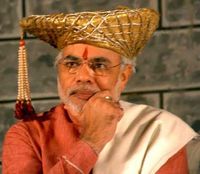

نارندرا مودي

نارندرا مودي | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس وزراء الهند رقم 14 | |

| تولى المنصب 26 مايو 2014 | |

| الرئيس | پراناب موخرجي رام نات كوڤيند |

| سبقه | مانموهان سنغ |

| كبير وزراء گجرات 14 | |

| في المنصب 7 أكتوبر 2001 – 21 مايو 2014 | |

| الحاكم | سوندر سينغ بانداري كايلاشپاتي ميشرا بالرام جاكهار نوال كيشور شارما س.ك. جيمار كاملا بينوال |

| سبقه | كشوباي پاتل |

| خلـَفه | أنانديبن پاتل |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | نارندرا دامودارداس مودي 17 سبتمبر 1950 ڤادناگار، الهند |

| الحزب | حزب بهاراتيا جناتا |

| الزوج | جاشودابه چيمانلال (طفل زواج؛ منفصلان) |

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة دلهي جامعة گجرات |

| التوقيع |  |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

| ||

|---|---|---|

السياسة الوطنية

|

||

نارندرا دامودارداس مودي MP (Hi-NarendraModi.ogg [ˈnəɾendrə dɑmodəɾˈdɑs ˈmodiː]؛ و. 17 سبتمبر 1950)، هو سياسي هندي ورئيس وزراء الهند الحالي ورقم 14 منذ عام 2014. كان رئيس وزراء گجرات من 2001 حتى 2014، وهو عضو برلمان عن دائرة ڤارناساي. مودي عضو في حزب بهارتيا جناتا، والتنظيم الوطني للمتطوعين، تنظيم تطوعي قومي هندوسي. وهو أول رئيس وزراء من خارج المؤتمر الوطني الهندي يفوز بفترتين متتاليتين بأغلبية كاملة، وثاني رئيس وزراء يقضي ولايته الثانية لهم بعد أتال بيهارتي ڤاجپاي.[1]

وُلد مودي لعائلة گجراتية في ڤادناگر، في طفولته كان يساعد والده في بيع الشاي، وفيما بعد أصبح يدير كشكه الخاص. في الثامنة من عمره التحق بالتنظيم الوطني للمتطوعين، ليبدأ ارتباطه الطويل مع هذه المنظمة. ترك مودي مسقط رأسه لينهي دراسته الثانوية ويتزوج جاشودابن تشيمانلال، التي هجرها لاحقاً، ولم يعترف بذلك إلا بعد عقدة عقود. سافر مودي في أرجاء الهند لمدة عامين وزار عدد من المراكز الدينية قبل أن يعود إلى گجرات. عام 1971 أصبح عضواً عاملاً في التنظيم الوطني للمتطوعين. أثناء حالة الطوارئ التي فُرضت في أنحاء البلاد عام 1975، أُجبر مودي على الاختباء. عام 1985 عينته المنظمة لعضوية حزب بهارتيا جناتا، وتقلد عدة مناصب داخل الحزب حتى 2001، ليصبح الأمين العام للحزب.

عام 2001 عُين مودي كبيراً لوزراء گجرات، ويرجع السبب في ذلك للحالة الصحية والصورة العامة الضعيفة لسلفه كشوباي پاتل، في أعقاب زلزال بوج. وسرعان ما أُنتخب مودي عضواً في الجمعية التشريعية. اعتبرت إدارته متواطئة في أحداث شغب گجرات 2002،[أ] أو انتقدت بسبب تعاملها مع الأحداث. لم يجد فريق التحقيق الخاص الذي عينته المحكمة العليا أي دليل لبدء إجراءات الملاحقة القضائية ضد مودي شخصياً.[ب] حظيت سياساته كرئيس للوزراء، والتي كانت تعمل على تشجيع النمو الاقتصادي، بالثناء.[9] انتقدت إدارته لفشلها في تحسين مؤشرات الصحة، الفقر، والتعليم في البلاد.[ت]

قاد مودي حزب بهارتيا جناتا في الانتخابات العامة 2014، التي فاز فيها الحزب بأغلبية في البرلمان الهندي، لوكا سابها، كأول حزب فردي منذ عام 1984. حاولت إدارة مودي رفع الاستثمار الأجنبي المباشر في الاقتصاد الهندي، وقللت من الإنفاق على برامج الرعاية الصحية والرفاع الإجتماعي. حاول مودي تحسين الكفاءة في البيروقراطية؛ وحول السلطة إلى المركزية بإلغاؤه لجنة التخطيط. بدأ حملة صرف صحي كبرى، وأضعف أو ألغى قوانين البيئة والعمل. تُوصف سياساته بهندسة إعادة الإنحياز السياسي تجاه السياسات اليمينية، ويظل مودي شخصية مثيرة للجدل محلياً ودولياً بسبب اعتقاداته القومية الهندوسية ودوره أثناء شغب گگجرات 2002، ويشتشهد به كدليل على أجندة الإقصاء الاجتماعي.[ث]

النشأة

الحياة السياسية المبكرة

In June 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in India which lasted until 1977. During this period, known as "The Emergency", many of her political opponents were jailed and opposition groups were banned.[18][19] Modi was appointed general secretary of the "Gujarat Lok Sangharsh Samiti", an RSS committee coordinating opposition to the Emergency in Gujarat. Shortly afterwards, the RSS was banned.[20] Modi was forced to go underground in Gujarat and frequently travelled in disguise to avoid arrest. He became involved in printing pamphlets opposing the government, sending them to Delhi and organising demonstrations.[21][22] Modi was also involved with creating a network of safe houses for individuals wanted by the government, and in raising funds for political refugees and activists.[23] During this period, Modi wrote a book in Gujarati, Sangharsh Ma Gujarat (In The Struggles of Gujarat), describing events during the Emergency.[24][25] Among the people he met in this role was trade unionist and socialist activist George Fernandes, as well as several other national political figures.[26] In his travels during the Emergency, Modi was often forced to move in disguise, once dressing as a monk, and once as a Sikh.[23]

Modi became an RSS sambhag pracharak (regional organiser) in 1978, overseeing RSS activities in the areas of Surat and Vadodara, and in 1979 he went to work for the RSS in Delhi, where he was put to work researching and writing the RSS's version of the history of the Emergency.[27] He returned to Gujarat a short while later, and was assigned by the RSS to the BJP in 1985.[28] In 1987 Modi helped organise the BJP's campaign in the Ahmedabad municipal election, which the BJP won comfortably; Modi's planning has been described as the reason for that result by biographers.[29] After L. K. Advani became president of the BJP in 1986, the RSS decided to place its members in important positions within the BJP; Modi's work during the Ahmedabad election led to his selection for this role, and Modi was elected organising secretary of the BJP's Gujarat unit later in 1987.[30]

