ويلمنجتون، ديلاوير

ولمنگتن، دلاوير

Wilmington, Delaware | |

|---|---|

| مدينة ولمنگتن | |

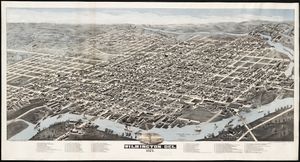

وسط مدينة ولمنگتن ونهر كرستينا | |

| أصل الاسم: مسماة على اسم سپنسر كومپتون, إرل ولمنگتن | |

| الكنية: Corporate Capital of the World, Chemical Capital of the World | |

| الشعار: In the middle of it all[1] | |

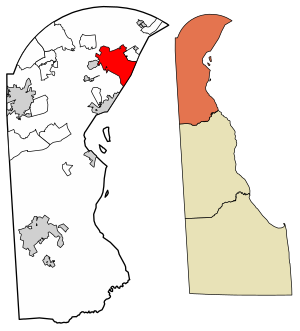

Location within New Castle County | |

| الإحداثيات: 39°44′45″N 75°32′48″W / 39.74583°N 75.54667°W | |

| البلد | الولايات المتحدة |

| الولاية | دلاوير |

| المقاطعة | نيو كاسل |

| تأسست | March 1638 |

| أشهِرت | 1731 |

| Borough Charter | 1739 |

| ميثاق المدينة | March 7, 1832 |

| السمِيْ | سپنسر كومپتون، إرل ولمنگتن الأول |

| الحكومة | |

| • النوع | Council-mayor |

| • Mayor | Mike Purzycki (D) |

| المساحة | |

| • مدينة | 17٫19 ميل² (44٫52 كم²) |

| • البر | 10٫89 ميل² (28٫22 كم²) |

| • الماء | 6٫29 ميل² (16٫30 كم²) |

| المنسوب | 92 ft (28 m) |

| التعداد (2010) | |

| • مدينة | 70٬851 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 70٬166 |

| • الترتيب | US: 483rd |

| • الكثافة | 6٬440٫20/sq mi (2٬486٫54/km2) |

| • العمرانية | 6٬069٬875 (US: 8th)[3] |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 19801-19810, 19850, 19880, 19884-19886, 19890-19899 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 302 |

| FIPS code | 10-77580 |

| GNIS feature ID | 214862[5] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | ci.wilmington.de.us |

Wilmington (Lenape: Paxahakink / Pakehakink)[6] is the largest and most populous city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina River and Brandywine River, near where the Christina flows into the Delaware River. It is the county seat of New Castle County and one of the major cities in the Delaware Valley metropolitan area. Wilmington was named by Proprietor Thomas Penn after his friend Spencer Compton, Earl of Wilmington, who was prime minister during the reign of George II of Great Britain.

As of the 2019 United States Census estimate, the city's population is 70,166.[4] The Wilmington Metropolitan Division, comprising New Castle County, DE, Cecil County, MD and Salem County, NJ, had an estimated 2016 population of 719,887.[7] The Delaware Valley metropolitan area, which includes the cities of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Camden, New Jersey, had a 2016 population of 6,070,500, and a combined statistical area of 7,179,357.[8]

التاريخ

Wilmington is built on the site of Fort Christina and the settlement Kristinehamn,[9] the first Swedish settlement in North America. The modern city also encompasses other Swedish settlements, such as Timmerön / Timber Island (along Brandywine Creek), Sidoland (South Wellington), Strandviken (along the Delaware River near Simonds Garden) and Översidolandet (along the Christina River, near Woodcrest and Ashley Heights).

The area now known as Wilmington was settled by the Lenape (or Delaware Indian) band led by Sachem (Chief) Mattahorn just before Henry Hudson sailed up the Len-api Hanna ("People Like Me River", present Delaware River) in 1609. The area was called "Maax-waas Unk" or "Bear Place" after the Maax-waas Hanna (Bear River) that flowed by (present Christina River). It was called the Bear River because it flowed west to the "Bear People", who are now known as the People of Conestoga or the Susquehannocks.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The Dutch heard and spelled the river and the place as "Minguannan." When settlers and traders from the Swedish South Company under Peter Minuit arrived in March 1638 on the Fogel Grip and Kalmar Nyckel, they purchased Maax-waas Unk from Chief Mattahorn and built Fort Christina at the mouth of the Maax-waas Hanna (which the Swedes renamed the Christina River after Queen Christina of Sweden). The area was also known as "The Rocks", and is located near the foot of present-day Seventh Street. Fort Christina served as the headquarters for the colony of New Sweden which consisted of, for the most part, the lower Delaware River region (parts of present-day Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey), but few colonists settled there.[10][11] Dr. Timothy Stidham (Swedish:Timen Lulofsson Stiddem) was a prominent citizen and doctor in Wilmington. He was born in 1610, probably in Hammel, Denmark and raised in Gothenburg, Sweden. He arrived in New Sweden in 1654 and is recorded as the first physician in Delaware.[12][13]

