قهوة عربية

دلة هو وعاء قهوة عربي تقليدي يحتوي على أكواب وحبوب قهوة.. | |

| Alternative names | القهوة العربية |

|---|---|

| Type | البن العربي |

| Course | مشروب |

| Place of origin | اليمن |

| Region or state | العالم العربي، الشرق الأوسط |

| Associated cuisine | مطبخ عربي |

| Invented | القرن الخامس عشر |

| Serving temperature | ساخنة |

| |

القهوة العربية هي نسخة من القهوة المخمرة لحبوب القهوة العربية. طورت معظم الدول العربية في جميع أنحاء الشرق الأوسط طرقًا متميزة لـ تخمير وتحضير القهوة. يُضاف الهيل غالبًا هو نوع من التوابل،[1] ولكن يمكن بدلا من ذلك تقديمها ساده أو مع سكر.

هناك عدة أنماط مختلفة لتخمير القهوة حسب تفضيل الشارب. بعض الطرق تحافظ على القهوة خفيفة بينما يمكن للآخرين جعلها دسمة. القهوة العربية مرة، وعادة لا يضاف إليها السكر. وعادة ما يتم تقديمه في فنجان صغير مزين بنمط زخرفي يعرف باسم فنجان. ثقافيًا، يتم تقديم القهوة العربية أثناء التجمعات العائلية أو عند استقبال الضيوف.

القهوة العربية متأصلة في الثقافة والتقاليد الشرق أوسطية والعربية، وهي الشكل الأكثر شعبية من القهوة التي يتم تخميرها في الشرق الأوسط. نشأت في الشرق الأوسط، بدءًا من اليمن وسافرت في النهاية إلى مكة (الحجاز)، ومصر، وبلاد الشام، ثم، في منتصف القرن السادس عشر، إلى تركيا ومن هناك إلى أوروبا حيث أصبحت القهوة في النهاية شائعة أيضًا.[2] القهوة العربية هي تراث ثقافي غير ملموس للدول العربية وأكدته اليونسكو.[3]

أصل الكلمة

دخلت كلمة قهوة إلى اللغة الإنجليزية عام 1582 عبر كلمة "كوفي" الهولندية،[4] مستعارة من التركية العثمانية "kahve"، وهي بدورها مستعارة من العربية قَهْوَة (قهوة، "قهوة، مشروب").[5] ربما كانت كلمة "قهوة" قد أشارت في الأصل إلى شهرة المشروب بأنه مثبط للشهية من كلمة "قهية" (العربية: قَهِيَ).[6][7] لا يستخدم اسم "قهوة" للإشارة إلى التوت أو النبات (منتجات المنطقة)، والمعروفين باللغة العربية باسم "بن". كان للسامية جذر "qhh" "اللون الداكن"، والذي أصبح تسمية طبيعية للمشروبات. وفقًا لهذا التحليل، فإن الشكل الأنثوي "قهوة" (يعني أيضًا "داكن اللون، باهت، جاف، حامض") كان له أيضًا معنى النبيذ، والذي غالبًا ما يكون أيضًا داكن اللون. [8]

التاريخ

يظهر أقرب دليل موثوق به على شرب القهوة أو معرفة شجرة البن على أنه أسطورة راعي الماعز الإثيوبي المسمى كالدي الذي لاحظ تغيرًا في سلوك ماعز عندما أكلوا توت أشجار البن. في البداية، تم مضغ حبوب البن بدلاً من طحنها وتحميصها وتحويلها إلى سائل.[9] يعتقد بعض المؤرخين أن القهوة دخلت إلى شبه الجزيرة العربية حوالي عام 675 بعد الميلاد.[10] من المؤكد أنه بحلول منتصف القرن الخامس عشر، كانت القهوة مستخدمة في أديرة اليمن الصوفية.[2] استخدمها الصوفيون ليبقوا أنفسهم يقظين أثناء الولاءات الليلية. ترجمة لمخطوطة الجزيري[11] يتتبع انتشار القهوة من "العربية السعيدة" (اليمن حاليًا) شمالًا إلى مكة والمدينة، ثم إلى المدن الكبرى في القاهرة، ودمشق وبغداد واسطنبول. في عام 1511، تم حظره بسبب تأثيره المحفز من قبل الأئمة الأرثوذكس المحافظين في محكمة دينية في مكة.[12] ومع ذلك، تم إلغاء هذا الحظر في عام 1524 بأمر من السلطان التركي العثماني سليمان الأول، مع إصدار المفتي العام محمد ابوسود الامادي "فتوى" السماح بتناول القهوة.[13] في القاهرة، مصر، تم فرض حظر مماثل عام 1532، وأقيلت المقاهي والمستودعات التي تحتوي على حبوب البن.[14]

