سكرانتون، پنسلڤانيا

سكرانتون، پنسلڤانيا

Scranton, Pennsylvania | |

|---|---|

| مدينة سكرانتون | |

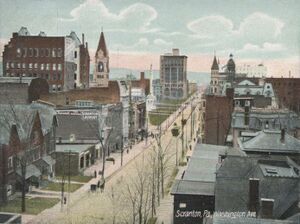

وسط سكرانتون Courthouse Square | |

| الكنية: The Electric City, The All America City, Steamtown, The Coal Capital | |

| الشعار: Embracing Our People, Our Traditions and Our Future | |

| |

| الإحداثيات: 41°24′38″N 75°40′03″W / 41.41056°N 75.66750°W | |

| البلد | |

| الولاية | |

| المقاطعة | لاكاوانا |

| المنطقة | سكرانتون الكبرى |

| Incorporated (borough) | February 14, 1856 |

| Incorporated (city) | April 23, 1866 |

| السمِيْ | جورج سكرانتون |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة | Paige Gebhardt Cognetti |

| المساحة | |

| • مدينة | 25٫54 ميل² (66٫14 كم²) |

| • البر | 25٫31 ميل² (65٫55 كم²) |

| • الماء | 0٫23 ميل² (0٫60 كم²) |

| • العمران | 1٬777 ميل² (4٬602 كم²) |

| المنسوب | 745 ft (227 m) |

| التعداد | |

| • مدينة | 76٬089 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 76٬653 |

| • الكثافة | 3٬028٫81/sq mi (1٬169٫45/km2) |

| • Urban | 381٬502 (US: 99th) |

| • العمرانية | 562٬037 (US: 95th) |

| صفة المواطن | Scrantonian |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 18447, 18501–18505, 18507–18510, 18512, 18514–18515, 18517–18519, 18522, 18540, 18577 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 570 and 272 |

| FIPS code | 42-69000 |

| Primary Airport | Wilkes-Barre/Scranton International Airport (AVP; Major/International) |

| Secondary Airport | Wilkes-Barre Wyoming Valley Airport (WBW; Minor) |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

سكرانتون Scranton هي سادس أكبر مدينة في كومنولث پنسلڤانيا. وهي مقر المقاطعة وأكبر مدن مقاطعة لاكاوانا في وادي وايومنگ في شمال شرق پنسلڤانيا وتستضيف federal court building for the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania. With an estimated population in 2019 of 76,653, it is the largest city in northeastern Pennsylvania and the Scranton–Wilkes-Barre–Hazleton, PA Metropolitan Statistical Area, which has a population of about 570,000.[4] The city is conventionally divided into nine districts: North Scranton, Southside, Westside, the Hill Section, Central City, Minooka, East Mountain, Providence, and Green Ridge, though these areas do not have legal status.

Scranton is the geographic and cultural center of the Lackawanna River valley and northeastern Pennsylvania, and the largest of the former anthracite coal mining communities in a contiguous quilt-work that also includes ويلكس-بار, Nanticoke, Pittston, and Carbondale. Scranton was incorporated on February 14, 1856, as a borough in Luzerne County and as a city on April 23, 1866. It became a major industrial city, a center of mining and railroads, and attracted thousands of new immigrants. It was the site of the Scranton General Strike in 1877.

People in northern Luzerne County sought a new county in 1839, but the Wilkes-Barre area resisted losing its assets. Lackawanna County did not gain independent status until 1878. Under legislation allowing the issue to be voted by residents of the proposed territory, voters favored the new county by a proportion of 6 to 1, with Scranton residents providing the major support. The city was designated as the county seat when Lackawanna County was established in 1878, and a judicial district was authorized in July 1879.

The city's nickname "Electric City" began when electric lights were introduced in 1880 at the Dickson Manufacturing Company. Six years later, the United States' first streetcars powered only by electricity began operating in the city.[5][6] the claim is widespread, but it simply means a single line was set up as electric.[محل شك] Rev. David Spencer, a local Baptist minister, later proclaimed Scranton as the "Electric City".[7]

The city's industrial production and population peaked in the 1930s and 1940s, fueled by demand for coal and textiles, especially during World War II. But while the national economy boomed after the war, demand for the region's coal declined as other forms of energy became more popular, which also harmed the rail industry. Foreseeing the decline, city leaders formulated the Scranton Plan in 1945 to diversify the local economy beyond coal, but the city's economy continued to decline. The Knox Mine disaster of 1959 essentially ended coal mining in the region. Scranton's population dropped from its peak of 143,000 in the 1930 census to 76,000 in the 2010 census. The city now has large health care and manufacturing sectors.

التاريخ

القرن الثامن عشر

In 1778, during the colonial era, Isaac Tripp, the area's first known white settler, built his home here; it still stands in North Scranton, formerly a separate town known as Providence. More settlers from Connecticut Colony came to the area in the late 18th and early 19th centuries following the end of the American Revolutionary War, since their state claimed the area as part of their colonial charter.

