نادي ليڤرپول

| ||||

| الاسم الكامل | Liverpool Football Club | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| الكنية | الحمر | |||

| تأسس | 3 يونيو 1892[1] | |||

| الملعب | أنفيلد | |||

| السعة | 53,394[2] | |||

| المالك | مجموعة فنواي الرياضية | |||

| الرئيس | توم ورنر | |||

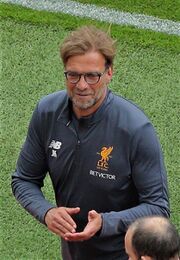

| المدير | يورگن كلوپ | |||

| الدوري | Premier League | |||

| 2018–19 | Premier League, 2nd of 20 | |||

| الموقع الإلكتروني | Club website | |||

|

| ||||

نادي ليفربول Liverpool F.C هو نادي إنجليزي عريق تأسس عام 1892 وهو يلعب في الدرجة الممتازة "البريميير ليج" Premier league بدأت حكاية النادي عندما لم يتفق أعضاء مجلس إدارة نادي ايفرتون الإنجليزي مع مالكي ملعب "أنفيلد" Anfield على قيمة الأجرة، لذلك تركوا الملعب وبقي مالك الملعب في ذلك الملعب وبقى معه ثلاثة من لاعبي الفريق الأول وقرر إنشاء ناد جديد اسمه "ليفربول" وجعل من "أنفيلد" ملعباً للنادي.

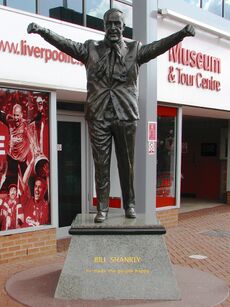

محلياً، حاز النادي على تسعة عشر لقباً للدوري، وثمانية كؤوس للاتحاد الإنگليزي، وتسعة كؤوس للدوري وستة عشر درع الاتحاد الإنجليزي. في المسابقات الدولية، فازت النادي بستة كؤوس لدوري أبطال أوروپا، ثلاثة كؤوس للدوري الأوروپي، أربعة كؤوس للسوپر الأوروپي - جميع الأرقام القياسية الإنگليزية - وكأس العالم لكرة القدم للأندية. أسس النادي نفسه كقوة رئيسية في كرة القدم المحلية والأوروبية في السبعينيات والثمانينيات، عندما قاد بيل شانكلي وبوب پيسلي وجو فاگان وكيني دالگلش فاز النادي بأحد عشر لقباً في الدوري وأربعة كؤوس أوروبية. كما فاز ليفربول بكأسين أوروبيين آخرين في 2005 و 2019 بتدريب رافاييل بينيتيز ويورگن كلوپ، على التوالي؛ قاد الأخير ليفربول إلى لقب الدوري التاسع عشر في 2020، وهو الأول للنادي خلال حقبة الدوري الإنگليزي الممتاز.

يعد ليفربول أحد أكثر الأندية قيمةً والأكثر دعماً في العالم. لدى النادي منافسات طويلة الأمد مع مانشستر يونايتد و إيڤرتون. بقيادة شانكلي، في عام 1964، تغير الفريق من القمصان الحمراء والسراويل البيضاء إلى الملابس الحمراء بالكامل عند اللعب على أرض الديار والذي اعتُمد منذ ذلك الحين. نشيد النادي هو "لن تسير وحدك".

شارك أنصار النادي في مأساتين كبيرتين. أدت كارثة ملعب هيسل، حيث تم الضغط على المشجعين الهاربين بجدار منهار في نهائي كأس أوروبا 1985 في بروكسل، مما أدى إلى 39 حالة وفاة. معظم هؤلاء كانوا إيطاليين من مشجعي نادي يوڤنتوس. تم حظر ليفربول لمدة ست سنوات من المنافسة الأوروبية، مع حظر جميع الأندية الإنجليزية الأخرى لمدة خمس سنوات. أدت كارثة هيلزبره في عام 1989، حيث توفي 97 من أنصار ليفربول بسبب تدافع مقابل سياج محيطي، إلى إزالة المدرجات الدائمة لصالح ملعب بجميع المقاعد في أول مستويين في كرة القدم الإنجليزية. شهدت الحملات المطولة من أجل العدالة مزيداً من التحقيقات واللجان والجماعات المستقلة التي برّأت المشجعين في نهاية المطاف.

التاريخ

تأسس نادي ليفربول بعد نزاع بين لجنة نادي إيڤرتون وجون هولدنگ، رئيس النادي ومالك الملعب في أنفيلد. بعد ثماني سنوات في الملعب، انتقل إيڤرتون إلى گوديسون پارك في عام 1892 وأسس هولدنگ نادي ليفربول لكرة القدم. للعب في الأنفيلد.[3] كان اسمه في الأصل نادي إيڤرتون والملاعب الرياضية المحدودة (نادي إيڤرتون الرياضي باختصار)، وسُمي النادي ليڤرپول. في مارس 1892 وحصل على اعتراف رسمي بعد ثلاثة أشهر، بعد أن رفض الاتحاد الإنگليزي لكرة القدم الاعتراف بالنادي باسم إيڤرتون.[4]

