كلوج-ناپوكا

كلوج-ناپوكا

Cluj-Napoca | |

|---|---|

From top and left: Cluj-Napoca panorama • Romanian National Opera • Tailors' Bastion • St. Michael's Church • Cluj Arena | |

| الكنية: | |

Location in Cluj County | |

| الإحداثيات: 46°46′N 23°35′E / 46.767°N 23.583°E | |

| Country | |

| المنطقة | ترانسلڤانيا |

| المقاطعة | |

| Founded | 1213 (first official record as Clus) |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة (2020–2024) | Emil Boc[3] (PNL) |

| • Deputy Mayor | Dan Tarcea (PNL) |

| • Deputy Mayor | Emese Oláh (UDMR) |

| • City Manager | Gheorghe Șurubaru (PNL) |

| المساحة | |

| • مدينة ومقر مقاطعة | 179٫5 كم² (69٫3 ميل²) |

| • العمران | 1٬537٫5 كم² (593٫6 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 340 m (1٬120 ft) |

| التعداد | |

| • مدينة ومقر مقاطعة | 324٬576 |

| • Estimate (2016)[6] | 321٬687 |

| • الكثافة | 1٬808/km2 (4٬680/sq mi) |

| • العمرانية | 411٬379[4] |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal Code | 400xyz1 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +40 x642 |

| Car Plates | CJ-N3 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | primariaclujnapoca |

| 1x, y, and z are digits that indicate the street, part of the street, or even the building of the address 2x is a digit indicating the operator: 2 for the former national operator, Romtelecom, and 3 for the other ground telephone networks 3used just on the plates of vehicles that operate only within the city limits (such as trolley buses, trams, utility vehicles, ATVs, etc.) | |

كلوج-ناپوكا (النطق بالرومانية: [ˈkluʒ naˈpoka] (![]() استمع); ألمانية: Klausenburg; مجرية: Kolozsvár, النطق في المجرية: [ˈkoloʒvaːr] (

استمع); ألمانية: Klausenburg; مجرية: Kolozsvár, النطق في المجرية: [ˈkoloʒvaːr] (![]() استمع); اللاتينية القروسطية: Castrum Clus, Claudiopolis; باليديشية: קלויזנבורג, Kloiznburg) تقع شمال-غرب رومانيا وهي عاصمة محافظة كلوج في إقليم ترانسلڤانيا وتعتبر من أهم عواصم التاريخية لهذا الإقليم.

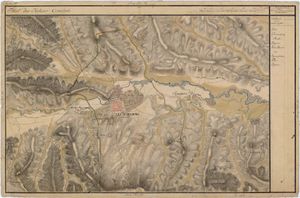

تعتبر مركز إقتصادي وثقافي هام, بالإضافة كونها عقدة مواصلات مهمة في رومانيا. Geographically, it is roughly equidistant from Bucharest (445 كيلومتر (277 ميل)), Budapest (461 km (286 mi)) and Belgrade (483 km (300 mi)). Located in the Someșul Mic river valley, the city is considered the unofficial capital to the historical province of Transylvania. From 1790 to 1848 and from 1861 to 1867, it was the official capital of the Grand Principality of Transylvania.

استمع); اللاتينية القروسطية: Castrum Clus, Claudiopolis; باليديشية: קלויזנבורג, Kloiznburg) تقع شمال-غرب رومانيا وهي عاصمة محافظة كلوج في إقليم ترانسلڤانيا وتعتبر من أهم عواصم التاريخية لهذا الإقليم.

تعتبر مركز إقتصادي وثقافي هام, بالإضافة كونها عقدة مواصلات مهمة في رومانيا. Geographically, it is roughly equidistant from Bucharest (445 كيلومتر (277 ميل)), Budapest (461 km (286 mi)) and Belgrade (483 km (300 mi)). Located in the Someșul Mic river valley, the city is considered the unofficial capital to the historical province of Transylvania. From 1790 to 1848 and from 1861 to 1867, it was the official capital of the Grand Principality of Transylvania.

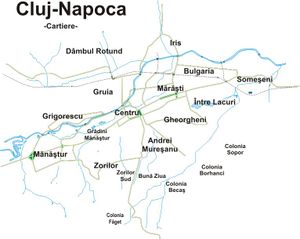

اعتبارا من 2011[تحديث], 324,576 inhabitants lived within the city limits (making it the country's second most populous at the time, after the national capital Bucharest), marking a slight increase from the figure recorded at the 2002 census.[5][7] The Cluj-Napoca metropolitan area has a population of 411,379 people,[4][8] while the population of the peri-urban area (Romanian: zona periurbană) exceeds 420,000 residents.[4][9] The new metropolitan government of Cluj-Napoca became operational in December 2008.[10] According to a 2007 estimate provided by the County Population Register Service, the city hosts a visible population of students and other non-residents—an average of over 20,000 people each year during 2004–2007.[11] The city spreads out from St. Michael's Church in Unirii Square, built in the 14th century and named after the Archangel Michael, the patron saint of Cluj-Napoca.[12] The boundaries of the municipality contain an area of 179.52 متر كيلومربع (69.31 sq mi).

