حادثة شيآن

| حادثة شيآن Xi’an Incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من الحرب الأهلية الصينية | |||||||

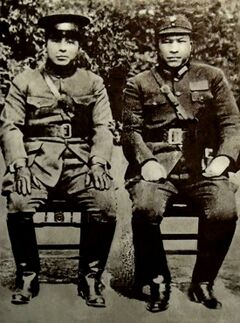

القادة الثلاث المشاركين في حادثة شيآن: Chang Hsüeh-liang, Yang Hucheng, وتشيانگ كاي-شك | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

قالب:Country data Nationalist government |

| ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

قالب:Country data Nationalist government Chiang Kai-shek |

| ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

| 800–1,000 قتيل وجريح | |||||||

| حادثة شيآن | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الصينية التقليدية | 西安事變 | ||||||||

| الحروف المبسطة | 西安事变 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

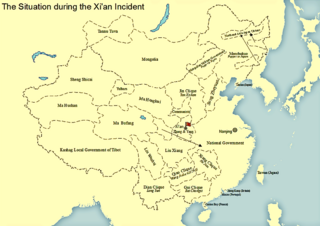

حادثة شيآن Xi'an Incident كانت أزمة سياسية نشبت في شيآن، شآنشي في 1936. حين اِعتُقِل تشيانگ كاي-شك، زعيم الحكومة الوطنية للصين، من قِبل رؤوسيه الجنرالات Chang Hsüeh-liang (Zhang Xueliang) و Yang Hucheng، لإجبار الحزب الوطني الصيني الحاكم (كومنتانگ أو KMT) لتغيير سياساته المتعلقة بإمبراطورية اليابان والحزب الشيوعي الصيني (CCP).[1]

قبل الحادثة، اتبع تشيانگ كاي-شك استراتيجية "التهدئة الداخلية أولاً، ثم المقاومة الخارجية" التي استلزمت تصفية الحزب الشيوعي واسترضاء اليابان للحصول على وقت لعصرنة الصين وجيشها. بعد الحادثة، اصطف تشيانگ مع الشيوعيين ضد اليابانيين. ومع ذلك، بحلول الوقت الذي وصل فيه تشيانگ إلى شيآن في 4 ديسمبر 1936، كانت المفاوضات من أجل جبهة موحدة جارية لمدة عامين.[2] انتهت الأزمة بعد أسبوعين من المفاوضات، في خلالها أُطلِق سراح تشيانگ وأعيد إلى نانجينگ، مصحوباً بـژانگ. ووافق تشيانگ على إنهاء الحرب الأهلية التي كانت مستمرة ضد الحزب الشيوعي وبدأ فعلياً في الإعداد للحرب الوشيكة مع اليابان.[1]

خلفية

الغزو الياباني لمنشوريا

In 1931, the Empire of Japan escalated its aggression against China through the حادثة موكدن. Japanese troops then occupied Northeast China. "Young Marshal" Chang Hsüeh-liang، who had succeeded his father as head of the Fengtian army in that region, was widely criticized for this loss of territory. In response, Chang resigned from his position and went on a tour of Europe.[3]

نزاعات الوطنيين مع الشيوعيين

في أعقاب التجريدة الشمالية في 1928، China was nominally unified under the authority of the Nationalist government in Nanjing. Simultaneously, the Nationalist government violently purged members of the CCP in the Kuomintang, effectively ending the alliance between the two parties.[4] Beginning in the 1930s, the Nationalist government launched a series of campaigns against the CCP. After Zhang returned from his tour of Europe, he was given the task of overseeing these campaigns with his Northeast Army.[5] In the meanwhile, the impending war against Japan led to nationwide unrest and surge of Chinese nationalism.[6] Consequently, the campaigns against the Communist Party were becoming increasingly unpopular. Chiang, fearing the loss of Kuomintang leadership in China, continued the civil war against the CCP despite lacking popular support.[7] Zhang was hoping to reverse the Nationalist policy of prioritizing the purge of Communists, and instead focusing on military preparation against Japanese aggression.[8] After his proposal was rejected by Chiang, the CCP was able to convince Zhang of their commitment to fight the Japanese as a united front, and Zhang began to plot a coup in "great secrecy".[9] By June 1936, the secret agreement between Zhang and the CCP had been successfully settled.[10]