The most important Swedish governor was Colonel Johan Printz, who ruled the colony under Swedish law from 1643 to 1653. He was succeeded by Johan Rising, who upon his arrival in 1654, seized the Dutch post Fort Casimir, located at the site of the present town of New Castle, which was built by the Dutch in 1651. Rising governed New Sweden until the autumn of 1655, when a Dutch fleet under the command of Peter Stuyvesant subjugated the Swedish forts and established the authority of the Colony of New Netherland throughout the area formerly controlled by the Swedes. This marked the end of Swedish rule in North America.

Beginning in 1664 British colonization began; after a series of wars between the Dutch and English, the area stabilized under British rule, with strong influences from the Quaker communities under the auspices of Proprietor William Penn. A borough charter was granted in 1739 by King George II, which changed the name of the settlement from Willington, after Thomas Willing (the first developer of the land, who organized the area in a grid pattern similar to that of its northern neighbor Philadelphia),[14][15][16] to Wilmington, presumably after Spencer Compton, Earl of Wilmington.

Although during the American Revolutionary War only one small battle was fought in Delaware, British troops occupied Wilmington shortly after the nearby Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. The British remained in the town until they vacated Philadelphia in 1778.

In 1800, Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, a French Huguenot, emigrated to the United States. Knowledgeable in the manufacture of gunpowder, by 1802 DuPont had begun making the explosive in a mill on the Brandywine River north of Brandywine Village and just outside the town of Wilmington.[17] The DuPont company became a major supplier to the U.S. military.[18] Located on the banks of the Brandywine River, the village was eventually annexed by Wilmington city.

The greatest growth in the city occurred during the Civil War. Delaware, though officially remaining a member of the Union, was a border state and divided in its support of both the Confederate and the Union causes. The war created enormous demand for goods and materials supplied by Wilmington including ships, railroad cars, gunpowder, shoes, and other war-related goods.

By 1868, Wilmington was producing more iron ships than the rest of the country combined and it rated first in the production of gunpowder and second in carriages and leather. Due to the prosperity Wilmington enjoyed during the war, city merchants and manufacturers expanded Wilmington's residential boundaries westward in the form of large homes along tree-lined streets. This movement was spurred by the first horsecar line, which was initiated in 1864 along Delaware Avenue.

The late 19th century saw the development of the city's first comprehensive park system. William Poole Bancroft, a successful Wilmington businessman influenced by the work of Frederick Law Olmsted, led the effort to establish open parkland in Wilmington. Rockford Park and Brandywine Park were created due to Bancroft's efforts.

Both World Wars stimulated the city's industries. Industries vital to the war effort – shipyards, steel foundries, machinery, and chemical producers – operated around the clock. Other industries produced such goods as automobiles, leather products, and clothing. In desperate need of workers more and more minorities moved to the north and settled in places like Wilmington. This led to tensions that occasionally boiled over like the Wilmington, Delaware race riot of 1919.

The post-war prosperity again pushed residential development further out of the city. In the 1950s, more people began living in the suburbs of North Wilmington and commuting into the city to work. This was made possible by extensive upgrades to area roads and highways and through the construction of Interstate 95, which cut through several of Wilmington's neighborhoods and accelerated the city's population decline. Urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s cleared entire blocks of housing in the Center City and East Side areas.

The Wilmington riot of 1968, a few days after the April 4 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., became national news. On April 9, Governor Charles L. Terry, Jr. deployed the National Guard and the Delaware State Police to the city at the request of Mayor John Babiarz. Babiarz asked Terry to withdraw the National Guard the following week, but the governor kept them in the city until his term ended in January 1969. This is reportedly the longest occupation of an American city by state forces in the nation's history.[19]

In the 1980s, job growth and office construction were spurred by the arrival of national banks and financial institutions in the wake of the 1981 Financial Center Development Act, which liberalized the laws governing banks operating within the state, and similar laws in 1986. Today, many national and international banks, including Bank of America, Capital One, Chase, and Barclays, have operations in the city, typically credit card operations.