كبير وزراء گجرات

تولي المنصب

In 2001, Keshubhai Patel's health was failing and the BJP lost a few state assembly seats in by-elections. Allegations of abuse of power, corruption and poor administration were made, and Patel's standing had been damaged by his administration's handling of the earthquake in Bhuj in 2001.[31][32][33] The BJP national leadership sought a new candidate for the chief ministership, and Modi, who had expressed misgivings about Patel's administration, was chosen as a replacement.[34] Although BJP leader L. K. Advani did not want to ostracise Patel and was concerned about Modi's lack of experience in government, Modi declined an offer to be Patel's deputy chief minister, telling Advani and Atal Bihari Vajpayee that he was "going to be fully responsible for Gujarat or not at all". On 3 October 2001 he replaced Patel as Chief Minister of Gujarat, with the responsibility of preparing the BJP for the December 2002 elections.[35] Modi was sworn in as Chief Minister on 7 October 2001,[36] and entered the Gujarat state legislature on 24 February 2002 by winning a by-election to the Rajkot – II constituency, defeating Ashwin Mehta of the INC by 14,728 votes.[37]

شغب گجرات 2002

On 27 February 2002, a train with several hundred passengers burned near Godhra, killing approximately 60 people.[ج] The train carried a large number of Hindu pilgrims returning from Ayodhya after a religious ceremony at the site of the demolished Babri Masjid.[40][41] In making a public statement after the incident, Modi declared it a terrorist attack planned and orchestrated by local Muslims.[4][40][42] The next day, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad called for a bandh across the state.[43][44] Riots began during the bandh, and anti-Muslim violence spread through Gujarat.[40][43][44] The government's decision to move the bodies of the train victims from Godhra to Ahmedabad further inflamed the violence.[40][45] The state government stated later that 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus were killed.[46] Independent sources put the death toll at over 2000.[40][47] Approximately 150,000 people were driven to refugee camps.[48] Numerous women and children were among the victims; the violence included mass rapes and mutilations of women.[3]

The government of Gujarat itself is generally considered by scholars to have been complicit in the riots,[2][3][4] and has otherwise received heavy criticism for its handling of the situation.[49] Several scholars have described the violence as a pogrom, while others have called it an example of state terrorism.[50][51][52] Summarising academic views on the subject, Martha Nussbaum said: "There is by now a broad consensus that the Gujarat violence was a form of ethnic cleansing, that in many ways it was premeditated, and that it was carried out with the complicity of the state government and officers of the law."[3] The Modi government imposed a curfew in 26 major cities, issued shoot-at-sight orders and called for the army to patrol the streets, but was unable to prevent the violence from escalating.[43][44] The president of the state unit of the BJP expressed support for the bandh, despite such actions being illegal at the time.[4] State officials later prevented riot victims from leaving the refugee camps, and the camps were often unable to meet the needs of those living there.[53] Muslim victims of the riots were subject to further discrimination when the state government announced that compensation for Muslim victims would be half of that offered to Hindus, although this decision was later reversed after the issue was taken to court.[54] During the riots, police officers often did not intervene in situations where they were able.[3][42][55] In 2012 Maya Kodnani, a minister in Modi's government from 2007 to 2009, was convicted by a lower court for participation in the Naroda Patiya massacre during the 2002 riots.[56][57] Although Modi's government had announced that it would seek the death penalty for Kodnani on appeal, it reversed its decision in 2013.[58][59] On 21 April 2018, the Gujarat High Court acquitted Kodnani while noting that there were several shortfalls in the investigation.[60]

Modi's personal involvement in the 2002 events has continued to be debated. During the riots, Modi said that "What is happening is a chain of action and reaction."[3] Later in 2002, Modi said the way in which he had handled the media was his only regret regarding the episode.[61] In March 2008, the Supreme Court reopened several cases related to the 2002 riots, including that of the Gulbarg Society massacre, and established a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to look into the issue.[49][62][63] In response to a petition from Zakia Jafri (widow of Ehsan Jafri, who was killed in the Gulbarg Society massacre), in April 2009 the court also asked the SIT to investigate the issue of Modi's complicity in the killings.[62] The SIT questioned Modi in March 2010; in May, it presented to the court a report finding no evidence against him.[62][64] In July 2011, the court-appointed amicus curiae Raju Ramachandran submitted his final report to the court. Contrary to the SIT's position, he said that Modi could be prosecuted based on the available evidence.[65][66] The Supreme Court gave the matter to the magistrate's court. The SIT examined Ramachandran's report, and in March 2012 submitted its final report, asking for the case to be closed. Zakia Jaffri filed a protest petition in response. In December 2013 the magistrate's court rejected the protest petition, accepting the SIT's finding that there was no evidence against the chief minister.[67]

انتخابات 2002

الفترة الثانية

المشروعات التنموية

جدل التنمية

السنوات الأخيرة

الانتخابات العامة الهندية

انتخابات 2014

نارندرا مودي يخوض الانتخابات عن دائرتين: دائرة ڤاراناسي في لوك سابها[69] ودائرة ڤادودارا.[70] ترشيحه مدعم من الزعماء الروحيين رامدڤ وموراري باپي،[71] ومن قبل الاقتصاديين جاگديش باگواتي وأرڤيد پاناگريا، الذين أعلنوا أنهم، "...معجبون بسياسات مودي الاقتصادية." [72] ومن منتقدي الاقتصادي حائز جائزة نوبل أمارتيا سـِن، الذي قال أنه لا يريد مودي كرئيس للوزراء لأنه لم يفعل ما يكفي لكي تشغل الأقليات بالأمان، وأن في عهد مودي، كان سجل الصحة والتعليم في الولاية "سيء جداً".[73]

إختار مودي أول عمل أول لقاء تلفزيوني عن الانتخابات القادمة مع هاري شانكار ڤياس على إيه تي ڤي الگجراتية. كان اللقاء بالهندية وجرت ترجمته للغات المحلية حيث كان يذاع على قنوات مجموعة نتورك 18.[74][75]

استطلاعات الرأي

في ثلاث استطلاعات للرأي قدتها وكالات إخبارية ومجلات في مايو 2013، كان نارندرا مودي هو الاختيار الأكثر شعبية لرئيس الوزراء في ابات البرلمانية المقبلة.[76][77][78] في استطلاع C-Voter يقترح أن مودي بكونه مرشح لرئاسة الوزراء، فالتحالف الديمقراطي الوطني يمكنه أن يفوز بزيادة 5% من الأصوات، لتزيد مقاعد التحالف من 179 إلى 220 مقعد، التي لا تزال أقل من الأغلبية ب52 مقعد.[78]

في سبتمبر 2013، نيلسين وذه إكونوميك تايمز نشرت نتائج استطلاع لرأي 100 من قادة الشركات الهندية - 74 منهم أرادو مودي رئيساً للوزراء، مقارنة بسبعة فضلو راهول غاندي.[79][80] معلقاً على الاستطلاعات، العالم السياسي أشوتوش ڤارشني رئيس وزراء بهاراتيا جناتا ليس من المتحمل أن يكون قادراً على عقد تحالفات مع الأحزاب الأخرى، التي لم تكن قادرة على القيام بذلك.[81]

فوزه في الانتخابات

أعلنت النتائج في 16 مايو، قبل 15 يوم من اكتمال الولاية الدستورية للوك سابها الخامس عشر في 31 مايو 2014.[82] تم فرز الأصوات في 989 مركز فرز.[83] التحالف الديمقراطي الوطني، بزعامة حزب بهاراتيا جناتا، فاز بأغلبية ساحقة، ليشغل 336 مقعد. بهاراتيا جناتا بمفرده فاز ب282 مقعد، لتكون المرة الأولى بعد انتصار راجيڤ غاندي في 1984 حيث فاز الحزب بالمقاعد الكافية ليحكم بدون دعم الأحزاب الأخرى.[84] التحالف التقدمي المتحد، بزعامة المؤتمر الوطني الهندي، فاز ب59 مقعد،[85] 44 منها فاز بها المؤتمر.[86][87] وبالتالي فيستعد نارندرا مودي، زعيم بهاراتيا جناتا، لتولي منصبه على رأس أكبر حكومة أغلبية منذ 1984.[88] وهي أيضاً ثاني أسوأ هزيمة لحكومة حالية في تاريخ الهند منذ إستقلالها.

