شبكة حقاني

| شبكة حقاني | |

|---|---|

| مشارك في الحرب في أفغانستان (1978-الحاضر)، و الحرب العالمية على الإرهاب | |

| |

| فترة النشاط | 1980s[1]–الحاضر |

| الأيديولوجية | |

| القادة | جلال الدين حقاني (متوفى) سراج الدين حقاني أنس حقاني خليل الرحمن حقاني |

| منطقة العمليات | |

| جزء من | |

| الحلفاء | |

| الخصوم |

|

| المعارك والحروب | الحرب الأفغانية-السوڤيتية الحرب الأهلية الأفغانية (1989-1992) الحرب الأهلية الأفغانية (1992–1996) الحرب الأهلية الأفغانية (1996–2001) الحرب في أفغانستان (2001–الحاضر) عصيان طالبان عملية ضربِ عضب هجوم طالبان 2021[15][16] |

شبكة حقاني Haqqani network هي جماعة متمردة أفغانية تستخدم الحرب الغير متكافئة للقتال ضد الولايات المتحدة - بقيادة قوات الناتو و حكومة أفغانستان. قاد مولوي جلال الدين حقاني وابنه سراج الدين حقاني الجماعة.[17]الشبكة فرع من طالبان.[18][19][20]

بايعت شبكة حقاني طالبان عام 1995،[21] وأصبحت جناحاً مدمجاً بشكل متزايد في المجموعة منذ ذلك الحين.[22]وكان قادة طالبان وحقاني قد نفوا في السابق وجود "الشبكة"، واصفين إياها بأنها لا تختلف عن طالبان..[23]

في الثمانينيات، كانت شبكة حقاني واحدة من أكثر الجماعات المسلحة المعادية للسوڤيات التي تمولها وكالة المخابرات المركزية من قبل رئاسة رونالد ريگان.[24][3] في عام 2012، صنفت الولايات المتحدة شبكة حقاني منظمة إرهابية.[25] في عام 2015، حظرت باكستان أيضاً شبكة حقاني كجزء من خطة العمل الوطنية.[26]

أصل الاسم

كلمة "حقاني" تأتي من دار العلوم الحقانية، المدرسة الإسلامية في پاكستان التي انتظم فيها جلال الدين حقاني.[27]

الأيديولوجية والأهداف

القيم الأصولية لشبكة حقاني قومية ودينية. إنهم متحالفون أيديولوجياً مع طالبان، الذين عملوا على القضاء على النفوذ الغربي وتحويل أفغانستان إلى دولة تتبع الشريعة بشكل صارم. تجسد ذلك في الحكومة التي تشكلت بعد طرد القوات السوڤيتية من أفغانستان. لدى كلتا المجموعتين هدف مشترك يتمثل في تعطيل الجهود العسكرية والسياسية الغربية في أفغانستان وإخراجها من البلاد بشكل دائم.[28] تطالب المجموعة حالياً القوات الأمريكية وقوات التحالف، المكونة في الغالب من دول الناتو، بالانسحاب من أفغانستان وعدم التدخل في السياسة أو الأنظمة التعليمية للدول الإسلامية.[28]

التاريخ

انضم جلال الدين حقاني إلى الحزب الإسلامي الخالص في عام 1978 وأصبح مجاهداً في أفغانستان. تمت رعاية مجموعة حقاني الشخصية من قبل الولايات المتحدة وكالة المخابرات المركزية (CIA) و المخابرات الپاكستانية (ISI) خلال الحرب الأفغانية-السوڤيتية في الثمانينيات.[9][29]

عائلة حقاني

تنحدر عائلة حقاني من جنوب شرق أفغانستان وتنتمي إلى عشيرة ميزي في قبيلة الپشتون زدران.[9][30][31] برز جلال الدين حقاني كقائد عسكري بارز خلال الاحتلال السوفياتي لأفغانستان.[31]مثل گلب الدين حكمتيار، كان حقاني أكثر نجاحاً من قادة المقاومة الآخرين في إقامة علاقات مع الغرباء المستعدين لرعاية مقاومة السوڤييت، بما في ذلك وكالة المخابرات المركزية والمخابرات الپاكستانية (ISI)، والأثرياء العرب المتبرعين من الخليج العربي.

الارتباط بتنظيم القاعدة

قاد جلال الدين حقاني جيش المجاهدين من 1980-1992 وله الفضل في تجنيد مقاتلين أجانب. الجهاديون البارزون اثنان من العرب المعروفين، عبد الله عزام وأسامة بن لادن، وكلاهما بدأ مسيرتهما المهنية كمتطوعين في شبكة حقاني وتدربا على محاربة السوڤييت. تعاونت القاعدة وشبكة حقاني، بمعنى آخر تطورتا معاً، وظلا متشابكين طوال تاريخهما وظلا كذلك حتى يومنا هذا.[32] تعود علاقة شبكة حقاني بـ القاعدة إلى تأسيس القاعدة. الفارق الكبير بين المجموعتين هو أن القاعدة منظمة دولية تسعى لتحقيق أهداف عالمية. في حين أن شبكة حقاني تهتم بشؤون الأفغان وقبائل الپشتون. الاثنان متشابكان في التكتيكات والاستراتيجية والتطرف الإسلامي. أدرك ج. حقاني أهمية "قرارات الشريعة الإسلامية التأسيسية التي أصدرها عزام والتي أعلنت أن الجهاد الأفغاني واجب ملزم على المستوى العالمي والفردي يتحمله جميع المسلمين في جميع أنحاء العالم". على الرغم من أن العديد من القادة المسلمين طلبوا المساعدة من الدول العربية الغنية بالنفط في عام 1978 بعد أن احتلت القوات الشيوعية الأفغانية والقوات السوڤيتية كابول. حقاني هو زعيم المقاومة الإسلامية الأفغاني الوحيد الذي طلب أيضاً مقاتلين مسلمين أجانب، وكان المجموعة الوحيدة التي رحبت بالمقاتلين من خارج المنطقة في صفوفها. وبالتالي "ربطها بنضالات الجهاد الأوسع وولادة العقد التالي لما سيُعرف بالجهاد العالمي."[32][33] إن استخدام شبكة حقاني للممولين السعوديين والمستثمرين العرب الآخرين في مهمته هو الذي يسلط الضوء بوضوح على فهم المجموعات للجهاد العالمي. الفرق الرئيسي بين شبكة حقاني والقاعدة هو مناطق النفوذ التي يسعى كلاهما للسيطرة عليها.[32][33] القاعدة عالمية، وحقاني اقليمية.

تعتقد العديد من المصادر أن جلال الدين حقاني وقواته ساعدوا في هروب القاعدة إلى ملاذات آمنة في پاكستان. بالنظر إلى مدى ارتباط المجموعتين ببعضهما البعض، فهذا ليس امتداداً. من الموثق جيداً أن شبكة حقاني ساعدت في إنشاء ملاذات آمنة. يجادل المحلل پيتر برگن بهذه النقطة في كتابه "المعركة من أجل تورا بورا"[34][35][36][37] بالحكم على الاحتمالات وكمية الأصول العسكرية الأمريكية التي تركز على منطقة صغيرة كهذه، فإن النظرية القائلة بأن شبكة حقاني ساعدت في الهروب تبدو معقولة. بغض النظر عما حدث بالضبط في تلك الجبال، لعبت شبكة حقاني دوراً. وأفعالهم المتمثلة في توفير الملاذ الآمن لـ القاعدة و أسامة بن لادن تظهر قوة الرابطة وبعض الدور أو المعرفة بالقاعدة وهروب بن لادن.