لعب ليفربول أول مباراة له في 1 سبتمبر 1892، بمباراة ودية قبل الموسم ضد روثرهام تاون، التي فازوا بها 7-1. كان فريق ليفربول الذي أقيم ضد روثرهام مؤلفاً بالكامل من لاعبين اسكتلنديين - كان اللاعبون الذين قدموا من اسكتلندا للعب في إنگلترا في تلك الأيام معروفين باسم المدربون الاسكتلنديون. قام المدير جون ماكينا بتجنيد اللاعبين بعد رحلة الكشاف الرياضيون إلى اسكتلندا - لذلك أصبحوا معروفين باسم "فريق ماك". [5] ربح الفريق دوري لانكشاير في أول موسم له وانضم إلى دوري الدرجة الثانية لكرة القدم في بداية موسم 1893-1894. بعد ترقية النادي إلى الدرجة الأولى في عام 1896، وعُين توم واتسون مديراً. وقاد ليفربول إلى لقب الدوري لأول مرة في عام 1901، قبل أن يفوز بها مرة أخرى في عام 1906.[6]

Liverpool reached its first FA Cup Final in 1914, losing 1–0 to Burnley. It won consecutive League championships in 1922 and 1923, but did not win another trophy until the 1946–47 season, when the club won the First Division for a fifth time under the control of ex-West Ham United centre half George Kay.[7] Liverpool suffered its second Cup Final defeat in 1950, playing against Arsenal.[8] The club was relegated to the Second Division in the 1953–54 season.[9] Soon after Liverpool lost 2–1 to non-league Worcester City in the 1958–59 FA Cup, Bill Shankly was appointed manager. Upon his arrival he released 24 players and converted a boot storage room at Anfield into a room where the coaches could discuss strategy; here, Shankly and other "Boot Room" members Joe Fagan, Reuben Bennett, and Bob Paisley began reshaping the team.[10]

The club was promoted back into the First Division in 1962 and won it in 1964, for the first time in 17 years. In 1965, the club won its first FA Cup. In 1966, the club won the First Division but lost to Borussia Dortmund in the European Cup Winners' Cup final.[11] Liverpool won both the League and the UEFA Cup during the 1972–73 season, and the FA Cup again a year later. Shankly retired soon afterwards and was replaced by his assistant, Bob Paisley.[12] In 1976, Paisley's second season as manager, the club won another League and UEFA Cup double. The following season, the club retained the League title and won the European Cup for the first time, but it lost in the 1977 FA Cup Final. Liverpool retained the European Cup in 1978 and regained the First Division title in 1979.[13] During Paisley's nine seasons as manager Liverpool won 20 trophies, including three European Cups, a UEFA Cup, six League titles and three consecutive League Cups; the only domestic trophy he did not win was the FA Cup.[14]

Paisley retired in 1983 and was replaced by his assistant, Joe Fagan.[15] Liverpool won the League, League Cup and European Cup in Fagan's first season, becoming the first English side to win three trophies in a season.[16] Liverpool reached the European Cup final again in 1985, against Juventus at the Heysel Stadium. Before kick-off, Liverpool fans breached a fence that separated the two groups of supporters and charged the Juventus fans. The resulting weight of people caused a retaining wall to collapse, killing 39 fans, mostly Italians. The incident became known as the Heysel Stadium disaster. The match was played in spite of protests by both managers, and Liverpool lost 1–0 to Juventus. As a result of the tragedy, English clubs were banned from participating in European competition for five years; Liverpool received a ten-year ban, which was later reduced to six years. Fourteen Liverpool fans received convictions for involuntary manslaughter.[17]

Fagan had announced his retirement just before the disaster and Kenny Dalglish was appointed as player-manager.[18] During his tenure, the club won another three league titles and two FA Cups, including a League and Cup "Double" in the 1985–86 season. Liverpool's success was overshadowed by the Hillsborough disaster: in an FA Cup semi-final against Nottingham Forest on 15 April 1989, hundreds of Liverpool fans were crushed against perimeter fencing.[19] Ninety-four fans died that day; the 95th victim died in hospital from his injuries four days later, the 96th died nearly four years later, without regaining consciousness, and the 97th, Andrew Devine, died of injuries sustained in the disaster in 2021.[20][21] After the Hillsborough disaster there was a government review of stadium safety. The resulting Taylor Report paved the way for legislation that required top-division teams to have all-seater stadiums. The report ruled that the main reason for the disaster was overcrowding due to a failure of police control.[22]

Liverpool was involved in the closest finish to a league season during the 1988–89 season. Liverpool finished equal with Arsenal on both points and goal difference, but lost the title on total goals scored when Arsenal scored the final goal in the last minute of the season.[23]

Dalglish cited the Hillsborough disaster and its repercussions as the reason for his resignation in 1991; he was replaced by former player Graeme Souness.[24] Under his leadership Liverpool won the 1992 FA Cup Final, but their league performances slumped, with two consecutive sixth-place finishes, eventually resulting in his dismissal in January 1994. Souness was replaced by Roy Evans, and Liverpool went on to win the 1995 Football League Cup Final.[25] While they made some title challenges under Evans, third-place finishes in 1996 and 1998 were the best they could manage, and so Gérard Houllier was appointed co-manager in the 1998–99 season, and became the sole manager in November 1998 after Evans resigned.[26] In 2001, Houllier's second full season in charge, Liverpool won a "treble": the FA Cup, League Cup and UEFA Cup.[27] Houllier underwent major heart surgery during the 2001–02 season and Liverpool finished second in the League, behind Arsenal.[28] They won a further League Cup in 2003, but failed to mount a title challenge in the two seasons that followed.[29][30]

