تاريخ ليبيا في عهد معمر القذافي

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| تاريخ ليبيا |

|---|

|

| قبل التاريخ |

| التاريخ القديم (قبل 146 ق.م) |

| الحكم الروماني (146 ق.م– 640 م) |

| الحكم العربي (640–1551) |

| الحكم العثماني (1551–1911) |

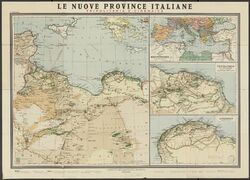

| الاستعمار الإيطالي (1911–1934) |

| ليبيا الإيطالية (1934–1943) |

| احتلال الحلفاء (1943–1951) |

| مملكة ليبيا (1951–1969) |

| حكم القذافي (1969–2011) |

| الثورة الليبية (2011) |

| المجلس الانتقالي (2011–الآن) |

|

|

Muammar Gaddafi became the de facto leader of Libya on 1 September 1969 after leading a group of young Libyan military officers against King Idris I in a bloodless coup d'état. After the king had fled the country, the Libyan Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) headed by Gaddafi abolished the monarchy and the old constitution and established the Libyan Arab Republic, with the motto "freedom, socialism and unity".[1]

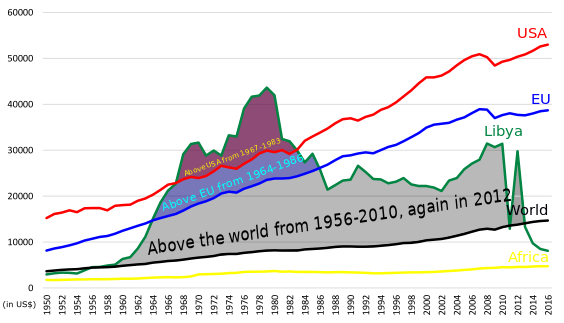

After coming to power, the RCC government initiated a process of directing funds toward providing education, health care and housing for all. Public education in the country became free and primary education compulsory for both sexes. Medical care became available to the public at no cost, but providing housing for all was a task the RCC government was not able to complete.[2] Under Gaddafi, per capita income in the country rose to more than US $11,000, the fifth highest in Africa.[3] The increase in prosperity was accompanied by a controversial foreign policy, and there was increased domestic political repression.[1][4]

During the 1980s and 1990s, Gaddafi, in alliance with the Eastern Bloc and Fidel Castro's Cuba, openly supported rebel movements like Nelson Mandela's African National Congress, the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Irish Republican Army and the Polisario Front (Western Sahara). Gaddafi's government was either known to be or suspected of participating in or aiding terrorist acts by these and other proxy forces. Additionally, Gaddafi undertook several invasions of neighboring states in Africa, notably Chad in the 1970s and 1980s. All of his actions led to a deterioration of Libya's foreign relations with several countries, mostly Western states,[5] and culminated in the 1986 United States bombing of Libya. Gaddafi defended his government's actions by citing the need to support anti-imperialist and anti-colonial movements around the world. Notably, Gaddafi supported anti-Zionist, pan-Africanist and black civil rights movements. Gaddafi's behavior, often erratic, led some outsiders to conclude that he was not mentally sound, a claim disputed by the Libyan authorities and other observers close to Gaddafi. Despite receiving extensive aid and technical assistance from the Soviet Union and its allies, Gaddafi retained close ties to pro-American governments in Western Europe, largely by incentivising Western oil companies with promises of access to lucrative Libyan energy sectors. After the 9/11 attacks, strained relations between Libya and the West were mostly normalised, and sanctions against the country relaxed, in exchange for Libyan efforts to shrink its nuclear program.

In early 2011, a civil war broke out in the context of the wider "Arab Spring". The rebel anti-Gaddafi forces formed a committee named the National Transitional Council on 27 February 2011. It was meant to act as an interim authority in the rebel-controlled areas. After killings by government forces[6] in addition to those by the rebel forces,[7] a multinational coalition led by NATO forces intervened on 21 March 2011 in support of the rebels.[8][9][10] The International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant against Gaddafi and his entourage on 27 June 2011. Gaddafi's government was overthrown in the wake of the fall of Tripoli to the rebel forces on 20 August 2011, although pockets of resistance held by forces in support of Gaddafi's government held out for another two months, especially in Gaddafi's hometown of Sirte, which he declared the new capital of Libya on 1 September 2011.[11] The fall of the last remaining cities under pro-Gaddafi control and Sirte's capture on 20 October 2011, followed by the subsequent killing of Gaddafi, marked the end of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.