الجغرافيا

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 17.0 ميل مربع (44 km2). Of that, 10.9 ميل مربع (28 km2) is land and 6.2 ميل مربع (16 km2) is water. The total area is 36.25% water.

The city sits at the confluence of the Christina River and the Delaware River, about 33 ميل (53 km) southwest of Philadelphia. Wilmington Train Station, one of the southernmost stops on Philadelphia's SEPTA rail transportation system, is also served by Northeast Corridor Amtrak passenger trains. Wilmington is served by I-95 and I-495 within city limits. In addition, the twin-span Delaware Memorial Bridge, a few miles south of the city, provides direct highway access between Delaware and New Jersey, carrying the I-295 eastern bypass route around Wilmington and Philadelphia, as well as US 40, which continues eastward to Atlantic City, New Jersey.

These transportation links and geographic proximity give Wilmington some of the characteristics of a satellite city to Philadelphia, but Wilmington's long history as Delaware's principal city, its urban core, and its independent value as a business destination makes it more properly considered a small but independent city in the Philadelphia metropolitan area.

Wilmington lies along the Fall Line geological transition from the Mid-Atlantic Piedmont Plateau to the Atlantic Coastal Plain. East of Market Street, and along both sides of the Christina River, the Coastal Plain land is flat, low-lying, and in places marshy. The Delaware River here is an estuary at sea level (with twice-daily high and low tides), providing sea-level access for ocean-going ships.

On the western side of Market Street, the Piedmont topography is rocky and hilly, rising to a point that marks the watershed between the Brandywine River and the Christina River. This watershed line runs along Delaware Avenue westward from 10th Street and Market Street.

These contrasting topography and soil conditions affected the industrial and residential development patterns within the city. The hilly west side was more attractive for the original residential areas, offering springs and sites for mills, better air quality, and fewer mosquitoes.

البلديات المجاورة

المناخ

Wilmington has a warm temperate climate or humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with hot and humid summers, cool to cold winters, and precipitation evenly spread throughout the year. In July, the daily average is 76.8 °F (24.9 °C), with an average 21 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs annually. Summer thunderstorms are common in the hottest months. The January daily average is 32.4 °F (0.2 °C), although temperatures may occasionally reach 10 °F (−12 °C) or 55 °F (13 °C) as fronts move toward and past the area. Snowfall is light to moderate, and variable, with some winters bringing very little of it and others witnessing several major snowstorms; the average seasonal total is 20.2 بوصات (51 cm). Extremes in temperature have ranged from −15 °F (−26 °C) on February 9, 1934, up to 107 °F (42 °C) on August 7, 1918, though both 100 °F (38 °C)+ and 0 °F (−18 °C) readings are uncommon; the last occurrence of each was July 18, 2012 and February 5, 1996, respectively.

| بيانات المناخ لـ ولمنگتن، دلاوير (مطار مقاطعة نيو كاسل)، المعتادة 1981–2010، القصوى 1894–الحاضر | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °ف (°س) | 75 (24) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

97 (36) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

107 (42) |

100 (38) |

98 (37) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

107 (42) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °ف (°س) | 40.2 (4.6) |

43.5 (6.4) |

52.4 (11.3) |

63.5 (17.5) |

73.0 (22.8) |

81.8 (27.7) |

86.1 (30.1) |

84.2 (29.0) |

77.4 (25.2) |

66.2 (19.0) |

55.7 (13.2) |

44.6 (7.0) |

64.1 (17.8) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °ف (°س) | 24.6 (−4.1) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

33.6 (0.9) |

43.0 (6.1) |

52.6 (11.4) |

62.6 (17.0) |

67.6 (19.8) |

66.1 (18.9) |

58.2 (14.6) |

46.1 (7.8) |

37.4 (3.0) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

45.7 (7.6) |

| متوسط الدنيا °ف (°س) | 7.4 (−13.7) |

11.6 (−11.3) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

38.7 (3.7) |

49.9 (9.9) |

56.7 (13.7) |

54.3 (12.4) |

43.7 (6.5) |

32.8 (0.4) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

13.6 (−10.2) |

4.3 (−15.4) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°س) | −14 (−26) |

−15 (−26) |

2 (−17) |

11 (−12) |

30 (−1) |

40 (4) |

48 (9) |

43 (6) |

32 (0) |

23 (−5) |

11 (−12) |

−7 (−22) |

−15 (−26) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار inches (mm) | 3.01 (76) |