Houllier was replaced by Rafael Benítez at the end of the 2003–04 season. Despite finishing fifth in Benítez's first season, Liverpool won the 2004–05 UEFA Champions League, beating A.C. Milan 3–2 in a penalty shootout after the match ended with a score of 3–3.[31] The following season, Liverpool finished third in the Premier League and won the 2006 FA Cup Final, beating West Ham United in a penalty shootout after the match finished 3–3.[32] American businessmen George Gillett and Tom Hicks became the owners of the club during the 2006–07 season, in a deal which valued the club and its outstanding debts at £218.9 million.[33] The club reached the 2007 UEFA Champions League Final against Milan, as it had in 2005, but lost 2–1.[34] During the 2008–09 season Liverpool achieved 86 points, its then-highest Premier League points total, prior to the record-breaking 2018-19 season, and finished as runners up to Manchester United.[35]

In the 2009–10 season, Liverpool finished seventh in the Premier League and failed to qualify for the Champions League. Benítez subsequently left by mutual consent[36] and was replaced by Fulham manager Roy Hodgson.[37] At the start of the 2010–11 season Liverpool was on the verge of bankruptcy and the club's creditors asked the High Court to allow the sale of the club, overruling the wishes of Hicks and Gillett. John W. Henry, owner of the Boston Red Sox and of Fenway Sports Group, bid successfully for the club and took ownership in October 2010.[38] Poor results during the start of that season led to Hodgson leaving the club by mutual consent and former player and manager Kenny Dalglish taking over.[39] In the 2011–12 season, Liverpool secured a record 8th League Cup success and reached the FA Cup final, but finished in eighth position, the worst league finish in 18 years; this led to the sacking of Dalglish.[40][41] He was replaced by Brendan Rodgers,[42] whose Liverpool team in the 2013–14 season mounted an unexpected title charge to finish second behind champions Manchester City and subsequently return to the Champions League, scoring 101 goals in the process, the most since the 106 scored in the 1895–96 season.[43][44] Following a disappointing 2014–15 season, where Liverpool finished sixth in the league, and a poor start to the following campaign, Rodgers was sacked in October 2015.[45]

Rodgers was replaced by Jürgen Klopp.[46] Liverpool reached the finals of the Football League Cup and UEFA Europa League in Klopp's first season, finishing as runner-up in both competitions.[47] The club finished second in the 2018–19 season with 97 points (surpassing the 86 points gained during the 2008-09 season), losing only one game: a points record for a non-title winning side.[48] Klopp took Liverpool to successive Champions League finals in 2018 and 2019, with the club defeating Tottenham Hotspur 2–0 to win the 2019 UEFA Champions League Final.[49][50] Liverpool beat Flamengo of Brazil in the final 1–0 to win the FIFA Club World Cup for the first time.[51] Liverpool then went on to win the 2019–20 Premier League, winning their first top-flight league title in thirty years.[52] The club set multiple records in the season, including winning the league with seven games remaining making it the earliest any team has ever won the title,[53] amassing a club record 99 points, and achieving a joint-record 32 wins in a top-flight season.[54]

الألوان والشارة

For much of Liverpool's history, its home colours have been all red. When the club was founded in 1892, blue and white quartered shirts were used until the club adopted the city's colour of red in 1896.[3] The city's symbol of the liver bird was adopted as the club's badge (or crest, as it is sometimes known) in 1901, although it was not incorporated into the kit until 1955. Liverpool continued to wear red shirts and white shorts until 1964 when manager Bill Shankly decided to change to an all-red strip.[55] Liverpool played in all red for the first time against Anderlecht, as Ian St John recalled in his autobiography:

He [Shankly] thought the colour scheme would carry psychological impact – red for danger, red for power. He came into the dressing room one day and threw a pair of red shorts to Ronnie Yeats. "Get into those shorts and let's see how you look", he said. "Christ, Ronnie, you look awesome, terrifying. You look 7 ft tall." "Why not go the whole hog, boss?" I suggested. "Why not wear red socks? Let's go out all in red." Shankly approved and an iconic kit was born.[56]

The Liverpool away strip has more often than not been all yellow or white shirts and black shorts, but there have been several exceptions. An all grey kit was introduced in 1987, which was used until the 1991–92 centenary season when it was replaced by a combination of green shirts and white shorts. After various colour combinations in the 1990s, including gold and navy, bright yellow, black and grey, and ecru, the club alternated between yellow and white away kits until the 2008–09 season, when it re-introduced the grey kit. A third kit is designed for European away matches, though it is also worn in domestic away matches on occasions when the current away kit clashes with a team's home kit. Between 2012 and 2015, the kits were designed by Warrior Sports, who became the club's kit providers at the start of the 2012–13 season.[57] In February 2015, Warrior's parent company New Balance announced it would be entering the global football market, with teams sponsored by Warrior now being outfitted by New Balance.[58] The only other branded shirts worn by the club were made by Umbro until 1985, when they were replaced by Adidas, who produced the kits until 1996 when Reebok took over. They produced the kits for 10 years before Adidas made the kits from 2006 to 2012.[59] Nike became the club's official kit supplier at the start of the 2020–21 season.[60]