They gradually established mills and other small businesses in a village that became known as Slocum Hollow. People in the village during this time carried the traits and accent of their New England settlers, which were somewhat different from most of Pennsylvania. Some area settlers from Connecticut participated in what was known as the Pennamite Wars, where settlers competed for control of the territory which had been included in royal colonial land grants to both states. The claim between Connecticut and Pennsylvania was settled by negotiation with the federal government's involvement following the Revolutionary War.

القرن التاسع عشر

Though anthracite coal was being mined in Carbondale to the north and Wilkes-Barre to the south, the industries that precipitated the city's early rapid growth were iron and steel. In the 1840s, brothers Selden T. and George W. Scranton, who had worked at Oxford Furnace in Oxford, New Jersey, founded what became Lackawanna Iron & Coal, later developing as the Lackawanna Steel Company. It initially started producing iron nails, but that venture failed due to low-quality iron. The Erie Railroad's construction in New York State was delayed by its having to acquire iron rails as imports from England. The Scrantons' firm decided to switch its focus to producing T-rails for the Erie; the company soon became a major producer of rails for the rapidly expanding railroads.

In 1851, the Scrantons built the Lackawanna and Western Railroad (L&W) northward, with recent Irish immigrants supplying most of the labor, to meet the Erie Railroad in Great Bend, Pennsylvania. Thus they could transport manufactured rails from the Lackawanna Valley to New York and the Midwest. They also invested in coal mining operations in the city to fuel their steel operations, and to market it to businesses. In 1856, they expanded the railroad eastward as the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (DL&W), in order to tap into the New York City metropolitan market. This railroad, with its hub in Scranton, was Scranton's largest employer for almost one hundred years.

The Pennsylvania Coal Company built a gravity railroad in the 1850s through the city for the purpose of transporting coal. The gravity railroad was replaced by a steam railroad built in 1886 by the Erie and Wyoming Valley Railroad (later absorbed by the Erie Railroad). The Delaware and Hudson (D&H) Canal Company, which had its own gravity railroad from Carbondale to Honesdale, built a steam railroad that entered Scranton in 1863.

During this short period of time, the city rapidly transformed from a small, agrarian-based village of people with New England roots to a multicultural, industrial-based city. From 1860 to 1900, the city's population increased more than tenfold. Most new immigrants, such as the Irish, Italians, and south Germans and Polish, were Catholic, a contrast to the majority-Protestant early settlers of colonial descent. National, ethnic, religious and class differences were wrapped into political affiliations, with many new immigrants joining the Democratic Party, and, for a time in the late 1870s, the Greenbacker-Labor Party.

In 1856, the borough of Scranton was officially incorporated. It was incorporated as a city of 35,000 in 1866 in Luzerne County, when the surrounding boroughs of Hyde Park (now part of the city's West Side) and Providence (now part of North Scranton) were merged with Scranton. Twelve years later in 1878, the state passed a law enabling creation of new counties where a county's population surpassed 150,000, as did Luzerne's. The law appeared to enable the creation of Lackawanna County, and there was considerable political agitation around the authorizing process. Scranton was designated by the state legislature as the county seat of the newly formed county, which was also established as a separate judicial district, with state judges moving over from Luzerne County after courts were organized in October 1878. This was the last county in the state to be organized.

Creation of the new county, which enabled both more local control and political patronage, helped begin the Scranton General Strike of 1877. This was in part due to the larger Great Railroad Strike, in which railroad workers began to organize and participate in walkouts after wage cuts in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The national economy had lagged since the Panic of 1873, and workers in many industries struggled with low wages and intermittent work. In Scranton, mineworkers followed the railroad men off the job, as did others. A protest of 5,000 strikers ended in violence, with a total of four men killed, and 20 to 50 injured, including the mayor. He had established a militia, but called for help from the governor and state militia. Governor John Hartranft eventually brought in federal troops to quell the strike. The workers gained nothing in wages, but began to organize more purposefully into labor unions that could wield more power.

The nation's first successful, continuously operating electrified streetcar (trolley) system was established in the city in 1886, inspiring the nickname "The Electric City". In 1896, the city's various streetcar companies were consolidated into the Scranton Railway Company, which ran trolleys until 1954. By 1890, three other railroads had built lines to tap into the rich supply of coal in and around the city, including the Erie Railroad, the Central Railroad of New Jersey and finally the New York, Ontario and Western Railway (NYO&W).

As the vast rail network spread above ground, an even larger network of railways served the rapidly expanding system of coal veins underground. Miners, who in the early years were typically Welsh and Irish, were hired as cheaply as possible by the coal barons. The workers endured low pay, long hours and unsafe working conditions. Children as young as eight or nine worked 14-hour days separating slate from coal in the breakers. Often, the workers were forced to use company-provided housing and purchase food and other goods from stores owned by the coal companies. With hundreds of thousands of immigrants arriving in the industrial cities, mine owners did not have to search for labor and workers struggled to keep their positions. Later miners came from Italy and eastern Europe, which people fled because of poverty and lack of jobs.

