وب دلالي

الوب الدلالي Semantic Web عبارة عن امتداد لـ شبكة الوب العالمية من خلال المعايير التي وضعتها جمعية شبكة الوب العالمية (W3C).[1] الهدف من الويب الدلالي هو جعل بيانات الإنترنت قابلة للقراءة آلياً. لتمكين ترميز الدلالات مع البيانات، يتم استخدام إطار وصف المصدر (RDF)[2] و لغة أنطولوجيا الوب (OWL)[3]. تُستخدم هذه التقنيات لتمثيل البيانات الوصفية رسمياً. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن تصف الأنطولوجيا المفاهيم والعلاقات بين الكيانات وفئات الأشياء. توفر هذه الدلالات المضمنة مزايا مهمة مثل التفكير المنطقي عبر البيانات والعمل مع مصادر البيانات غير المتجانسة.[4]

تعزز هذه المعايير تنسيقات البيانات المشتركة وپروتوكولات التبادل على الويب، وبشكل أساسي RDF. وفقًا لـ W3C، "يوفر الوب الدلالي إطاراً مشتركاً يسمح بمشاركة البيانات وإعادة استخدامها عبر حدود التطبيقات والمؤسسات والمجتمع."[5] لذلك، يُنظر إلى الويب الدلالي على أنه عامل تكامل عبر تطبيقات وأنظمة مختلفة للمحتوى والمعلومات.

تمت صياغة المصطلح بواسطة تيم بيرنرز-لي لشبكة من البيانات (أو شبكة البيانات)[6]التي يمكن معالجتها بواسطة الآلات[7]—وهذا يعني أن الكثير من المعاني يمكن قراءتها آلياً. بينما شكك نقادها في جدواها، حيث يجادل المؤيدون بأن التطبيقات في علوم المكتبات والمعلومات والصناعة وعلم الأحياء والعلوم الإنسانية قد أثبتت بالفعل صحة المفهوم الأصلي.[8]

أعرب بيرنرز-لي في الأصل عن رؤيته للويب الدلالي في عام 1999 على النحو التالي:

لدي حلم للويب [حيث تصبح أجهزة الحاسب] قادرة على تحليل جميع البيانات الموجودة على الويب – المحتوى والروابط والمعاملات بين الأشخاص وأجهزة الحاسب. "الوب الدلالي"، الذي يجعل هذا ممكناً، لم يظهر بعد، ولكن عندما يحدث ذلك، فإن الآليات اليومية للتجارة والبيروقراطية وحياتنا اليومية ستتم معالجتها بواسطة آلات تتحدث إلى الآلات. أخيراً سيتجسد "الوكلاء الأذكياء" الأشخاص الذين روجوا لها على مر العصور.[9]

وصفت مقالة ساينتفك أميركان الصادرة عام 2001 بقلم بيرنرز-لي و هندلر و لاسيلا تطوراً متوقعاً للويب الحالي إلى شبكة ويب دلالية.[10] في عام 2006، صرح بيرنرز-لي وزملاؤه أن: "هذه الفكرة البسيطة ... لا تزال غير محققة إلى حد كبير".[11] في عام 2013، احتوى أكثر من أربعة ملايين نطاق ويب على ترميز الويب الدلالي.[12]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

مثال

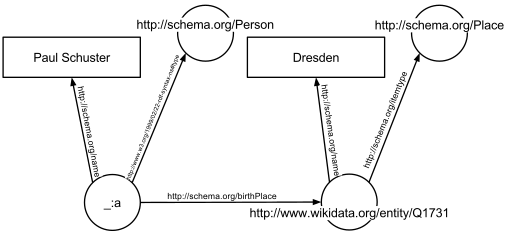

في المثال التالي، سيتم إضافة تعليق توضيحي للنص "ولد پول شوستر في دريسدن" على أحد مواقع الويب، بحيث يربط الشخص بمحل ميلاده. يوضح الجزء HTML التالي كيفية وصف رسم بياني صغير، في RDFa - بناء الجملة باستخدام schema.org مفردات ومعرف بيانات ويكي:

<div vocab="http://schema.org/" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Paul Schuster</span> was born in

<span property="birthPlace" typeof="Place" href="http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731">

<span property="name">Dresden</span>.

</span>

</div>

يعرّف المثال الثلاثيات الخمس التالية (موضحة في بناء الجملة السلحفاة)تمثل كل ثلاثية حد واحد في الرسم البياني الناتج: العنصر الأول من الثلاثي (الموضوع) هو اسم العقدة حيث تبدأ الحافة، والعنصر الثاني (المفعول به) هو نوع حد، والعنصر الأخير والثالث (الشيء) إما اسم العقدة التي تنتهي عندها الحد أو قيمة حرفية (مثل نص، أو رقم، وما إلى ذلك).

_:a <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://schema.org/Person> . _:a <http://schema.org/name> "Paul Schuster" . _:a <http://schema.org/birthPlace> <http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> . <http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <http://schema.org/itemtype> <http://schema.org/Place> . <http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <http://schema.org/name> "Dresden" .

