تاريخ رواندا

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| تاريخ رواندا |

|---|

|

| مملكة رواندا (القرن 11-1962) |

| شرق أفريقيا الألماني (1885–1919) |

| الانتداب البلجيكي (1922-1962) |

| جمهورية رواندا |

| الحرب الأهلية الرواندية (1990-1994) |

| التطهير العرقي الرواندي (1994) |

| حرب الكونغو الأولى (1996-1997) |

| حرب الكونغو الثانية (1998-2003) |

ينقسم سكان رواندا الذين يتجاوز عددهم 7 ملايين نسمة إلى ثلاث فئات عرقية: الهوتو (الذين يؤلفون ما يقرب من 85 في المائة من عدد السكان) والتوتسي (14 في المائة) والتوا (1 في المائة).

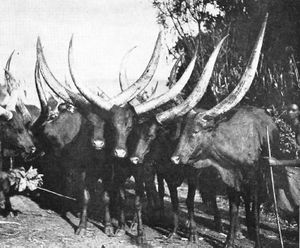

وقبل فترة الاستعمار، كان أبناء التوتسي يشغلون الطبقات العليا في النظام الاجتماعي وأبناء الهوتو الطبقات الدنيا. غير أن الحراك الاجتماعي كان ممكناً، فالهوتو الذي يقتني عدداً كبيراً من الماشية أو غير ذلك من المال كان يمكن استيعابه في طائفة التوتسي كما أن فقراء التوتسي كانوا ينظر إليهم على أنهم من طائفة الهوتو. كذلك كان يوجد نظام عشائري عامل، تعرف فيه عشيرة التوتسي باسم ناينگينيا أو أقوى الأقوياء. وقد عمل الناينگينيا طوال القرن التاسع عشر على توسيع نطاق نفوذهم عن طريق الغزو وبتوفير الحماية في مقابل جزية تدفع.

العصر الحجري الحديث إلى العصور الوسطى

العصور الوسطى

The Twa (" pygmies "), which today still contain tens of thousands of people, were probably the earliest inhabitants of Rwanda. But almost nothing is known about their history. From the 15th century onwards, the kingdom of Rwanda existed in the area of later Rwanda.

تباين الهوتو-التوتسي

In the earlier perception of the Europeans , the people of the Hutu, the mass of the inhabitants, the Tutsi (in the formerly called Watussi warriors ) had immigrated between the 14th century and the 15th century and had subjected the Hutu as a warlike people. The Tutsi were a people with a nilotOrigin. As a minority, they had placed state and military power, while the Hutu had worked as peasants. Even in pre-colonial times, Hutu's uprising against the Tutsi minority, who had been hated by them, had always come under pressure and exploited. This theory was favored by the racist ideas of the colonialists of the early twentieth century.

In fact, the two societies of the peasant Hutu and the cattle-breeding Tutsi were more likely to have a side-by-side relationship. In the case of occasional land conflicts, the Tutsi were superior to the Hutu, but there were hardly any points of contact between them.

Today's science respects the many genetic and cultural similarities between Hutu and Tutsi. Many scientists now believe that the differences were greatly exaggerated and are largely culturally constructed. They point out that both groups inhabit the same area, speak the same language, marry one another, and share cultural characteristics. Differences between both groups are more defined by occupation and social status and not by ethnicity. Nevertheless, one can assume that even before the colonial period there were social opposites between the two populations, which led to conflicts. These were reinforced by the colonial legislation, but not caused. [1]

In general, the Tutsi were the elite of the country, and there were numerous cases of individuals or families who changed their group, which shows that Hutu and Tutsi tend to be two different estates or classes (no boxes, for weddings Were frequent), not tribes or ethnic groups, as is usually represented by colonial literature, various reference works, and media.