Business was booming at the end of the 19th century. The tonnage of coal mined increased virtually every year, as did the steel manufactured by the Lackawanna Steel Company. At one point the company had the largest steel plant in the United States, and it was still the second largest producer at the turn of the 20th century. By 1900, the city had a population of more than 100,000.

In the late 1890s, Scranton was home to a series of early International League baseball teams.

Scranton has had a notable labor history; various coal worker unions struggled throughout the coal-mining era to improve working conditions, raise wages, and guarantee fair treatment for workers.[8] The Panic of 1873 and other economic difficulties caused a national recession and loss of business. As the economy contracted, the railroad companies reduced wages of workers in most classes (while sometimes reserving raises for their top management). A major strike of railroad workers in August 1877, part of the Great Railroad Strike, attracted workers from the steel industry and mining as well, and developed as the Scranton General Strike. Four rioters were killed during unrest during the strike, after the mayor mustered a militia. With violence suppressed by militia and federal troops, workers finally returned to their jobs, not able to gain any economic relief. William Walker Scranton, from the prominent family, was then general manager of Lackawanna Iron and Coal. He later founded Scranton Steel Company.

The labor issues and growth of industry in Scranton contributed to Lackawanna County being established by the state legislature in 1878, with territory taken from Luzerne County. Scranton was designated as the county seat. This strengthened its local government.

The unions failed to gain higher wages that year, but in 1878 they elected labor leader Terence V. Powderly of the Knights of Labor as mayor of Scranton. After that, he became national leader of the KoL, a predominatelyPerhaps a bare majority, although the situation may have been different in Scranton.[محل شك] Catholic organization that had a peak membership of 700,000 circa 1880.[9] While the Catholic Church had prohibited membership in secret organizations since the mid-18th century, by the late 1880s with the influence of Archbishop James Gibbons of Baltimore, Maryland, it supported the Knights of Labor as representing workingmen and union organizing.

القرن العشرون

The landmark Coal strike of 1902 was called by anthracite miners across the region and led by the United Mine Workers under John Mitchell. The strike was settled by a compromise brokered by President Theodore Roosevelt. A statue of John Mitchell was installed in his honor on the grounds of the Lackawanna County Courthouse in Scranton, "the site of the Coal Strike of 1902 negotiations in which President Roosevelt participated. Because of the significance of these negotiations, the statue and the Courthouse were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1997. John Mitchell is buried in Cathedral Cemetery in Scranton."[10]

At the 1900 United States census, the population of Scranton was about 102,026, making it the third-largest city in Pennsylvania and 38th-largest U.S. city at the time.[11] At the turn of the 20th century, wealthy businessmen and industrialists built impressive Victorian mansions in the Hill and Green Ridge sections of the city. The industrial workers, who tended to be later immigrants from Ireland and southern and eastern Europe, were predominately Catholic. With a flood of immigrants in the market, they suffered poor working conditions and wages.

In 1902, the dwindling local iron ore supply, labor issues, and an aging plant cost the city the industry on which it was founded. The Lackawanna Steel Company and many of its workers were moved to Lackawanna, New York, developed on Lake Erie just south of Buffalo. With a port on the lake, the company could receive iron ore shipped from the Mesabi Range in Minnesota, which was being newly mined.

Scranton forged ahead as the capital of the anthracite coal industry. Attracting the thousands of workers needed to mine coal, the city developed new neighborhoods dominated by Italian and Eastern European immigrants, who brought their foods, cultures and religions. Many of the immigrants joined the Democratic Party. Their national churches and neighborhoods were part of the history of the city. Several Catholic and Orthodox churches were founded and built during this period. A substantial Jewish community was also established, with most members coming from the Russian Empire and eastern Europe. Working conditions for miners were improved by the efforts of labor leaders such as John Mitchell, who led the United Mine Workers.

The sub-surface mining weakened whole neighborhoods, however, damaging homes, schools, and businesses when the land collapsed. In 1913 the state passed the Davis Act to establish the Bureau of Surface Support in Scranton. Because of the difficulty in dealing with the coal companies, citizens organized the Scranton Surface Protection Association, chartered by the Court of Common Pleas on November 24, 1913 "to protect the lives and property of the citizens of the City of Scranton and the streets of said city from injury, loss and damage caused by mining and mine caves."[12]

In 1915 and 1917, the city and Commonwealth sought injunctions to prevent coal companies from undermining city streets but lost their cases. North Main Avenue and Boulevard Avenue, "both entitled to surface support, caved in as a result" of court decisions that went against civil authorities and allowed the coal companies to continue their operations.[12]

