ديبلودوكس

| ديبلودوكس | |

|---|---|

| |

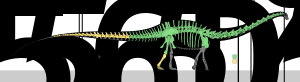

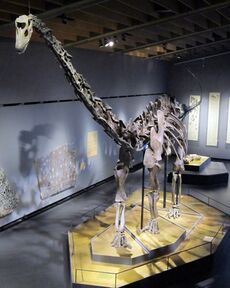

| هيكل عظمي للديناصور د. كارنگي (أو "ديپ") معروض في متحف كارنگى للتاريخ الطبيعي؛ يعتبر أشهر هيكل عظمي لديناصور في العالم.[1][2] | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | Diplodocus |

| Type species | |

| †ديپلودوكس لونگوس (اسم مبهم) مارش، 1878

| |

| أنواع أخرى | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

ديپلودوكس (إنگليزية: Diplodocus، /dɪˈplɒdəkəs/،[3][4] /daɪˈplɒdəkəs/,[4] or /ˌdɪploʊˈdoʊkəs/[3])، هو جنس من الديناصورات الصوروپودية مزدوجة الدعامة، اكتشفت أحفوراتها لأول مرة عام 1877 بواسطة صمويل ويلستون. الاسم العام، صاغعه أوثنيال تشارلز مارش عام 1878، وهو مصطلح لاتيني-جديد مشتق من الكلمة اليونانية διπλός (ديپلوس) أي "مزدوج" وδοκός (دوكوس) "الشعاع"،[3][5] في إشارة إلى العظام السبعانية مزدوجة-الشعاع الموجودة في الجانب السفلي من الذيل، والتي كانت تعتبر فريدة من نوعها.

كان هذا النوع من الديناصورات يعيش فيما يعرف حالياً بوسط-غرب أمريكا الشمالية، في نهاية العصر الجوراسي. وهو أحد أحافير الديناصورات الأكثر شيوعاً التي عُثر عليها في الطبقات المتوسطة-العليا من تكوين موريسون، ويعود عمرها إلى حوالي 154-152 مليون سنة، خلال أواخر العصر الكيمريدجي.[6] يسجل تشكيل موريسون بيئة ووقت تسيطر عليهما الديناصورات الصوروپودية العملاقة، مثل الأپاتوصور، الباروصور، البراكيوصور، البرونتوصور، والكاماراصور.[7] قد يكون حجمها الكبير رادعًا للديناصورات المفترسة الألوصور، السيراتوصور: عُثر على بقاياهم في نفس الطبقات، مما يشير إلى أنهم كانوا يتعايشون مع الديپلودوكس.

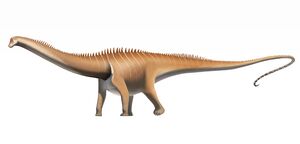

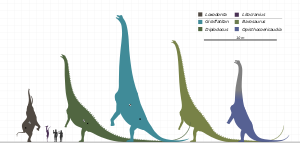

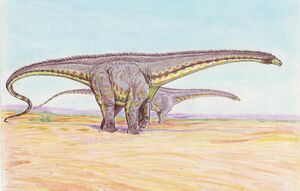

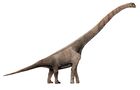

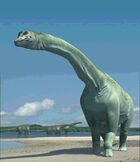

"الديپلودوكس" من بين أكثر الديناصورات التي يمكن التعرف عليها بسهولة، بشكلها الصوروپودي النموذجي، وعنقها الطويل وذيلها، وأرجلها الأربعة المتينة. لعدة سنوات، كان الديپلودوكس أطول ديناصور معروف.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الوصف

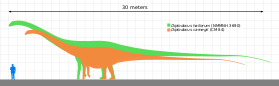

Among the best-known sauropods, Diplodocus were very large, long-necked, quadrupedal animals, with long, whip-like tails. Their forelimbs were slightly shorter than their hind limbs, resulting in a largely horizontal posture. The skeletal structure of these long-necked, long-tailed animals supported by four sturdy legs have been compared with suspension bridges.[8] In fact, D. carnegii is currently one of the longest dinosaurs known from a complete skeleton,[8] with a total length of 24–26 meters (79–85 ft).[9][10] Modern mass estimates for D. carnegii have tended to be in the 12–14.8-metric-ton (13.2–16.3-short-ton) range.[9][11][10]

D. hallorum, known from partial remains, was even larger, and is estimated to have been the size of four elephants.[12] When first described in 1991, discoverer David Gillette calculated it to be 33 m (110 ft) long based on isometric scaling with D. carnegii. However, he later stated that this was unlikely and estimated it to be 39 - 45 meters (130 - 150 ft) long, suggesting that some individuals may have been up to 52 m (171 ft) long and weighed 80 to 100 metric tons,[13] making it the longest known dinosaur (excluding those known from exceedingly poor remains, such as Amphicoelias or Maraapunisaurus). The estimated length was later revised downward to 30.5–35 m (100–115 ft) and later on to 29–33.5 m (95–110 ft)[14][15][16][10][9] based on findings that show that Gillette had originally misplaced vertebrae 12–19 as vertebrae 20–27; according to Gregory S. Paul, a 29 m (95 ft) long D. hallorum weighs 23 metric tons (25 short tons) in body mass.[9] The nearly complete D. carnegii skeleton at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on which size estimates of D. hallorum are mainly based, also was found to have had its 13th tail vertebra come from another dinosaur, throwing off size estimates for D. hallorum even further. While dinosaurs such as Supersaurus were probably longer, fossil remains of these animals are only fragmentary.[17]

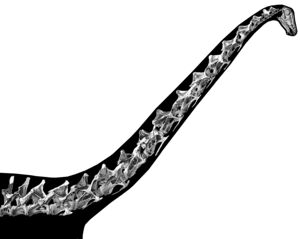

Diplodocus had an extremely long tail, composed of about 80 caudal vertebrae,[18] which are almost double the number some of the earlier sauropods had in their tails (such as Shunosaurus with 43), and far more than contemporaneous macronarians had (such as Camarasaurus with 53). Some speculation exists as to whether it may have had a defensive[19] or noisemaking (by cracking it like a coachwhip)[20] or, as more recently suggested, tactile function.[21] The tail may have served as a counterbalance for the neck. The middle part of the tail had "double beams" (oddly shaped chevron bones on the underside, which gave Diplodocus its name). They may have provided support for the vertebrae, or perhaps prevented the blood vessels from being crushed if the animal's heavy tail pressed against the ground. These "double beams" are also seen in some related dinosaurs. Chevron bones of this particular form were initially believed to be unique to Diplodocus; since then they have been discovered in other members of the diplodocid family as well as in non-diplodocid sauropods, such as Mamenchisaurus.[22]

Like other sauropods, the manus (front "feet") of Diplodocus were highly modified, with the finger and hand bones arranged into a vertical column, horseshoe-shaped in cross section. Diplodocus lacked claws on all but one digit of the front limb, and this claw was unusually large relative to other sauropods, flattened from side to side, and detached from the bones of the hand. The function of this unusually specialized claw is unknown.[23]

No skull has ever been found that can be confidently said to belong to Diplodocus, though skulls of other diplodocids closely related to Diplodocus (such as Galeamopus) are well known. The skulls of diplodocids were very small compared with the size of these animals. Diplodocus had small, 'peg'-like teeth that pointed forward and were only present in the anterior sections of the jaws.[24] Its braincase was small. The neck was composed of at least 15 vertebrae and may have been held parallel to the ground and unable to be elevated much past horizontal.[25]

Skin

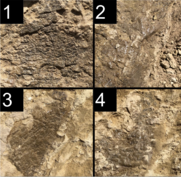

The discovery of partial diplodocid skin impressions in 1990 showed that some species had narrow, pointed, keratinous spines, much like those on an iguana. The spines could be up to 18 centimeters (7.1 in) long, on the "whiplash" portion of their tails, and possibly along the back and neck as well, similarly to hadrosaurids.[26][27] The spines have been incorporated into many recent reconstructions of Diplodocus, notably Walking with Dinosaurs.[28] The original description of the spines noted that the specimens in the Howe Quarry near Shell, Wyoming were associated with skeletal remains of an undescribed diplodocid "resembling Diplodocus and Barosaurus."[26] Specimens from this quarry have since been referred to Kaatedocus siberi and Barosaurus sp., rather than Diplodocus.[6][29]

