حقوق الإنسان في ليبيا

| ليبيا |

هذه المقالة هي جزء من سلسلة: |

|

|

|

الدستور

السلطة التنفيذية

السلطة التشريعية

السلطة القضائية

التقسيمات

الانتخابات

السياسة الخارجية

|

|

دول أخرى • أطلس بوابة السياسة |

Human rights in Libya is the record of human rights upheld and violated in various stages of Libya's history. The Kingdom of Libya, from 1951 to 1969, was heavily influenced and educated by the British and Y.R.K companies. Under the King, Libya had a constitution. The kingdom, however, was marked by a feudal regime, where Libya had a low literacy rate of 10%, a low life expectancy of 57 years, and 40% of the population lived in shanties, tents, or caves.[1] Illiteracy and homelessness were chronic problems during this era, when iron shacks dotted many urban centres on the country.[2]

From 1969 to 2011, the history of Libya was marked by the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (where jamahiriya means "state of the masses"), a "direct democracy" political system established by Muammar Gaddafi,[3] who nominally stepped down from power in 1977, but remained an unofficial "Brother Leader" until 2011. Under the Jamahiriya, Libya maintained a relatively high quality of life due to its nationalized oil wealth and small population, coupled with government policies that undid the social injustices of the Senussi era. The country's literacy rate rose to 90%, and welfare systems were introduced that allowed access to free education, free healthcare, and financial assistance for housing. In 2008, the General People's Congress had declared the Great Green Charter of Human Rights of the Jamahiriyan Era.[4] The Great Manmade River was also built to allow free access to fresh water across large parts of the country.[1] In addition, illiteracy and homelessness had been "almost wiped out,"[2] and financial support was provided for university scholarships and employment programs,[5] while the nation as a whole remained debt-free.[6] As a result, Libya's Human Development Index in 2010 was the highest in Africa and greater than that of Saudi Arabia.[1]

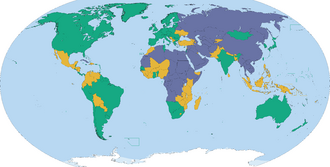

Throughout Gaddafi's rule, international non-governmental organizations routinely characterized Libya's human rights situation as poor, citing systematic abuses such as political repression, restrictions on political freedoms and civil liberties, and arbitrary imprisonment; Freedom House's annual Freedom in the World report consistently gave it a ranking of "Not Free" and gave Libya their lowest possible rating of "7" in their evaluations of civil liberties and political freedoms from 1989 to 2010. Gaddafi also publicly bragged about sending hit squads to assassinate exiled dissidents, and Libyan state media openly announced bounties on the heads of political opponents. The Gaddafi regime was also accused of the 1996 Abu Salim prison massacre. In 2010, Amnesty International, published a critical report on Libya, raising concerns about cases of enforced disappearances and other human rights violations that remained unresolved, and that Internal Security Agency members implicated in those violations continued to operate with impunity.[7] In January 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council published a report analysing the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya's human rights record with input from member nations, most of which (including many European and most Asian, African and South American nations) generally praised the country's progressive efforts in human rights, though some (particularly Australia, France, Israel, Switzerland, and the United States) raised concerns about human rights abuses concerning cases of disappearance and torture, and restrictions on free press and free association; Libya agreed to investigate cases involving disappearance and torture, and to repeal any laws criminalizing political expression or restricting a free independent press, and affirmed that it had an independent judiciary.[8]

في عهد القذافي

اللجان الثورية

Foreign languages and migrant workers

Criticism of allegations

محاكمة الإيدز

مذبحة سجن أبو سليم

التعذيب

في 28 نوفمبر 2021، اتّهم القضاء الفرنسي شركة نيكسا تكنولوجي الفرنسية، المتهمة ببيع معدات مراقبة للنظام المصري كانت ستمكنه من تعقب معارضين، في أكتوبر "بالتواطؤ في أعمال تعذيب واختفاء قسري". وأصدرت قرار الاتهام هذا قاضية التحقيق المكلفة التحقيقات في 12 أكتوبر، بعد حوالى أربعة أشهر من اتهام أربعة مديرين تنفيذيين ومسؤولين في الشركة، بحسب هذا المصدر. وأكد مصدر قضائي هذه المعلومات. وفي اتصال مع وكالة فرانس برس، رفض محامي نيكسا تكنولوجي فرنسوا زيمراي الإدلاء بأي تعليق.[9]