"The case of Penman v. Jones came out differently. The Lackawanna Iron & Coal Co. had leased coal lands to the Lackawanna Iron & Steel Co., an allied interest, which passed the leases on to the Scranton Coal Co. Areas of central Scranton, the Hill Section, South Side, Pine Brook, Green Ridge and Hyde Park were affected by their mining activities. Mr. Penman was the private property owner in the case. The coal operators were defeated in this case."[12]

The public transportation system began to expand beyond the trolley lines pioneered by predecessors of the Scranton Railways system. The Lackawanna and Wyoming Valley Railroad, commonly referred to as the Laurel Line, was built as an interurban passenger and freight carrier to Wilkes-Barre. Its Scranton station, offices, powerhouse and maintenance facility were built on the former grounds of the Lackawanna Steel Company, and operations started in 1903. Beginning in 1907, Scrantonians could also ride trolley cars to the northern suburbs of Clarks Summit and Dalton. They could travel to Lake Winola and Montrose using the Northern Electric Railroad. After the 1920s, no new trolley lines were built, but bus operations were started and expanded to meet service needs. In 1934, Scranton Railways was re-incorporated as the Scranton Transit Company, reflecting that shift in transportation modes.[13]

Starting in the early 1920s, the Scranton Button Company (founded in 1885 and a major maker of shellac buttons) became one of the primary makers of phonograph records. They pressed records for Emerson (whom they bought in 1924), as well as Regal, Cameo, Romeo, Banner, Domino, Conqueror. In July 1929, the company merged with Regal, Cameo, Banner, and the U.S. branch of Pathé (makers of Pathé and Perfect) to become the American Record Corporation. By 1938, the Scranton company was also pressing records for Brunswick, Melotone, and Vocalion. In 1946, the company was acquired by Capitol Records, which continued to produce phonograph records through the end of the vinyl era.

By the mid-1930s, the city population had swelled beyond 140,000[11] due to growth in the mining and silk textile industries. World War II created a great demand for energy, which led to the highest production from mining in the area since World War I.

After World War II, coal lost favor to oil and natural gas as a heating fuel, largely because the latter types were more convenient to use. While some U.S. cities prospered in the post-war boom, the fortunes and population of Scranton (and the rest of Lackawanna and Luzerne counties) began to diminish. Coal production and rail traffic declined rapidly throughout the 1950s, causing a loss of jobs.

In 1954, Worthington Scranton and his wife, Marion Margery Scranton, contributed one million dollars to establish the Scranton Foundation (now the Scranton Area Community Foundation), which was launched to support charitable and educational organizations in the city of Scranton.[14]

The Knox Mine Disaster of January 1959 virtually ended the mining industry in Northeastern Pennsylvania. The waters of the Susquehanna River flooded the mines.[15][16] The DL&W Railroad, nearly bankrupted by the drop in coal traffic and the effects of Hurricane Diane, merged in 1960 with the Erie Railroad. Demand for public transportation also declined as new highways were built by federal subsidies and people purchased automobiles. In 1952, the Laurel Line ceased passenger service. The Scranton Transit Company, whose trolleys had given the city its nickname, transferred all operations to buses as the 1954 holiday season approached; by the end of 1971, it ceased all operations. The city was left without any public transportation system for almost a year until the Lackawanna County government formed COLTS, which began operations in late 1972 with 1950s-era GM busses from New Jersey.

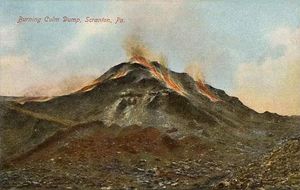

Scranton had been the hub of its operations until the Erie Lackawanna merger, after which it no longer served in this capacity. This was another severe blow to the local labor market. The NYO&W Railroad, which depended heavily on its Scranton branch for freight traffic, was abandoned in 1957. Mine subsidence was a spreading problem in the city as pillar supports in abandoned mines began to fail; cave-ins sometimes consumed entire blocks of homes. The area was left scarred by abandoned coal mining structures, strip mines, and massive culm dumps, some of which caught fire and burned for many years until they were extinguished through government efforts. In 1970, the Secretary of Mines for Pennsylvania suggested that so many underground voids had been left by mining underneath Scranton that it would be "more economical" to abandon the city than make them safe.[17] In 1973, the last mine operations in Lackawanna County (which were in what is now McDade Park, and another on the Scranton/Dickson City line) were closed. During the 1960s and 1970s, the silk and other textile industries shrank as jobs were moved to the South or overseas.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 1962, businessman Alex Grass opened his first "Thrif D Discount Center" drugstore on Lackawanna Avenue in downtown Scranton.[18][19] The 17-في-75-قدم (5 في 23 m) store, an immediate success, was the progenitor of the Rite Aid national drugstore chain.[18]

During the 1970s and 1980s, many downtown storefronts and theaters became vacant. Suburban development followed the highways and suburban shopping malls became the dominant venues for shopping and entertainment.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Since the mid-1980s, the city has emphasized revitalization. Local government and much of the community at large have adopted a renewed interest in the city's buildings and history. Some historic properties have been renovated and marketed as tourist attractions. The Steamtown National Historic Site captures the area's once-prominent position in the railroad industry. The former DL&W train station was restored as the Radisson Lackawanna Station Hotel. The Electric City Trolley Museum was created next to the DL&W yards that the Steamtown NHS occupies.

