البلاغة

| يسار زبن ساهم بشكل رئيسي في تحرير هذا المقال

|

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| البلاغة |

|---|

|

البَلاغة هي أحد علوم اللغة العربية، وهو اسم مشتق من فعل بلغ، بمعنى إدراك الغاية أو الوصول إلى النهاية. فــالبلاغة تدل في اللغة على : إيصال معنى الخطاب كاملا إلى المتلقي، سواء أكان سامعا أم قارئا. فالإنسان حينما يمتلك البلاغة يستطيع إيصال المعنى إلى المستمع بإيجاز ويؤثر عليه أيضاً فالبلاغة لها أهمية في إلقاء الخطب والمحاضرات...ووصفها النبي محمد في قوله(ص):«إن من البلاغة لسحراً»))

يقول ابن الأثير:[1]

ويختص بعنصَريْ العاطفة الخيالية معاً -لأن الخيال وليد العاطفة-، وقد سمي علم البيان لأنه يساعدنا على زيادة تبيين المعني وتوضيحه وزيادة التعبير عن العاطفة والوجدان،

علم المعاني

ويختص بعنصر المعاني والأفكار، فهو يرشدنا إلى اختيار التركيب اللغوي المناسب للموقف، كما يرشدنا إلي جعل الصورة اللفظية أقرب ما تكون دلالة على الفكرة التي تخطر في أذهاننا، وهو لا يقتصر على البحث في كل جملة مفردة على حدة، ولكنه يمد نطاق بحثه إلي علاقة كل جملة بالأخرى، وإلي النص كله بوصفه تعبيرا متصلا عن موقف واحد، إذ أرشدنا إلي ما يسمي : الإيجاز والإطناب، والفصل والوصل حسبما يقتضيه مثل الاستعارة والمجاز المرسل والتشبيه والكنايه0

علم البديع

ويختص بعنصر الصياغة، فهو يعمل على حسن تنسيق الكلام حتي يجيء بديعا، من خلال حسن تنظيم الجمل والكلمات، مستخدماً ما يسمي بالمحسنات البديعة - سواء اللفظي منها أو المعنوي-. وإذا نظرنا إلى تاريخ وضع العلوم العربية ,نجد أن معظمها قد وضعت قواعده، وأرسيت أصوله في القرون الأولى من الإسلام ,وألفت العديدة في فن التفسير والنحو والتصريف والفقه وغيرها من فروع المعرفة، وكانت البلاغة من أبطأ الفنون العربية في التدوين والأستقلال كعلم منفرد له قواعده وأصوله لأن المسائل كانت متفرقة بين بطون الكتب، كما كانت مصطلحاتهاغير واضحة بالصور المطلوبة.ولكن ليس معنى هذا انها كانت مجهولة أو مهملة من الباحثين كانت موجودة لكن غير مستقله.

التاريخ

الخطابة اليونانية

مقالة مفصلة: الخطابة اليونانية

مقالة مفصلة: الخطابة اليونانية

كانت الآداب في أثناء هذا الاضطراب كله ينعكس عليها ما انتاب بلاد اليونان من اضمحلال في الأخلاق وضعف في صفات الرجولة. فلم يكن الشعر كما كان من قبل تعبيراً عاطفياً إبداعياً يبتكره الأفراد، بل أصبح تدريباً ظريفاً وثمرة من نتاج العقول في الندوات، وصدى للواجبات والتمارين المدرسية. نعم إن تموثيوس الملطي كتب ملحمة شعرية، ولكنها لم تكن توائم عصر الجدل والنقاش، وظلت بعيدة عن الشعب بُعد موسيقاه في عهدها الباكر؛ وظلت المسرحيات تُمثل ولكن تمثيلها كان أضعف وأضيق نطاقاً من ذي قبل. ذلك إن إقفار خزانة الدولة من المال وضعف الروح الوطنية عند الأثرياء من الأفراد قللا من أقدار الممثلين وأفقداهم ما كان لهم من شأن في ماضي الأيام. واكتفى كُتاب المسرحيات شيئاً فشيئاً بالمقطوعات الموسيقية التي تعزف بين الفصول ولا صلة لها بالمسرحية بدل الأغاني التي تكون جزءاً منها، واختفى اسم رئيس فرقة المرتلين فلم يعد مما يهتم به النظارة، ثم اختفى بعدئذ اسم الشاعر نفسه، ولم يبقَ إلا اسم الممثل. وبَعُدت المسرحية بالتدريج عن القصيدة وأضحت شيئاً فشيئاً عرضاً للحوادث التاريخية، وأصبح العصر كله عصر كبار الممثلين وصغار الكتاب المسرحيين. ذلك أن المأساة اليونانية قد قامت على الدين والأساطير،

