بطليوس

بطليوس | |

|---|---|

Location of Badajoz | |

| الإحداثيات: 38°52′49″N 6°58′31″W / 38.88028°N 6.97528°W | |

| البلد | |

| Autonomous Community | إكستريمادورا |

| الإقليم | بدخوث |

| كوماركا | تييرا ده بدخوث |

| تأسست | ح. 875 |

| أسسها | Ibn Marwan (over a previous Visigothic settlement) |

| الحكومة | |

| • Mayor | Ignacio Gragera (PP) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 1٬470 كم² (570 ميل²) |

| المنسوب (AMSL) | 185 m (607 ft) |

| التعداد ()[1] | |

| • الترتيب | 302 |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+2 (CEST (GMT +2)) |

| Postal code | 70862 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +34 (Spain) + 924 (Badajoz) |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

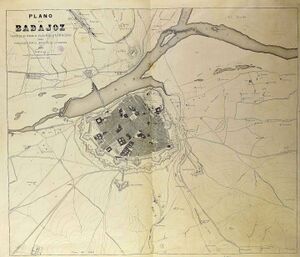

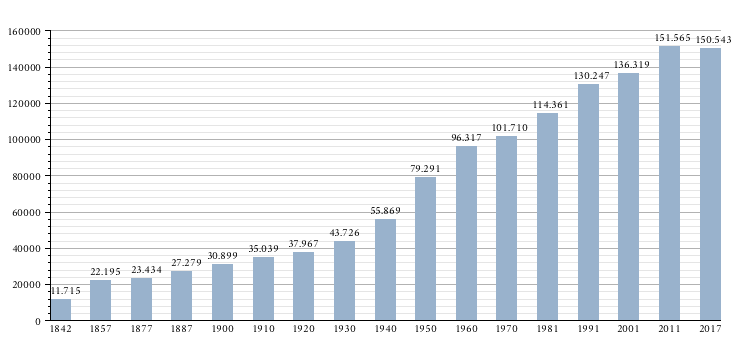

بَطَلْيُوس (بالإسبانية: Badajoz وتنطق "بدخوث") مدينة تقع في منطقة إكستريمادورا في غرب إسبانيا على مقربة من الحدود مع البرتغال. في 2011، بلغ عدد سكانها 151,565 نسمة. كانت تسمى إبان فترة الحكم الإسلامي للأندلس بطليوس نسبة لبني الأفطس.

Originally a settlement by groups such as the Romans and the Visigoths, its previous name was Civitas Pacensis. Badajoz was conquered by the Moors in the 8th century and re-founded as Baṭalyaws, and later in the 11th century the city became the seat of a separate Moorish kingdom, the Taifa of Badajoz. After the Reconquista, the area was disputed between Spain and Portugal for several centuries with alternating control resulting in several wars including the Spanish War of Succession (1705), the Peninsular War (1808–1811), the Storming of Badajoz (1812), and the Spanish Civil War (1936). Spanish history is largely reflected in the town.

Badajoz is the see of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mérida-Badajoz. Prior to the merger of the Diocese of Mérida and the Diocese of Badajoz, Badajoz was the see of the Diocese of Badajoz from the bishopric's inception in 1255. The city has a degree of eminence, crowned as it is by the ruins of the Moorish castle Alcazaba of Badajoz and overlooking the Guadiana river, which flows between the castle-hill and the powerfully armed fort of San Cristobal. The architecture of Badajoz is indicative of its tempestuous history; even the Badajoz Cathedral, built in 1238, resembles a fortress, with its massive walls. It is served by Badajoz Railway Station and Badajoz Airport.

التاريخ

العصور القديمة

Archaeological finds unearthed in the Badajoz area have been dated to the Bronze Age. Megalithic tombs are dated as far back as 4000 BC,[2] while many of the steles found are from the Late Bronze Age.[3] Other finds include weapons such as axes and swords, everyday items of pottery and utensils, and various items of jewellery such as bracelets. Archaeological excavations have revealed remnants from the Lower Paleolithic period. Artifacts have also been found at the Roman town of Colonia Civitas Pacensis in the Badajoz area, although a significant number of larger artifacts were found in Mérida.[4][5]

With the invasion of the Romans, which started in 218 BC during the Second Punic War, Badajoz and Extremadura became part of the administrative district called Hispania Ulterior (Farther Spain), which was later divided by Emperor Augustus into Hispania Ulterior Baetica and Hispania Ulterior Lusitania; Badajoz became part of Lusitania.[6] Though the settlement is not mentioned in Roman history, Roman villas such as the La Cocosa Villa have been discovered in the area, while Visigothic constructions have also been found in the vicinity.[7]

التأسيس بالعصور الوسطى

أنشأ هذه المدينة الثائر على إمارة بني أمية بقرطبة عبد الرحمن بن مروان المعروف بالجليقي، وذلك بعد مسالمته للأمير محمد بن عبد الرحمن في سنة 262 (876)، وكانت في أول أمرها تابعة لمدينة ماردة Mérida قاعدة غرب الأندلس، ثم أخذت في النمو والاتساع حتى أصبحت في عصر ملوك الطوائف حاضرة لواحدة من أكبر الممالك وهي دولة بني الأفطس. و هي الآن عاصمة لإحدى محافظتي الإقليم الذي يدعى إكستريمادورا Extremadura أي الطرف الأقصى، وتقع في أقصى غربي أسبانيا على حدودها مع البرتغال. ومن أهم معالمها الإسلامية قصبة بطليوس التي تم بناؤها في عهد الموحدون في القرن الثاني عشر.