Liverpool was the first English professional club to have a sponsor's logo on its shirts, after agreeing a deal with Hitachi in 1979.[61] Since then the club has been sponsored by Crown Paints, Candy, Carlsberg and Standard Chartered. The contract with Carlsberg, which was signed in 1992, was the longest-lasting agreement in English top-flight football.[62] The association with Carlsberg ended at the start of the 2010–11 season, when Standard Chartered Bank became the club's sponsor.[63]

The Liverpool badge is based on the city's liver bird symbol, which in the past had been placed inside a shield. In 1977, a red liver bird standing on a football (blazoned as "Statant upon a football a Liver Bird wings elevated and addorsed holding in the beak a piece of seaweed gules") was granted as a heraldic badge by the College of Arms to the English Football League intended for use by Liverpool. However, Liverpool never made use of this badge.[64] In 1992, to commemorate the centennial of the club, a new badge was commissioned, including a representation of the Shankly Gates. The next year twin flames were added at either side, symbolic of the Hillsborough memorial outside Anfield, where an eternal flame burns in memory of those who died in the Hillsborough disaster.[65] In 2012, Warrior Sports' first Liverpool kit removed the shield and gates, returning the badge to what had adorned Liverpool shirts in the 1970s; the flames were moved to the back collar of the shirt, surrounding the number 96 for the number who died at Hillsborough.[66]

Kit suppliers and shirt sponsors

| Period | Kit manufacturer | Shirt sponsor (chest) | Shirt sponsor (sleeve) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973–1979 | Umbro | None | None |

| 1979–1982 | Hitachi | ||

| 1982–1985 | Crown Paints | ||

| 1985–1988 | Adidas | ||

| 1988–1992 | Candy | ||

| 1992–1996 | Carlsberg | ||

| 1996–2006 | Reebok | ||

| 2006–2010 | Adidas | ||

| 2010–2012 | Standard Chartered | ||

| 2012–2015 | Warrior Sports | ||

| 2015–2017 | New Balance | ||

| 2017–2020 | Western Union | ||

| 2020– | Nike | Expedia[67] |

الملعب

Anfield was built in 1884 on land adjacent to Stanley Park. Situated 2 miles (3 km) from Liverpool city centre, it was originally used by Everton before the club moved to Goodison Park after a dispute over rent with Anfield owner John Houlding.[68] Left with an empty ground, Houlding founded Liverpool in 1892 and the club has played at Anfield ever since. The capacity of the stadium at the time was 20,000, although only 100 spectators attended Liverpool's first match at Anfield.[69]

The Kop was built in 1906 due to the high turnout for matches and was called the Oakfield Road Embankment initially. Its first game was on 1 September 1906 when the home side beat Stoke City 1–0.[70] In 1906 the banked stand at one end of the ground was formally renamed the Spion Kop after a hill in KwaZulu-Natal.[71] The hill was the site of the Battle of Spion Kop in the Second Boer War, where over 300 men of the Lancashire Regiment died, many of them from Liverpool.[72] At its peak, the stand could hold 28,000 spectators and was one of the largest single-tier stands in the world. Many stadiums in England had stands named after Spion Kop, but Anfield's was the largest of them at the time; it could hold more supporters than some entire football grounds.[73]

Anfield could accommodate more than 60,000 supporters at its peak and had a capacity of 55,000 until the 1990s, when, following recommendations from the Taylor Report, all clubs in the Premier League were obliged to convert to all-seater stadiums in time for the 1993–94 season, reducing its capacity to 45,276.[74] The findings of the report precipitated the redevelopment of the Kemlyn Road Stand, which was rebuilt in 1992, coinciding with the centenary of the club, and was known as the Centenary Stand until 2017 when it was renamed the Kenny Dalglish Stand. An extra tier was added to the Anfield Road end in 1998, which further increased the capacity of the ground but gave rise to problems when it was opened. A series of support poles and stanchions were inserted to give extra stability to the top tier of the stand after movement of the tier was reported at the start of the 1999–2000 season.[75]

Because of restrictions on expanding the capacity at Anfield, Liverpool announced plans to move to the proposed Stanley Park Stadium in May 2002.[76] Planning permission was granted in July 2004,[77] and in September 2006, Liverpool City Council agreed to grant Liverpool a 999-year lease on the proposed site.[78] Following the takeover of the club by George Gillett and Tom Hicks in February 2007, the proposed stadium was redesigned. The new design was approved by the Council in November 2007. The stadium was scheduled to open in August 2011 and would hold 60,000 spectators, with HKS, Inc. contracted to build the stadium.[79] Construction was halted in August 2008, as Gillett and Hicks had difficulty in financing the £300 million needed for the development.[80] In October 2012, BBC Sport reported that Fenway Sports Group, the new owners of Liverpool FC, had decided to redevelop their current home at Anfield stadium, rather than building a new stadium in Stanley Park. As part of the redevelopment the capacity of Anfield was to increase from 45,276 to approximately 60,000 and would cost approximately £150m.[81] When construction was completed on the new Main stand the capacity of Anfield was increased to 54,074. This £100 million expansion added a third tier to the stand. This was all part of a £260 million project to improve the Anfield area. Jürgen Klopp the manager at the time described the stand as "impressive."[82]

In June 2021, it was reported that Liverpool Council had given planning permission for the club to renovate and expand the Anfield Road stand, boosting the capacity by around 7,000 and taking the overall capacity at Anfield to 61,000. The expansion, which is estimated to cost £60m, was described as "a huge milestone" by managing director Andy Hughes, and would also see rail seating being trialled in the Kop for the 2021–22 Premier League season.[83]

التشجيع

يسمي مشجعي ليفربول انفسهم بالـ Kopites (جماهير الكوب) استنادا إلى طريقة مقاعد الملعب قديما,حيث كان المشجعين يبقون واقفين وليسو جالسين كما الوضع الحالي. يغني المشجعون اغنية "لن تسير وحدك ابداً" في كل مباراة لفريقهم وهي من اشهر الاغنيات على مستوى الفرق الاوروبية والتي يغنيها فرق أخرى كسلتيك الاسكتلندي ولكنها متلازمة لاسم ليفربول دائما.