Cluj-Napoca experienced a decade of decline during the 1990s, its international reputation suffering from the policies of its mayor at the time, Gheorghe Funar.[13] Today, the city is one of the most important academic, cultural, industrial and business centres in Romania. Among other institutions, it hosts the country's largest university, Babeș-Bolyai University, with its botanical garden; nationally renowned cultural institutions; as well as the largest Romanian-owned commercial bank.[14][15] Cluj-Napoca held the titles of European Youth Capital in 2015,[16] and European City of Sport in 2018.[17]

التسمية

ناپوكا

On the site of the city was a pre-Roman settlement named Napoca. After the AD 106 Roman conquest of the area, the place was known as Municipium Aelium Hadrianum Napoca. Possible etymologies for Napoca or Napuca include the names of some Dacian tribes such as the Naparis or Napaei, the Greek term napos (νάπος), meaning "timbered valley" or the Indo-European root *snā-p- (Pokorny 971–972), "to flow, to swim, damp".[18]

كلوج

The first written mention of the city's current name – as a Royal Borough – was in 1213 under the Medieval Latin name Castrum Clus.[19] Despite the fact that Clus as a county name was recorded in the 1173 document Thomas comes Clusiensis,[20] it is believed that the county's designation derives from the name of the castrum, which might have existed prior to its first mention in 1213, and not vice versa.[20] With respect to the name of this camp, there are several hypotheses about its origin. It may represent a derivation from the Latin term clausa – clusa, meaning "closed place", "strait", "ravine".[20] Similar meanings are attributed to the Slavic term kluč, meaning "a key"[20] and the German Klause – Kluse (meaning "mountain pass" or "weir").[21] The Latin and Slavic names have been attributed to the valley that narrows or closes between hills just to the west of Cluj-Mănăștur.[20] An alternative proposal relates the name of the city to its first magistrate, Miklus – Miklós / Kolos.[21]

The Hungarian form Kolozsvár, first recorded in 1246 as Kulusuar, underwent various phonetic changes over the years (uar / vár means "castle" in Hungarian); the variant Koloswar first appears in a document from 1332.[22] Its Saxon name Clusenburg/Clusenbvrg appeared in 1348, but from 1408 the form Clausenburg was used.[22] The Romanian name of the city used to be spelled alternately as Cluj or Cluș,[23] the latter being the case in Mihai Eminescu's Poesis.

Other historical names for the city, all related to or derived from "Cluj" in different languages, include Latin Claudiopolis, Italian Clausemburgo,[24] Turkish Kaloşvar[25] and Yiddish קלויזנבורג Kloyznburg or קלאזין Klazin.[23]

الاسم الرسمي الحالي

Napoca, the pre-Roman and Roman name of ancient settlements in the area of the modern city, was added to the historical and modern name of Cluj during Nicolae Ceaușescu's national-communist dictatorship as part of his myth-making efforts.[26] This happened in 1974, when the communist authorities made this nationalist gesture with the goal of emphasising the city's pre-Roman roots.[27][28] The full name of "Cluj-Napoca" is rarely used outside of official contexts.[29]

الكنية

The nickname "treasure city" was acquired in the late 16th century, and refers to the wealth amassed by residents, including in the precious metals trade.[30] The phrase is orașul comoară in Romanian,[31] given in Hungarian as kincses város.[32][33]

عدد السكان

في 2008 كان عدد سكانها 309,300 نسمة حيث هي في المرتبة الثالثة بعد بوخارست و تيميشوارا, يذكر أن حوالي 60.000 من الهنغار يعيشون في هذه المدينة.

التاريخ

الامبراطورية الرومانية

The Roman Empire conquered Dacia in AD 101 and 106, during the rule of Trajan, and the Roman settlement Napoca, established about 106, is first recorded on a milestone discovered in 1758 in the vicinity of the city.[35] Trajan's successor Hadrian granted Napoca the status of municipium as municipium Aelium Hadrianum Napocenses. Later, in the second century AD,[36] the city gained the status of a colonia as Colonia Aurelia Napoca. Napoca became a provincial capital of Dacia Porolissensis and thus the seat of a procurator. The colonia was evacuated in 274 by the Romans.[35] There are no references to urban settlement on the site for the better part of a millennium thereafter.[37]

العصور الوسطى

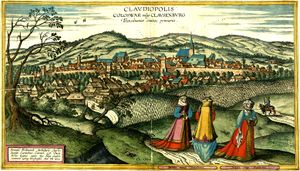

"Claudiopolis, Coloswar vulgo Clausenburg, Transilvaniæ civitas primaria". Gravure[a] of Cluj by Georg Houfnagel (1617) |