الفترة الاستعمارية

على العكس من باقي أفريقيا، فإن رواندا ومنطقة البحيرات العظمى لم يبت فيهما مؤتمر برلين في 1884. وبدلاً من ذلك فقد قـُسـِّمت المنطقة في مؤتمر 1890 في بروكسل. فأُعطِيت رواندا وبوروندي للامبراطورية الألمانية كدوائر مصالح استعمارية في مقابل تنازل ألمانيا عن كل مطالباتها في أوغندا. الخرائط غير الدقيقة التي استخدمتها تلك الاتفاقيات تركت بلجيكا بمطالبة في النصف الغربي من البلد؛ وبعد عدد من المناوشات الحدودية، لم يستقر ترسيم حدود المستعمرة حتى 1900. هذه الحدود ضمت مملكة رواندا وكذلك مجموعة من الممالك الأصغر على ساحل بحيرة ڤكتوريا.

في 1894 ورث روتاريندوا المملكة عن والده روابوگيري الرابع، إلا أن العديد من أعضاء مجلس الملك لم يكونوا سعداء. ونشب تمرد وقـُتِلت العائلة. ورث يوهي موسينگا العرش عن طريق أمه وخيلانه، إلا أن المعارضة ظلت باقية.

شرق أفريقيا الألماني (1885–1919)

The first German to visit or explore Rwanda was Count Gustav Adolf von Götzen, who from 1893 to 1894 led an expedition to claim the hinterlands of the Tanganyika colony. Götzen entered Rwanda at Rusumo Falls, and then travelled through Rwanda, meeting the mwami (king) at his palace in Nyanza, and eventually reached Lake Kivu, the western edge of the kingdom. With only 2,500 soldiers in East Africa, Germany hardly changed the social structures in much of the region, especially in Rwanda.[بحاجة لمصدر]

War and division seemed to open the door for colonialism, and in 1897 German colonialists and missionaries arrived in Rwanda. The Rwandans were divided; a portion of the royal court was wary and the other thought the Germans might be a good alternative to dominance by Buganda or the Belgians[بحاجة لمصدر]. Backing their faction in the country a pliant government was soon in place. Rwanda put up less resistance than Burundi did to German rule.

In the early years the Germans had little direct control in the region and completely relied on the indigenous government. The Germans did not encourage modernization and centralization of the regime.; however, they did introduce the collection of cash taxes. The Germans hoped cash taxes, rather than taxes in kind, would force farmers to switch to profitable crops, like coffee, in order to acquire the required cash to pay taxes. This policy led to changes in the Rwandan economy.

During this period, increasing numbers accepted race. German officials and colonists in Rwanda incorporated these theories into their native policies. The Germans believed the Tutsi ruling class was racially superior to the other native peoples of Rwanda because of their alleged "Hamitic" origins on the Horn of Africa, which they believed made them more "European" than the Hutu. The colonists, including powerful Roman Catholic officials, favored the Tutsis because of their taller stature, more "honorable and eloquent" personalities, and willingness to convert to Roman Catholicism, the colonist. The Germans favored Tutsi dominance over the farming Hutus (almost in a feudalistic manner) and granted them basic ruling position. These positions eventually turned into the overall governing body of Rwanda[مطلوب توضيح].[بحاجة لمصدر] [مطلوب توضيح]

Prior to the colonial period the Tutsis comprised about 15-16% of the population. While many Tutsis were poor peasants[بحاجة لمصدر], they comprised the majority of the ruling elite and monarchy were Tutsi. A significant minority of the remaining non-Tutsis political elite were Hutu.

The German presence had mixed effects on the authority the Rwandan governing powers. The Germans helped the Mwami increase their control over Rwandan affairs. But Tutsi power weakened with the introduction of capitalist forces and through increased integration with outside markets and economies. Money came to be seen by many Hutus as a replacement for cattle, in terms of both economic prosperity and for purposes of creating social standing. Another way in which Tutsi power was weakened by Germany was through the introduction of the head-tax on all Rwandans. As some Tutsis had feared, the tax also made the Hutus feel less bonded to their Tutsi patrons and more dependent on the European foreigners. A head-tax implied equality among those being counted. Despite Germany's attempt to uphold traditional Tutsi domination of the Hutus, the Hutu began to shift their ideas.

