Somaliland.[71] It is currently in control of the vast majority of the former State of Somaliland.[72]

Puntland, a federal member state of Somalia, disputes the Harti-inhabited territory in the former British Somaliland protectorate based on kinship. In 1998, the northern Darod clans established the state, and the Dhulbahante and Warsangali clans wholly participated in its foundation.[73][74][75]

The Harti were the second most powerful clan confederation in Somaliland until the 1993 Borama Conference, when they were replaced in importance by the Gadabursi.[76] The Dhulbahante and Warsangali clans established two separate administrations in the early 1990s.[77] First, the former was to hold the Boocame I conference in May 1993, while the later held a conference in Hadaaftimo in September 1992.[78] In both conferences the desire to remain part of Somalia was expressed.

Tensions between Puntland and Somaliland escalated into violence several times between 2002 and 2009. In October 2004, and again in April and October 2007, armed forces of Somaliland and Puntland clashed near the town of Las Anod, the capital of Sool region. In October 2007, Somaliland troops took control of the town.[79] While celebrating Puntland's 11th anniversary on 2 August 2009, Puntland officials vowed to recapture Las Anod. While Somaliland claims independent statehood and therefore "split up" the "old" Somalia, Puntland works for the re-establishment of a united but federal Somali state.[80]

Somaliland forces took control of the town of Las Qorey in eastern Sanaag on 10 July 2008, along with positions 5 km (3 mi) east of the town. The defence forces completed their operations on 9 July 2008 after the Maakhir and Puntland militia in the area left their positions.[81]

In the late 2000s, SSC Movement (Hoggaanka Badbaadada iyo Mideynta SSC), a local unionist group based in Sanaag was formed with the goal to establish its own regional administration (Sool, Sanaag and Cayn, or SSC).[36] This later evolved into Khatumo State, which was established in 2012. The local administration and its constituents does not recognise the Somaliland government's claim to sovereignty or to its territory.[82]

On 20 October 2017 in Aynabo, an agreement was signed with the Somaliland government that stipulated the amendment of Somaliland's constitution and integrating the organisation into the Somaliland government.[83][84] This signalled the end of the organisation even though it was an unpopular event among the Dhulbahante community.[85][83]

العسكرية

The Somaliland Armed Forces are the main military command in Somaliland. Along with the Somaliland Police and all other internal security forces, they are overseen by Somaliland's Ministry of Defence. The current head of Somaliland's Armed Forces is the Minister of Defence, Abdiqani Mohamoud Aateye.[86] Following the declaration of independence, various pre-existing militia affiliated with different clans were absorbed into a centralised military structure. The resultant large military takes up around half of the country's budget, but the action served to help prevent inter-clan violence.[87]

The Somaliland Army consists of twelve divisions equipped primarily with light weaponry, though it is equipped with some howitzers and mobile rocket launchers. Its armoured vehicles and tanks are mostly of Soviet design, though there are some ageing Western vehicles and tanks in its arsenal. The Somaliland Navy (often referred to as a Coast Guard by the Associated Press), despite a crippling lack of equipment and formal training, has apparently had some success at curbing both piracy and illegal fishing within Somaliland waters.[88][89]

حقوق الإنسان

بحسب تقرير منظمة فريدم هاوس لعام 2023، شهدت أرض الصومال تراجعاً مستمراً في الحقوق السياسية والمساحة المدنية. وتواجه الشخصيات العامة والصحفيون ضغوطاً من السلطات. وتتعرض الأقليات القبلية للتهميش الاقتصادي والسياسي، ولا يزال العنف ضد المرأة مشكلة خطيرة.[90]

التقسيمات الإدارية

تنقسم جمهورية أرض الصومال إلى ستة مناطق: أودل، ساحل، مرودي جيح، توجدير، سناج، وصول. بدورها تنقسم المناطق إلى ثمانية مقاطعات.

المناطق والمقاطعات

| خريطة | المناطق | المساحة (كم2) | العاصمة | المقاطعات |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| أودل | 16.294 | بورمة | باكي، بورمة، زيلع، Lughaya | |

| ساحل | 13.930 | بربرة | شيخ، بربرة | |

| مرودي جيح | 17.429 | هرگيسة | قبيلي، هرگيسة، سلحلي، Baligubadle | |

| توجدير | 30.426 | بورعو | أودويني، بوهودلي، بورعو | |

| سناج | 54.231 | عيرقابو | قردق، عيل أفوين، عيرقابو، لاسكوري | |

| صول | 39.240 | لاسعانود | عينبة، لاسعانود، تليح، حدن |

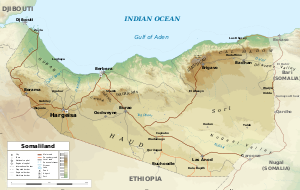

الجغرافيا

الموقع والموئل

Somaliland is situated in the northwest of recognised Somalia. It lies between 08°N and 11°30'N, and between 42°30'E and 49°00'E.[71] It is bordered by Djibouti to the west, Ethiopia to the south, and Somalia to the east. Somaliland has an 850 كيلومتر (528 mi) coastline with the majority lying along the Gulf of Aden.[87] In terms of landmass, Somaliland has an area of 176،120 km2 (68،000 sq mi).[10]

Somaliland's climate is a mixture of wet and dry conditions. The northern part of the region is hilly, and in many places the altitude ranges between 900 و 2،100 متر (3،000 و 6،900 ft) above sea level. The Awdal, Sahil and Maroodi Jeex regions are fertile and mountainous, while Togdheer is mostly semi-desert with little fertile greenery around. The Awdal region is also known for its offshore islands, coral reefs and mangroves.

A scrub-covered, semi-desert plain referred as the Guban lies parallel to the Gulf of Aden littoral. With a width of اثنا عشر كيلومتر (7.5 ميل) in the west to as little as اثنان كيلومتر (1.2 ميل) in the east, the plain is bisected by watercourses that are essentially beds of dry sand except during the rainy seasons. When the rains arrive, the Guban's low bushes and grass clumps transform into lush vegetation.[91] This coastal strip is part of the Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands ecoregion.