Fossilized skin of Diplodocus sp., discovered at the Mother's Day Quarry, exhibits several different types of scale shapes including rectangular, polygonal, pebble, ovoid, dome, and globular. These scales range in size and shape depending upon their location on the integument, the smallest of which reach about 1mm while the largest 10 mm. Some of these scales show orientations that may indicate where they belonged on the body. For instance, the ovoid scales are closely clustered together and look similar to scales in modern reptiles that are located dorsally. Another orientation on the fossil consists of arching rows of square scales that interrupts nearby polygonal scale patterning. It is noted that the arching scale rows look similar to the scale orientations seen around crocodilian limbs, suggesting that this area may have also originated from around a limb on the Diplodocus. The skin fossil itself is small in size, reaching less than 70 cm in length. Due to the vast amount of scale diversity seen within such a small area, as well as the scales being smaller in comparison to other diplodocid scale fossils, and the presence of small and potentially “juvenile” material at the Mother’s Day Quarry, it is hypothesized that the skin originated from a small or even “juvenile” Diplodocus.[30]

Discovery and history

Bone Wars and Diplodocus longus

The first record of Diplodocus comes from Marshall P. Felch’s quarry at Garden Park near Cañon City, Colorado, when several fossils were collected by Benjamin Mudge and Samuel Wendell Williston in 1877. The first specimen (YPM VP 1920) was very incomplete, consisting only of two complete caudal vertebrae, a chevron, and several other fragmentary caudal vertebrae. The specimen was sent to the Yale Peabody Museum and was named Diplodocus longus ('long double-beam') by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878.[31] Marsh named Diplodocus during the Bone Wars, his competition with Philadelphian paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope to collect and describe as many fossil taxa as possible.[32] Though several more complete specimens have been attributed to D. longus,[33][34] detailed analysis has discovered that this type specimen is actually dubious, which is not an ideal situation for the type species of a well-known genus like Diplodocus. A petition to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature was being considered which proposed to make D. carnegii the new type species.[6][35] This proposal was rejected by the ICZN and D. longus has been maintained as the type species.[36]

Although the type specimen was very fragmentary, several additional diplodocid fossils were collected at Felch’s quarry from 1877 to 1884 and sent to Marsh, who then referred them to D. longus. One specimen (USNM V 2672), an articulated complete skull, mandibles, and partial atlas was collected in 1883, and was the first complete Diplodocid skull to be reported.[37][38] Tschopp et al.’s analysis placed it as an indeterminate diplodocine in 2015 due to the lack of overlap with any diagnostic Diplodocus postcranial material, as was the fate with all skulls assigned to Diplodocus.[6]

Second Dinosaur Rush and Diplodocus carnegii

After the end of the Bone Wars, many major institutions in the eastern United States were inspired by the depictions and finds by Marsh and Cope to assemble their own dinosaur fossil collections.[32] The competition to mount the first sauropod skeleton specifically was the most intense, with the American Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Field Museum of Natural History all sending expeditions to the west to find the most complete sauropod specimen, bring it back to the home institution, and mount it in their fossil halls.[32] The American Museum of Natural History was the first to launch an expedition, finding a semi-articulated partial postcranial skeleton containing many vertebrae of Diplodocus in at Como Bluff in 1897. The skeleton (AMNH FR 223) was collected by Barnum Brown and Henry Osborn, who shipped the specimen to the AMNH and it was briefly described in 1899 by Osborn, who referred it to D. longus. It was later mounted—the first Diplodocus mount made—and was the first well preserved individual skeleton of Diplodocus discovered.[6][33] In Emmanuel Tschopp et al.'s phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocidae, AMNH FR 223 was found to be not a skeleton of D. longus, but the later named species D. hallorum.[6]

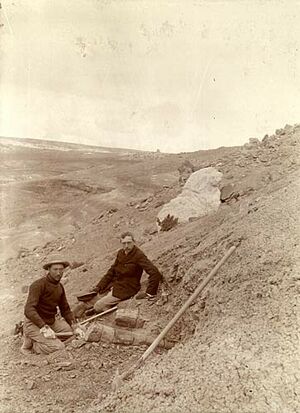

The most notable Diplodocus find also came in 1899, when crew members from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History were collecting fossils in the Morrison Formation of Sheep Creek, Wyoming, with funding from Scottish-American steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie, they discovered a massive and well preserved skeleton of Diplodocus.[40] The skeleton was collected that year by Jacob L. Wortman and several other crewmen under his direction along with several specimens of Stegosaurus, Brontosaurus parvus, and Camarasaurus preserved alongside the skeleton.[40] The skeleton (CM 84) was preserved in semi articulation and was very complete, including 41 well preserved vertebrae from the mid caudals to the anterior cervicals, 18 ribs, 2 sternal ribs, a partial pelvis, right scapulocoracoid, and right femur. In 1900, Carnegie crews returned to Sheep Creek, this expedition led by John Bell Hatcher, William Jacob Holland, and Charles Gilmore, and discovered another well preserved skeleton of Diplodocus adjacent to the specimen collected in 1899.[6][40] The second skeleton (CM 94) was from a smaller individual and had preserved fewer vertebrae, but preserved more caudal vertebrae and appendicular remains than CM 84.[40][6] Both of the skeletons were named and described in great detail by John Bell Hatcher in 1901, with Hatcher making CM 84 the type specimen of a new species of Diplodocus, Diplodocus carnegii ("Andrew Carnegie's double beam"),[6][40] with CM 94 becoming the paratype.[40]

It wasn't until 1907, that the Carnegie Museum of Natural History created a composite mount of Diplodocus carnegii that incorporated CM 84 and CM 94 along with several other specimens and even other taxa were used to complete the mount, including a skull molded based on USNM 2673, a skull assigned to Galeamopus pabsti.[41][6] The Carnegie Museum mount became very popular, being nicknamed "Dippy" by the populace, eventually being cast and sent to museums in London, Berlin, Paris, Vienna, Bologna, St. Petersburg, Buenos Aires, Madrid, and Mexico City from 1905 to 1928.[42] The London cast specifically became very popular; its casting was requested by King Edward VII and it was the first sauropod mount put on display outside of the United States.[42] The goal of Carnegie in sending these casts overseas was apparently to bring international unity and mutual interest around the discovery of the dinosaur.[43]

Dinosaur National Monument

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History made another landmark discovery in 1909 when Earl Douglass unearthed several caudal vertebrae from Apatosaurus in what is now Dinosaur National Monument on the border region between Colorado and Utah, with the sandstone dating to the Kimmeridgian of the Morrison Formation. From 1909 to 1922, with the Carnegie Museum excavating the quarry, eventually unearthing over 120 dinosaur individuals and 1,600+ bones, many of the associated skeletons being very complete and are on display in several American museums. In 1912, Douglass found a semi articulated skull of a diplodocine with mandibles (CM 11161) in the Monument. Another skull (CM 3452) was found by Carnegie crews in 1915, bearing 6 articulated cervical vertebrae and mandibles, and another skull with mandibles (CM 1155) was found in 1923. All of the skulls found at Dinosaur National Monument were shipped back to Pittsburgh and described by William Jacob Holland in detail in 1924, who referred the specimens to D. longus.[44] This assignment was also questioned by Tschopp, who stated that all of the aforementioned skulls could not be referred to any specific diplodocine. Hundreds of assorted postcranial elements were found in the Monument that have been referred to Diplodocus, but few have been properly described.[6] A nearly complete skull of a juvenile Diplodocus was collected by Douglass in 1921, and it is the first known from a Diplodocus.[45]