أحداث

In November 1936, Zhang told Chiang to come to Xi'an and talk to troops who did not want to fight the Communist forces any more. After Chiang agreed, Zhang informed Mao Zedong، who called the plan "a masterpiece". On 12 December 1936, bodyguards of Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng stormed the cabin where Chiang was sleeping. Chiang was able to escape but suffered an injury in the process. He was eventually detained by Zhang's troops in the morning.[11][12] A telegram was sent to Nanking (Nanjing) to demand immediate end to civil war against the CCP, and to reorganize the Nationalist government by expelling pro-Japanese factions and adopting an active anti-Japanese stance. As conflicting reports unfolded, the Nationalist government in Nanjing was sent into disarray.[8]

المفاوضات وإطلاق السراح

Many young officers in the Northeast Army demanded Chiang be killed, but this was refused by Zhang as his intention was "only to change his policy".[13] The responses to the coup from high-level Nationalist figures in Nanking were divided. The Military Affairs Commission led by He Yingqin recommended a military campaign against Xi'an, and immediately send a regiment to capture Tongguan.[14] Soong Mei-ling and Kong Xiangxi were strongly in favor of negotiating a settlement to ensure the safety of Chiang.[15]

On 16 December, Zhou Enlai arrived in Xi'an for negotiations, accompanied by fellow CCP diplomat Lin Boqu. At first, Chiang was opposed to negotiating with a CCP delegate, but withdrew his opposition when it became clear that his life and freedom were largely dependent on Communist goodwill towards him. Influencing his decision was also the arrival of Madame Chiang on 22 December, who had travelled to Xi'an hoping to secure his speedy release, fearing military intervention from factions within the Kuomintang. On 24 December, Chiang received Zhou for a meeting, the first time that the two had seen each other since Zhou had left Whampoa Military Academy over ten years earlier. Zhou began the conversation by saying: "In the ten years since we have met, you seem to have aged very little." Chiang nodded and said: "Enlai, you were my subordinate. You should do what I say." Zhou replied that if Chiang would halt the civil war and resist the Japanese instead, the Red Army would willingly accept Chiang's command. By the end of the meeting, Chiang promised to end the civil war, to resist the Japanese together, and to invite Zhou to Nanjing for further talks.[16]

الأعقاب

The Xi'an Incident was a turning point for the CCP. Chiang's leadership over political and military affairs in China was affirmed, while the CCP was able to expand its own strength under the new united front, which later played a factor in the Chinese Communist Revolution.[17]

Chang was kept under house arrest for over 50 years before emigrating to Hawaii in 1993, while Yang was imprisoned and eventually executed on the order of Chiang Kai-shek in 1949, before the Nationalist retreat to Taiwan.[18]

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Taylor 2009, pp. 136–37.

- ^ Paine 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 100.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Garver 1988, p. 5.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 125.

- ^ أ ب Worthing 2017, p. 168.

- ^ Eastman 1986, p. 109-111.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard (2014). China 1945 : Mao's revolution and America's fateful choice (First ed.). New York. p. 29. ISBN 9780307595881.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Eastman 1986, p. 48.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 128.

- ^ Worthing 2017, p. 169.

- ^ Barnouin, Barbara and Yu Changgen. Zhou Enlai: A Political Life. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press: 2006. p. 67

- ^ Garver 1988, p. 78.

- ^ Wakeman 2003, p. 234.

المصادر

| مراجع مكتبية عن حادثة شيآن |

- Cohen, Paul A (2014). History and Popular Memory: The Power of Story in Moments of Crisis. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231166362.

- Eastman, Lloyd E. (1986). The Nationalist Era in China, 1927–1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521385911.

- Garver, John W. (1988). Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937–1945: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195363744.

- Paine, Sarah C. (2012). The Wars for Asia 1911–1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107020696.

- Taylor, Jay (2009). The Generalissimo. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674033382.

- Wakeman, Frederic (2003). Spymaster: Dai Li and the Chinese Secret Service. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520234073.

- Worthing, Peter (2017). General He Yingqin: The Rise and Fall of Nationalist China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107144637.