انتخابات 2019

رئاسة الوزراء

الحوكمة ومبادرات أخرى

Modi was sworn in as the Prime Minister of India on 26 May 2014. He became the first Prime Minister born after India's independence from the British Empire.[89] His first year as prime minister saw significant centralisation of power relative to previous administrations.[90][91] Modi's efforts at centralisation have been linked to an increase in the number of senior administration officials resigning their positions.[90] Initially lacking a majority in the Rajya Sabha, or upper house of Indian Parliament, Modi passed a number of ordinances to enact his policies, leading to further centralisation of power.[92] The government also passed a bill increasing the control that it had over the appointment of judges, and reducing that of the judiciary.[12]

سياسته الاقتصادية

The economic policies of Modi's government focused on privatisation and liberalisation of the economy, based on a neoliberal framework.[93][94] Modi liberalised India's foreign direct investment policies, allowing more foreign investment in several industries, including in defence and the railways.[93][95][96] Other proposed reforms included making it harder for workers to form unions and easier for employers to hire and fire them;[94] some of these proposals were dropped after protests.[97] The reforms drew strong opposition from unions: on 2 September 2015, eleven of the country's largest unions went on strike, including one affiliated with the BJP.[94] The Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, a constituent of the Sangh Parivar, stated that the underlying motivation of labour reforms favored corporations over labourers.[93]

The funds dedicated to poverty reduction programmes and social welfare measures were greatly decreased by the Modi administration.[90] The money spent on social programmes declined from 14.6% of GDP during the Congress government to 12.6% during Modi's first year in office.[93] Spending on health and family welfare declined by 15%, and on primary and secondary education by 16%.[93] The budgetary allocation for the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, or the "education for all" programme, declined by 22%.[93] The government also lowered corporate taxes, abolished the wealth tax, increased sales taxes, and reduced customs duties on gold, and jewelry.[93] In October 2014, the Modi government deregulated diesel prices.[98]

In September 2014, Modi introduced the Make in India initiative to encourage foreign companies to manufacture products in India, with the goal of turning the country into a global manufacturing hub.[93][99] Supporters of economic liberalisation supported the initiative, while critics argued it would allow foreign corporations to capture a greater share of the Indian market.[93] Modi's administration passed a land-reform bill that allowed it to acquire private agricultural land without conducting a social impact assessment, and without the consent of the farmers who owned it.[100] The bill was passed via an executive order after it faced opposition in parliament, but was eventually allowed to lapse.[92] Modi's government put in place the Goods and Services Tax, the biggest tax reform in the country since independence. It subsumed around 17 different taxes and became effective from 1 July 2017.[101]

In his first cabinet decision, Modi set up a team to investigate black money.[102] On 9 November 2016, the government demonetised ₹500 and ₹1000 banknotes, with the stated intention of curbing corruption, black money, the use of counterfeit currency, and terrorism.[103] The move led to severe cash shortages,[104][105][106] a steep decline in the Indian stock indices BSE SENSEX and NIFTY 50,[107] and sparked widespread protests throughout the country.[108] Several deaths were linked to the rush to exchange cash.[109][110] In the subsequent year, the number of income tax returns filed for individuals rose by 25%, and the number of digital transactions increased steeply.[111][112]

Over the first four years of Modi's premiership, India's GDP grew at an average rate of 7.23%, higher than the rate of 6.39% under the previous government.[113] The level of income inequality increased,[114] while an internal government report said that in 2017, unemployment had increased to its highest level in 45 years. The loss of jobs was attributed to the 2016 demonetization, and to the effects of the Goods and Services Tax.[115][116]

الصحة والصرف الصحي

In his first year as prime minister, Modi reduced the amount of money spent by the central government on healthcare.[117] The Modi government launched New Health Policy (NHP) in January 2015. The policy did not increase the government's spending on healthcare, instead emphasizing the role of private healthcare organisations. This represented a shift away from the policy of the previous Congress government, which had supported programmes to assist public health goals, including reducing child and maternal mortality rates.[118] The National Health Mission, which included public health programmes targeted at these indices received nearly 20%[119][120] less funds in 2015 than in the previous year. 15 national health programmes, including those aimed at controlling tobacco use and supporting healthcare for the elderly, were merged with the National Health Mission. In its budget for the second year after it took office, the Modi government reduced healthcare spending by 15%.[121] The healthcare budget for the following year rose by 19%. The budget was viewed positively by private insurance providers. Public health experts criticised its emphasis on the role of private healthcare providers, and suggested that it represented a shift away from public health facilities.[122] The healthcare budget rose by 11.5% in 2018; the change included an allocation of 2000 crore for a government-funded health insurance program, and a decrease in the budget of the National Health Mission.[123] The government introduced stricter packaging laws for tobacco which requires 85% of the packet size to be covered by pictorial warnings.[124] An article in the medical journal Lancet stated that the country "might have taken a few steps back in public health" under Modi.[118] In 2018 Modi launched the Ayushman Bharat Yojana, a government health insurance scheme intended to insure 500 million people. 100,000 people had signed up by October 2018.[125]

Modi emphasised his government's efforts at sanitation as a means of ensuring good health.[118] On 2 October 2014, Modi launched the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan ("Clean India") campaign. The stated goals of the campaign included eliminating open defecation and manual scavenging within five years.[126][127] As part of the programme, the Indian government began constructing millions of toilets in rural areas and encouraging people to use them.[128][129][130] The government also announced plans to build new sewage treatment plants.[131] The administration plans to construct 60 million toilets by 2019. The construction projects have faced allegations of corruption, and have faced severe difficulty in getting people to use the toilets constructed for them.[127][128][129] Sanitation cover in the country increased from 38.7% in October 2014 to 84.1% in May 2018; however, usage of the new sanitary facilities lagged behind the government's targets.[132] In 2018, the World Health Organization stated that at least 180,000 diarrhoeal deaths were averted in rural India after the launch of the sanitation effort.[133][134]

الهندوتڤا

During the 2014 election campaign, the BJP sought to identify itself with political leaders known to have opposed Hindu nationalism, including B. R. Ambedkar, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Ram Manohar Lohia.[90] The campaign also saw the use of rhetoric based on Hindutva by BJP leaders in certain states.[135] Communal tensions were played upon especially in Uttar Pradesh and the states of Northeast India.[135] A proposal for the controversial Uniform Civil Code was a part of the BJP's election manifesto.[13]