The name of Libya was changed several times during Gaddafi's tenure as the leader. At first, the name was the Libyan Arab Republic. In 1977, the name was changed to Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.[12] Jamahiriya was a term coined by Gaddafi,[12] usually translated as "state of the masses". The country was renamed again in 1986 as the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, after the 1986 United States bombing of Libya.

Coup d'état of 1969

Libyan Arab Republic (1969–1977)

Libyan Arab Republic الجمهورية العربية الليبية Al-Jumhūrīyah Al-ʿArabiyyah Al-Lībiyyah (بالعربية) Repubblica Araba Libica (Italian) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969–1977 | |||||||||

النشيد: الله أكبر Allahu Akbar God is the Greatest | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| العاصمة | Tripoli | ||||||||

| اللغات الشائعة | Arabic Italian | ||||||||

| الحكومة | One-party state under a military dictatorship | ||||||||

| Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council | |||||||||

• 1969–1977 | Muammar Gaddafi | ||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Cold War | ||||||||

| 1 September 1969 | |||||||||

• Jamahiriya established | 2 March 1977 | ||||||||

| التعداد | |||||||||

• 1977 | 2,681,900 | ||||||||

| Currency | Libyan dinar | ||||||||

| Calling code | 218 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Attempted counter-coups

Following the formation of the Libyan Arab Republic, Gaddafi and his associates insisted that their government would not rest on individual leadership, but rather on collegial decision making.

Transition to the Jamahiriya (1973–1977)

Libyan-Egyptian War

Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–2011)

Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الإشتراكية العظمى al-Jamāhīrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha'bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah al-'Uẓmá | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977–2011 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| العاصمة | Tripoli (1977–2011) Sirte (2011)[13] | ||||||||

| اللغات الشائعة | Arabic | ||||||||

| الدين | Islam | ||||||||

| الحكومة | Unitary Islamic socialist Jamahiriya | ||||||||

| Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution | |||||||||

• 1977–2011 | Muammar Gaddafi | ||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Cold War • War on Terror | ||||||||

• People's Authority | 2 March 1977 | ||||||||

| 28 August 2011 | |||||||||

| 20 October 2011 | |||||||||

| التعداد | |||||||||

• 2010 | 6,355,100 | ||||||||

| Currency | Libyan dinar | ||||||||

| Calling code | 218 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

On 2 March 1977, the General People's Congress (GPC), at Gaddafi's behest, adopted the "Declaration of the Establishment of the People's Authority"[14][15] and proclaimed the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (العربية: الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية[16] al-Jamāhīrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha'bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah). In the official political philosophy of Gaddafi's state, the "Jamahiriya" system was unique to the country, although it was presented as the materialization of the Third International Theory, proposed by Gaddafi to be applied to the entire Third World. The GPC also created the General Secretariat of the GPC, comprising the remaining members of the defunct Revolutionary Command Council, with Gaddafi as general secretary, and also appointed the General People's Committee, which replaced the Council of Ministers, its members now called secretaries rather than ministers.

The Libyan government claimed that the Jamahiriya was a direct democracy without any political parties, governed by its populace through local popular councils and communes (named Basic People's Congresses). Official rhetoric disdained the idea of a nation state, tribal bonds remaining primary, even within the ranks of the Armed Forces of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.[17]

Etymology

Reforms (1977–1980)

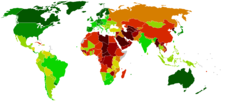

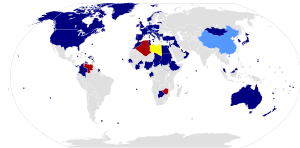

| Full democracies: 9–10 8–8.9 Flawed democracies: 7–7.9 6–6.9 No data | Hybrid regimes: 5–5.9 4–4.9 Authoritarian regimes: 3–3.9 2–2.9 0–1.9 |

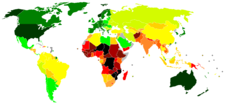

| 0.900 and over 0.850–0.899 0.800–0.849 0.750–0.799 0.700–0.749 | 0.650–0.699 0.600–0.649 0.550–0.599 0.500–0.549 0.450–0.499 | 0.400–0.449 0.350–0.399 0.300–0.349 under 0.300 Data unavailable |