في 26 يوليو 2020، أفاد تقرير الأمم المتحدة أن تنظيم القاعدة لا يزال ينشط في اثنتي عشرة ولاية في أفغانستان وأن زعيمه الظواهري لا يزال متمركزاً في البلاد،[38]وقدر فريق المراقبة التابع للأمم المتحدة أن العدد الإجمالي لمقاتلي القاعدة في أفغانستان يتراوح بين 400 و 600 وأن القيادة على اتصال وثيق بشبكة حقاني، وفي فبراير 2020، التقى الظواهري مع يحيى حقاني، الرئيس الأول. تواصل شبكة حقاني مع القاعدة منذ منتصف عام 2009، لبحث التعاون الجاري.[38]

الارتباط بطالبان

اعترف الجهاديون الأجانب بالشبكة ككيان متميز منذ عام 1994، لكن حقاني لم يكن تابعًا لـ طالبان حتى استولوا على كابول وتولوا السيطرة الفعلية على أفغانستان في عام 1996.[3][39] بعد وصول طالبان إلى السلطة، وافق حقاني على تعيين على مستوى وزاري وزيرا لشؤون العشائر.[40] في أعقاب الغزو الذي قادته الولايات المتحدة لأفغانستان في عام 2001 والإطاحة اللاحقة بحكومة طالبان، فر أبناء حقاني إلى المناطق القبلية الباكستانية الحدودية وأعادوا تجميع صفوفهم للقتال ضد قوات التحالف عبر الحدود.[41]مع تقدم جلال الدين في السن، تولى ابنه سراج الدين مسؤولية العمليات العسكرية.[42]أفاد الصحفي سيد سليم شهزاد أن الرئيس حامد كرزاي دعا في مجلس 2002: ليشغل حقاني الأكبر منصب رئيس الوزراء في محاولة لإدخال طالبان "المعتدلة" في الحكومة. ومع ذلك، رفض جلال الدين العرض.[40]

الولايات المتحدة

وفقاً للقادة العسكريين الأمريكيين، فهي "شبكة العدو الأكثر مرونة" وواحدة من أكبر التهديدات لقوات الناتو بقيادة الولايات المتحدة والحكومة الأفغانية في الحرب الحالية في أفغانستان.[42][43]وهي أيضاً أكثر الشبكات قوة في أفغانستان.[44] في الوقت الحاضر، تعرض الولايات المتحدة مكافأة على المعلومات التي تؤدي إلى اعتقال زعيمهم سراج الدين حقاني بمبلغ 5,000,000 $[45]

إدارة أوباما

في سبتمبر 2012، صنفت إدارة أوباما الشبكة على أنها منظمة إرهابية أجنبية.[46] بعد هذا الإعلان، أصدرت حركة طالبان بياناً قالت فيه إنه "لا يوجد كيان أو شبكة منفصلة في أفغانستان باسم حقاني" وأن جلال الدين حقاني عضو في باكستان ومقرها كيتا شورى، أعلى مجلس قيادة في طالبان..[47]

القيادة

- جلال الدين حقاني - بعد أن كان قائداً في جيش المجاهدين (1980-1992)، تأسست الشبكة تحت حكم حقاني أثناء التمرد ضد القوات السوڤيتية في أفغانستان خلال الثمانينيات. تدرب حقاني نفسه في باكستان خلال السبعينيات، من أجل محاربة رئيس الوزراء محمد داود خان، الذي أطاح بالحاكم السابق (وابن عمه) الملك ظاهر شاه. خلال الغزو السوڤيتي، أصبحت وكالة المخابرات الحكومية الباكستانية وثيقة مع حقاني ومنظمته، مما سمح لهم بأن يصبحوا مستفيداً رئيسياً من الأسلحة والاستخبارات والتدريب الأمريكية. في التسعينيات، وافق حقاني على الانضمام إلى طالبان، ليشغل منصب وزير الداخلية. حاولت الولايات المتحدة إقناع حقاني بقطع العلاقات مع طالبان، وهو ما رفض القيام به. في عام 2005 عندما كان مرجان باثان حاكماً لولاية خوست، اقترب منه حقاني وأراد حواراً مع حكومة حامد كرزاي، لكن لم يستجب الأمريكيون ولا كرزاي لنداءات الحاكم. بعد ذلك، عندما اشتد التمرد من قيادة حامد كرزاي في أفغانستان، اقترب من حقاني وعرض عليه منصب وزير شؤون القبائل في حكومته، وهو ما رفضه حقاني أيضاً لأن الأوان قد فات. منذ ظهور شبكة حقاني، ازدهر حقاني وعائلته من الاتصالات التي أجراها حقاني خلال الحرب الباردة.[48] ذكرت بي بي سي في يوليو 2015 أن جلال الدين حقاني توفي بسبب مرض ودفن في أفغانستان قبل عام على الأقل.[49] وقد ورفضت طالبان هذه التقارير.[50]في 3 سبتمبر 2018، أصدرت حركة طالبان بياناً عبر تويتر أعلنت فيه وفاة حقاني بمرض عضال غير محدد.[51][52]

- سراج الدين حقاني - هو أحد أبناء جلال الدين ويقود حالياً الأنشطة اليومية للشبكة.

- بدر الدين حقاني - شقيق سراج الدين وقائد عمليات التنظيم. قُتل في غارة جوية أمريكية بطائرة بدون طيار في باكستان في 24 أغسطس 2012. ادعى بعض قادة طالبان أن تقارير وفاته صحيحة بينما ادعى آخرون أن التقارير غير دقيقة.[53][54][55][56] ومع ذلك، أكد مسؤولون أمريكيون وباكستانيون وفاته.[57][58] وأكدت طالبان رسمياً وفاة بدر الدين بعد عام.[59]

- سانجين زدران (قُتل في 6 سبتمبر 2013).[60]- وفقاً لوزارة الخارجية الأمريكية، كان ملازماً رفيعاً لسراج الدين وحاكم الظل لـ ولاية پكتيكا في أفغانستان. كان أيضاً أحد خاطفي الجندي الأمريكي بوي برگدال.[53][61][62][63][64]

- نصر الدين حقاني - كان شقيق سراج الدين وممول رئيسي ومبعوث للشبكة. بصفته نجل زوجة جلال الدين العربية، تحدث العربية بطلاقة وسافر إلى المملكة العربية السعودية والإمارات العربية المتحدة لجمع التبرعات.[53][65] قُتل على أيدي مهاجمين مجهولين في إسلام أباد، باكستان، في 11 نوفمبر 2013.[66]

- مولوي أحمد جان (قُتل في 21 نوفمبر 2013)[67] الزعيم الروحي للشبكة الذي كان مسؤولاً أيضاً عن تنظيم بعض أكثر هجمات الشبكة فتكاً في أفغانستان.[67] لقد تعرض لعقوبات الأمم المتحدة[68] في مارس 2010[69] وخدم أيضاً حكومة الملا عمر في حكومة طالبان كوزير فيدرالي للمياه والكهرباء ،[69] قبل أن يتم تعيينه حاكماً لمقاطعة زابل عام 2000.[69]في وقت وفاته، كان يُعتقد أن جان هو النائب الأول لسراج الدين حقاني.[69]