By 1899 the Germans placed advisors at the courts of local chiefs. The Germans were preoccupied with fighting uprisings in Tanganyika, especially the Maji Maji war of 1905-1907. On May 14, 1910 the European Convention of Brussels fixed the borders of Uganda, Congo, and German East Africa, which included Tanganyika and Ruanda-Urundi.[1] In 1911, the Germans helped the Tutsi put down a rebellion of Hutu in the northern part of Rwanda who did not wish to submit to central Tutsi control.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الانتداب البلجيكي من عصبة الأمم (1922-1945)

عند نهاية الحرب العالمية الأولى، قبلت بلجيكا انتداب عصبة الأمم سنة 1916 لحكم رواندا كإقليم رواندا-اوروندي, along with its existing Congo colony to the west. The portion of the German territory, never a part of the Kingdom of Rwanda, was stripped from the colony and attached to تنگانيقا، which had been mandated to the British.[بحاجة لمصدر] A colonial military campaign from 1923 to 1925 brought the small independent kingdoms to the west, such as كينگوگو، بوشيرو، بوكونزي و بوسوزو, under the power of the central Rwandan court.[2]

The Belgian government continued to rely on the Tutsi power structure for administering the country, although they became more directly involved in extended its interests into education and agricultural supervision. The Belgians introduced cassava, maize and the Irish potato, to try to improve food production for subsistence farmers. This was especially important in the face of two droughts and subsequent famines in 1928-29 and in 1943-44. In the second, known as the Ruzagayura famine, one-fifth to one-third of the population died. In addition, many Rwandans migrated to neighboring Congo, adding to later instability there.[3]

The Belgians intended the colony to be profitable. They introduced coffee as a commodity crop and used a system of forced labor to have it cultivated. Each peasant was required to devote a certain percentage of their fields to coffee and this was enforced by the Belgians and their local, mainly Tutsi, allies. A system of corvée that had existed under Mwami Rwabugiri was used. This forced labour approach to colonization was condemned by many internationally, and was extremely unpopular in Rwanda. Hundreds of thousands of Rwandans immigrated to the British protectorate of Uganda, which was much wealthier and did not have the same policies.

Belgian rule reinforced an ethnic divide between the Tutsi and Hutu, and they supported Tutsis political power. Due to the eugenics movement in Europe and the United States, the colonial government became concerned with the differences between Hutu and Tutsi. Scientists arrived to measure skull—and thus, they believed, brain—size. Tutsi's skulls were bigger, they were taller, and their skin was lighter. As a result of this, Europeans came to believe that Tutsis had Caucasian ancestry, and were thus "superior" to Hutus. Each citizen was issued a racial identification card, which defined one as legally Hutu or Tutsi. The Belgians gave the majority of political control to the Tutsis. Tutsis began to believe the myth of their superior racial status, and exploited their power over the Hutu majority. In the 1920s, Belgian ethnologists analysed (measured skulls, etc.) thousands of Rwandans on analogous racial criteria, such as which would be used later by the Nazis. In 1931, an ethnic identity was officially mandated and administrative documents systematically detailed each person's "ethnicity,". Each Rwandan had an ethnic identity card.[4]

A history of Rwanda that justified the existence of these racial distinctions was written. No historical, archaeological, or above all linguistic traces have been found to date that confirm this official history. The observed differences between the Tutsis and the Hutus are about the same as those evident between the different French social classes in the 1950s. The way people nourished themselves explains a large part of the differences: the Tutsis, since they raised cattle, traditionally drank more milk than the Hutu, who were farmers.

The fragmenting of Hutu lands angered Mwami Yuhi IV, who had hoped to further centralize his power enough to get rid of the Belgians. In 1931 Tutsi plots against the Belgian administration resulted in the Belgians' deposing the Tutsi Mwami Yuhi. The Tutsis took up arms against the Belgians, but feared the Belgians' military superiority and did not openly revolt.[5] Yuhi was replaced by Mutara III, his son. In 1943, he became the first Mwami to convert to Catholicism.[بحاجة لمصدر]