Cal Madow is a mountain range in the eastern part of the country. Extending from the northwest of Erigavo to several kilometres west of the city of Bosaso in neighbouring Somalia, it features Somaliland's highest peak, Shimbiris, which sits at an elevation of about 2،416 متر (7،927 ft).[92] The rugged east–west ranges of the Karkaar Mountains also lie to the interior of the Gulf of Aden littoral.[91] In the central regions, the northern mountain ranges give way to shallow plateaus and typically dry watercourses that are referred to locally as the Ogo. The Ogo's western plateau, in turn, gradually merges into the Haud, an important grazing area for livestock.[91] In the east, the Haud is separated from the Ain and Nugal valleys by the Buur Dhaab mountain range.[93]

- Landscapes of Somaliland

View of the Cal Madow Mountains, home to numerous endemic species

Berbera beach

Sacadin, Zeila Archipelago

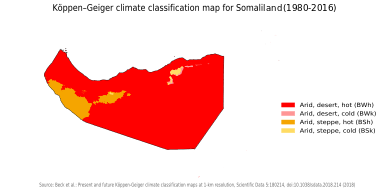

المناخ

Somaliland is located north of the equator. It is semi-arid. The average daily temperatures range from 25 إلى 35 °C (77 إلى 95 °F). The sun passes vertically overhead twice a year, in April and in August or September. Somaliland consists of three main topographic zones: a coastal plain (Guban), the coastal range (Ogo), and a plateau (Hawd). The coastal plain is a zone with high temperatures and low rainfall. Summer temperatures in the region easily average over 100 °F (38 °C). However, temperatures come down during the winter, and both human and livestock populations increase dramatically in the region.

The coastal range (Ogo) is a high plateau to the immediate south of Guban. Its elevation ranges from 6،000 أقدام (1،800 m) above sea level in the West to 7،000 أقدام (2،100 m) in the East. Rainfall is heavier there than in Guban, although it varies considerably within the zone. The plateau (Hawd) region lies to the south of Ogo range. It is generally more heavily populated during the wet season, when surface water is available. It is also an important area for grazing. Somalilanders recognise four seasons in the year; GU and Hagaa comprise spring and summer in that order, and Dayr and Jiilaal correspond to autumn and winter, respectively.[94][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

The average annual rainfall is 446 ميليمتر (17.6 in) in some parts of country according to availability of rain gauge, and most of it comes during Gu and Dayr. Gu, which is the first, or major, rainy season (late March, April, May, and early June), is where Ogo range and Hawd experience the heaviest rainfall. This constitutes the period of fresh grazing and abundant surface water. It is also the breeding season for livestock. Hagaa (from late June through August) is usually dry although there are often some scattered showers in the Ogo range, these are known as Karan rains. Hagaa tends to be hot and windy in most parts of the country. Dayr (September, October, and early November), which roughly corresponds to autumn, is the second, or minor, wet season; the amount of precipitation is generally less than that of Gu. Jilaal, or winter, falls in the coolest and driest months of the year (from late November to early March). It is a season of thirst. Hawd receive virtually no rainfall in winter. The rainfall in the Guban zone, known as "Hays", comes from December to February. The humidity of the country varies from 63% in the dry season to 82% in the wet season.[95]

الحياة البرية

Economy

Somaliland has the fourth-lowest GDP per capita in the world, and there are huge socio-economic challenges for Somaliland, with an unemployment rate between 60 and 70% among youth, if not higher. According to ILO, illiteracy exists up to 70% in several areas of Somaliland, especially among females and the elder population.[96][97]

Since Somaliland is unrecognised, international donors have found it difficult to provide aid. As a result, the government relies mainly upon tax receipts and remittances from the large Somali diaspora, which contribute significantly to the Somaliland economy.[98] Remittances come to Somaliland through money transfer companies, the largest of which is Dahabshiil,[99] one of the few Somali money transfer companies that conform to modern money-transfer regulations. The World Bank estimates that remittances worth approximately US$1 billion reach Somalia annually from émigrés working in the Gulf states, Europe and the United States. Analysts say that Dahabshiil may handle around two-thirds of that figure and as much as half of it reaches Somaliland alone.[100]

Since the late 1990s, service provisions have significantly improved through limited government provisions and contributions from non-governmental organisations, religious groups, the international community (especially the diaspora), and the growing private sector. Local and municipal governments have been developing key public service provisions such as water in Hargeisa and education, electricity, and security in Berbera.[98] In 2009, the Banque pour le Commerce et l'Industrie – Mer Rouge (BCIMR), based in Djibouti, opened a branch in Hargeisa and became the first bank in the country since the 1990 collapse of the Commercial and Savings Bank of Somalia.[101] In 2014, Dahabshil Bank International became the country's first commercial bank.[102] In 2017 Premier Bank from Mogadishu opened a branch in Hargeisa.[103]

Monetary and payment system

The Somaliland shilling, which cannot easily be exchanged outside of Somaliland on account of the nation's lack of recognition, is regulated by the Bank of Somaliland, the central bank, which was established constitutionally in 1994.

The most popular and used payment system in the country is the ZAAD service, which is a mobile money transfer service that was launched in Somaliland in 2009 by the largest mobile operator Telesom.[104][105]

Telecommunications

Telecommunications companies serving Somaliland include Telesom,[106] Somtel, Telcom and NationLink.[107]

The state-run Somaliland National TV is the main national public service television channel, and was launched in 2005. Its radio counterpart is Radio Hargeisa.

