صينية وو

| وو Wu | |

|---|---|

| [吳語] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-wuu-Hant (help)/[吴语] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-wuu-Hans (help) Hhu22 nyy44 | |

وو (Wú Yǔ) مكتوبة بالحروف الصينية | |

| موطنها | الصين؛ المجتمعات وراء البحار القادمة من مناطق ناطقة بالوو في الصين – وخصوصاً كوريا الجنوبية، اليابان، جنوب أوروبا، الولايات المتحدة (مدينة نيويورك) |

| العرق | وو (صينيو هان) |

الناطقون الأصليون | 80 مليون (2007)ne2007 |

| اللهجات |

|

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-3 | wuu |

| Glottolog | wuch1236 |

| |

| صينية وو | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الصينية المبسطة | 吴语 | ||||||||||||||||||

| الصينية التقليدية | 吳語 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

وو (بالحروف الصينية: 吳語 , nguphin: ngu niu, Soochowish: أصد: [ɦəu²² ɲy⁴⁴]، الشانغهائية: أصد: [ɦu²² ɲy⁴⁴] ڤوسيكيش: أصد: [ŋu21 nʲy232] ) هي مجموعة من تنويعات اللغة الصينية المتشابهة لغوياً والمرتبطة تاريخياً وخصوصاً المحكية أساساً في مقاطعة ژىجيانگ، بلدية شانغهاي وجنوب مقاطعة جيانگسو.

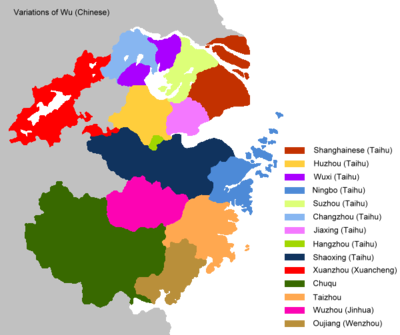

لهجات وو الرئيسية تضم تلك المحكية في شانغهاي وسوژو وووشي، ونژو و ننگبو وهانگژو وشاوشينگ وجينهوا و يونگكانگ. ناطقو الوو، مثل تشيانگ كاي-شك، لو شون و تساي يوانپـِيْ، شغلوا مناصب بالغة الأهمية في الثقافة والسياسة الصينية المعاصرة. كما يمكن العثور على لغة وو مستخدمة في اوپرا شاوشينگ، التي تأتي في المقام الثاني في الشعبية الوطنية بعد اوپرا بكين؛ وكذلك في أداء الفنانين ذوي الشعبية والكوميدي ژو ليبو. كما تُحكى وو في عدد كبير من تجمعات الشتات، بمراكز بارزة للمهاجرين من چينگتيان و ونژو.

سوژو has traditionally been the linguistic center of the Wu dialects and was likely the first place the distinct variety of Sinitic known as Wu developed. سوژو وو تُعتبر على نطاق واسع أكثر اللهجات تمثيلاً (لغويا) لهذه العائلة. It was mostly the basis of the Wu lingua franca that developed in Shanghai leading to the formation of modern الشانغهائية, which as a center of economic power and possessing the largest population of Wu speakers, has attracted the most attention. بسبب تأثير الشانغهائية، Wu as a whole is incorrectly labelled in English as simply, "الشانغهائية"، when introducing the dialect family to non-specialists. Wu is the more accurate terminology for the greater grouping that the Shanghai dialect is part of; other less precise terms include "Jiangnan speech" (江南話), "Jiangzhe (جيانگسو–ژىجيانگ) speech" (江浙話), and less commonly "Wuyue speech" (吳越語).

This dialect group (Southern Wu in particular) is well-known among linguists and sinologists as being one of the most internally diverse among the Sinitic language groups, with very little mutual intelligibility among varieties within the dialect clusters. Among speakers of other Sinitic languages, Wu is often subjectively judged to be soft, light, and flowing. There is an idiom in Mandarin that specifically describes these qualities of Wu speech: Ngu nung nioe niu (吴侬软语), which literally means "the tender speech of Wu". On the other hand, some Wu varieties like الونژوئية have gained notoriety for their incomprehensibility to both Wu and non-Wu speakers alike, so much so that الونژوئية was used during the Second World War to avoid Japanese interception.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Wu dialects have the largest vowel quality inventories in the world. The Jinhui dialect spoken in Shanghai's Fengxian District has 20 vowel qualities, the most among all world languages.[1][2]