النتائج الثلاثية في الرسم البياني الموضح في الشكل المعطى.

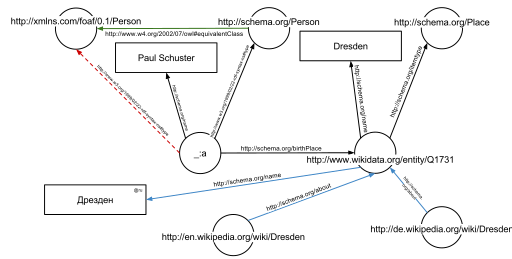

تتمثل إحدى مزايا استخدام معرف المصدر الموحد (URIs) في أنه يمكن إلغاء الإشارة إليها باستخدام پروتوكول HTTP. وفقاً لما يسمى بمبادئ البيانات المفتوحة المرتبطة، يجب أن ينتج عن هذا URI الذي تم إلغاء مرجعيته مستنداً يقدم مزيدًا من البيانات حول URI المحدد. في هذا المثال، جميع URIs، للحواف والعقد (على سبيل المثال http://schema.org/Personhttp://schema.org/birthPlacehttp://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731

يُظهر الرسم البياني الثاني المثال السابق، ولكنه الآن مقوى بعدد قليل من الأشكال الثلاثية من المستندات الناتجة عن إلغاء الإسناد http://schema.org/Personhttp://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731

بالإضافة إلى الحواف الواردة في المستندات المعنية بشكل صريح، يمكن استنتاج الحواف تلقائياً:

_:a <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://schema.org/Person> .

من جزء RDFa الأصلي و

<http://schema.org/Person> <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#equivalentClass> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person> .

من المستند في http://schema.org/Person

خلفية

تم تشكيل مفهوم نموذج الشبكة الدلالية في أوائل الستينيات من قبل باحثين مثل العالم المعرفي ألان إم كولينز وعالم اللغويات إم. روس كويليان وعالمة النفس إليزابيث إف. لوفتوس كصيغة لتمثيل المعرفة المنظمة لغوياً. عند تطبيقه في سياق الإنترنت الحديث، فإنه يوسع شبكة ارتباط تشعبي قابلة للقراءة من قبل مستخدم صفحات الويب عن طريق إدراج البيانات الوصفية التي يمكن قراءتها آلياً حول الصفحات وكيفية ارتباطها ببعضها البعض. يتيح ذلك للوكلاء الآليين الوصول إلى الويب بشكل أكثر ذكاء وأداء المزيد من المهام نيابة عن المستخدمين. مصطلح "الويب الدلالي" ابتكره تيم بيرنرز لي،[7]وهو مخترع شبكة الوب العالمية ومدير اتحاد شبكة وب العالمية ("W3C")، الذي يشرف على تطوير معايير الوب الدلالية المقترحة. يعرّف الوب الدلالي بأنه "شبكة من البيانات يمكن معالجتها بشكل مباشر وغير مباشر بواسطة الآلات".

العديد من التقنيات التي اقترحها W3C موجودة بالفعل قبل وضعها تحت مظلة W3C. والتي تُستخدم في سياقات مختلفة، لا سيما تلك التي تتعامل مع المعلومات التي تشمل مجالاً محدوداً ومحدّداً، وحيث تكون مشاركة البيانات ضرورة مشتركة، مثل البحث العلمي أو تبادل البيانات بين الشركات. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، ظهرت تقنيات أخرى ذات أهداف مماثلة، مثل مايكروفورمات.

حدود HTML

يمكن أيضاً تقسيم العديد من الملفات الموجودة على جهاز حاسب نموذجي إلى وثائق يمكن قراءتها بواسطة المستخدم و بيانات يمكن قراءتها آلياً. يقرأ البشر مستندات مثل رسائل البريد والتقارير والكتيبات. يتم تقديم البيانات، مثل التقويمات ودفاتر العناوين وقوائم التشغيل وجداول البيانات باستخدام برنامج تطبيق يتيح عرضها والبحث عنها ودمجها.

حاليًا ، تعتمد شبكة الوب العالمية بشكل أساسي على المستندات المكتوبة بـ لغة ترميز النصوص التشعبية (HTML) ، وهي عبارة عن اصطلاح ترميز يُستخدم لترميز مجموعة نصية تتخللها مواضيع وسائط متعددة مثل الصور والنماذج التفاعلية . توفر علامات البيانات الوصفية طريقة يمكن لأجهزة الحاسب من خلالها تصنيف محتوى صفحات الوب. في الأمثلة أدناه، يتم تعيين قيم لأسماء الحقول "الكلمات الرئيسية" و "الوصف" و "المؤلف" مثل "الحوسبة" و "الأدوات الرخيصة المعروضة للبيع" و "جون دو".