Since the mid-1980s the Scranton Cultural Center has operated the architecturally significant Masonic Temple and Scottish Rite Cathedral, designed by Raymond Hood, as the region's performing arts center. The Houdini Museum was opened in Scranton in 1990 by nationally known magician Dorothy Dietrich.

القرن 21

According to The Guardian, the city was close to bankruptcy in July 2012, with the wages of all municipal officials, including the mayor and fire chief, being cut to $7.25/hour.[21] Financial consultant Gary Lewis, who lived in Scranton, was quoted as estimating that "on 5 July the city had just $5,000 cash in hand."[21]

Since the revitalization began, many coffee shops, restaurants, and bars have opened in the downtown, creating a vibrant nightlife. The low cost of living, pedestrian-friendly downtown, and the construction of loft-style apartments in older, architecturally significant buildings have attracted young professionals and artists. Many are individuals who grew up in Scranton, moved to big cities after high school and college, and decided to return to the area to take advantage of its amenities. Many buildings around the city that were once empty are currently being restored. Many of the restored buildings will be used to entice new business into the city. Some of the newly renovated buildings are already being used.[22]

Attractions include the Montage Mountain ski resort, the Wilkes-Barre/Scranton Penguins, AHL affiliate of the Pittsburgh Penguins; the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders, AAA affiliate of the New York Yankees, PNC Field, and the Toyota Pavilion at Montage Mountain concert venue.

الجغرافيا

Scranton's total area of 25.4 ميل مربع (66 km2) includes 25.2 ميل مربع (65 km2) of land and 0.2 ميل مربع (0.52 km2) of water, according to the United States Census Bureau. Scranton is drained by the Lackawanna River.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Center City is about 750 feet (229 m) above sea level, although the hilly city's inhabited portions range about from 650 إلى 1،400 أقدام (200 إلى 430 m). The city is flanked by mountains to the east and west whose elevations range from 1،900 إلى 2،100 أقدام (580 إلى 640 m).[23][24]

المناخ

قالب:Scranton–Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania weatherbox

الديمغرافيا

| التعداد | Pop. | ملاحظة | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2٬730 | — | |

| 1860 | 9٬223 | 237٫8% | |

| 1870 | 35٬092 | 280٫5% | |

| 1880 | 45٬850 | 30٫7% | |

| 1890 | 75٬215 | 64�0% | |

| 1900 | 102٬026 | 35٫6% | |

| 1910 | 129٬867 | 27٫3% | |

| 1920 | 137٬783 | 6٫1% | |

| 1930 | 143٬433 | 4٫1% | |

| 1940 | 140٬404 | −2٫1% | |

| 1950 | 125٬536 | −10٫6% | |

| 1960 | 111٬443 | −11٫2% | |

| 1970 | 103٬564 | −7٫1% | |

| 1980 | 88٬117 | −14٫9% | |

| 1990 | 81٬805 | −7٫2% | |

| 2000 | 76٬415 | −6٫6% | |

| 2010 | 76٬089 | −0٫4% | |

| 2020 | 76٬328 | 0٫3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] 2018 Estimate[26] 2020[27][28] | |||

أشخاص بارزون

الفنون

- J. Grubb Alexander, silent film screenwriter

- Pete Barbutti, actor

- Walter Bobbie, theatre director and choreographer

- Alan Brown, filmmaker

- Sonny Burke, big band leader

- Mark Cohen, photographer

- Karl R. Coolidge, screenwriter

- Ann Crowley, singer and actress

- Emile de Antonio, documentary film director and producer

- Carrie De Mar, actress, singer, and vaudevillian

- Dorothy Dietrich, stage magician, escapologist, co-owner of Houdini Museum

- Margot Douaihy, writer and author

- Cy Endfield, screenwriter, film and theater director, author, magician, and inventor

- Ann Evers, film actress

- Wanda Hawley, silent film actress

- Allan Jones, singer and actor

- Jane Jacobs, writer and activist

- Gloria Jean, singer and actress

- Stephen Karam, playwright and screenwriter

- JP Karliak, actor, voice actor, and comedian

- Jean Kerr, author and playwright

- Michael Patrick King, television and film writer, director and producer, co-creator of 2 Broke Girls and The Comeback

