بروكسل

بروكسل (Brussels،[أ] officially the Brussels-Capital Region,[ب][12][13] هي عاصمة بلجيكا. ]].[14] تعد عاصمة غير رسمية للاتحاد الأوروبي لكثرة مقار الاتحاد فيها ، منها: اللجنة الأوروبية ومجلس الاتحاد الأوروبي (مجلس الوزراء). تبلغ مساحة بروكسل حوالي 32 كم مربع ويبلغ عدد سكانها 853, 142 نسمة (احصاءات يناير 2005). يبلغ عدد سكان مقاطعة بروكسل حوالي مليون نسمة.

بروكسل خامسة أكبر مدينة في بلجيكا، ولكنها مع ضواحيها، تمثل أكبر منطقة حضرية في البلاد. وبروكسل مركز للنشاط الاقتصادي والسياسي الدولي. اتخذت عديد من المنظمات العالمية ـ من ضمنها الاتحاد الأوروبي ومنظمة حلف شمال الأطلسي (الناتو) ـ مكاتب رئيسية في المدينة، أو قريبًا منها.

تعتبر بروكسل العاصمة وهي تستعمل لغتين رسميتين؛ هما الفرنسية والهولندية في مجالات التعليم والتفاهم، بيد أن الفرنسية تستعمل لدى غالبية الشعب، ويطلق الاسم براسل على العاصمة في اللغة الهولندية، وبروكسل في اللغة الفرنسية.

التسمية

جاء إسم بروكسل من الكلمة الهولندية القديمة Bruocsella ، والتي تعني (bruoc) الأهوار وكلمة (sella) وتعني الوطن أي الوطن في الأهوار.

التاريخ

التاريخ المبكر

The history of Brussels is closely linked to that of Western Europe. Traces of human settlement go back to the Stone Age, with vestiges and place-names related to the civilisation of megaliths, dolmens and standing stones (Plattesteen near the Grand-Place/Grote Markt and Tomberg in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, for example). During late antiquity, the region was home to Roman occupation, as attested by archaeological evidence discovered on the current site of Tour & Taxis, north-west of the Pentagon (Brussels' city centre).[15][16] Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, it was incorporated into the Frankish Empire.

According to local legend, the origin of the settlement which was to become Brussels lies in Saint Gaugericus' construction of a chapel on an island in the river Senne around 580.[17] The official founding of Brussels is usually said to be around 979, when Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine, transferred the relics of the martyr Saint Gudula from Moorsel (located in today's province of East Flanders) to Saint Gaugericus' chapel. When Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor, appointed the same Charles to become Duke of Lower Lotharingia in 977,[18] Charles ordered the construction of the city's first permanent fortification, doing so on that same island.

العصور الوسطى

Lambert I, Count of Louvain, gained the County of Brussels around 1000 by marrying Charles' daughter. Because of its location on the banks of the Senne, on an important trade route between the Flemish cities of Bruges and Ghent, and Cologne in the Kingdom of Germany, Brussels became a commercial centre specialised in the textile trade. The town grew quite rapidly and extended towards the upper town (Treurenberg, Coudenberg and Sablon/Zavel areas), where there was a reduced risk of floods. As the town grew to a population of around 30,000, the surrounding marshes were drained to allow for further expansion. In 1183, the Counts of Leuven became Dukes of Brabant. Brabant, unlike the county of Flanders, was not fief of the king of France but was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire.

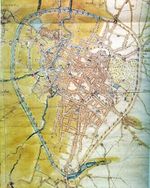

In the early 13th century, the first walls of Brussels were built[19] and after this, the city grew significantly. Around this time, work began on what is now the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula (1225), replacing an older Romanesque church.[20] To let the city expand, a second set of walls was erected between 1356 and 1383. Traces of these walls can still be seen; the Small Ring, a series of boulevards bounding the historical city centre, follows their former course.

عصر النهضة

In the 14th century, the marriage between heiress Margaret III, Countess of Flanders, and Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, produced a new Duke of Brabant of the House of Valois, namely Anthony, their son.[21] In 1477, the Burgundian duke Charles the Bold perished in the Battle of Nancy.[22] Through the marriage of his daughter Mary of Burgundy (who was born in Brussels) to Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, the Low Countries fell under Habsburg sovereignty.[23] Brabant was integrated into this composite state, and Brussels flourished as the Princely Capital of the prosperous Burgundian Netherlands, also known as the Seventeen Provinces. After the death of Mary in 1482, her son Philip the Handsome succeeded as Duke of Burgundy and Brabant.