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, two groups of buildings existed on the current site of the city: the wooden fortress at Cluj-Mănăștur (Kolozsmonostor) and the civilian settlement developed around the current Piața Muzeului (Museum Place) in the city centre.[20][38] Although the precise date of the conquest of Transylvania by the Hungarians is not known, the earliest Hungarian artifacts found in the region are dated to the first half of the tenth century.[39] In any case, after that time, the city became part of the Kingdom of Hungary. King Stephen I made the city the seat of the castle county of Kolozs, and King Saint Ladislaus I of Hungary founded the abbey of Cluj-Mănăștur (Kolozsmonostor), destroyed during the Tatar invasions in 1241 and 1285.[20] As for the civilian colony, a castle and a village were built to the northwest of the ancient Napoca no later than the late 12th century.[20] This new village was settled by large groups of Transylvanian Saxons, encouraged during the reign of Crown Prince Stephen, Duke of Transylvania.[19] The first reliable mention of the settlement dates from 1275, in a document of King Ladislaus IV of Hungary, when the village (Villa Kulusvar) was granted to the Bishop of Transylvania.[40] On 19 August 1316, during the rule of the new king, Charles I of Hungary, Cluj was granted the status of a city (Latin: civitas), as a reward for the Saxons' contribution to the defeat of the rebellious Transylvanian voivode, Ladislaus Kán.[40]

The couple buried together and known as the Lovers of Cluj-Napoca are believed to have lived between 1450 and 1550.[41][42]

Many craft guilds were established in the second half of the 13th century, and a patrician stratum based in commerce and craft production displaced the older landed elite in the town's leadership.[43] Through the privilege granted by Sigismund of Luxembourg in 1405, the city opted out from the jurisdiction of voivodes, vice-voivodes and royal judges, and obtained the right to elect a twelve-member jury every year.[44] In 1488, King Matthias Corvinus (born in Kolozsvár in 1443) ordered that the centumvirate—the city council, consisting of one hundred men—be half composed from the homines bone conditiones (the wealthy people), with craftsmen supplying the other half; together they would elect the chief judge and the jury.[44] Meanwhile, an agreement was reached providing that half of the representatives on this city council were to be drawn from the Hungarian, half from the Saxon population, and that judicial offices were to be held on a rotating basis.[45] In 1541, Kolozsvár became part of the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (that transformed to Principality of Transylvania in 1570) after the Ottoman Turks occupied the central part of the Kingdom of Hungary; a period of economic and cultural prosperity followed.[45] Although Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvár) served as a political capital for the princes of Transylvania, Cluj (Kolozsvár) enjoyed the support of the princes to a greater extent, thus establishing connections with the most important centres of Eastern Europe at that time, along with Košice (Kassa), Kraków, Prague and Vienna.[44]

القرون 16–18

In terms of religion, Protestant ideas first appeared in the middle of the 16th century. During Gáspár Heltai's service as preacher, Lutheranism grew in importance, as did the Swiss doctrine of Calvinism.[46] By 1571, the Turda (Torda) Diet had adopted a more radical religion, Ferenc Dávid's Unitarianism, characterised by the free interpretation of the Bible and denial of the dogma of the Trinity.[46] Stephen Báthory founded a Catholic Jesuit academy in the city in order to promote an anti-Reform movement; however, it did not have much success.[46] For a year, in 1600–1601, Cluj became part of the personal union of Michael the Brave.[47][48] Under the Treaty of Carlowitz in 1699, it became part of the Habsburg monarchy.[49]

In the 17th century, Cluj suffered from great calamities, suffering from epidemics of the plague and devastating fires.[46] The end of this century brought the end of Turkish sovereignty, but found the city bereft of much of its wealth, municipal freedom, cultural centrality, political significance and even population.[50] It gradually regained its important position within Transylvania as the headquarters of the Gubernium and the Diets between 1719 and 1732, and again from 1790 until the revolution of 1848, when the Gubernium moved to Nagyszeben (Hermannstadt), present-day Sibiu).[51] In 1791, a group of Romanian intellectuals drew up a petition, known as Supplex Libellus Valachorum, which was sent to the Emperor in Vienna. The petition demanded the equality of the Romanian nation in Transylvania in respect to the other nations (Saxon, Szekler and Hungarian) governed by the Unio Trium Nationum, but it was rejected by the Diet of Cluj.[46]

القرن 19

Beginning in 1830, the city became the centre of the Hungarian national movement within the principality.[52] This erupted with the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. The Austrian commander Karl von Urban took control of the city on 18 November 1848, following a battle.[53] Following this, the Hungarian army headed by the Polish general Józef Bem, launched an offensive into Transylvania, recapturing Klausenburg by Christmas 1848.[54]

After the 1848 revolution, an absolutist regime was established, followed by a liberal regime that came to power in 1860. In this latter period, the government granted equal rights to the ethnic Romanians, but only briefly. In 1865, the Diet in Cluj abolished the laws voted in Sibiu (Nagyszeben/Hermannstadt), and proclaimed the 1848 Law concerning the Union of Transylvania with Hungary.[52] A modern university was founded in 1872, with the intention of promoting the integration of Transylvania into Hungary.[55] Before 1918, the city's only Romanian-language schools were two church-run elementary schools, and the first printed Romanian periodical did not appear until 1903.[50]