Wu dialects are typified linguistically as having preserved the voiced initials of Middle Chinese, having a majority of Middle Chinese tones undergo a register split, and preserving a checked tone typically terminating in a glottal stop,[3] although some dialects maintain the tone without the stop and certain dialects of Southern Wu have undergone or are starting to undergo a process of devoicing. The historical relations which determine Wu classification primarily consist in two main factors: firstly, geography, both in terms of physical geography and distance south or away from Mandarin, that is, Wu dialects are part of a Wu–Min dialect continuum from southern Jiangsu to southern Hujian and Chaozhou.[بحاجة لمصدر] The second factor is the drawing of historical administrative boundaries, which, in addition to physical barriers, limit mobility and in the majority of cases more or less determine the boundary of a Wu dialect.

Wu Chinese, along with Min, is also of great significance to historical linguists due to their retention of many ancient features. These two languages have proven pivotal in determining the phonetic history of the Sinitic languages.

More pressing concerns of the present are those of language preservation. Many within and outside of China fear that the increased usage of Mandarin may eventually altogether supplant the languages that have no written form, legal protection, or official status and are officially barred from use in public discourse. However, many analysts believe that a stable state of diglossia will endure for at least several generations if not indefinitely.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التوزيع الجغرافي

تنويعات وو تنتشر في معظم مقاطعة ژىجيانگ وبلدية شانغهاي وجنوب مقاطعة جيانگسو، وكذلك أجزاء أصغر في مقاطعات آنهوي وجيانگشي وفوجيان.[4] Many are located in the lower Yangzi valley.[5][6]

التبويب

التنويعات

In the Language Atlas of China (1987), Wu was divided into six subgroups:

الصوتيات

النطق الفصيح والدارج في الشانغهائية

| 字 | پنين | الترجمة | الأدبي | الدارج |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 家 | jiā | بيت | tɕia˥˨ | ka˥˨ |

| 顏 | yán | وجه | ɦiɪ˩˩˧ | ŋʱɛ˩˩˧ |

| 櫻 | yīng | كرز | ʔiŋ˥˨ | ʔã˥˨ |

| 孝 | xiào | تبجيل السلف | ɕiɔ˧˧˥ | hɔ˧˧˥ |

| 學 | xué | التعلم | ʱjaʔ˨ | ʱoʔ˨ |

| 物 | wù | شيء | vəʔ˨ | mʱəʔ˨ |

| 網 | wǎng | web | ʱwɑŋ˩˩˧ | mʱɑŋ˩˩˧ |

| 鳳 | fèng | male phoenix | voŋ˩˩˧ | boŋ˩˩˧ |

| 肥 | féi | سمين | vi˩˩˧ | bi˩˩˧ |

| 日 | rì | sun | zəʔ˨ | ȵʱiɪʔ˨ |

| 人 | rén | person | zən˩˩˧ | ȵʱin˩˩˧ |

| 鳥 | niǎo | bird | ʔȵiɔ˧˧˥ | tiɔ˧˧˥[بحاجة لمصدر] |

انظر أيضاً

- Long-short (romanization)

- Chinatowns in Queens § Flushing

- Wo Bau-Sae

- Jiangnan

- List of varieties of Chinese

- وو (منطقة)

- Speakers of Wu Chinese

- وويوى

الهامش

- ^ Chuan-Chao Wang; Qi-Liang Ding; Huan Tao; Hui Li (2012). "Comment on "Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa"". Science. 335 (6069): 657. doi:10.1126/science.1207846. Retrieved 19 فبراير 2012.

- ^ 奉贤金汇方言"语音最复杂" 元音巅峰值达20个左右 (in Chinese). Eastday. 14 فبراير 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJerry Norman 1988/2008 180 - ^ "Wu Language". Greentranslations.com. Retrieved 22 أبريل 2013.

- ^ Nils Göran David Malmqvist (2010). Bernhard Karlgren: portrait of a scholar. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 302. ISBN 1-61146-000-X. Retrieved 10 مارس 2012.