Agriculture

Livestock is the backbone of Somaliland's economy. Sheep, camels, and cattle are shipped from the Berbera port and sent to Gulf Arab countries, such as Saudi Arabia.[108] The country is home to some of the largest livestock markets, known in Somali as seylad, in the Horn of Africa, with as many as 10,000 heads of sheep and goats sold daily in the markets of Burao and Yirowe, many of whom shipped to Gulf states via the port of Berbera.[109][110] The markets handle livestock from all over the Horn of Africa.[111]

Agriculture is generally considered to be a potentially successful industry, especially in the production of cereals and horticulture. Mining also has potential, though simple quarrying represents the extent of current operations, despite the presence of diverse quantities of mineral deposits.[112]

The primary method of agricultural production is rain-fed farming. Cereals are the primary crops cultivated. About 70% of the rain-fed agricultural land is used for the main crop, sorghum, while maize occupies another 25% of the land.[113] Scattered marginal lands are also used to grow other crops like barley, millet, groundnuts, beans, and cowpeas. The majority of farms are located near riverbanks, along the banks of streams (togs) and other water sources. The primary methods of channelling water from the source to the farm are floods or crude earth canals that divert perennial water (springs) to the farm. Fruits and vegetables are grown for commercial use on the majority of irrigated farms.[113]

Tourism

The rock art and caves at Laas Geel, situated on the outskirts of Hargeisa, are a popular local tourist attraction. Totalling ten caves, they were discovered by a French archaeological team in 2002 and are believed to date back around 5,000 years. The government and locals keep the cave paintings safe and only a restricted number of tourists are allowed entry.[114] Other notable sights include the Freedom Arch in Hargeisa and the War Memorial in the city centre. Natural attractions are very common around the region. The Naasa Hablood are twin hills located on the outskirts of Hargeisa that Somalis in the region consider to be a majestic natural landmark.[115][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

The Ministry of Tourism has also encouraged travellers to visit historic towns and cities in Somaliland. The historic town of Sheekh is located near Berbera and is home to old British colonial buildings that have remained untouched for over forty years. Berbera also houses historic Ottoman architectural buildings. Another equally famous historic city is Zeila. Zeila was once part of the Ottoman Empire, a dependency of Yemen and Egypt and a major trade city during the 19th century. The city has been visited for its old colonial landmarks, offshore mangroves and coral reefs, towering cliffs, and beach. The nomadic culture of Somaliland has also attracted tourists. Most nomads live in the countryside.[115]

Transport

Bus services operate in Hargeisa, Burao, Gabiley, Berbera and Borama. There are also road transportation services between the major towns and adjacent villages, which are operated by different types of vehicles. Among these are taxis, four-wheel drives, minibuses and light goods vehicles (LGV).[116]

The most prominent airlines serving Somaliland is Daallo Airlines, a Somali-owned private carrier with regular international flights that emerged after Somali Airlines ceased operations. African Express Airways and Ethiopian Airlines also fly from airports in Somaliland to Djibouti City, Addis Ababa, Dubai and Jeddah, and offer flights for the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages via the Egal International Airport in Hargeisa. Other major airports in the region include the Berbera Airport.[117][118]

Ports

In June 2016, the Somaliland government signed an agreement with DP World to manage the strategic port of Berbera with the aim of enhancing productive capacity and acting as an alternative port for landlocked Ethiopia.[119][120]

Oil exploration

In 1958, the first test well was dug by Standard Vacuum (Exxon Mobil and Shell) in Dhagax Shabeel, Saaxil region. These wells were selected without field data or seismic testing and were solely based on the geological makeup of the region. Three of the four test wells were successful in producing of light crude oil.[121]

In August 2012, the Somaliland government awarded Genel Energy a licence to explore oil within its territory. Results of a surface seep study completed early in 2015 confirmed the outstanding potential offered in the SL-10B, SL-13, and Oodweyne blocks, with estimated oil reserves of 1 billion barrels each.[122] Genel Energy is set to drill an exploration well for SL-10B and SL-13 block in Buur-Dhaab, 20 kilometres northwest of Aynaba by the end of 2018.[123] In December 2021, Genel Energy signed a farm-out deal with OPIC Somaliland Corporation, backed by Taiwan's CPC Corporation, on the SL10B/13 block neary Aynaba.[124] According to Genel, the block could contain more than 5 billion barrels of prospective resources.[124] Drilling in SL-10B and SL-13 is scheduled to begin in late 2023, or early 2024 according to Genel.[125]

الديموغرافيا

| السنة | تعداد | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1899 | 246٬000 | — |

| 1960 | 650٬000 | +164.2% |

| 1997 | 2٬000٬000 | +207.7% |

| 2006 | 3٬500٬000 | +75.0% |

| 2013 | 4٬500٬000 | +28.6% |

| 2021 | 5٬700٬000 | +26.7% |

| 2024 | 6٬200٬000 | +8.8% |

| Source: Various[126][127][128][129][7] | ||

There has not been an official census conducted in Somaliland since the Somalia census in 1975, while the results from a 1986 census were never released into public domain.[130] A population estimate was conducted by UNFPA in 2014 primarily for the purpose of distributing United Nations funding among the regions and to offer a reliable population estimate in lieu of a census. This population estimate puts the combined population of the regions of Somaliland at 3.5 million.[131] The Somaliland government estimates that there are 6,200,000 residents as of 2024,[7] an increase from a 2021 government estimate of 5,700,000.[12]

The last British population estimate on the basis of clan in Somaliland occurred before independence in 1960,[132] according to which, out of some 650,000 ethnic Somalis belonging to three major clans residing in the protectorate, the Isaaq, Darod and Dir made up 66%, 19% and 16% of the population, respectively.[133][134]

The largest clan family in Somaliland is the Isaaq,[135] currently making up 80% of Somaliland's population.[136][137][138][139] The populations of the five largest cities in Somaliland – Hargeisa, Burao, Berbera, Erigavo and Gabiley – are predominantly Isaaq.[140][141] The second largest clan is the Gadabursi of the Dir clan[142][143][144] followed by the Harti of the Darod.[145] Other small clans are often not accounted for in such estimates, however, clans including Gabooye, Gahayle, Jibrahil, Magaadle, Fiqishini, and Akisho settle in Somaliland.