Another Diplodocus skeleton was collected at the Carnegie Quarry in Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, by the National Museum of Natural History in 1923. The skeleton (USNM V 10865) is one of the most complete known from Diplodocus, consisting of a semi-articulated partial postcranial skeleton, including a well preserved dorsal column. The skeleton was briefly described by Charles Gilmore in 1932, who also referred it to D. longus, and it was mounted in the fossil hall at the National Museum of Natural History the same year. In Emmanuel Tschopp et al.'s phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocidae, USNM V 10865 was also found to be an individual of D. hallorum.[6][46]

The Denver Museum of Nature and Science also collected a Diplodocus specimen in Dinosaur National Monument, a partial postcranial skeleton including cervical vertebrae, that was later mounted in the museum. Although not described in detail, Tschopp and colleagues determined that this skeleton also belonged to D. hallorum.[6]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Recent discoveries and Diplodocus hallorum

Few Diplodocus finds came for many years until 1979, when three hikers came across several vertebrae stuck in elevated stone next to several petroglyphs in a canyon west of San Ysidro, New Mexico. The find was reported to the New Mexican Museum of Natural History, who dispatched an expedition led by David D. Gillette in 1985, that collected the specimen after several visits from 1985 to 1990. The specimen was preserved in semi-articulation, including 230 gastroliths, with several vertebrae, partial pelvis, and right femur and was prepared and deposited at the New Mexican Museum of Natural History under NMMNH P-3690. The specimen was not described until 1991 in the Journal of Paleontology, where Gillette named it Seismosaurus halli (Jim and Ruth Hall's seismic lizard), though in 1994, Gillette published an amendment changing the name to S. hallorum.[13][47] In 2004 and later 2006, Seismosaurus was synonymized with Diplodocus and even suggested to be synonymous with the dubious D. longus and later Tschopp et al.'s phylogenetic analysis in 2015 supported the idea that many specimens referred to D. longus actually belonged to D. hallorum.[6]

In 1994, the Museum of the Rockies discovered a very productive fossil site at Mother's Day Quarry in Carbon County, Montana from the Salt Wash member of the Morrison Formation that was later excavated by the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science in 1996, and after that the Bighorn Basin Paleontological Institute in 2017. The quarry was very productive, having mostly isolated Diplodocus bones from juveniles to adults in pristine preservation. The quarry notably had a great disparity between the amount of juveniles and adults in the quarry, as well as the frequent preservation of skin impressions, pathologies, and some articulated specimens from Diplodocus.[47][30] One specimen, a nearly complete skull of a juvenile Diplodocus, was found at the quarry and is one of few known and highlighted ontogenetic dietary changes in the genus.[48]

Classification and species

Phylogeny

Diplodocus is both the type genus of, and gives its name to, the Diplodocidae, the family in which it belongs.[37] Members of this family, while still massive, have a markedly more slender build than other sauropods, such as the titanosaurs and brachiosaurs. All are characterised by long necks and tails and a horizontal posture, with forelimbs shorter than hind limbs. Diplodocids flourished in the Late Jurassic of North America and possibly Africa.[18]

A subfamily, the Diplodocinae, was erected to include Diplodocus and its closest relatives, including Barosaurus. More distantly related is the contemporaneous Apatosaurus, which is still considered a diplodocid, although not a diplodocine, as it is a member of the sister subfamily Apatosaurinae.[49][50] The Portuguese Dinheirosaurus and the African Tornieria have also been identified as close relatives of Diplodocus by some authors.[51][52] Diplodocoidea comprises the diplodocids, as well as the dicraeosaurids, rebbachisaurids, Suuwassea,[49][50] Amphicoelias[52] possibly Haplocanthosaurus,[53] and/or the nemegtosaurids.[54] The clade is the sister group to Macronaria (camarasaurids, brachiosaurids and titanosaurians).[53][54]

A Cladogram of the Diplodocidae after Tschopp, Mateus, and Benson (2015) below:[6]

| Diplodocidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Valid species

- D. carnegii (also spelled D. carnegiei), named after Andrew Carnegie, is the best known, mainly due to a near-complete skeleton known as Dippy (specimen CM 84) collected by Jacob Wortman, of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and described and named by John Bell Hatcher in 1901.[55] It was reconsidered as the type species for Diplodocus.[35]

- D. hallorum, first described in 1991 by Gillette as Seismosaurus halli from a partial skeleton comprising vertebrae, pelvis and ribs (specimen NMMNH P-3690).[56] As the specific name honours two people, Jim and Ruth Hall (of Ghost Ranch[57]), George Olshevsky later suggested to emend the name as S. hallorum, using the mandatory genitive plural; Gillette then emended the name,[13] which usage has been followed by others, including Carpenter (2006).[14] In 2004, a presentation at the annual conference of the Geological Society of America made a case for Seismosaurus being a junior synonym of Diplodocus.[58] This was followed by a much more detailed publication in 2006, which not only renamed the species Diplodocus hallorum, but also speculated that it could prove to be the same as D. longus.[59] The position that D. hallorum should be regarded as a specimen of D. longus was also taken by the authors of a redescription of Supersaurus, refuting a previous hypothesis that Seismosaurus and Supersaurus were the same.[60] A 2015 analysis of diplodocid relationships noted that these opinions are based on the more complete referred specimens of D. longus. The authors of this analysis concluded that those specimens were indeed the same species as D. hallorum, but that D. longus itself was a nomen dubium.[6]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Nomina dubia (doubtful species)

- D. longus, the type species, is known from two complete and several fragmentary caudal vertebrae from the Morrison Formation (Felch Quarry) of Colorado. Though several more complete specimens have been attributed to D. longus,[34] detailed analysis has suggested that the original fossil lacks the necessary features to allow comparison with other specimens. For this reason, it has been considered a nomen dubium, which Tschopp et al. regarded as not an ideal situation for the type species of a well-known genus like Diplodocus. A petition to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) was being considered, which proposed to make D. carnegii the new type species.[6][35] The proposal was rejected by the ICZN and D. longus has been maintained as the type species.[36] However, in comments responding to the petition, some authors regarded D. longus as potentially valid after all.[61][62]

- D. lacustris ("of the lake") is a nomen dubium named by Marsh in 1884 based on specimen YPM 1922 found by Arthur Lakes, consisting of the snout and upper jaw of a smaller animal from Morrison, Colorado.[37] The remains are now believed to have been from an immature animal, rather than from a separate species.[63] Mossbrucker et al., 2013 surmised that the dentary and teeth of Diplodocus lacustris was actually from Apatosaurus ajax.[64] Later in 2015, it was concluded that the snout of the specimen actually belonged to Camarasaurus.[6]

Formerly assigned species

- Diplodocus hayi was named by William Jacob Holland in 1924 based on a braincase and partial postcranial skeleton (HMNS 175), including a nearly complete vertebral column, found in the Morrison Formation strata near Sheridan, Wyoming.[6][44] D. hayi remained a species of Diplodocus until reassessment by Emmanuel Tschopp and colleagues determined that it was its own genus, Galeamopus, in 2015. The reassessment also found that the skulls AMNH 969 and USNM 2673 were not Diplodocus either and actually referred specimens of Galeamopus.[6]

Paleobiology

Due to a wealth of skeletal remains, Diplodocus is one of the best-studied dinosaurs. Many aspects of its lifestyle have been subjects of various theories over the years.[22] Comparisons between the scleral rings of diplodocines and modern birds and reptiles suggest that they may have been cathemeral, active throughout the day at short intervals.[65]

Marsh and then Hatcher[40] assumed that the animal was aquatic, because of the position of its nasal openings at the apex of the cranium. Similar aquatic behavior was commonly depicted for other large sauropods, such as Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus. A 1951 study by Kenneth A. Kermack indicates that sauropods probably could not have breathed through their nostrils when the rest of the body was submerged, as the water pressure on the chest wall would be too great.[66] Since the 1970s, general consensus has the sauropods as firmly terrestrial animals, browsing on trees, ferns, and bushes.[67]

