هربرت هوڤر

| هربرت هوڤر Herbert Hoover | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 31 | |

| في المنصب 4 مارس 1929 – 4 مارس 1933 | |

| نائب الرئيس | تشارلز كرتس |

| سبقه | كالڤين كوليدج |

| خلفه | فرانكلين روزڤلت |

| وزير التجارة الأمريكي الثالث | |

| في المنصب 5 مارس 1921 – 21 أغسطس 1928 | |

| الرئيس | وارن هاردنگ كالڤين كوليدج |

| سبقه | جوشوا ألكسندر |

| خلفه | وليام هوايتنگ |

| المرشح الرئاسي الجمهورية 1928 (فاز) | |

| في المنصب 4 يونيو 1928 – 6 نوفمبر 1928 | |

| سبقه | كالڤن كولدج |

| خلفه | هربرت هوڤر (نفسه) |

| المرشح الرئاسي الجمهورية 1932 (خسر) | |

| في المنصب 5 يونيو 1932 – 8 نوفمبر 1932 | |

| سبقه | هربرت هوڤر (نفسه) |

| خلفه | ألف لاندون |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | Herbert Clark Hoover أغسطس 10, 1874 وست برانش، أيوا |

| توفي | أكتوبر 20, 1964 (aged 90) نيويورك، نيويورك |

| القومية | أمريكي |

| الحزب | جمهوري |

| الزوج | Lou Henry (ز. 1899; و. 1944) |

| الأنجال | |

| الجامعة الأم | جامعة ستانفورد |

| المهنة | مهندس (تعدين، مدني)، رجل أعمال، إنساني |

| الدين | كويكر |

| التوقيع | |

Announcing his 1931 economic stimulus plan Recorded October 1931 | |

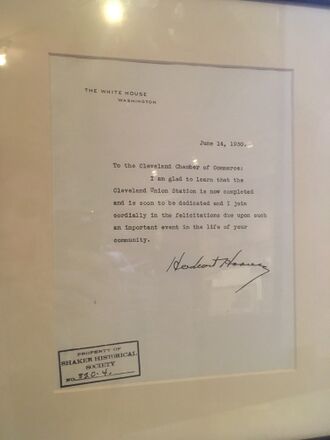

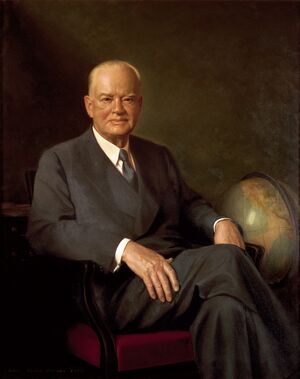

كان هربرت كلارك هوڤر (10 أغسطس 1874 - 20 أكتوبر 1964) الرئيس الحادي و الثلاثون للولايات المتحدة مهندس مناجم ناجح، إدارياً وإنسانياً. مَثَل مكونات حركة التأثير لمناطق التطوير، مجادلاً الحلول التقنية شبه الهندسية لكل المشاكل الإجتماعية و الإقتصادية، الأمر الذي تحداه الكساد الكبير الذي بدأ في رئاسته. A self-made man who became rich as a mining engineer, Hoover led the Commission for Relief in Belgium, served as the director of the U.S. Food Administration, and served as the U.S. Secretary of Commerce.

Hoover was born to a Quaker family in West Branch, Iowa, but he grew up in Oregon. He was one of the first graduates of the new Stanford University in 1895. He took a position with a London-based mining company working in Australia and China. He rapidly became a wealthy mining engineer. In 1914 at the outbreak of World War I, he organized and headed the Commission for Relief in Belgium, an international relief organization that provided food to occupied Belgium. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Hoover to lead the Food Administration. He became famous as his country's "food czar". After the war, Hoover led the American Relief Administration, which provided food to the starving millions in Central and Eastern Europe, especially Russia. Hoover's wartime service made him a favorite of many progressives, and he unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination in the 1920 presidential election.

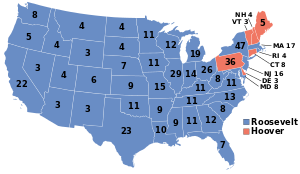

Republican President Warren G. Harding appointed Hoover as Secretary of Commerce in 1920, and he continued to serve under President Calvin Coolidge after Harding died in 1923. Hoover was an unusually active and visible Cabinet member, becoming known as "Secretary of Commerce and Under-Secretary of all other departments". He was influential in the development of air travel and radio. He led the federal response to the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Hoover won the Republican nomination in the 1928 presidential election and defeated Democratic candidate Al Smith in a landslide. In 1929 Hoover assumed the presidency during a period of widespread economic stability. However, during his first year in office, the stock market crashed, signaling the onset of the Great Depression. The Great Depression dominated Hoover's presidency, and he responded by pursuing a series of economic policies in an attempt to lift the economy. Hoover scapegoated Mexicans for the Depression, instituting policies and sponsoring programs of repatriation and deportation to Mexico.

In the midst of the economic crisis, Hoover was decisively defeated by Democratic nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election. Hoover's retirement was over 31 years long, one of the longest presidential retirements. He authored numerous works and became increasingly conservative in retirement. He strongly criticized Roosevelt's foreign policy and New Deal domestic agenda. In the 1940s and 1950s, public opinion of Hoover improved largely due to his service in various assignments for presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower, including chairing the influential Hoover Commission. Critical assessments of his presidency by historians and political scientists generally rank him as a significantly below-average president, although Hoover has received praise for his actions as a humanitarian and public official.[1][2][3]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الخلفية العائلية

وُلد هوڤر لعائلة من الكويكر تنحدر من أصول ألمانية وسويسرية في وست برانش، أيوا، فكان أول رئيس أمريكي يولد غرب نهر الميسيسيبي. توفي كلا والديه بينما كان صغيراً، إذ توفي والده جسي هوفر في 1880 ووالدته هلدا ماينثورن في 1884. في 1885 ذهب هربرت هوفر ابن الحادية عشرة إلى نيوبرگ، أوريگون ليصبح تحت وصاية خاله جون ماينثورن وهو طبيب وصاحب عقارات يتذكره هوڤر كـ "رجل قاسٍ في ظاهر الأمر، لكن ككل الكويكرز لطيف في العمق".

في سن مبكرة كان هوفر معتمداً وطموحاً. "طموح صباي كان أن أكون قادراً على كسب عيشي بنفسي بدون مساعدة من أي كان." كما قال مرة.

كصبي موظف شركة خاله للأراضي أتقن مسك الدفاتر والطباعة بينما ذهب إلى مدرسة أعمال أيضاً في المساء. وبفضل معلمة مدرسة هي الآنسة جين گراي انفتحت عينا الصبي على روايات تشارلز ديكنز والسير والتر سكوت. ديڤد كوپرفيلد قصة صبي آخر يتيم قدم إلى العالم ليعيش بمواهبه الخاصة بقيت المفضلة لدى الصبي طوال حياته.

تعليمه

في خريف 1891 كان هوفر عضواً في الفصل الأول للطلاب في جامعة ليلاند ستانفورد الابن الجديدة في كاليفورنيا. مقضياً وقتاً أكبر خارج الفصل من الوقت داخله، أدار هوفر فرق البيسبول وكرة القدم، بدأ مغسلة، وأدار وكالة محاضرات، متفقاً مع طلاب آخرين من خلفيات أقل ثراء ضد أثرياء الحرم المدللين.

تخصص هوفر في الجيولوجيا و درس مع البروفيسور جون كاسپر برانر الذي حصل له على وظيفة صيفية في رسم خرائط جبال أوزارك في أركنسا وكولورادو. وفي مختبر برانر قابل لو هنري وهي ابنة مصرفي ولدت في واترلو، أيوا في 1874. وكانت لو تشاطر رفيقها من أيوا الطبيعة المستقلة والمنطلقة.

حياته العملية

بعد تخرجه من جامعة ستانفورد في 1895 بدرجة في الجيولوجيا كان هوفر غير قادر على إيجاد وظيفة كمهندس مناجم، لذا عمل كموظف في شركة استشارية بسان فرانسيسكو تخص لويس جانين، وأعجب جانين بهوفر بحيث أنه أوصى به كمهندس ليعمل مع شركة المناجم البريطانية بيويك و مويرينگ ليعمل في أستراليا.

وصل هوفر إلى ألباني في مايو 1897، و أمضى سنة و نصف ينظم خطط تطوير العمل، يرتب و يعد المعدات، و يختبر المناطق الجديدة. حتى أنه كان يذهب إلى المناجم البعيدة على ظهر الجمل الذي دعاه "خلقاً أقل إبداعية من الحصان." و في واحدة من رحلاته عثر على منجم يدعى أبناء گواليا، أوصى شركته بشراءه، ومع الزمن أثبت هذا المنجم أنه واحد من أغنى مناجم الذهب في العالم.

وبعد أقل من عامين في أستراليا عرضت الشركة على هوفر منصباً لتطوير مناجم الفحم في الصين، وبعمل في اليد عرض هوفر الزواج على لو هنري.

سافر هوفر إلى الصين عن طريق الولايات المتحدة، وتزوج لو هنري في غرفة جلوس والديها في كاليفورنيا، ليرزقا فيما بعد بطفلين هما هربرت الابن وألان.

وصل آل هوفر إلى الصين في مارس 1899 وسرعان ما انغمس هربرت في مهمة معقدة لموازنة اهتمامات شركته بتطوير مناجم الفحم و مطالبات الموظفين المحليين بتحديد مصادر جديدة للذهب. ومبكراً في عام 1900 انتشرت موجة من مشاعر معاداة الغرب في الصين، وصممت حركة البوكسرز على تدمير كل الصناعات الغربية ، سكك الحديد، خطوط التلغراف، المنازل، وقتلت المواطنين الغربيين في الصين.

في يونيو 1900 غادر آل هوفر مع أسر أخرى إلى مدينة تيانجين محميين بقليل من الجنود الغربيين، وساعد هوفر في تنظيم الخطوط الدفاعية بينما ساعدت زوجته في المستشفى.

حررت تيانجين في أواخر يوليو وتمكن هربرت و لو هوفر من المغادرة إلى إنجلترا على متن قارب بريد ألماني، و من ثم عادا في 1901 بعد القضاء على الثورة، ليتابع هوفر عمله في بناء الشركة. وبعد أشهر قليلة عرض عليه منصب شريك أصغر في الشركة البريطانية بيويك و مويرينغ، فغادر آل هوفر الصين.

بين عامي 1907 و 1912 جمع هربرت و لو موهبيتهما لإنشاء ترجمة لواحد من الأعمال المبكرة وهو كتاب جورج أگريكولا De re metallica المنشور في 1556 في 670 صفحة.