From 1935 on, "Tutsi", "Hutu" and "Twa" were indicated on identity cards. However, because of the existence of many wealthy Hutu who shared the financial (if not physical) stature of the Tutsi, the Belgians used an expedient method of classification based on the number of cattle a person owned. Anyone with ten or more cattle was considered a member of the Tutsi class. The Roman Catholic Church, the primary educators in the country, subscribed to and reinforced the differences between Hutu and Tutsi. They developed separate educational systems for each[بحاجة لمصدر], although throughout the 1940s and 1950s the vast majority of students were Tutsi.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الوصاية البلجيكية من الأمم المتحدة (1945-1961)

Following World War II, Ruanda-Urundi became a United Nations trust territory with Belgium as the administrative authority. Reforms instituted by the Belgians in the 1950s encouraged the growth of democratic political institutions but were resisted by the Tutsi traditionalists, who saw them as a threat to Tutsi rule.

From the late 1940s, King Rudahigwa, a Tutsi with democratic vision, abolished the "ubuhake" system and redistributed cattle and land. Although the majority of pasture lands remained under Tutsi control, the Hutu began to feel more liberation from Tutsi rule. Through the reforms, the Tutsis were no longer perceived to be in total control of cattle, the long-standing measure of a person's wealth and social position. The reforms contributed to ethnic tensions.

The Belgian institution of ethnic identity cards contributed to the growth of group identities. Belgium introduced electoral representation for Rwandans, by means of secret ballot. The majority Hutus made enormous gains within the country. The Catholic Church, too, began to oppose Tutsi mistreatment of Hutus, and began promoting equality.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Mwami Mutara took steps to end the destabilization and chaos he saw in the land.[بحاجة لمصدر] Mutara made many changes; in 1954 he shared out the land between the Hutu and the Tutsi, and agreed to abolish the system of indentured servitude (ubuhake and uburetwa) the Tutsis had practised over the Hutu until then.[بحاجة لمصدر]

النضال يؤدي إلى الاستقلال

In the 1950s and early 1960s, a wave of Pan-Africanism swept through Central Africa, expressed by leaders such as Julius Nyerere in Tanzania and Patrice Lumumba in the Congo. Anti-colonial sentiment rose throughout central Africa, and a socialist platform of African unity and equality for all Africans was promoted. Nyerere wrote about the elitism of educational systems.[6]

Encouraged by the Pan-Africanists,[بحاجة لمصدر] Hutu advocates in the Catholic Church, and by Christian Belgians (who were increasingly influential in the Congo), Hutu resentment of the Tutsi increased. The United Nations mandates, the Tutsi elite class, and the Belgian colonialists added to the growing unrest. Grégoire Kayibanda, founder of PARMEHUTU, led the Hutu "emancipation" movement. In 1957, he wrote the "Hutu Manifesto". His party quickly became militarized. In reaction, in 1959 the Tutsi formed the UNAR party, lobbying for immediate independence for Ruanda-Urundi, to be based on the existing Tutsi monarchy. This group also became militarized. Skirmishes began بين جماعتي أونار UNAR و پارمىهوتو PARMEHUTU. وفي يوليو 1959، حين توفي موامي (الملك) التوتسي موتارا الثالث شارل إثر تطعيم اعتيادي، ظن بعض التوتسي أنه أغتيل. أخوه الأصغر غير الشقيق أصبح العاهل التوتسي التالي، موامي (الملك) كيگلي الخامس.

وفي نوفمبر 1959، Tutsis[بحاجة لمصدر] tried to assassinate Kayibanda. Rumors of the death of Hutu politician Dominique Mbonyumutwa at the hands of Tutsis, who had beaten him, set off a violent retaliation, called the wind of destruction. Hutus killed an estimated 20,000 to 100,000 Tutsi; thousands more, including the Mwami, fled to neighboring Uganda before Belgian commandos arrived to quell the violence. Tutsi leaders accused the Belgians of abetting the Hutus. A UN special commission reported racism reminiscent of "Nazism" against the Tutsi minorities, and discriminatory actions by the government and Belgian authorities.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The revolution of 1959 marked a major change in political life in Rwanda. Some 150,000 Tutsis were exiled to neighbouring countries. Tutsis who remained in Rwanda were excluded from political power in a state becoming more centralized under Hutu power. Tutsi refugees also fled to the South Kivu province of the Congo, where they were known as Banyamalenge.