الكارثتين التان واجهتا مشجعي النادي

- حادثة ملعب هيسل: مات فيها 37 مشجع من نادي يوفنتوس بعد أن انحصر المشجعين في احد الزوايا بسبب مشجعي ليفربول) بعدها قام الاتحاد الاوروبي بمنع الاندية الانجليزية باللعب في البطولات الأوروبية لمدة 6 سنوات.

- حادثة هيلزبرة: في نهائي كأس الاتحاد الانجليزي 1989 ضد فريق نوتينهام فورست حيث ازدحمت المدرجات بالمشجعين بعد ان تم ادخال عدد لم تطيقه المدرجات فتزاحم المشجعين وحصلت الكارثة. بعدها قامت جريدة الصن البريطانية بنقل الخبر بعنوان "الحقيقة" وادعت ان المشجعين قاموا بسرقة الاموات والتبول عليهم ومهاجمة الشرطة تم اثبات كذبها وادعائاتها بعد التحقيقات وقام سكان مدينة ليفربول بمقاطعة الجريدة إلى يومنا الحاضر. وما زال المشجعين يقيمون ذكرى سنوية لموتى هيلزبره كل سنة.

المنافسات

انتصارات شهيرة

في 4 أكتوبر 2020، ضمن الجولة الرابعة من الدوري الإنگليزي الممتاز، هزم أستون ڤيلا ليڤرپول 7-2، في خسارة تاريخية لم يشهدها النادي منذ عام 1963 في مبارته أمام نادي توتنهام.ref>"ليفربول يتلقى 7 اهداف لأول مرة في الدوري الإنجليزي منذ 57 عامًا". جريدة الوفد. 2020-10-04. Retrieved 2020-10-04. </ref>

يشارك اللاعب المصري محمد صلاح كلاعب أساسي مع نادي ليڤرپول بينما يجلس أحمد المحمدي على مقاعد البدلاء، بينما يشارك اللاعب المصري المحترف محمود تريزيجيه ضد التشكيل الأساسي لأستون ڤيلا.[84]

الملكية والمالية

بيع النادي

نجحت مجموعة نيو إنجلند سبورت الأمريكية، في إنهاء صفقة شراء نادى ليفربول الإنجليزى مقابل 300 مليون جنيه إسترلينى.

وقال جون هنرى، المالك الجديد للنادى، في تصريحات للموقع الرسمى لليفربول اليوم، الجمعة، "أشعر بسعادة كبيرة لنجاحنا في إتمام هذه الصفقة".

وكانت المجموعة الأمريكية قد عرضت 300 مليون جنيه إسترلينى لشراء النادى، إلا أن توم هيكس وجورج جيليت مالكال ليفربول السابقين عرقلا صفقة البيع أكثر من مرة بلجوئهما إلى القضاء.

وعانى ليفربول من تراكم الديون عليه أثناء فترة المالكين الأمريكيين، وكان النادى مهددًا بالخضوع للإشراف القضائى وخصم نقاط من رصيده بسبب الديون.

ليفربول في الإعلام

Liverpool featured in the first edition of BBC's Match of the Day, which screened highlights of their match against Arsenal at Anfield on 22 August 1964. The first football match to be televised in colour was between Liverpool and West Ham United, broadcast live in March 1967.[85] Liverpool fans featured in the Pink Floyd song "Fearless", in which they sang excerpts from "You'll Never Walk Alone".[86] To mark the club's appearance in the 1988 FA Cup Final, Liverpool released the "Anfield Rap", a song featuring John Barnes and other members of the squad.[87]

A docudrama on the Hillsborough disaster, written by Jimmy McGovern, was screened in 1996. It featured Christopher Eccleston as Trevor Hicks, who lost two teenage daughters in the disaster, went on to campaign for safer stadiums and helped to form the Hillsborough Families Support Group.[88] Liverpool featured in the 2001 film The 51st State, in which ex-hitman Felix DeSouza (Robert Carlyle) is a keen supporter of the team and the last scene takes place at a match between Liverpool and Manchester United.[89] The club also featured in the 1984 children's television show Scully, about a young boy who tries to gain a trial with Liverpool.[90] The opening scenes of the Doctor Who episode "The Halloween Apocalypse", aired in October 2021, features The Doctor (played by Jodie Whittaker) exiting the TARDIS outside Anfield as she exclaims: "Liverpool? Anfield! Klopp era, classic!".[91]