Philip died in 1506, and he was succeeded by his son Charles V who then also became King of Spain (crowned in the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula) and even Holy Roman Emperor at the death of his grandfather Maximilian I in 1519. Charles was now the ruler of a Habsburg Empire "on which the sun never sets" with Brussels serving as one of his main capitals.[2][24] It was in the Coudenberg Palace that Charles V was declared of age in 1515, and it was there in 1555 that he abdicated all of his possessions and passed the Habsburg Netherlands to King Philip II of Spain.[25] This palace, famous all over Europe, had greatly expanded since it had first become the seat of the Dukes of Brabant, but it was destroyed by fire in 1731.[26][27]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Brussels was a centre for the lace industry. In addition, Brussels tapestry hung on the walls of castles throughout Europe.[28][29] In 1695, during the Nine Years' War, King Louis XIV of France sent troops to bombard Brussels with artillery. Together with the resulting fire, it was the most destructive event in the entire history of Brussels. The Grand-Place was destroyed, along with 4,000 buildings—a third of all the buildings in the city. The reconstruction of the city centre, effected during subsequent years, profoundly changed its appearance and left numerous traces still visible today.[30]

During the War of the Spanish Succession in 1708, Brussels again sustained a French attack, which it repelled. Following the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, Spanish sovereignty over the Southern Netherlands was transferred to the Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg. This event started the era of the Austrian Netherlands. Brussels was captured by France in 1746, during the War of the Austrian Succession,[31] but was handed back to Austria three years later. It remained with Austria until 1795, when the Southern Netherlands were captured and annexed by France, and the city became the chef-lieu of the department of the Dyle.[32][33] The French rule ended in 1815, with the defeat of Napoleon on the battlefield of Waterloo, located south of today's Brussels-Capital Region.[34] With the Congress of Vienna, the Southern Netherlands joined the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, under King William I of Orange. The former Dyle department became the province of South Brabant, with Brussels as its capital.

الثورة

In 1830, the Belgian Revolution began in Brussels, after a performance of Auber's opera La Muette de Portici at the Royal Theatre of La Monnaie.[35] The city became the capital and seat of government of the new nation. South Brabant was renamed simply Brabant, with Brussels as its administrative centre. On 21 July 1831, Leopold I, the first King of the Belgians, ascended the throne,[36] undertaking the destruction of the city walls and the construction of many buildings.[37]

Following independence, Brussels underwent many more changes. It became a financial centre, thanks to the dozens of companies launched by the Société Générale de Belgique. The Industrial Revolution and the opening of the Brussels–Charleroi Canal in 1832 brought prosperity to the city through commerce and manufacturing.[38][39] The Free University of Brussels was established in 1834 and Saint-Louis University in 1858. In 1835, the first passenger railway built outside England linked the municipality of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean with Mechelen.[40]

During the 19th century, the population of Brussels grew considerably; from about 80,000 to more than 625,000 people for the city and its surroundings. The Senne had become a serious health hazard, and from 1867 to 1871, under the tenure of the city's then-mayor, Jules Anspach, its entire course through the urban area was completely covered over.[41] This allowed urban renewal and the construction of modern buildings of Haussmann-esque style along grand central boulevards, characteristic of downtown Brussels today.[42] Buildings such as the Brussels Stock Exchange (1873), the Palace of Justice (1883) and Saint Mary's Royal Church (1885) date from this period. This development continued throughout the reign of King Leopold II. The International Exposition of 1897 contributed to the promotion of the infrastructure.[43] Among other things, the Palace of the Colonies, today's Royal Museum for Central Africa, in the suburb of Tervuren, was connected to the capital by the construction of an 11 km-long (6.8 mi) grand alley.

Brussels became one of the major European cities for the development of the Art Nouveau style in the 1890s and early 1900s.[44] The architects Victor Horta, Paul Hankar, and Henry van de Velde, among others, were known for their designs, many of which survive today.[45]

التاريخ الحديث

During the 20th century, the city hosted various fairs and conferences, including the Solvay Conference on Physics and on Chemistry, and three world's fairs: the Brussels International Exposition of 1910, the Brussels International Exposition of 1935 and the 1958 Brussels World's Fair (Expo 58).[43] During World War I, Brussels was an occupied city. It escaped large-scale destruction,[46] although the interwar period would still see a significant amount of (re)construction.[ت][47] In November 1918, after the German Revolution had broken out, Brussels was embroiled in street battles between revolutionary soldiers who wanted to end the occupation and their imperialist counterparts; additionally, explosives left behind by retreating German troops damaged infrastructure and around 2,300 houses.[48]