بطليوس هي مدينة إسلامية، أنشأها أحد المولدين من معتنقي الدين الحنيف، والمنتمي إلى عائلة أهلية شهيرة: عبد الرحمن بن مروان الجليقي، وأطلق عليها اسم بطليوس، وذلك في عام 875 إبان حكم الأمير محمد الأول، وصارت أهم مركز سياسي وعسكري، اقتصادي وثقافي في غرب شبه الجزيرة. عاشت بطليوس ما بين عامي 1022 و 1094 أوج أهميتها السياسية كعاصمة لدولة بني الأفطس البرابرة، المتحدرين من سلالة مكناسة، وأسياد منطقة شاسعة ضمت: ميريدا، لشبونة، شنترين وكوينبرا، وذلك في ظل الأمير المظفر بن الأفطس، الجندي الباسل، العالم، وعاشق الشعر.

كانت المدينة شاهداً في عام 1086 على معركة الزلاقة، وسقطت نهائياً بأيدي المسيحيين في عام 1230، عندما ضم الموحدون بطليوس إلى إمبراطوريتهم، كانت الحدود الشمالية الغربية للأندلس، تشهد حدّة الصراع بين الإسلام وبين ممالك قشتالة وليون والبرتغال، التي كانت تسعى للاستيلاء على أراضي التاخو.

وإلى جانب أهميتها السياسية، عرفت بطليوس في القرنين الحادي عشر والثاني عشر أهمية ثقافية، واستقطبت النشاط الثقافي لشمال شرق الأندلس، واعتبرت في عهد بني الأفطس كأحد أهم مراكز الثقافة الرئيسة في شبه الجزيرة، وكنموذج بلاطي لإسبانيا القرن الحادي عشر: حمى الملكين المظفر والمتوكل الشعراء، ولائحة الأسماء لأدباء محليين ووافدين لائحة طويلة، فالملك المظفر كان مولعاً بالشعر، وتنسب إليه أعمال عدة، وأبرز شعراء المظفر والمتوكل ابن باج، والشاعر الداني ابن لبانة، والبرتغالي ابن مقانة.

وقد عاش ابن عبدون في كنف المتوكل، وصار بالتالي وزيراً في دولة المرابطين في عهد يوسف بن تاشفين، وابنه علي، الذي شاء أن يحيط نفسه بأبرز رجالات الغرب الشعراء، مثل أبي أيوب سليمان البطليوسي، الشاعر الطبيب أبو الأصبح، وابن سارة الشنتريني.

ومن الفلاسفة المهمين في تلك الحقبة، الفيلسوف والفقيه الباجي المولود في بطليوس عام 1013، والذي درس في قرطبة، وسافر إلى الشرق، حيث ظل ثلاثة عشر عاماً. وألف بعد عودته أعمالاً كثيرة في الشريعة، ومات في الميرية عام 1081.

وهنا، لابد من ذكر الفيلسوف البطليوسي بن السيد، بالرغم من أن حياته لم ترتبط بالمدينة التي وُلد فيها عام 1052، وقد تنقل في ممالك الطوائف، ورحل من بطليوس إلى ولاية البراثين، وقصد بالتالي طليطلة وسرقسطة، ثم استقر في بالنيا حيث توفي عام 1027، وتفسر أعماله ولادة الأنظمة الفلسفية لابن رشد وابن باجة، وأثره «كتاب الحدائق» هو أول محاولة للتوفيق بين الفقه الإسلامي والفكر اليوناني.

اجتياح بدخوث، 1812

مقالة مفصلة: حصار بدخوث (1812)

مقالة مفصلة: حصار بدخوث (1812)

In 1812, Arthur Wellesley, Earl of Wellington (and future duke), again attempted to take Badajoz, which had a French garrison of about 5,000 men.[8] Siege operations commenced on 16 March; by early April, there were three practicable breaches [أ] in the walls. These were assaulted by two British divisions on 6 April, reputed to be "Wellington's bloodiest siege", with a loss of some 5,000 British soldiers out of 15,000.[10] After a five-hour onslaught the storming of the breaches failed.[11] The French also lost some 1,200 of their 5,000 soldiers in the battle.[10] Despite the failure at the breaches, the castle and another section of undamaged wall had been attacked and the town was successfully taken by the British. After the capture of the city, the victorious troops (after getting drunk on stocks of captured alcohol) sacked the city, killing and raping numerous civilians. In the view of British historian Ronald Fraser, this was the worst night of the Peninsular War.[9] It took three days before the men were brought back into order. When order was restored some 200–300 civilians had likely been killed or injured.[12] Wellington wrote to Lord Liverpool, "The capture of Badajos affords as strong an instance of the gallantry of our troops as has ever been displayed, but I anxiously hope that I shall never again be the instrument of putting them to such a test as that to which they were put last night."[13]

Pedro Caro, 3rd Marquis of la Romana, died at Badajoz on 23 January 1811 in a fit of apoplexy, seized at the moment when he was leaving his house to concert a plan of military operations with Lord Wellington. In the Siege of Badajoz, a detachment of the 45th Regiment of Foot (later amalgamated with the 95th to form the Sherwood Foresters Regiment) succeeded in getting into the castle first and the red coatee of Lt. James MacPherson of the 45th regiment was hoisted in place of the French flag to indicate the fall of the castle. This feat is commemorated on 6 April each year, when red jackets are flown on regimental flag staffs and at Nottingham Castle. Volume 23 of the Museum of Foreign Literature, Science and Art, published in 1833, described Badajoz as "one of the richest and most beautiful towns in the south of Spain, whose inhabitants had witnessed its siege in silent terror for one and twenty days, and who had been shocked by the frightful massacre."[14] On 5 August 1883 there was an attempted mutiny by elements of the Spanish Armed Forces when a climate of confusion and chaos prevailed.[15]