وبقيت ترجمة هوفر الترجمة التعريفية باللغة الإنجليزية لعمل أگريكولا.

الحرب العالمية الأولى

| أيمن زغلول ساهم بشكل رئيسي في تحرير هذا المقال

|

في عام 1919 وقد وضعت الحرب العالمية الأولي أوزارها ومؤتمر السلام منعقد في باريس بقصر فرساي. وكانت الحرب قد بدأت بغزو ألماني لأراضي بلجيكا حتي تصل منها إلي فرنسا. وبالتالي وقع 7 مليون بلجيكي تحت الحكم الألماني. وهؤلاء كان حالهم عدم حتي أنهم كانوا مهددين بالجوع عقب الحرب مما جعل من ضمن مقررات مؤتمر فرساي أن تتولي الولايات المتحدة، الدولة الوحيدة التي لم تتأثر بشدة بالحرب حيث أنها دخلتها متأخرة جدا، تتولي توريد المواد الغذائية إلي بلجيكا لكي لا يهلك شعبها. وقد كان رئيس ادارة الإغاثة الأمريكية American Relief Administration هو مهندس مناجم نجح في عمله الهندسي في خارج وداخل الولايات المتحدة حيث عمل في الصين وأستراليا وهو هربرت هوفر. وقد تبغ في التخطيط اللوجستس وإدارة المشاؤيع حتي أنه تقلد ذلك المنصب وأصبح بطلا قوميا داخل الولايات المتحدة ورمزا للكفاءة والقدرة المتميزة في العالم الخارجي. وكان يستقبل بحفاوة أينما حل وفي كل البلاد.

والآن نحن في يوليو 1921 وقد توجه الكاتب الروسي مكسيم جوركي بنداء عبر صحف العالم قال فيه أن بلد ديستويفسكي وتولستوي ومندلييف مقبل علي ايام حالكة وأننا نحتاج إلي مساعدة فورا قبل أن يحل الشتاء ونهلك جميعا.

من يتذكر منكم فيلم دكتور جيفاجو يعرف هذه اللقطة التي تظهر أحذية الجنود مثقوبة وبالية والراوية يقول أن الجنود الذين دخلوا الجيش كانوا سعداء لحصولهم علي أحذية جديدة مجانية، ولكن الأحذية لا تدوم طويلا ولا تتحمل فصلي شتاء متتاليين. لقد باتت الثورة وشيكة خصوصا وأن الهزائم الروسية علي يد الجيش الألماني ثقيلة.

كانت الثورة الروسية من تدبير المخابرات الألمانية عن طريق مد لينين بالمال اللازم ونقله في قطار مغلق من سويسرا إلي روسيا عن طريق السويد. وقد نتج عن تلك الهزائم المتوالية أن أجبر القيصر نيكولا علي التخلي عن العرش وقامت في البلاد حكومة ليبرالية فتحت الباب للحريات وللصحف لأول مرة في التاريخ الروسي الممتد وهي حكومة كيرينسكي التي لم تكن تحظي بإعجاب الشيوعيين مما أدخل البلاد في حرب أهلية بين البلشفيك (الحمر) والمانشفيك (البيض) الذين كانوا معسكرا سائبا لا يربطه رابط سوي الرغبة في محاربة الشيوعية بينما كان المعسكر الشيوعي أفضل تنظيما وأسرع حركة إذ أن ليون تروتسكي أنشأ الجيش الأحمر لكي يواجه به الجيش الأبيض. وهكذا أصبح الحسم بالقوة هو لغة التخاطب بين الطرفين. وقد إستمرت هذه الحرب طويلا بعد نهاية الحرب وحتي عام 1922 بأن حسمها الجيش الأحمر لصالحه.

وقد صاحب هذا التردي في الأوضاع شتاء قارس ومحصول شبه منعدم في ذلك العام 1921. ولذلك أرسل الكاتب مكسيم جوركي نداءه المذكور إلي العالم. كان السيد هوفر بحكم خبرته في بلجيكا قد أصبح من المهتمين بالشئون الدولية وقد قرأ هذا الإعلان في إحدي الصحف وقرر التصرف..

لم يكن هربرت هوفر يميل بأي حال إلي الشيوعية بل أنه كان جمهوريا يري أن السوق المفتوح وحرية التجارة هي من الأمور الهامة التي تميز الدول المتقدمة الناجحة. ولكنه في نفس الوقت كان يري أن إظهار الكفاءة الأمريكية في إدارة المواقف الصعبة وإظهار الرخاء الإقتصادي الذي تتمتع به بلاده هي كلها عوامل يمكنها أن تساعد في تهيئة الظروف لمعسكر لا يؤمن بالشيوعية في روسيا وخصوصا وأن الموقف كان قد بدأ يميل إلي صالح الشيوعيين عندما أعلن جوركي بيانه الشهير دون أن يسأل لينين إذنا أو دون أن يشير إليه وإلي حكومته من قريب أو من بعيد.

والواقع أن أمريكا لم تكن في ذلك الوقت بعيدة عن الصراع الفكري حيث أننا جميعا نتذكر قضية ساكو وفانزيتي التي كانت في أساسها مختلقة لكي تضع مثالا رادعا لكل من يتداول الفكر النقابي أو الإشتراكي. كما أتتا عرفنا عن الإضراب العام في سياتل في ولاية واشنطن أقصي شمال غرب الولايات المتحدة والذي كان يمثل شبحا يتهدد رجال الأعمال. فقد كان الخطر الشيوعي ماثلا علي الأقل في أفكار ومخيلة الطبقة الصناعية المالية الأمريكية. وقد لاقي هربرت هوفر مصاعب في تمرير مشروعه من الكونجرس حيث أنه كان لابد له أن يحصل علي تصريح من الكونجرس لمساعدة المهددين بالموت جوعا في روسيا، معقل الشيوعية وأول بلد في التاريخ تأخذ بهذا النظام السياسي الإقتصادي الإجتماعي الفكري. فماذا فعل لكي يتغلب علي هذه العقبة؟

كان الرئيس الأمريكي وارن هاردنج الجمهوري المنتخب حديثا والذي دخل البيت الأبيض عقب إنتخابات 1920. وقد نجح هوفر في إقناعه بأن مصلحة الولايات المتحدة تكمن في إظهار وجهها الإنساني أمام شعب روسيا الذي يخوض الآن غمار حرب أهلية بين الشيوعيين وخصومهم. كذلك فإن تدخل الولايات المتحدة ذات النظام الراسمالي هو رفع من قدر هذا النظام أمام ناظري الشعب الروسي كما أن الخلاف بين الولايات المتحدة والنظرية الماركسية لا يصح له أن يمتد ليشمل المعونات الإنسانية وقد كان نظر الرئيس الأمريكي موافقا لهذا الرأي. ولكن بقي علي هوفر أن يقنع الكونجرس.

كانت الأحوال الإقتصادية عقب عودة 2 مليون من جنود الجيش الأمريكي إلي الولايات المتحدة عقب نهاية الحرب العالمية الأولي ليست علي ما يرام. وقد كانت هناك بطالة في البلاد كما أن الثورات العمالية المتتالية كانت من عوامل القلق الكبيرة. وبالتالي كان الكونجرس غير محبذ لاعتماد أي مبالغ مالية للخارج في ظل هذه الظروف وبالذات لتقديمها إلي بلد يتهدده النظام الشيوعي تهديدا جديا.

لكن الوجه السياسي الآخر للأمور لم يكن سيئا حيث أن فائضا ضخما من محصول القمح والذرة كان متواجدا في السوق الأمريكي مما يهدد بخفض الأسعار وخسارة الفلاحين، ولذلك فقد نجح هوفر في الحصول علي موافقة الكونجرس بفضل مساندة لوبي المزارعين داخل الكونجرس. وهكذا إعتمد الكونجرس المبلغ اللازم لتنفيذ مشروع هوفر بقدر 20 مليون دولار وهو ما يعادل 600 مليون دولار بأسعار زماننا هذا. كان طريق الشحنات طويلا حيث يبدأ في نيويورك عبورا للأطلنطي ثم مرورا بمضيق جبل طارق فالبحر المتوسط بأكمله مرورا إلي البحر الاسود عبر البوسفور ومن هناك يتم توزيعه علي المناطق التي أضيرت بشدة من الجوع ومعظمها يقع في الجزء الآسيوي من روسيا، أي علي بعد أكثر من 1000 كم. وهو ما يعني الإحتياج إلي شبكة من المواصلات تنهض بهذا العبء الهائل.

كما أن العمل علي أرض روسيا كان يلزمه أفراد كثيرين لكي يقوموا بالتوزيع حيث أن الخطة كانت إنشاء عدد كبير من المراكز التي يتم فيها طهو الطعام ثم توزيعه علي المحتاجين. وقد بلغ عدد هذه المطابخ 19000 مطبخ علي إمتداد القطر كله، وعمل بالمشروع بأسره 120 ألف روسي !! وهؤلاء العاملون لم يكن الحصول عليهم سهلا بالمرة حيث كان الأمريكيون يبحثون عمن يستطيع الحديث بالإنجليزية أو بأي لغة أوروبية معروفة لهم ولكن ذلك كان نادر الوجود بسبب الجهل الهائل المستشري في روسيا.

وإضافة إلي كل هذه العوامل المحبطة كان هناك عامل الوقت حيث أن 25 الف شخص كانوا يموتون كل أسبوع لو لم تصل إليهم إمدادات الطعام. ثم كان هناك تشكك الحكومة الشيوعية المهووسة بالأمن من تهريب الاسلحة وتدريب المخربين ضد الثورة لكي يجهضوا الثورة الوليدة !! وهكذا وجد هوفر وفريقه العامل في روسيا أمام كم كبير وجبل هائل من التحديات، فماذا فعلوا إزاءها؟

أولا لابد من معرفة الأحوال التي كانت سائدة في شرق البلاد حين وصل الأمريكيون إليها لكي يشرفوا علي المشروع الكبير. كانت الغالبية من المتضررين من الجوع هي من الأطفال، إذ أن كثيرا من الآباء والأمهات إما قضوا جوعا وإما هجروا أطفالهم ونزحوا من قراهم. كما أن من بقي في تلك القري لم يكن قادرا علي الحركة من شدة الجوع. وقد لجأ كثيرون إلي أكل القش الذي يستخدم في تغطية البيوت البسيطة في تلك القري. بل أن المقابر قد فتحت وأخرجت أجساد المتوفين حديثا لكي تؤكل من جانب الجائعين. وتمت المتاجرة بالفعل في اللحم البشري للإستخدام كطعام ويذكر الأمريكي ويل شافروت أحد الأعضاء المهمين في تلك المهمة أن الحكومة بعد فترة أمرت بإغلاق 10 محلات جزارة تبيع لحوم الآدميين. هذا طبعا ناهيك عن أكل لحم القطط والكلاب والخيول والحمير. وكان أكل القش يتسبب في إنتفاخ يعطي الإنطباع أن الشخص سمين وصحيح ولكن بعد فترة تظهر عليه أعراض المرض الذي ينتهي بالموت. وقد تسبب كل ذلك فى إنتشار القمل بسبب عدم النظافة وعدم القدرة علي الحركة وهذا القمل كان ناقل لمرض التيفوس وهو مرض قاتل إن لم يعالج مبكرا. القمل في كل مكان، وهو ناقل لمرض التيفوس، لهذا سوف نغطي أنفسنا جيدا بالاغطية الثقيلة ونقضي ليالي سيبيريا الشتوية القارسة في العراء، لأن القمل لا يتحمل البرودة وبالتالي لا تنتقل إلينا العدوي عن طريق القمل.

