أزمة الادخار والاقراض

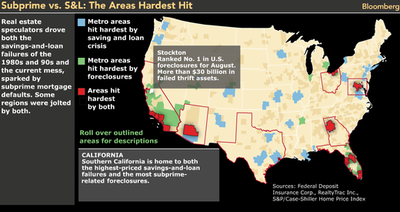

أزمة الادخار والاقراض savings and loan crisis في الثمانينات والتسعينات (تُعرف أيضاً باسم S&L crisis)، كان إفلاس 1.043 من 3.234 جمعية إدخار وإقراض في الولايات المتحدة من عام 1986 إلى 1995: قامت المؤسسة الفدرالية للمدخرات وتأمين القروض (FSLIC) بإغلاق أو حل 296 مؤسسة من عام 1986 حتى 1989 وقامت Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) بإغلاق أو حل 747 مؤسسة من عام 1989 حتى 1995.[1]

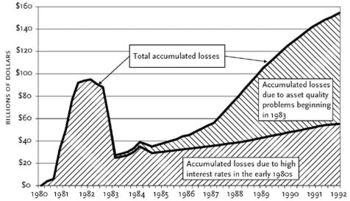

الادخار والاقراض أو "التوفير" هي مؤسسة مالية تقبل ودائع الادخار وتقدم قروض الرهن العقاري والسيارات والقروض الشخصية الأخرى للأفراد (مشروع تعاوني معروف في المملكة المتحدة باسم جمعية البناء). بحلول عام 1995، كانت RTC قد أغلقت 747 مؤسسة مفلسة حول العالم، بإجمالي قيمة دفترية محتملة تتراوح بين 402 و407 مليار دولار. في عام 1996، قدر مكتبة المحاسبة العامة إجمالي التكلفة بمبلغ 160 بليون دولار، تشمل 131.1 بليون دولار مأخوذة من دافعي الضرايب.[2][3] تأسس RTC لحل أزمة المدخرات والقروض.

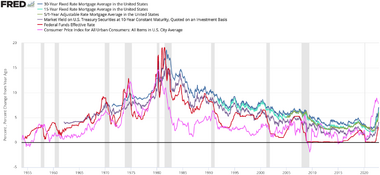

عام 1979، رفع نظام الاحتياط الفدرالي بالولايات المتحدة معدل الخصم الذي تتحمله البنوك الأعضاء في النظام من 9.5% إلى 12% في محاولة للحد من التضخم. أصدر اتحاد جمعيات الادخار والقروض قروضاً طويلة الأجل بأسعار فائدة ثابتة أقل من سعر الفائدة الذي يمكن أن يقترضو به. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تتحمل الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة مسؤولية الودائع التي دفعت معدلات فائدة أعلى من السعر الذي يمكن أن تقترض به. عندما ارتفعت أسعار الفائدة التي يمكنهم الاقتراض بها، لم تتمكن الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة من جذب رؤوس أموال كافية، وعلى سبيل المثال، فإن البنوك التي تحول من الودائع إلى حسابات الادخار، أصبحت متعسرة. وبدلاً من الاعتراف بالإفلاس، سمحت الرقابة التنظيمية المتساهلة لبعض الضمانات بالاستثمار في استراتيجيات الاستثمار عالية المخاطر. كان لهذا تأثير على تمديد الفترة التي كان من المحتمل فيها تعسر المدخرات والقروض من الناحية التقنية. أدت هذه الإجراءات المعاكسة أيضاً إلى زيادة الخسائر الاقتصادية التي تكبدتها الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة بشكل كبير عما كان يمكن تحقيقه لو تم اكتشاف إعسارها في وقت مبكر.[4] ومن أكبر الأمثلة على ذلك الممول تشارلز كيتنگ، الذي دفع 51 مليون دولار كتمويل من خلال عملية "سندات خردة" مايكل ملكن، إلى جمعية لنكولن للمدخرات والقروض التي كان في ذلك الوقت صافي قيمتها السلبي يتجاوز 100 مليون دولار.[5]

