جدف رع

| جدف رع Djedefre | |

|---|---|

| Djedefra, Radjedef, Ratoises,[1] Rhampsinit, Rhauosis[2] | |

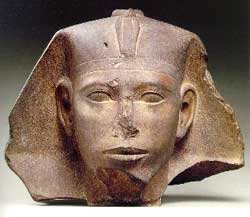

Red granite head of Djedefre from Abu Rawash, Musée du Louvre | |

| فرعون | |

| الحكم | 10 to 14 years, ca. 2575 BC |

| سبقه | Khufu |

| تبعه | Khafra |

| القرينة | Hetepheres II, Khentetka |

| الأنجال | Setka, Baka, Hernet, Neferhetepes, Hetepheres ?, Nikaudjedefre ? |

| الأب | Khufu |

| المدفن | هرم دجدف رع, أبو الهول ?[3] |

| الآثار | هرم دجدف رع |

دجدف رع و يعني أسمه الثابت مثل رع, بعض المؤرخين أطلقوا عليه جددف رع و رع دجدف، هو ابن فرعون مصر العظيم خنوم خو إف وي المعروف بأسم خوفو من زوجته الثانية الليبية، هناك إعتقاد بأنها كانت إحدى محظياته، و يعتبر الحاكم الثالث في الأسرة الرابعة ويمتد حكمه من عام 2558 ق.م. إلى عام 2566 ق.م. أي 8 سنوات.

طريقه إلى العرش

في حقيقة الأمر لم يكن دجدف رع هو المرشح الأول لتولي حكم مصر بعد خوفو، لكنه كان أخوه غير الشقيق كا وعب من زوجته الأولى مريت إت إس، الذي قتل في ظروف غامضة في حياة أبيه خوفو، حيث يعتقد أنه أغتيل في مؤامرة مدبرة، كان أحد أطرافها هو دجدف رع، حتى إن كان لم يكن له دور فيها، فبلا شك أنه كان المنتفع الأول من هذه المؤامرة.

العائلة

بمجرد أن أمن دجدف رع موقعه, على الفور أسرع بالزواج من أخته النصف شقيقة حتب حرس الثانية لمزيد من تأمين عرشه, التي كانت في نفس الوقت أرملة أخوه المغتال كا وعب، وأنجب منها بنت و هينفر حوتب إس، أغلب ظن إنها كانت والدة الفرعون أوسر كاف أول فراعنة الأسرة الخامسة, تزوج دجيدف رع مرة أخرى من خنتت إن كا، وهناك تضارب في أراء المؤرخين بينها وبين حتب حرس الثانية من انها و الدة نفر حوتب إس، لكن من المؤكد من أنها والدة أولاده الذكور الثلاثة ست كا و هر نت و با كا.

العائلة

Djedefre married his brother Kawab's widow, Hetepheres II. She was a sister to both of them, and who perhaps married a third brother of theirs, Khafre, after Djedefre's death.[4] Another queen, Khentetenka is known from statue fragments in the Abu Rowash mortuary temple.[5]

Children with Hetepheres II or Khentetka

- Hornit (“Eldest King's Son of His Body”) known from a statue depicting him and his wife.[6]

- Setka (“Eldest King's Son of His Body; Unique Servant of the King”) known from a scribe statue found in his father's pyramid complex.[7] It is possible that he ruled for a short while after his father's death; an unfinished pyramid at Zawiyet el-Arian was started for a ruler whose name ends in ka; this could have been Setka or Baka.[4]

Children with Hetepheres II

- Neferhetepes (“King's Daughter of His Body; God's Wife”) is known from a statue fragment from Abu Rowash. Until recently, she was believed to be the mother of a pharaoh of the next dynasty, either Userkaf or Sahure.[7]

Possible children with Hetepheres II or Khentetka

- Baka (“Eldest King's Son”) known from a statue base found in Djedefre's mortuary temple, depicting him with his wife Hetepheres. May be the same person as Bikheris.