كان هذا هو وصف ظروف العمل التي يعايشها الأمريكيون أثناء قيامهم بالعمل في هذا المشروع الضخم ولكم جميعا تصور معني المبيت في العراء في شتاء سيبيريا، مهما بلغت كفاءة الأغطية المستعملة.

كان عدد ضحايا الجوع قد وصل تقريبا إلي 5 مليون قبل أن يبدأ مشروع هوفر في الحركة. وكانت بعض الأمهات تعمد إلي قتل ابنائها الأكبر وأكل لحمهم حتي تستطيع إرضاع الأطفال الاصغر!! كانت المأساة رهيبة وإتساعها لا سابق له. وكان موقف الحكومة الروسية متخاذلا لا يهتم إلا بالأولويات التي وضعها الشيوعيون وهي أولا وقبل كل شىء تثبيت قوتهم لكي يتمكنوا من حكم البلاد كاملة. وهذا الموقف بالذات جعل هوفر يحتقر الفكر الشيوعي ويزدريه بشدة مما زاده إصرارا علي إظهار الطبيعة الإنسانية للمشروع الضخم.

كان المديرون المحليون في روسيا للمشروع الأمريكي من ضباط الجيش الأمريكي المتقاعدين وذلك لضمان إحكام الربط والإلتزام. وكانت أول عقبة تواجه إنقاذ الأرواح هي التخلف الشديد الذي كانت تعاني منه شبكة السكك الحديدية التي يقع عليها العبء الأعظم في النقل. ووقع أول خلاف بينهم وبين مدير السكك الحديدية الذي كان يعمل بالطريقة الروتينية البطيئة ولا يراع ظروف المشروع الطارئة حيث أن كل اسبوع يكلف كما عرفنا حياة 25 الف شخص. وقد كان مدير السكك الحديدية يأمر بتحويل الشحنات أولا إلي العاملين في مرفق السكك الحديدية ليستهلكوها بمعرفتهم أو لكي يبيعونها لصالحهم. وكانت أسباب تلك اللامبالاة تقع في طبيعة الفساد المنتشر في ذلك الوقت في المجتمع الروسي وإلي التثاقل في العمل الذي يتسم به كثير من الروس بالإضافة إلي كون معظم ضحايا الجوع من الشعوب الشرقية الغير روسية مثل البشكير والتتار. أما الروس الذين كانوا يعيشون في هذه المناطق فقد كان كثيرون منهم يرون أن ما يحدث هو إستحقاق رباني لعقاب الروس المسيحيين علي ما وقع في البلاد من ثورة علي القيصر يقودها كفرة شيوعيون دخلوا إلي الكنائس وقاموا بقتل القساوسة ورجال الدين المسيحي ولهذا فعقاب المجتمع هو عقاب عادل!

ولهذا لجا المدير الأمريكي المقيم إلي الإجراء الوحيد الذي يمكنه القيام به في مثل تلك الظروف وهو التهديد بوقف المشروع. ولكن كيف فعل ذلك وكيف كان الاثر منه؟

كانت الشكوي الرئيسية من مرفق السكك الحديدية بسبب فساد رجاله وإهماله وعدم صلاحية عرباته أي خرابه شبه الكامل. ولكن لم يكن هناك من وسيلة للوصل إلي هذه المسافات البعيدة بالسرعة المطلوبة إلا عن طريق السكك الحديدية. لهذا كتب الضابط الأمريكي المسئول برقية مفتوحة بدون شفرة إلي رئيسه هربرت هوفر يطلب منه إيقاف شحن أي كميات من الحبوب من نيويورك حيث أن المشروع لا يتحرك فعليا علي الارض لأن السكك الحديدية غير متعاونة. وبالطبع كان ذلك مقصودا حتي يقرأه المسئولون الروس ويخضعوا للتهديد عن طريق معرفة نوايا اصحاب المشروع الأمريكيين.

وعند هذه النقطة خشي الروس ان ينقطع المشروع بالفعل وأن تقوم في البلاد ثورة الجياع التي قد تضعف مركزهم أو تنهيه بالكامل فاقالوا مدير السكك الحديدية ووضعوا مكانه رئيس جهاز أمن الثورة الذي إشتهر عنه عدم التردد في قتل من يري فيه خطرا علي الثورة. وبذلك فهم كل عامل في السكة الحديد أنه إما أن يعمل علي قدر طاقته أو سوف يتلقي رصاصة تخترق راسه!! هكذا كان أثر البرقية.

والسبب الاساسي الذي جعل الضابط الأمريكي يتصرف بهذه الطريقة هو أن موعد غرس بذور المحصول الجديد من الذرة والقمح هو ربيع عام 1922 وذلك إن كان يرجي جني أي محصول في خريف ذلك العام لكي يقي البلاد شر مجاعة جديدة العام القادم. ولما كان الموعد يقترب والبذور لم يتم توصيلها بعد فقد رأي ذلك الضابط أن الخطر سوف يتكرر إن هو لم يقم بعمل حاسم. وكان من ضمن شروط عقد المشروع التي وقع عليها ممثلو الحكومة الروسية أن يشتروا بذور الغلال من الولايات المتحدة ويقومون بغرسها في الوقت المناسب حتي يكون هناك محصول جديد. وقد رأي كل من الضابط هيسكل ورئيسه هوفر في عدم غرس بذور الغلال حتي هذا الموعد المتأخر خرقا لبنود العقد المبرم. وبالفعل تحرك مرفق السكة الحديد بطريقة أفضل تحت تهديد قطع المشروع وتحت سمعة رئيس الجهاز الأمني وبدأ تدفق الغلال يتحسن خلال ربيع وصيف 1922.

ومن ألطف الاشياء التي يمكن للمرء أن يقرأها هو وصف الأمريكيين لطريقة عمل الروس وأسلوب حياتهم. فقد كان من نتائج هذا المشروع أن تلاقت الثقافتان بطريقة مباشرة وظهرت الفوارق. فالأمريكيون يتوقعون من الروس أن يبدأوا العمل في تمام الثامنة صباحا ولكن العاملين الروس لم يكنوا يظهرون في أماكن العمل قبل العاشرة أو التاسعة والنصف وكانت حججهم دائما من نفس نوع حجج المصريين التي نعرفها، أمي مريضة، إبني سخن، كنت أبيع خروفا في السوق لأنه سوف يغلق عند الظهر إلخ... وعلي الجانب الآخر فإن الأمريكيين لم يكنوا مستعدين علي الإطلاق للتعامل مع حضارات وأعراق مختلفة تعيش جنبا إلي جنب. فالبشكير المسلمون لا يحبون الكازاخ المسلمين أيضا وكلاهما يكره الروس. وهكذا وجد المسئولون عن المشروع أنفسهم داخلين في موازنات سياسية وعرقية ليس لهم بها أي معرفة ولا إتصال.

وفي خريف عام 1922 بدأت بوادر المحصول الجديد في الظهور وبذلك نجحت مهمة هوفر في روسيا ولكن المشروع بقي يعمل بطريقة مخفضة حتي خريف العام التالي 1923 حين خرج آخر أمريكي من روسيا. ومما هو جدير بالذكر أن تلك الفترة في بداية عام 1922 هي نفسها التي شهدت توقيع إتفاقية راباللو بين الإتحاد السوفيتي وألمانيا حول التعاون في عديد من المجالات وهو ما سوف يسفر عنه بعد ذلك تقوية الطرفين كل في مجاله تمهيدا للحرب القادمة.

وهربرت هوفر المهندس الكفء قال بعد ذلك بحوالي 10 سنوات أنه كان يظن أن مشروعه لإنقاذ الجائعين الروس سوف يساهم في إضعاف الفكرة الشيوعية بإظهار تهافتها وبيان عجزها إلا أن أمله قد خاب ووجد نفسه في النهاية وقد ساهم في نجاح سيطرتها علي روسيا.

وهو علي كل حال قد تعرض لمحنة أشد كثيرا من مجرد إدارة مشروع عاجل، وهي محنة الكساد الأمريكي الداخلي والذي إمتد ليشمل العالم كله فلم يستطع بقدراته الهندسية أن يجد لها أي حل بل وجد الحل فيما بعد تشريعيا علي يد رئيس آخر ديموقراطي هو رجل القانون فرانكلين روزفلت الذي إنتقد هوفر علنا في وجهه أثناء إلقاء كلمة حفل تنصيبه خلفا لهوفر في يناير 1932.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاتجاه للسياسة الداخلية

وإبان الحرب العالمية الأولى استيقظ جانب الكويكر في هوفر، فتعب من جمع المال، و تفرغ للأعمال الإنسانية، فأحرز قبولاً واسعاً، وحصل على نفوذ كبير، ثم اختار الإشتغال بالسياسة، فأصبح وزير التجارة في عهد هاردنگ ودعم حملة كوليدج، ثم ترشح هو نفسه للإنتخابات الرئاسية الأمريكية.