During World War II, Brussels was occupied by German forces once again. While it was again spared major damage, a deadly bombing took place on 7 September 1943. It was carried out by the American airforce which had tried to aim at SABCA facilities in Haren, but accidentally struck an area in Ixelles, killing 282 civilians.[49] The city was liberated by the British Guards Armoured Division on 3 September 1944. Brussels Airport, in the suburb of Zaventem, traces its roots to a German military airport that was built in nearby Melsbroek.[50]

After World War II, Brussels underwent extensive modernisation. The construction of the North–South connection, linking the main railway stations in the city, was completed in 1952, while the first premetro (underground tram) service was launched in 1969,[51] and the first Metro line was opened in 1976.[52] Starting from the early 1960s, Brussels became the de facto capital of what would become the European Union (EU), and many modern offices were built. Development was allowed to proceed with little regard to the aesthetics of newer buildings, and numerous architectural landmarks were demolished to make way for newer buildings that often clashed with their surroundings, giving name to the process of Brusselisation.[53][54]

المعاصر

The Brussels-Capital Region was formed on 18 June 1989, after a constitutional reform in 1988.[55] It is one of the three federal regions of Belgium, along with Flanders and Wallonia, and has bilingual status.[12][13] The yellow iris is the emblem of the region (referring to the presence of these flowers on the city's original site) and a stylised version is featured on its official flag.[56]

In the 21st century, Brussels has become an important venue for international events. In 2000, it was named European Capital of Culture alongside eight other European cities.[57] In 2013, the city was the site of the Brussels Agreement.[58] In 2014, it hosted the 40th G7 summit,[59] and in 2017, 2018 and 2021 respectively the 28th, 29th and 31st NATO Summits.[60][61][62]

On 22 March 2016, three coordinated nail bombings were detonated by ISIL in Brussels—two at Brussels Airport in Zaventem and one at Maalbeek/Maelbeek metro station—resulting in 32 victims and three suicide bombers killed, and 330 people were injured. It was the deadliest act of terrorism in Belgium.[63][64][65][66]

الجغرافيا

المناخ

| متوسطات الطقس لبروكسل | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | |

| متوسط العظمى °م (°ف) | 5 (41) | 6 (43) | 10 (50) | 14 (57) | 18 (64) | 20 (68) | 23 (73) | 23 (73) | 19 (66) | 14 (57) | 9 (48) | 6 (43) | |

| متوسط الصغرى °م (°ف) | 1 (34) | 2 (36) | 4 (39) | 6 (43) | 9 (48) | 12 (54) | 14 (57) | 14 (57) | 12 (54) | 8 (46) | 5 (41) | 3 (37) | |

| هطول الأمطار cm (بوصة) | 5.77 (2.3) | 5.2 (2) | 5.11 (2) | 3.88 (1.5) | 4.42 (1.7) | 5.52 (2.2) | 6.23 (2.5) | 5.61 (2.2) | 5.02 (2) | 5.31 (2.1) | 5.6 (2.2) | 6.22 (2.4) | |

| المصدر: MSN Weather [67] 2007-10-04 | |||||||||||||

مركز سياسي

عاصمة بلجيكا

مدينة بروكسل

مركز دولي

الاتحاد الأوروبي

الثقافة

المعمار

الفنون

المعالم السياحية

گراند پلاس أو الميدان الكبير هو أهم معلم في المدينة، حيث يقع عليه مبنى بلدية بروكسل وكنيسة القديس ميخائيل. يوجد في منطقة لاكن بناء الأتوميوم، الذي بني عام 1958 خصيصا للمعرض الدولي الاكسبو الذي أقيم في بروكسل آنذاك، كان من المفروض إزالته بعد إنتهاء مدة المعرض ولكن تم الإبقاء عليه إلى يومنا هذا وأصبح أحد معالم المدينة الرئيسية. هناك عدة مسارح ومتاحف مهمة في بروكسل، أشهرها مسرح دي لا مونيه (Théâtre de la Monnaie/Muntschouwburg)، حيث تقام فيه عروض أوبرا أيضا. تعتبر بروكسل عاصمة مجلات الرسوم المتحركة (كوميك) على المستوى الأوروبي، حيث ساهم الرسامون ودور النشر البلجيك في ابتكار شخصيات خيالية مثل لاكي لوك وتان تان وكوبيتوس وغاستون ومارسوبيلامي، التي لاقت رواجا عالميا. تشتهر المدينة أيضا بالشوكولاتة وخاصة النوع الداكن منها وأحجار الصدف (حلويات). يفتخر البلجيك بأنهم أول من أوجد أكلة البطاطس المقلية، التي ساهم بيعها في شوارع بروكسل بإنتشارها عالميا. تصنع في المدينة عدة ماركات وأنواع من الجعة، أشهرها هوغاردين (Hoegaarden) وليفه (Leffe) ودوفل (Duvel).