الحرب الأهلية الإسبانية

The Spanish Civil War in Badajoz in the 1930s was a gruesome affair.[16] During the war, Badajoz was taken by the Nationalists in the Battle of Badajoz. Infamously, several thousand of the town's inhabitants, both men and women, were taken to the town's bullring after the battle and after machine guns were set up on the barriers around the ring, an indiscriminate slaughter began. On 14 August 1936, hundreds of Republicans were shot at the Plaza de Toros.[17] In the course of the night, another 1,200 were brought in. Overall it is estimated that over 4,000 people were murdered by the Nationalists after the battle.[18] Even those who tried to cross the Portuguese border were captured and sent back to Badajoz.[16] The troops who committed the killings at Badajoz were under the command of general Juan Yagüe, who, after the civil war, was appointed Minister of Aviation by Franco. For the actions of his troops at Badajoz, Yagüe was popularly known as the "Butcher of Badajoz".[19]

التاريخ المعاصر

After the war, the town continued to grow, although since 1960 it has suffered significant migrations to other Spanish regions and other European countries. During the following decades, the predominant economic activity of the city increasingly fell within the tertiary sector, and today Badajoz is a major commercial centre in southwestern Spain and an important bridge between Spain and Portugal for trade and cultural relations. On 6 November 1997, a heavy flood devastated several neighbourhoods of the city, causing the deaths of 21 people and devastating the property of hundreds.[20] The catastrophe was caused by the Atlantic extratropical trough crossing the Iberian Peninsula and inundating the Rivilla and Calamon brooks, which are usually dry.[20] The neighbourhood of Cerro de Reyes, near the confluence of both streams, received the brunt of the damage caused by the flood.[20]

الجغرافيا

Badajoz is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula on the bank of the Guadiana River on the border with Portugal.[21] It is the capital city of the province of the same name.[5] It is 61 كيلومتر (38 mi) from Mérida, 89 كيلومتر (55 mi) from Cáceres, 217 كيلومتر (135 mi) from Seville, 227 كيلومتر (141 mi) east of Lisbon, and 406 كيلومتر (252 mi) from Madrid. The newer part of the city is on the left bank of the river, with several industrial estates and the university hospital.

In geological terms, Badajoz is located in the South Submeseta.[22] It was founded on the banks of the Guadiana River on a Paleozoic limestone hill, carved by the river. On this hill is the Alcazaba, one of the main sights of the city. The municipality of Badajoz contains soils derived from tertiary deposits, dating to the Paleozoic era. Its average altitude is 184 متر (604 ft) above sea level. The highest points are located in the Cerro del Viento (219 متر (719 ft)), at Fuerte San Cristóbal (218 متر (715 ft)) and Cerro de la Muela (205 متر (673 ft)). The lowest point is the Guadiana River (168 متر (551 ft)).

الطقس

| متوسطات الطقس لبطليوس/بدخوث | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة |

| متوسط العظمى °ف (°م) | 55 (13) | 58 (14) | 63 (17) | 69 (21) | 76 (24) | 86 (30) | 92 (33) | 93 (34) | 84 (29) | 74 (23) | 62 (17) | 56 (13) | 72 (22) |

| متوسط الصغرى °ف (°م) | 39 (4) | 40 (4) | 45 (7) | 48 (9) | 53 (12) | 60 (16) | 63 (17) | 64 (18) | 61 (16) | 54 (12) | 45 (7) | 40 (4) | 51 (11) |

| هطول الأمطار بوصة (mm) | 2 (50.8) | 2 (50.8) | 2.4 (61) | 1.6 (40.6) | 1.1 (27.9) | 1 (25.4) | 0.1 (2.5) | 0.2 (5.1) | 1 (25.4) | 1.8 (45.7) | 2.3 (58.4) | 1.9 (48.3) | 17٫4 (442) |

| المصدر: {{{source}}} {{{accessdate}}} | |||||||||||||

السكان

In 2010, Badajoz had 150,376 inhabitants. According to the 2010 census, Badajoz had 73,074 men and 77,312 women, representing a percentage of 48.6% and a 51.4% respectively.[23] Compared to the statistics for the Extremadura region (49.7% and 50.3%), Badajoz city had a greater relative presence of women.

Although the city is the most populated of Extremadura, it has a relatively low population density (102.30 inhabitants/km2), due to the extension of its municipality, one of the largest in Spain, with an area of 1,470 km2. In addition to the metropolitan centre the population includes districts, neighborhoods and towns with small populations, the most populous of which is Guadiana, which had 2,524 people in 2012, but gained independence on 17 February 2012.[24]

- Source: INE

Note: The increase shown in 2001 was reduced because of the independence of the municipalities of Valdelacalzada and Pueblonuevo del Guadiana in 1993.[25]

الإدارة

Badajoz was the birthplace of the statesman Manuel de Godoy, the duke of Alcudia (1767–1851). Many of the provincial administration buildings are located in Badajoz, as well as the government buildings of the municipal administration. Politically, Badajoz belongs to the Spanish Congress Electoral District of Badajoz, which is the largest electoral district about of 52 districts in the Spanish Congress of Deputies in terms of geographical area and includes a significant part of the Extremadura region. The electoral district was first contested in modern times in the 1977 General Election.[26] At the time of the 2011 election, Badajoz had six deputies representing the district in congress, four from the People's Party-United Extremadura party (PP-EU), and two from the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).[27]

الأحياء

|

|

|

|

Districts

| Name | Type | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Alcazaba | District | 254 |

| Alvarado | District | 389 |

| Balboa | District | 532 |

| Gévora | District | 2308 |

| Guadiana del Caudillo | Gained independence on 17 February 2012[28] | 2543 |

| Novelda del Guadiana | District | 909 |

| Sagrajas | District | 631 |

| Valdebótoa | District | 1.294 |

| Villafranco del Guadiana | District | 1.544 |

| TOTAL PEDANÍAS | 7861 |

الاقتصاد

Historically, frequent wars ravaged Badajoz's economy and people were poor. Agricultural land was not fertile with no industry of any major importance in its territory. However, the historic monuments in the town and also in Mérida were major attractions to visitors, leading to the growth of tourism, and in recent years there has been some industrial development.[16]