Somaliland in addition has an estimated 600,000[146] to a million[147] strong diaspora, mainly residing in Western Europe, the Middle East, North America, and several other African countries.[146][147]

قبائل أرض الصومال

يتكون سكان صوماليلاند من قبيلة إسحاق وقبيلة القدبيرسي أو السمرون قبائل الغبوييي والهرتي الورسنجلي والدولباهنتي.

وتشكل قبيلة إسحاق 70% من سكان جمهورية أرض الصومال تنتشر هذه القبائل في شمال غرب الصومال في إقليم هود وأوجادين وإقليم الصومال في إثيوبيا وجيبوتي يتمحوروا في بعض المدن مثل هرجيسا وعيرجابو وبربرة وبرعو وسيريجابو تعتبر الكتب والمصادر التاريخية التي توثق عنهم نادرة نوعا ما.

تنقسم القبيلة إلى ستة أجذم رئيسية يتم سردها هنا حسب النطق وهي :

- هبر جيعلو : موسى إسحاق (موسيه)، محمد إسحاق (سمرون)، إبراهيم إسحاق (سنبور)، رير دود

- هبر أول : عيسى موسى، سعد موسى [أيوب (أيوب إساق)، أرب (كالي إساق) وقرحاجس (إسماعيل إساق)] عيداجاله، هبر يونس

- تول جيعلي (أحمد إساق)

The Gadabursi subclan of the Dir are the predominant clan of the Awdal region,[148][149] where there is also a sizeable minority of the Issa subclan of the Dir who mainly inhabit the Zeila District.[150]

The Habr Awal subclan of the Isaaq form the majority of the population living in both the northern and western portions of the Maroodi Jeex region, including the cities and towns of northern Hargeisa, Berbera, Gabiley, Madheera, Wajaale, Arabsiyo, Bulhar and Kalabaydh. The Habr Awal also have a strong presence in the Saaxil region as well, principally around the city of Berbera and the town of Sheikh.

The Arap subclan of the Isaaq predominantly live in the southern portion of the Maroodi Jeex region including the capital city of Hargeisa.[151] Additionally, they form the majority of communities living in the Hawd region including Baligubadle.[151] The Arap are also well represented in Sahil and Togdheer regions.[152][153]

The Garhajis subclan of the Isaaq have a sizeable presence among the population inhabiting the southern and eastern portions of Maroodi Jeex region including Southern Hargeisa and Salahlay. The Garhajis are also represented well in western Togdheer region, mainly in Oodweyne and Burao, as well as Sheekh and Berbera in Sahil region. The Garhajis also have a significant presence in the western and central areas of Sanaag region as well, including the regional capital Erigavo as well as Maydh.[154]

The Habr Je'lo subclan of the Isaaq have a large presence in the western parts of Sool, eastern Togdheer region and western Sanaag as well,[155] The Habr Je'lo form a majority of the population living in Burao as well as in the Togdheer region, western Sanaag, including the towns of Garadag, Xiis and Ceel Afweyn and the Aynabo District in Sool. The clan also has a significant presence in the Sahil region, particularly in the towns of Karin and El-Darad, and also inhabit the regional capital Berbera.[156][157][158]

Eastern Sool region residents mainly hail from the Dhulbahante, a subdivision of the Harti confederation of Darod sub-clans, and are concentrated at majority of Sool region districts.[159] The Dhulbahante clans also settle in the Buuhoodle District in the Togdheer region,[160][161] and the southern and eastern parts of Erigavo District in Sanaag.[162]

The Warsangali, another Harti Darod sub-clan, live in the eastern parts of Sanaag, with their population being mainly concentrated in Las Qorey district.[162]

دور القبائل في الانفصال

لا تختلف أرض الصومال في مكونها البشري، وبيئتها القبلية عن باقي بقاع الصومال. لكن الملفت في حالة أرض الصومال وجود توافق داخلي على التعامل الحكيم مع المسألة القبلية التي كانت قد بلغت ذروة تأزمها في ظل النظام الدكتاتوري للرئيس محمد سياد بري، حيث تم تعميق انعدام الثقة وإحياء النعرات القديمة، والتعامل التمييزي ضد أسس الثقافة الصومالية وأبرزها العامل الديني الذي كان يمثل ضمانة حقيقية لتحقيق الامن الداخلي والتماسك الاجتماعيين وبخاصة في الحالات الحرجة التي تعجز النظم القبلية، ومؤسسات الدولة عن معالجتها.[163]

وقد مثل لأداء الحركة الوطنية الصومالية (S.N.M)، ذات الأغلبية من الأكارم من “بني إسحاق”، كأحد المنتصرين في الثورة الشعبية المسلحة على النظام الحاكم، مثل هذا الأداء أحد أهم المنعطفات التاريخية في أرض الصومال والصومال قاطبة، حيث تجلى في خطاب هذه الحركة قدر عال من اعتبار السلام والمصالحة مع الجبهات الأقل قوة، وهي القوى الاجتماعية التي كانت تؤيد النظام الدكتاتوري في المنطقة، منساقة تحت إغراء المكافأة وتضليل الإعلام الحكومي والتلويح بالعقوبة والانتقام، لتساهم في إطالة أمد الحرب الأهلية بالشمال الصومالي، وما ترافق معها من مآسٍ وجرائم حرب وانتهاكات ضد الإنسانية، خارقة القيم الدينية والتقاليد القبلية للصوماليين.[164]

فتوالت مؤتمرات المصالحة كمؤتمر “بورما” في عام 1993م، مبرزة دورًا أساسيًا للقادة التقليديين، كاد أن يتم إلغاؤه في ظل سلطة الفرد الواحد، مجنبة المنطقة تناحرًا طويلًا مؤسفًا وغير مجدٍ، كما جرى لاحقًا في مناطق الجنوب الصومالي، التي خسرت كل نظمها التقليدية بسبب القبضة الحديدية للنظام البائد.[165]

