قوة التجريدة المصرية

| Egyptian Expeditionary Force قوة التجريدة المصرية | |

|---|---|

| نشطة | 1916–19 |

| البلد | |

| الاشتباكات | الحرب العالمية الأولى |

| القادة | |

| أبرز القادة | أرشيبالد مري (1916–17) إدموند اللنبي (1917–19) |

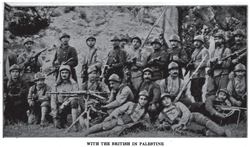

قوة التجريدة المصرية إنگليزية: Egyptian Expeditionary Force تشكلت في مارس 1916 لتقود القوات العسكرية المتنامية من المملكة المتحدة وباقي أحزاء الامبراطورية البريطانية في مصر أثناء الحرب العالمية الأولى للدفاع عن مصر في وجه حملتي ترعة السويس الأولي والثانية التي شنهما الجيش العثماني السابع بالمشاركة بقيادات ألمانية.

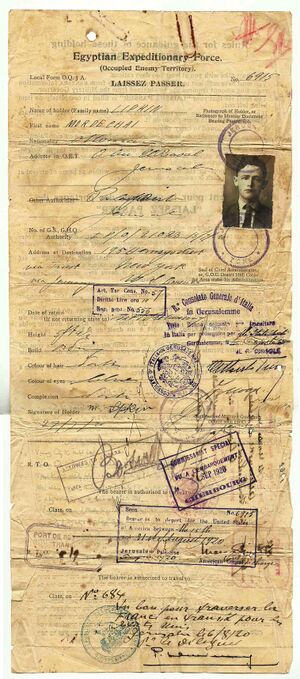

اُرسل إدموند اللنبي إلى مصر ليكون القائد الأعلى لقوة التجريدة المصرية في 27 يونيو 1917، ليحل محل السير أرشيبولد ماري. من أول أعمال اللنبي كان دعم جهود لورنس العرب بين العرب ب 20,000 جنيه استرليني في الشهر.

تطور دور القوة من الدفاع عن مصر إلى غزو فلسطين الذي تضمن: الاستيلاء على بئر سبع وغزة في أكتوبر-نوفمبر 1917 (انظر معركة غزة الثالثة)، ودخول القدس في 11 ديسمبر 1917، وحملة ألنبي الناجحة في عام 1918، التي نجحت في هزيمة الأتراك في مجدو، والإستيلاء على دمشق وبيروت وحلب. أدت نجاحات القوة في النهاية لخروج تركيا من الحرب وفرض الانتداب البريطاني على فلسطين.

بعد اعادة هيكلة قواته النظامية استطاع اللنبي النصر في معركة غزة الثالثة (31 أكتوبر - 7 نوفمبر 1917) و ذلك بمفاجأة المدافعين عنها بهجمة على بير سبع.

انتصرت التجريدة بقيادة اللنبي على العثمانيين في معركة مجدو في سبتمبر 1918. وكان الانتصار قاصماً للعثمانيين وحاسماً للجبهة الجنوبية في الحرب العالمية الأولى.

During the Stalemate in Southern Palestine from April to October 1917, Murray consolidated the EF's position and in June General Edmund Allenby took command and began preparations to take the offensive, employing manoeuvre warfare. He reorganised the force into the XX Corps, XXI Corps and Desert Mounted Corps (formerly the Desert Column).[1][2] On 31 October two corps captured Beersheba defended by the Ottoman III Corps (which had fought at Gallipoli), which weakened their defences stretching almost continually from Gaza to Beersheba. Subsequently the Battle of Tel el Khuweilfe, the Third Battle of Gaza and the Battle of Hareira and Sheria forced an Ottoman withdrawal from Gaza on the night of 6/7 November and the beginning of the pursuit to Jerusalem. During the subsequent operations, about fifty mi (80 km) of Ottoman territory, was captured as a result of the EEF victories at the Battle of Mughar Ridge (10–14 November) and the Battle of Jerusalem (17 November – 30 December.)[3]

Serious losses on the Western Front in March 1918 during the German spring offensive, forced the British to divert forces from the EEF. During this time, two unsuccessful attacks were made, the First Transjordan attack on Amman and the Second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt to capture Es Salt, in March and April 1918, before Allenby's force resumed the offensive, again employing manoeuvre warfare at the Battle of Megiddo. The successful infantry attacks of the Battle of Tulkarm and the Battle of Tabsor created gaps in the Ottoman defences, enabling the pursuit by the Desert Mounted Corps to encircle the Ottoman infantry fighting in the Judean Hills during the Battle of Nazareth, the Capture of Afulah and Beisan, the Capture of Jenin, the Battle of Samakh and the capture of Tiberias. The EEF destroyed three Ottoman armies during the Battle of Sharon, the Battle of Nablus and the Third Transjordan attack, capturing thousands of prisoners and large quantities of equipment. The EEF pursued the surviving German and Ottoman forces to Damascus and Aleppo, before the Ottoman Empire agreed to the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October 1918, ending the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. The British Mandate of Palestine, and the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon were created to administer the captured territories.[4]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Falls & Becke 1930, pp. 351–372.

- ^ Falls & Becke 1930a, pp. 1–43.

- ^ Falls & Becke 1930a, pp. 44–647.

- ^ Falls & Becke 1930a, pp. 244–647.

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- تاريخ مصر العسكري

- تاريخ فلسطين

- تاريخ عثماني

- حملة سيناء وفلسطين

- الحرب العالمية الأولى

- الاحتلال البريطاني لمصر

- الثورة العربية

- تاريخ عسكري

- Expeditionary units and formations

- Commands of the British Army

- Field armies of the United Kingdom

- Field armies of the United Kingdom in World War I

- Military units and formations of the British Army in World War I

- مصر في الحرب العالمية الأولى

- Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

- World War I orders of battle

- Military units and formations established in 1916

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1919