Scientists have debated as to how sauropods were able to breathe with their large body sizes and long necks, which would have increased the amount of dead space. They likely had an avian respiratory system, which is more efficient than a mammalian and reptilian system. Reconstructions of the neck and thorax of Diplodocus show great pneumaticity, which could have played a role in respiration as it does in birds.[68]

وضعية الجسم

لقد تغير تصوير وضعية جسم الديبلودوكس بشكل كبير على مر السنين. على سبيل المثال، أعيد بناء التصور الكلاسيكي لعام 1910 الذي قام به أوليڤر هاي لاثنين من "الديبلودوكس" بأطراف مفلطحة تشبه السحلية على ضفاف أحد الأنهار. جادل هاي بأن "ديبلودوكس" كان لديه مشية مترامية الأطراف تشبه السحلية مع أرجل مفلطحة بشكل كبير[70] وكان يؤديه جوستاڤ تورنييه. هذه الفرضية عارضها وليام جاكوب هولاند، الذي أظهر أن "الديبلودوكس" بتلك الأطراف الضخمة كان سيحتاج إلى خندق لسحب بطنه من خلاله.[71] أدت اكتشافات آثار أقدام الصوروپودات في الثلاثينيات إلى توقف نظرية هاي.[67]

لاحقاً، غالباً ما كان يتم تصوير الديبلودوكسات بأعناق مرفوعة في الهواء، مما يسمح لهم بالرعي من الأشجار العالية. خلصت الدراسات التي تبحث في مورفولوجيا أعناق الصوروپودات إلى أن الوضع المحايد لعنق الديبلودوكس كان قريبًا من الأفقي، وليس الرأسي، وقد استخدم علماء مثل كنت ستيفنز هذا ليقولوا إن الصوروثودات بما في ذلك الديبلودوكس كان لا ترفع رؤوسها فوق مستوى الكتف.[72][73]

قد يكون الرباط القفوي قد ثبت العنق في هذا الوضع.[72] وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 2009 أن قاعدة عنق جميع رباعيات الأرجل بوضعية رأسية قصوى تمكنها من مد عنقها عندما تكون في وضع طبيعي، وفي حالة تأهب، وجادل بأن الشيء نفسه ينطبق على الصرپوديات باستثناء أي خصائص غير معروفة وفريدة من نوعها تحدد تشريح الأنسجة الرخوة لأعناقهم بعيدًا عن الحيوانات الأخرى. وجدت الدراسة عيوبًا في افتراضات ستيفنز فيما يتعلق بالنطاق المحتمل للحركة في أعناق السوروبود ، واستنادًا إلى مقارنة الهياكل العظمية بالحيوانات الحية، جادلت الدراسة أيضًا أن الأنسجة الرخوة يمكن أن تزيد المرونة أكثر مما تقترحه العظام وحدها. لهذه الأسباب جادلوا بأن "الديبلودوكس" كان من شأنه أن يرفع رقبته بزاوية مرتفعة أكثر مما خلصت إليه الدراسات السابقة.[74]

كما هو الحال مع جنس "الباروصورات" ذي الصلة، فإن العنق الطويل جدًا "للديبلودوكس" هو مصدر الكثير من الجدل بين العلماء. أشارت دراسة أجريت في جامعة كولومبيا عام 1992 حول بنية عنق الديبلودوكسات إلى أن أطول عنق كانت تتطلب قلبًا يبلغ وزنه 1.6 طن - أي عُشر وزن جسم الحيوان. اقترحت الدراسة أن حيوانات مثل هذه كان لديها "قلوب" مساعدة بدائية في أعناقها، والغرض الوحيد منها هو ضخ الدم إلى "القلب" التالي.[8] يجادل البعض بأن الوضع شبه الأفقي للرأس والعنق كان سيقضي على مشكلة إمداد المخ بالدم، لأنه لن يُرفع.[25]

التغذية والنظام الغذائي

تمتلك الديبلودوكس أسنان غير عادية للغاية مقارنة بالصرپوديات الأخرى. التيجان طويلة ونحيلة، وبيضاوية الشكل في المقطع العرضي، بينما تشكل القمة نقطة حادة مثلثة الشكل. يظهر وجه التآكل الأكثر بروزًا على القمة، على الرغم من أنه على عكس جميع أنماط التآكل الأخرى التي لوحظت داخل الصرپوديات، فإن أنماط التآكل ثنائية الطبقة موجودة على الجانب الشفوي (الخد) لكل من الأسنان العلوية والسفلية.[24]

هذا يعني أن آلية تغذية الديبلودوكسات كانت مختلفة اختلافًا جذريًا عن تلك الخاصة بالصرپوديات الأخرى. تجريد الفروع من جانب واحد هو السلوك الغذائي الأكثر احتمالاً للديبلودوكسات،[75][76][77] لأنه يفسر أنماط التآكل غير العادية للأسنان (الناتجة عن ملامسة الأسنان مع الطعام). في تجريد الفروع من جانب واحد، كان من الممكن استخدام صف واحد من الأسنان لتجريد أوراق الشجر من الساق، بينما يعمل الآخر كدليل ومثبت. مع المنطقة المطولة قبل الحجاج (مقدمة العينين) من الجمجمة، يمكن تجريد الأجزاء الأطول من السيقان في حركة واحدة. أيضًا، يمكن أن تكون الحركة الحنكية (للخلف) للفكين السفليين قد ساهمت في دورين مهمين في سلوك التغذية: (1) زيادة فغر الفم، و(2) السماح بإجراء تعديلات دقيقة على المواضع النسبية لصفوف الأسنان، مما يخلق حركة تجريد سلسة.[24]

استخدم يونگ وزملائه (2012) النمذجة الميكانيكية الحيوية لفحص أداء جمجمة الديبلودوكس. وخلص إلى أن الاقتراح القائل بأن الديبلودوكسات كانت تستخدم أسنانها في تجريد اللحاء لم يكن مدعومًا بالبيانات، والتي أظهرت أنه في ظل هذا السيناريو، ستخضع الجمجمة والأسنان لضغوط شديدة. أثبت فرضيات تجريد الفروع و/أو العض الدقيق على حد سواء على أنها سلوكيات تغذية مقبولة من الناحية الميكانيكية الحيوية.[78] كما كانت أيضًا الديبلودوكسات تستبدل أسنانها باستمرار طوال حياتها، عادةً في أقل من 35 يومًا، كما اكتشف مايكل ديميك وزملائه. تكشف الدراسات التي أجريت على الأسنان أيضًا أن الديبلودوكسات كانت تفضل نباتات مختلفة عن الصرپوديات الأخرى في تكوين موريسون، مثل "الكاماراصورات". قد يكون هذا قد سمح بشكل أفضل لأنواع مختلفة من الصرپوديات بالوجود دون منافسة.[79]

نوقشت مرونة عنق الديبلودوكسات لكن كان من المفترض أنها كانت قادرة على الرعي من المستويات المنخفضة إلى حوالي 4 أمتار عندما تكون على أربع.[25][72] إلا أن الدراسات قد أظهرت أن الديبلودوكسات كانت قريبة للغاية من مركز كتلة حُقّ الورك؛[80][81] مما يعني أن الديبلودوكس كانت نادراً ما تتخذ وضعية الوقوف على قدمين بجهد قليل نسبياً. كما أنها تتمتع بميزة استخدام ذيلها الكبير كدعامة الذي من شأنه أن يسمح بوضعية ثلاثية الأرجل ثابتة للغاية. في وضع ثلاثي الأرجل، يمكن للديبلودوكس الرعي على مارتفاع أكبر حتى حوالي 11 متر.[81][82]

