جد كا رع إيسسي

| جد كا رع إيسسي Djedkare Isesi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tankeris | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

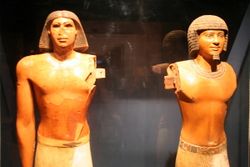

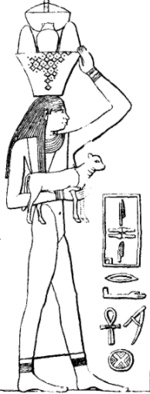

Relief of Djedkare Isesi, Egyptian Museum of Berlin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| فرعون | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحكم | duration uncertain, at least 33 years and possibly more than 44 years, in the late-25th to mid-24th century BCE.[note 1] (الأسرة الخامسة) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | من كاو حور | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تبعه | اوناس | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| القرينة | ربما Meresankh IV؟ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأنجال | Neserkauhor ♂, Kekheretnebti ♀, Meret-Isesi ♀, Hedjetnebu ♀, Nebtyemneferes ♀ Uncertain: Raemka ♂, Kaemtjenent ♂, Isesi-ankh ♂ Conjectural: Unas ♂ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المدفن | هرم جد كا رع إسسي | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

جد كا رع إسسي بالإنجليزية Djedkare Isesi ، وباليونانية تانخريس [17] ، هو الملك الثامن من ملوك الأسرة الخامسة في أواخر القرن الخامس والعشرين وحتى منتصف القرن الرابع والعشرين ق.م. في الدولة المصرية القديمة. وقد أتى إسسي بعد الملك من كاو حور كايو الذى أرسل حملة الى شبه جزيرة سيناء. وخلف إسسي الفرعون اوناس. وعلاقته بهذين الفرعونين تبقى غير واضحة، بالرغم من أنه يُستدل أن اوناس كان ابن جد كا رع لكون انتقال السلطة بينهما كان سلساً.

Djedkare likely enjoyed a long reign of more than 40 years, which heralded a new period in the history of the Old Kingdom. Breaking with a tradition followed by his predecessors since the time of Userkaf, Djedkare did not build a temple to the sun god Ra, possibly reflecting the rise of Osiris in the Egyptian pantheon. More significantly, Djedkare effected comprehensive reforms of the Egyptian state administration, the first undertaken since the inception of the system of ranking titles. He also reorganised the funerary cults of his forebears buried in the necropolis of Abusir and reformed the corresponding priesthood. Djedkare commissioned expeditions to Sinai to procure copper and turquoise, to Nubia for its gold and diorite and to the fabled Land of Punt for its incense. One such expedition had what could be the earliest recorded instance of oracular divination undertaken to ensure an expedition's success. The word "Nub", meaning gold, to designate Nubia is first recorded during Djedkare's reign. Under his rule, Egypt also entertained continuing trade relations with the Levantine coast and made punitive raids in Canaan. In particular, one of the earliest depictions of a battle or siege scene was found in the tomb of one of Djedkare's subjects.

Djedkare was buried in a pyramid in Saqqara named Nefer Djedkare ("Djedkare is perfect"), which is now ruined owing to theft of stone from its outer casing during antiquity. The burial chamber still held Djedkare's mummy when it was excavated in the 1940s. Examinations of the mummy revealed that he died in his fifties. Following his death, Djedkare was the object of a cult that lasted at least until the end of the Old Kingdom. He seemed to have been held in particularly high esteem during the mid-Sixth Dynasty, whose pharaohs lavished rich offerings on his cult. Archaeological evidence suggests the continuing existence of this funerary cult throughout the much later New Kingdom period (c. 1550–1077 ق.م.). Djedkare was also remembered by the Ancient Egyptians as the king of vizier Ptahhotep, the purported author of The Maxims of Ptahhotep, one of the earliest pieces of philosophic wisdom literature.

The reforms implemented by Djedkare are generally assessed negatively in modern Egyptology as his policy of decentralization created a virtual feudal system that transferred much power to the high and provincial administrations. Some Egyptologists such as Naguib Kanawati argue that this contributed heavily to the collapse of the Egyptian state during the First Intermediate Period, c. 200 years later. These conclusions are rejected by Nigel Strudwick, who says that in spite of Djedkare's reforms, Ancient Egyptian officials never amassed enough power to rival that of the king.