التحضير

Arabic coffee is made from coffee beans roasted very lightly or heavily from 165 إلى 210 °C (329 إلى 410 °F) and cardamom, and is a traditional beverage in Arab culture.[15] Traditionally, it is roasted on the premises (at home or for special occasions), ground, brewed and served in front of guests. It is often served with dates, dried fruit, candied fruit or nuts.[16] Arabic coffee is defined by the method of preparation and flavors, rather than the type of roast beans. Arabic coffee is boiled coffee that is not filtered, made black. Sugar is not typically added, but if so, it can be added during preparation or when serving. It is served in a small delicate cup without handles, called finjān. Sometimes, the coffee is moved to a larger and more beautiful pour pitcher to serve in front of the guests, called Dallah. Often, though, the host prepares coffee in the kitchen and highlights a tray of small cups of coffee.[17] Unlike Turkish coffee, traditional Arabic coffee, with its roots in Bedouin tradition, is usually unsweetened (qahwah saada), but sugar can be added depending on the preference of drinker.[citation needed] However, this coffee is never sweet syrup, but rather strong and bitter.[citation needed] To make up for the bitter flavor, coffee is usually served with something sweet – dates are a traditional accompaniment – and other desserts are often served along with a tray of coffee cups.[16]

شبه الجزيرة العربية

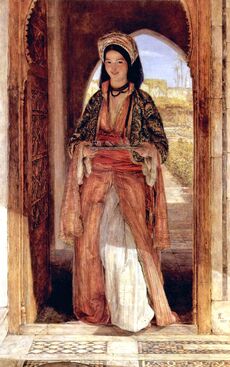

Arabs in the Arabian Peninsula are also creative in the way they prepare coffee. Coffee is different from that in Egypt and Levant in terms of bitterness and the type of cups the coffee is served in. This brewing method is common in Najd and Hejaz, and sometimes other spices like saffron (to give it a golden color), cardamom, cloves, and cinnamon. Arabic coffee in Najd and Hejaz takes a golden color, while in North Arabia a type of Arabic coffee known as qahwah shamālia[18][19] (literally means Northern Coffee) it looks darker in color, because roasting the coffee beans takes a bit longer. Northern coffee is also known as Bedouin coffee in Jordan. Some people add a little-evaporated milk to slightly alter its color; however, this is rare. It is prepared in and served from a special coffee pot called dallah (العربية: دلة); more commonly used is the coffee pot called cezve (also called rikwah or kanaka) and the coffee cups are small with no handle called fenjan. The portions are small, covering just the bottom of the cup. It is served in homes, and in good restaurants by specially clad waiters called gahwaji, and it is almost always accompanied with dates. It is always offered with the compliments of the house.

بلاد الشام

The hot beverage that Palestinians consume is coffee – served in the morning and throughout the day. The coffee of choice is usually Arabic coffee. Arabic coffee is similar to Turkish coffee, but the former is spiced with cardamom and is usually unsweetened.[20] Among Bedouins and most other Arabs throughout the region of Palestine, bitter coffee, known as qahwah sadah (Lit. plain coffee), was a symbol of hospitality. Pouring the drink was ceremonial; it would involve the host or his eldest son moving clockwise among guests – who were judged by age and status – pouring coffee into tiny cups from a brass pot. It was considered "polite" for guests to accept only three cups of coffee and then end their last cup by saying daymen, meaning "always", but intending to mean "may you always have the means to serve coffee".[21]

In Lebanon, the coffee is prepared in a long-handled coffee pot called a "rakwe". The coffee is then poured directly from the "rakwe" into a small cup that is usually adorned with a decorative pattern, known as a finjān.[22] The finjān has a capacity of 60–90 ml (2–3 oz fl). Lebanese coffee is traditionally strong and black and is similar to the coffee of other Middle Eastern countries. However it differs in its beans and roast: the blonde and dark beans are mixed together and it is ground into a very fine powder.[23] It is often joked that a Lebanese person who does not drink coffee is in danger of losing their nationality.[22]

Arabic coffee is much more than just a drink in Jordan – it is a traditional sign of respect and a way to bring people together. Black, cardamom-flavored Arabic coffee, also known as qahwah sādah (welcome coffee), deeply ingrained in Jordanian culture. Providing coffee (and tea) to guests is a large part of the intimate hospitality of the Hashemite Kingdom.