The activities of a number of Hindu nationalist organisations increased in scope after Modi's election as Prime Minister, sometimes with the support of the government.[90][135] These activities included a Hindu religious conversion programme, a campaign against the alleged Islamic practice of "Love Jihad", and attempts to celebrate Nathuram Godse, the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi, by members of the right wing Hindu Mahasabha.[90] Officials in the government, including the Home Minister, defended the conversion programmes.[135] Modi refused to remove a government minister from her position after a popular outcry resulted from her referring to religious minorities as "bastards."[90] Commentators have suggested, however, that the violence was perpetrated by radical Hindu nationalists to undercut the authority of Modi.[90] Between 2015 and 2018, Human Rights Watch estimated that 44 people, most of them Muslim, were killed by vigilantes; the killings were described by commentators as related to attempts by BJP state governments to ban the slaughter of cows.[136]

Links between the BJP and the RSS grew stronger under Modi. The RSS provided organizational support to the BJP's electoral campaigns, while the Modi administration appointed a number of individuals affiliated with the RSS to prominent government positions.[136] In 2014, Yellapragada Sudershan Rao, who had previously been associated with the RSS, chairperson of the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR).[13] Historians and former members of the ICHR, including those sympathetic to the BJP, questioned his credentials as a historian, and stated that the appointment was part of an agenda of cultural nationalism.[13][137][138]

سياسته الخارجية

Foreign policy played a relatively small role in Modi's election campaign, and did not feature prominently in the BJP's election manifesto.[139] Modi invited all the other leaders of SAARC countries to his swearing in ceremony as prime minister.[140][141] He was the first Indian prime minister to do so.[142]

Modi's foreign policy, similarly to that of the preceding INC government, focused on improving economic ties, security, and regional relations.[139] Modi continued Manmohan Singh's policy of "multi-alignment."[143] The Modi administration tried to attract foreign investment in the Indian economy from several sources, especially in East Asia, with the use of slogans such as "Make in India" and "Digital India".[143] The government also tried to improve relations with Islamic nations in the Middle East, such as Bahrain, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, as well as with Israel.[143]

During the first few months after the election, Modi made trips to a number of different countries to further the goals of his policy, and attended the BRICS, ASEAN, and G20 summits.[139] One of Modi's first visits as prime minister was to Nepal, during which he promised a billion USD in aid.[144] Modi also made several overtures to the United States, including multiple visits to that country.[141] While this was described as an unexpected development, due to the US having previously denied Modi a travel visa over his role during the 2002 Gujarat riots, it was also expected to strengthen diplomatic and trade relations between the two countries.[141]

In 2015, the Indian parliament ratified a land exchange deal with Bangladesh about the India–Bangladesh enclaves, which had been initiated by the government of Manmohan Singh.[92] Modi's administration gave renewed attention to India's "Look East Policy", instituted in 1991. The policy was renamed the "Act East Policy", and involved directing Indian foreign policy towards East Asia and Southeast Asia.[143][145] The government signed agreements to improve land connectivity with Myanmar, through the state of Manipur. This represented a break with India's historic engagement with Myanmar, which prioritised border security over trade.[145]

روسيا

في 24 أغسطس 2021، بحث رئيس الوزراء الهندي نارندرا مودي الوضع في أفغانستان مع الرئيس الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن. وأجرى الزعيمان محادثة هاتفية استمرت نحو 45 دقيقة وناقشا الوضع الراهن في البلاد بعد سيطرة طالبان إلى جانب عدد من القضايا الثنائية. [146]

وغرد مودي على تويتر: "أجرينا تبادلًا مفصلاً ومفيدًا لوجهات النظر مع صديقي الرئيس بوتين حول التطورات الأخيرة في أفغانستان. كما ناقشنا أيضًا قضايا على جدول الأعمال الثنائية، بما في ذلك التعاون الهندي الروسي ضد كوڤيد-19. واتفقنا على مواصلة المشاورات الوثيقة حول القضايا المهمة".

في اليوم السابق، ناقش مودي أيضًا الوضع الأمني في أفغانستان والقضايا الإقليمية مع المستشارة الألمانية أنگلا مركل. كما أكد الزعيمان على أهمية الحفاظ على السلام والأمن خلال هذه الفترة. وبحسب البيان الصادر عن مكتب رئيس الوزراء، اتفق الزعيمان على أن الأولوية الأهم هي عودة الأشخاص المحاصرين في أفغانستان. كما ناقشا القضايا الثنائية، بما في ذلك التعاون في لقاح كورونا، والتعاون الإنمائي مع التركيز على المناخ والطاقة، وتعزيز العلاقات التجارية والاقتصادية.

بعد هذه المحادثة، غرد رئيس الوزراء مودي، "تحدثت إلى المستشارة مركل هذا المساء وناقشنا القضايا الثنائية والمتعددة الأطراف والإقليمية، بما في ذلك التطورات الأخيرة في أفغانستان. كررنا التزامنا بتعزيز الشراكة الاستراتيجية بين الهند وألمانيا".

سياسة الدفاع

India's nominal military spending increased steadily under Modi.[147] The military budget declined over Modi's tenure both as a fraction of GDP and when adjusted for inflation.[148][149] A substantial portion of the military budget was devoted to personnel costs, leading commentators to write that the budget was constraining Indian military modernization.[148][150][149]

The BJP election manifesto had also promised to deal with illegal immigration into India in the Northeast, as well as to be more firm in its handling of insurgent groups. The Modi government issued a notification allowing Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist illegal immigrants from Pakistan and Bangladesh to legalise their residency in India. The government described the measure as being taken for humanitarian reasons but it drew criticism from several Assamese organisations.[151]

The Modi administration negotiated a peace agreement with the largest faction of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCM), which was announced in August 2015. The Naga insurgency in northeast India had begun in the 1950s.[151][152] The NSCM and the government had agreed to a ceasefire in 1997, but a peace accord had not previously been signed.[152] In 2015 the government abrogated a 15-year ceasefire with the Khaplang faction of the NSCM (NSCM-K). The NSCM-K responded with a series of attacks, which killed 18 people.[151] The Modi government carried out a raid across the border with Myanmar as a result, and labelled the NSCM-K a terrorist organisation.[151]

Modi promised to be "tough on Pakistan" during his election campaign, and repeatedly stated that Pakistan was an exporter of terrorism.[153][154][155] On 29 September 2016, the Indian Army stated that it had conducted a surgical strike on terror launchpads in Azad Kashmir. The Indian media claimed that up to 50 terrorists and Pakistani soldiers had been killed in the strike.[156][157][158] Pakistan initially denied that any strikes had taken place.[159] Subsequent reports suggested that Indian claim about the scope of the strike and the number of casualties had been exaggerated, although cross-border strikes had been carried out.[153][160][161] In February 2019 India carried out airstrikes in Pakistan against a supposed terrorist camp. Further military skirmishes followed, including cross-border shelling and the loss of an Indian aircraft.[162][163][164]

سياسته البيئية

آراؤوه

العلمانية

أنا لا أعرف معنى العلمانية. حتى الآن لا أفهمها. بالطبع هناك تعريفها بالقاموس الذي يختلف تماماً عما نراه. مر علينا حينُ كان يُقصد بالعلمانية، ببساطة، الانسجام بين الأديان. ورويداً تغير اللون. فأصبحت العلمانية تعني التشدق بالتعاطف مع الأقليات. ثم رويداً تغير اللون. فأضحت العلمانية هي استرضاء الأقليات. ثم غيرت العلمانية لونها تارة أخرى، لتركـِّز فقط على أصوات المسلمين في الانتخابات، بإسم العلمانية. ثم غيرت العلمانية لونها، فأصبحت كراهية الهندوسية هي العلمانية.