والواضح أن عصر إسسي كان عصراً حافلا بالأعمال العظيمة وقد أحضر قزما من نوع نادر من بلاد بنط (الصومال) وأرسل حملة الى سيناء ومن الطريف أن پتاح حتپ صاحب التعاليم المشهورة التى تعد أقدم ما وصل من حـِكم المصريين كان مربي الملك إسسي. وقد إلتمس الحكيم من الملك إسسي أن يقوم إبنه بنفس وظيفته واجابه الملك الى طلبه وقد مكث أسيس ما يقرب من 28 سنة على العرش.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

العائلة

الأبوان

الملكات

الأبناء

البنات

التزمين

سنوات الحكم

| الخبير | سنوات الحكم |

|---|---|

| ردفورد | 2436 ق.م. - 2404 ق.م. |

| شو | 2414 ق.م. - 2375 ق.م. |

| دودسون | 2413 ق.م. - 2485 ق.م. |

| شنايدر | 2410 ق.م. - 2380 ق.م. |

| كراوس | 2410 ق.م. - 2380 ق.م. |

| ألن | 2381 ق.م. - 2353 ق.م. |

| فون بكراث | 2380 ق.م. - 2342 ق.م. |

| مالك | 2369 ق.م. - 2341 ق.م. |

الحكم

الإصلاحات المحلية

أنشطة العمران

الأنشطة خارج مصر

التجريدات إلى المناجم والمحاجر

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

العلاقات التجارية

Egypt entertained continuing trade relations with the Levant during Djedkare's reign, possibly as far north as Anatolia. A gold cylinder seal bearing the serekh of Djedkare Isesi together with the cartouche of Menkauhor Kaiu is now on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[note 3][25] The seal, whose gold may originate from the Pactolus river valley in western Anatolia,[26] could attest to wide-ranging trade-contacts during the later Fifth Dynasty,[2][27] but its provenance remains unverifiable.[note 4][30]

Trade contacts with Byblos, on the coast of modern-day Lebanon, are suggested by a fragmentary stone vessel unearthed in the city and bearing the inscription "King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Djedkare [living] forever".[31][32] A biographical inscription discovered in the tomb of Iny, a Sixth Dynasty official, provides further evidence for an Egyptian expedition to Byblos during Djedkare's reign.[33] Iny's inscription relates his travels to procure lapis lazuli and lead or tin[34] for pharaoh Merenre, but starts by recounting what must have been similar events taking place under Djedkare.[35]

To the south of Egypt, Djedkare also sent an expedition to the fabled land of Punt[36] to procure the myrrh used as incense in the Egyptian temples.[37] The expedition to Punt is referred to in the letter from Pepi II Neferkare to Harkuf some 100 years later. Harkuf had reported that he would bring back a "dwarf of the god's dancers from the land of the horizon dwellers". Pepi mentions that the god's sealbearer Werdjededkhnum had returned from Punt with a dwarf during the reign of Djedkare Isesi and had been richly rewarded. The decree mentions that "My Majesty will do for you something greater than what was done for the god's sealbearer Werdjededkhnum in the reign of Isesi, reflecting my majesty's yearning to see this dwarf".[38]

Djedkare's expedition to Punt is also mentioned in a contemporaneous graffito found in Tumas, a locality of Lower Nubia some 150 km (93 mi) south of Aswan,[40] where Isesi's cartouche was discovered.[41]

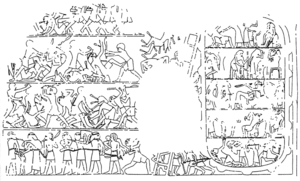

القتال

Not all relations between Egypt and its neighbors were peaceful during Djedkare's reign. In particular, one of the earliest known depictions of a battle or city being besieged[42] is found in the tomb of Inti, an official from the 21st nome of Upper Egypt, who lived during the late Fifth Dynasty.[33][42] The scene shows Egyptian soldiers scaling the walls of a near eastern fortress on ladders.[40][43] More generally, ancient Egyptians seem to have regularly organised punitive raids in Canaan during the later Old Kingdom period but did not attempt to establish a permanent dominion there.[44]

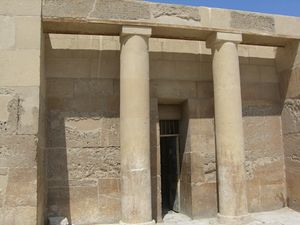

الهرم

Djedkare built his pyramid in South Saqqara. It was called Nefer Isesi or Nefer Djedkare in Ancient Egyptian,[note 5][45] variously translated as "Isesi/Djedkare is beautiful"[46] or "Isesi/Djedkare is perfect".[2][9] It is known today as "Haram el-Shawwâf El-Kably",[45] meaning "the Southern Sentinel pyramid", because it stands on the edge of the Nile valley.[47][48]

ذكراه

وقع الإصلاحات

For Nigel Strudwick, the reforms of Djedkare Isesi were undertaken as a reaction to the rapid growth of the central administration in the first part of the Fifth Dynasty[49] which, Baer adds, had amassed too much political or economic power[50] in the eyes of the king.[51]

العبادة الجنائزية

المملكة القديمة

المملكة الحديثة

The funerary cult of Djedkare Isesi enjoyed a revival during the New Kingdom (ح. 1550–1077 ق.م.). For the early part of this period, this is best attested by the Karnak king list, a list of kings commissioned by pharaoh Thutmose III. The list was not meant to be exhaustive, rather it gave the names of Thutmose's forefathers whom he wanted to honor by dedicating offerings.[53]