- عبد العزيز عباسين - وفقاً لوزارة الخزانة الأمريكية، فهو "قائد رئيسي في شبكة حقاني" ويشغل منصب "حاكم ظل طالبان في مديرية أرگون، ولاية پكتيكا، أفغانستان."[70]

- الحاج مالي خان - بحسب الناتو، هو "قائد حقاني الكبير في أفغانستان" وعم سراج الدين وبدر الدين.[71][72][73] كما ذكرت إيساف أنه عمل كمبعوث بين بيت الله محسود وحقاني.[74] تم القبض عليه من قبل قوات إيساف في 27 سبتمبر 2011.[72]وقد أطلق سراحه في صفقة تبادل أسرى في نوفمبر 2019.[75]

بعد نشر ويكيليكس في يوليو 2010 لـ 75000 وثيقة سرية، علم الجمهور أن سراج الدين حقاني كان في المستوى الأول من قائمة التأثيرات ذات الأولوية المشتركة لـ القوة الدولية للمساعدة الأمنية - قائمة "القتل أو الأسر".[76]

الأنشطة

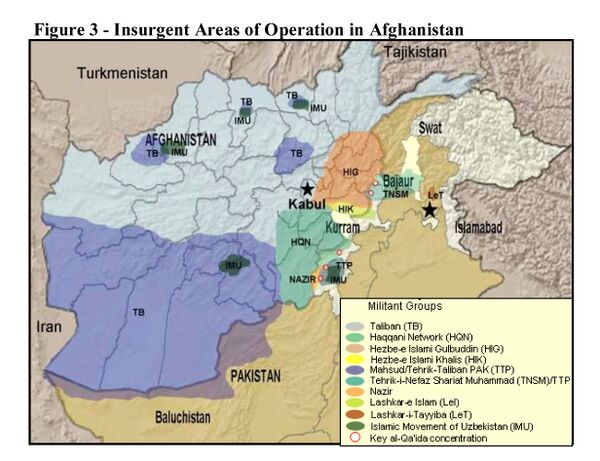

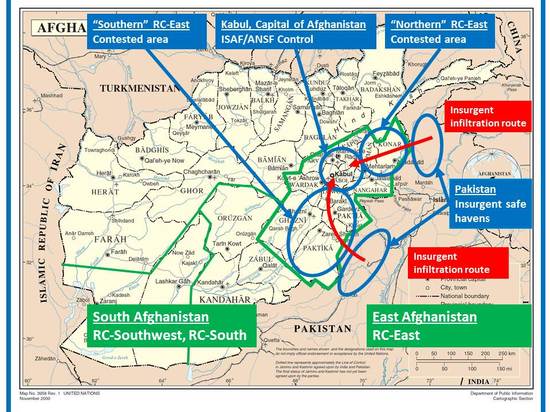

أفاد أناند جوپال من كرستيان ساينس مونيتور، نقلاً عن مصادر أمريكية وأفغانية لم تسمها، في يونيو 2009 أن مقر القيادة في ميرانشاه، مديرية شمالي وزيرستان في مناطق القبائل المدارة اتحادياً الباكستانية على طول الحدود الأفغانية.[5] تعمل من ثلاثة مجمعات على الأقل: معسكر بازار ميرانشاه الذي يحتوي على مدرسة ومرافق حاسب، ومجمع في ضاحية ساراي داربا خيل القريبة ومجمع آخر في داندي داربا خيل، حيث يقيم بعض أفراد عائلة جلال الدين.[30] تنشط الشبكة في المناطق الجنوبية الشرقية لأفغانستان من ولاية پكتيا و ولاية پكتيكا و ولاية خوست و ولاية وردك و ولاية لوگر و ولاية غزنة.[5]في سبتمبر 2011، قال سراج الدين حقاني لـ رويترز إن المجموعة تشعر "بمزيد من الأمان في أفغانستان إلى جانب الشعب الأفغاني."[77]

المنشورات

وقد وُصِف أهل حقاني بأنهم كتّاب بارزون، وقد نشروا عدداً من الكتب بالإضافة إلى التحرير والمساهمة في المجلات، ثلاثة منها، "منبع الجهاد" (نسخة واحدة باللغة الپشتونية وأخرى باللغة العربية) و " نصرت الجهاد (باللغة الأردية)، بلغ عددها أكثر من 1000 صفحة بين عامي 1989 و 1993.[78]

التمويل

يسافر بعض إخوة سراج الدين إلى المنطقة الخليج العربي لجمع الأموال من المتبرعين الأثرياء.[30][53]ذكرت صحيفة نيويورك تايمز في سبتمبر 2011 أن آل حقان أقاموا "وزارة صغيرة" في ميرانشاه مع محاكم ومكاتب ضرائب ومدارس دينية، وأن الشبكة تدير سلسلة من الشركات الأمامية التي تبيع السيارات والعقارات. كما يتلقون أموالاً من عمليات الابتزاز و اختطاف الأطفال وعمليات التهريب في جميع أنحاء شرق أفغانستان.[30] في مقابلة وصف قائد سابق في حقاني الابتزاز بأنه "أهم مصدر تمويل لعائلة حقاني"."[79] وفقاً لأحد شيوخ القبائل في پكتيكا، "يطلب أهل حقاني المال من المقاولين الذين يعملون في بناء الطرق أو البضائع من أصحاب المتاجر ... يدفع شيوخ المنطقة والمقاولون المال للعمال الأفغان، لكن في بعض الأحيان نصف المال سيذهب إلى شعب حقاني."[80]

القوة العسكرية

وبحسب ما ورد يدير حقاني معسكراته التدريبية الخاصة، لتجنيد مقاتليه الأجانب، والسعي للحصول على الدعم المالي واللوجستي بمفرده، من اتصالاته القديمة.[42]تختلف تقديرات أعداد حقاني. تشير مقالة في صحيفة نيويورك تايمز عام 2009 إلى أنه يُعتقد أن لديهم ما بين 4000 إلى 12000 من طالبان تحت إمرتهم بينما تقرير 2011 الصادر عن مركز مكافحة الإرهاب يضع قوتها في حدود 10،000-15،000[3][81]خلال مقابلة في سبتمبر 2011، قال سراج الدين حقاني إن عدد المقاتلين يبلغ 10,000، كما ورد في بعض التقارير الإعلامية، "هو في الواقع أقل من العدد الفعلي."[77] على مدار تاريخها، كانت عمليات الشبكة تتم من قبل وحدات صغيرة شبه مستقلة تم تنظيمها وفقاً للانتماءات القبلية وشبه القبلية في كثير من الأحيان بتوجيه من قادة حقاني وبدعمٍ لوجستي من قادة حقاني.[3]

تتكون الشبكة على نطاق واسع من أربع مجموعات: أولئك الذين كانوا مع جلال الدين منذ الجهاد في الحقبة السوڤڤيتية، وأولئك من لويه پکتيا الذين انضموا منذ عام 2001، وأولئك من شمال وزيرستان الذين انضموا في السنوات الأخيرة، والأجانب مسلحون من أصول عربية وشيشانية وأوزبكية في المقام الأول. يتم شغل الأدوار القيادية في الغالب بأفراد من المجموعة الأولى في حين أن المبتدئين من لويه پکتيا وغير الپشتون ليسوا جزءاً من هذه الدائرة الداخلية.[30][31]