كان نطاق حركة العنق يسمح أيضًا للرأس بالرعي تحت مستوى الجسم، مما دفع بعض العلماء للتكهن فيما إذا كانت الديبلودوكسات ترعى على نباتات مائية مغمورة من ضفاف الأنهار. يدعم مفهوم وضع التغذية هذا من خلال الأطوال النسبية للأطراف الأمامية والخلفية. علاوة على ذلك، ربما كانت الديبلودوكسات تستخدم أسنانها الشبيهة بالوتد لأكل نباتات الماء اللينة.[72] عارض ماثيو كوبلي وزملائه (2013) ذلك، ووجد أن العضلات الكبيرة والغضاريف ستحد من حركة الرقبة. وذكر أن نطاقات تغذية الصرپوديات مثل الديبلودوكسات كانت أضيق مما كان يعتقد سابقًا، وربما اضطرت الحيوانات إلى تحريك أجسادها بالكامل للوصول بشكل أفضل إلى المناطق التي يمكنهم فيها رعي النباتات. على هذا النحو، ربما قضوا وقتًا أطول في البحث عن الطعام لتلبية الحد الأدنى من احتياجاتهم من الطاقة.[83][84] استنتاجات كوبلي وزملائه عامي 2013 و2014 جادل فيها مايك تيلور، الذي قام بتحليل كمية وموضع الغضروف الفقري لتحديد مرونة عنق الديبلودوكسات والأباتوصوروات. وجد تايلور أن عنق الديبلودوكس كان مرنًا للغاية، وأن استنتاج كوبلي وزملائه كان غير صحيح، حيث أن المرونة التي تدل عليها العظام أقل مما هي عليه في الواقع.[85]

عام 2010، وصف وايتلوك وآخرون جمجمة الديبلودوكسات الصغار في ذلك الوقت المشار إليها باسم (CM & nbsp؛ 11255) التي تختلف اختلافًا كبيرًا عن الجماجم البالغة من نفس الجنس: فمها لم يكن حادًا، والأسنان لم تكن محصورة في مقدمة الخطم. تشير هذه الاختلافات إلى أن الديبلودوكسات البالغة والصغيرة كانت تتغذى بشكل مختلف. لم يلاحظ مثل هذا الاختلاف البيئي بين البالغين والأحداث سابقًا في أشباه الصوروپودات.[86]

التكاثر والنمو

في حين تم تفسير العنق الطويل تقليديًا على أنه تكيف للتغذية، فقد اقترح أيضاً[87] حجم العنق الضخم للديبلودوكسات والأنواع القريبة يكون عرضًا جنسيًا في المقام الأول، وأن أهميته في التغذية تكون في المقام الثاني. دحضت دراسة عام 2011 هذه الفكرة بالتفصيل.[88]

بينما لا يوجد دليل يشير إلى عادات التعشيش لدى الديبلودوكسات، فإن الصرپوديات الأخرى، مثل التيتانوصور "سالتوصور، قد ارتبطت بمواقع التعشيش.[89][90] تشير مواقع أعشاش التيتانوصور إلى أنها ربما وضعت بيضها بشكل جماعي على مساحة كبيرة في العديد من الحفر الضحلة، كل منها مغطى بالنباتات. ربما فعلت الديبلودوكسات الشيء نفسه. صور الفيلم الوثائقي "المشي مع الديناصورات" الأم "الديبلودوكس" تستخدم المسرأ لوضع البيض، لكنها كانت مجرد تكهنات من جانب مؤلف الفيلم الوثائقي.[28] بالنسبة للديبلودوكسات والصوروپودات الأخرى، فإن the size of clutches and individual eggs were surprisingly small for such large animals. This appears to have been an adaptation to predation pressures, as large eggs would require greater incubation time and thus would be at greater risk.[91]

Based on a number of bone histology studies, Diplodocus, along with other sauropods, grew at a very fast rate, reaching sexual maturity at just over a decade, and continuing to grow throughout their lives.[92][93][94]

علم البيئة العتيقة

تكوين موريسون عبارة عن سلسلة من الرواسب البحرية الضحلة والرواسب الغرينية، بحسب التأريخ الإشعاعي، يتراوح عمرها بين 156.3 مليون سنة عند قاعدتها،[95] و146.8 مليون سنة عند القمة،[96] مما يضعها في أواخر المرحلة الأكسفوردية، الكيمريدجية، وأوائل التيثونية في العصر الطباشيري المتأخر. يفشر هذا التكوين على أنه بيئة شبه قاحلة بموسمين رطب وجاف متميزين. حوض موريسون، حيث كانت تعيش العديد من الديناصورات، يمتد من نيو مكسيكو إلى ألبرتا وسسكاتشوان، وتشكل عندما بدأت طلائع السلسلة الأمامية لجبال روكي في الاندفاع غرباً. انتقلت الرواسب من أحواض التصريف المواجهة للشرق عن طريق الجداول والأنهار وترسبت في أراضي المستنقعات المنخفضة والبحيرات وقنوات الأنهار والسهول الفيضية.[97]

يشبه هذا التكوين في العمر تكوين لورينها في الپرتغال وتكوين تنداگورو في تنزانيا.[98]

يسجل تكوين موريسون بيئة وزمناً كانت تهيمن عليهما الديناصورات الصورپودية العملاقة.[99] الديناصورات المعروفة من تكوين موريسون تتضمن الديناصورات الوحش قدمية التالية: السيراتوصورات، الكوپاريونات، الستوكصورات، الأوريثولستات، الألوصورات، والتورڤوصورات، الديناصورات الصوروپودية التالية: الأپاتوصورات، البراكيوصورات، الكاماراصورات، والديپلودوكسات، والديناصورات الوركية الطائرة: الكامپتوصورات، الدريوصورات، الأوثنيليات، الگارگويليوصورات، والستگيوصورات.[100] Diplodocus is commonly found at the same sites as Apatosaurus, Allosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Stegosaurus.[101] تمثل الألوصورات 70 -75% من عينات الصوروپودات وكانت على حافة الشبكة الغذائية لتكوين موريسون.[102]

العديد من الديناصورات في تكوين موريسون هي نفس الأجناس التي شوهدت في الصخور الپرتغالية من تكوين لورينها (بشكل رئيسي الألوصورات، الكيراتوصورات، التوروڤوصورات، والستيوگوصورات)، أو نظيرة قريبة لها (البراكيوصوروات، اللوسوتيتانات، الكامپتوصورات، والدراكونيكسات).[98] تضم الفقاريات الأخرى التي تشترك في نفس البيئة القديمة الأسماك شعاعية الزعانف، الضفادع، السلمندر، السلاحف مثل Dorsetochelys ومنقارية الرأس، السحالي البرية والمائية شبيهة التماسيح مثل هوپلوسوكوس، والعديد من أنواع التيروصورات مثل Harpactognathus وMesadactylus. تعتبر أصداف ذوات المصراعين والحلزونات المائية شائعة أيضًا. كانت الحياة النباتية في تلك الفترة تتضمن الطحالب الخضراء، الفطريات، الطحالب، ذنب الحصان، السيكاسية، الجنكة، والعديد من العائلات الصنوبرية. تنوعت النباتات من الغابات المبطنة للأنهار على شكل أشجار السرخس والسرخس (غابة رواقية)، إلى ساڤنا السرخس مع الأشجار الرواقية مثل 'الأراوكاريا".[103]

الأهمية الثقافية

كان ديپلودوكس ديناصوراً شهيراً وتم تصويره كثيرًا حيث كان من أكثر الديناصورات الصوروپودية عرضاً.[104] ربما يرجع الكثير من هذا إلى وفرة بقايا الهياكل العظمية ووضعه السابق كأطول ديناصور. التبرع بالعديد من القوالب الهيكلية المركبة للديناصور "ديبي" من قبل الصناعي أندرو كارنگى للحكام في جميع أنحاء العالم في بداية القرن العشرين[105] ساهم بشكل كبير في تعريف الناس في جميع أنحاء العالم بالديناصور. لا تزال قوالب الهيكل العظمي للديناصور ديپلودوكس معروضة في العديد من المتاحف في جميع أنحاء العالم، بما في ذلك، د. كارنگى، في عدد من المؤسسات.[67]