الادارة والوزارة

| المنصب | الاسم | الفترة | ||||

| الرئيس | هربرت هوڤر | 1929-1933 | ||||

| نائب الرئيس | تشارلز كرتس | 1929-1933 | ||||

| وزير الخارجية | هنري ستمسون | 1929-1933 | ||||

| وزير الخزانة | أندرو ملون | 1929-1932 | ||||

| اوگدن ميلز | 1932-1933 | |||||

| وزير الحربية | جيمس و. گود | 1929 | ||||

| پاتريك هرلي | 1929-1933 | |||||

| المدعي العام | وليام د. متشل | 1929-1933 | ||||

| Postmaster General | Walter F. Brown | 1929-1933 | ||||

| وزير البحرية | تشارلز ف. أدمز | 1929-1933 | ||||

| Secretary of the Interior | Ray L. Wilbur | 1929-1933 | ||||

| وزير الزراعة | آرثر م. هايد | 1929-1933 | ||||

| وزير التجارة | روبرت پ. لامونت | 1929-1932 | ||||

| روي چاپن | 1932-1933 | |||||

| وزير العمل | جيمس ديڤس | 1929-1930 | ||||

| وليام دواك | 1930-1933 | |||||

بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية

رئاسته 1929-1933

Hoover saw the presidency as a vehicle for improving the conditions of all Americans by encouraging public-private cooperation—what he termed "volunteerism". He tended to oppose governmental coercion or intervention, as he thought they infringed on American ideals of individualism and self-reliance.[4] The first major bill that he signed, the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929, established the Federal Farm Board in order to stabilize farm prices.[5] Hoover made extensive use of commissions to study issues and propose solutions, and many of those commissions were sponsored by private donors rather than by the government. One of the commissions started by Hoover, the Research Committee on Social Trends, was tasked with surveying the entirety of American society.[6] He appointed a Cabinet consisting largely of wealthy, business-oriented conservatives,[7] including Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon.[8] Lou Henry Hoover was an activist First Lady. She typified the new woman of the post–World War I era: intelligent, robust, and aware of multiple female possibilities.[9]

الكساد الكبير

لوقت كبير كان هوڤر من دعاة التعاون بين القطاعين العام والخاص كوسيلة لتحقيق النمو على المدى الطويل.[10] خشي هوڤر من أن المزيد من التدخل الحكومي من شأنه أن يقوض الفردية والاعتماد على الذات على المدى الطويل، والتي اعتبرها ضرورية لمستقبل الأمة. كانت مثله والاقتصاد على المحك عند بداية الكساد الكبير.[11]

بالرغم من أن الكثير من الأشخاص في ذلك الوقت ولعقود تالية استنكروا على هوڤر تبنيه سياسة عدم التدخل في الكساد،[12] وركز بعض المؤرخين على الكيفية التعامل الحقيقي لهوڤر مع الكساد الكبير قال هوڤر أنه رفض منهج "دعه وشأنه" الذي اقترحه وزير الخزانة أندرو ملون،[13] ودعا الكثير من قادة الأعمال إلى واشنطن لحثهم على عدم تسريح العمال أو تخفيض أجورهم.[14]

يزعم الاقتصادي الليبرالي مري روثبارد أن هوڤر كان في الواقع أول من بادر فيما يعرف بالصفقة الجديدة. شارك هوڤور في العديد من برامج الأشغال العامة الغير مسبوقة، وتشمل زيادة في برنامج المباني الفدرالية بأكثر من 400 مليون دولار وتأسيس ادارة الانشاءات العامة لتحفيز تخطيط الأشغال العامة. منح هوڤر نفسه المزيد من الدعم لانشاءات الشحن عن طريق مجلس الشحن الفدرالي وطالب باعتمدات إضافية قيمتها 175 مليون دولار من أجل الأشغال العامة؛ تلا هذا في يوليو 1930 بإنفاق 915 مليون دولار على برنامج الأشغال العامة، والتي شملت سد هوڤر على نهر كلورادو.[15][16] في ربيع 1930، حصل هوڤر على 100 مليون دولار إضافية من أجل سياسات الإقراض والشراء في مجلس المزارع الفدرالية. عند نهاية 1929، أسس مجلس المزارع الفدرالية تعاونية الصوف الوطنية-مؤسسة تسويق الصوف الوطنية (NWMC) والتي ضمت أكثر من 30 اتحاد ولائي. أسس المجلس أيضاً مؤسسة إقراض الصوف الوطنية المتضامنة من أجل المعاملات المالية. قدم مجلس المزارع الفدرالية قروض وصلت قيمتها الإجمالية إلى 31.5 مليون دولار، منها 12.5 مليون دولار فقدت permanently ؛ كانت هذه الإعانات الزراعية الضخمة سابقة لقانون التعديل الزراعي اللاحق.[17][18] كذلك، دافع هوڤر بقوة عن قانون تنظيم العمل، والذي يشمل تشريع قانون بيكون-ديڤيز، ويتطلق يوم عمل ثمان ساعات بحد أقصى لإنشاء المباني العامة ودفع "الأجور السائدة" محلياً، بالإضافة إلى قانون نوريس-لاگوارديا عام 1932. في قطاع الصرافة، مرر هوڤر قانون بنك القروض الفدرالية في يوليو 1932، لتأسيس 12 بنك district تحت إدارة مجلس القروض الفدرالية على غرار نظام الاحتياط الفدرالي. 125 مليون دولار كانت قيمة رأس المال المكتبب من قبل الخزانة والذي تم تحويله لاحقاً إلى مجلس القروض الفدرالية. لعب هوڤر دوراً رئيسياً في تمرير قانون گلاس-ستيگال لعام 1932، الذي يسمح بإعادة الخصم (التخفيض) تحت سعر الفائدة الفضلى في الاحتياط الفدرالي، ويسمح بالمزيد من الضخم في القروض واحتياطيات البنوك.[19]

ليو اوهانيان، من جامعة كاليفورنيا، لوس أنجلس، يزعم أن هوڤر قد تبنى سياسات داعمة للعمل بعد انهيار سوق البورصة عام 1929 والذي "مثل ما يقارب من ثلاثي الانخفاض في الناتج المحلي الإجمالي على مدار العامين التاليين، مما تسبب فيما هو أسوأ من الكساد السيء بالإنزلاق في الكساد الكبير".[20] هذا الدفع يتعارض مع وجهة النظر الأكتر كينزية لأسباب الكساد، وقد اتُهِم بأنه يعيد كتابة التاريخ من قِبل ج. برادفورد ديلونگ من جامعة كاليفورنيا بركلي.[21]

تزايد الدعوات لمساعدة حكومية أكبر مع استمرار تراجع الاقتصاد الأمريكي. كان أيضاً يؤمن بشدة بالميزانيات المتوازنة (كما هو الحال لدى معظم الديمقراطيين)، ولم يكن يرغب في استخدام عجز الميزانية في برامج صندوق الرفاه.[22] ومع ذلك، لم يتبنى هوڤر الكثير من السياسات لإخراج البلاد من الكساد. عام 1929 صاغ برنامج إعادة التوطين المكسيكي لمساعدة المواطنين المكسيكيين العاطلين على العودة لوطنهم. كان هذا البرنامج عبارة عن هجرة قسرية واسعة النطاق لما يقارب 500.000 شخص إلى المكسيك، واستمر حتى عام 1937. في يونيو 1930، بناءاً على اعتراض الكثير من الاقتصاديين، صدق الكونگرس ووقع هوڤر على مضض، قانون تعريفة سموت-هاولي. فرض التشريع الرسوم الجمركية على آلاف السلع المستوردة. كان هذا القانون يهدف إلى تشجيع شراء المنتجات الأمريكية بزيادة تكلفة السلع المستوردة، مما يزيد من عائدات الحكومة الفدرالية ويحمي المزارعين. ومع ذلك، فقد انتشر الكساد الاقتصادي عالمياً، وردت كندا، فرنسا ودول أخرى برفع الرسوم الجمركية على السلع الأمريكية. أثر هذا على نشاط التجارة الدولية، وتفاقم الكساد.[23]

عام 1931، أصدر هوڤر وقف هوڤر، منادياً بوقف لمدة سنة لدفعات التعويضات التي تدفعها ألمانيا لفرنسا وفي تسديد الحلفاء للديون الحرب للولايات المتحدة. لاقت الخطة معارضة كبيرة، خاصة من فرنسا، التي ألحقت بها ألمانيا خسائر فادحة أثناء الحرب. لم يفعل الوقف الكثير لتخفيف التراجع الاقتصادي. بعد أن أوشك الوقف على الانتهاء في العام التالي، كانت هناك محاولة للوصول إلى حل دائم في مؤتمر لوزان 1932. ولم يتم التوصل إلى تسوية فعالة، ومع بدأ الحرب العالمية الثانية، توقف سداد التعويضات تماماً.[24][25] عام 1931 دعا هوڤر البنوك الكبرى في البلاد لتشكيل كونسورتيوم يعرف بالمؤسسة الوطنية للائتمان (NCC).[26]

في الولايات المتحدة، بحلول عام 1932 وصلت البطالة إلى 24.9%،[27] وعجزت الأعمال عن سداد أعداد قياسية من الديون، وخسر أكثر من 5.000 بنك.[28] وجد مئات الآلاف من الأمريكان أنفسهم بلا مأوى وبدأ التجمع في أعداد من الهوڤرڤيلات (مدن الصفيح) التي ظهرت في المدن الكبرى.

الكونگرس، في محاولة يائسة لزيادة العوائد الفدرالية، أصدر قانون العوائد 1932، والذي كان يعتبر أكبر زيادة للضرائب في وقت السلم في التاريخ.[29] زاد القانون الضرائب في جميع المجالات، لذا كانت الضرائب تفرض على كبار الملاك على 63% من دخلهم الصافي. كذلك رفع قانون 1932 الضرائب على الدخل الصافي للشركات من 12% إلى 13.75%.

تمت المحاولة الأخيرة لادارة هوڤور لإنقاذ الاقتصاد عام 1932 بتمرير قانون إغاثة وإنشاءات الطوارئ، والذي يكلف الصناديق ببرامج الأشغال العامة وإنشاء مؤسسة تمويل الانشاءات. كان الهدف المبدئ لهذه المؤسسة هو توفير قروض بضمان حكومي للمؤسسات المالية، السكك الحديدية والمزارعين. كان لهذه المؤسسة أثر ضئيل في ذلك الوقت، لكن تم تبنيها من قبل الرئيس فرانكلين د. روزڤلت وتوسيعها بشكل كبير لتصبح جزءاً من النيو ديل.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاقتصاد

من أجل تمويل هذا وتمويل البرامج الحكومية الأخرى، وافق هوڤر على واحدة من أكبر الزيادات في الضرائب في التاريخ الأمريكي. قانون العوائد 1932 والذي رفع ضريبة الدخل على الدخول العليا من 25% إلى 63%. تم مضاعفة ضريبة العقارات وزادت ضريبة الشركات بنسبة 15%. أيضاً، "ضريبة الشيكات" والتي تضمنت إضافة ضريبة قيمتها 2 سنت (أكثر من 30 سنت مقارنة بسعر الدولار الآن) على جميع الشيكات البنكية. الاقتصادي وليام د. لاستراپس وجورج سلگين،[30] توصلا إلى أن ضريب الشيكات كانت "عامل مساهم هام في تحقيق الانكماش النقدي في تلك الفترة". كذلك شجع هوڤر الكونگرس على استوجاب بورصة نيويورك، وتجلى هذا الضغط في الاصلاحات المختلفة.