Gaddafi as permanent "Leader of the Revolution"

The changes in Libyan leadership since 1976 culminated in March 1979, when the General People's Congress declared that the "vesting of power in the masses" and the "separation of the state from the revolution" were complete. The government was divided into two parts, the "Jamahiriya sector" and the "revolutionary sector". The "Jamahiriya sector" was composed of the General People's Congress, the General People's Committee, and the local Basic People's Congresses. Gaddafi relinquished his position as general secretary of the General People's Congress, as which he was succeeded by Abdul Ati al-Obeidi, who had been prime minister since 1977.

Economic reforms

Remaking of the economy was parallel with the attempt to remold political and social institutions. Until the late 1970s, Libya's economy was mixed, with a large role for private enterprise except in the fields of oil production and distribution, banking, and insurance. But according to volume two of Gaddafi's Green Book, which appeared in 1978, private retail trade, rent, and wages were forms of exploitation that should be abolished. Instead, workers' self-management committees and profit participation partnerships were to function in public and private enterprises.

Military

Wars against Chad and Egypt

In 1977, Gaddafi dispatched his military across the border to Egypt, but Egyptian forces fought back in the Libyan–Egyptian War. Both nations agreed to a ceasefire under the mediation of the President of Algeria Houari Boumediène.[19]

Islamic Legion

In 1972, Gaddafi created the Islamic Legion as a tool to unify and Arabize the region. The priority of the Legion was first Chad, and then Sudan. In Darfur, a western province of Sudan, Gaddafi supported the creation of the Arab Gathering (Tajammu al-Arabi), which according to Gérard Prunier was "a militantly racist and pan-Arabist organization which stressed the 'Arab' character of the province."[20] The two organizations shared members and a source of support, and the distinction between them is often ambiguous.

Janjaweed, a group accused by the US of carrying out a genocide in Darfur in the 2000s, emerged in 1988 and some of its leaders are former legionnaires.[21]

Attempts at nuclear and chemical weapons

International relations

Africa

Gaddafi was a close supporter of Ugandan President Idi Amin.[22]

Gaddafi sent thousands of troops to fight against Tanzania on behalf of Idi Amin. About 600 Libyan soldiers lost their lives attempting to defend the collapsing presidency of Amin. Amin was eventually exiled from Uganda to Libya before settling in Saudi Arabia.[23]

Gaddafi also aided Jean-Bédel Bokassa, the Emperor of the Central African Empire.[23][24] He also intervened militarily in the renewed Central African Republic in 2001 to protect his ally Ange-Félix Patassé. Patassé signed a deal giving Libya a 99-year lease to exploit all of that country's natural resources, including uranium, copper, diamonds, and oil.[25]

Gaddafi supported Soviet protégé Haile Mariam Mengistu.[24]

Normalization of international relations (2003–2010)

In December 2003, Libya announced that it had agreed to reveal and end its programs to develop weapons of mass destruction and to renounce terrorism, and Gaddafi made significant strides in normalizing relations with western nations. He received various Western European leaders as well as many working-level and commercial delegations, and made his first trip to Western Europe in 15 years when he traveled to Brussels in April 2004. Libya responded in good faith to legal cases brought against it in U.S. courts for terrorist acts that predate its renunciation of violence. Claims for compensation in the Lockerbie bombing, LaBelle disco bombing, and UTA 772 bombing cases are ongoing. The U.S. rescinded Libya's designation as a state sponsor of terrorism in June 2006. In late 2007, Libya was elected by the General Assembly to a nonpermanent seat on the United Nations Security Council for the 2008–2009 term. Currently, Operation Enduring Freedom - Trans Sahara is being fought in Libya's portion of the Sahara Desert.