وكانت تتطلب شيئاً من التقى والإيمان عند المستمعين، ومن أجل هذا كان لا بد أن يضمحل شأنها حين أوشكت شمس الآلهة على الأفول. وازدهرت المسلاة في الوقت الذي اضمحلت فيه المأساة، وانتقل إليها بعض ما كان يتصف به مسرح يوربديز من براعة، وظرف، ومادة طيبة؛ وفقدت هذه المسلاة الوسطى (400-323) حبها للهجاء السياسي وتشجيعها له، وقت أن كانت السياسة تتطلب "الصديق الصريح"؛ وليس ببعيد أن يكون هذا الهجاء قد حُرِّم أو أن النظارة قد سئموا السياسة بعد أن أصبح حكام أثينة رجالاً من الطراز الثاني. وكان اعتزال الرجل اليوناني بوجه عام الحياة العامة إلى الحياة الخاصة في القرن الرابع سبباً في توجيه اهتمامه إلى شئون منزله وقلبه وإغفاله شئون الدولة. وظهرت في ذلك الوقت المسلاة الأخلاقية، وأخذ الحب يسيطر على مناظرها؛ ولم يكن يسيطر عليها دائماً عن طريق الفضيلة، بل كانت العاهرات يظهرن على خشبة المسرح مع بائعات السمك، والطهاة والفلاسفة الحيارى. وإن كان زواج الممثل والكاتب ينقذ شرفهما في آخر التمثيل. خلت هذه المسرحيات من فحش أرسطوفان ومجونه اللذين كانا سبباً في خشونة المسرحيات وخلوها من الصقل الجميل، ولكنها خلت أيضاً من حيويته وخصب خياله. ولدينا أسماء تسعة وثلاثين شاعراً من كُتاب المسلاة الوسطى، وإن لم يكن لدينا شيء من مسرحياتهم، ولكنا نستطيع أن نحكم من القطع الباقية لدينا أنهم لم يكتبوا شيئاً جديراً بالخلود. وقد كتب ألكسيس الثوريائي (of Thurii) 245 مسرحية، وكتب أنتفانيز Antiphanes 260. لقد ذاع صيتهم في زمانهم فلما انقضى ذلك العهد أفل نجمهم.

أما الخطباء فكان هذا زمانهم. ذلك أن نهضة الصناعة والتجارة قد حولت عقول الناس إلى الحياة الواقعية والعملية؛ وأخذت المدارس التي كانت قبل تعلم أشعار هومر تدرب تلاميذها الآن على أساليب البلاغة. ولقد كان إسيوس Isaeus، وليقورغ، وهيبريديز، ودمديز Demades، وديناركس Deinarchus، وإسكنيز، ودمستين كلهم خطباء سياسيين، يتزعمون أحزاباً سياسية، ويسيطرون ببلاغتهم على عقول الجماهير، وظهر رجال في سراقوصة في الفترات التي ساد فيها الحكم الدمقراطي، أم الدول الدمقراطية فلم تكن تطيقهم؛ وكانت لغة الخطباء الأثينيين تمتاز بالوضوح والقوة، والبعد عن المحسنات اللفظية وكانت تسمو بين الفينة والفينة إلى مراقي الوطنية النبيلة، وتسف إلى المهاترات المنحطة والشتائم القذرة التي لا يُسمح بها حتى في المنازعات الحديثة. وكان ما تتصف به الجمعية الأثينية والمحاكم الشعبية من عدم التجانس في أعضائها سبباً في انحطاط فن الخطابة اليونانية، وحافزاً لها في الوقت عينه. وانتقل هذا الأثر بنوعيه عن طريق الخطابة إلى الأدب اليوناني بوجه عام، فقد كان سرور المواطن الأثيني من سماع الشتائم في خطب الخطباء لا يكاد يقل عن سروره من مشاهدة مباراة لنيل جائزة، وإذا عُرف أن مبارزة لفظية ستقوم بين محاربين بالألفاظ مثل إسكنيز، ودمستين أقبل الناس لسماعهما من القرى النائية والدول الأجنبية؛ وكان أكثر ما يستثيره الخطباء هو غريزة الكبرياء والهوى. وقد عَرَّفَ أفلاطون البلاغة، وكان يكره الخطابة ويصفها بأنها السم القاتل للدمقراطية، عرفها بأنها فن حكم الناس باستثارة مشاعرهم وعواطفهم.

وحتى دمستين نفسه، رغم حيويته وقوة أعصابه، وسموه في كثير من الأحيان إلى فقرات تفيض بالحماسة الوطنية، ورغم هجومه الشديد على الأشخاص هجوماً أخذ يضعف على مر الزمان، ومهارته في تعاقب القصص والجدل في خطبه تعاقباً يريح الأذن ويطرد السآمة، وما في لغته من انسجام وتوازن كان يُعنى بهما كل العناية، ورغم تدفقه في خطبه كالسيل الجارف، نقول إن دمستين نفسه رغم هذا كله يبدو لنا أقل قليلاً من الخطيب العظيم. وكان يرى أن التمثيل هو سر العظمة الخطابية، وبلغ من إيمانه بهذا المبدأ أن كان يعيد خطبه مراراً في كثير من الأناة، ويتلوها على نفسه أمام مرآة. واحتفر لنفسه كهفاً كان يعيش فيه عدة أشهر، لا يكاد يعلم به أحد وكان في هذه الفترات يحلق نصف وجهه ويبقي على النصف الأخر حتى لا تحدثه نفسه بالخروج من مأواه(1). وكان إذا وقف على منصة الخطابة اتجه بوجهه نحو تمثاله، ودار يمنة ويسرة، ووضع يده على جبهته كأنه يفكر، ورفع صوته في أغلب الأحيان إلى حد الصراخ(2). ويقول بلوتارخ إن هذا كله "كان يسر العامة كل السرور، أما المتعلمون أمثال دمتريوس الفاليري (Demetrius of Phalerum) فكانوا يظنون هذا عملاً حقيراً، مهيناً، لا يتفق مع الرجولة الحقة". وإنا لَنُسَرّ من حركات دمستين المسرحية، ونعجب بتقديره لنفسه واعتزازه بها، وتحيرنا استطراداته وتُرَوّعنا بذائته. وليس في خطبه إلا القليل من الفكاهة والقليل من الفلسفة. ولولا حماسته الوطنية، وما يبدو من إخلاص في دعوته الحارة اليائسة إلى الحرية، لما كان له شأن كبير.