على هذا النمط، فكل خمس سنوات، فإن العلمانية تغير معناها. ولذا فالآن أظن أن من الواجب عليّ أن أحدد بنفسي معنى العلمانية. بالنسبة لي: التنمية تعطي أقوى أساس للعلمانية.[165]

حياته الشخصية والصورة العامة

حياته الشخصية

In accordance with Ghanchi tradition, Modi's marriage was arranged by his parents when he was a child. He was engaged at age 13 to Jashodaben, marrying her when he was 18. They spent little time together and grew apart when Modi began two years of travel, including visits to Hindu ashrams.[34][166] Reportedly, their marriage was never consummated, and he kept it a secret because otherwise he could not have become a 'pracharak' in the puritan Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.[167][168] Modi kept his marriage secret for most of his career. He acknowledged his wife for the first time when he filed his nomination for the 2014 general elections.[169][170] Modi maintains a close relationship with his mother, Hiraben.[171]

A vegetarian and teetotaler,[172][173] Modi has a frugal lifestyle and is a workaholic and introvert.[174] Modi's 31 August 2012 post on Google Hangouts made him the first Indian politician to interact with citizens on a live chat.[175][176] Modi has also been called a fashion-icon for his signature crisply ironed, half-sleeved kurta, as well as for a suit with his name embroidered repeatedly in the pinstripes that he wore during a state visit by US President Barack Obama, which drew public and media attention and criticism.[177][178][179] Modi's personality has been variously described by scholars and biographers as energetic, arrogant, and charismatic.[12][180]

He had published a Gujarati book titled Jyotipunj in 2008, containing profiles of various RSS leaders. The longest was of M. S. Golwalkar, under whose leadership the RSS expanded and whom Modi refers to as Pujniya Shri Guruji ("Guru worthy of worship").[181] According to The Economic Times, his intention was to explain the workings of the RSS to his readers and to reassure RSS members that he remained ideologically aligned with them. Modi authored eight other books, mostly containing short stories for children.[182]

The nomination of Modi for the prime ministership drew attention to his reputation as "one of contemporary India's most controversial and divisive politicians."[183][184][185][186] During the 2014 election campaign the BJP projected an image of Modi as a strong, masculine leader, who would be able to take difficult decisions.[183][187][188][189][190] Campaigns in which he has participated have focused on Modi as an individual, in a manner unusual for the BJP and RSS.[187] Modi has relied upon his reputation as a politician able to bring about economic growth and "development".[191] Nonetheless, his role in the 2002 Gujarat riots continues to attract criticism and controversy.[5] Modi's hardline Hindutva philosophy and the policies adopted by his government continue to draw criticism, and have been seen as evidence of a majoritarian and exclusionary social agenda.[5][187][12][90]

معدلات القبول

جوائز وتكريمات

دولية

| التكريم | البلد | التاريخ | ملاحظات | المصادر | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| وسام الملك عبد العزيز | 3 أبريل 2016 | عضو الطبقة الخاصة، أرفع تكريم مدني في السعودية | [192] | ||

| وسام الأمير غازي أمان الله خان | 4 يونيو 2016 | أرفع تكريم مدني في أفغانسان | [193] | ||

| Grand Collar of the State of Palestine | 10 فبراير 2018 | أرفع تكريم تمنحه دولة فلسطين للأجانب | [194] | ||

| وسام زايد | 4 أبريل 2019 | أرفع تكريم مدني في الإمارات العربية المتحدة. | [195] | ||

| وسام القديس أندرو | 12 أبريل 2019 | أرفع تكريم مدني في روسيا | [196] | ||

الهوامش

- ^ Sources describing Modi's administration as complicit in the 2002 violence.[2][3][4][5][6]

- ^ In 2012, a court stated that investigations had found no evidence against Modi.[7][8]

- ^ Sources stating that Modi has failed to improve human development indices in Gujarat.[5][6]

- ^ Sources discussing the controversy surrounding Modi.[5][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

- ^ The exact number of people killed in the train burning is variously reported. For example, the BBC says it was 59,[38] while The Guardian put the figure at 60.[39]

المصادر

- ^ Malik, Aman (23 May 2019). "Elections 2019: PM Modi returns with bigger mandate, faces growth challenge". VCCircle. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ أ ب Bobbio, Tommaso (2012). "Making Gujarat Vibrant: Hindutva, development and the rise of subnationalism in India". Third World Quarterly. 33 (4): 657–672. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.657423. (يتطلب اشتراك)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Nussbaum, Martha Craven (2008). The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India's Future. Harvard University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-674-03059-6.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Shani, Orrit (2007). Communalism, Caste and Hindu Nationalism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-0-521-68369-2.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Buncombe, Andrew (19 September 2011). "A rebirth dogged by controversy". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJaffrelot2013 - ^ "India Gujarat Chief Minister Modi cleared in riots case". BBC News. BBC. 10 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dasgupta, Manas (10 April 2012). "SIT finds no proof against Modi, says court". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Joseph, Manu (15 February 2012). "Shaking Off the Horror of the Past in India". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Menon, Kalyani Devaki (2012). Everyday Nationalism: Women of the Hindu Right in India. The University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8122-2234-0.

Yet, months after this violent pogrom against Muslims, the Hindu nationalist chief minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi, went to the polls and won a resounding victory

- ^ Mishra, Pankaj (April 2011). Visweswaran, Kamala (ed.). Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4051-0062-5.

The chief minister of Gujarat, a young up-and-coming leader of the Hindu nationalists called Narendra Modi, quoted Isaac Newton to explain the killings of Muslims. "Every action", he said, "has an equal and opposite reaction."

- ^ أ ب ت ث Stepan, Alfred (7 January 2015). "India, Sri Lanka, and the Majoritarian Danger". Journal of Democracy (in الإنجليزية). pp. 128–140. doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0006.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGanguly 2014 - ^ "Indian PM Narendra Modi still mired in controversy, says expert". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nair, Rupam Jain (12 December 2007). "Edgy Indian state election going down to the wire". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Robinson, Simon (11 December 2007). "India's Voters Torn Over Politician". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Burke, Jason (28 March 2010). "Gujarat leader Narendra Modi grilled for 10 hours at massacre inquiry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Guha 2008, p. 493–494.

- ^ Kochanek & Hardgrave 2007, p. 205.

- ^ Marino 2014, pp. 36–40.

- ^ Marino 2014, p. 43.

- ^ Mukhopadhyay 2013, p. 150.

- ^ أ ب Marino 2014, pp. 38–43.

- ^ Patel, Aakar. "The poetic side of Narendra Modi". Deccan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gujarat not enamoured by poet Narendra Modi". The Times of India. 28 June 2004. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Marino 2014, pp. 38–43, 46–50.

- ^ Marino 2014, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Pathak, Anil (2 October 2001). "Modi's meteoric rise". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Marino 2014, pp. 54–57.