فن الطهي

التقسيم الإداري

تنقسم مدينة بروكسل إلى سبعة مناطق إدارية:

- بروكسل-هارينBrüssel-Haren

- بروكسل-لاكن Brüssel-Laeken

- بروكسل-نيدر-أوفر-هيمبيك Brüssel-Neder-Over-Heembeek

- بروكسل-بينتاغون Brüssel-Quartier Louise

- بروكسل-كوارتير-لواز Brüssel-Quartier Louise

- بروكسل-اسباس-نورد Brüssel-Espace Nord

- بروكسل-نورد-است Brüssel-Nord-Est

الإقتصاد والبنية التحتية

تعد بروكسل مركز اقتصادي مهم في أوروبا. تملك شركة صناعة السيارات فولكس فاغن مصنعا في المدينة، الذي يقوم بتشطيب موديل فولكس فاغن غولف. مقار الاتحاد الأوروبي في المدينة كانت أحد أسباب اتخاذ الكثير من الشركات العالمية من المدينة مقرا لها أيضا.

ترتبط المدينة بشبكة السكك الحديدية البلجيكة، كما أن هناك خطوط مباشرة لكل من أمستردام وباريس وكولونيا ولندن. أهم محطات القطار هي محطات بروكسل-المركزية وبروكسل-الشمالية و بروكسل-الجنوبية. هناك ثلاثة خطوط لشبكة المترو و16 خط ترام وحوالي 50 خط باص. يقع مطار بروكسل الدولي على بعد 12 كم شرق مركز المدينة.

اللغات

التعليم

جامعات ومعاهد بروكسل العليا:

- جامعة بروكسل الحرة Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB)

- جامعة فرييه بروكسل the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB)

- كلية سانت لويس الجامعية Facultés Universitaires Saint Louis (FUSL)

- جامعة بروكسل الكاثوليكية Katholieke Universiteit Brussel (KUB)

- الأكاديمية العسكرية الملكية

- جامعة لوفان الكاثوليكية Université catholique de Louvain (UCL) (جزء منها يقع في بروكسل)

النقل

الإتصالاات

النقل العام

شبكة الطرق

مدن شقيقة

ترتبط بروكسل بعلاقات مع 14 مدينة شقيقة:

انظر أيضا

وصلات خارجية

- Brussels-Capital Region, official site

- بروكسل travel guide from Wikitravel

- Interactive map

- Interactive 360 virtual tour

- Virtual tour 360° From Brussels !

المصادر

- ^ Demey 2007.

- ^ أ ب "How Brussels became the capital of Europe 500 years ago". The Brussels Times. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةComic - ^ "be.STAT". bestat.statbel.fgov.be. Archived from the original on 24 September 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Mini-Bru | IBSA". ibsa.brussels. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Structuur van de bevolking | Statbel". Statbel.fgov.be (in الهولندية). Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ EMN Belgium (2025-06-12). "Belgium's population shows increasing diversity, with 36% having foreign background, according to Statbel". EMN Belgium. Retrieved 2025-09-02.

- ^ "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- ^ أ ب The Belgian Constitution (PDF). Brussels: Belgian House of Representatives. May 2014. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

Article 3: Belgium comprises three Regions: the Flemish Region, the Walloon Region and the Brussels Region. Article 4: Belgium comprises four linguistic regions: the Dutch-speaking region, the French-speaking region, the bilingual region of Brussels-Capital and the German-speaking region.

- ^ أ ب "Brussels-Capital Region / Creation". Centre d'Informatique pour la Région Bruxelloise [Brussels Regional Informatics Center]. 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

Since 18 June 1989, the date of the first regional elections, the Brussels-Capital Region has been an autonomous region comparable to the Flemish and Walloon Regions.

(All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) - ^ Welcome to Brussels

- ^ "Bruxelles: des vestiges romains retrouvés sur le site de Tour et Taxis". RTBF Info (in الفرنسية). 6 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "Les Romains de Tour & Taxis — Patrimoine – Erfgoed". patrimoine.brussels (in الفرنسية). Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ State 2004, p. 269.