اللاعبون

First-team squad

- في 1 September 2022[92]

|

|

المعارون

|

|

الاحتياطي والأكاديمية

اللاعبون السابقون

الأرقام القياسية للاعبين

إحصائيات وأرقام

- أكبر نتيجة فوز في دوري ابطال أوروبا 8-0 على بشكتاش التركي عام 2007

- صاحب أكبر عدد مباريات في جميع البطولات أيان كالاهان

- صاحب أكبر عدد مباريات في البطولات الأوروبية جيمي كاراغر

- صاحب أكبر عدد أهداف في جميع البطولات إيان راش

- صاحب أكبر عدد أهداف في البطولات الأوروبية ستيفن جيرارد

- أسرع هاتريك في الدوري الانجليزي روبي فاولر بأربع دقائق و 32 ثانية فقط (00:04:32) ضد ارسنال 1994

هدافو النادي

| # | الاسم | التاريخ | عدد المباريات | عدد الاهداف |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | إيان راش | 1980–1987 & 1988–1996 | 660 | 346 |

| 2 | روجر هانت | 1958–1969 | 492 | 286 |

| 3 | جوردن هودسون | 1925–1936 | 377 | 241 |

| 4 | بيلي ليدل | 1938–1961 | 534 | 228 |

| 5 | روبي فاولر | 1993–2001 & 2006–2007 | 369 | 183 |

| 6 | كيني دالقليش | 1977–1990 | 515 | 172 |

كباتن النادي

Since the establishment of the club in 1892, 45 players have been club captain of Liverpool F.C.[98] Andrew Hannah became the first captain of the club after Liverpool separated from Everton and formed its own club. Alex Raisbeck, who was club captain from 1899 to 1909, was the longest serving captain before being overtaken by Steven Gerrard who served 12 seasons as Liverpool captain starting from the 2003–04 season.[98] The present captain is Jordan Henderson, who in the 2015–16 season replaced Gerrard who moved to LA Galaxy.[94][99]

لاعب الموسم

مسئولو النادي

Liverpool Football Club and Athletic Grounds Limited

Source:[102] نادي ليڤرپول لكرة القدم

Source:[102] |

طاقم التدريب والطب المدير Jürgen Klopp

|

الفخر

Liverpool's first trophy was the Lancashire League, which it won in the club's first season.[5] In 1901, the club won its first League title, while the nineteenth and most recent was in 2020. Its first success in the FA Cup was in 1965. In terms of the number of trophies won, Liverpool's most successful decade was the 1980s, when the club won six League titles, two FA Cups, four League Cups, one Football League Super Cup, five Charity Shields (one shared) and two European Cups.

The club has accumulated more top-flight wins and points than any other English team.[107] Liverpool also has the highest average league finishing position (3.3) for the 50-year period to 2015[108] and second-highest average league finishing position for the period 1900–1999 after Arsenal, with an average league placing of 8.7.[109]

Liverpool is the most successful British club in international football with fourteen trophies, having won the European Cup/UEFA Champions League, UEFA's premier club competition, six times, an English record and only surpassed by Real Madrid and A.C. Milan. Liverpool's fifth European Cup win, in 2005, meant that the club was awarded the trophy permanently and was also awarded a multiple-winner badge.[110][111] Liverpool also hold the English record of three wins in the UEFA Cup, UEFA's secondary club competition.[112] Liverpool also hold the English record of four wins in the UEFA Super Cup.[113] In 2019, the club won the FIFA Club World Cup for the first time, and also became the first English club to win the international treble of Club World Cup, Champions League and UEFA Super Cup.[114][115]

المحلية

الدوري

الكؤوس

- FA Cup

- Football League Cup/EFL Cup

- Football League Super Cup

- Winners (1): 1985–86

- FA Charity Shield/FA Community Shield

الأوروبية

عالمياً

- FIFA Club World Cup

- Winners (1): 2019

الألقاب الصغرى

- Lancashire League: 1

- Winners (1): 1892–93

- Sheriff of London Charity Shield

- Winners (1): 1906

المرتين والثلات مرات

- Doubles:[note 1]

- League and FA Cup (1): 1985–86

- League and League Cup (3): 1981–82, 1982–83, 1983-84

- League and European Cup (2): 1976–77, 1983-84

- League and UEFA Cup (2): 1972–73, 1975–76

- League Cup and European Cup (1): 1980–81

- FA Cup and League Cup (1): 2021–22

- Trebles:[note 1][116]

- League, League Cup and European Cup (1): 1983–84

- FA Cup, League Cup and UEFA Cup (1): 2000–01

المرئيات

| هدف محمد صلاح ليفربول ومانشستر سيتي 16 أكتوبر 2022. |

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ "Happy birthday LFC? Not quite yet..." Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

Liverpool F.C. was born on 3 June 1892. It was at John Houlding's house in Anfield Road that he and his closest friends left from Everton FC, formed a new club.

- ^ "Premier League Handbook 2020/21" (PDF). Premier League. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Liverpool Football Club is formed". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ Graham 1985, p. 14.

- ^ أ ب Kelly 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Graham 1985, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Graham 1985, p. 20.

- ^ Liversedge 1991, p. 14.

- ^ Kelly 1988, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Kelly 1988, p. 57.

- ^ "1965/66: Stan the man for Dortmund". Union of European Football Associations (UEFA). Archived from the original on 10 May 2014.

- ^ Kelly 1999, p. 86.

- ^ Pead 1986, p. 414.

- ^ Kelly 1988, p. 157.

- ^ Kelly 1988, p. 158.

- ^ Cox, Russell & Vamplew 2002, p. 90.

- ^ "On This Day – 29 May 1985: Fans die in Heysel rioting". BBC. 29 May 1985. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ Kelly 1988, p. 172.

