الحراك الطلابي في جامعة كلومبيا

شهدت جامعة كلومبيا في مدينة نيويورك، بولاية نيويورك الأمريكية، العديد من الاحتجاجات الطلابية، خاصة التي بدأت في أواخر القرن العشرين.

بداية أعمال الشغب 1811

في منتصف التحضيرات، أُلغي حفل التخرج لعام 1811 بعد رفض تخرج الطالب جون ستيڤنسون إجراء تعديلات على خطاب دعا إلى مزيد من الديمقراطية المباشرة في الحكم الجمهوري.[1] رفض ستيڤنسون تسلمه دبلوماته، وقام الطلبة والجمهور بالذهاب إلى الحفل على المسرح، وهم يطلقون الهسهسة والكلمات الساخرة. أُستدعيت الشرطة، ولم تُمنح درجات ماجستير الآداب، ولم تُلق خططب الوداع.

احتجاجات 1936 ضد النازيين

عام 1936، قاد روبرت بيرك من دفعة 1938 في كلية كلومبيا، جامعة كلومبيا مسيرة خارج قصر الرئيس نيكولاس مري بتلر احتجاجاص على علاقة الجامعة الودية مع النازيين.[2] فُصل بيرك من الجامعة ولم يتم قبوله مرة أخرى. حتى 2018، لم تعتذر الجامعة عن فصله.[3]

احتجاجات 1968

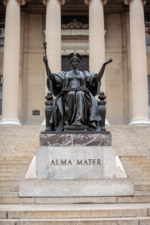

بدأ الطلبة مظاهرة كبرى عام 1968 حول قضيتين رئيسيتين. الأولى هي صالة الألعاب الرياضية التي اقترحتها كلومبيا في مورننگسايد پارك، والتي تعتبر منشأة منفصلة، مع تقييد لدخول السكان السود من ضاحية هارلم المجاورة. أما القضية الثانية فكانت فشل إدارة كلومبيا في الاستقالة من عضويتها المؤسسية في مركز أبحاث الأسلحة التابع للپنتاگون، وهو [معهد تحليلات الدفاع]]. أثناء الاحتجاجات تحصن الطلاب داخل مكتبة لو، قاعة هاملتون، والعديد من المباني الجامعية الأخرى، وأُستدعيت شرطة مدينة نيويورك إلى الحرم الجامعي لاعتقال الطلبة أو طردهم بالقوة.[4][5]

حققت الاحتجاجات اثنين من أهدافها المعلنة. انفصلت كولومبيا عن معهد تحليلات الدفاع وألغت خطط إنشاء الصالة الرياضية المثيرة للجدل، وبدلاً من ذلك بنت الجامعة مركزًا للياقة البدنية تحت الأرض أسفل الطرف الشمالي من الحرم الجامعي. تقول الأسطورة الشائعة أن خطط الصالة الرياضية أُستخدمت في النهاية من قبل جامعة پرنستون لتوسيع مرافقها الرياضية، ولكن بما أن صالة جادوين كانت قد اكتملت بنسبة 50% بالفعل بحلول عام 1966 (عند الإعلان عن صالة الألعاب الرياضية في كلومبيا) فإن من الواضح أن هذا لم يكن صحيحاً.[6] نتيجة للاحتجاجات أوقفت جامعة جلومبيا ما لا يقل عن 30 طالبًا. تخرج العديد من دفعة 68 وعقدوا احتجاجاً مضادة في لو پلازا وقاموا بنزهة في مورننگسايد پارك، المكان الذي بدأت فيه الاحتجاجات.[7] بيان الفراولة، وهو كتاب غير روائي من تأليف ناشط طلابي، جعل جمهورًا أوسع على دراية بالاحتجاجات. أضرت الاحتجاجات بكلومبيا ماليًا حيث اختار العديد من الطلبة المحتملين الالتحاق بجامعات أخرى ورفض بعض الخريجين التبرع بالمال للجامعة.