جذب المشروع ، إلى جانب ارتباطه بـ"العلم الكبير"، الأعمال الخيرية والرأسمالية، اهتمامًا عامًا كبيرًا في أوروپا. خصصت مجلة "Kladderadatsch" الأسبوعية الساخرة الألمانية قصيدة للديناصور:

|

|

أصبح "لو ديپيلودوكس" اسماً عاماً للصوروپودات باللغة الفرنسية، كما هو الحال مع "البرونتوصور" في الإنگليزية.[107]

هناك "د. لونگوس" معروض في متحف سنكنبرگ بمدينة فرانكفورت الألمانية (هيكل عظمي مكون من عدة عينات، تم التبرع به عام 1907 من قبل المتحف الأمريكي للتاريخ الطبيعي)، ألمانيا.[108][109] وهناك هيكل عظمي أكثر اكتمالاً للديناصور "د. لونگوس" معروض في المتحف الوطني للتاريخ الطبيع في واشنطن دي سي،[110] بينما هناك هيكل عظمي للديناصور "د. هالوروم" ("سيسموصور" سابقاً)، والذي قد يكون مماثلاً للديناصور "د. لونگوس"، معروضة في متحف نيومكسيكو للتاريخ الطبيعي والعلوم.[111]

عام 1915 تم تصميم آلة حربية (مركبة أرضية) من الحرب العالمية الأولى تسمى آلة بوارلوت، واعتبرت لاحقًا غير عملية ومن ثم أطلق عليها لقب "ديپلودوكس ميليتاريس".[112]

المصادر

- ^ Ulrich Merkl (November 25, 2015). Dinomania: The Lost Art of Winsor McCay, The Secret Origins of King Kong, and the Urge to Destroy New York. Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 978-1-60699-840-3.

Although it narrowly failed to win the race with the New York Museum of Natural History in 1905, the Diplodocus carnegii is the most famous dinosaur skeleton today, due to the large number of casts in museums around the world

- ^ Breithaupt, Brent H, The discovery and loss of the “colossal” Brontosaurus giganteus from the fossil fields of Wyoming (USA) and the events that led to the discovery of Diplodocus carnegii: the first mounted dinosaur on the Iberian Peninsula, VI Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y su Entorno, September 5–7, 2013, p.49: "“Dippy" was and still is the most widely seen and best-known dinosaur ever found."

- ^ أ ب ت Simpson, John; Edmund Weiner, eds. (1989). The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8.

- ^ أ ب Pickett, Joseph P., ed. (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

- ^ "diplodocus". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O. V.; Benson, R. B. J. (2015). "A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". PeerJ. 3: e857. doi:10.7717/peerj.857. PMC 4393826. PMID 25870766.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Turner, C.E.; Peterson, F. (2004). "Reconstruction of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation extinct ecosystem—a synthesis" (PDF). Sedimentary Geology. 167 (3–4): 309–355. Bibcode:2004SedG..167..309T. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.01.009.

- ^ أ ب ت Lambert D. (1993). The Ultimate Dinosaur Book. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86438-417-1.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Paul, Gregory S. (2016). Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs: 2nd Edition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- ^ أ ب ت Molina-Perez & Larramendi (2020). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 257. Bibcode:2020dffs.book.....M.

- ^ Foster, J.R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science:Albuquerque, New Mexico. Bulletin 23.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr.; Rey, Luis V. (2011). Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages (Winter 2011 appendix). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ^ أ ب ت Gillette, D.D., 1994, Seismosaurus: The Earth Shaker. New York, Columbia University Press, 205 pp

- ^ أ ب Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus." In Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 131–138.

- ^ Herne, Matthew C.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2006). "Seismosaurus hallorum: Osteological reconstruction from the holotype". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36.

- ^ "The biggest of the big". Skeletaldrawing.com. June 14, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ Wedel, M.J. and Cifelli, R.L. Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's Native Giant. 2005. Oklahoma Geology Notes 65:2.

- ^ أ ب Wilson JA (2005). "Overview of Sauropod Phylogeny and Evolution". In Rogers KA, Wilson JA (eds.). The Sauropods:Evolution and Paleobiology. Indiana University Press. pp. 15–49. ISBN 978-0-520-24623-2.

- ^ Holland WJ (1915). "Heads and Tails: a few notes relating to the structure of sauropod dinosaurs". Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 9 (3–4): 273–278. doi:10.5962/p.331052. S2CID 251489931.

- ^ Myhrvold NP, Currie PJ (1997). "Supersonic sauropods? Tail dynamics in the diplodocids" (PDF). Paleobiology. 23 (4): 393–409. Bibcode:1997Pbio...23..393M. doi:10.1017/s0094837300019801. S2CID 83696153.

- ^ Baron, Matthew G. (October 3, 2021). "Tactile tails: a new hypothesis for the function of the elongate tails of diplodocid sauropods". Historical Biology. 33 (10): 2057–2066. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1769092. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 219762797.

- ^ أ ب Benton, Michael J. (2012). Prehistoric Life. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- ^ Bonnan, M. F. (2003). "The evolution of manus shape in sauropod dinosaurs: implications for functional morphology, forelimb orientation, and phylogeny" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (3): 595–613. Bibcode:2003JVPal..23..595B. doi:10.1671/A1108. S2CID 85667519.

- ^ أ ب ت Upchurch, P.; Barrett, P.M. (2000). "The evolution of sauropod feeding mechanism". In Sues, Hans Dieter (ed.). Evolution of Herbivory in Terrestrial Vertebrates. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59449-3.

- ^ أ ب ت Stevens, K.A.; Parrish, J.M. (1999). "Neck posture and feeding habits of two Jurassic sauropod dinosaurs". Science. 284 (5415): 798–800. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..798S. doi:10.1126/science.284.5415.798. PMID 10221910.

- ^ أ ب Czerkas, S. A. (1993). "Discovery of dermal spines reveals a new look for sauropod dinosaurs". Geology. 20 (12): 1068–1070. Bibcode:1992Geo....20.1068C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1992)020<1068:dodsra>2.3.co;2.

- ^ Czerkas, S. A. (1994). "The history and interpretation of sauropod skin impressions." In Aspects of Sauropod Paleobiology (M. G. Lockley, V. F. dos Santos, C. A. Meyer, and A. P. Hunt, Eds.), Gaia No. 10. (Lisbon, Portugal).

- ^ أ ب Haines, T., James, J. Time of the Titans Archived أكتوبر 31, 2013 at the Wayback Machine. ABC Online.

- ^ Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O. V. (2012). "The skull and neck of a new flagellicaudatan sauropod from the Morrison Formation and its implication for the evolution and ontogeny of diplodocid dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (7): 1. doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.746589. hdl:2318/1525401. S2CID 59581535.

- ^ أ ب Gallagher, T; Poole, J; Schein, J (2021). "Evidence of integumentary scale diversity in the late Jurassic Sauropod Diplodocus sp. from the Mother's Day Quarry, Montana". PeerJ. 9: e11202. doi:10.7717/peerj.11202. PMC 8098675. PMID 33986987.

- ^ Marsh OC (1878). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part I". American Journal of Science. 3 (95): 411–416. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-16.95.411. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107172876. S2CID 219245525.

- ^ أ ب ت Brinkman, P. D. (2010). The second Jurassic dinosaur rush. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ أ ب Osborn, H. F. (1899). A skeleton of Diplodocus, recently mounted in the American Museum. Science, 10(259), 870-874.

- ^ أ ب Upchurch P, Barrett PM, Dodson P (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ أ ب ت Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O. (2016). "Diplodocus Marsh, 1878 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda): proposed designation of D. carnegii Hatcher, 1901 as the type species". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 73 (1): 17–24. doi:10.21805/bzn.v73i1.a22. S2CID 89131617.

- ^ أ ب ICZN. (2018). "Opinion 2425 (Case 3700) – Diplodocus Marsh, 1878 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda): Diplodocus longus Marsh, 1878 maintained as the type species". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 75 (1): 285–287. doi:10.21805/bzn.v75.a062. S2CID 92845326.

- ^ أ ب ت Marsh, O.C. (1884). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part VII. On the Diplodocidae, a new family of the Sauropoda". American Journal of Science. 3 (158): 160–168. Bibcode:1884AmJS...27..161M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-27.158.161. S2CID 130293109.