وانتقلت القيادات العسكرية للفصائل القبلية بأرض الصومال من مرحلة القيادة الميدانية إلى الصف الثاني على صعيد عملية صناعة القرار، وتم ذلك بفكر متجرد من النزعة القبائلية الضيقة لصالح نزعة وطنية حرصت على نزع الشرعية عن أي سلوك انفرادي تجاه أي مستجدات قد ترد في جو الاستقلال المشحون بالألم والتوجس. وكان تولي الرئيس محمد حاج إبراهيم عقال مقاليد الحكم في أرض الصومال نقلة للإقليم كله من حيث التحجيم النهائي لقادة الجبهات، خاصة الجبهة الأكبر والأقوى “الحركة الوطنية الصومالية”، مما دفع بقادتها للتوجه التام للدخول في العملية السياسية، بعد القطيعة الحازمة مع مرحلة العمل عبر الفصائل.[5]

وقد لعبت مؤتمرات السلام دورًا أساسيًا، في تهيئة الجو لعودة الطرح الذي طويت صفحته قبل ثلاثة عقود، الهادف لإعلان جمهورية أرض الصومال، ككيان سياسي مستقل عن الوحدة القديمة، وكل ما يحيط به من الكيانات والدول.[166]

Languages

Many people in Somaliland speak at least two of the three national languages: Somali, Arabic and English, although the rate of bilingualism is lower in rural areas. Article 6 of the Constitution of 2001 designates the official language of Somaliland to be Somali,[71] though Arabic is a mandatory subject in school and is used in mosques around the region and English is spoken and taught in schools.[167]

The Somali language is the mother tongue of the Somali people, the nation's most populous ethnic group. It is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family, and its nearest relatives are the Oromo, Afar and Saho languages.[168] Somali is the best documented of the Cushitic languages,[169] with academic studies of it dating from before 1900.

Northern Somali is the main dialect spoken in the country, in contrast to Benadiri Somali which is the main dialect spoken in Somalia.[170]

Cities

قالب:Largest cities of Somaliland

Religion

With few exceptions, Somalis in Somaliland and elsewhere are Muslims, the majority belonging to the Sunni branch of Islam and the Shafi'i school of Islamic jurisprudence.[171] As with southern Somali coastal towns such as Mogadishu and Merca, there is also a presence of Sufism, Islamic mysticism; particularly the Arab Rifa'iya tariiqa.[172] Through the influence of the diaspora from Yemen and the Gulf states, stricter Wahhabism also has a noticeable presence.[173] Though traces of pre-Islamic traditional religion exist in Somaliland, Islam is dominant to the Somali sense of national identity. Many of the Somali social norms come from their religion. For example, most Somali women wear a hijab when they are in public. In addition, religious Somalis abstain from pork and alcohol, and also try to avoid receiving or paying any form of interest (usury). Muslims generally congregate on Friday afternoons for a sermon and group prayer.[174]

Under the Constitution of Somaliland, Islam is the state religion, and no laws may violate the principles of Sharia. The promotion of any religion other than Islam is illegal, and the state promotes Islamic tenets and discourages behaviour contrary to "Islamic morals".[175]

Somaliland has very few Christians. In 1913, during the early part of the colonial era, there were virtually no Christians in the Somali territories, with about 100–200 followers coming from the schools and orphanages of the handful of Catholic missions in the British Somaliland protectorate.[176] The small number of Christians in the region today mostly come from similar Catholic institutions in Aden, Djibouti, and Berbera.[177]

Somaliland falls within the Episcopal Area of the Horn of Africa as part of Somalia, under the Anglican Diocese of Egypt. However, there are no current congregations in the territory.[178] The Roman Catholic Diocese of Mogadishu is designated to serve the area as part of Somalia. However, since 1990 there has been no Bishop of Mogadishu, and the Bishop of Djibouti acts as Apostolic Administrator.[179] The Adventist Mission also indicates that there are no Adventist members.[180]

Health

While 40.5% of households in Somaliland have access to improved water sources, almost a third of households lie at least an hour away from their primary source of drinking water. 1 in 11 children die before their first birthday, and 1 in 9 die before their fifth birthday.[181]

The UNICEF multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS) in 2006 found that 94.8% of women in Somaliland had undergone some form of female genital mutilation;[182] in 2018 the Somaliland government issued a fatwa condemning the two most severe forms of FGM, but no laws are present to punish those responsible for the practice.[182]

Education

Somaliland has an urban literacy rate of 59% and a rural literacy rate of 47%, according to a 2015 World Bank assessment.[183]

Culture

The main clans of Somaliland: Isaaq (Garhajis, Habr Je'lo, Habr Awal, Arap, Ayub), Harti (Dhulbahante, Warsangali, Kaskiqabe, Gahayle), Dir (Gadabuursi, Issa, Magaadle) and Madhiban. Other smaller clans include: Jibraahil, Akisho, and others.

The clan groupings of the Somali people are important social units, and have a central role in Somali culture and politics. Clans are patrilineal and are often divided into sub-clans, sometimes with many sub-divisions.[184]

Somali society is traditionally ethnically endogamous. To extend ties of alliance, marriage is often to another ethnic Somali from a different clan. Thus, for example, a 1954 study observed that in 89 marriages contracted by men of the Dhulbahante clan, 55 (62%) were with women of Dhulbahante sub-clans other than those of their husbands; 30 (33.7%) were with women of surrounding clans of other clan families (Isaaq, 28; Hawiye, 3); and 3 (4.3%) were with women of other clans of the Darod clan family (Majerteen 2, Ogaden 1).[185]

التعليم

الجامعات في جمهورية صوماليلاند المعترف بها من قبل وزارة التربية العليم العالي لعام 2012 هي 17 جامعة رسمية ومعترف بها. وهي:

- جامعة عمود وتعتبر أقدم واكبر جامعة في البلاد , ومقرها اقليم اودل مدينة بوراما (حكومية)

- جامعة هرجيسا، ومقرها العاصمة. (حكومية)

- جامعة برعو، ومقرها اقليم توقدير مدينة بورعو (حكومية)