وبلغت الخطابة اليونانية أرقى درجاتها في عام 330. وكان تسفون Ctesiphon قبل ذلك العام بست سنين قد اقترح على المجلس مبدئياً أن يهدي دمستين تاجاً أو إكليلاً من الزهر اعترافاً منه بحسن سياسته، وبما قدمه للدولة من منح مالية كثيرة. ووافق المجلس على هذا الاقتراح وأراد إسكنيز أن يحول بين منافسه وبين هذا الشرف العظيم فاتهم تسفون بأنه عرض على المجلس اقتراحاً غير دستوري (وهو اتهام صحيح من الناحية الشكلية) وأجلت القضية المرة بعد المرة، ثم عُرضت أخيراً على هيئة القضاء المؤلفة من خمسمائة من المواطنين. وكانت هذه بطبيعة الحال قضية من أشهر القضايا شهدها كل من استطاع الحضور إلى أثينة مهما بعد موطنه؛ ذلك بأن أعظم خطباء أثينة في ذلك الوقت كان في واقع الأمر يدافع فيها عن سمعته وعن حياته السياسية. ولم يُضِع إسكنيز في مهاجمة تسفوت إلا قليلاً من الوقت ولكنه وجه هجومه إلى أخلاق دمستين وسيرته، ورد عليه دمستين بخطبة من نوع خطبته هي خطبته الشهيرة المعروفة باسم "في سبيل التاج". ولا نزال نحس في كل سطر من أسطر الخطبتين بما كان يضطرم في صدر صاحبيهما من اهتياج شديد، وحقد في قلب عدوين التقيا وجهاً لوجه في ميدان القتال. وكان دمستين يعرف أن الهجوم أفضل من الدفاع، فقال إن فليب قد اختار بوقاً له في أثينة أحط خطبائها وأشدهم فساداً، ثم أخذ يرسم صورة لحياة إسكنيز يتجلى فيها الحقد بأوضح معانيه فقال:

لابد لي أن أدلكم على حقيقة هذا الرجل الذي يطلق لسانه بالشتائم المقذعة...وإلى أي الآباء ينتسب. الفضيلة أيها الوغد الخائن!...ما شأنك أنت أو أسرتك بالفضيلة؟...وبأي حق تتحدث عن التربية والتعليم؟...هل أقص على الناس كيف كان أبوك عبداً يدير مدرسة أولية قرب هيكل ثسيوس. وكيف كان مصفداً بالحديد في ساقه، وكيف كان حول عنقه طوق من الخشب، وكيف كانت أمك تقيم حفلات الزواج في مرافق بيت في وضح النهار؟...لقد كانت تساعد أباك في كدحه في مدرسة صغيرة، تطحن له الخبز، وتنظف المقاعد بالأسفنج، وتكنس الحجرة، وتقوم بعمل الخادم...ثم سجلت اسمك في سجل أبرشيتك - وليس في مقدور أحد أن يعرف كيف استطعت أن تفعل ذلك، ولكن ما علينا من هذا - لقد اخترت لنفسك مهنة خليقة بأشرف الرجال المهذبين فكنت كاتباً وموصل رسائل لصغار الموظفين. وبعد أن ارتكبت جميع الجرائم التي تعير بها غيرك من الناس، أعفيت من هذا العمل...والتحقت بخدمة الممثلَين الشهيرَين سميلس Simylus وسقراط المشهورين باسم "المدمدمين". ومثلت أدواراً صغيرة تحت إشرافهم، فكنت تلتقط التين والعنب والزيتون وتعيش على هذه القذائف خيراً مما تعيش من جميع الوقائع التي كنت تخوضها للنجاة من الموت. إن الحرب التي كانت قائمة بينك وبين النظارة لم تكن فيها هدنة أو وقف للقتال...

وازن إذن يا إسكنيز بين حياتك وحياتي. لقد كنت تعلم مبادئ القراءة وكنت أنا طالباً في المدرسة؛ وكنت أنت راقصاً وكنت أنا رئيس الممثلين...وكنت كاتباً عمومياً، وكنت أنا خطيباً عاماً. وكنت ممثلاً من الدرجة الثالثة وكنت أنا ممن يشهدون التمثيل. وأخفقت أنت في تمثيل دورك وسخرت أنا منك بالصفير(3).