آخرون مثل المؤلف والمؤرخ المالي كنيث ج. روبينسون أو رواية الأزمة الذي نُشر عام 2000 من قبل المؤسسة الفدرالية للتأمين على الودائع (FDIC)، قد أعطوا أسباب متعددة لأزمة المدخرات والقروض.[6] مع عدم الالتفات لأهمية الترتيب، حددوا أن بداية ارتفاع التضخم النقدي كانت في أواخر الستينيات وحفزتها برامج الإنفاق المحلية ضمن برامج "المجتمع الكبير" الذي أطلقها الرئيس ليندون جونسون إلى جانب النفقات العسكرية لحرب ڤيتنام التي استمرت حتى أواخر السبعينيات. الجهود المبذولة لإنهاء التضخم المتفشي في أواخر السبعينات وأوائل الثمانينات من خلال رفع أسعار الفائدة أتت بالكساد في أوائل الثمانينيات وبدأت أزمة المدخرات والقروض. رفع القيود عن صناعة المدخرات والقروض، بالإضافة إلى الإمهال التنظيمي، والاحتيال أدى إلى تفاقم الأزمة.[7]

خلفية

الأسباب

سياسة سعر الفائدة للاحتياطي الفدرالي

A major factor contributing to the crisis was the Federal Reserve's response to rampant inflation, marked by Paul Volcker's speech of October 6, 1979, which resulted in a series of short-term interest rate increases. This led to a scenario whereby the short-term costs of funding to S&Ls were higher than the returns they were realizing from many of their mortgage loan portfolios. This situation could not be directly addressed because a large proportion of the loans were fixed-rate mortgages (a problem that is known as an asset-liability mismatch). As the Federal Reserve's policies continued to cause interest rates to rise, this placed even more pressure on S&Ls in late 1979 and into the 1980s, leading to an increased focus on high interest-rate transactions. As a result, fewer people borrowed money from S&Ls which further significantly lowered revenue so the institutions could not offset their losses. According to Zvi Bodie, professor of finance and economics at Boston University School of Management, writing in the St. Louis Federal Reserve Review, "asset-liability mismatch was a principal cause of the Savings and Loan Crisis".[8]

رفع القيود

In the early 1980s Congress passed two laws intended to deregulate the Savings and Loans industry, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 signed by President Jimmy Carter and the Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 signed by President Ronald Reagan. These laws allowed thrifts to offer a wider array of savings products (including adjustable-rate mortgages), but also significantly expanded their lending authority and reduced regulatory oversight.[9] These changes were intended to allow S&Ls to "grow" out of their problems, and as such represented the first time that the government explicitly sought to influence S&L profits as opposed to promoting housing and home ownership.[citation needed] Other changes in thrift oversight included authorizing the use of more lenient accounting rules to report their financial condition, and the elimination of restrictions on the minimum numbers of S&L stockholders. Such policies, combined with an overall decline in regulatory oversight (known as forbearance), would later be cited as factors in the collapse of the thrift industry.[10]

Between 1982 and 1985, S&L assets grew by 56% (compared to growth in commercial banks of 24%). In part, the growth was tilted toward financially weaker institutions which could only attract deposits by offering very high rates and which could only afford those rates by investing in high-yield, risky investments and loans.

The deregulation of S&Ls by the 1980 Act gave the thrifts many of the capabilities of commercial banks without the same regulations as banks, and without explicit FDIC oversight. Savings and loan associations could choose to be under either a state or a federal charter. This decision was made in response to the dramatically increasing interest rates and inflation rates that the S&L market experienced due to vulnerabilities in the structure of the market. Immediately after deregulation of the federally chartered thrifts, state-chartered thrifts rushed to become federally chartered, because of the advantages associated with a federal charter. In response, states such as California and Texas changed their regulations to be similar to federal regulations.[11]

إمهال المدينين

The relatively greater concentration of S&L lending in mortgages, coupled with a reliance on deposits with short maturities for their funding, made savings institutions especially vulnerable to increases in interest rates. As inflation accelerated in the late 1970s and interest rates began to rise rapidly starting in October 1979, many S&Ls began to suffer extensive losses. The rates they had to pay on inter-bank loans (the rate set by the Federal Reserve) increased, and they also had to increase interest rates paid to depositors to attract deposits, but the amount that they earned on long-term fixed-rate mortgages did not change. Losses began to mount.[7] Regulatory agencies responded by granting a forbearance to some requirements, which contributed to the turmoil that the S&L market experienced. Because many insolvent thrifts were allowed to remain open, their financial problems only worsened over time. Moreover, capital standards were reduced both by legislation and by decisions taken by regulators. Federally chartered S&Ls were granted the authority to make new (and ultimately riskier) loans other than residential mortgages.[7] These government policies all prolonged and ultimately exacerbated the crisis.