The French excavation team led by Michel Valloggia found the names of two other possible children of Djedefre in the pyramid complex:

- Nikaudjedefre (“King's Son of His Body”) was buried in Tomb F15 in Abu Rowash; it is possible that he wasn't a son of Djedefre but lived later and his title was only honorary.[7]

- Hetepheres (“King's Daughter of His Body”) was mentioned on a statue fragment.[6]

عهدُه

The Turin King List credits him with a rule of eight years, but the highest known year referred to during this reign appears to be the year of his 11th cattle count. The anonymous year of the 11th count date presumably of Djedefre was found written on the underside of one of the massive roofing-block beams which covered Khufu's southern boat-pits by Egyptian work crews.[8] Miroslav Verner notes that in the work crew's mason marks and inscriptions, "either Djedefra's throne name or his Golden Horus name occur exclusively."[9] Verner writes that the current academic opinion regarding the attribution of this date to Djedefre is disputed among Egyptologists: Rainer Stadelmann, Vassil Dobrev, Peter Jánosi favour dating it to Djedefre whereas Wolfgang Helck, Anthony Spalinger, Jean Vercoutter and W.S. Smith attribute this date to Khufu instead on the assumption "that the ceiling block with the date had been brought to the building site of the boat pit already in Khufu's time and placed in position [only] as late as during the burial of the funerary boat in Djedefre's time."[9]

The German scholar Dieter Arnold, in a 1981 MDAIK paper noted that the marks and inscriptions of the blocks from Khufu's boat pit seem to form a coherent collection relating to the different stages of the same building project realised by Djedefre's crews.[10] Verner stresses that such marks and inscriptions usually pertained to the breaking of the blocks in the quarry, their transportation, their storage and manipulation in the building site itself:[11] "In this context, the attribution of just a single inscription—and what is more, the only one with a date—on all the blocks from the boat pit to somebody other than Djedefra does not seem very plausible."[12]

Verner also notes that the French-Swiss team excavating Djedefre's pyramid have discovered that this king's pyramid was really finished in his reign. According to Michel Vallogia, Djedefre's pyramid largely made use of a natural rock promontory which represented around 45% of its core; the side of the pyramid was 200 cubits long and its height was 125 cubits.[13] The original volume of the monument of Djedefre, hence, approximately equalled that of Menkaura's own pyramid.[14] Therefore, the argument that Djedefre enjoyed a short reign because his pyramid was unfinished is somewhat discredited.[15] This means that Djedefre likely ruled Egypt for a minimum of 11 years if the cattle count was annual, or 22 years if it was biennial; Verner, himself, supports the shorter, 11-year figure and notes that "the relatively few monuments and records left by Djedefra do not seem to favour a very long reign" for this king.[15]

أهم الأحداث خلال فترة حكمه

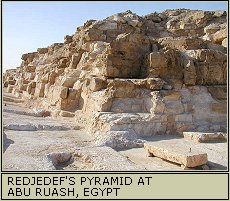

يظن أغلب علماء الأثار بأنه أول من أضاف إلى ألقابه الملكية لقب ابن رع، ذلك دليل على فوز مدرسة أون (هليوپوليس) وكهنتها على حساب كهنة العاصمة منف، واتسمت فترة حكمه بشدة الخلافات والصراعات بينه وبين أخوته الغير أشقاء، على رأسهم أخيه الغير شقيق جدف حور، أيضا مات في عهد أخيه دجدف رع، ووجدت مقبرته بجانب أخيه كاوعب ناقصة وقد نال منها الانتقام. في خلال فترة حكمه بدأ دجدف رع في بناء هرمه في منطقة أبو رواش، حيث كان المخطط لهذا الهرم أن يكون بنفس تصميم هرم من كاو رع الذي بني لاحقاً, لكن لم يكتمل بنائه، حيث أنه من المعتقد أن دجدف رع قد خلع من الملك, ولم يحدد مصيره بعد ذلك هل مات بصورة طبيعية أو قتل أو اختفى في ظروف غامضة، ومن المعروف أن أخوه الغير شقيق خعفرع لم يستكمل بناء هرم دجدف رع من بعده وتركه على حاله. بالفعل كانت فترة مليئة بالصراعات الداخلية في عائلة فرعون، حيث أنها انتهت على الأجح بسقوط دجيدف رع، مع بداية صراع جديد بين اخوانه من زوجة خوفو الثالثة حنو تسن، وهما خعفرع وبا أف رع اللذان تأرجح العرش بينهم حتى دانت أخيرا لخعفرع ومن بعده ابنه من كاو رع.