- William Kotzwinkle, novelist and screenwriter

- Michael Kuchwara, theater critic, columnist, and journalist

- Gershon Legman, cultural critic and folklorist

- Bradford Louryk, theater artist and actor

- Charles Emmett Mack, actor

- Jeanne Madden, singer, star of musical theater and 1930s films

- Carl Marzani, political activist, volunteer soldier in Spanish Civil War, organizer for the Communist Party USA, U.S. intelligence official, documentary filmmaker, author, and publisher

- Judy McGrath, MTV Networks CEO

- Charles MacArthur, playwright and screenwriter

- The Menzingers, punk band

- W. S. Merwin, 17th U.S. Poet Laureate

- Jason Miller, actor, director, and Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright of That Championship Season

- Russ Morgan, big band-era bandleader

- Motionless in White, gothic metalcore band

- Bruce Mozert, photographer

- Jay Parini, writer and academic

- Jerry Penacoli, actor and director

- Byrne Piven, stage actor

- Cynthia Rothrock, martial artist and star of martial arts films

- Lizabeth Scott, actress and singer

- Katy Selverstone, actress, Lisa Robbins on The Drew Carey Show

- Melanie Smith, television actress

- Thomas L. Thomas, concert singer

- Tigers Jaw, indie rock, emo band

- Beverly Tyler, actress and singer

- Sally Victor, milliner

- Ned Washington, Academy Award-winning lyricist

- Lauren Weisberger, author, The Devil Wears Prada

- Michael Scott, Regional Manager, Scranton branch of Dunder Mifflin

الحكومة

- جو بايدن، رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 46 (2021–الحاضر)، نائب رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 47، وسناتور الولايات المتحدة عن دلاوير (1973–2009)

- John Blake, former Pennsylvania State Senator

- Marion Cowan Burrows, former Massachusetts state legislator

- Frank Carlucci, former U.S. Secretary of Defense and ambassador to Portugal

- Robert P. Casey, former governor of Pennsylvania

- Robert P. Casey Jr., U.S. senator

- Gaynor Cawley, former Pennsylvania State Representative

- John Cusick, retired lieutenant general and 42nd Quartermaster General of the United States Army

- David J. Davis, former Pennsylvania lieutenant governor

- Mike Dunleavy, governor of Alaska

- Hugh E. Rodham, father of Hillary Clinton[29]

- Hermann Eilts, former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Bangladesh

- John R. Farr, U.S. Congressman

- Kathleen Kane, former Pennsylvania attorney general and felon[30]

- Terence V. Powderly, former head of Knights of Labor

- Robert Reich, professor and political commentator, former U.S. Secretary of Labor

- Mary Scranton, former First Lady of Pennsylvania[31]

- William Scranton, former governor of Pennsylvania and U.S. ambassador to the United Nations

- William Scranton III, former Pennsylvania lieutenant governor

- Joel Wachs, Los Angeles city council member

- John Anthony Walker, former U.S. Navy chief warrant officer convicted of spying for the Soviet Union[32]

- Laurence Hawley Watres. U.S. Congressman[33]

- Louis A. Watres, Pennsylvania lieutenant governor[33]

Sports

- Hank Bullough, NFL player and coach

- P. J. Carlesimo, college, Olympic, and professional basketball coach and television broadcaster

- Jimmy Caras, professional pool player

- Nick Chickillo, former NFL player

- Nestor Chylak, Baseball Hall of Famer and former American League umpire

- Joe Collins, Major League Baseball player, six-time World Series champion

- Patty Costello, professional bowler, International Bowling Congress Hall of Fame, and Pro Bowlers Tour Hall of Fame member

- Jim Crowley, football player and coach, one-fourth of University of Notre Dame's legendary "Four Horsemen" backfield

- Paul Foytack, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Charlie Gelbert, Major League Baseball player

- Joe Grzenda, Major League Baseball player

- Cosmo Iacavazzi, college and AFL player

- Edgar Jones, college and professional football player

- Jerome Kapp, NFL wide receiver

- Gary Lavelle, Major League Baseball player

- Bill Lazor, NFL offensive coordinator

- Dave Lettieri, Olympic cyclist

- Ralph Lomma, popularized miniature golf

- Mike Lynn, general manager and executive Minnesota Vikings

- Joe McCarthy, Major League Baseball player

- Jake McCarthy, Major League Baseball player

- Matt McGloin, former NFL quarterback

- Gerry McNamara, former basketball player and current head coach of the Siena Saints men's basketball team.