الإقراض العقاري الطائش

الودائع بالوساطة

الأسباب الرئيسية تبعاً للرابطة الأمريكية لمؤسسات الادخار

الأسباب الرئيسية والدروس المستفادة

In 2005, former bank regulator William K. Black listed a number of lessons that should have been learned from the S&L Crisis that have not been translated into effective governmental action:[12]

- Fraud matters, and control frauds pose unique risks.

- It is important to understand fraud mechanisms. Economists grossly underestimate its prevalence and impact, and prosecutors have difficulties finding it, even without the political pressure from politicians who receive campaign contributions from the banking industry.[13]

- Control fraud can occur in waves created by poorly designed deregulation that creates a criminogenic environment.

- Waves of control fraud cause immense damage.[14]

- Control frauds convert conventional restraints on abuse into aids to fraud.[15]

- Conflicts of interest matter.

- Deposit insurance was not essential to S&L control frauds.

- There are not enough trained investigators in the regulatory agencies to protect against control frauds.

- Regulatory and presidential leadership is important.

- Ethics and social forces are restraints on fraud and abuse.

- Deregulation matters and assets matter.

- The SEC should have a chief criminologist.

- Control frauds defeat corporate governance protections and reforms.

- Stock options increase looting by control frauds.

- The "reinventing government" movement should deal effectively with control frauds.

حالات الإفلاس

في 1980، منح كونگرس الولايات المتحدة جميع صناديق التوفير، بما في ذلك جمعيات الادخار والقروض، صلاحية تقديم قروض استهلاكية وقروض تجارية، وإصدار حسابات معاملات. مصمم لمساعدة صناعة الادخار على الاحتفاظ بقاعدة ودائعها وتحسين ربحيتها، سمح قانون تحرير مؤسسات الإيداع والرقابة النقدية (DIDMCA) لعام 1980 لمؤسسات الادخار بتقديم قروض استهلاكية تصل إلى 20 في المائة من أصولها، وإصدار بطاقات ائتمان، قبول حسابات أمر سحب قابل للتداول من الأفراد والمنظمات غير الربحية، واستثمار ما يصل إلى 20 بالمائة من أصولهم في قروض العقارات التجارية.

بنك هوم ستيت للادخار

مـِدوست فدرال للادخار والقروض

لنكولن للادخار والقروض

سيلڤرادو للادخار والقروض

فضائح

جيم رايت

خمسة كيتنگ

في 17 نوفمبر 1989، بدأت لجنة الأخلاق في مجلس الشيوخ الأمريكي التحقيق في خمسة كيتنگ، ألان كرانستون (د–كاليفورنيا)، دنيس دىكونسيني (د–أريزونا)، جون گلن (د–أوهايو)، جون مكين (ج–أريزونا)، و دونالد ريگل، الابن (د–مشيگن)، الذين كانوا مُتهمين بالتدخل غير الشرعي في عام 1987 لصالح تشارلز كيتنگ، رئيس مجلس ادارة لنكون للادخار والاقراض.

مصرف كيتنگ، لنكون للادخار أفلس في 1989، مكلفاً الحكومة الفدرالية ما يزيد عن 3 مليار دولار وتاركاً 23,000 عميل بسندات بلا قيمة. وفي مطلع ع1990، أدين كيتنگ في محكمتين فدرالية وولائية بعدد من تهم التزوير، والاختلاس و التآمر. وقد قضى في الحبس أربع سنوات ونصف قبل أن تسقط تلك الأحكام في 1996. وفي 1999، اعترف بالذب في عدد أقل من تهم التزوير البرقي و تزوير الإفلاس ، وحُكِم عليه بالوقت الذي قد قضاه سابقاً في الحبس.