- ^ Marino 2014, pp. 56–59.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةVenkatesan Frontline - ^ Phadnis, Aditi (2009). Business Standard Political Profiles of Cabals and Kings. Business Standard Books. pp. 116–21. ISBN 978-81-905735-4-2. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bunsha, Dionne (13 October 2001). "A new oarsman". Frontline. Archived from the original on 28 August 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJose Caravan - ^ "Narendra Modi – Leading the race to 7 RCR". Zee News. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dasgupta, Manas (7 October 2001). "Modi sworn in Gujarat CM amidst fanfare". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Venkatesan, V. "A victory and many pointers". Frontline. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Eleven sentenced to death for India Godhra train blaze". BBC News. 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Burke, Jason (22 February 2011). "Godhra train fire verdict prompts tight security measures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Jaffrelot, Christophe (July 2003). "Communal Riots in Gujarat: The State at Risk?". Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics. doi:10.11588/heidok.00004127. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gujarat riot death toll revealed". BBC News. 11 May 2005. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب Murphy, Eamon (2010). "'We have no orders to save you': state terrorism, politics and communal violence in the Indian state of Gujarat, 2002". In Jackson, Richard; Murphy, Eamon Murphy; Poynting, Scott (eds.). Contemporary State Terrorism. New York, New York, USA: Routledge. pp. 84–103. ISBN 978-0-415-49801-2.

- ^ أ ب ت "Army too helpless as violence mounts". The Economic Times. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت "Curfew imposed in 26 cities". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Decision to bring Godhra victims' bodies taken at top level". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 10 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gujarat Riot Death Toll revealed". BBC News. 11 May 2005. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Campbell, John; Seiple, Chris; Hoover, Dennis R.; et al., eds. (2012). The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Security. Routledge. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-415-66744-9.

- ^ Brass, Paul R. (15 July 2005). The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India. University of Washington Press. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-295-98506-0.

- ^ أ ب Sengupta, Somini (28 April 2009). "Shadows of Violence Cling to Indian Politician". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Ogden, Chris (2012). "A Lasting Legacy: The BJP-led National Democratic Alliance and India's Politics". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 42 (1): 22–38. doi:10.1080/00472336.2012.634639.

- ^ Pandey, Gyanendra (November 2005). Routine violence: nations, fragments, histories. Stanford University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-8047-5264-0.

- ^ Baruah, Bipasha (2012). Women and Property in Urban India. University of British Columbia Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7748-1928-2.

- ^ Hampton, Janie (2002). Internally Displaced People: A Global Survey. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-85383-952-8.

- ^ Christophe, Jaffrelot (2015). "What 'Gujarat Model'?—Growth without Development— and with Socio-Political Polarisation". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 38 (4): 820–838. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1087456.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (25 February 2012). "Gujarat 2002: What Justice for the Victims?". Economic & Political Weekly. 47 (8).

- ^ Soni, Nikunj (21 February 2012). "For Maya Kodnani, riots memories turn her smile into gloom". DNA India. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Maya Kodnani led mob to carry out Naroda riot: Gujarat govt to HC". The Economic Times. 21 February 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Narendra Modi government now rethinks death penalty for ex-aide Maya Kodnani". NDTV. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Modi gets cold feet on death for Kodnani". Hindustan Times. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gujarat HC on Naroda Patiya: SIT probe doesn't 'inspire much confidence'". Press Trust of India. 22 April 2018. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Barry, Ellen (7 أبريل 2014). "Wish for Change Animates Voters in India Election". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 مايو 2014. Retrieved 30 مايو 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت "Timeline: Zakia Jafri vs Modi in 2002 Gujarat riots case". Hindustan Times. 26 December 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "National Human Rights Commission vs. State of Gujarat & Ors. – Writ Petition (Crl.) No. 109/2003". Supreme Court of India. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mahapatra, Dhananjay (3 December 2010). "SIT clears Narendra Modi of willfully allowing post-Godhra riots". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Proceed against Modi for Gujarat riots: amicus". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 9 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dasgupta, Manas (10 May 2012). "SIT rejects amicus curiae's observations against Modi". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Khan, Saeed; Kaushik, Humanshu (26 December 2013). "2002 Gujarat riots: Clean chit to Modi, court rejects Zakia Jafri's plea". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ TNN (20 November 2011). "Farooq praises Modi for work in renewable energy sector — Times Of India". Articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ "It's official: Modi picked for Varanasi, Jaitley for Amritsar - The Times of India". Retrieved 2014-04-04.. Timesofindia.indiatimes.com (2014-03-16). Retrieved on 2014-04-04.

- ^ "Narendra Modi to also contest from Vadodara in Lok Sabha Election". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ Kunwar, D S (27 April 2013). "Sadhus want Narendra Modi declared NDA's PM candidate". The Times of India. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "Academic brawl: Bhagwati-Panagariya pitch for Modi while Amartya Sen backs Nitish". The Economic Times. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAS1 - ^ Narendra Modi in conversation with Hari Shankar Vyas – Video and Full English Transcript

- ^ Narendra Modi picks ETV network for first election interview - Indiantelevision.com

- ^ "Opinion polls: UPA losing ground, Modi's projection as PM candidate will double NDA advantage". Indiatvnews.com. 22 May 2013.

- ^ "Narendra Modi could tilt the scales for BJP with 220 seats – Oneindia News". One India News. 22 May 2013.

- ^ أ ب http://www.firstpost.com/politics/three-polls-one-message-no-alternative-to-modi-for-bjp-804581.html

- ^ "CEO confidence survey: Almost three fourths back Narendra Modi; less than 10% want Rahul Gandhi as PM". The Economic Times. 6 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "India business favours Narendra Modi to be PM: poll". Live Mint. 6 September 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "Doing the Modi math". The Indian Express. 27 June 2013.

- ^ "Terms of Houses, Election Commission of India". Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةIndiatoday - ^ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/lok-sabha-elections-2014/news/Election-results-2014-India-places-its-faith-in-Moditva/articleshow/35224486.cms

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpibgoi - ^ "General Election to Loksabha Trend and Result 2014". Election Commission of India. May 16, 2014. Archived from the original on May 18, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ "Partywise Trends & Result". Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ Modi's Next Moves The Wall Street Journal, May 18, 2014

- ^ "Narendra Modi appointed Prime Minister, swearing in on May 26". The Times of India. 20 May 2014. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Manor, James (2015). "A Precarious Enterprise? Multiple Antagonisms during Year One of the Modi Government". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 38 (4): 736–754. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1083644.

- ^ Wyatt, Andrew (2015). "India in 2014" (PDF). Asian Survey. 55 (1): 33–47. doi:10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33.

- ^ أ ب ت Sen, Ronojoy (2015). "House Matters: The BJP, Modi and Parliament". Journal of South Asian Studies. 38 (4): 776–790. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1091200.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRuparelia - ^ أ ب ت Shah, Alpa; Lerche, Jens (10 October 2015). "India's Democracy: Illusion of Inclusion". Economic & Political Weekly. 50 (41): 33–36.