كانت شبكة حقاني رائدة في استخدام الهجمات الانتحارية في أفغانستان وتميل إلى استخدام القاذفات الأجنبية في الغالب بينما تميل طالبان إلى الاعتماد على السكان المحليين في الهجمات.[5]وتزود الشبكة، بحسب ناشونال جورنال، بالكثير من كلورات الپوتاسيوم المستخدمة في القنابل التي تستخدمها حركة طالبان في أفغانستان. كذلك، تستخدم قنابل الشبكة أجهزة إطلاق عن بعد أكثر تطوراً من تلك التي تستخدم في تنشيط الضغط المطلي بالضغط المستخدمة في أماكن أخرى في أفغانستان. وقال سراج الدين حقاني لـ MSNBC في أبريل 2009 إن مقاتليه "حصلوا على التكنولوجيا الحديثة التي كنا نفتقدها، وأتقننا أساليب جديدة ومبتكرة في صنع القنابل والمتفجرات."[82]

في أواخر عام 2011، بدأ تداول كتاب من 144 صفحة منسوباً إلى سراج الدين حقاني في أفغانستان وپاكستان. يصف كتاب نيوزويك بأنه "دليل للمقاتلين والإرهابيين"، ويفصل الكتاب المكتوب بلغة الپشتو تعليمات حول إنشاء خلية جهادية، وتلقي التمويل والتجنيد والتدريب. ينصح الكتيب المجندين بأن إذن الوالدين ليس ضرورياً للجهاد، وأنه يجب سداد جميع الديون قبل الانضمام، وأن التفجيرات الانتحارية وقطع الرؤوس مسموح بها في الإسلام.[83]

الهجمات والهجمات المزعومة

- 14 January 2008: The 2008 Kabul Serena Hotel attack is thought to have been carried out by the network.[42]

- March 2008: Kidnapping of British journalist Sean Langan was blamed on the network.[84]

- 27 April 2008: Assassination attempts on Hamid Karzai.[5]

- 7 July 2008: US intelligence blamed the network for 2008 Indian embassy bombing in Kabul.[85]

- 10 November 2008: The Kidnapping of David Rohde was blamed on Sirajuddin Haqqani.[86]

- 30 December 2009: Camp Chapman attack is thought to have been carried out by the network.[87]

- 18 May 2010: May 2010 Kabul bombing was allegedly carried out by the network.[88]

- 19 February 2011: Kabul Bank in Jalalabad, Afghanistan.[89]

- 28 June 2011: According to ISAF, elements of the Haqqani network provided "material support" in the 2011 attack on the Hotel Inter-Continental in Kabul.[90] The Taliban claimed responsibility.[91]

- 10 September 2011: A massive truck bomb exploded outside Combat Outpost Sayed Abad in Wardak province, Afghanistan, killing five Afghans, including four civilians, and wounding 77 U.S. soldiers, 14 Afghan civilians, and three policemen. The Pentagon blamed the network for the attack.[92]

- 12 September 2011: US Ambassador Ryan Crocker blamed the Haqqani network for an attack on the US Embassy and nearby NATO bases in Kabul. The attack lasted 19 hours and resulted in the deaths of four police officers and four civilians. 17 civilians and six NATO soldiers were injured. Three coalition soldiers were killed. Eleven insurgent attackers were killed.[93]

- October 2011: Afghanistan's National Directorate of Security said that six people arrested in an alleged plot to assassinate President Karzai had ties to the Haqqani network.[94]

- 15 April 2012: Haqqani network fighters initiate the summer fighting season, conducting a complex attack across Kabul, Logar and Paktia provinces. Several western embassies in Kabul were attacked in the Say Wallah district.

- 1 June 2012: A massive suicide truck bomb breaches the southern perimeter wall of US Forward Operating Base Salerno in Khost province. A dozen Haqqani fighters wearing suicide vests entered the breach, but were isolated and killed by US Forces.

- 31 May 2017: a truck bomb exploded in a crowded intersection in Kabul, Afghanistan, near the German embassy,[95] killing over 150 and injuring 413,[96] mostly civilians, and damaging several buildings in the embassy.[97][98] The attack was the deadliest terror attack to take place in Kabul. Afghanistan's intelligence agency NDS claimed that the blast was planned by the Haqqani Network.[99][100]

الموقع

The Haqqani network operates in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in Northern Pakistan, near the southeastern border of Afghanistan.[101][102] The network has used the ambiguity of the FATA to cloak its activities and avoid interference. The strategy worked well until President Obama ramped up UAV strikes in the Northern Waziristan region. The organizational headquarters is supposedly in Miram Shah, where the group operates base camps to facilitate activities such as weapons acquisitions, logistical planning and military strategy formulation. Haqqani-controlled regions of northern Pakistan have also served as strategic safe-havens for other Islamic militant organizations, such as Al-Qaeda, the Pakistani Taliban (TTP), Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), and members of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU). The strategic location of the Haqqani network facilitates interaction between many of the insurgent groups.[103][104]

The Haqqani network's tribal connections in Northern Waziristan and the de facto regime that it has established with courts, law enforcement, medical care, and governance have often brought it great support from locals.[32] Its familiarity of terrain, such as mountain passes, also grants them excellent access between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In September 2011, Sirajuddin Haqqani claimed during a telephonic interview to Reuters that the Haqqani network no longer maintained sanctuaries in northwestern Pakistan and the robust presence that it once had there and instead now felt safer in Afghanistan: "Gone are the days when we were hiding in the mountains along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Now we consider ourselves more secure in Afghanistan beside the Afghan people."[77] According to Haqqani, there were "senior military and police officials" who are aligned with the group and there are even sympathetic and "sincere people in the Afghan government who are loyal to the Taliban" who support the group's aim of liberating Afghanistan "from the clutches of occupying forces."[77] In response to questions from the BBC's Pashto service, Siraj denied any links to the ISI and stated that Mullah Omar is "our leader and we totally obey him."[105]

التورط الپاكستاني المزعوم

While some Afghan and American officials accuse Pakistan of harboring the Haqqani network, Pakistan has denied any links.[106]

Abdul Rashid Waziri, a specialist at Kabul's Center for Regional Studies of Afghanistan, explains that links between the Haqqani network and Pakistan can be traced back to the mid-1970s,[9] before the 1978 Marxist revolution in Kabul. During the rule of President Daoud Khan in Afghanistan (1973–78), Jalaluddin Haqqani went into exile and based himself in and around Miranshah, Pakistan.[107] From there he began to form a rebellion against the government of Daoud Khan in 1975.[9] The network allegedly maintains ties with the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), and Pakistan's army had been reportedly reluctant to move against them in the past.[42][108]

However, recently there has been a paradigm shift within the Pakistani military and as of 2014 a massive military offensive launched in North Waziristan, named Operation Zarb-e-Azb has targeted all militants including the Haqqanni network. The operation is currently on-going and is commanded by General Qamar Javed Bajwa.[109]