الاحتجاجات ضد العنصرية والفصل العنصري

في أواخر السبعينيات وأوائل الثمانينيات اندلعت المزيد من الاحتجاجات الطلابية، بما في ذلك الإضراب عن الطعام والمزيد من المتاريس في هاملتون هول وكلية إدارة الأعمال، وكانت تهدف إلى إقناع أمناء الجامعة بسحب جميع استثمارات الجامعة في الشركات التي كان يُنظر إليها على أنها داعمة نشطة أو ضمنية لنظام الفصل العنصري في جنوب أفريقيا.[8]

حدثت تصاعد ملحوظ في الاحتجاجات عام 1978، بعد الاحتفال بالذكرى العاشرة للانتفاضة الطلابية لعام 1968، حيث سار الطلبة واحتشدوا احتجاجًا على استثمارات الجامعات في جنوب إفريقيا. انضمت لجنة مكافحة الاستثمار في جنوب أفريقيا (CAISA) والعديد من المجموعات الطلابية بما في ذلك لجنة العمل الاشتراكي ومنظمة الطلاب السود ومجموعة الطلاب المثليين معًا ونجحت في الضغط من أجل سحب أول جامعة أمريكية لاستثماراتها في جنوب أفريقيا.

ركزت عملية سحب الاستثمارات الأولية (والجزئية) في كلومبيا إلى حد كبير على السندات والمؤسسات المالية المتورطة بشكل مباشر مع نظام جنوب أفريقيا.[9][10]

جاء ذلك في أعقاب حملة استمرت لمدة عام بدأها الطلبة الذين عملوا معًا لمنع تعيين وزير الخارجية الأمريكي السابق هنري كيسنجر كرئيس كرسي موهوب في الجامعة عام 1977.[11]

وبدعم واسع النطاق من المجموعات الطلابية والعديد من أعضاء هيئة التدريس، عقدت لجنة سحب الاستثمار في جنوب أفريقيا دورات تعليمية وعروضًا توضيحية خلال العام ركزت على علاقات الأمناء بالشركات التي تتعامل تجاريًا مع جنوب إفريقيا. قوطعت اجتماعات الأمناء بسبب المظاهرات التي بلغت ذروتها في مايو 1978 عند الاستيلاء على كلية الدراسات العليا لإدارة الأعمال.[12]

كلومبيا غير لائقة

في أوائل عقد 2000، عقد البروفيسور جوسف مسعد دورة اختيارية في جامعة كلومبيا بعنوان السياسة والمجتمعات الفلسطينية والإسرائيلية. شعر الطلبة أن الآراء التي يتبناها في الدورة كانت معادية لإسرائيل وحاول بعضهم تعطيله عن الشرح وطرده.[13]

عام 2004، اجتمع الطلبة مع مجموعة الحرم الجامعي المؤيدة لإسرائيل، مشروع ديڤد، وأنتجوا فيلمًا بعنوان كلومبيا غير لائقة، متهمين مسعد واثنين من الأساتذة الآخرين بترهيب أو معاملة الطلاب ذوي الآراء المؤيدة لإسرائيل بشكل غير عادل. أدى الفيلم إلى قيام رئيس الجامعة بولينگر بتعيين لجنة قامت بتبرئة الأساتذة في ربيع عام 2005.[14] ومع ذلك، انتقد تقرير اللجنة إجراءات التظلم غير الكافية في كلومبيا.[15]

جدل خطبة أحمدي نجاد

توجه كلية الشؤون الدولية والعامة الدعوات إلى رؤساء الدول ورؤساء الحكومات الذين يأتون إلى مدينة نيويورك لافتتاح دورة الخريف للجمعية العامة للأمم المتحدة. عام 2007، كان الرئيس الإيراني محمود أحمدي نجاد أحد المدعوين للتحدث في الحرم الجامعي. قبل أحمدي نجاد دعوته وتحدث في 24 سبتمبر 2007، كجزء من منتدى قادة العالم بجامعة كلومبيا.[16]