في 2017، فتح تحقيق قضائي بعد شكوى قدمتها الفدرالية الدولية لحقوق الإنسان ورابطة حقوق الإنسان بدعم من مركز القاهرة لدراسات حقوق الإنسان. واستندت المنظمات إلى تحقيق لمجلة تيليراما كشف عن بيع "نظام تنصت بقيمة عشرة ملايين يورو لمكافحة - رسمياً - "الإخوان المسلمين"، المعارضة الإسلامية في مصر، في مارس 2014. ويتيح هذا البرنامج المسمى "سيريبرو" إمكان تعقب الاتصالات الإلكترونية لهدف ما في الوقت الفعلي، من عنوان بريد إلكتروني أو رقم هاتف على سبيل المثال.

واتهمت المنظمات غير الحكومية هذا البرنامج بأنه خدم موجة القمع ضد معارضي عبد الفتاح السيسي، التي أسفرت حسب مركز القاهرة لدراسات حقوق الإنسان عن "أكثر من 40 ألف معتقل سياسي في مصر". ويهدف التحقيق الذي أجراه "قطب الجرائم ضد الإنسانية" في المحكمة القضائية في باريس إلى تحديد ما إذا كان يمكن إثبات صلة بين استخدام المراقبة والقمع.

في 16 و17 ينيو 2021، قام قضاة التحقيق بوحدة التحقيق في الجرائم ضد الإنسانية وجرائم الحرب التابعة لمحكمة باريس القضائية، بتوجيه اتهامات بحق أربعة من المدراء التنفيذيين في شركتي أمسيس ونكسا تكنولوجي. تضمنت هذه الاتهامات التواطؤ في جريمة التعذيب في حق الجانب الليبي من التحقيقات، والتواطؤ في جريمتي التعذيب والإختفاء القسري في حق الجانب المصري. وقد تم اتهام الشركتين بتزويد الأنظمة الإستبدادية في ليبيا ومصر بتكنولوجيا المراقبة.[10]

والمصدر الأساسي لتلك الاتهامات هو شكوتان منفصلتان قدمهما كل من الفدرالية الدولية لحقوق الإنسان (FIDH) والرابطة الفرنسية لحقوق الإنسان (LDH)، اتهمتا فيهما الشركات السابق ذكرها ببيع تكنولوجيا المراقبة إلى نظام معمر القذافي الليبي (عام 2007). ونظام عبد الفتاح السيسي المصري (عام 2014).

في 19 أكتوبر 2011، قامت منظماتنا برفع أول شكوى ضد أمسيس بعد الكشف عن المعلومات التي تم نشرها في وال ستريت جورنال وويكيليكس. وفي 2013، رافقت الفدرالية الدولية لحقوق الإنسان بعض الضحايا الليبيين لنظام القذافي، والذين قدموا شهاداتهم أمام القضاة حول الطريقة التي تم تحديد هوياتهم بها ومن ثم اعتقالهم وتعذيبهم ، بعد إخضاعهم للمراقبة من قبل أجهزة الأمن الليبية.

وفي 9 نوفمبر 2017، قامت الفدرالية الدولية لحقوق الإنسان والرابطة الفرنسية لحقوق الإنسان، بدعم من مركز القاهرة لدراسات حقوق الإنسان، بتقديم شكوى إلي وحدة الجرائم ضد الإنسانية وجرائم الحرب التابعة لمكتب المدعي العام بباريس بخصوص مشاركة نفس الشركة (والتي عُرفت باسم نكسا تكنولوجي منذ ذلك الحين) في العمليات القمعية التي نفذها نظام السيسي، من خلال بيع معدات المراقبة. وقد جاء هذا الطلب بفتح تحقيق جديد في أفعال التواطؤ في جريمة التعذيب والإختفاء القسري المرتكبة في مصر عقب ما نشرته صحيفة تيليرما الفرنسية في يوليو 2017، والذي بموجبه قامت شركة أمسيس "بتغيير اسمها وحملة أسهمها لبيع خدماتها إلى الحكومة المصرية الجديدة - دون أن تجد الدولة الفرنسية مشكلة في ذلك".