وكانت هذه خطبة عنيفة؛ ولم تكن أنموذجاً للترتيب والأدب ولكنها كانت فصيحة اللفظ شديدة الانفعال إلى حد حملت القضاة على أن يبرئوا تسفون بأغلبية خمسة أصوات ضد صوت واحد. وفي العام التالي منحت الجمعية دمستين التاج المتنازع. ولما عجز إسكنيز عن أداء الغرامة التي تُفرض حتماً على مَن يعجز عن إثبات جريمة يتهم بها أحد المواطنين، فر إلى رودس، حيث أخذ يكسب الكفاف من العيش بتعليم البلاغة. وتقول إحدى الروايات إن دمستين كان يرسل إليه المال ليخفف عنه آلام الفاقة.

الهند

India's Struggle for Independence offers a vivid description of the culture that sprang up around the newspaper in village India of the early 1870s:

A newspaper would reach remote villages and would then be read by a reader to tens of others. Gradually library movements sprung up all over the country. A local 'library' would be organized around a single newspaper. A table, a bench or two or a charpoy would constitute the capital equipment. Every piece of news or editorial comment would be read or heard and thoroughly discussed. The newspaper not only became the political educator; reading or discussing it became a form of political participation.[2]

This reading and discussion was the focal point of origin of the modern Indian rhetorical movement. Much before this, ancients such as Kautilya, Birbal, and the like indulged in a great deal of discussion and persuasion.

Keith Lloyd argued that much of the recital of the Vedas can be likened to the recital of ancient Greek poetry.[3] Lloyd proposed including the Nyāya Sūtras in the field of rhetorical studies, exploring its methods within their historical context, comparing its approach to the traditional logical syllogism, and relating it to modern perspectives of Stephen Toulmin, Kenneth Burke, and Chaim Perelman.

Nyaya is a Sanskrit word which means "just" or "right" and refers to "the science of right and wrong reasoning".[4] Sutra is also a Sanskrit word which means string or thread. Here sutra refers to a collection of aphorism in the form of a manual. Each sutra is a short rule usually consisted of one or two sentences. An example of a sutra is: "Reality is truth, and what is true is so, irrespective of whether we know it is, or are aware of that truth." The Nyāya Sūtras is an ancient Indian Sanskrit text composed by Aksapada Gautama. It is the foundational text of the Nyaya school of Hindu philosophy. It is estimated that the text was composed between 6th-century ق.م. and 2nd-century م. The text may have been composed by more one author, over a period of time.[5] Radhakrishan and Moore placed its origin in the third century ق.م. "though some of the contents of the Nyaya Sutra are certainly a post-Christian era".[4]:36 The ancient school of Nyaya extended over a period of one thousand years, beginning with Gautama about 550 ق.م. and ending with Vatsyayana about 400 م.[6]

Nyaya provides insight into Indian rhetoric. Nyaya presents an argumentative approach with which a rhetor can decide about any argument. In addition, it proposes an approach to thinking about cultural tradition which is different from Western rhetoric. Whereas Toulmin emphasizes the situational dimension of argumentative genre as the fundamental component of any rhetorical logic; Nyaya views this situational rhetoric[vague].

Some of India's famous rhetors include Kabir Das, Rahim Das, Chanakya, and Chandragupt Maurya.

روما

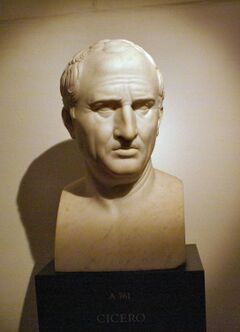

شيشرون

For the Romans, oration became an important part of public life. Cicero (106–43 ق.م.) was chief among Roman rhetoricians and remains the best known ancient orator and the only orator who both spoke in public and produced treatises on the subject. Rhetorica ad Herennium, formerly attributed to Cicero but now considered to be of unknown authorship, is one of the most significant works on rhetoric and is still widely used as a reference today. It is an extensive reference on the use of rhetoric, and in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, it achieved wide publication as an advanced school text on rhetoric.

Cicero charted a middle path between the competing Attic and Asiatic styles to become considered second only to Demosthenes among history's orators.[7] His works include the early and very influential De Inventione (On Invention, often read alongside Ad Herennium as the two basic texts of rhetorical theory throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance), De Oratore (a fuller statement of rhetorical principles in dialogue form), Topics (a rhetorical treatment of common topics, highly influential through the Renaissance), Brutus (a discussion of famous orators), and Orator (a defense of Cicero's style). Cicero also left a large body of speeches and letters which would establish the outlines of Latin eloquence and style for generations.

The rediscovery of Cicero's speeches (such as the defense of Archias) and letters (to Atticus) by Italians like Petrarch helped to ignite the Renaissance.[citation needed]

Cicero championed the learning of Greek (and Greek rhetoric), contributed to Roman ethics, linguistics, philosophy, and politics, and emphasized the importance of all forms of appeal (emotion, humor, stylistic range, irony, and digression in addition to pure reasoning) in oratory. But perhaps his most significant contribution to subsequent rhetoric, and education in general, was his argument that orators learn not only about the specifics of their case (the hypothesis) but also about the general questions from which they derived (the theses).[citation needed] Thus, in giving a speech in defense of a poet whose Roman citizenship had been questioned, the orator should examine not only the specifics of that poet's civic status, he should also examine the role and value of poetry and of literature more generally in Roman culture and political life. The orator, said Cicero, needed to be knowledgeable about all areas of human life and culture, including law, politics, history, literature, ethics, warfare, medicine, and even arithmetic and geometry. Cicero gave rise to the idea that the "ideal orator" be well-versed in all branches of learning: an idea that was rendered as "liberal humanism", and that lives on today in liberal arts or general education requirements in colleges and universities around the world.[8]

كوينتليان

Quintilian (35–100 م) began his career as a pleader in the courts of law; his reputation grew so great that Vespasian created a chair of rhetoric for him in Rome. The culmination of his life's work was the Institutio Oratoria (Institutes of Oratory, or alternatively, The Orator's Education), a lengthy treatise on the training of the orator, in which he discusses the training of the "perfect" orator from birth to old age and, in the process, reviews the doctrines and opinions of many influential rhetoricians who preceded him.