The New York Times reported in September 2008 that Pakistan regards the Haqqani as an important force for protecting its interests in Afghanistan in the event of American withdrawal from there and therefore is unwilling to move against them.[108] Pakistan presumably[ممن؟] feels pressured that India, Russia, and Iran are gaining a foothold in Afghanistan. Since it lacks the financial clout of the other countries, Pakistan hopes that by being a sanctuary for the Haqqani network, it can assert some influence over its turbulent neighbor. In the words of a retired senior Pakistani official: "[We] have no money. All we have are the crazies. So the crazies it is."[110] The New York Times and Al Jazeera later reported in June 2010 that Pakistan's Army chief General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani and chief of the ISI General Ahmad Shuja Pasha were in talks with Afghan President Hamid Karzai to broker a power-sharing agreement between the Haqqani network and the Afghan government.[111][112] Reacting to this report both President Barack Obama and CIA director Leon Panetta responded with skepticism that such an effort could succeed.[113] The effort to mediate between the Haqqanis and the Afghan government was launched by Pakistan after intense pressure by the US to take military action against the group in North Waziristan.[114] Karzai later denied meeting anyone from the Haqqani network.[115] Subsequently, Kayani also denied that he took part in the talks.[116]

Anti-American groups of Gul Bahadur and Haqqani carry out their activities in Afghanistan and use North Waziristan as rear.[117] The group's links to Pakistan have been a sour point in Pakistan – United States relations. In September 2011, the Obama administration warned Pakistan that it must do more to cut ties with the Haqqani network and help eliminate its leaders, adding that "the United States will act unilaterally if Pakistan does not comply."[118] In testimony before a US Senate panel, Admiral Mike Mullen stated that the network "acts as a veritable arm of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence Agency."[119] Although some U.S. officials allege that the ISI supports and guides the Haqqanis,[119][120][121][122][123] President Barack Obama declined to endorse that position and stated that "the intelligence is not as clear as we might like in terms of what exactly that relationship is"[124] and US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said "We have no evidence of" Pakistani involvement in attacks on the US embassy in Kabul.[125]

Pakistan in return rejected the notion that it maintained ties with the Haqqani network or used it in a policy of waging a proxy war in neighboring Afghanistan. Pakistani officials deny the allegations by asserting that Pakistan had no relations with the network. In response to the allegations, Interior Minister Rehman Malik claimed that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had "trained and produced" the Haqqani network and other mujahideen during the Soviet–Afghan War.[126][127][128][129] The Pakistani interior minister also warned that any incursion on Pakistani territory by U.S. forces will not be tolerated. A Pakistani intelligence official insisted that the American allegations are part of "pressure tactics" used by the United States as a strategy "to shift the war theatre."[130] An unnamed Pakistani official was reported to have said after a meeting of the nation's top military officials that "We have already conveyed to the US that Pakistan cannot go beyond what it has already done".[131] However, Pakistani claims were contradicted by the network's warnings against any U.S. military incursions into North Waziristan.[126][128] However a month after the allegation, ties improved slightly and the US asked Pakistan to assist it in starting negotiation talks with the Taliban.[132] In 2014, the Pakistani Armed Forces launched a major offensive Operation Zarb-e-Azb in North Waziristan aimed at displacing all militants foreign and domestic, including the Haqqani network from its soil. The operation is currently ongoing.

الخصوم

الهجمات العسكرية لآيساف

In July 2008, Jalaluddin's son Omar Haqqani was killed in a firefight with coalition forces in Paktia.[133] In September 2008, Daande Darpkhel airstrike drones fired six missiles at the home of the Haqqanis and a madrasah run by the network. However both Jalaluddin and Sirajuddin were not present though several family members were killed.[85] Among 23 people killed was one of Jalaluddin's two wives, sister, sister-in-law and eight of his grandchildren.[108] In March 2009, the US State Department announced a reward of $5 million for information leading to the location, arrest, or conviction of Sirajuddin under the Rewards for Justice Program.[134] In May 2010, US senator and United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Chair Dianne Feinstein wrote to United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton urging her to add the Haqqani network to U.S. State Department list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations.[135]

ISAF and Afghan forces killed a network leader, Fazil Subhan, plus an unknown number of Haqqani militiamen, in a raid in Khost in the second week of June 2010. In a press release, ISAF reported that Subhan helped facilitate the movement of Al-Qaeda fighters into Afghanistan.[136][137]

In late July 2011, U.S. and Afghan special forces killed dozens of insurgents during an operation in eastern Paktika province to clear a training camp the Haqqani network used for foreign (Arab and Chechen) fighters; reports of the number killed varied, with one source saying "more than 50"[138] to "nearly 80".[139] Disenfranchised insurgents told security forces where the camp was located, the coalition said.[138]

On 1 October 2011, NATO announced the capture of Haji Mali Khan, "the senior Haqqani commander in Afghanistan," during an operation in Jani Khel district of Afghanistan's Paktia province. Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid denied that the capture occurred while Haqqani network members declined to respond to the announcement.[71][72]

According to an unnamed Pakistani official a US drone strike on a compound killed Jamil Haqqani, an "important Afghan commander of Haqqani network" responsible for logistics in North Waziristan, on 13 October 2011. Three other network fighters were also killed in the two missile blasts. The compound was located in Dandey Darpakhel village, about 7 km (4 miles) north of Miranshah.[140]

In mid-October 2011, Afghan and NATO forces launched "Operation Shamshir" and "Operation Knife Edge" against the Haqqani network in south-eastern Afghanistan, with the intent to counter possible security threats in the border regions. An ISAF spokesman said that Operation Shamshir "was aimed at securing key population centers and expanding the Kabul security zone,"[141] while Afghan Defense Minister, Abdul Rahim Wardak, explained that Operation Knife Edge would "help eliminate the insurgents before they struck in areas along the troubled frontier."[142] The two operations ended on 23 October 2011 and at least 20 insurgents, of the some 200 killed or captured, had ties to the Haqqani network according to ISAF.[4][141]

On 2 November 2011, The Express Tribune reported that the Pakistani Army had agreed with the United States to restrict the network's movement along the Afghan border in exchange for America dropping its demands for a full-scale offensive. The report emerged soon after a visit by Hillary Clinton to Pakistan.[143]

Curtis M. Scaparrotti, commander of International Security Assistance Force Joint Command, has said that Haqqani can be defeated through a combination of a layered defense in Afghanistan and interdiction against the sanctuaries in Pakistan.[144]

In June 2014 a drone attack reportedly killed 10 members of the Haqqani network including a high-level commander, Haji Gul, in the country's tribal area of North Waziristan. The Pakistan government publicly condemned the attack, but according to a government official had privately approved it.[145]

الهجمات العسكرية الپاكستانية

In 2014, the Pakistani Armed Forces launched a major offensive Operation Zarb-e-Azb in North Waziristan aimed at displacing all militants foreign and domestic, including the Haqqani network from its soil. On 5 November 2014, Lt. Gen. Joseph Anderson, a senior commander for US and Nato forces in Afghanistan, said in a Pentagon-hosted video briefing from Afghanistan that the Haqqani network is now "fractured" like the Taliban. "They are fractured. They are fractured like the Taliban is. That's based pretty much on the Pakistan's operations in North Waziristan this entire summer-fall," he said, acknowledging the effectiveness of Pakistan's military offensive. "That has very much disrupted their efforts in Afghanistan and has caused them to be less effective in terms of their ability to pull off an attack in Kabul," Anderson added. The operation is currently ongoing.[146]