After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Klausenburg and all of Transylvania were again integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary. During this time, Klausenburg was among the largest and most important cities of the kingdom and was the seat of Kolozs County. Ethnic Romanians in Transylvania suffered oppression and persecution.[56] Their grievances found expression in the Transylvanian Memorandum, a petition sent in 1892 by the political leaders of Transylvania's Romanians to the Austro-Hungarian Emperor-King Franz Joseph. It asked for equal rights with the Hungarians and demanded an end to persecutions and attempts at Magyarisation.[56] The Emperor forwarded the memorandum to Budapest—the Hungarian capital. The authors, among them Ioan Rațiu and Iuliu Coroianu, were arrested, tried and sentenced to prison for "high treason" in Kolozsvár/Cluj in May 1894.[57] During the trial, approximately 20,000 people who had come to Cluj demonstrated on the streets of the city in support of the defendants.[57] A year later, the King gave them pardon upon the advice of his Hungarian prime minister, Dezső Bánffy.[58] In 1897, the Hungarian government decided that only Hungarian place names should be used and prohibited the use of the German or Romanian versions of the city's name on official government documents.[59]

القرن العشرون

In the autumn of 1918, as World War I drew to a close, Cluj became a centre of revolutionary activity, headed by Amos Frâncu. On 28 October 1918, Frâncu made an appeal for the organisation of the "union of all Romanians".[60] Thirty-nine delegates were elected from Cluj to attend the proclamation of the union of Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romania in the Great National Assembly of Alba Iulia on 1 December 1918;[60] the transfer of sovereignty was formalised by the Treaty of Trianon in June 1920.[61] The interwar years saw the new authorities embark on a "Romanianisation" campaign: a Capitoline Wolf statue donated by Rome was set up in 1921; in 1932 a plaque written by historian Nicolae Iorga was placed on Matthias Corvinus's statue, emphasising his Romanian paternal ancestry; and construction of an imposing Orthodox cathedral began, in a city where only about a tenth of the inhabitants belonged to the Orthodox state church.[62] This endeavour had only mixed results: by 1939, Hungarians still dominated local economic and (to a certain extent) cultural life: for instance, Cluj had five Hungarian daily newspapers and just one in Romanian.[62]

In 1940, Cluj, along with the rest of Northern Transylvania, became part of Miklós Horthy's Hungary through the Second Vienna Award arbitrated by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.[63][64][65] After the Germans occupied Hungary in March 1944 and installed a puppet government under Döme Sztójay,[66][67] they forced large-scale antisemitic measures in the city. The headquarters of the local Gestapo were located in the New York Hotel. That May, the authorities began the relocation of the Jews to the Iris ghetto.[64] Liquidation of the 16,148 captured Jews occurred through six deportations to Auschwitz in May–June 1944.[64] Despite facing severe sanctions from the Hungarian administration, some Jews escaped across the border to Romania, with the assistance of intellectuals such as Emil Hațieganu, Raoul Șorban, Aurel Socol and Dezső Miskolczy, as well as various peasants from Mănăștur.[64]

On 11 October 1944 the city was captured by Romanian and Soviet troops.[64][68] It was formally restored to the Kingdom of Romania by the Treaty of Paris in 1947. On 24 January 6 March and 10 May 1946, the Romanian students, who had come back to Cluj after the restoration of northern Transylvania, rose against the claims of autonomy made by nostalgic Hungarians and the new way of life imposed by the Soviets, resulting in clashes and street fights.[69]

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 produced a powerful echo within the city; there was a real possibility that demonstrations by students sympathising with their peers across the border could escalate into an uprising.[70][71] The protests provided the Romanian authorities with a pretext to speed up the process of "unification" of the local Babeș (Romanian) and Bolyai (Hungarian) universities,[72] allegedly contemplated before the 1956 events.[73][74] Hungarians remained the majority of the city's population until the 1960s. Then Romanians began to outnumber Hungarians,[75] due to the population increase as a result of the government's forced industrialisation of the city and new jobs.[76] During the Communist period, the city recorded a high industrial development, as well as enforced construction expansion.[76] On 16 October 1974, when the city celebrated 1850 years since its first mention as Napoca, the Communist government changed the name of the city by adding "Napoca" to it.[28]

ثورة 1989 وما بعدها

During the Romanian Revolution of 1989, Cluj-Napoca was one of the scenes of the rebellion: 26 were killed and approximately 170 injured.[77] After the end of totalitarian rule, the nationalist politician Gheorghe Funar became mayor and governed for the next 12 years. His tenure was marked by strong Romanian nationalism and acts of ethnic provocation against the Hungarian-speaking minority. This deterred foreign investment;[78] however, in June 2004, Gheorghe Funar was voted out of office, and the city entered a period of rapid economic growth.[78] From 2004 to 2009, the mayor was Emil Boc, concurrently president of the Democratic Liberal Party. He went on to be elected as prime minister, returning as mayor in 2012.[79][80]

الجغرافيا

البلدات المحيطة

المناخ

| بيانات المناخ لـ كلوج-ناپوكا | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 14.0 (57.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.5 (90.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.0 (98.6) |

38.0 (100.4) |

33.7 (92.7) |

32.6 (90.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 0.3 (32.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

20.7 (69.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.8 (35.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | −34.2 (−29.6) |