- Mike McNally, former Major League Baseball player, member of New York Yankees first World Series championship team

- Mike Munchak, former head coach of NFL's Tennessee Titans, college and NFL player, member of Pro Football Hall of Fame

- Joe O'Malley, football player

- Jim O'Neill, Major League Baseball player

- Steve O'Neill, former Major League Baseball player and manager

- Jackie Paterson, Scottish boxer

- Jimmy Piersall, Major League Baseball player and Scranton Miners Minor League Baseball player

- Jim Rempe, pocket billiards champion and member of the Billiard Congress of America Hall of Fame

- Adam Rippon, figure skater

- Tim Ruddy, college and National Football League player

- Dutch Savage, professional wrestler

- Greg Sherman, general manager of NHL's Colorado Avalanche

- Chick Shorten, Major League Baseball player

- Marc Spindler, college and NFL player

- Brian Stann, mixed martial artist, UFC analyst for Fox Sports, former WEC Light Heavyweight champion

- Jim Williams (powerlifter), world record holding powerlifter

غيرهم

- Joseph Bambera, Bishop of Scranton

- Mamie Cadden, Irish midwife and murderer

- Lisa Caputo, Citigroup group

- Howard Gardner, developmental psychologist and professor

- Frank Gibney, journalist and scholar

- Hugh Glass, American frontiersman

- Alex Grass, founder of Rite Aid

- Isaiah Fawkes Everhart, American physician, naturalist, and founder of Everhart Museum

- Lansing C. Holden, architect

- Charles David Keeling, environmental scientist

- Jeffrey Bruce Klein, investigative journalist, co-founded Mother Jones magazine

- Francis T. McAndrew, Psychologist, Professor, Author

- Gino J. Merli, Medal of Honor recipient during World War II

- John Mitchell, labor organizer, founding member and president, United Mine Workers of America

- Robert C. Morlino, Bishop of Madison, Wisconsin

- John Joseph O'Connor, former bishop of Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York and Bishop of Scranton

- Karen Ann Quinlan, key figure in right to die controversy

- William Henry Richmond, coal mine operator

- Martin F. Scanlon, U.S. Air Force general

- B. F. Skinner, behaviorist and author

- Mabel Cox Surdam, photographer

- Charles Sumner "Sum" Woolworth, retailer, philanthropist, co-founder of Woolworth

- Mel Ziegler, co-founder, The Republic of Tea and Banana Republic

في الثقافة الشعبية

- The Harry Chapin song "30,000 Pounds of Bananas" is about an actual fatal 1965 accident in Scranton, where a driver hauling bananas lost control of his truck as it barreled down Moosic Street.[34]

- Blue Valentine was partially filmed in Scranton.

- The film adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and Tony Award winning play That Championship Season is set in and was filmed in Scranton.

- The city is home to the Pennsylvania Paper and Supply Company, which was the inspiration for a branch of the fictional paper company Dunder Mifflin on NBC's series The Office. The Scranton branch is the setting for the majority of the show's episodes.[35]

- The city was the setting of the home of Roy Munson (portrayed by Woody Harrelson) in the 1996 American sports comedy Kingpin. The scenes were shot in Pittsburgh as a stand in for Scranton.

- The city is imagined as a member of the class of interstellar Okies in James Blish's 1962 novel A Life for the Stars, in which 2273 AD Scranton, equipped with a space drive, flies away and leaves an impoverished Earth behind.

- In 2017, Scranton got national recognition from late night television host John Oliver when he made jokes about how infatuated Scranton community members were with the little train that runs during the weather reports on Scranton's ABC-affiliated TV station WNEP-TV. The train had been featured in multiple of their "Talkback 16" segments. After a follow-up segment, Oliver donated a train set to WNEP. It was too big for their backyard, so they donated it to the Electric City Trolley Museum.[36]

- Musician John Legend was the head of the music department and choir director of Scranton's Bethel AME Church from 1995 to 2004.[37]

- Lyricist Richard Bernhard Smith wrote the song, "Winter Wonderland", while being treated at the West Mountain Sanitarium in Scranton for tuberculosis.

- American singer, actress and television personality Cher lived in Scranton as a baby and spent time at a Catholic orphanage in the city run by the Sisters of Mercy. Cher wrote about the experience in the song, "Sisters of Mercy".[38][39]

- American author and film & television producer Dick Wolf was married to Susan Scranton, daughter of former Governor William Scranton, from 1970 to 1983.

- American radio talk show host, television broadcaster, and politician Dan Patrick began his broadcast career at WNEP-TV in Scranton.

- American conservative commentator, journalist, author, and television host Bill O'Reilly's early television career began at WNEP-TV in Scranton, where he served as a news and weather reporter, and as a news anchor later on.

المدن الشقيقة

Scranton has the following official sister cities:

Ballina, County Mayo, Connacht, Ireland

Ballina, County Mayo, Connacht, Ireland Guardia Lombardi, Campania, Italy

Guardia Lombardi, Campania, Italy Balakovo, Saratov Oblast, Russia

Balakovo, Saratov Oblast, Russia Trnava, Slovakia

Trnava, Slovakia Perugia, Umbria, Italy

Perugia, Umbria, Italy San Marino, San Marino

San Marino, San Marino كارونيا، صقلية، إيطاليا

كارونيا، صقلية، إيطاليا

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSCensusEst2019CenPopScriptOnlyDirtyFixDoNotUse - ^ "Scranton, Wilkes, Barre Metro Area". Usa.com. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-39E

- ^ "Pennsylvania Historical Marker Search". www.phmc.state.pa.us.