2.68 (68) |

3.92 (100) |

3.50 (89) |

3.95 (100) |

3.88 (99) |

4.57 (116) |

3.25 (83) |

4.32 (110) |

3.42 (87) |

3.10 (79) |

3.48 (88) |

43.08 (1٬094) |

| متوسط هطول الثلج inches (cm) | 5.9 (15) |

8.3 (21) |

1.9 (4.8) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

3.4 (8.6) |

20.2 (51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.5 | 9.4 | 10.7 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 9.9 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 117.7 |

| Source: NOAA[20]</ref>[21] | |||||||||||||

الديمغرافيا

| التعداد | Pop. | ملاحظة | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 5٬268 | — | |

| 1830 | 6٬628 | 25٫8% | |

| 1840 | 8٬367 | 26٫2% | |

| 1850 | 13٬979 | 67٫1% | |

| 1860 | 21٬258 | 52٫1% | |

| 1870 | 30٬841 | 45٫1% | |

| 1880 | 42٬478 | 37٫7% | |

| 1890 | 61٬431 | 44٫6% | |

| 1900 | 76٬508 | 24٫5% | |

| 1910 | 87٬411 | 14٫3% | |

| 1920 | 110٬168 | 26�0% | |

| 1930 | 106٬597 | −3٫2% | |

| 1940 | 112٬504 | 5٫5% | |

| 1950 | 110٬356 | −1٫9% | |

| 1960 | 95٬827 | −13٫2% | |

| 1970 | 80٬386 | −16٫1% | |

| 1980 | 70٬195 | −12٫7% | |

| 1990 | 71٬529 | 1٫9% | |

| 2000 | 72٬664 | 1٫6% | |

| 2010 | 70٬851 | −2٫5% | |

| 2019 (تق.) | 70٬166 | [4] | −1�0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] تقدير 2018 Estimate[23] | |||

Government

The Wilmington City Council consists of thirteen members. The council consists of eight members who are elected from geographic districts, four elected at-large and the City Council President. The Council President is elected by the entire city. The Mayor of Wilmington is also elected by the entire city.

The current mayor of Wilmington is Mike Purzycki (D).[24]

| District | Councilperson | Party | - |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Hanifa Shabazz | Democratic | 2017 |

| Treasurer | Velda Jones-Potter | Democratic | 2017 |

| 1 | Nnamdi Chukwuocha | Democratic | 2017 |

| 2 | Ernest "Trippi" Congo II | Democratic | 2017 |

| 3 | Zanthia Oliver | Democratic | 2017 |

| 4 | Michelle Harlee | Democratic | 2017 |

| 5 | Vashun Turner | Democratic | 2017 |

| 6 | Yolanda McCoy | Democratic | 2017 |

| 7 | Robert Williams | Democratic | 2017 |

| 8 | Bud Freel | Democratic | 2017 |

| At-Large | Rysheema Dixon | Democratic | 2017 |

| Sam Guy | Democratic | 2017 | |

| Ciro Adams | Republican | 2017 | |

| Loretta Walsh | Democratic | 2017 |

The Delaware Department of Correction Howard R. Young Correctional Institution, renamed from Multi-Purpose Criminal Justice Facility in 2004 and housing both pretrial and posttrial male prisoners, is located in Wilmington. The prison is often referred to as the "Gander Hill Prison" after the neighborhood it is located in. The prison opened in 1982.[25]

Many Wilmington City workers belong to one of several Locals of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees union.[26]

Economy

Much of Wilmington's economy is based on its status as the most populous and readily accessible city in Delaware, a state that made itself attractive to corporations with business-friendly financial laws and a longstanding reputation for a fair and effective judicial system. Contributing to the economic health of the downtown and Wilmington Riverfront regions has been the presence of Wilmington Station, through which 665,000 people passed in 2009.[27]

Wilmington has become a national financial center for the credit card industry, largely due to regulations enacted by former Governor Pierre S. du Pont, IV in 1981. The Financial Center Development Act of 1981, among other things, eliminated the usury laws enacted by most states, thereby removing the cap on interest rates that banks may legally charge customers. Major credit card issuers such as Barclays Bank of Delaware (formerly Juniper Bank), are headquartered in Wilmington. The Dutch banking giant ING Groep N.V. headquartered its U.S. internet banking unit, ING Direct (now Capital One 360), in Wilmington. Wilmington Trust is headquartered in Wilmington at Rodney Square. Barclays and Capital One 360 have very large and prominent locations along the waterfront of the Christina River. In 1988, the Delaware legislature enacted a law which required a would-be acquirer to capture 85 percent of a Delaware chartered corporation's stock in a single transaction or wait three years before proceeding. This law strengthened Delaware's position as a safe haven for corporate charters during an especially turbulent time filled with hostile takeovers.