−32.5 (−26.5) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

0.4 (32.7) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−22.3 (−8.1) |

−27.9 (−18.2) |

−34.2 (−29.6) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 24 (0.9) |

20 (0.8) |

22 (0.9) |

48 (1.9) |

69 (2.7) |

95 (3.7) |

81 (3.2) |

60 (2.4) |

36 (1.4) |

31 (1.2) |

30 (1.2) |

32 (1.3) |

548 (21.6) |

| متوسط هطول الثلج cm (inches) | 6.0 (2.4) |

11.5 (4.5) |

5.8 (2.3) |

1.3 (0.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (0.2) |

2.6 (1.0) |

5.8 (2.3) |

33.5 (13.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 91 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 70.9 | 98.8 | 165.2 | 174.7 | 230.8 | 238.6 | 273.8 | 261.6 | 204.8 | 166.2 | 74.9 | 54.7 | 2٬015 |

| Source 1: NOAA[81] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Romanian National Statistic Institute (extremes 1901–2000)[82] | |||||||||||||

القانون والحكم

الادارة

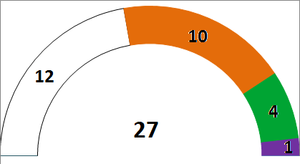

| Party | Seats | Current Council | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Liberal Union | 12 | |||||||||||||

| Democratic Liberal Party | 10 | |||||||||||||

| Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania | 4 | |||||||||||||

| People's Party – Dan Diaconescu | 1 | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population of Cluj-Napoca | |||||||||||||

| Year | Population | %± | Romanians | Hungarians | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1453 est. | 6,000[83] | — | n/a | n/a | |||||||||

| 1703 | 7,500[84] | 25% | n/a | n/a | |||||||||

| 1714 | 5,000[85] | −33.3% | n/a | n/a | |||||||||

| 1770 | 10,500[86] | 110% | n/a | n/a | |||||||||

| 1785 | 9,703[84][87] | −7.6% | n/a | n/a | |||||||||

| 1787 | 10,476[84][87] | 7.9% | n/a | n/a | |||||||||

| 1835 | 14,000[84][88] | 33.6% | n/a | n/a | |||||||||

| 1850 | 19,612 | 40% | 21.0% | 62.8% | |||||||||

| 1880 | 32,831 | 67.4% | 17.1% | 72.1% | |||||||||

| 1890 | 37,184 | 13.2% | 15.2% | 79.1% | |||||||||

| 1900 | 50,908 | 36.9% | 14.1% | 81.1% | |||||||||

| 1910 census[b] | 62,733 | 23.2% | 14.2% | 81.6% | |||||||||

| 1920 | 85,509 | 36.3% | 34.7% | 49.3% | |||||||||

| 1930 census | 100,844[89] | 17.9% | 34.6% | 47.3% | |||||||||

| 1941[c][d] | 114,984 | 14% | 9.8% | 85.7% | |||||||||

| 1948 census | 117,915 | 2.5% | 40% | 57% | |||||||||

| 1956 census[e] | 154,723 | 31.2% | 47.8% | 47.9% | |||||||||

| 1966 census | 185,663 | 20% | 56.5% | 41.4% | |||||||||

| 1977 census | 262,858 | 41.5% | 65.8% | 32.8% | |||||||||

| 1992 census | 328,602 | 25% | 76.6% | 22.7% | |||||||||

| 2002 census | 317,953[7] | −3.2% | 79.4% | 19.0% | |||||||||

| 2011 census[f] | 324,576[5][4][90] | 2.1% | 81.5% | 16.4% | |||||||||

|

Source (if not otherwise specified): | |||||||||||||

الجالية المجرية

Economy

الفنون والثقافة

الفنون البصرية

الفنون الأدائية

العمارة المعاصرة

الإعلام والثقافة الشعبية

التعليم

العلاقات الدولية

البلدات التوأم – المدن الشقيقة

Cluj-Napoca is twinned with:[92]

|

Footnotes

a.^ The engraving, dating back to 1617, was executed by Georg Houfnagel after the painting of Egidius van der Rye (the original was done in the workshop of Braun and Hagenberg).

b.^ After Transylvania united with Romania in 1918–1920, an exodus of Hungarian inhabitants occurred. Also, the city grew and many people moved in from the surrounding area and Cluj County as a whole, populated largely by Romanians.

c.^ In August 1940, as the second Vienna Award transferred the northern half of Transylvania to Hungary, an exile of Romanian inhabitants began.

d.^ The 1941 Hungarian census is considered unreliable by most historians. In 1941, Cluj had 16,763 Jews. They were forced into ghettos in 1944 by the Hungarian authorities and deported to Auschwitz in May–June 1944.

e.^ In the 1960s a determined policy of industrialisation was initiated. Many people from the surrounding rural areas (largely Romanian) moved into the city, giving Cluj a Romanian majority.

f.^ Data refer to those for whom ethnicity is available, and do not include the 23,165 individuals (7.1% of the city's population) for whom such data are unavailable.