المغرب

While the national drink of Morocco is gunpowder green tea brewed with fresh mint and espresso is very popular, Arabic coffee is also widely consumed, especially on formal occasions. It is often made with the purpose of conducting a business deal and welcoming someone into one's home for the first time, and frequently served at weddings and on important occasions.

الزراعة

يرجع جزء كبير من انتشار القهوة إلى زراعتها في العالم العربي، بدءًا مما يعرف الآن باليمن، على يد رهبان صوفية في القرن الخامس عشر.[24] من خلال آلاف العرب الذين حجوا إلى مكة، انتشر الاستمتاع بالقهوة وحصادها، أو "نبيذ العربي" إلى البلدان العربية الأخرى (مثل مصر، وسوريا) وفي النهاية إلى غالبية العالم خلال القرن السادس عشر. أصبحت القهوة ، بالإضافة إلى كونها أساسية في المنزل، أصبحت جزءًا رئيسيًا من الحياة الاجتماعية.[25] أصبحت المقاهي، قَهوة في اللغة العربية الفصحى الحديثة، "مدارس الحكماء" حيث تطورت إلى أماكن للنقاش الفكري، بالإضافة إلى مراكز الاسترخاء والصداقة.[26]

مقهى

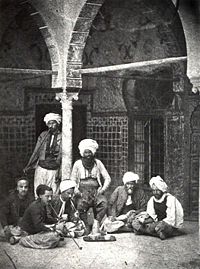

Coffeehouse culture began in the Arab world, and eventually spread to other areas of the world and blended with the local culture.[27] Traditional Arab coffeehouses are places where mostly men meet to socialize over games, coffee, and water pipes (shisha or argille). Depending on where the coffeehouse is, its specialty differs. In Maghreb, green tea is served with mint or coffee is served Arab and/or European style. Arabic coffee, or Turkish coffee, is made in Egypt and the Levant countries. Arabic coffee is a very small amount of dark coffee boiled in a pot and presented in a demitasse cup. Particularly in Egypt, coffee is served mazbuuta, which means the amount of sugar will be "just right", about one teaspoon per cup. However, in the Arabian Peninsula, Arabic coffee is roasted in such a way that the coffee is almost clear. In all of the Arab world, it is traditional for the host to refill the guest's cup until politely signaled that the guest is finished.[25]

Served

Arabic coffee is usually served just a few centiliters at a time.[15] The guest drinks it and if he wishes, he will gesture to the waiter not to pour any more. Otherwise, the host/waiter will continue to serve another few centilitres at a time until the guest indicates he has had enough. The most common practice is to drink only one cup since serving coffee serves as a ceremonial act of kindness and hospitality. Sometimes people also drink larger volumes during conversations.[28]

الجمارك

عادة ما يتم ملء الكؤوس بشكل جزئي فقط، والعرف هو شرب ثلاثة أكواب.[29] تحتل القهوة العربية مكانة بارزة في أعياد العرب التقليدية والمناسبات الخاصة مثل رمضان و العيد.

قراءة الطالع

قراءة القهوة العربية (العربية: قراءة الفنجان) تشبه قراءة أوراق الشاي؛ يُطلب من العميل تناول قهوة عربية طازجة قوية مع ترك حوالي ملعقة صغيرة من السائل في الكوب. ثم يتم قلب الكوب على صحن للسماح للسائل المتبقي بالتجفيف والتجفيف. سيقوم القارئ بعد ذلك بتفسير الأنماط التي تشكلها البقايا السميكة الموجودة داخل الكوب بحثًا عن الرموز والحروف.[30]

Funeral

Arabic funerals gather families and extended relatives, who drink bitter and unsweetened coffee and restore the life and characteristics of the deceased. The men and women gather separately, and it has become very fashionable to employ very presentable women whose only job is to serve coffee all day to the women. Male waiters serve the men. Arab Muslims and Christians share this tradition.[31]

حقائق غذائية

فنجان صغير من القهوة العربية يكاد لا يحتوي على سعرات حرارية أو دهون. يحتوي على كمية قليلة من البروتين.[32][33]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Ingredients Arabic Coffee". Archived from the original on 2018-12-28. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ أ ب Weinberg, Bennett Alan; Bealer, Bonnie K. (2001). The world of caffeine. Routledge. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9.

coffee goat ethiopia Kaldi.

- ^ "Arabic coffee, a symbol of generosity - intangible heritage - Culture Sector - UNESCO". www.unesco.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- ^ OED, s.v. "Coffee".

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "coffee, n." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1891.