- ^ Riché 1983, p. 276.

- ^ "Zo ontstond Brussel" [This is how Brussels originated] (in الهولندية). Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie [Commission of the Flemish Community in Brussels]. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007.

- ^ Brigode 1938, p. 185–215.

- ^ Blockmans & Prevenier 1999, p. 30–31.

- ^ Kirk 1868, p. 542.

- ^ Armstrong 1957, p. 228.

- ^ Jenkins, Everett Jr. (7 May 2015). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500–1799): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. McFarland. ISBN 9781476608891. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wasseige 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 222.

- ^ Wasseige 1995, p. 6–7.

- ^ Souchal, Geneviève (ed.), Masterpieces of Tapestry from the Fourteenth to the Sixteenth Century: An Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 108, 1974, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), Galeries nationales du Grand Palais (France), ISBN 0870990861, 9780870990861, google books Archived 29 أكتوبر 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Campbell, ed. Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art 2002.

- ^ Culot et al. 1992.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 753.

- ^ Oudiette 1804.

- ^ Duvergier 1835, p. 300.

- ^ Galloy & Hayt 2006, p. 86–90.

- ^ Slatin 1979, p. 53–54.

- ^ Pirenne 1948, p. 30.

- ^ Demey 2009, p. 96.

- ^ Charruadas 2005.

- ^ Demey 2009, p. 96–97.

- ^ Wolmar 2010, p. 18–20.

- ^ Demey 1990, p. 65.

- ^ Eggericx 1997, p. 5.

- ^ أ ب Schroeder-Gudehus & Rasmussen 1992.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:6 - ^ "Cahier pédagogique : 14–18. Bruxelles occupée" (PDF). Erfgoedklassen. 2017. p. 49. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ Jaumain, Serge; Jourdain, Virginie; et al. (2016). "Sur les traces de la Première Guerre mondiale à Bruxelles : Note de synthèse BSI". Brussels Studies. 102. doi:10.4000/brussels.1403. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ Realfonzo, Ugo (11 November 2022). "Brussels in 1918: Occupation, revolution and the Armistice". The Brussels Times. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ Difficile, Luana (18 January 2025). "Jouw vraag over Brussel: wat was het grootste bombardement op Brussel?". VRT NWS. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ Van Parijs, Philippe (8 July 2016). "Brussels City Airport: from curse to blessing?". The Brussels Times. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ "STIB – La STIB de 1960 à 1969" [STIB – STIB from 1960 to 1969] (in الفرنسية). STIB. 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ^ "STIB – Historique de la STIB de 1970 à 1979" [STIB – History of STIB from 1970 to 1979] (in الفرنسية). STIB. 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ^ State 2004, p. 51–52.

- ^ Stubbs & Makaš 2011, p. 121.

- ^ "The Brussels-Capital Region". Belgium.be. 2012-02-01. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- ^ "LOI – WET". ejustice.just.fgov.be (in الفرنسية). Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "Association of European Cities of Culture of the Year 2000". Krakow the Open City. 17 August 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ srbija.gov.rs. "Brussels Agreement". srbija.gov.rs. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "Brussels G7 summit, Brussels, 04-05/06/2014 – Consilium". European Council. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ "NATO Summit 2017". state.gov. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ "NATO Secretary General announces dates for 2018 Brussels Summit". nato.int. 20 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ "NATO Secretary General announces date of the 2021 Brussels Summit". nato.int. 22 April 2021. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie (22 March 2016). "Brussels attacks timeline: How bombings unfolded at airport and Metro station". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Brussels explosions: What we know about airport and metro attacks". BBC News. 9 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Victims of the Brussels attacks". BBC News. 15 April 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Brussels attacks: 'Let us dare to be tender,' says king on first anniversary". The Guardian. 22 March 2017. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "MSN Weather".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help) - ^ (Dutch)”Taalgebruik in Brussel en de plaats van het Nederlands. Enkele recente bevindingen”, Rudi Janssens, Brussels Studies, Nummer 13, 7 January 2008 (see page 4).

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الهولندية-language sources (nl)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Articles containing هولندية-language text

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- صفحات تستخدم جدول مستوطنة بقائمة محتملة لصفات المواطن

- Pages with empty portal template

- بروكسل

- عواصم في الإتحاد الأوروبي

- Brabant

- Regions of Belgium

- Regions of Europe with multiple official languages

- Enclaves and exclaves

- Countries and territories where French is an official language

- Autonomous regions

- NUTS 1 statistical regions of the European Union

- Populated places established in the 1st millennium