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ "Portretul unui oraș" (in الرومانية). Clujeanul. 21 September 2007. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ "A kincses város" (in الهنغارية). UFI. December 2004. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ "Results of the 2020 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Retrieved 11 يونيو 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Rezultate definitive ale Recensământului Populației și Locuințelor – 2011 – analiza". Cluj County Regional Statistics Directorate. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-05.[dead link] خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "INSSE-Cluj-2011-analiza" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب ت "Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele finale ale Recensământului Populației și Locuințelor – 2011". Cluj County Regional Statistics Directorate. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-05.[dead link] خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "INSSE-Cluj-2011" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ "Populaţia României pe localitati la 1 ianuarie 2016" (in الرومانية). INSSE. 6 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ أ ب "Municipiul Cluj-Napoca (data based on the 2002 census)" (in الرومانية). Fundația Jakabffy Elemér. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "Zona Metropolitana Urbana" (in الرومانية). CJ Cluj. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ "Zona Metropolitană Urbană și Strategii de Dezvoltare a Zonei Metropolitane Cluj-Napoca" (in الرومانية). Cluj County Council. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "Asociația Metropolitană e "la cheie". Mai trebuie banii" (in الرومانية). Ziua de Cluj. 9 January 2009. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ^ "Wanted: clujeanul verde" (in الرومانية). Foaia Transilvană. 6 March 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "Catedrala "Sf. Mihail"" (in الرومانية). Clujonline.com. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "Cluj: Buzz grips university town". Financial Times. 6 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ "Five alive – New regions – Five territories to watch". Monocle. Vol. 1, no. 9. December 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Alexandra Groza (8 January 2008). "Presa britanică: "Clujul, campion mondial la dezvoltare"" (in الرومانية). Clujeanul. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "cluj2015.eu". www.cluj2015.eu.

- ^ Raluca Sas (6 December 2017). "Cluj-Napoca a câștigat titlul de "Oraș European al Sportului 2018"". monitorulcj.ro (in الرومانية).

- ^ Lukács 2005, p.14

- ^ أ ب "O istorie inedită a Clujului – Cetatea coloniștilor sași" (in الرومانية). ClujNet.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Lazarovici et al. 1997, p.32 (3.1 De la Napoca romană la Clujul medieval)

- ^ أ ب Gaal, György (19 July 2000). "Kolozsvári kronológia – Kolozsvár kétezer esztendeje dátumokban" (in الهنغارية). Szabadság. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ أ ب Asztalos, Lajos (4 August 2003). "Kolozsvár neve" (in الهنغارية). Szabadság. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ أ ب Szabó, Attila m. "Dicționar de localități din Transilvania" (in الرومانية). Archived from the original on 22 August 2010. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Le Vie d'Italia, vol. 46/1940, issues 7-12, p. 1172

- ^ Gönül Pultar, Kimlikler lütfen: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nde kültürel kimlik arayışı ve temsili, p. 62. Ankara: ODTÜ Yayıncılık, 2009, ISBN 978-994-434478-4

- ^ Pippidi, Andrei (2006). "Historical Memory and Legislative Changes in Romania". In Jerzy W. Borejsza; Klaus Ziemer (eds.). Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes in Europe: Legacies and Lessons from the Twentieth Century. Berghahn Books. p. 466. ISBN 9781571816412. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ George W. White (1999). "Transylvania: Hungarian, Romanian, or Neither?". In Herb, Guntram Henrik; David H. Kaplan (eds.). Nested Identities: Nationalism, Territory, and Scale. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 275. ISBN 0-8476-8467-9. Retrieved 2021-10-15.

- ^ أ ب "Cluj-Napoca. Istoric" (in الرومانية). Clujonline.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ Brubaker et al. 2006, p.xxi

- ^ Lazarovici et al. 1997, p.39 (3.1 De la Napoca romană la Clujul medieval)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةClujeanul-2007 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUFI-2004 - ^ Bunta, Magda (1970) (in hu), A kolozsvári ötvöscég középkori pecsétje, pp. 151–154, http://mek.oszk.hu/07500/07523/07523.pdf

- ^ Bunbury 1879, p. 516.

- ^ أ ب Lazarovici et al. 1997, pp. 202–03 (6.2 Cluj in the Old and Ancient Epochs)

- ^ Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 17 (2.7 Napoca romană)

- ^ Brubaker et al. 2006, p.89

- ^ Alicu 2003, p.9

- ^ Madgearu, Alexandru (2001). Românii în opera Notarului Anonim. Cluj-Napoca: Centrul de Studii Transilvane, Fundația Culturală Română. ISBN 973-577-249-3.

- ^ أ ب Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 204 (6.3 Medieval Cluj)

- ^ Lugli, Federico; Di Rocco, Giulia; Vazzana, Antonino; Genovese, Filippo; Pinetti, Diego; Cilli, Elisabetta; Carile, Maria Cristina; Silvestrini, Sara; Gabanini, Gaia; Arrighi, Simona; Buti, Laura (2019-09-11). "Enamel peptides reveal the sex of the Late Antique 'Lovers of Modena'". Scientific Reports (in الإنجليزية). 9 (1): 13130. Bibcode:2019NatSR...913130L. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49562-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6739468. PMID 31511583.

- ^ "Buried Couple Found Holding Hands - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 2019-11-28.