- جامعة جولس، ومقرها العاصمة وفروع في مدن برعو وبربرة. (خاصة)

- جامعة ادامس، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة الفا، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة نيو جينيريشن، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة ابارسو تيك، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة القرن، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة هوب، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة ادنا ادن الطبية، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة اديس ابابا الطبية، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة بدر كولج، ومقرها العاصمة.(خاصة)

- جامعة سناق، ومقرها منطقة سناج مدينة عيرقابوا (حكومية)

- جامعة أيلو، منطقة ودل مدينة بوراما (خاصة)

- جامعة نوقال، منطقة صول مدينة لاسعانود (حكومية)

- جامعة تماعدي، ومقرها منطقة قبيلي (حكومية)

- جامعة علوم البحار، منطقة ساحل مدينة بربرة (حكومية)

الفنون

Islam and poetry have been described as the twin pillars of Somali culture. Somali poetry is mainly oral, with both male and female poets. They use things that are common in the Somali language as metaphors. Almost all Somalis are Sunni Muslims and Islam is vitally important to the Somali sense of national identity. Most Somalis do not belong to a specific mosque or sect and can pray in any mosque they find.[174]

Celebrations come in the form of religious festivities. Two of the most important are Eid ul-Adha and Eid ul-Fitr, which marks the end of the fasting month. Families get dressed up to visit one another, and money is donated to the poor. Other holidays include 26 June and 18 May, which celebrate British Somaliland's independence and the Somaliland region's establishment, respectively; the latter, however, is not recognised by the international community.[186]

In the nomadic culture, where one's possessions are frequently moved, there is little reason for the plastic arts to be highly developed. Somalis embellish and decorate their woven and wooden milk jugs (haamo; the most decorative jugs are made in Ceerigaabo) as well as wooden headrests.[بحاجة لمصدر] Traditional dance is also important, though mainly as a form of courtship among young people. One such dance known as Ciyaar Soomaali is a local favourite.[187]

An important form of art in Somali culture is henna art. The custom of applying henna dates back to antiquity. During special occasions, a Somali woman's hands and feet are expected to be covered in decorative mendhi. Girls and women usually apply or decorate their hands and feet in henna on festive celebrations like Eid or weddings. The henna designs vary from very simple to highly intricate. Somali designs vary, with some more modern and simple while others are traditional and intricate. Traditionally, only women apply it as body art, as it is considered a feminine custom. Henna is not only applied on the hands and feet but is also used as a dye. Somali men and women alike use henna as a dye to change their hair colour. Women are free to apply henna on their hair as most of the time they are wearing a hijab.[188][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

الرياضة

Popular sports in Somaliland include football, track, field, and basketball.[189][190] Somaliland has a national football team, though it is not a member of FIFA or the Confederation of African Football.[191]

أنظر أيضاً

الهوامش

المصادر

- ^ Name used in The Constitution of the Republic of Somaliland and in Somaliland Official Gazette

- ^ Susan M. Hassig, Zawiah Abdul Latif, Somalia, (Marshall Cavendish: 2007), p.10.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Greyman-Kennard, Danielle (26 December 2025). "Israel, Somaliland establish ties with diplomatic agreement". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 26 December 2025.

- ^ website, Somallilandlaw.com - an independent non-for-profit. "Somaliland Constitution". www.somalilandlaw.com. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ^ Jeffrey, James (23 May 2016). "Somaliland: 25 years as an unrecognised state". Al Jazeera (in الإنجليزية). Al Jazeera Media Network. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ أ ب "Republic of Somaliland – Country Profile 2021" (PDF). March 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت "Somaliland's population reaches 6.2 million". Horn Diplomat. 19 April 2024. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ أ ب "Budget outlook paper for FY2024" (PDF). Somaliland Ministry of Finance Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Stafford, J. H.; Collenette, C. L. (1931). "The Anglo-Italian Somaliland Boundary". The Geographical Journal. 78 (2): 102–121. Bibcode:1931GeogJ..78..102S. doi:10.2307/1784441. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1784441.

- ^ أ ب Lansford, Tom (24 March 2015). Political Handbook of the World 2015 (in الإنجليزية). CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-4833-7155-9.

- ^ "Somaliland's population reaches 6.2 million". Horn Diplomat. 19 April 2024. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ أ ب "Somaliland population reaches 6.2 million, government reports". www.hiiraan.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLewispohoa - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةqGEXu - ^ Ylönen, Aleksi Ylönen (28 December 2023). The Horn Engaging the Gulf Economic Diplomacy and Statecraft in Regional Relations. Bloomsbury. p. 113. ISBN 9780755635191.

- ^ J. A. Suárez (2023). Suárez, J. A. Geopolítica De Lo Desconocido. Una Visión Diferente De La Política Internacional [2023]. p. 227. ISBN 979-8393720292.

- ^ Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-226-46791-7.

- ^ Issa-Salwe, Abdisalam M. (1996). The Collapse of the Somali State: The Impact of the Colonial Legacy. London: Haan Associates. pp. 34–35. ISBN 1-874209-91-X.

- ^ "Somalia". Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^

Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 25 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 378–384.

Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 25 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 378–384. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Salih, Mohamed Abdel Rahim Mohamed; Wohlgemuth, Lennart (1 January 1994). Crisis Management and the Politics of Reconciliation in Somalia: Statements from the Uppsala Forum, 17–19 January 1994. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 9789171063564.

- ^ Kapteijns, Lidwien (18 December 2012). Clan Cleansing in Somalia: The Ruinous Legacy of 1991. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0758-3.

- ^ Richards, Rebecca (24 February 2016). Understanding Statebuilding: Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. ISBN 9781317004660.

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica (2002), p. 835.

- ^ "De Facto Statehood? The Strange Case of Somaliland" (PDF). Journal of International Affairs. Yale University. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ Schoiswohl, Michael (2004). Status and (Human Rights) Obligations of Non-Recognized De Facto Regimes in International Law. University of Michigan: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 351. ISBN 978-90-04-13655-7.