- ^ "On This Day – 15 April 1989: Soccer fans crushed at Hillsborough". BBC. 15 April 1989. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ Pithers, Malcolm (22 December 1993). "Hillsborough victim died 'accidentally': Coroner says withdrawal of treatment not to blame". The Independent. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "Hillsborough: Fan injured in stadium disaster dies 32 years later". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 29 July 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "A hard lesson to learn". BBC. 15 April 1999. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ Cowley, Jason (29 March 2009). "The night Football was reborn". The Observer. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Liversedge 1991, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Scully, Mark (22 February 2012). "LFC in the League Cup final: 1995 – McManaman masterclass wins praise from wing wizard Matthews". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Kelly 1999, p. 227.

- ^ "Houllier acclaims Euro triumph". BBC Sport. 16 May 2001. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "Houllier 'satisfactory' after surgery". BBC Sport. 15 October 2001. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- ^ "Liverpool lift Worthington Cup". BBC Sport. 2 March 2003. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "English Premier League 2003–2004: Table". Statto. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "AC Milan 3–3 Liverpool (aet)". BBC Sport. 25 May 2005. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ "Liverpool 3–3 West Ham (aet)". BBC Sport. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "US pair agree Liverpool takeover". BBC Sport. 6 February 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ McNulty, Phil (23 May 2007). "AC Milan 2–1 Liverpool". BBC Sport. Retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ^ "Liverpool's top-flight record". LFC History. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Rafael Benitez leaves Liverpool: club statement". The Daily Telegraph. 3 June 2010. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ "Liverpool appoint Hodgson". Liverpool F.C. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ Gibson, Owen (15 October 2010). "Liverpool FC finally has a new owner after 'win on penalties'". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ "Roy Hodgson exits and Kenny Dalglish takes over". BBC Sport. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Bensch, Bob; Panja, Tariq (16 May 2012). "Liverpool Fires Dalglish After Worst League Finish in 18 Years". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012.

- ^ Ingham, Mike (16 May 2012). "Kenny Dalglish sacked as Liverpool manager". BBC. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ "Liverpool manager Brendan Rodgers to 'fight for his life'". BBC. 1 June 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ Ornstein, David (12 May 2014). "Liverpool: Premier League near-miss offers hope for the future". BBC Sport. BBC. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Goals". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ "Brendan Rodgers: Liverpool boss sacked after Merseyside derby". BBC Sport. 4 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Smith, Ben (8 October 2015). "Liverpool: Jurgen Klopp confirmed as manager on £15m Anfield deal". BBC Sport. BBC. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Liverpool 1–3 Sevilla". BBC. 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Premier League: The numbers behind remarkable title battle" (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). BBC. 12 May 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Liverpool beat Spurs to become champions of Europe for sixth time". BBC. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Real Madrid 3-1 Liverpool" (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). BBC. 26 May 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Firmino winner seals Club World Cup win". BBC. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "Liverpool win Premier League: Reds' 30-year wait for top-flight title ends". BBC. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Sport, Telegraph (22 July 2020). "Liverpool lift the Premier League trophy tonight – these are the records they've broken on the way". The Telegraph (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Champions Liverpool beat Newcastle to finish on 99 points". BBC. 26 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Historical LFC Kits". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ St. John, Ian (9 October 2005). "Shankly: the hero who let me down". The Times. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ "LFC and Warrior announcement". Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ Badenhausen, Kurt (4 February 2015). "New Balance Challenges Nike And Adidas With Entry into Global Soccer Market". Forbes. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Crilly 2007, p. 28.

- ^ "LFC announces multi-year partnership with Nike as official kit supplier from 2020–21". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Dart, James; Tinklin, Mark (6 July 2005). "Has a streaker ever scored?". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ Espinoza, Javier (8 May 2009). "Carlsberg and Liverpool might part ways". Forbes. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Liverpool and Standard Chartered announce sponsorship deal". Standard Chartered Bank. 14 September 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ Phillips, David Llewelyn (Spring 2015). "Badges and 'Crests': The Twentieth-Century Relationship Between Football and Heraldry" (PDF). The Coat of Arms. XI Part I (229): 40,41,46. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Hillsborough". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ "Liverpool kit launch sparks anger among Hillsborough families". BBC Sport. BBC. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Liverpool land Expedia sleeve deal following Western Union departure". www.sportspromedia.com. 19 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Liversedge 1991, p. 112.

- ^ Kelly 1988, p. 187.

- ^ Moynihan 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Liversedge 1991, p. 113.

- ^ Kelly 1988, p. 188.

- ^ Pearce, James (23 August 2006). "How Kop tuned into glory days". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ^ "Club Directory" (PDF). Premier League Handbook Season 2010/11. Premier League. 2010. p. 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "Anfield". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ "Liverpool unveil new stadium". BBC Sport. 17 May 2002. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ Hornby, Mike (31 July 2004). "Reds stadium gets go-ahead". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ "Liverpool get go-ahead on stadium". BBC Sport. 8 September 2006. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ "Liverpool's stadium move granted". BBC. 6 November 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Liverpool stadium 'will be built'". BBC Sport. 17 September 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Smith, Ben (15 October 2012). "Liverpool to redevelop Anfield instead of building on Stanley Park". BBC Sport. BBC. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ "Liverpool's new Main Stand boosts Anfield capacity to 54,000". BBC News. BBC. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ "Liverpool given green light to increase Anfield capacity to 61,000". Sky Sports. Sky UK Limited. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "تريزيجيه قبل مواجهة صلاح: يوم خاص في بلدنا.. وأبو تريكة يوصينا بالمصريين". في الجول. 2020-10-03. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- ^ Kelly 1988, p. 192.