Badajoz primarily is now a commercial city, ranked 25th place in economic importance in Spain according to Spain's Economic Yearbook for 2007, published by Servicio de Estudios de La Caixa. Because of its location, the city shares a considerable transit trade with Portugal. The service sector is dominant in the city. The main shopping street is Menacho, where most national and international chains are located. The Centro Comercial Abierto Menacho is the largest outdoor shopping centre in Extremadura which has had several hundred thousand euros invested into it, and it is visited by thousands of Portuguese a year.[29] Notable industries include manufacturing of linen, woollen and leather goods, hats, pottery, and soap.[30] Trade thrives on customers from the province and Portugal. Because of the importance of such trading relations with the neighboring country, in 2006, a new trade fair venue, Institución Ferial de Badajoz (IFEBA) was established in the suburbs near the bank of the Caia River. An economic and cultural centre, it has a wide range of markets from fish and various food stalls to health shops,"[31] The Old Town area has been affected by this trade fair but is slowly recovering, with the opening of new stores.[32]

The city's industrial land on the western side of the river is concentrated almost entirely in a large industrial estate, El Nevero, located next to the A-5 (one of the six radial roads in Spain with numbers A-1-A-6), which is continually expanding, with a diversity of companies operating there. There are also other industrial estates in the suburbs and small businesses in neighborhoods like San Roque. In summer 2007, the project to build the new 38 million euro headquarters of the Caja de Badajoz was made public,[33] which began to be built in October 2008 and is currently in use. The Torre Caja Badajoz is a financial centre that has a building height of 88 متر (289 ft) with 17 floors, now the tallest building in Extremadura.[34] The city also has an airport, located 14 كيلومتر (8.7 mi) from the town centre, expanded in 2009 and a conference centre.[35]

المعالم

The city is studded with Moorish and medieval architecture, although its remnants of Roman and Visigothic architecture are not as prominent as in nearby Mérida.[5] The Alcazaba fortress is the most notable structure in the city which attests to the Moorish culture in Badajoz. It was the only important fort on the southern Portuguese frontier during the 17th and 18th centuries and controlled the routes of southern Portugal and Andalusia and was a staging point for invasions against Portugal.[36] It was occupied by the dukes of La Roca during the Christian period. It presently serves as the Archeological Museum of Badajoz.[37] Many of Badajoz's historical monuments which were in ruins have been refurbished. Its restaurants, pubs and nightlife are a major attraction for the Portuguese across the border.[38] The 13th-century Badajoz Cathedral (converted from a mosque in 1238) is in the old city and its architecture is indicative of the tempestuous history of Badajoz, resembling a fortress, with its massive walls.[39] Three of the cathedral's windows are unique – one is in Gothic style, the second is Renaissance style and the third is in Platersque style. [40]

مباني البلدية

Palacio de Congresos de Badajoz, the congressional palace, is the work of the architects José Selgas and Lucia Cano. Palacio Municipal houses the City Hall. The remains of the original City Hall building are in ruins. The current building dates to 1852, and the clock was added in 1889.[41] In 1937, the municipal architect, Rodolfo Martinez, renovated the building, with particular emphasis on stylistic uniformity, expanding its towers and changing its decorative elements. It features a balustrade, a central balcony and columns.

Badajoz has several municipal libraries serving the city and wider province, including the Biblioteca Pública Municipal A. Dominguez, Biblioteca Pública Municipal Bda. de Llera, Biblioteca Pública Municipal Cerro de Reyes, Biblioteca Pública Municipal Pardaleras, and the Biblioteca Pública Municipal San Roque.

المواقع التاريخية

القصبة

The Alcazaba, a Moorish citadel built in the 9th century by Ibn Marwan, was fortified by the Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf in 1169, although there are traces of earlier work dating back to 913 and 1030. The Alcazaba served as the primary residences for the rulers of the Taifa of Badajoz in the 11th and 12th centuries. The Almohad rulers were expelled in the 13th century at the hands of Alfonso IX of León.[42] The Torre de Espantaperros has a height of 30 متر (98 ft) and is built of mud and mortar. It has an octagonal plan with a quadrangular structure that once provided scenic views of the countryside. The name is attributed to the sharp ringing of a bell that was one installed in the tower. The building attached to it, built in the 16th century called La Galera, once served as city hall, then a prison and finally it is now the Archaeological Museum. A well-tended garden surrounded this monument where archeological finds from the Visigothic, Roman, and other periods were found.[43][16][44]

Vauban fort

The Vauban military fort was built in the 17th century during the war between Spain and Portugal that lasted from 1640 to 1668 as a defense measure to counter-attack forces entering the city from the northwest and southeast. It is made of stone, brick and lime concrete. It has eight bastions built on the northern part of the fort as the Guadiana and Rivilla rivers on the south provided the defense. The bastions are named as the San Pedro, La Trinidad, the Santa María, the San Roque, the San Juan, the Santiago, the San José and the San Vicente.[45]

La Giralda

La Giralda, located near Plaza de la Soledad, is a replica of the Giralda in Sevilla. The structure was completed in 1930 by a local businessman for commercial intent.[46] Built in the neo-Arab Andalusian regionalist style, it is decorated with ceramic tiles and metal work and has the symbol of Mercury embossed on it as symbol of commerce.[47] In 1978, Telefónica acquired the building and refurbished it, established operating offices. In 1998, Telefónica vacated the structure, and four years later, offered the structure to potential buyers for €4.2 million. No buyer was uncovered, and Telefónica announced plans to reestablish local offices in the Giralda but later abandoned it. Various proposals for the local government to acquire the building have been made, including plans for appropriating an expansion of the Museum of Fine Arts, a regional cultural centre, and an Easter-centric museum, Easter being a major touristic draw for the city.[48]