- ^ Brubaker et al. 2006, pp.89–90

- ^ أ ب ت Lazarovici et al. 1997, p.38 (3.1 De la Napoca romană la Clujul medieval)

- ^ أ ب Brubaker et al. 2006, pp. 90–1

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 205 (6.3 Medieval Cluj)

- ^ Martâniuc, Cristina. "Probleme actuale ale calității de subiect de drept internațional public contemporan" (PDF) (in الرومانية). CNAA (Republic of Moldova). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

În istoria poporului român, o uniune personală a fost creată în anul 1600 prin unirea politică a celor trei țări Românești – Transilvania, Moldova și Țara Românească – sub un singur domnitor: Mihai Vodă Viteazul (In the history of the Romanian people, a personal union was created in 1600 with the political union of the three Romanian countries – Transylvania, Moldova and Wallachia – under a single ruler: Michael the Brave)

- ^ Ciorănescu, George (1 September 1976). Michael the Brave – Evaluations and Revaluations of the Walachian Prince (PDF). Radio Free Europe Research: RAD Background Report/191. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ "Treaty of Carlowitz". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ أ ب Brubaker et al. 2006, p.91

- ^ Lazarovici et al. 1997, pp.42,44,68 (3.1 De la Napoca romană la Clujul medieval; 4.1 Centru al mișcării naționale)

- ^ أ ب Lazarovici et al. 1997, p.206 (6.4 Cluj in Modern Times)

- ^ von Wurzbach, Constantin (1884). Urban, Karl Freiherr. In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich (Biographical Encyclopedia of the Austrian Empire) (in الألمانية). Vol. 49. Vienna: Kaiserlich-königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. p. 118.

- ^ "Bem's Campaign in Transylvania; Revolutionary Consolidation and Its Contradictions". MEK (Hungarian Electronic Library). Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ Brubaker et al. 2006, p.92

- ^ أ ب Lazarovici et al. 1997, pp.74–5 (6.4 Centru al mișcării naționale)

- ^ أ ب "Relația dintre elite și popor în perioada memorandistă" (PDF) (in الرومانية). Cluj: Centrul de Resurse pentru Diversitate Etnoculturală. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Ambrus Miskolczy (2001). "A modern román nemzet a "régi" Magyarországon" (PDF) (in الهنغارية). Rubicon. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ Georges Castellan (1989). A history of the Romanians. Boulder: East European Monographs. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-88033-154-8.

- ^ أ ب Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 207 (6.4 Cluj in Modern Times)

- ^ Brubaker et al. 2006, p.68

- ^ أ ب Brubaker et al. 2006, pp. 100–1

- ^ Hupchick, Dennis P. (1995). Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 91. ISBN 0-312-12116-4.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Lazarovici et al. 1997, pp. 140–41 (5.2 Dictatul de la Viena – 30 August 1940)

- ^ Sulzberger, C.L. (12 July 1940). "Hungarians' Army Marches into Cluj; Receives a Frenzied Welcome from Magyars in Former Rumanian Territory, but Atmosphere is Tense; Officers of Occupying Troops Charge that 12 Were Slain by Retreating Force". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Peter Kenez (May 2006). Hungary from the Nazis to the Soviets – the establishment of the Communist regime in Hungary, 1944–1948. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85766-X. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. (2001). Lying About Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial. London: Basic Books. p. 95. ISBN 0-465-02153-0.

- ^ "Russians Smash on; Memel Reported Cut Off as New Drive Reaches German Frontier; Szeged, Cluj Seized; Soviet Tanks Cross Tisza, Menacing Budapest; Berlin Admits Russians Smash on Near East Prussia". The New York Times. 12 October 1944. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 213 (6.5 Cluj in Modern Times)

- ^ Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 153 (5.3 Perioada totalitarismului)

- ^ Johanna Granville, "If Hope is Sin, Then We Are All Guilty: Romanian Students' Reactions to the Hungarian Revolution and Soviet Intervention, 1956–1958 Archived 18 سبتمبر 2012 at the Wayback Machine", Carl Beck Paper, no. 1905 (April 2008): 1–78.

- ^ Ludanyi, Andrew (June 2006). "The Impact of 1956 on the Hungarians of Transylvania". Hungarian Studies. Akadémiai Kiadó. 20 (1): 93. doi:10.1556/HStud.20.2006.1.9.

- ^ Kálmán, Aniszi (March 1999). A Bolyai Tudományegyetem utolsó esztendeje: Beszélgetés dr. Sebestyén Kálmánnal. Hitel, XII, No. 3. p. 83.

- ^ A romániai magyar fõiskolai oktatás: Múlt, jelen, jövõ. Cluj/Kolozsvár: Jelenlét Alkotó Társaság. 1990. p. 21.