- ^ McIntosh, J. S., & Carpenter, K. (1998). THE HOLOTYPE OF DIPLODOCUS LONGUS, WITH COMMENTS ON OTHER SPECIMENS. Modern Geology, 23, 85-110.

- ^ Marsh, O. C. (1896). The dinosaurs of North America. US Government Printing Office.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Hatcher, J. B. (1901). Diplodocus (Marsh): its osteology, taxonomy, and probable habits, with a restoration of the skeleton (Vol. 1, No. 1-4). Carnegie institute.

- ^ Tschopp, Emanuel; Mateus, Octávio (May 2, 2017). "Osteology of Galeamopus pabsti sp. nov. (Sauropoda: Diplodocidae), with implications for neurocentral closure timing, and the cervico-dorsal transition in diplodocids". PeerJ (in الإنجليزية). 5: e3179. doi:10.7717/peerj.3179. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5417106. PMID 28480132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ أ ب Otero, Alejandro; Gasparini, Zulma (2014). "The History of the Cast Skeleton of Diplodocus carnegii Hatcher, 1901, at the Museo De La Plata, Argentina". Annals of Carnegie Museum (in الإنجليزية). 82 (3): 291–304. doi:10.2992/007.082.0301. ISSN 0097-4463. S2CID 86199772.

- ^ McCall, Chris (January 22, 2019). "Dippy, 'the UK's most famous dinosaur', arrives at Kelvingrove Museum". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Holland WJ. (1924) The skull of Diplodocus. Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum IX; 379–403.

- ^ Whitlock, John A.; Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Lamanna, Matthew C. (March 24, 2010). "Description of a nearly complete juvenile skull of Diplodocus (Sauropoda: Diplodocoidea) from the Late Jurassic of North America" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (2): 442–457. Bibcode:2010JVPal..30..442W. doi:10.1080/02724631003617647. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 84498336.

- ^ Gilmore, Charles W. (1932). "On a newly mounted skeleton of Diplodocus in the United States National Museum" (PDF). Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 81 (2941): 1–21. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.81-2941.1. ISSN 0096-3801.

- ^ أ ب Schein, J. P., Poole, J. C., Schmidt, R. W., & Rooney, L. (2019). Reopening the Mother’s Day Quarry (Jurassic Morrison Formation, Montana) is yielding new information. In Geological Society of America–Annual Meeting, Arizona (pp. 22-25).

- ^ Woodruff, D. C., Carr, T. D., Storrs, G. W., Waskow, K., Scannella, J. B., Nordén, K. K., & Wilson, J. P. (2018). The smallest diplodocid skull reveals cranial ontogeny and growth-related dietary changes in the largest dinosaurs. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1-12.

- ^ أ ب Taylor, M.P.; Naish, D. (2005). "The phylogenetic taxonomy of Diplodocoidea (Dinosauria: Sauropoda)". PaleoBios. 25 (2): 1–7. ISSN 0031-0298.

- ^ أ ب Harris, J.D. (2006). "The significance of Suuwassea emiliae (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) for flagellicaudatan intrarelationships and evolution". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001805. S2CID 9646734.

- ^ Bonaparte, J.F.; Mateus, O. (1999). "A new diplodocid, Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis gen. et sp. nov., from the Late Jurassic beds of Portugal". Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 5 (2): 13–29. Archived from the original on 19 فبراير 2012. Retrieved 13 يونيو 2013.

- ^ أ ب Rauhut, O.W.M.; Remes, K.; Fechner, R.; Cladera, G.; Puerta, P. (2005). "Discovery of a short-necked sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period of Patagonia". Nature. 435 (7042): 670–672. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..670R. doi:10.1038/nature03623. PMID 15931221. S2CID 4385136.

- ^ أ ب Wilson, J. A. (2002). "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistica analysis". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 136 (2): 217–276. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x.

- ^ أ ب Upchurch P, Barrett PM, Dodson P (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Brezinski, D. K.; Kollar, A. D. (2008). "Geology of the Carnegie Museum Dinosaur Quarry Site of Diplodocus carnegii, Sheep Creek, Wyoming". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 77 (2): 243–252. doi:10.2992/0097-4463-77.2.243. S2CID 129474414.

- ^ Gillette, D.D. (1991). "Seismosaurus halli, gen. et sp. nov., a new sauropod dinosaur from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous) of New Mexico, USA". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (4): 417–433. Bibcode:1991JVPal..11..417G. doi:10.1080/02724634.1991.10011413.

- ^ "Hall, Jim & Ruth". sflivingtreasures.org.

- ^ Lucas S, Herne M, Heckert A, Hunt A, and Sullivan R. Reappraisal of Seismosaurus, A Late Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaur from New Mexico. Archived أكتوبر 8, 2019 at the Wayback Machine The Geological Society of America, 2004 Denver Annual Meeting (November 7–10, 2004). Retrieved on May 24, 2007.

- ^ Lucas, S.G.; Spielman, J.A.; Rinehart, L.A.; Heckert, A.B.; Herne, M.C.; Hunt, A.P.; Foster, J.R.; Sullivan, R.M. (2006). "Taxonomic status of Seismosaurus hallorum, a Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaur from New Mexico". In Foster, J.R.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (bulletin 36). pp. 149–161. ISSN 1524-4156.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional. 65 (4): 527–544.

- ^ Mortimer, Mickey (March 2017). "Comment (Case 3700) — A statement against the proposed designation of Diplodocus carnegii Hatcher, 1901 as the type species of Diplodocus Marsh, 1878 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 73 (2–4): 129–131. doi:10.21805/bzn.v73i2.a14. eISSN 2057-0570. ISSN 0007-5167. S2CID 89861495.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (May 15, 2017). "Comment (Case 3700) — Opposition against the proposed designation of Diplodocus carnegii Hatcher, 1901 as the type species of Diplodocus Marsh, 1878 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 74 (1): 47–49. doi:10.21805/bzn.v74.a014. eISSN 2057-0570. ISSN 0007-5167. S2CID 89682495.

- ^ Upchurch, P.; Barrett, P.M.; Dodson, P. (2004). "Sauropoda". In D. B. Weishampel; P. Dodson; H. Osmólska (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. pp. 259–322. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4.

- ^ Mossbrucker, M. T., & Bakker, R. T. (October 2013). Missing muzzle found: new skull material referrable to Apatosaurus ajax (Marsh 1877) from the Morrison Formation of Morrison, Colorado. In Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs (Vol. 45, p. 111).

- ^ Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–8. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..705S. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820. S2CID 33253407.

- ^ Kermack, Kenneth A. (1951). "A note on the habits of sauropods". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 12 (4): 830–832. doi:10.1080/00222935108654213.

- ^ أ ب ت Gangewere, J.R. (1999). "Diplodocus carnegii Archived 12 يناير 2012 at the Wayback Machine". Carnegie Magazine.

- ^ Pierson, D. J. (2009). "The Physiology of Dinosaurs: Circulatory and Respiratory Function in the Largest Animals Ever to Walk the Earth". Respiratory Care. 54 (7): 887–911. doi:10.4187/002013209793800286. PMID 19558740.

- ^ Hay, O. P., 1910, Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences, vol. 12,, pp. 1–25

- ^ Hay, Dr. Oliver P., "On the Habits and Pose of the Sauropod Dinosaurs, especially of Diplodocus." The American Naturalist, Vol. XLII, October 1908

- ^ Holland, Dr. W. J. (1910). "A Review of Some Recent Criticisms of the Restorations of Sauropod Dinosaurs Existing in the Museums of the United States, with Special Reference to that of Diplodocus carnegii in the Carnegie Museum". The American Naturalist. 44 (521): 259–283. doi:10.1086/279138. S2CID 84424110.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Stevens KA, Parrish JM (2005). "Neck Posture, Dentition and Feeding Strategies in Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaurs". In Carpenter, Kenneth, Tidswell, Virginia (eds.). Thunder Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 212–232. ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.