In 1960, the Belgian government agreed to hold democratic municipal elections في رواندا-أوروندي. The Hutu majority elected Hutu representatives. Such changes ended the Tutsi monarchy, which had existed for centuries. A Belgian effort to create an independent Ruanda-Urundi with Tutsi-Hutu power sharing failed, largely due to escalating violence. At the urging of the UN, the Belgian government divided رواندا-أوروندي into two separate countries, رواندا وبوروندي.

بدء الصراع العرقي

فقدت ألمانيا، السلطة الاستعمارية السابقة، سيطرتها على رواندا خلال الحرب العالمية الأولى ثم وضع الإقليم تحت الإدارة البلجيكية. وفي أواخر الخمسينيات، في أثناء موجة إنهاء الاستعمار الكبيرة، زادت حالات التوتر في رواندا. وكانت حركة الهوتو السياسية، التي يمثل حكم الأغلبية مكسباً لها، تكتسب الزخم بينما قاومت بعض شرائح من مؤسسة التوتسي عملية التحول الديمقراطي وفقدان مزاياها المكتسبة. وفي نوفمبر 1959، أشعل أحد أحداث العنف نيران ثورة للهوتو تم فيها قتل المئات من التوتسي وتشريد الآلاف وإجبارهم على الفرار إلى البلدان المجاورة. وكات تلك بداية ما يطلق عليه "ثورة فلاحي الهوتو" أو "الثورة الاجتماعية" التي استمرت من 1959 إلى 1961، وآذنت بنهاية سيطرة التوتسي وشحذ نصال التوتر العرقي. وبحلول عام 1962، وعند حصول رواندا على استقلالها، كان 000 120 شخص، معظمهم من أبناء طائفة التوتسي، قد لجأوا إلى إحدى دول الجوار هرباً من العنف الذي صاحب مجيء طائفة الهوتو التدريجي إلى السلطة.

واستمرت حلقة جديدة من الصراع والعنف الطائفي بعد الاستقلال. وبدأ اللاجئون من التوتسي في تنزانيا وزائير الساعين لاسترداد مواقعهم السابقة في رواندا ينظمون أنفسهم ويشنون الهجمات على أهداف للهوتو وعلى حكومة الهوتو. ووقعت عشرة هجمات من هذا القبيل في الفترة بين 1962 و1967، كل منها يؤدي إلى عمليات قتل انتقامية لأعداد كبيرة من التوتسي المدنيين في رواندا خلّفت موجات جديدة من اللاجئين. وبحلول أواخر الثمانينيات كان نحو 000 480 من الروانديين قد تحولوا إلى لاجئين، بصفة رئيسية في بوروندي وأوغندا وزائير وتنزانيا. واستمروا في المناداة بإعمال حقهم القانوني الدولي في العودة إلى رواندا، غير أن جوفنال هابياريمانا، رئيس رواندا آنذاك، اتخذ موقفاً يتمثل في أن زيادة الضغوط السكانية وقلة الفرص الاقتصادية المتوفرة لا يسمحان باستيعاب أعداد كبيرة من لاجئي التوتسي.

الحرب الأهلية

مقالة مفصلة: الحرب الأهلية الرواندية

مقالة مفصلة: الحرب الأهلية الرواندية

وفي عام 1988، أنشئت الجبهة الوطنية الرواندية في كمبالا، بأوغندا، بوصفها حركة سياسية وعسكرية ذات أهداف معلنة تتمثل في تأمين عودة الروانديين المنفيين إلى الوطن وإعادة تشكيل الحكومة الرواندية، بما في ذلك تقاسم السلطة السياسية. وتألفت الجبهة الوطنية الرواندية بصفة رئيسية من التوتسي المنفيين في أوغندا، الذين سبق للكثيرين منهم أن خدموا في جيش المقاومة الوطنية التابع للرئيس يوري موسيفيني، الذي أسقط الحكومة الأوغندية السابقة في عام 1986. ومع أن صفوف الجبهة ضمت بعض الهوتو بالفعل، فإن غالبيتها، خاصة من يشغلون المناصب القيادية فيها، كانوا من اللاجئين التوتسي.