In the Institutes, Quintilian organizes rhetorical study through the stages of education that an aspiring orator would undergo, beginning with the selection of a nurse. Aspects of elementary education (training in reading and writing, grammar, and literary criticism) are followed by preliminary rhetorical exercises in composition (the progymnasmata) that include maxims and fables, narratives and comparisons, and finally full legal or political speeches. The delivery of speeches within the context of education or for entertainment purposes became widespread and popular under the term "declamation".

This work was available only in fragments in medieval times, but the discovery of a complete copy at the Abbey of St. Gall in 1416 led to its emergence as one of the most influential works on rhetoric during the Renaissance.

Quintilian's work describes not just the art of rhetoric, but the formation of the perfect orator as a politically active, virtuous, publicly minded citizen. His emphasis was on the ethical application of rhetorical training, in part in reaction against the tendency in Roman schools toward standardization of themes and techniques. At the same time that rhetoric was becoming divorced from political decision making, rhetoric rose as a culturally vibrant and important mode of entertainment and cultural criticism in a movement known as the "Second Sophistic", a development that gave rise to the charge (made by Quintilian and others) that teachers were emphasizing style over substance in rhetoric.

القرون الوسطى إلى التنوير

After the breakup of the western Roman Empire, the study of rhetoric continued to be central to the study of the verbal arts. However the study of the verbal arts went into decline for several centuries, followed eventually by a gradual rise in formal education, culminating in the rise of medieval universities. Rhetoric transmuted during this period into the arts of letter writing (ars dictaminis) and sermon writing (ars praedicandi). As part of the trivium, rhetoric was secondary to the study of logic, and its study was highly scholastic: students were given repetitive exercises in the creation of discourses on historical subjects (suasoriae) or on classic legal questions (controversiae).

Although he is not commonly regarded as a rhetorician, St. Augustine (354–430) was trained in rhetoric and was at one time a professor of Latin rhetoric in Milan. After his conversion to Christianity, he became interested in using these "pagan" arts for spreading his religion. He explores this new use of rhetoric in De doctrina Christiana, which laid the foundation of what would become homiletics, the rhetoric of the sermon. Augustine asks why "the power of eloquence, which is so efficacious in pleading either for the erroneous cause or the right", should not be used for righteous purposes.[9]

One early concern of the medieval Christian church was its attitude to classical rhetoric itself. Jerome (d. 420) complained, "What has Horace to do with the Psalms, Virgil with the Gospels, Cicero with the Apostles?"[10] Augustine is also remembered for arguing for the preservation of pagan works and fostering a church tradition that led to conservation of numerous pre-Christian rhetorical writings.

Rhetoric would not regain its classical heights until the Renaissance, but new writings did advance rhetorical thought. Boethius (ح. 480–524), in his brief Overview of the Structure of Rhetoric, continues Aristotle's taxonomy by placing rhetoric in subordination to philosophical argument or dialectic.[11] The introduction of Arab scholarship from European relations with the Muslim empire (in particular Al-Andalus) renewed interest in Aristotle and Classical thought in general, leading to what some historians call the 12th century Renaissance. A number of medieval grammars and studies of poetry and rhetoric appeared.

Late medieval rhetorical writings include those of St. Thomas Aquinas (ح. 1225–1274), Matthew of Vendôme (Ars Versificatoria, ح. 1175), and Geoffrey of Vinsauf (Poetria Nova, 1200–1216). Pre-modern female rhetoricians, outside of Socrates' friend Aspasia, are rare; but medieval rhetoric produced by women either in religious orders, such as Julian of Norwich (d. 1415), or the very well-connected Christine de Pizan (ح. 1364–ح. 1430), did occur although it was not always recorded in writing.

In his 1943 Cambridge University doctoral dissertation in English, Canadian Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980) surveys the verbal arts from approximately the time of Cicero down to the time of Thomas Nashe (1567–ح. 1600).[12] His dissertation is still noteworthy for undertaking to study the history of the verbal arts together as the trivium, even though the developments that he surveys have been studied in greater detail since he undertook his study. As noted below, McLuhan became one of the most widely publicized communication theorists of the 20th century.

Another interesting record of medieval rhetorical thought can be seen in the many animal debate poems popular in England and the continent during the Middle Ages, such as The Owl and the Nightingale (13th century) and Geoffrey Chaucer's Parliament of Fowls.