أثارة دعوة نجاد الكثير من الجدل. احتشد مئات المتظاهرين في الحرم الجامعي في 24 سبتمبر وتم بث الخطاب نفسه على التلفزيون في جميع أنحاء العالم. حاول رئيس الجامعة لي بولينگر تهدئة الجدل من خلال السماح لأحمدي نجاد بالتحدث، لكن بمقدمة سلبية (قدمها بولينگر شخصيًا). ولم يهدئ هذا من استاءوا من دعوة الزعيم الإيراني إلى الحرم الجامعي.[17] ومع ذلك، خرج طلبة جامعة كلومبيا بأعداد كبيرة للاستماع إلى الخطاب في ساوث لاون. وخرج ما يقدر بنحو 2500 من الطلبة الجامعيين والخريجين لحضور هذه المناسبة التاريخية.

انتقد أحمدي نجاد خلال كلمته سياسات إسرائيل تجاه الفلسطينيين؛ أنكر الهولوكوست؛ قدم ادعاءات حول من بدأ هجمات 11 سبتمبر؛ دافع عن البرنامج النووي الإيراني، منتقدًا سياسة العقوبات التي تتبعها الأمم المتحدة على بلاده؛ وهاجم السياسة الخارجية للولايات المتحدة في الشرق الأوسط. ردًا على سؤال حول معاملة المرأة والمثليين، أكد أن المرأة تحظى بالاحترام في إيران وأنه "في إيران، ليس لدينا مثليون جنسياً كما هو الحال في بلادكم... في إيران، ليس لدينا هذه الظاهرة. لا أعرف من قال لكم هذا".[18] البيان الأخير أثار ضحك الجمهور. اتهم مكتب المدعي العام لمنطقة منهاتن جامعة كلومبيا بقبول منحة مالية من مؤسسة علوي لدعم أعضاء هيئة التدريس "المتعاطفين" مع الجمهورية الإسلامية الإيرانية.[19]

جدل ROTC

Beginning in 1969, during the Vietnam War, the university did not allow the U.S. military to have Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) programs on campus,[20] though Columbia students could participate in ROTC programs at other local colleges and universities.[21][22][23][24] At a forum at the university during the 2008 presidential election campaign, both John McCain and Barack Obama said that the university should consider reinstating ROTC on campus.[23][25][26] After the debate, the president of the university, Lee C. Bollinger, stated that he did not favor reinstating Columbia's ROTC program, because of the military's anti-gay policies. In November 2008, Columbia's undergraduate student body held a referendum on the question of whether or not to invite ROTC back to campus, and the students who voted were almost evenly divided on the issue. ROTC lost the vote (which would not have been binding on the administration, and did not include graduate students, faculty, or alumni) by a fraction of a percentage point.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In April 2010 during Admiral Mike Mullen's address at Columbia, President Lee C. Bollinger stated that the ROTC would be readmitted to campus if the admiral's plans for revoking the don't ask, don't tell policy were successful. In February 2011 during one of three town-hall meetings on the ROTC ban, former Army staff sergeant Anthony Maschek, a Purple Heart recipient for injuries sustained during his service in Iraq, was booed and hissed at by some students during his speech promoting the idea of allowing the ROTC on campus.[27] In April 2011 the Columbia University Senate voted to welcome the ROTC program back on campus.[28] Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus and Columbia University President Lee C. Bollinger signed an agreement to reinstate Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) program at Columbia for the first time in more than 40 years on May 26, 2011. The agreement was signed at a ceremony on board the يوإسإس Iwo Jima, docked in New York for the Navy's annual Fleet Week.[29]