<meta name="keywords" content="computing, computer studies, computer" />

<meta name="description" content="Cheap widgets for sale" />

<meta name="author" content="John Doe" />

بسبب وضع علامات البيانات الوصفية وتصنيفها، يمكن لأنظمة الحاسب الأخرى التي ترغب في الوصول إلى هذه البيانات ومشاركتها تحديد القيم ذات الصلة بسهولة.

باستخدام HTML وأداة لعرضها (ربما برنامج متصفح وب، وربما برنامج آخر وكيل المستخدم)، يمكن للمرء إنشاء وتقديم صفحة تسرد العناصر المعروضة للبيع. يمكن أن يقوم HTML لصفحة الكتالوگ هذه بعمل تأكيدات بسيطة على مستوى المستند مثل "عنوان هذا المستند هو 'Widget Superstore'"، ولكن لا توجد إمكانية داخل HTML نفسه لتأكيد ذلك، على سبيل المثال، رقم العنصر X586172 هو جهاز Acme Gizmo بسعر التجزئة 199 يورو، أو أنه منتج استهلاكي. بدلاً من ذلك، يمكن أن تقول HTML فقط أن امتداد النص "X586172" هو شيء يجب وضعه بالقرب من "Acme Gizmo" و "€ 199"، وما إلى ذلك. لا توجد طريقة لقول "هذا كتالوگ" أو حتى لإثبات ذلك "Acme Gizmo" هو نوع من العنوان أو أن "€ 199" سعر. لا توجد أيضاً طريقة للتعبير عن ارتباط هذه المعلومات ببعضها البعض في وصف عنصر منفصل، بعيدًا عن العناصر الأخرى التي ربما تكون مدرجة في الصفحة.

يشير HTML الدلالي إلى ممارسات HTML التقليدية المتمثلة في اتباع النية للترميز، بدلاً من تحديد تفاصيل التخطيط مباشرةً. على سبيل المثال، يشير استخدام <em> إلى "تأكيد" بدلاً من <i>، والتي تحدد الخط المائل. تُترك تفاصيل التنسيق للمتصفح، بالإضافة إلى صفحات الأنماط المتتالية. ولكن هذه الممارسة تقصر عن تحديد دلالات الأشياء مثل العناصر المعروضة للبيع أو الأسعار.

تعمل التنسيقات الدقيقة على توسيع بنية HTML لإنشاء ترميزاً دلالياً يمكن قراءته آلياً حول مواضيع بما في ذلك الأشخاص والمؤسسات والأحداث والمنتجات.[13]تشمل المبادرات المماثلة RDFa و بيانات دقيقة و Schema.org.

حلول الوب الدلالي

يأخذ الوب الدلالي الحل إلى أبعد من ذلك. يتضمن النشر بلغات مصممة خصيصاً للبيانات: إطار وصف المصدر (RDF) ولغة أنطولوجيا الوب (OWL) ولغة الترميز الموسعة (XML). يصف HTML المستندات والروابط بينها. على النقيض من ذلك، يمكن أن تصف RDF و OWL و XML أشياء عشوائية مثل الأشخاص أو الاجتماعات أو أجزاء الطائرة.

يتم الجمع بين هذه التقنيات لتوفير أوصاف تكمل أو تحل محل محتوى مستندات الويب. وبالتالي، قد يظهر المحتوى على أنه بيانات وصفية مخزنة في قواعد البيانات يمكن الوصول إليها عبر الوب،[14] أو كترميز داخل المستندات (على وجه الخصوص، في لغة HTML القابلة للتوسيع (XHTML) التي تتخللها XML، أو في الغالب بتنسيق XML البسيط، مع تخزين إشارات التخطيط أو العرض بشكل منفصل). تمكّن الأوصاف المقروءة آلياً مديري المحتوى من إضافة معنى إلى المحتوى، أي لوصف بنية المعرفة التي لدينا حول هذا المحتوى. بهذه الطريقة، يمكن للآلة معالجة المعرفة بنفسها، بدلاً من النص، باستخدام عمليات مشابهة لـ التفكير الاستنتاجي و الاستدلال، وبالتالي الحصول على نتائج ذات مغزى أكبر ومساعدة أجهزة الحاسب على القيام بجمع المعلومات والبحث الآلي. مثال على علامة يمكن استخدامها في صفحة وب غير دلالية:

<item>blog</item>

قد يبدو ترميز معلومات مماثلة في صفحة وب دلالية كما يلي:

<item rdf:about="http://example.org/semantic-web/">Semantic Web</item>

يدعو تيم بيرنرز-لي الشبكة الناتجة من البيانات المرتبطة بالرسم البياني العالمي العملاق، على عكس الشبكة العالمية المستندة إلى HTML. يفترض بيرنرز-لي أنه إذا كان الماضي هو مشاركة المستندات، فإن المستقبل هو مشاركة البيانات. تقدم إجابته على سؤال "كيف" ثلاث نقاط إرشادية. أولاً، يجب أن يشير عنوان URL إلى البيانات. ثانياً، يجب على أي شخص يقوم بالوصول إلى عنوان URL استعادة البيانات. ثالثاً، يجب أن تشير العلاقات في البيانات إلى عناوين URL إضافية بالبيانات.