لهذا السبب، زعم الليبرتاريون في السنوات اللاحقة أن اقتصاد هوڤور كان قائم على سيطرة الدولة. انتقد فرانكلين ف. روزڤلت الحزب الجمهوري الشاغر من أجل الإنفاق وفرض المزيد من الضرائب، زيادة الدين القومي، زيادة الرسوم الجمركية وعرقلة التجارة، وكذلك إنفاق الملايين على الإعانات الحكومية. هاجم روزڤلت هوڤر على الإنفاق "المتهور والمسرف"، التفكير "في أنه يتوجب علينا السيطرة مركزياً على كل شيء في واشنطن بأسرع وقت ممكن"، وقيادة "ادارة أكبر إنفاق في وقت السلم على مدار التاريخ". الشريك الانتخابي لروزڤلت، جون نانس گارنر، اتهم الحزب الجمهوري "بقيادة البلاد نحو الاشتراكية".[31]

تضاءت هذه السياسات جنباً إلى جنب مع الخطوات المأساوية التي أتخذت لاحقاً كجزء من الصفقة الجديدة. معارضو هوڤر اتهموه بأن سياساته كانت ضئيلة للغاية، ومتأخرة أيضاً، وأنه لم يقم بعمله. حتى عندما طلب من الكونگرس إصدار تشريع، كرر رأيته في لا ينبغي أن يعاني الشعب من الجوع والبرد، وأن العناية به يجب أن تكون بصفة رئيسية مسئولية محلية وتطوعية.

ومع ذلك، فمدعم النيو ديل، ركسفورد توگويل[32] أشار لاحقاً إلى أنه بالرغم من أنه لا ينبغي على أحد قول هذا في ذلك الوقت، "خاصة أن النيو ديل بالكامل كانت امتداداً لبرامج التي بدأها هوڤر."

Early policies

Though he attempted to put a positive spin on Black Tuesday, Hoover moved quickly to address the stock market collapse.[33] In the days following Black Tuesday, Hoover gathered business and labor leaders, asking them to avoid wage cuts and work stoppages while the country faced what he believed would be a short recession similar to the Depression of 1920–21.[34] Hoover also convinced railroads and public utilities to increase spending on construction and maintenance, and the Federal Reserve announced that it would cut interest rates.[35] In early 1930, Hoover acquired from Congress an additional $100 million to continue the Federal Farm Board lending and purchasing policies.[36] These actions were collectively designed to prevent a cycle of deflation and provide a fiscal stimulus.[35] At the same time, Hoover opposed congressional proposals to provide federal relief to the unemployed, as he believed that such programs were the responsibility of state and local governments and philanthropic organizations.[37]

Hoover had taken office hoping to raise agricultural tariffs in order to help farmers reeling from the farm crisis of the 1920s, but his attempt to raise agricultural tariffs became connected with a bill that broadly raised tariffs.[38] Hoover refused to become closely involved in the congressional debate over the tariff, and Congress produced a tariff bill that raised rates for many goods.[39] Despite the widespread unpopularity of the bill, Hoover felt that he could not reject the main legislative accomplishment of the Republican-controlled 71st Congress. Over the objection of many economists, Hoover signed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act into law in June 1930.[40] Canada, France, and other nations retaliated by raising tariffs, resulting in a contraction of international trade and a worsening of the economy.[41] Progressive Republicans such as Senator William E. Borah of Idaho were outraged when Hoover signed the tariff act, and Hoover's relations with that wing of the party never recovered.[42]

Later policies

By the end of 1930, the national unemployment rate had reached 11.9 percent, but it was not yet clear to most Americans that the economic downturn would be worse than the Depression of 1920–21.[43] A series of bank failures in late 1930 heralded a larger collapse of the economy in 1931.[44] While other countries left the gold standard, Hoover refused to abandon it;[45] he derided any other monetary system as "collectivism".[46] Hoover viewed the weak European economy as a major cause of economic troubles in the United States.[47] In response to the collapse of the German economy, Hoover marshaled congressional support behind a one-year moratorium on European war debts.[48] The Hoover Moratorium was warmly received in Europe and the United States, but Germany remained on the brink of defaulting on its loans.[49] As the worldwide economy worsened, democratic governments fell; in Germany, Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler assumed power and dismantled the Weimar Republic.[50]

By mid-1931, the unemployment rate had reached 15 percent, giving rise to growing fears that the country was experiencing a depression far worse than recent economic downturns.[51] A reserved man with a fear of public speaking, Hoover allowed his opponents in the Democratic Party to define him as cold, incompetent, reactionary, and out-of-touch.[52] Hoover's opponents developed defamatory epithets to discredit him, such as "Hooverville" (the shanty towns and homeless encampments), "Hoover leather" (cardboard used to cover holes in the soles of shoes), and "Hoover blanket" (old newspaper used to cover oneself from the cold).[53] While Hoover continued to resist direct federal relief efforts, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York launched the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration to provide aid to the unemployed. Democrats positioned the program as a kinder alternative to Hoover's alleged apathy towards the unemployed, despite Hoover's belief that such programs were the responsibility of state and local governments.[54]

The economy continued to worsen, with unemployment rates nearing 23 percent in early 1932,[55] and Hoover finally heeded calls for more direct federal intervention.[56] In January 1932, he convinced Congress to authorize the establishment of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which would provide government-secured loans to financial institutions, railroads, and local governments.[57] The RFC saved numerous businesses from failure, but it failed to stimulate commercial lending as much as Hoover had hoped, partly because it was run by conservative bankers unwilling to make riskier loans.[58] The same month the RFC was established, Hoover signed the Federal Home Loan Bank Act, establishing 12 district banks overseen by a Federal Home Loan Bank Board in a manner similar to the Federal Reserve System.[59] He also helped arrange passage of the Glass–Steagall Act of 1932, emergency banking legislation designed to expand banking credit by expanding the collateral on which Federal Reserve banks were authorized to lend.[60] As these measures failed to stem the economic crisis, Hoover signed the Emergency Relief and Construction Act, a $2 billion public works bill, in July 1932.[55]

Budget policy

After a decade of budget surpluses, the federal government experienced a budget deficit in 1931.[61] Though some economists, like William Trufant Foster, favored deficit spending to address the Great Depression, most politicians and economists believed in the necessity of keeping a balanced budget.[62] In late 1931, Hoover proposed a tax plan to increase tax revenue by 30 percent, resulting in the passage of the Revenue Act of 1932.[63] The act increased taxes across the board, rolling back much of the tax cut reduction program Mellon had presided over during the 1920s. Top earners were taxed at 63 percent on their net income, the highest rate since the early 1920s. The act also doubled the top estate tax rate, cut personal income tax exemptions, eliminated the corporate income tax exemption, and raised corporate tax rates.[64] Despite the passage of the Revenue Act, the federal government continued to run a budget deficit.[65]

Civil rights and Mexican Repatriation

Hoover seldom mentioned civil rights while he was president. He believed that African Americans and other races could improve themselves with education and individual initiative.[66] Hoover appointed more African Americans to federal positions than Harding and Coolidge combined, but many African-American leaders condemned various aspects of the Hoover administration, including Hoover's unwillingness to push for a federal anti-lynching law.[67] Hoover also continued to pursue the lily-white strategy, removing African Americans from positions of leadership in the Republican Party in an attempt to end the Democratic Party's dominance in the South.[68] Though Robert Moton and some other black leaders accepted the lily-white strategy as a temporary measure, most African-American leaders were outraged.[69] Hoover further alienated black leaders by nominating conservative Southern judge John J. Parker to the Supreme Court; Parker's nomination ultimately failed in the Senate due to opposition from the NAACP and organized labor.[70] Many black voters switched to the Democratic Party in the 1932 election, and African Americans would later become an important part of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal coalition.[71]

As part of his efforts to limit unemployment, Hoover sought to cut immigration to the United States, and in 1930 he promulgated an executive order requiring individuals to have employment before migrating to the United States.[72] The Hoover Administration began a campaign to prosecute illegal immigrants in the United States, which most strongly affected Mexicans, especially those living in Southern California.[73][74] During the 1930s, between 355,000 and one million Mexicans and Mexican Americans were repatriated or deported to Mexico; an estimated forty to sixty percent of whom were birthright citizens - overwhelmingly children.[75][76] Some scholars contend that the unprecedented number of repatriations between 1929 and 1933 were part of an “explicit Hoover administration policy".[75] While supported and encouraged by the federal government, most deportations and repatriations were organized by local and state governments, often with support from local private entities. Voluntary repatriation was far more common than formal deportation, with 34,000 people deported to Mexico by the federal government between 1930 and 1933.[75][77] According to legal professor Kevin R. Johnson, the repatriation campaigns were a form of ethnic cleansing against an ethnic minority.[78]

He reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs to limit exploitation of Native Americans.[79]

Prohibition

On taking office, Hoover urged Americans to obey the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, which had established Prohibition across the United States.[80] To make public policy recommendations regarding Prohibition, he created the Wickersham Commission.[81] Hoover had hoped that the commission's public report would buttress his stance in favor of Prohibition, but the report criticized the enforcement of the Volstead Act and noted the growing public opposition to Prohibition. After the Wickersham Report was published in 1931, Hoover rejected the advice of some of his closest allies and refused to endorse any revision of the Volstead Act or the Eighteenth Amendment, as he feared doing so would undermine his support among Prohibition advocates.[82] As public opinion increasingly turned against Prohibition, more and more people flouted the law, and a grassroots movement began working in earnest for Prohibition's repeal.[83] In January 1933, a constitutional amendment repealing the Eighteenth Amendment was approved by Congress and submitted to the states for ratification. By December 1933, it had been ratified by the requisite number of states to become the Twenty-first Amendment.[84]

Foreign relations

According to Leuchtenburg, Hoover was "the last American president to take office with no conspicuous need to pay attention to the rest of the world". Nevertheless, during Hoover's term, the world order established in the immediate aftermath of World War I began to crumble.[85] As president, Hoover largely made good on his pledge made prior to assuming office not to interfere in Latin America's internal affairs. In 1930, he released the Clark Memorandum, a rejection of the Roosevelt Corollary and a move towards non-interventionism in Latin America. Hoover did not completely refrain from the use of the military in Latin American affairs; he thrice threatened intervention in the Dominican Republic, and he sent warships to El Salvador to support the government against a left-wing revolution.[86] Notwithstanding those actions, he wound down the Banana Wars, ending the occupation of Nicaragua and nearly bringing an end to the occupation of Haiti.[87]

