مملكة خوتان

مملكة خوتان | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56–1006 | |||||||||

مملكة خوتان كما كانت في 1001 م | |||||||||

| الحالة | امبراطورية | ||||||||

| Capital | يوتكان | ||||||||

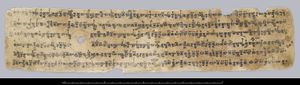

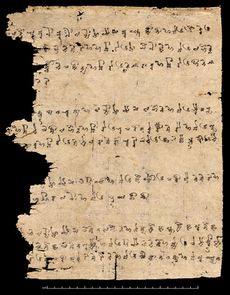

| اللغات المشتركة | گندهاري القرن الثالث والرابع.[web 1] الخوتانية، التي هي لهجة من لغة ساكا، بتنويع من الكتابة البراهمية.[web 2] | ||||||||

| الدين | البوذية | ||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية | ||||||||

• ح. 56 | يولين: فترة جيانوو (25–56 م) | ||||||||

• 969 | Nanzongchang (الأخير) | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

• تأسيس خوتان | ح. 300 ق.م. | ||||||||

• Established | 56 | ||||||||

| 56 | |||||||||

• التبت تغزو وتهزم خوتان | 670 | ||||||||

• خوتان يحتفظ بها المسلمون، بقيادة يوسف قادر خان | 1006 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1006 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ شينجيانگ |

|

مملكة خوتان Kingdom of Khotan كانت مملكة بوذية قديمة لشعب ساكا الإيراني وتقع على فرع لطريق الحرير يمتد على حافة صحراء تكلامكان في حوض تريم (شينجيانگ الحديثة، بالصين). العاصمة القديمة كانت تقع في الأصل إلى الغرب من هوتان الحالية (الصينية: 和田) عند يوتكان.[1][2] ومنذ أسرة هان حتى على الأقل أسرة تانگ، كانت تُعرف في الصينية بإسم يوتيان (الصينية: 于闐، 于窴, أو 於闐). تواجدت هذه المملكة البوذية لحدٍ كبير لأكثر من ألف سنة حتى اجتاحتها القرةخانات المسلمة في 1006، أثناء أسلمة وتتريك شينجيانگ.

لما كانت قد بُنيت على واحات، فقد سمحت بساتين التوت في خوتان بإنتاج وتصدير الحرير والسجاد، بالإضافة إلى المنتجات الرئيسية الأخرى في المدينة مثل يشم النفريت المشهور والفخار. على الرغم من كونها مدينة مهمة على طريق الحرير بالإضافة إلى كونها مصدرًا بارزًا لليشم في الصين القديمة، إلا أن خوتان نفسها صغيرة نسبيًا - كان محيط مدينة خوتان القديمة في يوتكان حوالي 2.5 إلى 3.2 كيلومتر (1.5 إلى 2 ميل). ومع ذلك، فقد تم القضاء على الكثير من الأدلة الأثرية لمدينة خوتان القديمة بسبب قرون من البحث عن الكنوز من قبل السكان المحليين.[3]

استخدم سكان خوتان الخوتانية، اللغة الإيرانية الشرقية، وگندهاري پراكريت، اللغة الهندو-آرية المرتبطة بالسنسكريتية. وهناك جدل حول كم كان السكان الأصليون في خوتان مرتبطين عرقياً وأنثروبولوجياً بجنوب آسيا والمتحدثين بلغة الگندهاري مقابل الساكا، وهم شعب هندو-أوروپي من الفرع الإيراني من السهوب الأوراسية. من القرن الثالث فصاعدًا، كان لهم أيضًا تأثير لغوي واضح على لغة گندهاري المستخدَمة في البلاط الملكي في خوتان. كما تم التعرف أيضًا على لغة ساكا الخوتانية كلغة بلاط رسمية بحلول القرن العاشر واستخدمها الحكام الخوتانيون لتوثيق الإداري.

الأسماء

The kingdom of Khotan was given various names and transcriptions, and the name as written by the locals also changed over time. In about the third century AD, the local people wrote Khotana in Kharoṣṭhī script, and Hvatäna in the Brahmi script some time later. From this came Hvamna and Hvam in their latest texts, where Hvam kṣīra or 'the land of Khotan' was the name given. Khotan became known to the west while the –t- was still unchanged, as is frequent in early New Persian. The local people also used Gaustana (Gosthana, Gostana, Godana, Godaniya or Kustana) under the influence of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, and Yūttina in the ninth century, when it was allied with the Chinese kingdom of Șacū (Shazhou or Dunhuang).[4][5]

The ancient Chinese called Khotan Yutian (于闐, its ancient pronunciation was gi̯wo-d'ien or ji̯u-d'ien)[3] also written as 于窴 and other similar-sounding names such as Yudun (于遁), Huodan (豁旦), and Qudan (屈丹). Sometimes they also used Jusadanna (瞿薩旦那), derived from Indo-Iranian Gostan and Gostana, the names of the town and region around it respectively. Others include Huanna (渙那).[6] To the Tibetans in the seventh and eighth centuries, the kingdom was called Li (or Li-yul) and the capital city Hu-ten, Hu-den, Hu-then and Yvu-then.[4][7]