Puerta de Palmas

The Puerta de Palmas was built in 1551.[49] It has two cylindrical towers flanking the entrance door. Prince Philip II and Emperor Charles V and date of construction are mentioned on the outer side of the tower. The towers are fortified with battlements and they have two decorative cords at the top and bottom levels. Its entrance is east-facing, and is double-arched and is decorated with medallions of the shield of the Emperor Charles V. It was once used as a prison, but has since undergone many renovations and has been an entrance point to the city.[49]

Real Monasterio de Santa Ana

It is a Christian monastery in Badajoz, declared a Bien de Interés Cultural site in 1988.[50] It is the headquarters of the Order of St. Clare in the city and lies in the heart of the old city. It was founded in 1518 by Ms. Leonor de Vega i Figueroa, under the blessing of Pope Leo X, and belonged to the jurisdiction of the Franciscan province of San Miguel.[50] According to the tombstone in the grounds, Figueroa was abbess of the monastery for forty years until her death on April 17, 1558. She was buried in the grounds, until moved to the Cripta Real del Monasterio de El Escorial. The monastery underwent a major transformation in the 18th century although the original structure partly remains.[50] Outwardly, part of the building has buttresses and a tower with two bells. On the vault of the chancel stands a lookout tower with a lattice brick convent, topped with pinnacles. The church of the monastery has a single nave which was rebuilt in the late 17th century, and the presbytery is covered by a late Gothic rib vault dated to the first half of the 16th century.[50] The church contains numerous altarpieces, imagery, paintings, and silverware.[50]

الحدائق

The Jardines de la Galera date back to the 10th century from the aftasids. They are nestled between the Torre de Espantaperros and the Chemin de ronde, within the Alcazaba. Many Alhambran ruins still exist within the gardens, and have been open to the public since 2007 after the site was restored after being closed for more than thirty years. The etymology of the gardens stems from the fact that the gardens provided a respite for prisoners sentenced to the gallows in Seville. Plant species extant in the gardens include cinnamomum camphora, dichondra repens, ceiba speciosa, and trees of the myrtle, laurel, orange, lemon, and pomegranate.[51] Other parks and gardens include Castelar, which has a central pond and several monuments dedicated to the romanticist writer Carolina Coronado and to Luis Chamizo Trigueros,[52] la Legión, Rivillas y Calamón, San Fernando, and La Viña.The city also has a water and leisure park, called the Lusiberia.[35]

المتاحف

The Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo (MEIAC) has collections of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American artists. The building is located on the site of the old Pretrial Detention and Correctional centre, which had been built in the mid-1950s on the grounds of a former 17th-century military stronghold, known as the Fort of Pardaleras.[53][54] The Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes (Provincial Museum of Fine Arts), the premier gallery of Extremadura, is set in two palatial 19th-century homes next to the Plaza de la Soledad. It is 2،000 متر مربع (22،000 sq ft) in size, with more than 1,200 paintings and sculptures from the 16th to the 20th century representing over 350 artists such as Zurbarán, Luis de Morales, Caravaggio, [55] Flemish painters, Francisco de Goya, Felipe Checa, Torre Isunza, Eugenio Hermoso, Adelard Covarsí, Antonio Juez Nieto, Francisco Pedraja Muñoz, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dalí, among others.

The Museo de la Ciudad "Luis de Morales" ("Luis de Morales" City Museum) was built in what may have been the home of the Renaissance painter Luis de Morales and contains many his paintings.[16] The Museo Arqueológico Provincial (Provincial Archaeological Museum) is located within the fortress, containing pieces from all parts of the Province of Badajoz. The building houses the 16th-century palace of the dukes of Feria. The collection is organized into six major areas: prehistory, early history, Roman, Visigoth, Medieval Islam and Christian. The elegant building is built of stone and brick masonry, and has four towers at the corners with a terraced facade. The interior is made up of Mudejar brick arches resting on octagonal columns.[56]

The Museo Catedralicio (Cathedral Museum) is situated on the cathedral grounds. It provides a historical journey through the different stages of the building's construction. It also features artifacts from the founding of the archdiocese to the present day. The collections include Filipino ivories, carvings and Flemish tapestries, the tombstone of Alfonso Suárez de Figueroa, and the Custodia Procesional del Corpus of 1558. There are also works by Luis de Morales and Zurbarán.[57] The Museo Taurino (Bullfighting Museum) is located in the city centre, organized by the Extremadurian Bullfighting Club. It includes posters, photographs and objects from the world of bullfighting.[58] The Museo del Carnaval (Carnival Museum) opened in 2007 in the Menacho centre. Costumes of groups who participated over the years in the city's carnival are exhibited in the museum. In 2008, it joined the Extremadura network of museums.[59]

الميادين

Plaza de España is in the centre of the city, the layout was designed by the city architect Rodolfo Martinez in 1917 and completed in 1920.[60] The large cathedral centers the historical area. Plaza de Cervantes is considered place of importance for the history of Badajoz. Parts of the square occupy an area which belonged to St. Andrew's Church and its cemetery. It is decorated in white marble with a concentric mosaic of pointed stars dating to 1888. Plaza Alta, recently restored, was for centuries the center of the city since it exceeded the limits of the Muslim citadel; it was formerly known simply as "the square". Spanish flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucía performed on the Plaza Alta on 10 July 2013.[61] La Giralda is located near Plaza de la Soledad.