القرن السادس عشر

Renaissance humanism defined itself broadly as disfavoring medieval scholastic logic and dialectic and as favoring instead the study of classical Latin style and grammar and philology and rhetoric.[13]

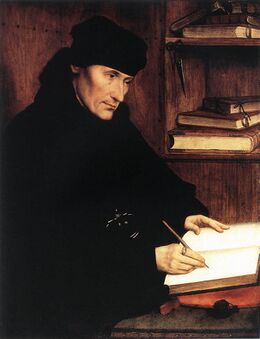

One influential figure in the rebirth of interest in classical rhetoric was Erasmus (ح. 1466–1536). His 1512 work, De Duplici Copia Verborum et Rerum (also known as Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style), was widely published (it went through more than 150 editions throughout Europe) and became one of the basic school texts on the subject. Its treatment of rhetoric is less comprehensive than the classic works of antiquity, but provides a traditional treatment of res-verba (matter and form). Its first book treats the subject of elocutio, showing the student how to use schemes and tropes; the second book covers inventio. Much of the emphasis is on abundance of variation (copia means "plenty" or "abundance", as in copious or cornucopia), so both books focus on ways to introduce the maximum amount of variety into discourse. For instance, in one section of the De Copia, Erasmus presents two hundred variations of the sentence "Always, as long as I live, I shall remember you" ("Semper, dum vivam, tui meminero.") Another of his works, the extremely popular The Praise of Folly, also had considerable influence on the teaching of rhetoric in the later 16th century. Its orations in favour of qualities such as madness spawned a type of exercise popular in Elizabethan grammar schools, later called adoxography, which required pupils to compose passages in praise of useless things.

Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540) also helped shape the study of rhetoric in England. A Spaniard, he was appointed in 1523 to the Lectureship of Rhetoric at Oxford by Cardinal Wolsey, and was entrusted by Henry VIII to be one of the tutors of Mary. Vives fell into disfavor when Henry VIII divorced Catherine of Aragon and left England in 1528. His best-known work was a book on education, De Disciplinis, published in 1531, and his writings on rhetoric included Rhetoricae, sive De Ratione Dicendi, Libri Tres (1533), De Consultatione (1533), and a treatise on letter writing, De Conscribendis Epistolas (1536).

It is likely that many well-known English writers were exposed to the works of Erasmus and Vives (as well as those of the Classical rhetoricians) in their schooling, which was conducted in Latin (not English), often included some study of Greek, and placed considerable emphasis on rhetoric.[14]

The mid-16th century saw the rise of vernacular rhetorics—those written in English rather than in the Classical languages. Adoption of works in English was slow, however, due to the strong scholastic orientation toward Latin and Greek. Leonard Cox's The Art or Crafte of Rhetoryke (ح. 1524–1530; second edition published in 1532) is the earliest text on rhetorics in English; it was, for the most part, a translation of the work of Philipp Melanchthon.[15] Thomas Wilson's The Arte of Rhetorique (1553) presents a traditional treatment of rhetoric, for instance, the standard five canons of rhetoric. Other notable works included Angel Day's The English Secretorie (1586, 1592), George Puttenham's The Arte of English Poesie (1589), and Richard Rainholde's Foundacion of Rhetorike (1563).

During this same period, a movement began that would change the organization of the school curriculum in Protestant and especially Puritan circles and that led to rhetoric losing its central place. A French scholar, Petrus Ramus (1515–1572), dissatisfied with what he saw as the overly broad and redundant organization of the trivium, proposed a new curriculum. In his scheme of things, the five components of rhetoric no longer lived under the common heading of rhetoric. Instead, invention and disposition were determined to fall exclusively under the heading of dialectic, while style, delivery, and memory were all that remained for rhetoric.[16] Ramus was martyred during the French Wars of Religion. His teachings, seen as inimical to Catholicism, were short-lived in France but found a fertile ground in the Netherlands, Germany, and England.[17]

One of Ramus' French followers, Audomarus Talaeus (Omer Talon) published his rhetoric, Institutiones Oratoriae, in 1544. This work emphasized style, and became so popular that it was mentioned in John Brinsley's (1612) Ludus literarius; or The Grammar Schoole as being the "most used in the best schooles". Many other Ramist rhetorics followed in the next half-century, and by the 17th century, their approach became the primary method of teaching rhetoric in Protestant and especially Puritan circles.[18] John Milton (1608–1674) wrote a textbook in logic or dialectic in Latin based on Ramus' work.[19]

Ramism could not exert any influence on the established Catholic schools and universities, which remained loyal to Scholasticism, or on the new Catholic schools and universities founded by members of the Society of Jesus or the Oratorians, as can be seen in the Jesuit curriculum (in use up to the 19th century across the Christian world) known as the Ratio Studiorum.[20] If the influence of Cicero and Quintilian permeates the Ratio Studiorum, it is through the lenses of devotion and the militancy of the Counter-Reformation. The Ratio was indeed imbued with a sense of the divine, of the incarnate logos, that is of rhetoric as an eloquent and humane means to reach further devotion and further action in the Christian city, which was absent from Ramist formalism. The Ratio is, in rhetoric, the answer to Ignatius Loyola's practice, in devotion, of "spiritual exercises". This complex oratorical-prayer system is absent from Ramism.

القرن السابع عشر

In New England and at Harvard College (founded 1636), Ramus and his followers dominated.[21][صفحة مطلوبة] However, in England, several writers influenced the course of rhetoric during the 17th century, many of them carrying forward the dichotomy[حدد] that had been set forth by Ramus and his followers during the preceding decades. This century also saw the development of a modern, vernacular style that looked to English, rather than to Greek, Latin, or French models.