- ^ أ ب Lacey, Marc (5 June 2006). "The Signs Say Somaliland, but the World Says Somalia". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ "Chronology for Issaq in Somalia". Minorities at Risk Project. United Nations Refugee Agency. 2004. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ "Trade office of The FDRE to Somaliland- Hargeysa". mfa.gov.et. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012.

- ^ أ ب Asia West and Africa Department. "Republic of Somaliland". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "UNPO REPRESENTATION: Government of Somaliland". UNPO.org (in الإنجليزية). 1 February 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Norman, Jethro (25 January 2024). "Somaliland at the centre of rising tensions in the Horn of Africa". Danish Institute for International Studies.

- ^ "The dawn of the Somali nation-state in 1960". Buluugleey.com. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ "The making of a Somalia state". Strategy page.com. 9 August 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p.290.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Somaliland's Quest for International Recognition and the HBM-SSC Factor

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Gettleman, Jeffrey (7 March 2007). "Somaliland is an overlooked African success story". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Somaliland Constitution".

- ^ أ ب ت "Somaliland Government". The Somaliland Government. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ "Somaliland Cabinet". The Somaliland Government. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ "Opposition leader elected Somaliland president". AFP. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ "The president of Somaliland is bargaining for recognition". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2025-02-24.

- ^ "The System Worked: Somaliland's 2024 Presidential and Political Party Elections – De facto states research unit". defactostates.ut.ee (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2025-02-24.

- ^ Collins, Gregory Allen (2009). Connected: Developing Somalia's Telecoms Industry in the Wake of State Collapse (in الإنجليزية). University of California, Davis.

- ^ "Somaliland: Speaker of House of Representatives elected". Hiiraan.

- ^ "Somaliland Parliament". Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "Somaliland Judicial System". Retrieved 28 March 2016.d

- ^ Manby, B. (2012). Citizenship Law in Africa: A Comparative Study. Open Society Foundations. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-936133-29-1. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ "Xeerka Jinsiyadda (Xeer Lr. 22/2002)" [Nationality Law (Regulation No. 22/2023)]. Somaliland Law (in الصومالية). 31 May 2001. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Itaborahy, Lucas; Zhu, Jingshu (May 2014). "A world survey of laws: Criminalisation, protection and recognition of same-sex love" (PDF). International Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans and Intersex Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ أ ب "Somaliland closer to recognition by Ethiopia". Afrol News. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ "Somaliland, Djibouti in bitter port feud". Afrol News. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ^ "Outflanked by China in Africa, Taiwan eyes unrecognised Somaliland". Reuters. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Aspinwall, Nick (10 July 2020). "Taiwan Throws a Diplomatic Curveball by Establishing Ties With Somaliland". The Diplomat. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Somaliland Diplomatic Mission in Sweden". Archived from the original on 10 مايو 2009. Retrieved 2 أبريل 2010.

- ^ "Somaliland". United Kingdom Parliament. 4 February 2004. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ "EU Breaks Ice on Financing Somaliland". Global Policy Forum. 11 February 2003. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ "AU supports Somali split". Mail and Guardian. 10 February 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Shipton, Martin (3 March 2006). "Wales strikes out on its own in its recognition of Somaliland". Wales Online. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Somaliland on verge of observer status in the Commonwealth". Qaran News. 16 November 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ Ibrahim, Mohamed; Gettleman, Jeffrey (26 September 2010). "Helicopter Attacks Militant Meeting in Somalia". The New York Times.

- ^ "US near de-facto recognition of Somaliland". Afrol News. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "Strengthening the UK's relationship with Somaliland". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 25 نوفمبر 2010. Archived from the original on 7 أغسطس 2011. Retrieved 29 مارس 2011.

- ^ "Ahmed Mahamoud Silanyo, President of the Republic of Somaliland". This is Africa. 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "UKIP supports Somaliland national day". UKIP. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Report of the Secretary-General on specialized anti-piracy courts in Somalia and other States in the region. UN Security Council. 2012. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/Somalia%20S%202012%2050.pdf. Retrieved on 24 August 2021. - ^ Chiang Yi-ching (1 July 2020). "Taiwan and Somaliland to set up representative offices: MOFA". Focus Taiwan. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Chiang Yi-ching (1 July 2020). "Taiwan and Somaliland to set up representative offices (update)". Focus Taiwan. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Kheyr (1 January 2024). "Somaliland and Ethiopia: Recognition for Sea Access". Somali News in English | The Somali Digest (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Ethiopia's gambit for a port is unsettling a volatile region". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةconst - ^ "BFA Staatendokumentation, Analyse zu Somalia – Lagekarten zur Sicherheitslage. Situation Maps – Security Situation" (in الألمانية). Austria: Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum – via Swedish Migration Agency.

- ^ Lund, Christian; Eilenberg, Michael (4 May 2017). Rule and Rupture: State Formation Through the Production of Property and Citizenship (in الإنجليزية). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-38480-9.

- ^ Höhne, Markus V. "Traditional Authorities in Northern Somalia: Transformation of positions and powers" (PDF). Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology: 16.

- ^ Mesfin, Berouk (September 2009). "The political development of Somaliland and its conflict with Puntland" (PDF). Institute for Security Studies: 10.

- ^ Balthasar, Dominik (2012). State-making in Somalia and Somaliland: Understanding War, Nationalism and State Trajectories as Processes of Institutional and Socio-Cognitive Standardization (PDF) (PhD thesis). London School of Economics and Political Science. p. 179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Hoehne, Markus. "Somaliland: the complicated formation of a de facto state" (PDF). p. 8. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Raadreeb: Midnimada Soomaaliya iyo qodobada shirkii beesha Warsangeli ee 'Hadaaftimo 30 Siteenbar 1992'". Daljir. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Hoehne, Markus V. (7 November 2007). "Puntland and Somaliland clashing in northern Somalia". Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Hoehne, Markus V. (2009). "Mimesis and mimicry in dynamics of state and identity formation in northern Somalia". Africa. 79 (2): 252–281. doi:10.3366/E0001972009000710. S2CID 145753382.