In 1925, Chao Yuen Ren returned to Qinghua University. The following year, he began his comprehensive study of the Wu dialects in the lower Yangzi valley. In 1929, he was appointed head of the section of linguistics in the Academia Sinica and became responsible for the planning and the

() - ^ N. G. D. Malmqvist (2010). Bernhard Karlgren: Portrait of a Scholar. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1-61146-001-8. Retrieved 10 مارس 2012.

In 1925, Chao Yuen Ren returned to Qinghua University. The following year, he began his comprehensive study of the Wu dialects in the lower Yangzi valley. In 1929, he was appointed head of the section of linguistics in the Academia Sinica and became responsible for the planning and the

()

- Chao, Yuen Ren (1967). "Contrastive Aspects of the Wu Dialects". Language. 43 (1): 92–101. doi:10.2307/411386. JSTOR 411386.

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006). Introduction to Chinese Dialectology. Munich: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- Snow, Donald B. Cantonese as Written Language: The Growth of a Written Chinese Vernacular. Hong Kong University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-962-209-709-4. ISBN 962-209-709-X.

الهامش

- [1] 袁家驊 – 漢語方言概要

وصلات خارجية

مراجع للهجات وو

- glossika.com

- Shanghainese Wu Dictionary – Search in Mandarin, IPA, or[dead link]

- Classification of Wu Dialects – By James Campbell

- Tones in Wu Dialects – Compiled by James Campbell

- Linguistic Forum of Wu Chinese (صينية: 吴语论坛�)[dead link]

A BBS set up in 2004, in which topics such as phonology, grammar, orthography and romanization of Wu Chinese are widely talked about. The cultural and linguistic diversity within China is also a significant concerning of this forum.

A website aimed at modernization of Wu Chinese, including basics of Wu, Wu romanization scheme, pronunciation dictionaries of different dialects, Wu input method development, Wu research literatures, written Wu experiment, Wu orthography, a discussion forum etc.

Excellent reference on Wu Chinese, including tones of the sub-dialects.

- Tatoeba Project Tatoeba.org - Examples sentences in Shanghainese dialect, and in Suzhouan dialect.

- Wu wordlist available through Kaipuleohone

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

مقالات

- Globalization, National Culture and the Search for Identity: A Chinese Dilemma (1st Quarter of 2006, Media Development) – A comprehensive article, written by Wu Mei and Guo Zhenzhi of World Association for Christian Communication, related to the struggle for national cultural unity by current Chinese Communist national government while desperately fighting for preservation on Chinese regional cultures that have been the precious roots of all Han Chinese people (including Hangzhou Wu dialect). Excellent for anyone doing research on Chinese language linguistic, anthropology on Chinese culture, international business, foreign languages, global studies, and translation/interpretation.

- Modernisation a Threat to Dialects in China – An excellent article originally from Straits Times Interactive through YTL Community website, it provides an insight of Chinese dialects, both major and minor, losing their speakers to Standard Mandarin due to greater mobility and interaction. Excellent for anyone doing research on Chinese language linguistic, anthropology on Chinese culture, international business, foreign languages, global studies, and translation/interpretation.

- Middlebury Expands Study Abroad Horizons – An excellent article including a section on future exchange programs in learning Chinese language in Hangzhou (plus colorful, positive impression on the Hangzhou dialect, too). Requires registration of online account before viewing.

- Mind your language (from The Standard, Hong Kong) – This newspaper article provides a deep insight on the danger of decline in the usage of dialects, including Wu dialects, other than the rising star of Standard Mandarin. It also mentions an exception where some grassroots’ organizations and, sometimes, larger institutions, are the force behind the preservation of their dialects. Another excellent article for research on Chinese language linguistics, anthropology on Chinese culture, international business, foreign languages, global studies, and translation/interpretation.

- China: Dialect use on TV worries Beijing (originally from Straits Times Interactive, Singapore and posted on AsiaMedia Media News Daily from UCLA) – Article on the use of dialects other than standard Mandarin in China where strict media censorship is high.

- Standard or Local Chinese – TV Programs in Dialect (from Radio86.co.uk) – Another article on the use of dialects other than standard Mandarin in China.

- CS1 uses الصينية-language script (zh)

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- Articles citing Nationalencyklopedin

- Language articles with unsupported infobox fields

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2011

- Articles with dead external links from August 2014

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة الصينية المبسطة

- Use dmy dates from June 2011

- Wu Chinese

- Chinese languages in Singapore

- Subject–verb–object languages