المباني السكنية

Casa Álvarez-Buiza, a private house and commercial complex, was built in the San Juan district by Adel Franco Pinna between 1918 and 1912.[62] The building located on the Plaza de La Soledad once housed the offices of the Bank of Spain.[63] Artistic elements include the use of lime, brick and colorful ceramics with an Andalusian influence. Casa del Cordón is a private house, built in the late Gothic style of the early 16th century, and has mullioned windows. It currently houses the Archdiocese. Casa Puebla, built in 1921, is one of the other designs of Pinna, who designed numerous buildings around Badajoz. It is one of the best examples of regional architecture in Andalusian style and the property has two facades, the main one featuring neo-Renaissance elements.[64]

المقابر

During the Visigoths period the burials, as noted from the archeological finds, were near the Picuriña, Pardaleras, and Cerro de Reyes sites. During the Arab period, burials were along the roads and near the eastern suburb of the Citadel, close to Cerro de la Muela and also in the area of Santiago bastion; these locations were noted during recent excavations. Badajocenses Christians from the earliest centuries towards the end of 19th century buried their dead in or near churches.[65]

Badajoz's oldest two cemeteries are Cementerio de San Juan and Cementerio de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad. The cemeteries in active use are the Cementerio de San Juan, Cementerio Virgen de las Nieves de Balboa, Cementerio de la Inmaculada Concepción de Gévora, Cementerio San Isidro de Novelda, Cementerio Inmaculado Corazón de María de Valdebótoa and Cementerio Santiago Apóstol de Villafranco.[66] The Cementerio de San Juan is the oldest of cemeteries still in service and is dated to earlier than1839.[67][68]

الجسور

The city of Badajoz is home to five bridges, four of which span the Guadiana.[69][70]

The Puente de Palmas, also known as Puente Viejo, is the oldest bridge in Badajoz; the masonry was first laid in 1460, but a sudden rise in the river's waters destroyed the structure in 1545.[71] It was rebuilt under D. Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, Governor of Badajoz, during the reign of Philip II of Spain. In 1603, 16 of its 24 spans were destroyed by floods and were restored between 1609 and 1612. The bridge was once again rebuilt in 1833; José María Otero was the engineer and Valentin Falcato, the architect.[71] Further improvements were made during the early 21st century, when the number of spans was increased to 32 and towers were added at both ends giving a total length of 600 متر (2،000 ft).[71] The bridge reflects the city's history with all the changes made to its spans, arches, pillars and buttresses over the centuries.

Puente de la Universidad, or Puente Nuevo, is downstream of the old Palmas Bridge. It was built in 1960.[72] Puente de la Autonomía Extremeña was completed in 1990 and is located upstream of Puente de Palmas, connecting to the major roads which lead to Madrid and to Highway N-435 Badajoz-Fregenal de la Sierra.[73] Puente Real is a suspension bridge across the Guadiana, the fourth bridge in the city which was completed in 1994 The foundation stone was laid by the King of Spain in 1992. It has six spans of viaducts of 32 متر (105 ft) each in a total bridge length of 452 متر (1،483 ft). It has a bicycle lane and links to the Elvas Avenue leading to Portugal and many other city centres.[74]

الثقافة والتعليم

While not a city renowned for its culture and art, many notable artists, musicians, and writers were born in the city. Hailing from the city in the arts are the actors Luis Alcoriza, Manuel de Blas, the writers Arturo Barea, Vicente Barrantes Moreno, José López Prudencio, Emilio Morote Esquivel, Jesús García Calderón, the singers Antonio Hormigo, Rosa Morena, Federico Cabo, Guadiana Almena, La Caita, Porrina de Badajoz and the pianists Cristóbal Oudrid and Esteban Sánchez, and painters such as Luis de Morales, Antonio Vaquero Poblador, Felipe Checa, Adelardo Covarsí Yustas, and many others. The Institución Ferial de Badajoz (IFEBA), established in 2006, has not only become an important economic centre but has become a prominent regional cultural centre, and aside from trading it also regularly hosts cultural events from horse racing to break dancing to paintballing to Caribbean dancing.[31] The principal theatre in Badajoz is the Teatro López de Ayala, a grand white-painted theatre with arched windows with a capacity of 800 seats.[75] Performances of theatre, opera, concerts, and exhibitions are put on in the venue.

Like much of southern Spain, flamenco is very popular, and performances are regularly put on in Badajoz on the Plaza Alta and other venues. Some flamenco palos linked to Badajoz are Extremaduran jaleos and Extremaduran tangos. The classical music group Banda Municipal de Música, established in 1867, also performs at such venues in Badajoz and the wider province; as of 2013 it had 33 musicians.[76] In 1998 the municipal government established the Municipal School of Music in Badajoz (Escuelas Municipales de Música de Badajoz). As of 2013, classes are held in four venues in the public schools of Enrique Segura Covasí, Luis de Morales, Santo Tomás de Aquino and Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, teaching some 600 students.[77] The school teaches clarinet, flute, guitar, percussion, piano, saxophone, trumpet, violin, and singing. Cristóbal Oudrid (1825–1877), one of the founding fathers of Spanish musical nationalism, was born in Badajoz, son of the resident military bandmaster. Rosa Morena, a well-known flamenco-pop singer who was popular in the 1970s, was born in the city and still lives there; her most popular song is Échale guindas al pavo.

The festival known as "Feria de San Juan" is held every year from 23 June to 1 July at this border town, which is a major attraction not only for people of Spain but also to the Portuguese who cross the border to attend the one-week festival. This festival also includes bull fights.[38]

Badajoz is influenced by its border with Portugal. Portuguese restaurants and pastries can be found in the city, and residents often travel across the border for meals/excursions.