- ^ Kashuba, Cheryl A (22 August 2010). "Scranton gained fame as the Electric City, thanks to the region's innovative spirit". Scranton Times-Tribune. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Azzarelli, Margo L.; Marnie Azzarelli (2016). Labor Unrest in Scranton. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781625856814. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ Vincent J. Falzone, "Terence V. Powderly: Politician and Progressive Mayor of Scranton, 1878-1884," Pennsylvania History 41.3 (1974): 289-309.

- ^ Sarah Scinto (October 30, 2013). "Labor leader's grave restored". Scranton Times-Tribune. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Scranton(city) QuickFacts". Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ^ أ ب ت Cheryl A. Kashuba, "Scranton takes on mining, cave-ins" Archived يونيو 17, 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Times-Tribune, October 10, 2010, accessed May 23, 2016

- ^ The Scranton Republican, July 5, 1934, "Railway Firm's New Financial Setup Revealed", p. 1

- ^ "W. Scranton Dies in Florida Archived 2021-07-13 at the Wayback Machine." Hazleton, Pennsylvania: The Plain Speaker, February 14, 1955, p. 20.

- ^ "The Citizens Voice – Knox mine disaster remains in our memory because it is a story of right and wrong". Zwire.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ "cover". Msha.gov. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1998). Facts & Trivia. Bristol: Siena. p. 74. ISBN 0-75252-822-X.

- ^ أ ب Klaus, Mary (August 28, 2009). "Beacon of generosity". Harrisburg Patriot-News. Retrieved August 31, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Falchek, David (August 29, 2009). "Scranton native and Rite Aid founder Alex Grass dies after 10-year battle with lung cancer". Scranton Times. Retrieved August 31, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Scranton, A City That's Seen Many Come and Go". Grapple. Keystone Crossroads. October 4, 2016. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ أ ب Harris, Paul (July 14, 2012). "Scranton, Pennsylvania: Where even the mayor is on minimum wage". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ Rich, Megan (September 27, 2012). ""From Coal To Cool": The Creative Class, Social Capital, And The Revitalization Of Scranton". Journal of Urban Affairs. 35 (3): 365–384. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00639.x. S2CID 143899777.

- ^ "West Mountain in Lackawanna County PA (Scranton Area)". Mountain Zone.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "Moosic Mountains High Point". Peak Bagger. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.[dead link]

- ^ "Census 2020".

- ^ "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Clinton's girlhood home in Pa. (sort of) Lake Winola may have primary role. – philly-archives". Articles.philly.com. November 2, 2011. Archived from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Hurdle, Jon; Pérez-Peña, Richard (October 24, 2016). "Kathleen Kane, Former Pennsylvania Attorney General, Is Sentenced to Prison". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ O'Connell, Jon (December 28, 2015). "Former Pennsylvania first lady Mary L. Scranton, 97, dies". The Citizens' Voice. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Murray, Thomas H. (September 4, 2014). Espionage and the United States During the 20th Century. Dorrance Publishing. p. 153. ISBN 9781434930521. OCLC 890757936.

- ^ أ ب "The Life and Works of Col. L. A. Watres" (PDF). Lackawanna History Society Bulletin. 16 (2). April 1983. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Buynovsky, Sarah (March 18, 2015). "The 'Banana Truck' Crash: 50 Years Later". WNEP. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ Craft, Kevin (May 16, 2013). "The Thing That Made The Office Great Is the Same Thing That Killed It". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Whitehead, Anja (September 25, 2017). "John Oliver Reacts to Thousands Flocking to See the New Backyard Train". WNEP. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ Aversa, Ralphie (December 7, 2016). "John Legend on His Gospel Roots, PA Ties and New Album". RalphieAversa.com.

- ^ Library, Reference Department, Albright Memorial (2005-08-24). "Scranton & Wilkes-Barre in Entertainment: "Sisters of Mercy" by Cher (2000)". Scranton & Wilkes-Barre in Entertainment. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cher Song Upsets Catholics, Calling Nuns 'Daughters Of Hell'". MTV (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-12-03.

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with dead external links from February 2024

- Articles with dead external links from September 2010

- Articles with dead external links from June 2022

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible nickname list

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible motto list

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- مقالات ذات عبارات محل شك

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2010

- Pages with empty portal template

- سكرانتون، پنسلڤانيا

- مدن مقاطعة لاكاوانا، پنسلڤانيا

- مدن پنسلڤانيا

- County seats in Pennsylvania

- Lackawanna Heritage Valley

- Municipalities of the Anthracite Coal Region of Pennsylvania

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في 1778

- تأسيسات 1778 في پنسلڤانيا

- صفحات مع الخرائط