Hoover placed a priority on disarmament, which he hoped would allow the United States to shift money from the military to domestic needs.[88] Hoover and Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson focused on extending the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, which sought to prevent a naval arms race.[89] As a result of Hoover's efforts, the United States and other major naval powers signed the 1930 London Naval Treaty.[90] The treaty represented the first time that the naval powers had agreed to cap their tonnage of auxiliary vessels, as previous agreements had only affected capital ships.[91]

At the 1932 World Disarmament Conference, Hoover urged further cutbacks in armaments and the outlawing of tanks and bombers, but his proposals were not adopted.[91]

In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, defeating the Republic of China's National Revolutionary Army and establishing Manchukuo, a puppet state. The Hoover administration deplored the invasion, but also sought to avoid antagonizing the Japanese, fearing that taking too strong a stand would weaken the moderate forces in the Japanese government and alienate a potential ally against the Soviet Union, which he saw as a much greater threat.[92] In response to the Japanese invasion, Hoover and Secretary of State Stimson outlined the Stimson Doctrine, which held that the United States would not recognize territories gained by force.[93]

Bonus Army

Thousands of World War I veterans and their families demonstrated and camped out in Washington, DC, during June 1932, calling for immediate payment of bonuses that had been promised by the World War Adjusted Compensation Act in 1924; the terms of the act called for payment of the bonuses in 1945. Although offered money by Congress to return home, some members of the "Bonus Army" remained. Washington police attempted to disperse the demonstrators, but they were outnumbered and unsuccessful. Shots were fired by the police in a futile attempt to attain order, and two protesters were killed while many officers were injured. Hoover sent U.S. Army forces led by General Douglas MacArthur to the protests. MacArthur, believing he was fighting a Communist revolution, chose to clear out the camp with military force. Though Hoover had not ordered MacArthur's clearing out of the protesters, he endorsed it after the fact.[94] The incident proved embarrassing for the Hoover administration and hurt his bid for re-election.[95]

حملة إعادة الانتخاب 1932

By mid-1931 few observers thought that Hoover had much hope of winning a second term in the midst of the ongoing economic crisis.[96] The Republican expectations were so bleak that Hoover faced no serious opposition for re-nomination at the 1932 Republican National Convention. Coolidge and other prominent Republicans all passed on the opportunity to challenge Hoover.[97] Franklin D. Roosevelt won the presidential nomination on the fourth ballot of the 1932 Democratic National Convention, defeating the 1928 Democratic nominee, Al Smith. The Democrats attacked Hoover as the cause of the Great Depression, and for being indifferent to the suffering of millions.[98] As Governor of New York, Roosevelt had called on the New York legislature to provide aid for the needy, establishing Roosevelt's reputation for being more favorable toward government interventionism during the economic crisis.[99] The Democratic Party, including Al Smith and other national leaders, coalesced behind Roosevelt, while progressive Republicans like George Norris and Robert La Follette Jr. deserted Hoover.[100] Prohibition was increasingly unpopular and wets offered the argument that states and localities needed the tax money. Hoover proposed a new constitutional amendment that was vague on particulars. Roosevelt's platform promised repeal of the 18th Amendment.[101][102]

Hoover originally planned to make only one or two major speeches and to leave the rest of the campaigning to proxies, as sitting presidents had traditionally done. However, encouraged by Republican pleas and outraged by Democratic claims, Hoover entered the public fray. In his nine major radio addresses Hoover primarily defended his administration and his philosophy of government, urging voters to hold to the "foundations of experience" and reject the notion that government interventionism could save the country from the Depression.[103] In his campaign trips around the country, Hoover was faced with perhaps the most hostile crowds ever seen by a sitting president. Besides having his train and motorcades pelted with eggs and rotten fruit, he was often heckled while speaking, and on several occasions, the Secret Service halted attempts to hurt Hoover, including capturing one man nearing Hoover carrying sticks of dynamite, and another already having removed several spikes from the rails in front of the president's train.[104] Hoover's attempts to vindicate his administration fell on deaf ears, as much of the public blamed his administration for the depression.[105] In the electoral vote, Hoover lost 59–472, carrying six states.[106] Hoover won 39.7 percent of the popular vote, a plunge of 26 percentage points from his result in the 1928 election.[107]

العمل الانساني

Post-presidency (1933–1964)

Roosevelt administration

Opposition to New Deal

Hoover departed from Washington in March 1933, bitter at his election loss and continuing unpopularity.[108] As Coolidge, Harding, Wilson, and Taft had all died during the 1920s or early 1930s and Roosevelt died in office, Hoover was the sole living ex-president from 1933 to 1953. He and his wife lived in Palo Alto until her death in 1944, at which point Hoover began to live permanently at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York City.[109] During the 1930s, Hoover increasingly self-identified as a conservative.[110] He closely followed national events after leaving public office, becoming a constant critic of Franklin Roosevelt. In response to continued attacks on his character and presidency, Hoover wrote more than two dozen books, including The Challenge to Liberty (1934), which harshly criticized Roosevelt's New Deal. Hoover described the New Deal's National Recovery Administration and Agricultural Adjustment Administration as "fascistic", and he called the 1933 Banking Act a "move to gigantic socialism".[111]

Only 58 when he left office, Hoover held out hope for another term as president throughout the 1930s. At the 1936 Republican National Convention, Hoover's speech attacking the New Deal was well received, but the nomination went to Kansas Governor Alf Landon.[112] In the general election, Hoover delivered numerous well-publicized speeches on behalf of Landon, but Landon was defeated by Roosevelt.[113] Though Hoover was eager to oppose Roosevelt at every turn, Senator Arthur Vandenberg and other Republicans urged the still-unpopular Hoover to remain out of the fray during the debate over Roosevelt's proposed Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937. At the 1940 Republican National Convention, he again hoped for the presidential nomination, but it went to the internationalist Wendell Willkie, who lost to Roosevelt in the general election.[114]

World War II

During a 1938 trip to Europe, Hoover met with Adolf Hitler and stayed at Hermann Göring's hunting lodge.[115] He expressed dismay at the persecution of Jews in Germany and believed that Hitler was mad, but did not present a threat to the U.S. Instead, Hoover believed that Roosevelt posed the biggest threat to peace, holding that Roosevelt's policies provoked Japan and discouraged France and the United Kingdom from reaching an "accommodation" with Germany.[116] After the September 1939 invasion of Poland by Germany, Hoover opposed U.S. involvement in World War II, including the Lend-Lease policy.[117] He was active in the isolationist America First Committee.[118] He rejected Roosevelt's offers to help coordinate relief in Europe,[119] but, with the help of old friends from the CRB, helped establish the Commission for Polish Relief.[120] After the beginning of the occupation of Belgium in 1940, Hoover provided aid for Belgian civilians, though this aid was described as unnecessary by German broadcasts.[121][122]

In December 1939, sympathetic Americans led by Hoover formed the Finnish Relief Fund to donate money to aid Finnish civilians and refugees after the Soviet Union had started the Winter War by attacking Finland, which had outraged Americans.[123] By the end of January, it had already sent more than two million dollars to the Finns.[124]

During a radio broadcast on June 29, 1941, one week after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Hoover disparaged any "tacit alliance" between the U.S. and the USSR, stating, "if we join the war and Stalin wins, we have aided him to impose more communism on Europe and the world... War alongside Stalin to impose freedom is more than a travesty. It is a tragedy."[125] Much to his frustration, Hoover was not called upon to serve after the United States entered World War II due to his differences with Roosevelt and his continuing unpopularity.[109] He did not pursue the presidential nomination at the 1944 Republican National Convention, and, at the request of Republican nominee Thomas E. Dewey, refrained from campaigning during the general election.[126] In 1945, Hoover advised President Harry S. Truman to drop the United States' demand for the unconditional surrender of Japan because of the high projected casualties of the planned invasion of Japan, although Hoover was unaware of the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb.[127]

Post–World War II

Following World War II, Hoover befriended President Harry S. Truman despite their ideological differences.[128] Because of Hoover's experience with Germany at the end of World War I, in 1946 Truman selected the former president to tour Allied-occupied Germany and Rome, Italy to ascertain the food needs of the occupied nations. After touring Germany, Hoover produced a number of reports critical of U.S. occupation policy.[129] He stated in one report that "there is the illusion that the New Germany left after the annexations can be reduced to a 'pastoral state.' It cannot be done unless we exterminate or move 25,000,000 people out of it."[130] On Hoover's initiative, a school meals program in the American and British occupation zones of Germany was begun on April 14, 1947; the program served 3,500,000 children.[131]

Even more important, in 1947 Truman appointed Hoover to lead the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government a new high level study. Truman accepted some of the recommendations of the "Hoover Commission" for eliminating waste, fraud, and inefficiency, consolidating agencies, and strengthening White House control of policy.[133][134] Though Hoover had opposed Roosevelt's concentration of power in the 1930s, he believed that a stronger presidency was required with the advent of the Atomic Age.[135] During the 1948 presidential election, Hoover supported Republican nominee Thomas Dewey's unsuccessful campaign against Truman, but he remained on good terms with Truman.[136] Hoover favored the United Nations in principle, but he opposed granting membership to the Soviet Union and other Communist states. He viewed the Soviet Union to be as morally repugnant as Nazi Germany and supported the efforts of Richard Nixon and others to expose Communists in the United States.[137]

In 1949, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey offered Hoover the Senate seat vacated by Robert F. Wagner. It was a matter of being senator for only two months and he declined.[138]

Hoover backed conservative leader Robert A. Taft at the 1952 Republican National Convention, but the party's presidential nomination instead went to Dwight D. Eisenhower, who went on to win the 1952 election.[139] Though Eisenhower appointed Hoover to another presidential commission, Hoover disliked Eisenhower, faulting the latter's failure to roll back the New Deal.[135] Hoover's public work helped to rehabilitate his reputation, as did his use of self-deprecating humor; he occasionally remarked that "I am the only person of distinction who's ever had a depression named after him."[140] In 1958, Congress passed the Former Presidents Act, offering a $25,000 yearly pension (equivalent to $201٬384 in 2022) to each former president.[141] Hoover took the pension even though he did not need the money, possibly to avoid embarrassing Truman, whose precarious financial status played a role in the law's enactment.[142] In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy offered Hoover various positions; Hoover declined the offers but defended Kennedy after the Bay of Pigs invasion and was personally distraught by Kennedy's assassination in 1963.[143]