Badajoz is home to the Universidad de Extremadura (UNEX) Badajoz campus, situated on the west side of the river. The university was founded on 4 November 1968, when the Faculty of Badajoz belonging to the University of Seville was established.[78] Today, the University of Extremadura has branches in Badajoz, Cáceres, Mérida, and Plasencia. In 1971 the Council of Ministers approved the establishment of the College of Arts of Cáceres under the University of Salamanca. Secondary schools such as the Normal Schools of Education of Cáceres and Badajoz were integrated into the university in 1972 following the General Law of Education decree of 1970.[78] The Intermediate Technical School of Agricultural Engineering of Badajoz was founded in Badajoz 1968, renamed the College of Agricultural Engineering in 1972.[78]

Sports and recreation

Football

The city formerly hosted CD Badajoz, which dissolved in 2012 after finishing the season in Segunda División B Group 1.[79] Now, the city's main association football club is CD Badajoz 1905, a new club formed in 2012 by disappeared CD Badajoz supporters which is currently playing in the Regional Preferente in Extremadura, the fifth level of competition of the Spanish league football, after promotion in the 2012–13 season in the playoffs. Its stadium is Estadio Nuevo Vivero.

Cerro Reyes is currently unaffiliated with any league. Formerly, the club was a member of Segunda División B, having played their 2010–11 campaign in the division.[80] The club plays at Estadio José Pache.

Another football club based in Badajoz is Badajoz CF, a member of Tercera División – Group 14. UD Badajoz plays its home matches at Estadio Nuevo Vivero.[81]

Basketball

Badajoz's basketball club is AB Pacense, formed in 2005 from the remnants of Badajoz's dissolved basketball clubs, including CajaBadajoz, Círculo Badajoz, and Habitacle. The club competed in the Liga EBA, and calls Polideportivo La Granadilla its home arena.[82] The club was dissolved in summer 2013.

Golf

Badajoz plays host to two golf courses.[83] One, the Don Tello Golf Course, (إسپانية: Club de Golf de Mérida Don Tello), is a 9-hole course constructed in 1994. The course is described as "gentle and undulating", set on the banks of the Guadiana River.[84] The second, the Guadiana Golf Course, (إسپانية: Golf del Guadiana), is an 18-hole construct built in 1992. The course is described as challenging, in part due to the 14 lacustrine features and abundance of trees on the course.[85]

النقل

Badajoz railway station, (إسپانية: Estación de Tren de Badajoz), (IATA: BQZ), situated in the north of the city, is the only railway station at Badajoz. The station accommodates long-distance and medium-distance trains, both operated by the public company Renfe. It is the last Spanish railway station before the Portuguese railway system. It is expected the station will be replaced by a new facility located at the border with Portugal with high-speed services run by the Southwest–Portuguese corridor and the Madrid–Lisbon line. In August 2017 Comboios de Portugal, the Portuguese national railway company, instituted a daily service from Badajoz to Entroncamento, with connections to Lisbon and Porto.[86] [87][88]

Badajoz Airport, (إسپانية: Aeropuerto de Badajoz) (IATA: BJZ, ICAO: LEBZ), is located 13 km (8 mi) east of the city centre. The civilian airport shares a runway and control tower with Talavera la Real Air Base (إسپانية: Base Aérea de Talavera la Real) operated by the Spanish Air Force, named after the nearby municipality of Talavera la Real.[89] The two aircraft reception facilities utilize a 2,852-metre (9,257 ft) asphalt runway. The airport currently caters for two civil routes, one to Barcelona and the other to Madrid, both operated by Air Nostrum.[90]

أشخاص بارزون

- Pedro Acedo Penco (1955), politician

- Pedro de Alvarado (1485–1541), conquistador

- Estefanía Domínguez Calvo (born 1984), Spanish professional triathlete

- Manuel Godoy (1767–1851), Spanish Secretary of State

- Luis de Morales (1509–1586), painter[39]

- Rosa Morena (1941–2019), New flamenco singer

- Cristóbal Oudrid (1825–1877), pianist, conductor and composer

- Toñi Salazar (born 1963), Singer and composer

- Encarna Salazar (born 1961), Singer

- Juan Salazar (born 1954), Flamenco singer

- Enrique Salazar (1956–1982), Singer and composer

- José Salazar (1958) Singer and composer

- Pepa Bueno (1964) Newsreader, Journalist

- Hernando de Soto (1497-1542)conquistador

توأمة المدن

معرض الصور

View of the city of Badajoz from the Guadiana River.

الهامش

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Tarlow & Nilsson Stutz 2013, p. 377.

- ^ "Spain.info". Spain.info. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "DATOS ECONÓMICOS Y SOCIALES" (PDF) (in الإسبانية). Cajaespana.es. Archived from the original (PDF) on أبريل 5, 2014. Retrieved يوليو 12, 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت Ring, Salkin & La Boda 1995, p. 72.

- ^ Erskine 2012, p. 329.

- ^ Glick 1995, p. 6.

- ^ MacFarlane 2004, p. 127.

- ^ أ ب Melón, Miguel Ángel (2012). "Badajoz (1811–1812) La resistencia en la frontera" (PDF). In Butró Prída, Gonzalo; Rújula, Pedro (eds.). Los sitios en la guerra de la Independencia: La lucha en las ciudades. Cádiz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz. pp. 242–244. ISBN 978-84-9828-393-8.

- ^ أ ب Fletcher 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Press & Slater 2006, p. 180.

- ^ "Siege of Badajoz Archived ديسمبر 26, 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Treneer 1963, p. 133.

- ^ Museum of Foreign Literature, Science and Art. E. Littell. 1833. p. 612. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHistory - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Ring, Salkin & La Boda 1995, p. 74.

- ^ Kern 1995, p. 179.

- ^ Preston 2012, p. 318.

- ^ "Share on print Juan Yague". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت "The flood event that affected Badajoz in November 1997" (PDF). Advances in GeoSciences. 9 April 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Frey & Frey 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Yuste 1980, p. 208.

- ^ "Badajoz: Población por municipios y sexo" (in الإسبانية). INE. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "Guadiana del Caudillo celebra su primer año como independiente" (in الإسبانية). Badajoz7dias.com. Archived from the original on يوليو 29, 2013. Retrieved يوليو 11, 2013.