- ^ "Cabinet approves raising FDI cap in defence to 49 percent, opens up railways". The Times of India. 7 أغسطس 2014. Archived from the original on 7 أغسطس 2015. Retrieved 27 يوليو 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Zhong, Raymond (20 نوفمبر 2014). "Modi Presses Reform for India—But Is it Enough?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 مارس 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Modi renews labour reforms push as jobs regain focus before polls". Economic Times. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Rahul Shrivastava (18 October 2014). "Narendra Modi Government Deregulates Diesel Prices". NDTV. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Look East, Link West, says PM Modi at Make in India launch". Hindustan Times. 25 September 2014. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Guha, Abhijit (2015). "Dangers of Indian Reform of the Colonial Land Acquisition Law". Global Journal of Human-Social Science. 15 (1).

- ^ 3 years of Modi govt: 6 economic policies that have made BJP stronger, harder to defeat, 16 May 2017, Archived from the original on 30 October 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20171030062641/http://m.businesstoday.in/story/from-demonetisation-to-gst-heres-what-pm-modi-did-on-economic-reforms-in-last-3-years-in-office/1/252249.html

- ^ SIT formed to unearth black money – Narendra Modi Cabinet's first decision, 27 May 2014, Archived from the original on 22 December 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20161222203013/http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/SIT-formed-to-unearth-black-money-Narendra-Modi-Cabinets-first-decision/articleshow/35636667.cms, retrieved on 17 February 2017

- ^ "Rs 500, Rs 1000 currency notes stand abolished from midnight: PM Modi". The Indian Express. 9 November 2016. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Demonetisation: Chaos grows, queues get longer at banks, ATMs on weekend". 12 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "India demonetisation: Chaos as ATMs run dry". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Queues get longer at banks, ATMs on weekend". The Hindu. 12 November 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Rukhaiyar, Ashish (9 November 2016). "Sensex crashes 1,689 points on black money crackdown, U.S. election". The Hindu. The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Thousands Protest Across India Against Currency Policy". New York Times. 28 November 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "India: Demonetisation takes its toll on the poor". Al Jazeera. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Demonetisation Death Toll Rises To 25 And It's Only Been 6 Days". huffingtonpost. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ PM Narendra Modi's demonetisation move pays off as income tax net widens, 8 August 2017, Archived from the original on 15 August 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20170815102938/http://www.businesstoday.in/current/policy/narendra-modi-demonetisation-income-tax-returns-arun-jaitley/story/257957.html

- ^ Bhakta, Pratik (27 May 2017), "Demonetisation effect: Digital payments India's new currency; debit card transactions surge to over 1 billion", The Economic Times, Archived from the original on 7 June 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20170607055853/http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/digital-payments-indias-new-currency-debit-card-transactions-surge-to-over-1-billion/articleshow/58863652.cms

- ^ "Budget 2019: Who gave India a higher GDP - Modi or Manmohan?". Business Times. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ V., Harini (14 November 2018). "India's economy is booming. Now comes the hard part". CNBC. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey; Kumar, Hari (31 January 2019). "India's Leader Is Accused of Hiding Unemployment Data Before Vote". New York Times. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Kumar, Manoj; Ghoshal, Devjyot. "Indian jobless rate at multi-decade high, report says, in blow to Modi". Reuters. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEconomist 2015 - ^ أ ب ت Sharma, Dinesh C (May 2015). "India's BJP Government and health: 1 year on". The Lancet. 385 (9982): 2031–2032. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60977-1. PMID 26009217.

- ^ Bagcchi, Sanjeet (2 January 2015). "India cuts health budget by 20%". BMJ. 350. ISSN 1756-1833.

- ^ Karla, Aditya (23 December 2014). "Govt to cut health budget by nearly 20 per cent for 2014-15". www.businesstoday.in. Business Today. Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Budget 2015 disappointed healthcare sector". The Economic Times. 15 March 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mudur, Ganapati (2016). "Rise in India's health budget is "disappointing," say experts". BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online). 352. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Budget 2018 boost for healthcare: Lessons for 'Modicare' from Obamacare - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "85 pc pictorial warning on tobacco products in force from today". Hindustan Times. 1 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ayushman Bharat off to flying start; 1 lakh beneficiaries join Modi's insurance scheme in just 1 month, 22 October 2018, https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/ayushman-bharat-off-to-flying-start-1-lakh-subscribers-join-modis-insurance-scheme-in-just-1-month/1356710/

- ^ Schmidt, Charles W. (November 2014). "Beyond Malnutrition". Environmental Health Perspectives. 122 (11): A298–303. doi:10.1289/ehp.122-a298. PMC 4216152. PMID 25360801.

- ^ أ ب Jeffrey, Robin (2015). "Clean India! Symbols, Policies and Tensions". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 38 (4): 807–819. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1088504.

- ^ أ ب Lakshmi, Rama (14 December 2012). "India is building millions of toilets, but that's the easy part". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب Gahlot, Mandakini (3 أبريل 2015). "India steps up efforts to encourage use of toilets". USA Today. Archived from the original on 16 أغسطس 2017. Retrieved 17 فبراير 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Final Frontier". The Economist. 19 يوليو 2014. Archived from the original on 6 فبراير 2017. Retrieved 17 فبراير 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chaudhary, Archana (18 مايو 2015). "India Plans .3-Billion Sewage Plants in Towns Along the Ganges". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 29 يوليو 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Swachh Bharat full marks for access, usage not upto the mark, 2 October 2018, https://m.timesofindia.com/india/swachh-bharat-full-marks-for-access-usage-not-up-to-the-mark/articleshow/66027457.cms, retrieved on 2 October 2018

- ^ How Swachh Bharat transformed the way public hospitals function, 29 September 2018, https://m.hindustantimes.com/india-news/how-swachh-bharat-transformed-the-way-public-hospitals-function/story-fPgFK331o3JLIPHGcc0GQN.html

- ^ How the Swachh Bharat mission has saved India's kids, 21 September 2018, https://m.hindustantimes.com/india-news/how-the-swachh-bharat-mission-has-saved-india-s-kids/story-G1AjRvhTTTBrv6OUMYq2fO.html

- ^ أ ب ت ث Palshikar, Suhas (2015). "The BJP and Hindu Nationalism: Centrist Politics and Majoritarian Impulses". Journal of South Asian Studies. 38 (4): 719–735. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1089460.

- ^ أ ب "Narendra Modi and the struggle for India's soul". The Economist. 2 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ "Choice of ICHR chief reignites saffronisation debate". The Hindu. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Right-wingers question ICHR chief selection". The Times of India. 18 July 2014. Archived from the original on 21 July 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت Hall, Ian (2015). "Is a 'Modi doctrine' emerging in Indian foreign policy?". Australian Journal of International Affairs. 69 (3): 247–252. doi:10.1080/10357718.2014.1000263.

- ^ Grare, Frederic (Winter 2015). "India–Pakistan Relations: Does Modi Matter?". The Washington Quarterly. 37 (4): 101–114. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2014.1002158.

- ^ أ ب ت Pant, Harsh V. (Fall 2014). "Modi's Unexpected Boost to India-U.S. Relations". The Washington Quarterly. 37 (3): 97–112. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2014.978438.

- ^ Swami, Praveen (22 مايو 2014). "In a first, Modi invites SAARC leaders for his swearing-in". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 25 مايو 2014. Retrieved 24 مايو 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت ث Hall, Ian (2016). "Multialignment and Indian Foreign Policy under Narendra Modi". The Round Table. 105 (3): 271–286. doi:10.1080/00358533.2016.1180760.