Hoover wrote several books during his retirement, including The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson, in which he strongly defended Wilson's actions at the Paris Peace Conference.[144] In 1944, he began working on Freedom Betrayed, which he often referred to as his "magnum opus". In Freedom Betrayed, Hoover strongly critiques Roosevelt's foreign policy, especially Roosevelt's decision to recognize the Soviet Union in order to provide aid to that country during World War II.[145] The book was published in 2012 after being edited by historian George H. Nash.[146]

Death

Hoover faced three major illnesses during the last two years of his life, including an August 1962 operation in which a growth on his large intestine was removed.[147][148] He died on October 20, 1964, in New York City following massive internal bleeding.[149] Though Hoover's last spoken words are unknown, his last known written words were a get well message to his friend Harry Truman, six days before his death, after he heard that Truman had sustained injuries from slipping in a bathroom: "Bathtubs are a menace to ex-presidents for as you may recall a bathtub rose up and fractured my vertebrae when I was in Venezuela on your world famine mission in 1946. My warmest sympathy and best wishes for your recovery."[150] Two months earlier, on August 10, Hoover reached the age of 90, only the second U.S. president (after John Adams) to do so. When asked how he felt on reaching the milestone, Hoover replied, "Too old."[148] At the time of his death, Hoover had been out of office for over 31 years (11553 days all together). This was the longest retirement in presidential history until Jimmy Carter broke that record in September 2012.[151]

Hoover was honored with a state funeral in which he lay in state in the United States Capitol rotunda.[152] President Lyndon Johnson and First Lady Ladybird Johnson attended, along with former presidents Truman and Eisenhower. Then, on October 25, he was buried in West Branch, Iowa, near his presidential library and birthplace on the grounds of the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. Afterwards, Hoover's wife, Lou Henry Hoover, who had been buried in Palo Alto, California, following her death in 1944, was re-interred beside him.[153] Hoover was the last surviving member of the Harding and Coolidge Cabinets. John Nance Garner (he was Speaker of the House during the second half of Hoover's term) was the only person in Hoover's United States presidential line of succession he did not outlive.

Legacy

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| التيار المحافظ في الولايات المتحدة |

|---|

|

|

Historical reputation

Hoover was extremely unpopular when he left office after the 1932 election, and his historical reputation would not begin to recover until the 1970s. According to Professor David E. Hamilton, historians have credited Hoover for his genuine belief in voluntarism and cooperation, as well as the innovation of some of his programs. However, Hamilton also notes that Hoover was politically inept and failed to recognize the severity of the Great Depression.[154] Nicholas Lemann writes that Hoover has been remembered "as the man who was too rigidly conservative to react adeptly to the Depression, as the hapless foil to the great Franklin Roosevelt, and as the politician who managed to turn a Republican country into a Democratic one".[3] Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Hoover in the bottom third of presidents. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association's Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Hoover as the 36th best president.[155] A 2017 C-SPAN poll of historians also ranked Hoover as the 36th best president.[156]

Although Hoover is generally regarded as having had a failed presidency, he has also received praise for his actions as a humanitarian and public official.[3] Biographer Glen Jeansonne writes that Hoover was "one of the most extraordinary Americans of modern times," adding that Hoover "led a life that was a prototypical Horatio Alger story, except that Horatio Alger stories stop at the pinnacle of success".[157] Biographer Kenneth Whyte writes that, "the question of where Hoover belongs in the American political tradition remains a loaded one to this day. While he clearly played important roles in the development of both the progressive and conservative traditions, neither side will embrace him for fear of contamination with the other."[158]

Historian Richard Pipes, on his actions leading the American Relief Administration, said of him "Many statesmen occupy a prominent place in history for having sent millions to their death; Herbert Hoover, maligned for his performance as President, and soon forgotten in Russia, has the rare distinction of having saved millions."[159]

Views of race

Racist remarks and racial humor was common at the time, but Hoover never indulged in them while President and deliberate discrimination was anathema to him; he thought of himself as a friend to blacks and an advocate for their progress.[160] W. E. B. Du Bois described him as an "undemocratic racist who saw blacks as a species of 'sub-men'".[161]

Memorials

The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum is located in West Branch, Iowa next to the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. The library is one of thirteen presidential libraries run by the National Archives and Records Administration. The Hoover–Minthorn House, where Hoover lived from 1885 to 1891, is located in Newberg, Oregon. His Rapidan fishing camp in Virginia, which he donated to the government in 1933, is now a National Historic Landmark within the Shenandoah National Park. The Lou Henry and Herbert Hoover House, built in 1919 in Stanford, California, is now the official residence of the president of Stanford University, and a National Historic Landmark. Also located at Stanford is the Hoover Institution, a think tank and research institution started by Hoover.

Hoover has been memorialized in the names of several things, including the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River and numerous elementary, middle, and high schools across the United States. Two minor planets, 932 Hooveria[162] and 1363 Herberta, are named in his honor.[163] The Polish capital of Warsaw has a square named after Hoover,[164] and the historic townsite of Gwalia, Western Australia contains the Hoover House Bed and Breakfast, where Hoover resided while managing and visiting the mine during the first decade of the twentieth century.[165] A medicine ball game known as Hooverball is named for Hoover; it was invented by White House physician Admiral Joel T. Boone to help Hoover keep fit while serving as president.[166]

A plaque in Poznań honoring Hoover

Other honors

Hoover was inducted into the National Mining Hall of Fame in 1988 (inaugural class).[167] His wife was inducted into the hall in 1990.[168]

Hoover was inducted into the Australian Prospectors and Miners' Hall of Fame in the category Directors and Management.[169]

Hoover was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Charles University in Prague and University of Helsinki in March 1938.[170][171][172] The ceremonial sword is today on display in the lobby of the Hoover tower.

المصادر

مصادر أساسية

- Myers, William Starr and Walter H. Newton, eds. The Hoover Administration; a documented narrative. 1936.

- Hawley, Ellis, ed. Herbert Hoover: Containing the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President, 4 vols. (1974-1977)

- Hoover, Herbert Clark and Lou Henry Hoover, trans., De Re Metallica, by Agricola, G., The Mining magazine, London, 1912

- De Re Metallica online version

- Hoover, Herbert C. The Challenge to Liberty, 1934

- Hoover, Herbert C. Addresses Upon The American Road, 1933-1938, 1938

- Hoover, Herbert C. Addresses Upon The American Road, 1940-41, (1941)

- Hoover, Herbert C. The Problems of Lasting Peace, with Hugh Gibson, 1942

- Hoover, Herbert C. Addresses Upon The American Road, 1945-48, (1949)

- Hoover, Herbert C. Memoirs. New York, 1951–52. 3 vol; v. 1. Years of adventure, 1874–1920; v. 2. The Cabinet and the Presidency, 1920–1933; v. 3. The Great Depression, 1929–1941.

- Dwight M. Miller and Timothy Walch, eds; Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Documentary History. Greenwood Press. 1998.

مصادر ثانوية

سـيـر

- Best, Gary Dean. The Politics of American Individualism: Herbert Hoover in Transition, 1918-1921 (1975)

- Bornet, Vaughn Davis, An Uncommon President. In: Herbert Hoover Reassessed. (1981), pp. 71-88.

- Burner, David. Herbert Hoover: A Public Life. (1979). one-volume scholarly biography.

- Gelfand, Lawrence E. ed., Herbert Hoover: The Great War and Its Aftermath, 1914-1923 (1979).

- Hatfield, Mark. ed. Herbert Hoover Reassessed (2002).

- Hawley, Ellis. Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce: Studies in New Era Thought and Practice (1981). A major reinterpretation.

- Hawley, Ellis. Herbert Hoover and the Historians (1989).

- Hoff-Wilson, Joan. Herbert Hoover: Forgotten Progressive. (1975). short biography

- Lloyd, Craig. Aggressive Introvert: A Study of Herbert Hoover and Public Relations Management, 1912-1932 (1973).

- Nash, George H. The Life of Herbert Hoover: The Engineer 1874-1914 (1983), the definitive scholarly biography.

- Life of Herbert Hoover: The Humanitarian, 1914-1917 (1988), vol. 2.

- The Life of Herbert Hoover: Master of Emergencies, 1917-1918 (1996), vol. 3

- Nash, Lee, ed. Understanding Herbert Hoover: Ten Perspectives (1987).

- Smith, Gene. The Shattered Dream: Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression (1970).

- Smith, Richard Norton. An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover, (1987) full-length scholarly biography.

- Walch, Timothy. ed. Uncommon Americans: The Lives and Legacies of Herbert and Lou Henri Hoover Praeger, 2003.

دراسات أكاديمية

- Long annotated bibliography via University of Virginia.

- Barber, William J. From New Era to New Deal: Herbert Hoover, the Economists, and American Economic Policy, 1921-1933. (1985).

- Barry, John M. Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America (1998), Hoover played a major role.

- Britten, Thomas A. "Hoover and the Indians: the Case for Continuity in Federal Indian Policy, 1900-1933" Historian 1999 61(3): 518-538. ISSN 0018-2370

- Calder, James D. The Origins and Development of Federal Crime Control Policy: Herbert Hoover's Initiatives Praeger, 1993.

- Carcasson, Martin. "Herbert Hoover and the Presidential Campaign of 1932: the Failure of Apologia" Presidential Studies Quarterly 1998 28(2): 349-365.

- Clements, Kendrick A. Hoover, Conservation, and Consumerism: Engineering the Good Life. U. Press of Kansas, 2000.

- DeConde, Alexander. Herbert Hoover's Latin American Policy. (1951).

- Dodge, Mark M., ed. Herbert Hoover and the Historians. (1989).

- Doenecke, Justus D. "Anti-Interventionism of Herbert Hoover" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Summer 1987, 8(2), pp. 311-340. online version

- Fausold, Martin L. The Presidency of Herbert C. Hoover. (1985) standard scholarly overview.

- Fausold Martin L. and George Mazuzan, eds. The Hoover Presidency: A Reappraisal (1974).

- Ferrell, Robert H. American Diplomacy in the Great Depression: Hoover-Stimson Foreign Policy, 1929-1933. (1957).

- Goodman, Mark and Gring, Mark. "The Ideological Fight over Creation of the Federal Radio Commission in 1927" Journalism History 2000 26(3): 117-124.

- Hamilton, David E. From New Day to New Deal: American Farm Policy from Hoover to Roosevelt, 1928-1933. (1991).

- Hart, David M. "Herbert Hoover's Last Laugh: the Enduring Significance of the 'Associative State' in the United States." Journal of Policy History 1998 10(4): 419-444.

- Hawley, Ellis. "Herbert Hoover, the Commerce Secretariat, and the Vision of an 'Associative State,' 1921-1928." Journal of American History 61 (1974): 116-140.