وب 3.0

وصف تيم بيرنرز-لي الوب الدلالي بأنه أحد مكونات وب 3.0.[15]

يستمر الناس في التساؤل عن ماهية الوب 3.0. أعتقد أنه ربما عندما يكون لديك تراكب رسومات متجهية قابلة للتطوير – كل شيء متموج وقابل للطي ويبدو ضبابياً- على وب 2.0 والوصول إلى الوب الدلالي المدمج عبر مساحة ضخمة من البيانات، 'فسيكون لديك حق الوصول إلى مصدر بيانات لا يصدق …

— Tim Berners-Lee, 2006

يستخدم "الويب الدلالي" أحياناً كمرادف لـ "الوب 3.0" ،[16] على الرغم من اختلاف تعريف كل مصطلح. بدأ الوب 3.0 في الظهور كحركة بعيدة عن مركزية الخدمات مثل البحث والوسائط الاجتماعية وتطبيقات الدردشة التي تعتمد على مؤسسة واحدة لتؤدي عملها.[17]

راجع الصحفي جون هاريس في الگارديان مفهوم Web 3.0 بشكل إيجابي في أوائل ‑2019 وعلى وجه الخصوص، عمل بيرنرز‑لي في مشروع يسمى سوليد، استناداً إلى مخازن البيانات الشخصية أو "الپودات"، والتي يحتفظ الأفراد بالتحكم عليها.[18] وقد أسس بيرنرز‑لي شركة ناشئة، إنرَپت، لتعزيز الفكرة وجذب المطورين المتطوعين.[19][20]

التحديات

تتضمن بعض التحديات التي تواجه الوب الدلالي الاتساع والغموض وعدم اليقين وعدم الاتساق والخداع. سيتعين على أنظمة الاستدلال الآلي التعامل مع كل هذه القضايا من أجل تحقيق الوب الدلالي.

- الاتساع: تحتوي شبكة الوب العالمية على مليارات الصفحات. تحتوي SNOMED CT المصطلحات الطبية الأنطولوجيا وحدها على 370000 اسم فئة، ولم تتمكن التكنولوجيا الحالية بعد من إزالة جميع المصطلحات المكررة لغوياً. سيتعين على أي نظام استدلال آلي التعامل مع مدخلات ضخمة حقاً.

- الغموض: هذه مفاهيم غير دقيقة مثل "شاب" أو "طويل". ينشأ هذا من غموض استعلامات المستخدم، والمفاهيم التي يمثلها موفرو المحتوى، ومطابقة مصطلحات الاستعلام مع مصطلحات الموفر ومحاولة الجمع بين قواعد المعرفة المختلفة مع مفاهيم متداخلة ولكن مختلفة بشكل دقيق. المنطق الضبابي هو الأسلوب الأكثر شيوعًا للتعامل مع الغموض.

- عدم اليقين: هذه مفاهيم دقيقة بقيم غير مؤكدة. على سبيل المثال، قد يقدم المريض مجموعة من الأعراض التي تتوافق مع عدد من التشخيصات المميزة المختلفة لكل منها احتمال مختلف. يتم استخدام أساليب التفكير الاحتمالية بشكل عام لمعالجة عدم اليقين.

- عدم الاتساق: هذه تناقضات منطقية ستنشأ حتماً أثناء تطوير الأنطولوجيا الكبيرة، وعندما يتم الجمع بين الأنطولوجيا من مصادر منفصلة. يفشل الاستدلال الاستنتاجي بشكل كارثي عند مواجهة عدم الاتساق، لأن "أي شيء يتبع من التناقض". الاستدلال الغير مجدي و التفكير المتناقض هما أسلوبان يمكن استخدامهما للتعامل مع عدم الاتساق.

- الخداع: عندما يقوم منتج المعلومات عمداً بتضليل المستهلك للمعلومات. تستخدم تقنيات التشفير للتخفيف من هذا التهديد. من خلال توفير وسيلة لتحديد سلامة المعلومات، بما في ذلك تلك التي تتعلق بهوية الكيان الذي أنتج أو نشر المعلومات، ومع ذلك، لا يزال يتعين معالجة المصداقية قضايا في حالات الخداع المحتمل.