وفي 1 أكتوبر 1990، شنت الجبهة هجوماً كبيراً على رواندا من أوغندا بقوة تضم 000 7 مقاتل. وبسبب هجمات الجبهة التي شردت الآلاف، وبفعل لجوء الحكومة إلى سياسة دعائية استهدافية عامدة، جرى وصم جميع أبناء التوتسي داخل البلد بأنهم شركاء للجبهة، ووصم جميع الهوتو الأعضاء في أحزاب المعارضة بأنهم خونة. واستمرت وسائل الإعلام، وبخاصة الإذاعة، في نشر إشاعات لا أساس لها من الصحة، مما أدى لتفاقم المشاكل العرقية.

وفي أغسطس 1993، ومن خلال جهود تحقيق السلام التي قامت بها منظمة الوحدة الأفريقية وحكومات المنطقة، بدا وكأن التوقيع على اتفاقات السلام في أروشا قد وضع حداً للصراع بين الحكومة، التي كانت في قبضة الهوتو آنذاك، والجبهة الوطنية الرواندية المعارضة. وفي تشرين الأول/أكتوبر 1993، أنشأ مجلس الأمن بعثة الأمم المتحدة لتقديم المساعدة إلى رواندا وأنيطت بها ولاية تشمل حفظ السلام وتقديم المساعدات الإنسانية والدعم العام لعملية السلام.

غير أن إرادة تحقيق السلام والمحافظة عليه تعرضت منذ البداية للتخريب من قِبل بعض الأحزاب السياسية الرواندية المشتركة في الاتفاق. وبتعرض بعض جوانب الاتفاق للتأخير في التنفيذ بعد ذلك، أصبحت انتهاكات حقوق الإنسان أكثر انتشاراً وتدهورت الحالة الأمنية. وفيما بعد، بينت الأدلة بما لا يدع مجالاً للشك أن عناصر متطرفة من طائفة الهوتو التي تشكل الأغلبية كانت خلال محادثات السلام في واقع الأمر تخطط لشن حملة إبادة للتوتسي والهوتو المعتدلين.

الإبادة العرقية الرواندية

في 6 نيسان/أبريل 1994، أشعل مصرع رئيسي بوروندي ورواندا في حادث سقوط طائرة على إثر هجوم صاروخي جذوة عدة أسابيع من المذابح الكثيفة والمنهجية. وصدمت عمليات القتل، حيث يقدر أن عدداً يناهز 1 مليون نسمة فقدوا أرواحهم فيها، مشاعر المجتمع الدولي وكان من الواضح أنها أعمال إبادة جماعية. وأشارت التقديرات أيضاً إلى اغتصاب ما بين 000 150 و 000 250 امرأة . وشرع أعضاء الحرس الجمهوري في قتل المدنيين التوتسي في قسم من كيغالي يقع قريباً من المطار. وفي غضون أقل من نصف ساعة من وقوع حادث سقوط الطائرة، كانت المتاريس التي يقف عندها أفراد مليشيات الهوتو ويساعدهم فيها في كثير من الأحيان أفراد من الشرطة شبه العسكرية أو عسكريون قد أقيمت للتحقق من هوية أبناء طائفة التوتسي.

وفي 7 أبريل، بثت محطة الإذاعة والتليفزيون ’الحرة للتلال الألف‘ إذاعة تنسب فيها سقوط الطائرة إلى الجبهة الوطنية الرواندية ووحدة من جنود الأمم المتحدة، وبعض الأقوال التي تحرّض على استئصال "الصرصار التوتسي". وفي وقت لاحق من ذلك اليوم، تم قتل رئيسة الوزراء أجاثا أويلينغييمانا و 10 من أفراد حفظ السلام البلجيكيين المخصصين لحمايتها بطريقة بشعة على أيدي الجنود الحكوميين الروانديين في هجوم على بيتها. وجرى بالمثل اغتيال غيرها من زعماء الهوتو المعتدلين. وسحبت بلجيكا بقية أفراد قوتها بعد المذبحة التي حدثت لجنودها. وفي 21 نيسان/أبريل، طلبت البلدان الأخرى سـحب جنودها، وانخفضت قـوة بعثـة تقديم المساعدة إلى رواندا من 165 2 فرداً في بدايتها إلى 270 فرداً.