Purification laws

In 1994, the General People's Congress approved the introduction of "purification laws" to be put into effect, punishing theft by the amputation of limbs, and fornication and adultery by flogging.[26] Under the Libyan constitution, homosexual relations are punishable by up to five years in jail.[27]

Opposition, coups and revolts

Throughout his long rule, Gaddafi had to defend his position against opposition and coup attempts, emerging both from the military and from the general population. He reacted to these threats on one hand by maintaining a careful balance of power between the forces in the country, and by brutal repression on the other. Gaddafi successfully balanced the various tribes of Libya one against the other by distributing his favours. To forestall a military coup, he deliberately weakened the Libyan Armed Forces by regularly rotating officers, relying instead on loyal elite troops such as his Revolutionary Guard Corps, the special-forces Khamis Brigade and his personal Amazonian Guard, even though emphasis on political loyalty tended, over the long run, to weaken the professionalism of his personal forces. This trend made the country vulnerable to dissension at a time of crisis, as happened during early 2011.

Political repression and "Green Terror"

Political unrest during the 1990s

In the 1990s, Gaddafi's rule was threatened by militant Islamism. In October 1993, there was an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Gaddafi by elements of the Libyan army. In response, Gaddafi used repressive measures, using his personal Revolutionary Guard Corps to crush riots and Islamist activism during the 1990s. Nevertheless, Cyrenaica between 1995 and 1998 was politically unstable, due to the tribal allegiances of the local troops.[28]

2011 civil war and collapse of Gaddafi's government

A renewed serious threat to the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya came in February 2011, with the Libyan Civil War. The novelist Idris Al-Mesmari was arrested hours after giving an interview with Al Jazeera about the police reaction to protests in Benghazi on 15 February.

Inspiration for the unrest is attributed to the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, connecting it with the wider Arab Spring.[29] On 22 February, The Economist described the events as an "uprising that is trying to reclaim Libya from the world's longest-ruling autocrat."[30] Gaddafi had referred to the opposition variously as "rats", "cockroaches", and "drugged kids" and accused them of being part of al-Qaeda.[31][32] In the east, the National Transitional Council was established in Benghazi.

Gaddafi's son, Khamis, controlled the well-armed Khamis Brigade and alleged to possess large number of mercenaries.[33][34] Some Libyan officials had sided with the protesters and requested help from the international community to bring an end to the massacres of civilians. The government in Tripoli had lost control of half of Libya by the end of February,[35][36] but as of mid-September Gaddafi remained in control of several parts of Fezzan. On 21 September, the forces of NTC captured Sabha, the largest city of Fezzan, reducing the control of Gaddafi to limited and isolated areas.

Many nations condemned Gaddafi's government over its use of force against civilians. Several other nations allied with Gaddafi called the uprising and intervention a "plot" by Western powers to loot Libya's resources.[37] The United Nations Security Council passed a resolution to enforce a no-fly zone over Libyan airspace on 17 March 2011.[38]

The UN resolution authorised air-strikes against Libyan ground troops and warships that appeared to threaten civilians.[39] On 19 March, the no-fly zone enforcement began, with French aircraft undertaking sorties across Libya and a naval blockade by the British Royal Navy.[40] Eventually, the aircraft carriers يوإسإس Enterprise and Charles de Gaulle arrived off the coast and provided the enforcers with a rapid-response capability. U.S. forces named their part of the enforcement action Operation Odyssey Dawn, meant to "deny the Libyan regime from using force against its own people".[41] said U.S. Vice Admiral William E. Gortney. More than 110 "Tomahawk" cruise missiles were fired in an initial assault by U.S. warships and a British submarine against Libyan air defences.[42]

The last government holdouts in Sirte finally fell to anti-Gaddafi fighters on 20 October 2011, and, following the controversial death of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya was officially declared "liberated" on 23 October 2011, ending 42 years of Gaddafi's leadership in Libya.[43]

Political scientist Riadh Sidaoui suggested in October 2011 that Gaddafi "has created a great void for his exercise of power: there is no institution, no army, no electoral tradition in the country", and as a result, the period of transition would be difficult in Libya.[44]