Francis Bacon (1561–1626), although not a rhetorician, contributed to the field in his writings. One of the concerns of the age was to find a suitable style for the discussion of scientific topics, which needed above all a clear exposition of facts and arguments, rather than an ornate style. Bacon in his The Advancement of Learning criticized those who are preoccupied with style rather than "the weight of matter, worth of subject, soundness of argument, life of invention, or depth of judgment".[22] On matters of style, he proposed that the style conform to the subject matter and to the audience, that simple words be employed whenever possible, and that the style should be agreeable.[23][صفحة مطلوبة]

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) also wrote on rhetoric. Along with a shortened translation of Aristotle's Rhetoric, Hobbes also produced a number of other works on the subject. Sharply contrarian on many subjects, Hobbes, like Bacon, also promoted a simpler and more natural style that used figures of speech sparingly.

Perhaps the most influential development in English style came out of the work of the Royal Society (founded in 1660), which in 1664 set up a committee to improve the English language. Among the committee's members were John Evelyn (1620–1706), Thomas Sprat (1635–1713), and John Dryden (1631–1700). Sprat regarded "fine speaking" as a disease, and thought that a proper style should "reject all amplifications, digressions, and swellings of style" and instead "return back to a primitive purity and shortness".[24]

While the work of this committee never went beyond planning, John Dryden is often credited with creating and exemplifying a new and modern English style. His central tenet was that the style should be proper "to the occasion, the subject, and the persons".[25] As such, he advocated the use of English words whenever possible instead of foreign ones, as well as vernacular, rather than Latinate, syntax. His own prose (and his poetry) became exemplars of this new style.

القرن الثامن عشر

Arguably one of the most influential schools of rhetoric during the 18th century was Scottish Belletristic rhetoric, exemplified by such professors of rhetoric as Hugh Blair whose Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres saw international success in various editions and translations, and Lord Kames with his influential Elements of Criticism.

Another notable figure in 18th century rhetoric was Maria Edgeworth, a novelist and children's author whose work often parodied the male-centric rhetorical strategies of her time. In her 1795 "An Essay on the Noble Science of Self-Justification," Edgeworth presents a satire of Enlightenment rhetoric's science-centrism and the Belletristic Movement.[26] She was called "the great Maria" by Sir Walter Scott, with whom she corresponded,[27] and by modern scholars is noted as "a transgressive and ironic reader" of the 18th century rhetorical norms.[28]

البلاغة الحديثة

At the turn of the 20th century, there was a revival of rhetorical study manifested in the establishment of departments of rhetoric and speech at academic institutions, as well as the formation of national and international professional organizations.[29] The early interest in rhetorical studies was a movement away from elocution as taught in English departments in the United States, and an attempt to refocus rhetorical studies from delivery-only to civic engagement and a "rich complexity" of the nature of rhetoric.[30]

By the 1930s, advances in mass media technology led to a revival of the study of rhetoric, language, persuasion, and political rhetoric and its consequences. The linguistic turn in philosophy also contributed to this revival. The term rhetoric came to be applied to media forms other than verbal language, e.g. visual rhetoric, "temporal rhetorics",[31] and the "temporal turn"[32] in rhetorical theory and practice.

The rise of advertising and of mass media such as photography, telegraphy, radio, and film brought rhetoric more prominently into people's lives. The discipline of rhetoric has been used to study how advertising persuades,[33] and to help understand the spread of fake news and conspiracy theories on social media.[34]

Notable theorists

- Chaïm Perelman

- Perelman was among the most important argumentation theorists of the 20th century. His chief work is the Traité de l'argumentation—la nouvelle rhétorique (1958), with Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, which was translated into English as The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation.[35] Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca move rhetoric from the periphery to the center of argumentation theory. Among their most influential concepts are "dissociation", "the universal audience", "quasi-logical argument", and "presence".

- Kenneth Burke

- Burke was a rhetorical theorist, philosopher, and poet. Many of his works are central to modern rhetorical theory: Counterstatement (1931), A Grammar of Motives (1945), A Rhetoric of Motives (1950), and Language as Symbolic Action (1966). Among his influential concepts are "identification", "consubstantiality", and the "dramatistic pentad". He described rhetoric as "the use of language as a symbolic means of inducing cooperation in beings that by nature respond to symbols".[36] In relation to Aristotle's theory, Aristotle was more interested in constructing rhetoric, while Burke was interested in "debunking" it.