قائمة التحديات هذه توضيحية وليست شاملة، وهي تركز على التحديات التي تواجه "المنطق الموحد" وطبقات "الإثبات" للويب الدلالي. تجمع مجموعة حاضنة اتحاد شبكة الوب العالمية (W3C) لاستدلال عدم اليقين لشبكة الوب العالمية (URW3-XG) هذه المشكلات معاً تحت عنوان واحد "عدم اليقين".[21]ستتطلب العديد من التقنيات المذكورة هنا امتدادات للغة أنطولوجيا الويب (OWL) على سبيل المثال للتعليق على الاحتمالات الشرطية. فهذا مجال بحث نشط.[22]

المعايير

توحيد معايير الويب الدلالي في سياق الويب 3.0 تحت رعاية W3C.[23]

المكونات

غالباً ما يستخدم مصطلح "الويب الدلالي" بشكل أكثر تحديداً للإشارة إلى التنسيقات والتقنيات التي تمكّنه.[5]يتم تمكين جمع وتنظيم واستعادة البيانات المرتبطة بواسطة التقنيات التي توفر وصف رسمي للمفاهيم والمصطلحات والعلاقات داخل مجال المعرفة. تم تحديد هذه التقنيات كمعايير W3C وتشمل:

- إطار وصف الموارد (RDF)، طريقة عامة لوصف المعلومات

- مخطط RDF (RDFS)

- نظام تنظيم المعرفة البسيط (SKOS)

- SPARQL، لغة استعلام RDF

- تأشير3 (N3)، تم تصميمه مع مراعاة سهولة القراءة من قبل المستخدم

- N-ثلاثية، تنسيق لتخزين ونقل البيانات

- تيرتل (لغة RDF الوجيزة الثلاثية)

- لغة أنطولوجيا الوب (OWL)، وهي عائلة من لغات تمثيل المعرفة

- تنسيق تبادل القاعدة (RIF)، إطار عمل أشكال معينة من لغات قواعد الوب التي تدعم تبادل القواعد على الوب

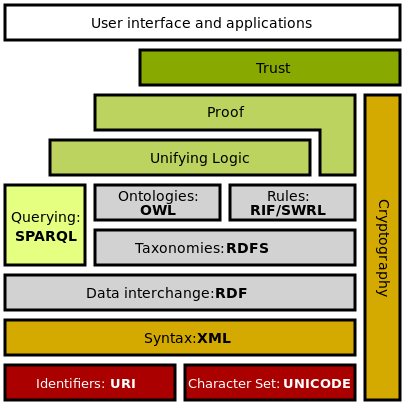

يوضح مكدس الوب الدلالي بنية الوب الدلالي. يمكن تلخيص وظائف وعلاقات المكونات على النحو التالي:[24]

- يوفر XML بناء جملة عنصري أساسي لهيكل المحتوى داخل المستندات، ومع ذلك لا يربط أي دلالات بمعنى المحتوى المتضمن داخلها. XML ليست في الوقت الحالي مكوناً ضرورياً لتقنيات الوب الدلالي في معظم الحالات، حيث توجد صيغ بديلة، مثل تيرتل. تيرتل هو معيار واقعي، لكنه لم يخضع لعملية معايرة رسمية.

- مخطط XML هي لغة لتوفير وتقييد بنية ومحتوى العناصر المضمنة في مستندات XML.

- RDF هي لغة بسيطة للتعبير عن نماذج البيانات، والتي تشير إلى مواضيع ("موارد ويب" وعلاقاتهم. يمكن تمثيل النموذج المستند إلى RDF في مجموعة متنوعة من الصيغ، على سبيل المثال، RDF / XML و N3 و تيرتل و RDFa. RDF هو معيار أساسي للوب الدلالي.[25][26]

- يمتد مخطط RDF إلى RDF وهو مفردات لوصف خصائص وفئات الموارد المستندة إلى RDF، مع دلالات للتسلسلات الهرمية المعممة لهذه الخصائص والفئات.

- يضيف OWL المزيد من المفردات لوصف الخصائص والفئات: من بين أمور أخرى، العلاقات بين الفئات (مثل عدم الترابط)، والعلاقة الأساسية (على سبيل المثال، "واحد تماماً")، والمساواة، وكتابة الخصائص الأكثر ثراءً، وخصائص الخصائص (مثل التناظر)، والفئات المعدودة.

- SPARQL هي لغة پروتوكول واستعلام لمصادر بيانات الوب الدلالية.

- RIF هو تنسيق W3C لتبادل القواعد. فهي لغة XML للتعبير عن قواعد الوب التي يمكن لأجهزة الحاسب تنفيذها. يوفر RIF إصدارات متعددة تسمى أنماط اللغة. يتضمن نمط اللغة المنطق الأساسية RIF (RIF-BLD) نمط لغة قواعد إنتاج (RIF PRD).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الوضع الحالي للمعايرة

المعايير الراسخة:

- RDF

- RDFS

- تنسيق تبادل القاعدة (RIF)

- SPARQL

- يونيكود

- معرف الموارد الموحد

- لغة أنطولوجيا الوب (OWL)

- XML

لم تتحقق بالكامل بعد:

- توحيد طبقات المنطق والإثبات

- لغة قاعدة الوب الدلالية (SWRL)

Applications

The intent is to enhance the usability and usefulness of the Web and its interconnected resources by creating semantic web services, such as:

- Servers that expose existing data systems using the RDF and SPARQL standards. Many converters to RDF exist from different applications.[27] Relational databases are an important source. The semantic web server attaches to the existing system without affecting its operation.