رأي

رأيي في ما حدث ويحدث في ليبيا: القذافي كان ديكتاتوراً ظالماً، ولكنه خدم بلده بإخلاص وذكاء وطموح مفرط حتى مطلع الألفية. وخدم الأقليات المسلمة حول العالم كما لم يخدمها حاكم مسلم من قبل. وتعاطف ودعم نضالات الشعوب المضطهدة بغض النظر عن دينها. نذكر له النهر الصناعي الذي يمد ليبيا حتى اليوم بنحو 98% من احتياجاتها من ماء الشرب، بالرغم من القصف الجنوني لمنشآته في 2011. يذكر له كل الأفارقة خلق "الاتحاد الأفريقي" وتجمع دول الساحل والصحراء. الاتفاقيات الأربع التي ترعى حقوق المسلمين في الفلبين كلها تم توقيعها في طرابلس. زعيم جبهة تحرير المورو في الفلبين اليوم اسمه قذافي. أحد زعماء الحزب الإسلامي في ماليزيا اسمه "قذافي جنجلاني". واليوم يحاول البعض استبدال الدعم الليبي لمسلمي مندناو بخلق تنظيمات إرهابية، مثل أبو سياف وداعش الفلبين. ولكن القذافي محى الحياة السياسية من ليبيا، وقضى على أي فرصة لحكم الشعب، على عكس الهدف المعلن للجماهيرية. فانفصل الشعب عن الدولة.

الخروج على القذافي والعمل على الإطاحة به هو أمر مبرر، طالما كان الخروج بدون عمالة للدول الأخرى. ما حدث في 2011 هو هجوم من الناتو على ليبيا، بشراذم من "العملاء" بمختلف الألوان. بعض هؤلاء العملاء كان لصاً سراقاً من أول يوم، والآخر سفاحاً سفاكاً للدماء. الأرواح المزهقة في كل عام منذ 2011 حتى 2018 يفوق كل ما ادعى أعداء القذافي أنه قتلهم طوال عهده. الأموال المنهوبة في كل عام منذ 2011 حتى 2018 يفوق كل ما اتهم البعض نظام القذافي بنهبه. هل أطالب بعودة نظام القذافي؟ بالطبع لا. ولكني أحاول شرح ما جرى ويجري. ففي النهاية لا توجد ملائكة لتقود البلاد، ولكن يجب أن نعي أن ليس بيننا من هو منزه عن الخطأ. ولكن خطأ عن خطأ يختلف كثيراً. الديكتاتورية خطيئة لا تغتفر. ولكن العمالة خطيئة لا تفوقها خطيئة. وكما ترون فقد انزلقنا في جبر الخطايا، والمفاضلة بين مختلف الخطايا.

حين ينهار العمران في بلد لعشر سنوات، فاعلم أن جيلاً كاملاً قد شب بلا أي تعليم. وسيدمر المجتمع للسبعين سنة التالية. هذا ما يحدث في أرجاء العالم العربي. والانهيار إما أن يكون بسبب الحرب أو بسبب حكام ضالعين. ذلك الجيل لن يعرف القراءة حتى يقرأ كتب أي اتجاه ديني أو سياسي - سيكون نهباً للأفاقين والعملاء.

انظر أيضاً

- Day of Revenge (Libya)

- Politics of Libya under Muammar Gaddafi

- Foreign relations of Libya under Muammar Gaddafi

- Human rights in Libya

- Institutions of governance under Gaddafi

- Basic People's Congress (country subdivision)

- Basic People's Congress (political)

- General People's Committee

- General People's Congress (Libya)

- ما بعد القذافي

الهامش

- ^ أ ب "Libya: History". GlobalEDGE (via Michigan State University). Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Housing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "African Countries by GDP Per Capita > GDP Per Capita (most recent) by Country". NationMaster. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Comparative Criminology – Libya". Crime and Society. Archived from the original on 7 أغسطس 2011. Retrieved 24 يوليو 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Genugten, Saskia van (2016-05-18). Libya in Western Foreign Policies, 1911–2011 (in الإنجليزية). Springer. p. 139. ISBN 9781137489500.

- ^ Crawford, Alex (23 March 2011). "Evidence Of Massacre By Gaddafi Forces". Sky News. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McGreal, Chris (2011-03-30). "Undisciplined Libyan rebels no match for Gaddafi's forces". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ^ "Western nations step up efforts to aid Libyan rebels". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ^ "America's secret plan to arm Libya's rebels". The Independent (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2011-03-07. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ^ "France sent arms to Libyan rebels". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ^ "Libya crisis: Col Gaddafi vows to fight a 'long war'". BBC News. 1 September 2011.