- ^ Upchurch, P; et al. (2000). "Neck Posture of Sauropod Dinosaurs" (PDF). Science. 287 (5453): 547b. doi:10.1126/science.287.5453.547b. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- ^ Taylor, M.P.; Wedel, M.J.; Naish, D. (2009). "Head and neck posture in sauropod dinosaurs inferred from extant animals" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 54 (2): 213–220. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0007. S2CID 7582320.

- ^ Norman, D.B. (1985). The illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. London: Salamander Books Ltd

- ^ Dodson, P. (1990). "Sauropod paleoecology". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria" 1st Edition. University of California Press. ASIN B008UBRHZM.

- ^ Barrett, P.M.; Upchurch, P. (1994). "Feeding mechanisms of Diplodocus". Gaia. 10: 195–204.

- ^ Young, Mark T.; Rayfield, Emily J.; Holliday, Casey M.; Witmer, Lawrence M.; Button, David J.; Upchurch, Paul; Barrett, Paul M. (August 2012). "Cranial biomechanics of Diplodocus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda): testing hypotheses of feeding behavior in an extinct megaherbivore". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (8): 637–643. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..637Y. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0944-y. ISSN 1432-1904. PMID 22790834. S2CID 15109500.

- ^ D’Emic, M. D.; Whitlock, J. A.; Smith, K. M.; Fisher, D. C.; Wilson, J. A. (2013). Evans, A. R. (ed.). "Evolution of high tooth replacement rates in sauropod dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69235. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869235D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069235. PMC 3714237. PMID 23874921.

- ^ Henderson, Donald M. (2006). "Burly gaits: centers of mass, stability, and the trackways of sauropod dinosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 907–921. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[907:BGCOMS]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86216852.

- ^ أ ب Mallison, H. (2011). "Rearing Giants – kinetic-dynamic modeling of sauropod bipedal and tripodal poses". In Farlow, J.; Klein, N.; Remes, K.; Gee, C.; Snader, M. (eds.). Biology of the Sauropod Dinosaurs: Understanding the life of giants. Life of the Past. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35508-9.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2017). "Restoring Maximum Vertical Browsing Reach in Sauropod Dinosaurs". The Anatomical Record. 300 (10): 1802–1825. doi:10.1002/ar.23617. PMID 28556505.

- ^ Cobley, Matthew J.; Rayfield, Emily J.; Barrett, Paul M. (2013). "Inter-Vertebral Flexibility of the Ostrich Neck: Implications for Estimating Sauropod Neck Flexibility". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e72187. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872187C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072187. PMC 3743800. PMID 23967284.

- ^ Ghose, Tia (August 15, 2013). "Ouch! Long-Necked Dinosaurs Had Stiff Necks". livescience.com. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Taylor, M.P. (2014). "Quantifying the effect of intervertebral cartilage on neutral posture in the necks of sauropod dinosaurs". PeerJ. 2: e712. doi:10.7717/peerj.712. PMC 4277489. PMID 25551027.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Whitlock, John A.; Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Lamanna, Matthew C. (March 2010). "Description of a Nearly Complete Juvenile Skull of Diplodocus (Sauropoda: Diplodocoidea) from the Late Jurassic of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (2): 442–457. Bibcode:2010JVPal..30..442W. doi:10.1080/02724631003617647. S2CID 84498336.

- ^ Senter, P. (2006). "Necks for Sex: Sexual Selection as an Explanation for Sauropod Neck Elongation" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 271 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00197.x.

- ^ Taylor, M.P.; Hone, D.W.E.; Wedel, M.J.; Naish, D. (2011). "The long necks of sauropods did not evolve primarily through sexual selection" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 285 (2): 151–160. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00824.x.

- ^ Walking on Eggs: The Astonishing Discovery of Thousands of Dinosaur Eggs in the Badlands of Patagonia, by Luis Chiappe and Lowell Dingus. June 19, 2001, Scribner

- ^ Grellet-Tinner, Chiappe Coria (2004). "Eggs of titanosaurid sauropods from the Upper Cretaceous of Auca Mahuevo (Argentina)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 41 (8): 949–960. Bibcode:2004CaJES..41..949G. doi:10.1139/e04-049.

- ^ Ruxton, Graeme D.; Birchard, Geoffrey F.; Deeming, D Charles (2014). "Incubation time as an important influence on egg production and distribution into clutches for sauropod dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 40 (3): 323–330. Bibcode:2014Pbio...40..323R. doi:10.1666/13028. S2CID 84437615.

- ^ Sander, P. M. (2000). "Long bone histology of the Tendaguru sauropods: Implications for growth and biology" (PDF). Paleobiology. 26 (3): 466–488. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0466:lhotts>2.0.co;2. JSTOR 2666121. S2CID 86183725.

- ^ Sander, P. M.; N. Klein; E. Buffetaut; G. Cuny; V. Suteethorn; J. Le Loeuff (2004). "Adaptive radiation in sauropod dinosaurs: Bone histology indicates rapid evolution of giant body size through acceleration" (PDF). Organisms, Diversity & Evolution. 4 (3): 165–173. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2003.12.002.

- ^ Sander, P. M.; N. Klein (2005). "Developmental plasticity in the life history of a prosauropod dinosaur". Science. 310 (5755): 1800–1802. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1800S. doi:10.1126/science.1120125. PMID 16357257. S2CID 19132660.

- ^ Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

- ^ Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry – age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; Kirkland, J.I. (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- ^ Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- ^ أ ب Mateus, Octávio (2006). "Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation (USA), the Lourinhã and Alcobaça Formations (Portugal), and the Tendaguru Beds (Tanzania): A comparison". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 223–231.

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329.

- ^ Chure, Daniel J.; Litwin, Ron; Hasiotis, Stephen T.; Evanoff, Emmett; Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 233–248.

- ^ Dodson, P.; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Bakker, R.T.; McIntosh, J.S. (1980). "Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation". Paleobiology. 6 (1): 208–232. doi:10.1017/S0094837300025768. JSTOR 240035.

- ^ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

- ^ "Diplodocus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 58–59. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ^ Rea, Tom (2001). Bone Wars. The Excavation and Celebrity of Andrew Carnegie's Dinosaur. Pittsburgh University Press. See particularly pages 1–11 and 198–216.

- ^ "Die Wanderjahre". Kladderadatsch (in الألمانية). Vol. 61. May 10, 1908. p. 319.

- ^ Russell, Dale A. (1988). An Odyssey in Time: the Dinosaurs of North America. NorthWord Press, Minocqua, WI. p. 76.

- ^ Sachs, Sven (2001). "Diplodocus – Ein Sauropode aus dem Oberen Jura (Morrison-Formation) Nordamerikas". Natur und Museum. 131 (5): 133–150.

- ^ Beasley, Walter (1907). "An American Dinosaur for Germany." The World Today, August 1907: 846–849.

- ^ "Dinosaur Collections". National Museum of Natural History. 2008.

- ^ "Age of Giants Hall Archived 1 نوفمبر 2013 at the Wayback Machine". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

- ^ Czech article about Boirault machine ("Diplodocus militaris")

وصلات خارجية

- Diplodocus in the Dino Directory

- Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid

- Diplodocus Marsh, by J.B. Hatcher 1901 – Its Osteology, Taxonomy, and Probable Habits, with a Restoration of the Skeleton. Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, Volume 1, Number 1, 1901. Full text, Free to read.

- Skeletal restorations of diplodocids including D. carnegii, D. longus, and D. hallorum, from Scott Hartman's Skeletal Drawing website.

- CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- مقالات مميزة

- ديبلودوكس

- ديناصورات تكوين موريسون

- ديناصورات العصر الطباشيري المتأخر في أمريكا الشمالية

- أندرو كارنگى

- أصنوفات أحفورات وصفت في 1878

- أصنوفات سماها أوثنيال تشارلز مارش

- علم الإحاثة في كلورادو

- علم الإحاثة في يوتا

- علم الإحاثة مونتانا

- علم الإحاثة في وايومنگ