For the later New Kingdom, a relief from the Saqqara tomb of the priest Mehu, dating to the 19th or 20th Dynasty shows three gods faced by several deceased pharaohs. These are Djoser and Sekhemket, of the Third Dynasty and Userkaf, founder of the Fifth Dynasty. He is followed by a fourth king whose name is damaged but which is often read "Djedkare" or, much less likely, "Shepseskare". The relief is an expression of personal piety on Mehu's behalf, who prayed to the ancient kings for them to recommend him to the gods.[54]

انظر أيضا

وصلات خارجية

- Egyptian Kings

- The Instruction of Ptahhotep Index Page (Prisse Papyrus)

- The Mastaba of Ptahhotep reliefs from his tomb (Prisse Papyrus)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ملاحظات

- ^ Proposed dates for Djedkare Isesi's reign: 2436–2404 BCE,[1][2][3] 2414–2375 BCE[4][5][6][7][8] 2405–2367 BCE,[9] 2380–2342 BCE,[10] 2379–2352 BCE,[11] 2365–2322 BCE.[12]

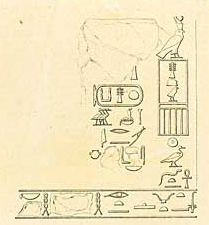

- ^ The inscription reads "First occasion of the Sed festival of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Djedkare, beloved of the bas of Heliopolis, given life, stability, and all joy for ever."[19][20]

- ^ The golden seal has the catalog number 68.115.[25]

- ^ The provenance of the seal is usually believed to be a tomb in a yet undiscovered site along the Eastern Mediterranean coast.[28] The archaeologist Karin Sowada however doubts the authenticity of the seal.[29]

- ^ Transliterations nfr-Jzzj and nfr-Ḏd-k3-Rˁ.[45]

المصادر

- ^ Verner 2001b, p. 589.

- ^ أ ب ت Altenmüller 2001, p. 600.

- ^ Hawass & Senussi 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Malek 2000, p. 100.

- ^ Rice 1999, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Clayton 1994, pp. 60.

- ^ Sowada & Grave 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Lloyd 2010, p. xxxiv.

- ^ أ ب Strudwick 2005, p. xxx.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 60–61 & 283.

- ^ Strudwick 1985, p. 3.

- ^ Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Leprohon 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 61.

- ^ Leprohon 2013, Footnote 63.

- ^ Mariette 1864, p. 15.

- ^ Miroslav Verner, Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001, pp.405

- ^ Mariette 1885, p. 191.

- ^ Strudwick 2005, p. 130.

- ^ Sethe 1903, text 57.

- ^ Louvre Museum, Online Collection 2016, Item E5323.

- ^ Petrie, Weigall & Saba 1902, plate LV, num 2.

- ^ Strudwick 1985, p. 301.

- ^ Lepsius Denkmäler II, p. 2 & 39.

- ^ أ ب ت Seal of office 68.115, BMFA 2015.

- ^ Young 1972, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Vermeule, Stone & Vermeule 1970, p. 34.

- ^ Vermeule, Stone & Vermeule 1970, p. 37.

- ^ Sowada & Grave 2009, p. 146, footnote 89.

- ^ Schulman 1979, p. 86.

- ^ Nelson 1934, pl. III no. 1, see here and there.

- ^ Porter, Moss & Burney 1951, p. 390.

- ^ أ ب Verner 2001b, p. 590.

- ^ Marcolin 2006, footnote f.

- ^ Marcolin 2006, p. 293.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 79.

- ^ Hayes 1978, p. 67.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Petrie 1898, plate IV.

- ^ أ ب Baker 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Weigall 1907, Pl. LVIII.

- ^ أ ب Strudwick 2005, p. 371.

- ^ Kanawati & McFarlane 1993, pl. 2.

- ^ Redford 1992, pp. 53–54.

- ^ أ ب ت Porter et al. 1981, p. 424.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 118.

- ^ Leclant 1999, p. 865.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 153.

- ^ Strudwick 1985, p. 340.

- ^ Strudwick 1985, p. 341.

- ^ Baer 1960, p. 297 & 300.

- ^ Murray 1905, pl. IX.

- ^ Wildung 1969, pp. 60–63.

- ^ Wildung 1969, pp. 74–76.

وصلات خارجية

- سليم حسن (1992). موسوعة مصر القديمة. الهيئة العامة للكتاب.

- قالب:اعلام قدماء المصريين

- Miroslav Verner, Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001, pp.405-410 (coverage of Djedkare Isesi's reign)

| سبقه من كاو حور |

فرعون مصر الأسرة الخامسة |

تبعه اوناس |