- Documents "marked up" with semantic information (an extension of the HTML

<meta> - Common metadata vocabularies (ontologies) and maps between vocabularies that allow document creators to know how to mark up their documents so that agents can use the information in the supplied metadata (so that Author in the sense of 'the Author of the page' won't be confused with Author in the sense of a book that is the subject of a book review).

- Automated agents to perform tasks for users of the semantic web using this data.

- Web-based services (often with agents of their own) to supply information specifically to agents, for example, a Trust service that an agent could ask if some online store has a history of poor service or spamming.

Such services could be useful to public search engines, or could be used for knowledge management within an organization. Business applications include:

- Facilitating the integration of information from mixed sources

- Dissolving ambiguities in corporate terminology

- Improving information retrieval thereby reducing information overload and increasing the refinement and precision of the data retrieved[29][30][31][32]

- Identifying relevant information with respect to a given domain[33]

- Providing decision making support

In a corporation, there is a closed group of users and the management is able to enforce company guidelines like the adoption of specific ontologies and use of semantic annotation. Compared to the public Semantic Web there are lesser requirements on scalability and the information circulating within a company can be more trusted in general; privacy is less of an issue outside of handling of customer data.

Skeptical reactions

Practical feasibility

Critics question the basic feasibility of a complete or even partial fulfillment of the Semantic Web, pointing out both difficulties in setting it up and a lack of general-purpose usefulness that prevents the required effort from being invested. In a 2003 paper, Marshall and Shipman point out the cognitive overhead inherent in formalizing knowledge, compared to the authoring of traditional web hypertext:[34]

While learning the basics of HTML is relatively straightforward, learning a knowledge representation language or tool requires the author to learn about the representation's methods of abstraction and their effect on reasoning. For example, understanding the class-instance relationship, or the superclass-subclass relationship, is more than understanding that one concept is a “type of” another concept. […] These abstractions are taught to computer scientists generally and knowledge engineers specifically but do not match the similar natural language meaning of being a "type of" something. Effective use of such a formal representation requires the author to become a skilled knowledge engineer in addition to any other skills required by the domain. […] Once one has learned a formal representation language, it is still often much more effort to express ideas in that representation than in a less formal representation […]. Indeed, this is a form of programming based on the declaration of semantic data and requires an understanding of how reasoning algorithms will interpret the authored structures.

According to Marshall and Shipman, the tacit and changing nature of much knowledge adds to the knowledge engineering problem, and limits the Semantic Web's applicability to specific domains. A further issue that they point out are domain- or organisation-specific ways to express knowledge, which must be solved through community agreement rather than only technical means.[34] As it turns out, specialized communities and organizations for intra-company projects have tended to adopt semantic web technologies greater than peripheral and less-specialized communities.[35] The practical constraints toward adoption have appeared less challenging where domain and scope is more limited than that of the general public and the World-Wide Web.[35]

Finally, Marshall and Shipman see pragmatic problems in the idea of (Knowledge Navigator-style) intelligent agents working in the largely manually curated Semantic Web:[34]

In situations in which user needs are known and distributed information resources are well described, this approach can be highly effective; in situations that are not foreseen and that bring together an unanticipated array of information resources, the Google approach is more robust. Furthermore, the Semantic Web relies on inference chains that are more brittle; a missing element of the chain results in a failure to perform the desired action, while the human can supply missing pieces in a more Google-like approach. […] cost-benefit tradeoffs can work in favor of specially-created Semantic Web metadata directed at weaving together sensible well-structured domain-specific information resources; close attention to user/customer needs will drive these federations if they are to be successful.

Cory Doctorow's critique ("metacrap") is from the perspective of human behavior and personal preferences. For example, people may include spurious metadata into Web pages in an attempt to mislead Semantic Web engines that naively assume the metadata's veracity. This phenomenon was well known with metatags that fooled the Altavista ranking algorithm into elevating the ranking of certain Web pages: the Google indexing engine specifically looks for such attempts at manipulation. Peter Gärdenfors and Timo Honkela point out that logic-based semantic web technologies cover only a fraction of the relevant phenomena related to semantics.[36][37]

Censorship and privacy

Enthusiasm about the semantic web could be tempered by concerns regarding censorship and privacy. For instance, text-analyzing techniques can now be easily bypassed by using other words, metaphors for instance, or by using images in place of words. An advanced implementation of the semantic web would make it much easier for governments to control the viewing and creation of online information, as this information would be much easier for an automated content-blocking machine to understand. In addition, the issue has also been raised that, with the use of FOAF files and geolocation meta-data, there would be very little anonymity associated with the authorship of articles on things such as a personal blog. Some of these concerns were addressed in the "Policy Aware Web" project[38] and is an active research and development topic.