- ^ "Somaliland Defence Forces take control of Las Qorey". Qaran News. 9 July 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ "What is Khatumo State?". Somalia Report. 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ أ ب Mahmood, Omar S. (1 November 2019). "Overlapping Claims by Somaliland and Puntland: The Case of Sool and Sanaag". Africa Portal. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Khaatumo and Somaliland reach final agreement". Somaliland Daily. 21 October 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Doon, Run. "Current Affairs in the Horn of Africa" (PDF). Anglo-Somali Society Journal. Autumn 2017 (Somaliland, Khaatumo agreement reached). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Somaliland President Makes Major Cabinet Changes". Radio Dalsan. 31 March 2020. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ أ ب Mesfin, Berouk (September 2009). "The political development of Somaliland and its conflict with Puntland" (PDF). Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Houreld, Katharine (4 April 2011). "Somaliland coast guard tries to prevent piracy". Navy Times. Gannett Government Media Corporation. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Hussein, Abdi (13 أغسطس 2011). "Somaliland's Military is a Shadow of the Past". Somalia Report. Archived from the original on 20 يناير 2013. Retrieved 27 يناير 2013.

- ^ "Somaliland: Country Profile". Freedom House (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت Hadden, Robert Lee. 2007. "The Geology of Somalia: A Selected Bibliography of Somalian Geology, Geography and Earth Science." Engineer Research and Development Laboratories, Topographic Engineering Center

- ^ "Somalia". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 14 May 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ The South African Geographical Journal: Being a Record of the Proceedings of the South African Geographical Society (in الإنجليزية). 1945. p. 44.

- ^ "SOMALILAND CLIMATE: when to visit". Jouneys by Design (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Somaliland in Figures" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "New World Bank GDP and Poverty Estimates for Somaliland". World Bank.

- ^ "Responses to Information Requests – Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada". Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ أ ب Daniel Harris with Marta Foresti 2011. Somaliland's progress on governance: A case of blending the old and the new Archived 7 أغسطس 2020 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ "Somaliland hope". BBC News. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ "Remittances a lifeline to Somalis". Global Post. 4 July 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "BCIMR Opens First Commercial Bank in Somaliland". Somali Forum – Somalia Online. 4 February 2009.

- ^ "First commercial bank officially opens in Somaliland". 30 November 2014. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015 – via af.reuters.com.

- ^ "Premier Bank Now in Hargeisa Somaliland". All Africa. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Telesom ZAAD: Pushing the mobile money CVA frontier" (PDF). GSM Association. June 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "Send money to Telesom ZAAD mobile money accounts in Somaliland". WorldRemit. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Golis Telecom Somalia Profile". Golis Telecom website. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ "SOMALILAND TELECOMS SECTOR GUIDE BY SOMALILAND BIZ". Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Riches of Somaliland remain untapped". 15 March 2009 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Regulating the Livestock Economy of Somaliland (in الإنجليزية). Academy for Peace and Development. 2002.

- ^ Project, War-torn Societies; Programme, WSP Transition (2005). Rebuilding Somaliland: Issues and Possibilities (in الإنجليزية). Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-228-3.

- ^ A Self-portrait of Somaliland: Rebuilding from the Ruins (in الإنجليزية). Somaliland Centre for Peace and Development. 1999.

- ^ "Country Profile". somalilandgov.com. Government of Somaliland. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ أ ب "Somaliland in Figures 2004" (PDF). Ministry of Planning (Somaliland): 9–10.

- ^ Bakano, Otto (24 April 2011). "Grotto galleries show early Somali life". AFP. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ أ ب "Top Sightseeing – Best Somaliland sightseeing and tourist attractions". Somaliland Travel Agency. 3 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Somaliland's booming informal transport sector: Pitfalls and potentials". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Somaliland's First batch of Hajj pilgrims leave for Mecca". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Egal International Airport HGA". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "DP World Project at Berbera – Somaliland". DP World. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Somaliland secures record $442m foreign investment deal". CNN (in الإنجليزية). 1 August 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Ali, M. Y. (October 2015). "Petroleum Geology and Hydrocarbon Potential of the Guban Basin, Northern Somaliland". Journal of Petroleum Geology. 38 (4): 433–457. Bibcode:2015JPetG..38..433A. doi:10.1111/jpg.12620. S2CID 130266059.

- ^ "Somaliland". Genel Energy. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Onshore Somaliland Mesozoic Rift Play SL10B/13 & Odewayne Licences" (PDF). Genel Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ أ ب Reed, Ed (20 December 2021). "Genel reaches East African farm-out with Taiwan's CPC". Energy Voice. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Ramsay, Peter (15 November 2022). "Genel's Somaliland drilling may slip to 2024". PE Media Network. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ Drake-Brockman, Ralph Evelyn (1912). British Somaliland (in الإنجليزية). Hurst & Blackett. p. 18.

- ^ "Somaliland MDG Report, 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Ambroso, Guido (August 2002). "Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 – 2000" (PDF). UNHCR.

- ^ "Post-Conflict Education Development in Somaliland" (PDF).

- ^ "POPULATION ESTIMATION SURVEY 2014". NBS. Somalia NSB. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "UNFPA Population Estimate" (PDF). UNFPA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "SOMALILAND: DEMOCRATISATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS 28 July 2003" (PDF). International Crisis Group: 2. 2003. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Dominik Balthasar (2012). STATE-MAKING IN SOMALIA AND SOMALILAND Understanding War, Nationalism and State Trajectories as Processes of Institutional and Socio-Cognitive Standardization (PDF) (PhD thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Berouk Mesfin (2009). "The political development of Somaliland and its conflict with Puntland" (PDF). Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Research Directorate, Immigration & Refugee Board, Canada (1 September 1996). "Somaliland: Information on the current situation of the Isaaq clan and on the areas in which they live". Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. SML24647.E. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2015.