- ^ Varga, E. Árpád. "Erdély etnikai és felekezeti statisztikája (1850–1992)" [Ethnic and denominational statistics of Transylvania (1850–1992)] (in الهنغارية). Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ أ ب Lazarovici et al. 1997, pp. 154,159 (5.3 Perioada totalitarismului)

- ^ "O mură în gura comisiei "Evenimentele din decembrie"" (in الرومانية). Academia Cațavencu. 30 January 1996. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFinancial Times-2008 - ^ "Guvernul Boc a fost învestit de Parlament". Cotidianul (in الرومانية). 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ^ Bianca Preda (22 June 2012). "Emil Boc a depus jurământul de primar". Adevărul (in الرومانية). Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- ^ "Cluj Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "Air Temperature (monthly and yearly absolute maximum and absolute minimum)" (PDF). Romanian Statistical Yearbook: Geography, Meteorology, and Environment. Romanian National Statistic Institute. 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Pascu 1974, p.102

- ^ أ ب ت ث Pascu 1974, pp.222–3

- ^ Pascu et al. 1957, p.60

- ^ Trócsányi, Zsolt. "History of Transylvania". Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- ^ أ ب Jakab Elek, Kolozsvar Tortenete, II, Okleveltar, Budapesta, 1888, p.750

- ^ Katona Lajos, Kolozsvar terulete es nepessege, in "Kolozsvari Szemle", 1943, no.4, p.294

- ^ Brubaker, Rogers (24 September 2008). "Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town" (PDF). National Program Excellent University. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ^ "Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". National Institute of Statistics. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةvarga-arpad - ^ "Orașe infrățite". Cluj-Napoca City Hall. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ^ "Pesquisa de Legislação Municipal – No 14471". Prefeitura da Cidade de São Paulo [Municipality of the City of São Paulo] (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Lei Municipal de São Paulo 14471 de 2007 WikiSource (البرتغالية)

- ^ Marius Mureșan (13 January 2009). "Municipiul Cluj-Napoca s-a înfrățit cu orașul Valdivia, din Chile" (in Romanian). Napoca News. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

المراجع

- Gh. Lazarovici, D. Alicu, C. Pop, I. Hica, P. Iambor, Șt. Matei, E. Glodaru, I. Ciupea, Gh. Bodea (1997). Cluj-Napoca – Inima Transilvaniei. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Studia. ISBN 973-97555-0-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gheorghe Bodea (2002). Clujul vechi și nou. Cluj-Napoca: ProfImage. ISBN 973-0-02539-8.

- Rogers Brubaker, Margit Feischmidt, Jon Fox & Liana Grancea (2006). "Introduction". Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12834-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bunbury, Edward Herbert (1879). A History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lukács József (2005). Povestea orașului-comoară. Scurtă istorie a Clujului și monumentelor sale. Cluj-Napoca: Apostrof. ISBN 973-9279-74-0.

- Raoul Șorban (2003). Invazie de stafii. Însemnări și mărturisiri despre o altă parte a vieții. Bucharest: Meridiane. ISBN 973-33-0477-8.

- Dorin Alicu (2003). Județul Cluj – trecut și prezent. Cluj-Napoca: ProfImage. ISBN 973-555-090-3.

- Dorin Alicu, Ion Ciupea, Mihai Cojocneanu, Eugenia Glodariu, Ioana Hica, Petre Iambor, Gheorghe Lazărov (1995). Cluj-Napoca, de la începuturi până azi. Cluj-Napoca: Clusium. ISBN 973-7924-05-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cluj-Napoca=Claudiopolis. Bucharest: Noi Media Print. 2004.

- Cluj-Napoca – Ghid. Sedona. 2002.

- Ștefan Pascu, Iosif Pataki, Vasile Popa (1957). Clujul.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ștefan Pascu, Viorica Marica (1969). Clujul medieval. Bucharest: Meridiane.

- Ștefan Pascu (1974). Istoria Clujului. Bucharest.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Aurel Anton, Iuliua Cosma, Vasile Popa, Gheorghe Voișanu (1973). Cluj. Ghid turistic al județului. Bucharest: Editura pentru Turism.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Simon András, Gáll Enikõ, Tonk Sandor, Laszlo Tamas, Maxim Aurelian, Jancsik Peter, Coroiu Teodora (2003). Atlasul localităților județului Cluj. Cluj-Napoca: Suncart.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Cluj-Napoca, orașul comoară al Transilvaniei, România". CLUJonline.com. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- "O istorie inedită a Clujului". ReMARK ltd. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- "Anuarul Institutului de Istorie "George Bariț" din Cluj-Napoca". "George Bariț" History Institute, Cluj-Napoca / Romanian Academy. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

وصلات خارجية

Official websites

- Cluj-Napoca: Official administration site (Romanian)

- Cluj County Prefecture (Romanian)

- Cluj-Napoca Local Civic Council (Romanian)

- CTP (Public Transport Company) official website (Romanian)

- Cluj-Napoca International Airport (إنگليزية) (Romanian)

City guides

- Interactive map, directory and various connected to the city (إنگليزية) (Romanian) (مجرية) (بالعربية) (بالألمانية) (بالإسپانية) {{{1}}}, {{{2}}} (بالفرنسية) (Italian) (هولندية) (بالروسية) (لغة تركية)

- Road map of the access points to Cluj-Napoca

Photos

قالب:Cities in Cluj county قالب:PlacesCluj قالب:Companies in Cluj-Napoca

- CS1 الرومانية-language sources (ro)

- CS1 الهنغارية-language sources (hu)

- Articles with dead external links from July 2017

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Articles containing رومانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing مجرية-language text

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible nickname list

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles containing يديشية-language text

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2011

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Articles with Hungarian-language external links

- كلوج-ناپوكا

- Populated places in Cluj County

- Capitals of the Principality of Transylvania

- مدن رومانيا