Wilmington's other notable industries include insurance (American Life Insurance Company [ALICO], Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Delaware), retail banking (including the Delaware headquarters of: Wilmington Trust (Now a branch of M&T Bank, after Wilmington Trust merged with M&T in 2011), PNC Bank, Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, HSBC, Citizens Bank, Wilmington Savings Fund Society, and Artisans' Bank), and legal services. A General Motors plant was closed in 2009.[28] Wilmington is home to one Fortune 500 company, E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company.[29] Science and Technology are also thriving as companies such as Incyte, Chemours, Corteva and ZipCode call Wilmington home.[30] In addition, the city is the corporate domicile of more than 50% of the publicly traded companies in the United States, and over 60% of the Fortune 500.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Top employers

According to Wilmington's 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[31] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | State of Delaware | 14,199 |

| 2 | Christiana Care Health System | 11,308 |

| 3 | University of Delaware | 4,493 |

| 4 | Amazon (DE Fulfillment Centers) | 4,300 |

| 5 | Nemours (A.I. DuPont Hospital) | 3,795 |

| 6 | DuPont Company | 3,500 |

| 7 | AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP | 2,500 |

| 8 | YMCA of Delaware | 2,469 |

| 9 | Christina School District | 2,390 |

| 10 | Red Clay School District | 2,200 |

| 11 | Delaware Technical Community College | 2,100 |

| 12 | New Castle County Government | 2,000 |

| 13 | M&T Bank (Wilmington Trust Corp.) | 1,900 |

| 14 | Brandywine School District | 1,472 |

| 15 | Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics | 1,410 |

| 16 | Connections Community Support | 1,200 |

| 17 | St. Francis Healthcare | 1,200 |

| 18 | Delaware State University | 1,009 |

| 19 | The Chemours Company | 1,000 |

| 20 | Wilmington VA Medical Center | 980 |

| 21 | Delmarva Power | 898 |

| 22 | AAA | 890 |

| 23 | Blackrock Capital Management, Inc. | 834 |

| 24 | WSFS Bank | 801 |

Sister cities

Wilmington لها six مدن شقيقة، حسب توصيف المدن الشقيقة الدولية: [32]

Fulda, Hesse, Germany

Fulda, Hesse, Germany Kalmar, Sweden

Kalmar, Sweden Olevano sul Tusciano, Salerno, Campania, Italy

Olevano sul Tusciano, Salerno, Campania, Italy Osogbo, Nigeria

Osogbo, Nigeria Watford, Hertfordshire, England, United Kingdom

Watford, Hertfordshire, England, United Kingdom

Partner city

Nemours, Seine-et-Marne, Île-de-France, France

Nemours, Seine-et-Marne, Île-de-France, France

Notable people

See also

- List of Wilmington Mayors

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Wilmington, Delaware

- Sunday Breakfast Mission

- List of tallest buildings in Wilmington, Delaware

References

- ^ Min, Shirley (December 7, 2012). "New signs welcome folks to Delaware's largest city". WHYY-FM News. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Estimates of Resident Population Change and Rankings: July 1, 2014 to July 1, 2015 - United States -- Metropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Wilmington". نظام معلومات الأسماء الجغرافية، المسح الجيولوجي الأمريكي.

- ^ "Lenape Talking Dictionary". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016". 2016 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2017. Archived from the original (CSV) on February 14, 2020. Retrieved Aug 15, 2017.