- ^ Mocko, Anne; Penjore, Dorji (2015). "Nepal and Bhutan in 2014". Asian Survey. 55 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.75.

- ^ أ ب Downie, Edmund (25 February 2015). "Manipur and India's 'Act East' Policy". The Diplomat.

- ^ "PM Modi talks to Russian President Putin over Afghanistan situation". dnaindia.com. 2021-08-24. Retrieved 2021-08-24.

- ^ Manghat, Sajeet (1 February 2019). "Budget 2019: A 10 Percent Hike in Defence Capital Outlay". Bloomberg Quint. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ أ ب Rajagopalan, Rajeswari Pillai (9 February 2019). "Why India's New Defense Budget Falls Short". The Diplomat. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ أ ب "India spends a fortune on defence and gets poor value for money". The Economist. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Sharma, Kiran (17 February 2019). "India's arms modernization hampered by populist budget". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Singh, Amarjeet (2016). "Narendra Modi and Northeast India: development, insurgency and illegal migration". Journal of Asian Public Policy. 9 (2): 112–127. doi:10.1080/17516234.2016.1165313.

- ^ أ ب Sinha, Amitabh; Swami, Praveen (4 August 2015). "Towards the Govt-Naga peace accord: Everything you need to know". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Reversing roles". The Economist. 6 October 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ "PM slams Pakistan on terror: 10 quotes from Narendra Modi's speech in Kozhikode". The Indian Express. 24 September 2016. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "One nation in South Asia spreading terrorism: PM Modi at G20 Summit". The Times of India. 5 September 2016. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "India's surgical strikes across LoC: Full statement by DGMO Lt Gen Ranbir Singh". Hindustan Times. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Uri avenged: 35–40 terrorists, 9 Pakistani soldiers killed in Indian surgical strikes". 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Surgical strikes in PoK: How Indian para commandos killed 50 terrorists, hit 7 camps". India Today. 29 سبتمبر 2016. Archived from the original on 1 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 1 أكتوبر 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ellen Barry; Salman Masood (29 September 2016). "India Claims 'Surgical Strikes' in Pakistani-Controlled Kashmir". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ M. Ilyas Khan (23 October 2016), "India's 'surgical strikes' in Kashmir: Truth or illusion?", BBC News, Archived from the original on 25 October 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20161025175100/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-37702790, retrieved on 23 October 2016

- ^ "Balakot: Pakistan vows to respond after Indian 'air strikes'". BBC. 26 February 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Joanna Slater and Pamela Constable (27 February 2019), "Pakistan captures Indian pilot after shooting down aircraft, escalating hostilities", Washington Post

- ^ Jeffrey Gettleman; Hari Kumar; Samir Yasir (2 March 2019), "Deadly Shelling Erupts in Kashmir Between India and Pakistan After Pilot Is Freed", The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/02/world/asia/kashmir-shelling-india-pakistan.html

- ^ "Skirmishing between India and Pakistan could escalate". The Economist. 28 February 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Wikiquote: Narendra Modi

- ^ "Narendra Modi's 'wife' Jashodaben finally speaks, 'I like to read about him (Modi) ... I know he will become PM'". The Financial Express. 1 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mukhopadhyay 2013, A time of difference.

- ^ "Narendra Modi: From tea vendor to PM candidate". India Today. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bodh, Anand (17 February 2014). "I am single, so best man to fight graft: Narendra Modi". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Jashodaben is my wife, Narendra Modi admits under oath". The Times of India. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "PM Narendra Modi takes blessings from mother Hiraba on his 66th birthday". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "10 facts to know about Prime Minister Narendra Modi". 23 October 2012. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Harding, Luke (18 August 2013). "Profile: Narendra Modi". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Hawk in Flight". Outlook India. 24 December 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Narendra Modi on Google Hangout, Ajay Devgn to host event". The Times of India. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "People ask, Narendra Modi answers on Google Plus Hangout". CNN-IBN. 1 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sharma, Swati (6 June 2014). "Here's what Narendra Modi's fashion says about his politics". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Friedman, Vanessa (3 June 2014). "Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India: A Leader Who Is What He Wears". The New York Times Runway blog. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Price, Lance (24 March 2015). The Modi Effect: Inside Narendra Modi's campaign to transform India. Quercus. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-1-62365-938-7.

- ^ Marino 2014, pp. 60–70.

- ^ "Narendra Modi on MS Golwalkar, translated by Aakar Patel – Part 1". Caravan. 31 May 2014. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Jyotipunj: Narendra Modi writes on 'my organisation, my leaders'". Economic Times. 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBasu 2014 - ^ Ramaseshan, Radhika (2 July 2013). "Boomerang warning in article on 'polarising' Modi". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Malik, Ashok (8 November 2012). "Popular but polarising: can Narendra Modi be PM?". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bajaj, Vikas (22 ديسمبر 2012). "In India, a Dangerous and Divisive Technocrat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 ديسمبر 2012. Retrieved 15 أغسطس 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJaffrelot 2015 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةChhibber - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةChacko - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSrivastava - ^ "NaMo, Ram the new mantra on Dalal Street!". The Economic Times. 15 سبتمبر 2013. Archived from the original on 11 يناير 2015. Retrieved 16 سبتمبر 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Modi conferred highest Saudi civilian honour". Hindustan Times. 3 April 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "PM Modi conferred Afghanistan's highest civilian honour". Indian Express. 4 June 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Modi conferred 'Grand Collar of the State of Palestine'". The Hindu. 10 February 2018. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

{{cite news}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help) - ^ "PM Modi awarded highest civilian honour Zayed Medal by UAE". India Today. 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Russia awards Narendra Modi its highest order, PM thanks Putin". India Today. 12 April 2019. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

المراجع

- Guha, Ramachandra (2008). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-095858-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kochanek, Stanley; Hardgrave, Robert (2007). India: Government and Politics in a Developing Nation. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-00749-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marino, Andy (2014). Narendra Modi: A Political Biography. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 978-93-5136-218-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mukhopadhyay, Nilanjan (2013). Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times. Westkabd. ASIN B00C4PGOF4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه كشوباي پاتل |

كبير وزراء گجرات 2001–2014 |

تبعه أنانديبن پاتل |

| سبقه مانموهان سنغ |

رئيس وزراء الهند 2014–الحاضر |

الحالي |

| لوك سابها | ||

| سبقه مورلي مانوهار جوشي |

عضو اللوك سابها عن دائرة ڤاراناسي 2014–الحاضر |

الحالي |

- صفحات تحتوي روابط لمحتوى للمشتركين فقط

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: URL

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- مواليد 17 سبتمبر

- مواليد 1950

- شهر الميلاد مختلف في ويكي بيانات

- يوم الميلاد مختلف في ويكي بيانات

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Portal templates with default image

- هندوس هنود

- سياسيون هنود

- أشخاص أحياء

- رؤساء وزراء الهند

- أشخاص من گجرات

- كبار وزراء گجرات

- خريجو جامعة گجرات

- نباتيون هنود

- سياسيو حزب بهاراتيا جناتا

- أشخاص غير مرغوب فيهم

- أشخاص من مقاطعة محسانة

- مرشحو التحالف الديمقراطي الوطني في الانتخابات العامة الهندية 2014