Doubling output formats

Another criticism of the semantic web is that it would be much more time-consuming to create and publish content because there would need to be two formats for one piece of data: one for human viewing and one for machines. However, many web applications in development are addressing this issue by creating a machine-readable format upon the publishing of data or the request of a machine for such data. The development of microformats has been one reaction to this kind of criticism. Another argument in defense of the feasibility of semantic web is the likely falling price of human intelligence tasks in digital labor markets, such as Amazon's Mechanical Turk.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Specifications such as eRDF and RDFa allow arbitrary RDF data to be embedded in HTML pages. The GRDDL (Gleaning Resource Descriptions from Dialects of Language) mechanism allows existing material (including microformats) to be automatically interpreted as RDF, so publishers only need to use a single format, such as HTML.

Research activities on corporate applications

The first research group explicitly focusing on the Corporate Semantic Web was the ACACIA team at INRIA-Sophia-Antipolis, founded in 2002. Results of their work include the RDF(S) based Corese search engine, and the application of semantic web technology in the realm of E-learning.[39]

Since 2008, the Corporate Semantic Web research group, located at the Free University of Berlin, focuses on building blocks: Corporate Semantic Search, Corporate Semantic Collaboration, and Corporate Ontology Engineering.[40]

Ontology engineering research includes the question of how to involve non-expert users in creating ontologies and semantically annotated content[41] and for extracting explicit knowledge from the interaction of users within enterprises.

Future of applications

Tim O'Reilly, who coined the term Web 2.0, proposed a long-term vision of the Semantic Web as a web of data, where sophisticated applications manipulate the data web.[42] The data web transforms the World Wide Web from a distributed file system into a distributed database system.[43]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

See also

- AGRIS

- Business semantics management

- Computational semantics

- Calais (Reuters product)

- DBpedia

- Entity–attribute–value model

- EU Open Data Portal

- Hyperdata

- Internet of things

- Linked data

- List of emerging technologies

- Nextbio

- Ontology alignment

- Ontology learning

- RDF and OWL

- Semantic computing

- Semantic Geospatial Web

- Semantic heterogeneity

- Semantic integration

- Semantic matching

- Semantic MediaWiki

- Semantic Sensor Web

- Semantic social network

- Semantic technology

- Semantic Web

- Semantically-Interlinked Online Communities

- Smart-M3

- Social Semantic Web

- Web engineering

- Web resource

- Web science

References

- ^ "XML and Semantic Web W3C Standards Timeline" (PDF). 2012-02-04.

- ^ "World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), "RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised)", 10 Feb. 2004".

- ^ "World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), "OWL Web Ontology Language Overview", W3C Recommendation, 10 Feb. 2004".

- ^ Chung, Seung-Hwa (2018). "The MOUSE approach: Mapping Ontologies using UML for System Engineers". Computer Reviews Journal: 8–29. ISSN 2581-6640.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ أ ب "W3C Semantic Web Activity". World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). November 7, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ "Q&A with Tim Berners-Lee, Special Report". businessweek.com. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ أ ب Berners-Lee, Tim; James Hendler; Ora Lassila (May 17, 2001). "The Semantic Web". Scientific American. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Lee Feigenbaum (May 1, 2007). "The Semantic Web in Action". Scientific American. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ Berners-Lee, Tim; Fischetti, Mark (1999). Weaving the Web. HarperSanFrancisco. chapter 12. ISBN 978-0-06-251587-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Berners-Lee, Tim (May 17, 2001). "The Semantic Web" (PDF). Scientific American. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ Nigel Shadbolt; Wendy Hall; Tim Berners-Lee (2006). "The Semantic Web Revisited" (PDF). IEEE Intelligent Systems. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ^ Ramanathan V. Guha (2013). "Light at the End of the Tunnel". International Semantic Web Conference 2013 Keynote. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Allsopp, John (March 2007). Microformats: Empowering Your Markup for Web 2.0. Friends of ED. p. 368. ISBN 978-1-59059-814-6.

- ^ Artem Chebotko and Shiyong Lu, "Querying the Semantic Web: An Efficient Approach Using Relational Databases", LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, ISBN 978-3-8383-0264-5, 2009.

- ^ Shannon, Victoria (23 May 2006). "A 'more revolutionary' Web". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 26 June 2006.

- ^ Sharma, Akhilesh. "Introducing The Concept Of Web 3.0". Tweak And Trick. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Hodgson, Matthew (9 October 2016). "A decentralized web would give power back to the people online". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Harris, John (7 January 2019). "Together we can thwart the big-tech data grab: here's how". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Brooker, Katrina (29 September 2018). "Exclusive: Tim Berners-Lee tells us his radical new plan to upend the World Wide Web". Fast Company. USA. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Home | inrupt". Inrupt. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Uncertainty Reasoning for the World Wide Web". W3.org. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Lukasiewicz, Thomas; Umberto Straccia (2008). "Managing uncertainty and vagueness in description logics for the Semantic Web" (PDF). Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web. 6 (4): 291–308. doi:10.1016/j.websem.2008.04.001.