وإذا كانت إحدى المشاكل تتمثل في عدم وجود التزام صارم بالمصالحة لدى بعض الأطراف الرواندية، فقد أدى تردد المجتمع الدولي في الرد إلى تفاقم المأساة. وكانت قدرة الأمم المتحدة على الحد من المعاناة البشرية في رواندا مقيدة تقييداً شديداً لعدم استعداد الدول الأعضاء للاستجابة لتغير الظروف في رواندا بتعزيز ولاية البعثة والإسهام بقوات إضافية.

وفي 22 حزيران/يونيه، أذن مجلس الأمن لقوات تحت قيادة فرنسية بالقيام بمهمة إنسانية. وأنقذت هذه المهمة، التي يطلق عليها عملية توركواز حياة مئات المدنيين في جنوب شرق رواندا، ولكن يقال أيضاً إنها سمحت للجنود والمسؤولين والمليشيات الضالعين في جريمة القتل الجماعي بالهروب من رواندا من خلال المناطق الخاضعة لسيطرتها. واستمرت جرائم القتل في المناطق الأخرى حتى 4 تموز/يوليه 1994 حين سيطرت الجبهة الوطنية الرواندية عسكرياً على أراضي رواندا بأكملها.

في أعقاب الإبادة الجماعية

لاذ المسؤولون الحكوميون والجنود والمليشيات الذي شاركوا في جريمة الإبادة الجماعية بالفرار إلى جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، ثم إلى زمبابوي، آخذين معهم 1.4 مليوناً من المدنيين، أغلبهم من الهوتو الذين أبلغوا بأن الجبهة الوطنية الرواندية سوف تقتلهم. وقضى الآلاف نحبهم من الأمراض المنقولة بالمياه. واستخدمت المخيمات أيضاً من قِبل جنود الحكومة الرواندية السابقة لإعادة تسليح وتنظيم عمليات لغزو رواندا. وكانت تلك الهجمات أحد العوامل التي أدت إلى نشوب الحرب بين رواندا وجمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية في عام 1996. وظلت القوات الرواندية السابقة تعمل في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية إلى جانب بعض المليشيات الكونغولية والجماعات المسلحة الأخرى. وهي لا تزال تستهدف السكان المدنيين وتسبب الموت والأذى والضرر.

وبدأت الحكومة الرواندية في نهاية عام 1996 في إجراء المحاكمات التي طال انتظارها على جريمة الإبادة الجماعية. وكان هذا التأخير يرجع إلى أن البلد قد فقد معظم أفراده العاملين في القضاء، ناهيك عن تدمير المحاكم والسجون وغير ذلك من الهياكل الأساسية. وبحلول عام 2000، كان ثمة 000 100 مشتبه في ارتكابهم جريمة الإبادة الجماعية ينتظرون المحاكمة. وفي 2001، بدأت الحكومة في تنفيذ نظام العدالة التشاركية، المعروف باسم غاتشاتشا، للتصدي للكم الهائل من القضايا المتأخرة. وانتخبت المجتمعات المحلية قضاة لإجراء المحاكمات للمشتبه فيهم بجريمة الإبادة الجماعية المتهمين على جميع الجرائم فيما عدا التخطيط للإبادة الجماعية أو الاغتصاب. وأطلق سراح المتهمين في محاكم غاتشاتشا مؤقتا رهن المحاكمة. وسببت عمليات الإفراج قدراً كبيراً من الاستياء بين صفوف الناجين الذين يرون فيها شكلاً من أشكال العفو العام. ولا تزال رواندا تستخدم النظام القضائي الوطني لمحاكمة المتورطين في التخطيط لجريمة الإبادة الجماعية أو الاغتصاب في ظل قانون العقوبات العادي. ولكن هذه المحاكم لا تسمح بالإفراج المؤقت عن المتهمين في جرائم الإبادة الجماعية.