- ^ "Svenska präster genom tiderna". Geni.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ^ Munroe, John A. (1978), Colonial Delaware: A History, A History of the American colonies, Millwood, New York: KTO Press, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-527-18711-8, OCLC 3933326

- ^ McCormick, Richard P. (1964), New Jersey from Colony to State, 1609–1789, New Jersey Historical Series, 1, Princeton, New Jersey: D. Van Nostrand Co., p. 12, OCLC 477450

- ^ Scharf, J. Thomas (1888), "XXIV. Medicine and medical men", History of Delaware, 1609–1888, Volume 1, Philadelphia: L. J. Richards, p. 471, OCLC 454559306

- ^ Stidham, Jack (2001), "The descendants of Dr. Timothy Stidham", Swedish Colonial News (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Swedish Colonial Society) 2 (5): 16, OCLC 37868632, Archived from the original on June 4, 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20110604051253/http://www.colonialswedes.org/Images/Publications/SCNewsF01.pdf, retrieved on May 14, 2011

- ^ Munroe, John A. (2006), "The Lower Counties on the Delaware", History of Delaware (5th ed.), Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press, p. 57, ISBN 0-87413-947-3, OCLC 68472272, "Originally, the new community was called Willingtown, after Thomas Willing, an English merchant who settled there and began selling town lots in 1731 after marrying the daughter of a Swedish landowner, Andrew Justison"

- ^ Justison, Willing's father-in-law, purchased the land from the family of Samuel Peterson.

- ^ Ferris, Benjamin (1846). "Part III. Chapter II. History of Wilmington" (eBook). A History of the Original Settlements on the Delaware from its Discovery by Hudson to the Colonization under William Penn. Wilmington, Delaware: Wilson & Heald (eBook: The Darlington Digital Library). p. 202. OCLC 124509564.

- ^ "First Powder Mill: 1802". DuPont home, English-US version. Wilmington, Delaware: DuPont. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved January 9, 2010. Archive attempt via WebCitation.org failed May 14, 2011.

- ^ "The DuPont Company". Delaware History Online Encyclopedia. Wilmington, Delaware: Delaware Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Boyer, William W. (2000), "Chapter Three: The Governor as Leader" (eBook), Governing Delaware: Policy Problems In The First State, Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press (eBook: Google), p. 57, ISBN 0-87413-721-7, OCLC 609154858, https://books.google.com/books?id=xN3pzLSQN8IC&lpg=PA57&pg=PA56#v=onepage&q&f=false, retrieved on May 14, 2011

- ^ "NowData: NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved 2019-10-03.

- ^ "Station Name: DE WILMINGTON NEW CASTLE CO AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2019-10-03.[dead link]

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Wilmington mayor, City Council inauguration Tuesday". Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Howard R. Young Correctional Institution". Delaware Department of Correction. State of Delaware. August 18, 2010. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Chalmers, Mike (مايو 14, 2011). "Unions' pact with Wilmington saves 235 jobs". The News Journal. New Castle, Delaware: Gannett. DelawareOnline. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (April 3, 2010), "Delaware transportation: For now, it's a headache on all sides of the tracks", The News Journal (Delawareonline) (New Castle, Delaware: Gannett), https://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/delawareonline/access/2000998191.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Apr+3,+2010&author=ADAM%20TAYLOR&pub=The+News+Journal&desc=For+now,+it's+a+headache+on+all+sides+of+the+tracks&pqatl=google, retrieved on July 7, 2017(يتطلب اشتراك)

- ^ "(Unknown)". Baltimoresun.com. June 2, 2009. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Fortune 500 2012: Delaware". CNN. May 21, 2012. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ Arend, Mark. "Delaware: The Fast Track to Innovation | Site Selection Magazine". Site Selection (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- ^ "City of Wilmington Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). 2019. p. 187. Archived from the original on 2020-08-28. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Wilmington website". Sistercitieswilmington.org. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

Further reading

- Published in the 18th and 19th centuries

- Jedidiah Morse (1797). "Wilmington". The American Gazetteer. Boston, Massachusetts: At the presses of S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews. OL 23272543M.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Charles P. Dare (1877), "Wilmington", Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad guide book, OCLC 37266637

- Published in the 20th century

- Carol Hoffecker: Corporate Capital: Wilmington in the Twentieth Century, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983

External links

- Wilmington, Delaware

- Wilmington Visitors Bureau

- Historic Wilmington Archive

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with dead external links from December 2019

- صفحات تحتوي روابط لمحتوى للمشتركين فقط

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible nickname list

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2015

- Pages using US Census population needing update

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2018

- Pages with empty portal template

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wilmington, Delaware

- Populated places established in 1638

- Port cities and towns of the United States Atlantic coast

- Cities in New Castle County, Delaware

- County seats in Delaware

- Cities in Delaware

- Delaware populated places on the Delaware River

- New Netherland

- Swedish-American history

- Swedish-American culture in Delaware

- New Sweden

- 1638 establishments in the Swedish colonial empire