العقوبات

Until 1 November 2011, six Haqqani network commanders were designated as terrorists under Executive Order 13224 since 2008 and their assets were frozen while prohibiting others from engaging in financial transactions with them:[74]

- In March 2008, the US State Department designated Sirajuddin Haqqani a terrorist and a year later issued a $5 million bounty for information leading to his capture.[74]

- The State Department placed Nasiruddin Haqqani on its list of terrorists in July 2010.[74]

- In February 2011, Khalil al Rahman Haqqani was designated a terrorist by the US State Department.[74]

- In an effort to stop the flow of funds to the network, the US State Department announced on 16 August 2011 measures against Sangeen Zadran as "Shadow Governor for Paktika Province, Afghanistan and a commander of the Haqqani Network." The US designated Zadran under Executive Order 13224 while the United Nations listed him under Security Council Resolution 1988.[62][63]

- The U.S. Department of Treasury added Abdul Aziz Abbasin, "a key commander in the Haqqani Network", to the list of individuals on the executive order in September 2011.[70][74]

- On 1 November 2011, Haji Mali Khan, who was already in ISAF custody, was added to the list.[74]

In September 2011, the US Senate Appropriations Committee voted to make a $1 billion counter-insurgency aid package to the Pakistani military conditional upon Pakistani action against militant groups, including the Haqqani network. The decision would still need to receive approval from the US House of Representatives and the US Senate.[147] According to the press release, "[t]he bill includes strengthened restrictions on assistance for Pakistan by conditioning all funds to the Government of Pakistan on cooperation against the Haqqani network, al Qaeda, and other terrorist organizations, with a waiver, and funding based on achieving benchmarks."[148]

On 7 September 2012, the Obama administration blacklisted the group as a foreign terrorist organization. The decision was mandated by Congress and was a source of debate within the administration.[46][149][150]

On 5 November 2012, the United Nations Security Council added the network to a blacklist of Taliban-related groups.[151]

On 9 May 2013 the government of Canada listed it as a terror group.[152]

In March 2015 the UK proscribed the Haqqani network as a terror group.[153]

محاولات التفاوض

US officials confirmed that they held preliminary talks during the summer of 2011 with representatives of the militant network at the request of the ISI. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that the US had reached out to the Haqqanis to gauge their willingness to engage in a peace process and that "Pakistani government officials helped to facilitate such a meeting."[154] The New York Times reported that talks secretly began in late August 2011 in the United Arab Emirates between a midlevel American diplomat and Ibrahim Haqqani, Jalalludin's brother. Gen. Ahmed Shuja Pasha, head of the ISI, brokered the discussion, but little resulted from the meeting.[155]

انظر أيضاً

- ضربات المسيرات في پاكستان

- Hafiz Gul Bahadur

- القوة الدولية للمساعدة الأمنية

- الحرب في شمال غرب پاكستان

- الحرب في أفغانستان (2001-الحاضر)

- Bowe Bergdahl

الهامش

- ^ "Who are the Haqqanis?". Quilliam. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "The Haqqani Network".

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Rassler, Don; Vahid Brown (14 July 2011). "The Haqqani Nexus and the Evolution of al-Qaida" (PDF). Harmony Program. Combating Terrorism Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت NATO: 200 Afghan militants killed, captured by Deb Riechmann. 24 October 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Gopal, Anand (1 June 2009). "The most deadly US foe in Afghanistan". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "Taliban announces death of Jalaluddin Haqqani | FDD's Long War Journal". 4 September 2018.

- ^ "The Haqqani Network".

- ^ Syed Salaam Shahzaddate=5 May 2004. "Through the eyes of the Taliban". Asia Times. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Questions Raised About Haqqani Network Ties with Pakistan". International Relations and Security Network. 26 September 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Coll, Steve Ghost Wars (New York:Penguin, 2004) pp. 201-202

- ^ "Rare look at Afghan National Army's Taliban fight". BBC News. 28 January 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ^ "Taliban attack NATO base in Afghanistan". Al Jazeera English. 2 December 2012. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ^ "US commander commends Zarb-e-Azb for disrupting Haqqani network's ability to target Afghanistan". The Express Tribune. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014.

- ^ "Pakistan military operation disrupted Haqqani network: US commander". Economic Times. 6 November 2014.

- ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (25 June 2021). "Taliban's deputy emir issues guidance for governance in newly seized territory". FDD's Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (7 June 2021). "U.N. report cites new intelligence on Haqqanis' close ties to al Qaeda". FDD's Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "Founder of Haqqani Network Is Long Dead Aide Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Khan, Haq Nawaz; Constable, Pamela (19 July 2017). "A much-feared Taliban offshoot returns from the dead". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Alikozai, Hasib Danish. "Afghan General: Haqqani Network, Not IS, Behind Spike in Violence". VoA News. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "What Is the Haqqani Network?" (in الإنجليزية). VOA News.

- ^ "What Is the Haqqani Network?" (in الإنجليزية). VOA.

- ^ Mashal, Mujib (2018-09-04). "Taliban Say Haqqani Founder Is Dead. His Group Is More Vital Than Ever". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ "What Is the Haqqani Network?" (in الإنجليزية). VOA News.

- ^ Abubakar Siddique (26 September 2011). "Questions Raised About Haqqani Network Ties with Pakistan". ETH Zurich Center for Security Studies. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Haqqani network to be designated a terrorist group". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Pakistan bans Haqqani network after security talks with Kerry".

- ^ Green, Matthew (13 November 2011). "'Father of Taliban' urges US concessions". Financial Times. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

The school also has a place in the hearts of the commanders of the Haqqani network, a family-run insurgent dynasty that specialises in Kabul suicide bombings. Jalaluddin Haqqani, the group's patriarch, studied at the seminary, from which he derives his name.

- ^ أ ب "Jeffrey Dressler; The Haqqani Network, A Strategic Threat." Institute for the Study of War 2010.

- ^ Coll, Steve Ghost Wars (New York:Penguin, 2004) pp. 201-202

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Gopal, Anand; Mansur Khan Mahsud; Brian Fishman (3 June 2010). "Inside the Haqqani network". Foreign Policy. The Slate Group, LLC. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت Mir, Amir (15 October 2011). "Haqqanis sidestep US terror list". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث Brown, V.; Rassler, D.; Fountainhead of Jihad: The Haqqani Network, 1973–2012. Columbia University Press 2013.

- ^ أ ب Fountainhead of Jihad

- ^ "The Battle for Tora Bora"

- ^ Bergen, Peter; "The Battle for Tora Bora." The New Republic, 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda's Great Escape"

- ^ "Smucker, Philip; Al-Qaeda's Great Escape: The military and media on Terror's" Dulles, Virginia, Bassey's 2004.