- ^ "The Hillsborough Tragedy". BBC. 16 June 2000. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ "Footballer Barnes for rap return". BBC. 3 March 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ^ "Hillsborough's Sad Legacy". BBC. 14 April 1999. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (18 October 2002). "Formula 51". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Scully". BBC. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Watch: Doctor Who Visits Liverpool As Tardis Lands Outside Anfield In New Series". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ أ ب "First Team". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Shaw, Chris (10 August 2015). "Milner on vice-captain honour and Coutinho class". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ أ ب "Henderson appointed Liverpool captain". Liverpool F.C. 10 July 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Liverpool defender Rhys Williams has joined Championship side Blackpool on a season-long loan deal". Liverpool FC. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Sepp van den Berg wechselt auf Leihbasis zu Schalke 04" (in الألمانية). Schalke 04. 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Williams, Sam. "Marcelo Pitaluga joins Macclesfield on loan". Liverpool FC. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Captains for Liverpool FC since 1892". Liverpool F.C. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ "Steven Gerrard: LA Galaxy confirm deal for Liverpool captain". BBC Sport. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Michael Owen becomes LFC international ambassador". Liverpool F.C. 21 April 2016.

- ^ "Directors". Liverpool FC. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ أ ب "The Liverpool Football Club & Athletic Grounds Limited". Premier League. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish returns to Liverpool on board of directors". BBC. 4 October 2013.

- ^ "LFC appoints director of communications". Liverpool F.C. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013.

- ^ Pearce, James (2 July 2015). "Liverpool FC's transfer committee – who did what to bring new signings to Anfield". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Lynch, David (12 November 2018). "Liverpool get one up over title rivals Manchester City as physio Lee Nobes takes Anfield role". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Pietarinen, Heikki (15 July 2011). "England – First Level All-Time Tables 1888/89-2009/10". Rec. Sport. Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF). Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ "Liverpool lead Manchester United, Arsenal, Everton and Tottenham in Ultimate League". Sky Sports. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Hodgson, Guy (17 December 1999). "How consistency and caution made Arsenal England's greatest team of the 20th century". The Independent. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ Keogh, Frank (26 May 2005). "Why it was the greatest cup final". BBC. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ "Regulations of the UEFA Champions League" (PDF). Union of European Football Associations. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ "New format provides fresh impetus". Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ UEFA.com (14 August 2019). "Liverpool beat Chelsea on penalties to win Super Cup" (in الإنجليزية). Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Ladson, Matt (22 December 2019). "What does Liverpool's Club World Cup victory mean for the rest of their season?". FourFourTwo. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Roberto Firmino scores extra-time winner as Liverpool beat Flamengo to lift Club World Cup". Metro. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Rice, Simon (20 May 2010). "Treble treble: The teams that won the treble". The Independent. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

ملاحظات

ببليوگرافيا

- Cox, Richard; Russell, Dave; Vamplew, Wray (2002). Encyclopedia of British football. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5249-0.

- Crilly, Peter (2007). Tops of the Kops: The Complete Guide to Liverpool's Kits. Trinity Mirror Sport Media. ISBN 978-1-905266-22-7.

- Graham, Matthew (1985). Liverpool. Hamlyn Publishing Group. ISBN 0-600-50254-6.

- Kelly, Stephen F. (1999). The Boot Room Boys: Inside the Anfield Boot Room. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-218907-0.

- Kelly, Stephen F. (1988). You'll Never Walk Alone. Queen Anne Press. ISBN 0-356-19594-5.

- Liversedge, Stan (1991). Liverpool:The Official Centenary History. Hamlyn Publishing Group. ISBN 0-600-57308-7.

- Moynihan, Leo (2009). The Pocket Book of Liverpool. Turnaround Publisher Services. ISBN 978-1-905326-62-4.</ref>

- Pead, Brian (1986). Liverpool A Complete Record. Breedon Books. ISBN 0-907969-15-1.

- Reade, Brian (2009). 43 Years with the Same Bird. Pan. ISBN 978-1-74329-366-9.

وصلات خارجية

Independent websites

- LFCHistory.net Statistics website

- نادي ليڤرپول on BBC Sport: Club news – Recent results and fixtures

- Liverpool at Sky Sports

- Liverpool at Premier League

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- نادي ليفربول

- Football clubs in England

- 1892 establishments in England

- Association football clubs established in 1892

- EFL Cup winners

- Football clubs in Liverpool

- Lancashire League (football)

- Former English Football League clubs

- FA Cup winners

- G-14 clubs

- Multi-sport clubs in the United Kingdom

- Premier League clubs

- FIFA Club World Cup winning clubs

- UEFA Champions League winning clubs

- UEFA Cup winning clubs

- UEFA Super Cup winning clubs

- Shorty Award winners

- أندية كرة قدم تأسست في 1892

- أندية كرة القدم إنجليزية

- بطل كأس الاتحاد الإنجليزي

- أندية كرة القدم الدورى

- أندية كرة قدم فائزة بالكأس

- مجموعة ال 14

- أندية الدوري الإنجليزي الممتاز

- Superleague Formula clubs