شيشنق الرابع

| شوشنق الرابع | |

|---|---|

| فرعون مصر | |

| الحكم | 798–785 ق.م., الأسرة 22 |

| سبقه | شوشنق الثالث |

| تبعه | پامي |

هدجخپررع ستپإنرع شوشنق الرابع حكم مصر ضمن الأسرة 22 بين عهدي شوشنق الثالث و پامي. وفي 1986، اقترح ديڤد رول أن هناك ملكين بإسم شوشنق يحملان the prenomen هدجخپررع – (i) the well-known founder of the dynasty, هدجخپررع شوشنق الأول, and (ii) a later pharaoh from the second half of the dynasty, whom Rohl called هدجخپررع شوشنق (ب) due to his exact position in the dynasty being unknown.[2] Following Rohl's proposal (first suggested to him by Pieter Gert van der Veen in 1984), the British Egyptologist Aidan Dodson supported the new king’s existence by demonstrating that the earlier هدجخپررع شوشنق bore simple epithets in his titulary, whereas the later هدجخپررع شوشنق’s epithets were more complex.[3]

Dodson suggested that the ruler that Kenneth Kitchen, in his standard work on Third Intermediate Period chronology,[4] had numbered شوشنق الرابع – bearing the prenomen أوسرماعترع – should be removed from the 22nd Dynasty and replaced by Rohl's هدجخپررع شوشنق (ب), renumbering the latter as شوشنق الرابع. At the same time the old أوسرماعترع شوشنق الرابع was renumbered as شوشنق السادس. Dodson's historical summary لاكتشاف الملك الجديد شوشنق الرابع ودليله الداعم للوجود لذلك الملك باستقلال عن هدجخپررع شوشنق الأول ظهر في مقال حولي بعنوان ‘A New King Shoshenq Confirmed?’ ظهر في 1993.[5]

Rohl and Dodson's combined arguments for the existence of a new 22nd Dynasty Tanite king called هدجخپررع شوشنق الرابع are accepted by Egyptologists today, including يورگن فون بكرات and كنث كتشن – the latter in the preface to the third edition of his book on The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt.[6]

وكما يشير دودسون، فبينما شوشنق الرابع shared the same prenomen as his illustrious ancestor شوشنق الأول، he is distinguished from شوشنق الأول by his use of an especially long nomen – شوشنق-مريآمون سيباست نتجرهقعإيونو which featured both the sibast ('ابن باست') و نتجرهقعإيونو ('الحاكم الإله [لمدينة] "أون" ') epithets.[7] These two epithets were only gradually employed by the 22nd Dynasty pharaohs، بدءا من عهد أوسوركون الثاني. By contrast, Shoshenq I’s nomen simply reads ‘شوشنق-مريآمون’. Shoshenq I's immediate successors, أوسوركون الأول و تاكلوت الأول also never used epithets beyond the standard ‘مريآمون’ (محبوب آمون). In his 1994 book on the Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt, Dodson perceptively observes that when the sibast epithet ‘appears during the dynasty of Osorkon II’, it is rather infrequent, while the netjerheqawaset ('الحاكم الإله لطيبة') and netjerheqaon epithets are only exclusively attested ‘in the reigns of that monarch’s successors’ – that is شوشنق الثالث و پامي و شوشنق الخامس.[8] This suggests that the newly identified هدجخپررع شوشنق الرابع was a late Tanite-era king who ruled in Egypt either أثناء أو بعد حكم شوشنق الثالث.

Rohl had already pointed out in 1989 that the cartouches of a هدجخپررع شوشنق appear on a stela (St. Petersburg Hermitage 5630) dated to Year 10 of the king.[9] This stela mentions a Great Chief of the Libu, Niumateped, who is also attested in a Year 8, usually attributed to Shoshenq V. Since the title ‘Chief of the Libu’ is only documented from Year 31 of Shoshenq III onwards, it seems this new king must have ruled بالتزامن مع أو بعد شوشنق الثالث. Dodson noted that the هدجخپررع شوشنق on the stela bore the long form titulary, now attributed to هدجخپررع شوشنق الرابع، thus confirming that the stela cannot be dated to هدجخپررع شوشنق الأول.[10]