وتخفف محاكم گاتشاتشا أحكامها إذا أعلن الشخص توبته والتمس التصالح مع المجتمع . ويقصد بهذه المحاكم مساعدة المجتمع على المشاركة في عملية العدالة والمصالحة في البلد.

وعلى الصعيد الدولي، أنشأ مجلس الأمن في 8 نوفمبر 1994 المحكمة الجنائية الدولية لرواندا، التي يقع مقرها حالياً في أروشا، بتنزانيا. وبدأت التحقيقات في أيار/مايو 1995. وقدم أول المشتبه فيهم إلى المحكمة في ايار/مايو 1996 وبدأ النظر في أولى القضايا في كانون الثاني/يناير 1997. ولهذه المحكمة التابعة للأمم المتحدة اختصاص بالنظر في جميع انتهاكات حقوق الإنسان الدولية المرتكبة في رواندا خلال الفترة بين كانون الثاني/يناير وكانون الأول/ديسمبر 1994، ولها القدرة على محاكمة كبار أعضاء الحكومة والقوات المسلحة الذين ربما يكونون قد هربوا إلى خارج البلد ويمكن بغير المحكمة أن يفلتوا من العقاب. وقد أصدرت المحكمة منذ ذلك الحين حكمها على رئيس الوزراء خلال الإبادة الجماعية جان كامباندا بعقوبة السجن مدى الحياة. وكانت أيضاً أول محكمة دولية تدين أحد المشتبه فيهم بارتكاب تهمة الاغتصاب باعتباره جريمة ضد الإنسانية ومن جرائم الإبادة الجماعية. كما أن المحكمة حاكمت ثلاثة من أصحاب وسائل الإعلام المتهم كل منهم باستخدام وسائل الإعلام الخاصة به للتحريض على الكراهية العرقية والقتل الجماعي. وبحلول نيسان/أبريل 2007، كانت قد أصدرت سبعة وعشرين حكماً على ثلاثة وثلاثين متهماً.

حربا الكونغو الأولى والثانية

رواندا اليوم

انظر أيضاً

- تاريخ أفريقيا

- تاريخ بوروندي

- قائمة ملوك رواندا

- قائمة رؤساء رواندا

- سياسة رواندا

- رئيس وزراء رواندا

- رواندا-اوروندي

- رواندا

ملاحظات تفصيلية

الهامش

- ^ "International Boundary Study: Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire) -- Rwanda Boundary" (PDF). Department of State, Washington, D.C., US. 1965-06-15. Retrieved 2006-06-05.

- ^ Newbury, David (1992). Kings and clans: Ijwi Island and the Lake Kivu Rift, 1780-1840. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 239 & 270. ISBN 978-0-299-12894-4. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Re-imagining Rwanda: Conflict, Survival and Disinformation in the Twentieth Century" (PDF). School of Oriental and African Studies, University of England (Cambridge University Press). 2002-03-01. Retrieved 2006-06-05.

- ^ Adam Curtis documentary All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace. BBC, episode 3.

- ^ "The Teaching of the History of Rwanda: A Participatory Approach (A Reference Book for Secondary Schools in Rwanda)" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Research, Kigali, Rwanda, and UC Berkeley Human Rights Center, Berkeley, US. 2007-03-01. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ "Julius Nyerere: Lifelong Learning and Informal Education". infed (Informal Education website), London, UK. 2007-05-27. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

للاستزادة

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre. The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History trans Scott Straus

- Dallaire, Romeo. "Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda". Arrow Books (2003). ISBN 0-09-947893-5

- "History" chapter of Des Forges, Alison (1999). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-171-8.

- Lemarchand, René (2009). The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4120-4.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2001). When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-10280-5.

- Pottier, Johan (2002). Re-imagining Rwanda: Conflict, Survival and Disinformation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52873-3.

- Prunier, Gérard (1995). The Rwanda Crisis, 1959–1994: History of a Genocide (Hardcover ed.). London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-243-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Prunier, Gérard (2009). Africa's World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537420-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2009

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2016

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from February 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2016

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from November 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2009

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2010

- تاريخ رواندا

- World Digital Library related