- ^ "Semantic Web Standards". W3.org. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "OWL Web Ontology Language Overview". World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). February 10, 2004. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ "Resource Description Framework (RDF)". World Wide Web Consortium.

- ^ Allemang, D.; Hendler, J. (2011). "RDF –The basis of the Semantic Web". Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385965-5.10003-2. ISBN 978-0-12-385965-5.

- ^ "ConverterToRdf - W3C Wiki". W3.org. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Sikos, Leslie F. (2015). Mastering Structured Data on the Semantic Web: From HTML5 Microdata to Linked Open Data. Apress. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4842-1049-9.

- ^ Omar Alonso and Hugo Zaragoza. 2008. Exploiting semantic annotations in information retrieval: ESAIR '08. SIGIR Forum 42, 1 (June 2008), 55–58. DOI:10.1145/1394251.1394262

- ^ Jaap Kamps, Jussi Karlgren, and Ralf Schenkel. 2011. Report on the third workshop on exploiting semantic annotations in information retrieval (ESAIR). SIGIR Forum 45, 1 (May 2011), 33–41. DOI:10.1145/1988852.1988858

- ^ Jaap Kamps, Jussi Karlgren, Peter Mika, and Vanessa Murdock. 2012. Fifth workshop on exploiting semantic annotations in information retrieval: ESAIR '12). In Proceedings of the 21st ACM international conference on information and knowledge management (CIKM '12). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2772–2773. DOI:10.1145/2396761.2398761

- ^ Omar Alonso, Jaap Kamps, and Jussi Karlgren. 2015. Report on the Seventh Workshop on Exploiting Semantic Annotations in Information Retrieval (ESAIR '14). SIGIR Forum 49, 1 (June 2015), 27–34. DOI:10.1145/2795403.2795412

- ^ Kuriakose, John (September 2009). "Understanding and Adopting Semantic Web Technology". Cutter IT Journal. CUTTER INFORMATION CORP. 22 (9): 10–18.

- ^ أ ب ت (2003) "Which semantic web?" in Proc. ACM Conf. on Hypertext and Hypermedia.: 57–66.

- ^ أ ب Ivan Herman (2007). "State of the Semantic Web" in Semantic Days 2007.. Retrieved on July 26, 2007.

- ^ Gärdenfors, Peter (2004). How to make the Semantic Web more semantic. IOS Press. pp. 17–34.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Honkela, Timo; Könönen, Ville; Lindh-Knuutila, Tiina; Paukkeri, Mari-Sanna (2008). "Simulating processes of concept formation and communication". Journal of Economic Methodology.

- ^ "Policy Aware Web Project". Policyawareweb.org. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ (2005) "Towards a Corporate Semantic Web Approach in Designing Learning Systems: Review of the Trial Solutioins Project". International Workshop on Applications of Semantic Web Technologies for E-Learning: 73–76.

- ^ "Corporate Semantic Web - Home". Corporate-semantic-web.de. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ (2012) "Semantic Enrichment by Non-Experts: Usability of Manual Annotation Tools". ISWC'12 - Proceedings of the 11th international conference on The Semantic Web: 165–181.

- ^ Mathieson, S. A. (6 April 2006). "Spread the word, and join it up". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Spivack, Nova (18 September 2007). "The Semantic Web, Collective Intelligence and Hyperdata". novaspivack.typepad.com/nova_spivacks_weblog [This Blog has Moved to NovaSpivack.com]. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

Further reading

- Liyang Yu (December 14, 2014). A Developer's Guide to the Semantic Web,2nd ed. Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-43796-4.

- Aaron Swartz's A Programmable Web: An unfinished Work donated by Morgan & Claypool Publishers after Aaron Swartz's death in January 2013.

- Grigoris Antoniou, Frank van Harmelen (March 31, 2008). A Semantic Web Primer, 2nd Edition. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01242-3.

- Dean Allemang, James Hendler (May 9, 2008). Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist: Effective Modeling in RDFS and OWL. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-0-12-373556-0.

- Pascal Hitzler; Markus Krötzsch; Sebastian Rudolph (August 25, 2009). Foundations of Semantic Web Technologies. CRCPress. ISBN 978-1-4200-9050-5.

- Thomas B. Passin (March 1, 2004). Explorer's Guide to the Semantic Web. Manning Publications. ISBN 978-1-932394-20-7.

- Jeffrey T. Pollock (March 23, 2009). Semantic Web For Dummies. For Dummies. ISBN 978-0-470-39679-7.

External links

| Find more about وب دلالي at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Database entry Q54837 on Wikidata | |

- الصفحات التي تستخدم سمات enclose مهجورة

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- الصفحات بخصائص غير محلولة

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2015

- وب دلالي

- قوالب التكنولوجيا والعلوم التطبيقية

- تكنولوجيات بازغة

- Internet ages

- Knowledge engineering

- Web services