إصلاح المؤسسات المالية، التعافي وإنفاذ قانون 1989

التبعات

انظر أيضاً

- أزمة مالية

- صرافة الاحتياطي الجزئي

- قائمة فضائح الشركات

- قائمة إفلاسات أكبر البنوك الأمريكية

- Resolution Trust Corporation

- Subprime mortgage crisis

- قانون الإصلاح الضريبي 1986

- Cottage Savings Association v. Commissioner

- الولايات المتحدة ضد مؤسسة وينستار

مرئيات

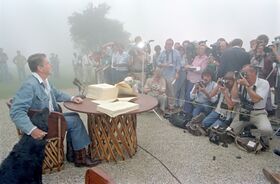

| مسئول جمهوري يخفف من دور الرئيس رونالد ريگان في زيادة حدة أزمة الادخار والاقراض. |

الهوامش

- ^ Curry, T., & Shibut, L. (2000). The Cost of the Savings and Loan Crisis. FDIC Banking Review, 13(2), 26-35.

- ^ "Financial Audit: Resolution Trust Corporation's 1995 and 1994 Financial Statements" (PDF). U.S. General Accounting Office. July 1996. pp. 8, 13, table 3.

- ^ Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan, p. 199. ISBN 978-0-06-074481-6

- ^ Black (2005, p. 5)

- ^ Black (2005, pp. 64–65)

- ^ "The Savings and Loan Crisis and its Relationship to Banking" (PDF). Federal Deposit and Insurance Corporation. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت Robinson, K. J. (2013). The Savings and Loan Crisis. Federalreservehistory.org. Retrieved from http://www.federalreservehistory.org/Events/DetailView/42

- ^ Bodie, Zvi. "On Asset-Liability Matching and Federal Deposit and Pension Insurance." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. July/August 2006, 88(4), pp. 323–29.

- ^ Black (2005, pp. 7, 30–31)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMason - ^ Akerlof, G. A.; Romer, P. M. (1993). "Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit" (PDF). Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1993 (2): 1–73. doi:10.2307/2534564. JSTOR 2534564. S2CID 14896151.

- ^ Black (2005, ch. 10)

- ^ Black (2005, esp. p. 247)

- ^ Black (2005, pp. 248–249)

- ^ Black (2005, p. 250)

المصادر

- Black, William K. (2005). The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70638-3.

- Lowy, Michael (1991). High Rollers: Inside the Savings and Loan Debacle. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-93988-X.

- Mayer, Martin (1992). The Greatest Ever Bank Robbery : The Collapse of the Savings and Loan Industry. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-19152-0.

- Pizzo, Steven; Fricker, Mary; Muolo, Paul (1989). Inside Job: The Looting of America's Savings and Loans. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-050230-7.

- Robinson, Michael A. (1990). Overdrawn: The Bailout of American Savings. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24903-6.

- Tolchin, Martin (1990-09-27). "Legal Scholars Clash Over Neil Bush Actions". New York Times.

- White, Lawrence J. (1991). The S&L Debacle: Public Policy Lessons for Bank and Thrift Regulation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506733-9.

- Cassell, Mark K. (2003). How Governments Privatize: The Politics of Divestment in the United States and Germany. Washington: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 1-58901-008-6.

- Mason, David L. (2001). From Building and Loans to Bail-Outs: A History of the American Savings and Loan Industry, 1831–1989. Ph.D dissertation, Ohio State University, 2001.

- Holland, David S. (1998). When Regulation Was Too Successful – The Sixth Decade of Deposit Insurance. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96356-X.

- Savings and Loan Crisis

- Ely, Bert (2008). "Savings and Loan Crisis". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

وصلات خارجية

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2018

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- أزمة الادخار والاقراض

- أزمات اقتصادية في الولايات المتحدة

- الخدمات المالية في الولايات المتحدة

- بنوك الادخار المتبادل في الولايات المتحدة

- رئاسة رونالد ريگن

- رئاسة جورج بوش الأب

- جدل إدارة رونالد ريگن

- جدل إدارة جورج بوش الأب

- التاريخ الاقتصادي في الثمانينيات

- التاريخ الاقتصادي في التسعينيات