- ^ أ ب "Al Qaeda active in 12 Afghan provinces: UN". Daijiworld. Indo-Asian News Service. 26 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Herold, Marc (February 2002). "The failing campaign: A relentless American campaign seeking to kill Maulvi Jalaluddin Haqqani rains bombs on civilians as the most powerful mujahideen remains elusive". The Hindu. Vol. 19, no. 3.[dead link]

- ^ أ ب Syed Salaam Shahzaddate=5 May 2004. "Through the eyes of the Taliban". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2004. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ DeYoung, Karen (13 October 2011). "U.S. steps up drone strikes in Pakistan against Haqqani network". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Gall, Carlotta (17 June 2008). "Old-Line Taliban Commander is Face of Rising Afghan Threa". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ Partlow, Joshua (27 May 2011). "Haqqani insurgent group proves resilient foe in Afghan war". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Dressler, Jeffrey (5 September 2012). "The Haqqani Network: A Foreign Terrorist Organization" (PDF). ISW. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Wanted Sirajuddin Haqqani Up to $5 Million Reward". Rewards for Justice. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ أ ب Schmitt, Eric (6 September 2012). "U.S. Backs Blacklisting Militant Organization". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Roggio, Bill (9 September 2012). "Taliban call Haqqani Network a 'conjured entity'". Long War Journal. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Lawrence, Kendall. "The Haqqani Network". Threat Convergence Profile Series. The Fund For Peace. October 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Afghan militant leader Jalaluddin Haqqani 'has died'". BBC. 31 July 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Taliban deny reports of Haqqani network founder's death". AFP. 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "Haqqani network's founder dies after long illness, Afghan Taliban says", by Alexander Smith and Mushtaq Yusufzai, NBC News

- ^ @Zabihullah_4 (3 September 2018). "Statement of Islamic Emirate regarding passing away of prominent Jihadi figure, scholar and warrior Mawlawi Jalaluddin Haqqani (RA) justpaste.it/4z8if" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018 – via Twitter.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث Khan, Zia (22 September 2011). "Who on earth are the Haqqanis?". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Top Haqqani network militant 'killed in Pakistan'". BBC. 25 August 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Rahim Faiez; Rebecca Santana (26 August 2012). "Taliban deny report of Haqqani commander's death". The State. AP. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "Afghanistan says sources confirm militant commander Badruddin Haqqani has been killed". The Washington Post. AP. 26 August 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Karen DeYoung (29 August 2012). "U.S. confirms killing of Haqqani leader in Pakistan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Pakistani Officials Confirm Death of Key Militant". Time Magazine. AP. 30 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Bill RoggioSeptember 8, 2013 (2013-09-08). "Taliban confirm death of Badruddin Haqqani in drone strike last year". The Long War Journal. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Taliban-linked militant killed in U.S. drone strike in Pakistan". Reuters. 6 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Designation of Haqqani Network Commander Sangeen Zadran." Office of the Spokesperson. 16 August 2011. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2011/08/170582.htm. Accessed 17 July 2012.

- ^ أ ب "US tries to stem funds to Haqqani network commander". The Express Tribune. AFP. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Designation of Haqqani Network Commander Sangeen Zadran". U.S. Department of State. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Afghan Taliban offers to swap captive U.S. soldier Bowe Bergdahl for 5 Guantanamo detainees". CBS News.

- ^ Roggio, Bill (22 July 2010). "US adds Haqqani Network, Taliban leaders to list of designated terrorists". The Long War Journal. Public Multimedia Inc. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Khan, Tahir (11 November 2013). "Senior Haqqani Network leader killed near Islamabad". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ^ أ ب S.B. Shah (21 November 2013). "US drone strike kills senior Haqqani leader in Pakistan". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ "Security Council 1988 Sanctions Committee Adds Individual Abdul Rauf Zakir". United Nations. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Amir Mir (25 November 2013). "Who was Maulvi Ahmad Jan, the droned Haqqani leader?". The News International. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ أ ب "Treasury Continues Efforts Targeting Terrorist Organizations Operating in Afghanistan and Pakistan". U.S. Department of Treasury. 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Haqqani leader captured in Afghanistan". Financial Times. 1 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت "NATO: Haqqani Leader Captured in Afghanistan". NPR. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Nato 'kills senior Haqqani militant in Afghanistan'". BBC News. 30 June 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "US adds senior Haqqani Network leader to terrorist list". The Long War Journal. November 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Zucchino, David; Goldman, Adam (19 November 2019). "Two Western Hostages Are Freed in Afghanistan in Deal with Taliban". The New York Times.

- ^ Matthias Gebauer; John Goetz; Hans Hoyng; Susanne Koelbl; Marcel Rosenbach; Gregor Peter Schmitz (26 July 2010). "The Helpless Germans: War Logs Illustrate Lack of Progress in Bundeswehr Deployment". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

Sirajuddin Haqqani is also associated with the foreign jihadists. Haqqani, known as 'Siraj,' is the son of the legendary Afghan mujahedeen leader Jalaluddin Haqqani. Together with the Taliban and Hekmatyar, the Haqqani clan of warlords are among the three greatest opponents of Western forces in Afghanistan. In the digital war logs, his name appeared in 'Tier 1' on a list of targets to be killed or taken captive, which qualified him as one of the Western alliance's most wanted terrorists.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "No sanctuaries in Pakistan': Haqqani network shifts base to Afghanistan". The Express Tribune. 18 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Vahid Brown and Don Rassler, Fountainhead of Jihad: The Haqqani Nexus, 1973-2012, Oxford University Press (2013), p. 14

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Scott Shane; Alissa J. Rubin (24 September 2011). "Brutal Haqqani Crime Clan Bedevils U.S. in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Toosi, Nahal (29 December 2009). "Haqqani network challenges US-Pakistan relations". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (14 December 2009). "Rebuffing U.S., Pakistan Balks at Crackdown". The New York Times.

- ^ Dreazen, Yochi J., "The New Enemy", National Journal, 16 July 2011.

- ^ Moreau, Ron; Sami Yousafzai (14 November 2011). "Dueling Manifestos". The Daily Beast. The Newsweek. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ Kidnapped US reporter makes dramatic escape from Taliban, The Guardian, 21 June 2009

- ^ أ ب U.S. Missiles Said To Kill 20 in Pakistan Near Afghan Border, The Washington Post, 9 September 2008

- ^ Taliban Wanted $25 Million for Life of New York Times Reporter, ABC News, 22 June 2009

- ^ Pakistan urges united reaction after CIA blast, Financial Times, 3 January 2010

- ^ Rogio, Bill (24 May 2010). "Haqqani Network executed Kabul suicide attack". Public Multimedia. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Haqqani network threatens attacks on judges". Pajhwok Afghan News. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Roggio, Bill, "ISAF airstrike kills senior Haqqani Network commander involved in Kabul hotel attack", Long War Journal, 30 June 2011.

- ^ Kharsany, Safeeyah; Mujib Mashal (29 June 2011). "Manager gives account of Kabul hotel attack". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Jelinek, Pauline (Associated Press), "Haqqani group behind Afghan bombing, U.S. says", Military Times, 12 September 2011.

- ^ Rubin, Alissa J; Ray Rivera; Jack Healy (14 September 2011). "U.S. Blames Kabul Assault on Pakistan-Based Group". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Six arrested over 'Karzai death plot'". Al Jazeera. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ "Kabul bomb: Dozens killed in Afghan capital's diplomatic zone". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 31 May 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Mashal, Mujib; Abed, Fahim (31 May 2017). "Huge Bombing in Kabul Is One of Afghan War's Worst". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "RS Claims Police Stopped Truck From Entering Green Zone". Tolonews. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Ehsan Popalzai; Faith Karimi (31 May 2017). "Afghanistan explosion: 80 killed in blast near diplomatic area". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "Kabul bomb: Afghans blame Haqqani and Pakistan". Sky News.