وفي مايو 2017، تم وضع شركة أمسيس تحت صفة الشاهد المتعاون[11] بتهمة التواطؤ في أعمال التعذيب المرتكبة في ليبيا بين عامي 2007 و2011.

الحرب الأهلية

Women's rights

Libyan coastguard's violation of migrants' rights

Historical situation

| Historical ratings | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

International treaties

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- 1.^ Note that the "Year" signifies the year the report was issued. The information for the year marked 2009 covers the year 2008, and so on.

- 2.^ As of 1 January.

- 3.^ The 1982 report covers 1981 and the first half of 1982, and the following 1984 report covers the second half of 1982 and the whole of 1983. In the interest of simplicity, these two aberrant "year and a half" reports have been split into three-year-long reports through interpolation.

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت Azad, Sher (22 October 2011). "Gaddafi and the media". Daily News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ أ ب Hussein, Mohamed (21 February 2011). "Libya crisis: what role do tribal loyalties play?". BBC News. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Robbins, James (7 March 2007). "Eyewitness: Dialogue in the desert". BBC News. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ The Great Green Charter of Human Rights of the Jamahiriyan Era Archived 29 مايو 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shimatsu, Yoichi (21 October 2011). "Villain or Hero? Desert Lion Perishes, Leaving West Explosive Legacy". New America Media. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Reason Wafavarova - Reverence for Hatred of Democracy". AllAfrica.com. 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Libya - Amnesty International Report 2010".

Hundreds of cases of enforced disappearance and other serious human rights violations committed in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s remained unresolved, and the Internal Security Agency (ISA), implicated in those violations, continued to operate with impunity.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةohchr - ^ "اتهام "نيكسا تكنولوجي" الفرنسية "بالتواطؤ في أعمال تعذيب" في قضية بيع معدات مراقبة لمصر". فرانس 24. 2021-11-28. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ "المراقبة والتعذيب في مصر وليبيا: توجيه الإتهام قانونياً إلي المدراء التنفيذيين لشركتى Amesys و Nexa Technologies". حركة عالمية لحقوق الإنسان. 2021-06-22. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ صطلح "الشاهد المتعاون" ، الذي يمكن أن يسبق لائحة الاتهام الرسمية، يمكن تطبيقه على أي شخص متهم من قبل أحد الشهود، أو تشير الأدلة إلى أنه ربما كان متواطئًا، أو جانيًا أو مشاركًا في الجرائم التي يتم التحقيق فيها من قبل قاضي التحقيق.

- ^ al-Gattani, Ali (4 February 2014). "Shahat slams GNC". Magharebia. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Freedom in the World 2016, Freedom House. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 1. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Paris, 9 December 1948". Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 2. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. New York, 7 March 1966". Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 3. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. New York, 16 December 1966". Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 4. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. New York, 16 December 1966". Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 5. Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. New York, 16 December 1966". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 6. Convention on the non-applicability of statutory limitations to war crimes and crimes against humanity. New York, 26 November 1968". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 7. International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid. New York, 30 November 1973". Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 8. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. New York, 18 December 1979". Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 9. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. New York, 10 December 1984". Archived from the original on 8 November 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 11. Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York, 20 November 1989". Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 12. Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty. New York, 15 December 1989". Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 13. International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families. New York, 18 December 1990". Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 8b. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. New York, 6 October 1999". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 11b. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict. New York, 25 May 2000". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 11c. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. New York, 25 May 2000". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 15. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York, 13 December 2006". Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 15a. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York, 13 December 2006". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 16. International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. New York, 20 December 2006". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 3a. Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. New York, 10 December 2008". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations. "United Nations Treaty Collection: Chapter IV: Human Rights: 11d. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a communications procedure . New York, 19 December 2011. New York, 10 December 2008". Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

وصلات خارجية

- Amnesty International. LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA.BRIEFING TO THE UN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, 2007

- US Department of State.2008 Human Rights Report: Libya

- Library of Congress country study

- Censorship in Libya - IFEX

- 2012 Annual Report, by Amnesty International

- Freedom in the World 2011 Report, by Freedom House

- World Report 2012, by Human Rights Watch

This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.