سحب الاستثمارات من السجون الخاصة

In February 2014, after learning that the university had over $10 million invested in the private prison industry, a group of students delivered a letter President Bollinger's office requesting a meeting and officially launching the Columbia Prison Divest (CPD) campaign.[30] اعتبارا من 30 يونيو 2013[تحديث], Columbia held investments in Corrections Corporation of America, the largest private prison company in the United States, as well as G4S, the largest multinational security firm in the world. Students demanded that the university divest these holdings from the industry and instate a ban on future investments in the private prison industry.[31] Aligning themselves with the growing Black Lives Matter movement and in conversation with the heightened attention on race and the system of mass incarceration, CPD student activists hosted events to raise awareness of the issue and worked to involve large numbers of members of the Columbia and West Harlem community in campaign activities.[31] After eighteen months of student driven organizing, the Board of Trustees of Columbia University voted to support the petition for divestment from private prison companies, which was confirmed to student leaders on June 22, 2015.[32] The Columbia Prison Divest campaign was the first campaign to successfully get a U.S. university to divest from the private prison industry.[32]

إضراب التدريس 2021

In January 2021, more than 1000 Columbia University students initiated a tuition strike, demanding that the university lower its tuition rates by 10% amid financial burdens and the move to online classes prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic.[33][34][35] Tuition for undergraduates was at the time $58,920 for an academic year, with the total cost eclipsing $80,000 when expenses including fees, room and board, books and travel were factored in.[36][35] It was the largest tuition strike at an American university in nearly 50 years.[37] Students stated they had won a number of concessions, as the university announced it would freeze tuition, suspend fees on late payments, increase spring financial aid and provide a limited amount of summer grants.[34][37] A university spokesperson, however, stated that the decisions occurred several months prior to the strike.[37] Students also asked the university to end its expansion into and gentrification of West Harlem, defund its university police force, divest from its investments in oil and gas companies, and bargain in good faith with campus unions.[33][37] The university in February 2021 announced that the Board of Trustees had finally formalized its commitment to divest from publicly traded oil and gas companies.[37] The strike had been largely organized by the campus chapter of Young Democratic Socialists of America, which had partnered with other student groups to support the action.[33]

إضراب طلبة الدراسات العليا

Starting in March 2021, members of the Student Workers of Columbia–United Auto Workers, a student employee union, began a strike over issues related to securing a labor contract with the university.[38] The strike ended for a first time on May 13, 2021. Following the end of the strike, on July 3, new leaders for the union were elected who promised to continue to push for a labor contract with the university. A second strike began on November 3, 2021, and concluded on January 7, 2022.

الاحتجاجات المؤيدة لفلسطين 2024

الاحتجاجات الطلابية المؤيدة لفلسطين في جامعة كلومبيا 2024 هي احتجاجا تمستمرة في جامعة كلومبيا بمدينة نيويورك. بدأت في 17 أبريل 2024، عندما أقام الطلبة المؤيدون للفلسطينيين مخيمًا يضم حوالي خمسين خيمة في حرم الجامعة. وتسعى الاحتجاجات إلى وقف الدعم المالي الذي تقدمه جامعة كلومبيا لإسرائيل. في 18 أبريل، أذنت رئيسة الجامعة نعمت شفيق لقسم شرطة نيويورك بدخول الحرم الجامعي وإزالة الطلاب المحتجين في المخيم. لكن تم ترميم المخيم وأدى تصرف الشرطة في جامعة كلومبيا إلى احتجاجات مماثلة في جامعات أخرى.[39]

المصادر

- ^ "Columbia's 1811 Graduation Ceremony Is Known as "The Riotous Commencement"". Columbia College Today (in الإنجليزية). 2020-07-01. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ "Burke's Expulsion: Columbia's Shame". Columbia Daily Spectator. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ "Columbia vs. the Jews, Again". The Weekly Standard (in الإنجليزية). 2018-05-08. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ "Columbia's Radicals of 1968 Hold a Bittersweet Reunion". The New York Times. April 28, 2008.