In his 1993 paper, Dodson proposed to place Shoshenq IV's reign after the last attested regnal date for Shoshenk III in Year 39, arguing that the discovery of Shoshenq IV’s burial in the tomb of Shoshenq III at Tanis makes it likely that he was part of the 22nd Dynasty Tanite line. Dodson would therefore place هدجخپررع شوشنق الرابع بين شوشنق الثالث و پامي.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الدفن

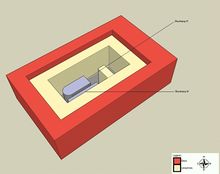

أعمال الحفريات في مقبرة NRT V التانيسية المنهوبة لشوشنق الثالث تبين وجود تابوتين: one inscribed for Usermaatre-setepenre Shoshenq III and the other being an anonymous sarcophagus. The unmarked sarcophagus, however, ‘was clearly a secondary introduction’ according to its position in the tomb.[11] In the Tanite tomb’s debris, several fragments were found from one or two canopic jars bearing the cartouches of a هدجخپررع شوشنق. Rohl had pointed out that the Staatliche Museum in Berlin possessed a canopic chest for هدجخپررع شوشنق الأول and that these jars من مقبرة شوشنق الثالث were too large to fit inside the Berlin canopic chest. Rohl ‘used the evidence of the jars as the key element of his theory that there were indeed two هدجخپررع شوشنق’.[7] Dodson noted that the Tanite canopic vessels bear the name ‘هدجخپررع-ستپإنرع-مريآمون-سيباست-نتجرهقعإيونو’ and, since the epithet نتجرهقعإيونو ('god ruler of Heliopolis') was never employed by the 22nd Dynasty kings until the reign of Shoshenq III, this is clear evidence that the new Shoshenq IV was buried in Shoshenq III's Tanite tomb and must have succeeded this king.[12] It also establishes that the king buried in the second sarcophagus in Shoshenq III's tomb was certainly not Shoshenq I. Dodson was initially reluctant to accept Rohl's proposal for a second Hedjkheperre Shoshenk but his own research into the archaeological evidence led him to revise his opinion:

“Having implicitly rejected such a conclusion in 1986, further study of the canopic fragments as part of my general treatment of royal canopics has now led me rather to support the existence of two Shoshenqs with the prenomen هدجخپررع.”[7] وهذا هو الآن إجماع التيار الرئيسي في علم المصريات.

الهامش

- ^ يورگن فون بكرات، Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen (= Münchner ägyptologische Studien, vol 46), Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1999. ISBN 3-8053-2310-7, pp.190-91.

- ^ D. Rohl: ‘Questions and Answers on the Chronology of Rohl and James’, Chronology & Catastrophism Workshop 1986:1, p. 22.

- ^ A. Dodson: ‘A new King Shoshenq confirmed?’, Göttinger Miszellen 137 (1993), pp.53-58.

- ^ K. A. Kitchen: The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 ق.م.), 1st edition (1973), p.87.

- ^ A. Dodson, op. cit.

- ^ K. A. Kitchen: The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 ق.م.), 3rd edition (1996), § Y p.xxvi

- ^ أ ب ت A. Dodson, op. cit. (1993), p.55.

- ^ A. Dodson: The Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt (1994), p. 93.

- ^ D. Rohl: ‘The Early Third Intermediate Period: Some Chronological Considerations’, Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum 3 (1989), pp.66-67.

- ^ A. Dodson, op.cit. (1993), pp.55-56.

- ^ A. Dodson, op.cit. (1994), p. 93.

- ^ A. Dodson, op. cit. (1993), pp.54-55

- Aidan Dodson, "A new King Shoshenq confirmed?" GM 137(1993), pp.53-58.

- Aidan Dodson, "The Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt," (Kegan Paul Intl: 1994)

- J. Yoyotte, Melanges Maspero I:4 (Cairo:1961), pp.142-43 [Comment on the Year 10 Shoshenq Si-Bast stela].

- Great Chiefs of the Libu: Niumateped

| سبقه شوشنق الثالث |

فرعون مصر 798 - 785 ق.م. الأسرة المصرية الثانية والعشرون |

تبعه پامي |