- ^ La población de Badajoz. Fundacion BBVA. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Lúcia 1986, p. 313.

- ^ "Badajoz" (in الإسبانية). Elecciones.mir.es. Archived from the original on February 23, 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Diario Oficial de Extremadura del 23 de febrero de 2012. Página 3943 Archived يوليو 2, 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Doe.juntaex.es, accessed 9 July 2013

- ^ Información comercial española: Boletín ICE económico (in الإسبانية). Ministerio de Economía. 2008. p. 270. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Knight 1854, p. 461.

- ^ أ ب "Ferias en España en IFEBA Institución Ferial de Badajoz". Portalferias.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Inicio" (in الإسبانية). Feria Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Caja Badajoz construye el edificio más alto de Extremadura para su sede social" (in الإسبانية). Elperiodicoextremadura.com. 9 July 2007. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Nueva Sede Corporativa de la Caja de Badajoz" (in الإسبانية). Portal.cajabadajoz.es. 18 November 2007. Archived from the original on June 12, 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ أ ب "Lusiberia". Lusiberia.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Frey & Frey 1995, p. 108.

- ^ Ring, Salkin & La Boda 1995, p. 73.

- ^ أ ب Kendrick, Michelson & Barbero 2008, p. 196.

- ^ أ ب Chisholm 1911, p. 181.

- ^ Kendrick, Michelson & Barbero 2008, p. 198.

- ^ "Plazas" (PDF) (in الإسبانية). Turismobadajoz.es. Archived from the original (PDF) on يوليو 15, 2013. Retrieved يوليو 14, 2013.

- ^ "Monuments: Alcazaba" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Tower Espantaperros" (in الإسبانية). Aytobadajoz.es. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Kendrick, Michelson & Barbero 2008, p. 199.

- ^ "Fortificación Vaubán". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Apuntes para la historia de la ciudad de Badajoz: ponencias y comunicaciones (in الإسبانية). Editora Regional de Extremadura. 1999. p. 75. ISBN 978-84-7671-470-6. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Torre de la Soledad y La Giralda" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "La Giralda, un millón de euros más barata". Hoy.es. January 14, 2012. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ أ ب "Puerta de Palmas" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Historia" (in الإسبانية). Clarisasbadajoz.com. Archived from the original on مايو 21, 2014. Retrieved يوليو 11, 2013.

- ^ "Gardens of La Galera". TripOrg. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Carvajal 2001, p. 21.

- ^ "The Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo (MEIAC)" (in الإسبانية). Official website of MEIAC. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "MEIAC – Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo". Art10.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "Museo de Bellas Artes" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamietno de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Museo Arqueológico" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Museo Catedralicio" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamietno de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Bullfighting Museum". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on يونيو 13, 2013. Retrieved أغسطس 6, 2013.

- ^ "Museum of Carnival in Badajoz" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on يونيو 13, 2013. Retrieved أغسطس 6, 2013.

- ^ "The Arrival of the City Regional" (PDF) (in الإسبانية). Dialnet Unirioja. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ "July". Pacodelucia.org. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Casa Álvarez-Buiza" (in الإسبانية). Turismobadajoz.es. Archived from the original on يونيو 20, 2013. Retrieved أغسطس 7, 2013.

- ^ "Ejemplos de Historicismo y sus variantes". Casa Álvarez-Buiza (in الإسبانية). monumentosdebadajoz.es. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "Casa Puebla" (in الإسبانية). Turismobadajoz.es. Archived from the original on يونيو 20, 2013. Retrieved أغسطس 7, 2013.

- ^ "Cementerio de Nuestra-senora-de-la-Soledad" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Cementerios Gestionados" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Los Cementerios de Badajoz Historia" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Los Cementerios de Badajoz Historia" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Sights (Badajoz)". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Bridges of Badajoz". Badajoz Ayer y Hoy. Archived from the original on أغسطس 12, 2013. Retrieved يوليو 14, 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت "Puente de Palmas". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Puente de la Universidad" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Puente de la Autonomía" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Puente Real" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Teatro López de Ayala" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Banda Municipal de Música" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Escuelas de Música" (in الإسبانية). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت "Cómo surgió la educación universitaria en Extremadura" (in الإسبانية). Unex.es. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "El CD Badajoz, condenado a Tercera". Hoy.es. July 2012. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Cerro Reyes". Footballdatabase.eu. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "La web del UD Badajoz". UD Badajoz. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Constituida la Asociación Pacense de Baloncesto". El Periodico Extremadura. September 16, 2005. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Badajoz Golf Course". WorldGolf. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "CLUB DE GOLF DE MÉRIDA DON TELLO". Spain.info. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "GOLF DEL GUADIANA, S.A." Spain.info. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Linha do Leste - Comboios Regionais 5500 e 5501| CP". Archived from the original on أغسطس 31, 2017. Retrieved أغسطس 31, 2017.

- ^ "High Speed Lines Madrid – Extremadura – Portuguese Border line". ADIF. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/passenger/single-view/view/entroncamento-badajoz-passenger-service-reinstated.html Archived 3 سبتمبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine Railway Gazette International

- ^ "Badajoz Airport". Airports Guides. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Badajoz Airport Routes". Aena Aeropuertos. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

وصلات خارجية

- نافذة على التاريخ الإسلامي لمدينة بداخوث الإسبانية

- Official website (in إسپانية)

- Universidad de Extremadura website (in إسپانية)

- Real Monasterio de Santa Ana website (in إسپانية)

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- صفحات تستخدم خطا زمنيا

- CS1 errors: empty citation

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using Template:Spain metadata Wikidata without references

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2008

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with إسپانية-language sources (es)

- الأندلس

- بلديات في بدخوث

- تأسيسات 875

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في القرن التاسع

- بلديات بطليوس

- صفحات مع الخرائط