- Houck, Davis W. "Rhetoric as Currency: Herbert Hoover and the 1929 Stock Market Crash" Rhetoric & Public Affairs 2000 3(2): 155-181. ISSN 1094-8392

- Hutchison, Janet. "Building for Babbitt: the State and the Suburban Home Ideal" Journal of Policy History 1997 9(2): 184-210

- Lichtman, Allan J. Prejudice and the Old Politics: The Presidential Election of 1928 (1979).

- Lisio, Donald J. The President and Protest: Hoover, MacArthur, and the Bonus Riot, 2d ed. (1994).

- Lisio, Donald J. Hoover, Blacks, and Lily-whites: A Study of Southern Strategies (1985)

- Malin, James C. The United States after the World War. 1930. extensive coverage of Hoover's Commerce Dept. policies

- Olson, James S. Herbert Hoover and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, 1931-1933 (1977).

- Robinson, Edgar Eugene and Vaughn Davis Bornet. Herbert Hoover: President of the United States. (1976).

- Romasco, Albert U. The Poverty of Abundance: Hoover, the Nation, the Depression (1965).

- Schwarz, Jordan A. The Interregnum of Despair: Hoover, Congress, and the Depression. (1970). Hostile to Hoover.

- Stoff, Michael B. "Herbert Hoover: 1929-1933." The American Presidency: The Authoritative Reference. New York, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company (2004), 332-343.

- Sobel, Robert Herbert Hoover and the Onset of the Great Depression 1929-1930 (1975).

- Tracey, Kathleen. Herbert Hoover—A Bibliography. His Writings and Addresses (1977).

- Wilbur, Ray Lyman, and Arthur Mastick Hyde. The Hoover Policies. (1937). In depth description of his administration by two cabinet members.

- Wueschner, Silvano A. Charting Twentieth-Century Monetary Policy: Herbert Hoover and Benjamin Strong, 1917-1927. Greenwood, 1999.

انظر أيضاً

- Great Depression in the United States

- List of presidents of the United States

- Progressive Era

- Roaring Twenties

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ Levinson, Martin H. (2011). "Indexing and Dating America's 'Worst' Presidents". ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 68 (2): 147–155. ISSN 0014-164X. JSTOR 42579110.

- ^ Merry, Robert W. (2021-01-03). "RANKED: Historians Don't Think Much of These Five U.S. Presidents". The National Interest (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ أ ب ت Lemann, Nicholas (October 23, 2017). "Hating on Herbert Hoover". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ Biography, Miller center, October 4, 2016, http://millercenter.org/president/hoover/essays/biography/1

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Fausold 1985, p. 34.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 81–82.

- ^ See generally Nancy Beck Young, Lou Henry Hoover: Activist First Lady (University Press of Kansas, 2005)

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E., "The Wrong Man at the Wrong Time", American Heritage, Summer 2009

- ^ Homelessness: A Documentary and Reference Guide, ABC-CLIO, 2012, pp. 140–, ISBN 9780313377006, http://books.google.com/books?id=PlhJUhELTbwC&pg=PA140

- ^ "The Great Depression and New Deal"

- ^ Social history of the United States, Volume 1, Brian Greenberg, Linda S. Watts

- ^ Hoover, Herbert. The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, 1952[استشهاد ناقص]

- ^ The Depression Begins: President Hoover Takes Command. Mises.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-14.

- ^ J.M. Clark, "Public Works and Unemployment," American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings (May, 1930): 15ff.

- ^ Harris Gaylord Warren, Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression (New York: Oxford University Press, 1959), p. 175.

- ^ The Depression Begins: President Hoover Takes Command. Mises.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-14.

- ^ Banks. http://mises.org/rothbard/agd/chapter11.asp#inflation_program

- ^ Ohanian, Lee. "Hoover's pro-labor stance spurred Great Depression", University of California, August 2009

- ^ DeLong, J. Bradford (August 29, 2009), "Herbert Hoover: A Working Class Hero Is Something to Be". Retrieved March 3, 2010

- ^ Aaron Bernard Wildavsky; Michael J. Boskin (1982), The Federal Budget: Economics and Politics, Transaction Publishers, p. 4, ISBN 9781412823494, http://books.google.com/books?id=SBMUaGo7PacC&pg=PA4

- ^ Kumiko Koyama, "The Passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act: Why Did the President Sign the Bill?" Journal of Policy History (2009) 21#2 pp. 163–86

- ^ "Hoover Moratorium", u-s-History.com

- ^ "Lausanne Conference", u-s-History.com

- ^ "Reconstruction Finance Corporation", EH.net Encyclopedia

- ^ "What Caused the Great Depression of the 1930s", Shambhala.com

- ^ "Great Depression in the United States", Microsoft Encarta Archived November 1, 2009

- ^ James Ciment. Encyclopedia of the Great Depression and the New Deal. Sharpe Reference, 2001. Originally from the University of Michigan. p. 396

- ^ in The Check Tax: Fiscal Folly and The Great Monetary Contraction Journal of Economic History, 57(4), December 1997, 859-78; [

- ^ Friedrich, Otto (February 1, 1982). "F.D.R.'s Disputed Legacy". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ 1930s Engineering, Andrew J. Dunar on PBS

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 104105.

- ^ أ ب Kennedy 1999, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Harris Gaylord Warren, Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression (New York: Oxford University Press, 1959), p. 175.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 93–97.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 399–402, 414.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 414–415.

- ^ Kumiko Koyama, "The Passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act: Why Did the President Sign the Bill?" Journal of Policy History (2009) 21#2 pp. 163–86

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Kennedy 1999, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Kennedy 1999, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Kennedy 1999, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Eichengreen & Temin 2000, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 441–444, 449.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 450–452.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 485–486.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Carcasson 1998, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Cabanes, Bruno (2014). The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918–1924. Cambridge University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-107-02062-7.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 457–459.

- ^ أ ب Fausold 1985, pp. 162–166.

- ^ Olson 1972, pp. 508–511.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Rappleye 2016, pp. 309.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 483–484.

- ^ Rappleye 2016, p. 303.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 472, 488–489.

- ^ Ippolito, Dennis S. (2012). Deficits, Debt, and the New Politics of Tax Policy. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-139-85157-2.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Lisio, Donald J. Hoover, Blacks, & Lily-Whites: A Study of Southern Strategies, University of North Carolina Press, 1985 (excerpt)

- ^ Garcia 1980, pp. 471–474.

- ^ Garcia 1980, pp. 462–464.

- ^ Garcia 1980, pp. 464–465.

- ^ Garcia 1980, pp. 465–467.

- ^ Garcia 1980, pp. 476–477.

- ^ Rappleye 2016, p. 247.

- ^ Hoffman 1973, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Hoffman 1973, pp. 208, 217–218.

- ^ أ ب ت Gratton, Brian; Merchant, Emily (December 2013). "Immigration, Repatriation, and Deportation: The Mexican-Origin Population in the United States, 1920-1950" (PDF). Vol. 47, no. 4. The International migration review. pp. 944–975.

- ^ Johnson 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Johnson 2005, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Johnson 2005, p. 6.

- ^ "The Ordeal of Herbert Hoover". National Archives. 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 372–373.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 433–435.

- ^ Kyvig, David E. (1979). Repealing National Prohibition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. p. 49.

- ^ Huckabee, David C. (September 30, 1997). "Ratification of Amendments to the U.S. Constitution" (PDF). Congressional Research Service reports. Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 183–186.

- ^ Fausold 1985, p. 58.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 479–480.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 175–176.

- ^ أ ب Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 117–119.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Current, Richard N. (1954). "The Stimson Doctrine and the Hoover Doctrine". The American Historical Review. 59 (3): 513–542. doi:10.2307/1844715. JSTOR 1844715.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Dickson, Paul; Allen, Thomas B. (February 2003). "Marching on History". Smithsonian. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Carcasson 1998, pp. 353.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 138–140.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 211–212.

- ^ "Prohibition After the 1932 Elections" CQ Researcher

- ^ Herbert Brucker, "How Long, O Prohibition?" The North American Review, 234#4 (1932), pp. 347–357. online

- ^ Carcasson 1998, pp. 359.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy (November 10, 2008). "When New President Meets Old, It's Not Always Pretty". Time. Archived from the original on November 11, 2008.

- ^ Carcasson 1998, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Fausold 1985, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 142.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 147–149.

- ^ أ ب Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 555–557.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 147–151.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Short, Brant (1991). "The Rhetoric of the Post-Presidency: Herbert Hoover's Campaign against the New Deal, 1934–1936". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 21 (2): 333–350. JSTOR 27550722.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 147–154.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 558–559.

- ^ Kosner, Edward (October 28, 2017). "A Wonder Boy on the Wrong Side of History". The Wall Street Journal. New York City.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 152–154.

- ^ Katznelson, Ira (2013). Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of our Time. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-0-87140-450-3. OCLC 783163618.

- ^ Whyte 2017, p. 565.

- ^ Jeansonne 2016, pp. 328–329.

- ^ "The Great Humanitarian: Herbert Hoover's Food Relief Efforts". Cornell College. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Churchill, Winston (August 20, 1940). "'The Few' Speech". International Churchill Society. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "FOREIGN TRADE: Amtorg's Spree". Time. February 19, 1940. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010.

- ^ "THE CONGRESS: Sounding Trumpets". Time. January 29, 1940. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010.

- ^ Robinson, Edgar Eugene (1973). "Hoover, Herbert Clark". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. pp. 676–77.

- ^ Whyte 2017, p. 572.

- ^ Cohen, Jared (April 9, 2019). Accidental presidents : eight men who changed America (First hardcover ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-5011-0982-9. OCLC 1039375326.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Beschloss, Michael R. (2002). The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7432-4454-1.

- ^ UN Chronicle (March 18, 1947). "The Marshall Plan at 60: The General's Successful War on Poverty". The United Nations. Archived from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Shephard, Roy J. (2014). An Illustrated History of Health and Fitness, from Pre-History to our Post-Modern World. New York City: Axel Springer SE. p. 782.

- ^ "National Press Club Luncheon Speakers, Herbert Hoover, March 10, 1954". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man, (1984) pp 371–380.

- ^ Christopher D. McKenna, "Agents of adhocracy: management consultants and the reorganization of the executive branch, 1947–1949." Business and Economic History (1996): 101–111.

- ^ أ ب Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 587–588.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 592–594.

- ^ Herbert Hoover, The Crusade Years, 1933–1955: Herbert Hoover's Lost Memoir of the New Deal Era and Its Aftermath, edited by George H. Nash, (Hoover Institution Press, 2013) p 13.

- ^ Whyte 2017, p. 595.

- ^ Whyte 2017, p. 592.