- Edwin Black

- Black was a rhetorical critic best known for his book Rhetorical Criticism: A Study in Method[37] (1965) in which he criticized the dominant "neo-Aristotelian" tradition in American rhetorical criticism as having little in common with Aristotle "besides some recurrent topics of discussion and a vaguely derivative view of rhetorical discourse". Furthermore, he contended, because rhetorical scholars had been focusing primarily on Aristotelian logical forms they often overlooked important, alternative types of discourse. He also published several highly influential essays including: "Secrecy and Disclosure as Rhetorical Forms",[38] "The Second Persona",[39] and "A Note on Theory and Practice in Rhetorical Criticism".[40]

- Marshall McLuhan

- McLuhan was a media theorist whose theories and whose choice of objects of study are important to the study of rhetoric. McLuhan's book The Mechanical Bride[41] was a compilation of exhibits of ads and other materials from popular culture with short essays involving rhetorical analyses of the persuasive strategies in each item. McLuhan later shifted the focus of his rhetorical analysis and began to consider how communication media themselves affect us as persuasive devices. His famous dictum "the medium is the message" highlights the significance of the medium itself. This shift in focus led to his two most widely known books, The Gutenberg Galaxy[42] and Understanding Media.[43] These books represent an inward turn to attending to one's consciousness in contrast to the more outward orientation of other rhetoricians toward sociological considerations and symbolic interaction. No other scholar of the history and theory of rhetoric was as widely publicized in the 20th century as McLuhan.

- I. A. Richards

- Richards was a literary critic and rhetorician. His The Philosophy of Rhetoric is an important text in modern rhetorical theory.[44] In this work, he defined rhetoric as "a study of misunderstandings and its remedies", and introduced the influential concepts tenor and vehicle to describe the components of a metaphor—the main idea and the concept to which it is compared.[44]

- The Groupe µ

- This interdisciplinary team contributed to the renovation of the elocutio in the context of poetics and modern linguistics, significantly with Rhétorique générale[45] and Rhétorique de la poésie (1977).

- Stephen Toulmin

- Toulmin was a philosopher whose Uses of Argument is an important text in modern rhetorical theory and argumentation theory.[46]

- Richard Vatz

- Vatz is responsible for the salience-agenda/meaning-spin conceptualization of rhetoric, later revised to an "agenda-spin" model, a conceptualization which emphasizes the persuader's responsibility for the agenda and spin he/she creates. His theory is notable for its agent-focused perspective, articulated in The Only Authentic Book of Persuasion.[47]

- Richard M. Weaver

- Weaver was a rhetorical and cultural critic known for his contributions to the new conservatism. He focused on the ethical implications of rhetoric in his books Language is Sermonic and The Ethics of Rhetoric. According to Weaver there are four types of argument, and through the argument type a rhetorician habitually uses a critic can discern their worldview. Those who prefer the argument from genus or definition are idealists. Those who argue from similitude, such as poets and religious people, see the connectedness between things. The argument from consequence sees a cause and effect relationship. Finally the argument from circumstance considers the particulars of a situation and is an argument preferred by liberals.

- Gloria Anzaldúa

- Anzaldúa was a "Mestiza" and "Borderland" rhetorician, as well as a Mexican-American poet and pioneer in the field of Chicana lesbian feminism. Mestiza and Borderland rhetoric focuses on one's formation of identity, disregarding societal and discourse labels.[48] With "Mestiza" rhetoric, one views the world as discovering one's "self" in others and others' "self" in you. Through this process, one accepts living in a world of contradictions and ambiguity.[48] Anzaldua learned to balance cultures, being Mexican in the eyes of the Anglo-majority and Indian in a Mexican culture.[48] Her other notable works include: Sinister Wisdom,[49] Borderlands/La Fronters: The New Mestiza,[49] and La Prieta.[50]

- Gertrude Buck

- Buck was one of the prominent female rhetorical theorists who was also a composition educator. Her scholastic contributions such as "The present status of Rhetorical Theory"[51] mean to inspire the egalitarian status[مطلوب توضيح] of hearers-speakers to achieve the goal of communication. Another piece that she edited with Newton Scott is A Brief English Grammar which troubled[مطلوب توضيح] the common prescriptive grammar. This book received a lot of praise and critiques for descriptive nature of social responsibility from non-mainstream beliefs.قالب:Incomprehensible inline[52]

- Krista Ratcliffe

- Ratcliffe is a feminist and critical race rhetorical theorist. In her book, Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness, Ratcliffe puts forward a theory and model of rhetorical listening as "a trope for interpretive invention and more particularly as a code of cross-cultural conduct."[53] This book has been described as "taking the field of feminist rhetoric to a new place"[54] in its movement away from argumentative rhetoric and towards an undivided logos wherein speaking and listening are reintegrated. Reviewers have also acknowledged the theoretical contributions Ratcliffe makes towards a model for appreciating and acknowledging difference in instances of cross-cultural communication.[55]

- Sonja K. Foss

- Foss is a rhetorical scholar and educator in the discipline of communication. Her research and teaching interests are in contemporary rhetorical theory and criticism, feminist perspectives on communication, the incorporation of marginalized voices into rhetorical theory and practice, and visual rhetoric.[importance?]

وسائل التحليل

Criticism seen as a method

Rhetoric can be analyzed by a variety of methods and theories. One such method is criticism. When those using criticism analyze instances of rhetoric what they do is called rhetorical criticism

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from September 2023

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- CS1 maint: postscript

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of سبتمبر 2023

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All Wikipedia articles needing clarification

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from September 2023

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2023

- Articles containing Early Modern English-language text

- Articles needing more detailed references

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from September 2023

- All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from September 2023

- سرديات

- تفكير نقدي

- علوم عربية

- بلاغة

- Applied linguistics

- Communication studies

- Critical thinking skills

- History of logic

- Intellectual history

- Narratology

- Philosophical logic

- Philosophy of logic

- Philosophy of language