- ^ أ ب Kadhafi : "je suis un opposant à l'échelon mondial" (in French). Paris: P.-M. Favre. 1984. p. 104.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Anti-Gadhafi forces take over port in Sirte". CNN. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ General People's Congress declaration (2 March 1977) at EMERglobal Lex for the Edinburgh Middle East Report. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ "ICL - Libya - Declaration on the Establishment of the Authority of the People". Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Geographical Names, "اَلْجَمَاهِيرِيَّة اَلْعَرَبِيَّة اَللِّيبِيَّة اَلشَّعْبِيَّة اَلإِشْتِرَاكِيَّة: Libya", Geographic.org. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Protesters Die as Crackdown in Libya Intensifies, The New York Times, 20 February 2011; accessed 20 February 2011.

- ^ Human Development Index (HDI) – 2010 Rankings, United Nations Development Programme

- ^ "Eugene Register-Guard - Google News Archive Search". Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Prunier, Gérard. Darfur: The Ambiguous Genocide. p. 45.

- ^ de Waal, Alex (5 August 2004). "Counter-Insurgency on the Cheap". London Review of Books. 26 (15).

- ^ Amin, Idi; Turyahikayo-Rugyema, Benoni (1998). Idi Amin Speaks – An Annotated Selection of His Speeches.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب Stanik, Joseph T. (2003). El Dorado Canyon – Reagan's Undeclared War with Qaddafi.

- ^ أ ب Davis, Brian Lee (1990). Qaddafi, Terrorism, and the Origins of the U.S. Attack on Libya. p. 16.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHarvard%2520for%2520Tyrants - ^ Stokke, Hugo; Suhrke, Astri; Tostensen, Arne (1997). Human Rights in Developing Countries: Yearbook 1997. The Hague: Kluwer International. p. 241. ISBN 978-90-411-0537-0.

- ^ "Being gay under Gaddafi". Gaynz.com. Archived from the original on 2 نوفمبر 2011. Retrieved 1 سبتمبر 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Martínez, Luis (2007). The Libyan Paradox. Columbia University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-231-70021-4.

Cordesman, Anthony H. (2002). A Tragedy of Arms – Military and Security Developments in the Maghreb. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-275-96936-3. - ^ Shadid, Anthony (18 February 2011). "Libya Protests Build, Showing Revolts' Limits". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Time to Leave – A Correspondent Reports from the Border Between Libya and Egypt". The Economist. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi: 'I Will Not Give Up', 'We Will Chase the Cockroaches'". The Times. 22 February 2011.

- ^ Harvey, Benjamin; Mazen, Maram; Derhally, Massoud A. (25 February 2011). "Qaddafi's Grip on Power Weakens on Loss of Territory". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

Qaddafi, speaking by telephone on state television yesterday, blamed the uprising against his 41-year rule on 'drugged kids' and al-Qaeda.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peter Gwin (31 August 2011). "Former Qaddafi Mercenaries Describe Fighting in Libyan War". The Atlantic. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ [http:// www.economist.com/node/18239888 "Endgame in Tripoli"]. The Economist. 24 February 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Gaddafi Defiant as State Teeters". Al Jazeera English. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Middle East and North Africa Unrest". BBC News. 24 February 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Casey, Nicholas; de Córdoba, José (26 February 2011). "Where Gadhafi's Name Is Still Gold". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Security Council Approves 'No-Fly Zone' over Libya, Authorizing 'All Necessary Measures' to Protect Civilians in Libya, By a Vote of Ten For, None Against, with Five Abstentions". United Nations. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "U.N. no-fly zone over Libya: what does it mean?".

- ^ "French Fighter Jets Deployed over Libya". CNN. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Gunfire, explosions heard in Tripoli". CNN. 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya Live Blog – March 19". Al Jazeera. 19 مارس 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "UPDATE 4-Libya declares nation liberated after Gaddafi death". Reuters. 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Libye: "Mouammar Kadhafi avait choisi la voie suicidaire dès février"" [Libya: "Muammar Gaddafi had chosen the path of suicide in February"]. 20 minutes (in French). 20 October 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

وصلات خارجية

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4380360.stm

- Qaddafi, Libya, and the United States from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- The Road to people's authority: a collection of historical speeches and documents Includes the initial RCC communique and the "Declaration of Peoples Authority".

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 errors: deprecated parameters

- CS1 errors: URL

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- تاريخ ليبيا في عهد معمر القذافي

- القرن العشرون في ليبيا

- القرن 21 في ليبيا

- مقالات تحتوي مقاطع ڤيديو

- دول شمولية