- ^ Kaye, Alan (1986). "The Etymology of Coffee: The Dark Brew". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 106 (3): 557–558. doi:10.2307/602112. JSTOR 602112.

- ^ قهي. الباحث العربي. Retrieved September 25, 2011.(see also qahiya: Hans Wehr's Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic. page 930.)

- ^ Kaye, Alan S. (1986). "The etymology of "coffee": The dark brew". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 106 (3): 557–558. doi:10.2307/602112. JSTOR 602112.

- ^ "The history of coffee". National Coffee Association of the United States. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ Empire of the Islamic World. Chelsea House. 2009. p. 14. ISBN 9781604131611.

- ^ Al-Jaziri's manuscript work is of considerable interest with regards to the history of coffee in Europe as well. A copy reached the French royal library, where it was translated in part by Antoine Galland as De l'origine et du progrès du café.

- ^ "resource for Arabic books". www.alwaraq.net.

- ^ Schneider, Irene (2001). "Ebussuud". In Michael Stolleis (ed.). Juristen: ein biographisches Lexikon; von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert (in الألمانية) (2nd ed.). München: Beck. p. 193. ISBN 3-406-45957-9.

- ^ J. E. Hanauer (1907). "About Coffee". Folk-lore of the Holy Land. pp. 291 f.

[All] the coffee-houses [were] closed, and their keepers pelted with the sherds of their pots and cups. This was in 1524, but by an order of Selìm I., the decrees of the learned were reversed, the disturbances in Egypt quieted, the drinking of coffee declared perfectly orthodox

- ^ أ ب "What makes Arabic coffee unique?". Your Middle East. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ أ ب "Gulf Arabic coffee - qahwa arabiyyah". www.dlc.fi. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ "How To Make Arabic Coffee". Terrace Restaurant & Lounge (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2015-03-01. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ Al Asfour, Saud. "القهوة الكويتية.. أصالة وعراقة". Alqabas.

- ^ Al Asfour, Saud. "القهوجي.. "صَبَّاب القهوة" في الكويت قديماً". Alqabas.

- ^ The rich flavors of Palestine Archived 2009-04-16 at the Wayback Machine Farsakh, Mai M. Institute for Middle East Understanding (IMEU), (Originally published by This Week in Palestine) 2006-06-21 Accessed on 2007-12-18

- ^ A Taste of Palestine: Menus and Memories (1993). Aziz Shihab. Corona Publishing Co. p.5 ISBN 978-0-931722-93-6

- ^ أ ب "Food Heritage Foundation – Lebanese coffee". food-heritage.org (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 27 October 2014. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ "Lebanese Coffee, Coffee passion". maatouk.com. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ Civitello, Linda (2007). Cuisine and Culture: A History of Food and People. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. ISBN 9780471741725.

- ^ أ ب Brustad, Kristen; Al-Batal, Mahmoud; Al-Tonsi, Abbas (2010). Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds. Georgetown University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9781589016330.

- ^ "The History Of Coffee". ncausa.org. National Coffee Association of the U.S.A. October 24, 2016.

- ^ S., Hattox, Ralph (2014-01-01). Coffee and Coffeehouses The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295805498. OCLC 934667227.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Arabic Coffee Service | GWNunn.com". gwnunn.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ "Arabic Coffee - A Welcoming Ritual". Cabin Crew Excellence (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on 2015-08-17. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ "Jane - Fortune Teller | Middlesex| South East| UK - Contraband Events". Contraband Events.

- ^ IMEU. "Palestinian Social Customs and Traditions | IMEU". imeu.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ Cherney, Kristeen. "Arabic Coffee Nutrition Information". LIVESTRONG.COM (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ Tulsani, Manoj (2013-05-29). "5 Interesting Facts About Arabic Coffee". Travel Tips and Experience - Rayna Tours and Travels (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2017-04-14.

قراءات إضافية

- Basan, Ghillie (2007). Middle Eastern Kitchen. Hippocrene Books. p. 37. ISBN 978-0781811903.

- Young, Daniel (2009). Coffee Love: 50 Ways to Drink Your Java. John Wiley & Sons. p. 44. ISBN 978-0470289372.

- CS1 uses العربية-language script (ar)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2020

- اختراعات عربية

- إعداد القهوة

- ثقافة عربية

- مطبخ أردني

- مطبخ سعودي

- مطبخ سوري

- مطبخ شامي

- مطبخ عراقي

- مطبخ عربي

- مطبخ عماني

- مطبخ فلسطيني

- مطبخ قطري

- مطبخ كويتي

- مطبخ لبناني

- مطبخ يمني

- منبهات