- ^ "Columbia University – 1968". Columbia.edu. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis. "Gym Groundbreaking Will Be Held Next Month", Columbia Spectator, September 29, 1966.

- ^ George Keller. Columbia College Today (PDF). Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "Disinvestment from South Africa#Higher education endowments"

- ^ "Columbia Senate Supports Selling South African Stocks Selectively". The New York Times. May 7, 1978.

- ^ "Trustees vote for divestiture from backers of S. African government". Columbia Spectator. June 8, 1978.

- ^ "400 sign petition against offering Kissinger faculty post". Columbia Spectator. March 3, 1977.

- ^ "Demonstration at Columbia". New York Daily News. May 2, 1978.

- ^ "Academic Freedom and the Teaching of Palestine-Israel: The Columbia Case, Part II". Journal of Palestine Studies. 34 (4): 75–107. January 1, 2005. doi:10.1525/jps.2005.34.4.75. ISSN 0377-919X. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Ad Hoc Grievance Committee Report". Columbia University. 2005-03-28. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Doob, Gabriella (April 7, 2005). "Columbia report addresses anti-Semitism charges". Brown Daily Herald. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "President Bollinger's Statement About President Ahmadinejad's Scheduled Appearance". Columbia News. September 19, 2007.

- ^ "Candidates Speak Out On Ahmadinejad Visit". CBS News. September 24, 2007.

- ^ "Iran president in NY campus row". BBC News Online. September 25, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Vincent, Isabel (November 22, 2009). "Schools' Iran $ pipeline". New York Post. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ Feith, David J., "Duty, Honor, Country… and Columbia", National Review, September 15, 2008. Archived سبتمبر 17, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Army ROTC at Fordham University Archived نوفمبر 29, 2014 at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 9, 2010

- ^ "U.S. Air Force ROTC – College Life – College". Afrotc.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ أ ب "AFROTC Detachment 560, "The Bronx Bombers", CROSS-TOWN SCHOOLS". Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "NAVY ROTC IN NEW YORK CITY". Archived from the original on June 18, 2013.

- ^ McGurn, William, "A Columbia Marine To Obama: Help!", The Wall Street Journal, September 30, 2008, Page 17.

- ^ "Naval Education and Training Command – NETC". www.netc.navy.mil. Archived from the original on August 2, 2007.

- ^ Karni, Annie, "[1]", New York Post, February 20, 2011.

- ^ [2], "Huff Post College", April 2, 2011.

- ^ "Navy and Columbia Sign NROTC Agreement". Columbia University. May 26, 2011. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ Sestanovich, Clare (March 20, 2015). "Columbia Students to Lee Bollinger: Divest From Prisons Now!". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ أ ب "The New Divestment Movement" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ أ ب Wilfred Chan. "Columbia is first U.S. university to divest from prisons". Cnn.com. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت "Over 1,000 Columbia University students on tuition strike". NBC News (in الإنجليزية). 28 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ^ أ ب Carlin, Dave (22 Jan 2021). "Some Columbia University Students Vow To Ramp Up Tuition Strike".

- ^ أ ب "The Columbia University student strike is about far more than tuition | Indigo Olivier". the Guardian (in الإنجليزية). 2021-02-18. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ^ "Fees, Expenses, and Financial Aid < Columbia College | Columbia University". bulletin.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Columbia Students Wage the Largest Tuition Strike in Nearly 50 Years". In These Times (in الإنجليزية). 26 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ^ Bachman, Brett; Algar, Selim (2021-03-15). "Graduate student workers at Columbia University go on strike". New York Post (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- ^ "Gaza protests: Police raid on Columbia protest ignited campus movement". www.bbc.com. 27 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2017

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ يونيو 2013

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- ثقافة جامعة كلومبيا

- الاحتجاجات الطلابية في ولاية نيويورك

- سياسة طلابية