- ^ Gul, Ayaz. "Deadly Truck Bomb Rocks Kabul". VOA (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Threat Convergence Profile Series: The Haqqani Network."

- ^ Lawrence, Kendall. "Threat Convergence Profile Series: The Haqqani Network." The Fund For Peace. June 2010. p. 3. <http://www.fundforpeace.org/global/library/ttcvr1127-threatconvergence-haqqani-11b.pdf Archived 26 يوليو 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Inside the Haqqani Network."

- ^ "Inside the Haqqani Network." Foreign Policy Group. 3 June 2010. <http:b//afpak.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2010/06/03/inside_the_haqqani_network_0

- ^ "Haqqani network denies killing Afghan envoy Rabbani". BBC. 3 October 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "What Is the Haqqani Network?".

- ^ "Haqqani Network". The Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت Perlez, Jane (9 September 2008). "U.S. attack on Taliban kills 23 in Pakistan". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "US commander commends Zarb-e-Azb for disrupting Haqqani network's ability to target Afghanistan". Express News. 6 November 2014.

- ^ "Snake country". The Economist. Islamabad. 1 October 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ Perlez, Jane; Gall, Carlotta (24 June 2010). "Pakistan Is Said to Pursue Foothold in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Karzai 'holds talks' with Haqqani". Al Jazeera English. 28 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Shane, Scott (27 June 2010). "Pakistan's Plan on Afghan Peace Leaves U.S. Wary". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Syed, Baqir Sajjad (16 June 2010). "Pakistan trying to broker Afghan deal". Dawn. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Kabul dismisses report Karzai met militant leader". Agence France-Presse. 29 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Kayani says he did not broker Karzai's talks with Haqqani". Dawn. 2 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Militant Networks in North Waziristan". OutlookAfghanistan.net. 26 May 2011. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen (21 September 2011). "U.S. sharpens warning to Pakistan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Pakistan 'backed Haqqani attack on Kabul' – Mike Mullen". BBC. 22 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "Pakistan condemns US comments about spy agency". Associated Press. 23 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Clinton Presses Pakistan to Help Fight Haqqani Insurgent Group". Fox News. 18 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ "U.S. blames Pakistan agency in Kabul attack". Reuters. 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "U.S. links Pakistan to group it blames for Kabul attack". Reuters. 17 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ "Obama won't back Mullen's claim on Pakistan". NDTV. 1 October 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Clinton demands action in ‘days and weeks’

- ^ أ ب "Defiant Pak refuses to go after Haqqanis". The Times of India. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "CIA created Haqqani network: Rehman Malik". Dawn. 25 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Haqqani network created by the CIA: Rehman Malik". The Tribune. 25 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "CIA, not Pakistan, created Haqqani network: Malik". The News. 26 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Brittle relations: Islamabad 'vehemently' rejects US 'proxy war' claims". The Express Tribune. 22 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Zirulnick, Ariel. "Pakistan refuses to battle Haqqani network." The Christian Science Monitor, 26 September 2011.

- ^ "US seeks Pak aid in peace efffort". The News International, Pakistan. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Haqqani’s son killed in Paktia, The News International, 11 July 2008

- ^ "Rewards For Justice: Sirajuddin Haqqani". U.S. State Department. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "US Senator: Label Pakistan Taliban, Haqqani, as terrorists". Agence France-Presse. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 17 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Roggio, Bill (14 June 2010). "US, Afghan Forces Kill Haqqani Network Commander During Raid in Khost". Long War Journal.

- ^ "Afghan, International Force Clears Haqqani Stronghold". ISAF. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ أ ب Nichols, Michelle (22 July 2011). "NATO kills 50 fighters, clears Afghan training camp". Reuters. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Rare glimpse into U.S. special operations forces in Afghanistan". Security Clearance (blog). CNN. 26 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

U.S. and Afghan troops attacked an insurgent encampment, killing nearly 80 foreign fighters…. The camp they attacked and the fighters there were part of the so-called Haqqanni network, which is responsible for many recent attacks in Afghanistan and is closely tied to al Qaeda. The Haqqanis traditionally rely on Afghan and Pakistani fighters, but in this instance most of the fighters there who were killed were Arabs and Chechens, brought into Afghanistan from Pakistan.

- ^ "US drones strike in North, South Waziristan". The Express Tribune. The Express Tribune News Network. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ أ ب Mashal, Mujib (25 October 2011). "Afghan forces target Haqqani strongholds". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "Push launched against Haqqanis in border areas". pajhwok.com. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Yousaf, Kamran (2 November 2011). "Pakistan looks to restrict Haqqanis' movement". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Tyrone C. Jr. "Objectives Achievable Despite Pakistan Sanctuaries, General Says." American Forces Press Service, 27 October 2011.

- ^ "Controversial US drone attack in Pakistan, 16 killed". Pakistan News.Net. Archived from the original on 15 June 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Operation Zarb-i-Azb disrupted Haqqani network: US general". Dawn. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "US senators link Pakistan aid to Haqqani crackdown". BBC. 22 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "Summary: FY12 State, Foreign Operations Appropriations Bill". U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "US designates Haqqani group as 'terrorists'". Al Jazeera. 7 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen (7 September 2012). "Haqqani network to be designated a terrorist group". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "UN adds Haqqani network to Taliban sanctions list". BBC News. 5 November 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "About the listing process". Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ PROSCRIBED TERRORIST ORGANISATIONS UK Home Office.

- ^ "Hillary Clinton: US held meeting with Haqqani network". BBC News. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric; David E. Sanger (30 October 2011). "U.S. Seeks Aid From Pakistan in Peace Effort". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

للاستزادة

- Vahid Brown, Don Rassler (1 February 2013). Fountainhead of Jihad: The Haqqani Nexus, 1973–2012 (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-19-932798-0.

وصلات خارجية

- Haqqani Network, GlobalSecurity.org

- Haqqani Network, Institute for the Study of War

- Sirajuddin Haqqani, Rewards for Justice Program

- Haqqanis: Growth of a militant network, BBC News, 14 September 2011

- Q&A: Who are the Haqqanis?, Reuters

- أخبار مُجمّعة وتعليقات عن شبكة حقاني في موقع صحيفة نيويورك تايمز.

- Haqqani Network Financing: The Evolution of an Industry – The Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, July 2012

- The Haqqani History: Bin Ladin's Advocate inside the Taliban – National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book, 11 September 2012

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Articles with dead external links from October 2011

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from October 2011

- العلاقات الأفغانية الپاكستانية

- Anti-Soviet factions in the Soviet–Afghan War

- Organizations designated as terrorist in Asia

- الجماعات الجهادية في أفغانستان

- الجماعات الجهادية في پاكستان

- العلاقات الأمريكية الپاكستانية

- التاريخ الحديث لأفغانستان

- Organizations designated as terrorist by the United States

- طالبان

- الحرب في أفغانستان (2001-الحاضر)

- وزيرستان

- Organisations designated as terrorist by the United Kingdom

- Organizations designated as terrorist by Canada