إنوسيس

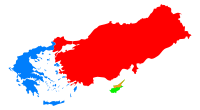

Enosis (باليونانية: Ένωσις, IPA: [ˈenosis], "union") is the movement of various Greek communities that live outside Greece for incorporation of the regions that they inhabit into the Greek state. The idea is related to the Megali Idea, an irredentist concept of a Greek state that dominated Greek politics following the creation of modern Greece in 1830. The Megali Idea called for the annexation of all ethnic Greek lands, parts of which had participated in the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s but were unsuccessful and so remained under foreign rule.

A widely-known example of enosis is the movement within Greek Cypriots for a union of Cyprus with Greece. The idea of enosis in British-ruled Cyprus became associated with the campaign for Cypriot self-determination, especially among the island's Greek Cypriot majority. However, many Turkish Cypriots opposed enosis without taksim, the partitioning of the island between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. In 1960, the Republic of Cyprus was born, resulting in neither enosis nor taksim.

Around then, Cypriot intercommunal violence occurred in response to the different objectives, and the continuing desire for enosis resulted in the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état in an attempt to achieve it. It, however, prompted Turkey into launching the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, which led to partition and the current Cyprus dispute.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

History

The boundaries of the Kingdom of Greece were originally established at the London Conference of 1832[1] following the Greek War of Independence.[2] The Duke of Wellington wanted the new state to be limited to the Peloponnese[3] because Britain wished to preserve as much of the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire as possible. The initial Greek state included little more than the Peloponnese, Attica and the Cyclades. Its population amounted to less than 1 million, with three times as many ethnic Greeks living outside it, mainly in Ottoman territory.[4] Many of them aspired to be incorporated in the kingdom, and movements among them calling for enosis (union) with Greece, often achieved popular support. With the decline of the Ottoman Empire, Greece expanded with a number of territorial gains.

The Ionian Islands had been placed under British protection as a result of the Treaty of Paris in 1815,[5] but once Greek independence had been established after 1830, the islanders began to resent foreign colonial rule and to press for enosis. Britain transferred the islands to Greece in 1864.

Thessaly remained under Ottoman control after the formation of the Kingdom of Greece. Although parts of the territory had participated in the initial uprisings in the Greek War of Independence in 1821, the revolts had been swiftly crushed. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, Greece remained neutral as a result of assurances by the great powers that her territorial claims on the Ottoman Empire would be considered after the war. In 1881, Greece and the Ottoman Empire signed the Convention of Constantinople, which created a new Greco-Turkish border that Incorporated most of Thessaly into Greece.

Crete rebelled against Ottoman rule during the Cretan Revolt of 1866-69 and used the motto "Crete, Enosis, Freedom or Death". The Cretan State was established after the intervention of the Great Powers, and Cretan union with Greece occurred de facto in 1908 and de jure in 1913 by the Treaty of Bucharest.

An unsuccessful Greek uprising in Macedonia against Ottoman rule had taken place during the Greek War of Independence. There was a failed rebellion in 1854 that aimed to unite Macedonia with Greece.[6] The Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 after the Russo-Turkish War awarded nearly all of Macedonia to Bulgaria. That resulted in the 1878 Greek Macedonian rebellion and the reversal of the award at the Treaty of Berlin (1878), leaving the territory in Ottoman hands. Then followed the protracted Macedonian Struggle between Greeks and Bulgarians in the region, the resultant guerrilla war not coming to an end until the revolution of Young Turks in July 1908. Bulgarian and Greek rivalries over Macedonia became part of the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, with the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest awarding Greece large parts of Macedonia, including Thessaloniki. The Treaty of London (1913) awarded southern Epirus to Greece, the Epirus region having rebelled against Ottoman rule during the Epirus Revolt of 1854 and the Epirus Revolt of 1878.

In 1821, several parts of Western Thrace rebelled against Ottoman rule and participated in the Greek War of Independence. During the Balkan Wars, Western Thrace was occupied by Bulgarian troops, and in 1913, Bulgaria gained Western Thrace under the terms of the Treaty of Bucharest. After World War I, Western Thrace was withdrawn from Bulgaria under the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and temporarily managed by the Allies before being it was given to Greece at the San Remo Conference in 1920.

After World War I, Greece began the Occupation of Smyrna and of surrounding areas of Western Anatolia in 1919 at the invitation of the victorious Allies, particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The occupation was given official status in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, with Greece being awarded most of Eastern Thrace and a mandate to govern Smyrna and its hinterland.[7] Smyrna was declared a protectorate in 1922, but the attempted enosis failed since the new Turkish Republic prevailed in the resulting Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, when most Anatolian Christians who had not already fled during the war were forced to relocate to Greece in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

Most of the Dodecanese Islands were slated to become part of the new Greek state in the London Protocol of 1828, but when Greek independence was recognised in the London Protocol of 1830, the islands were left outside the new Kingdom of Greece. They were occupied by Italy in 1912 and held until World War II, when they became a British military protectorate. The islands were formally united with Greece by the 1947 Treaty of Peace with Italy, despite objections from Turkey, which also desired them.

The Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was proclaimed in 1914 by ethnic Greeks in Northern Epirus, the area having been incorporated into Albania after the Balkan Wars. Greece held the area between 1914 and 1916 and unsuccessfully tried to annex it in March 1916,[8] but in 1917 Greek forces were driven from the area by Italy, who took over most of Albania.[9] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece, but Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War made the area revert to Albanian control.[10] Italy's invasion of Greece from the territory of Albania in 1940 and the successful Greek counterattack let the Greek army briefly hold Northern Epirus for a six-month period until the German invasion of Greece in 1941. Tensions between Greece and Albania remained high during the Cold War, but relations began to improve in the 1980s with Greece's abandonment of any territorial claims over Northern Epirus and the lifting of the official state of war between both countries.[8]

In modern times, apart from Cyprus, the call for enosis is most often heard among part of the Greek community living in southern Albania.[11]

Cyprus

سميرنا

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the Ottoman Empire. As part of the Treaty of London (1915), by which Italy left the Triple Alliance (with Germany and Austria-Hungary) and joined France, Great Britain and Russia in the Triple Entente, Italy was promised the Dodecanese and, if the partition of the Ottoman Empire were to occur, land in Anatolia including Antalya and surrounding provinces presumably including Smyrna.[12] But in later 1915, as an inducement to enter the war, British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey in private discussion with Eleftherios Venizelos, the Greek Prime Minister at the time, promised large parts of the Anatolian coast to Greece, including Smyrna.[12] Venizelos resigned from his position shortly after this communication, but when he had formally returned to power in June 1917, Greece entered the war on the side of the Entente.[13]

The evacuation of Smyrna by Greek troops ended most of the large scale fighting in the Greco-Turkish war which was formally ended with an Armistice and a final treaty on 24 July 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne. Much of the Greek population was included in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey resulting in migration to Greece and elsewhere.[14]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "On This Day In History: Independence Of Greece Is Recognized By The Treaty Of London – On May 7, 1832". Ancient Pages. 7 May 2016.

- ^ Anagnostopoulos, Nikodemos (2017). Orthodoxy and Islam: Theology and Muslim–Christian Relations in Modern Greece and Turkey. Routledge. ISBN 9781315297910.

- ^ Cooke, Tim (2010). The New Cultural Atlas of the Greek World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 174. ISBN 9780761478782.

- ^ Hupchick, D (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Springer. p. 223. ISBN 9780312299132.

- ^ Grotke, Kelly L.; Prutsch, Markus Josef, eds. (2014). Constitutionalism, Legitimacy, and Power: Nineteenth-century Experiences. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780198723059.

- ^ Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: prelude to collapse, 1839-1878. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 249–252. ISBN 9783515076876.

- ^ Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe. Vol. 2. p. 888. ISBN 9781576078006.

- ^ أ ب Konidaris, Gerasimos (2005). Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (ed.). The new Albanian migrations. Sussex Academic Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781903900789.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801-1927. Routledge. pp. 543–544. ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3.

- ^ Stein, Jonathan (2000). The politics of national minority participation in post-communist Europe : state-building, democracy, and ethnic mobilization. Armonk, N.Y.: Sharpe. p. 180. ISBN 9780765605283.

- ^ أ ب Jensen, Peter Kincaid (1979). "The Greco-Turkish War, 1920–1922". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 4. 10 (4): 553–565. doi:10.1017/s0020743800051333.

- ^ Finefrock, Michael M. (1980). "Atatürk, Lloyd George and the Megali Idea: Cause and Consequence of the Greek Plan to Seize Constantinople from the Allies, June–August 1922". The Journal of Modern History. 53 (1): 1047–1066. doi:10.1086/242238. S2CID 144330013.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSmith

Sources

- Klapsis, Antonis (2009). "Between the Hammer and the Anvil. The Cyprus Question and the Greek Foreign Policy from the Treaty of Lausanne to the 1931 Revolt". Modern Greek Studies Yearbook. University of Minnesota. 24: 127–140. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Papapolyviou, Petros (1996). Η Κύπρος και οι Βαλκανικοί Πόλεμοι: Συμβολή στην Ιστορία του Κυπριακού Εθελοντισμού [Cyprus and the Balkan Wars: A Contribution to the History of Cypriot Volunteerism]. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Thesis (Doctoral Dissertation) (in اليونانية). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 1–407. doi:10.12681/eadd/8976. hdl:10442/hedi/8976. Retrieved 6 September 2017.