مجمع الهرم

مقالة مفصلة: هرم جدف رع

مقالة مفصلة: هرم جدف رع

Djedefre continued the move north in the location of pyramids by building his (now ruined) pyramid at Abu Rawash, some 8 كيلومتر (5.0 mi) to the north of Giza. It is the northernmost part of the Memphite necropolis.

While Egyptologists previously assumed that his pyramid at this heavily denuded site was unfinished upon his death, more recent excavations from 1995 to 2005 have established that it was indeed completed.[16] The most recent evidence indicates that its current state is the result of extensive plundering in later periods. The destruction started at the end of the New Kingdom at the latest, and was particularly intense during the Roman and early Christian eras (ح. 2,000 years ago) when a Coptic monastery was built in nearby Wadi Karin, while "the king's statues [were] smashed as late as the 2nd century AD."[16] As a result of Djedefre's pyramid being quarried for its stone, as such, there is little left standing today. It has been proven, moreover, that at the end of the nineteenth century, stone was still being hauled away at the rate of three hundred camel loads a day.[17] The 20th century has also not been kind to this monument – during the last century, it was used as a military camp and its proximity to Cairo exposed it to modern development.[18]

Some believe that the sphinx of his wife, Hetepheres II, which was part of Djedefre's pyramid complex, was the first sphinx created. In 2004, evidence that Djedefre was responsible for the building of the Sphinx at Giza in the image of his father was reported by the French Egyptologist Vassil Dobrev.[19]

Due to the poor condition of Abu Rawash, only small traces of his mortuary complex have been found. Only the rough ground plan of his mud brick mortuary temple was able to be traced—with some difficulty—"in the usual place on the east face of the pyramid."[20] His pyramid causeway proved to run from north to south rather than the more conventional east to west, while no valley temple has been found.[20]

السلم الغامض

المراجع

1- كتاب تاريخ مصر القديمة للكاتب نيقولا جريمال ترجمة ماهر جويجاتي

2- lexicorient.com/e.o/redjedef.htmp

الهامش

- ^ Kim Ryholt: The political Situation in Egypt during the second intermediate Period: c. 1800 - 1550 B.C., Museum Tusculanum Press, Copenhagen 1997, ISBN 87-7289-421-0; William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (The Loeb classical Library)

- ^ Alan B. Lloyd: Herodotus, book II.

- ^ The riddle of the Spinx

- ^ أ ب Dodson & Hilton, p. 55.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton, p. 59.

- ^ أ ب Dodson & Hilton, p. 58.

- ^ أ ب ت Dodson & Hilton, p. 61.

- ^ Verner, Miroslav: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001, p. 375.

- ^ أ ب Verner, p. 375.

- ^ Dieter Arnold, MDAIK 37 (1981), p. 28.

- ^ M. Verner, Baugraffiti der Ptahscepses-Mastaba, Praha (1992). p. 184.

- ^ Verner, p. 376.

- ^ Michel Vallogia, Études sur l'Ancien Empire et la nécropole de Saqqara (Fs Lauer) (1997). p. 418.

- ^ Vallogia, op. cit., p. 418.

- ^ أ ب Verner, p. 377.

- ^ أ ب Clayton, pp. 50-51.

- ^ Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids. London: Atlantic Books. p. 144. ISBN 9781782396802.

- ^ Could Djedefre's Pyramid Be A Solar Temple? Archived 2020-11-19 at the Wayback Machine May 13, 2010, Archaeology News Network.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةauto - ^ أ ب Clayton, p. 50.