التاريخ

From an early period, the Tarim Basin had been inhabited by different groups of Indo-European speakers such as the Tocharians and Saka people.[8][9] Jade from Khotan had been traded into China for a long time before the founding of the city, as indicated by items made of jade from Khotan found in tombs from the Shang (Yin) and Zhou dynasties. The jade trade is thought to have been facilitated by the Yuezhi.[10]

أسطورة التأسيس

There are four versions of the legend of the founding of Khotan,[11] these may be found in accounts given by the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang and in Tibetan translations of Khotanese documents. All four versions suggest that the city was founded around the third century BC by a group of Indians during the reign of Ashoka.[3][11] According to one version, the nobles of a tribe in ancient Taxila, who traced their ancestry to the deity Vaiśravaṇa, were said to have blinded Kunãla, a son of Ashoka. In punishment they were banished by the Mauryan emperor to the north of the Himalayas, where they settled in Khotan and elected one of their members as king. However war then ensued with another group from China whose leader then took over as king, and the two colonies merged.[3] In a different version, it was Kunãla himself who was exiled and founded Khotan.[12]

وصول الساكا

Han influence on Khotan, however, would diminished when Han power declined.[web 3]

أسرة تانگ

|

| |

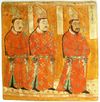

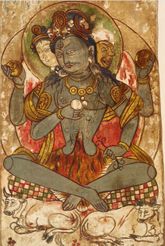

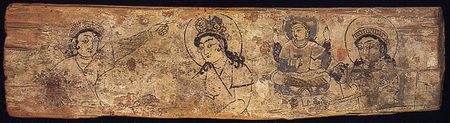

Paintings by the Khotanese artist Yuchi Yiseng or his father Yuchi Bazhina (尉遲跋質那), Tang dynasty (618-907 AD)

Left: painting of an Indian deity on the obverse of a painted panel, most likely depicting Shiva Right: painting of a Persian deity on the reverse of a painted panel, probably depicting the legendary hero Rustam | ||

The Tang campaign against the oasis states began in 640 AD and Khotan submitted to the Tang emperor. The Four Garrisons of Anxi were established, one of them at Khotan.

The Tibetans later defeated the Chinese and took control of the Four Garrisons. Khotan was first taken in 665,[14] and the Khotanese helped the Tibetans to conquer Aksu.[15] Tang China later regained control in 692, but eventually lost control of the entire Western Regions after it was weakened considerably by the An Lushan Rebellion.

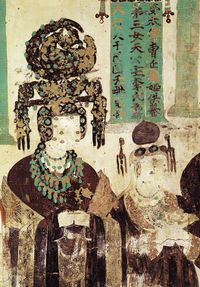

After the Tang dynasty, Khotan formed an alliance with the rulers of Dunhuang. The Buddhist entitites of Dunhuang and Khotan had a tight-knit partnership, with intermarriage between Dunhuang and Khotan's rulers and Dunhuang's Mogao grottos and Buddhist temples being funded and sponsored by the Khotan royals, whose likenesses were drawn in the Mogao grottoes.[16]

Khotan was conquered by the Tibetan Empire in 792 and gained its independence in 851.[17]

الفتح التوركي-الإسلامي لخوتان البوذية

In the 10th century, the Iranic Saka Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan was the only city-state that was not conquered yet by the Turkic Uyghur (Buddhist) and the Turkic Qarakhanid (Muslim) states. During the latter part of the tenth century, Khotan became engaged in a struggle against the Kara-Khanid Khanate. The Islamic conquests of the Buddhist cities east of Kashgar began with the conversion of the Karakhanid Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan to Islam in 934. Satuq Bughra Khan and later his son Musa directed endeavors to proselytize Islam among the Turks and engage in military conquests,[16][18] and a long war ensued between Islamic Kashgar and Buddhist Khotan.[19] Satuq Bughra Khan's nephew or grandson Ali Arslan was said to have been killed during the war with the Buddhists.[20] Khotan briefly took Kashgar from the Kara-Khanids in 970, and according to Chinese accounts, the King of Khotan offered to send in tribute to the Chinese court a dancing elephant captured from Kashgar.[21]

Accounts of the war between the Karakhanid and Khotan were given in Taẕkirah of the Four Sacrificed Imams, written sometime in the period from 1700-1849 in the Eastern Turkic language (modern Uyghur) in Altishahr probably based on an older oral tradition. It contains a story about four Imams from Mada'in city (possibly in modern-day Iraq) who helped the Qarakhanid leader Yusuf Qadir Khan conquered Khotan, Yarkand, and Kashgar.[22] There were years of battles where "blood flows like the Oxus", "heads litter the battlefield like stones" until the "infidels" were defeated and driven towards Khotan by Yusuf Qadir Khan and the four Imams. The imams however were assassinated by the Buddhists prior to the last Muslim victory.[23] Despite their foreign origins, they are viewed as local saints by the current Muslim population in the region.[24] In 1006, the Muslim Kara-Khanid ruler Yusuf Kadir (Qadir) Khan of Kashgar conquered Khotan, ending Khotan's existence as an independent Buddhist state.[16] Some communications between Khotan and Song China continued intermittently, but it was noted in 1063 in a Song source that the ruler of Khotan referred to himself as kara-khan, indicating dominance of the Karakhanids over Khotan.[25]

It has been suggested Buddhists in Dunhuang, alarmed by the conquest of Khotan and ending of Buddhism there, sealed Cave 17 of the كهوف موگاو containing the Dunhuang manuscripts so to protect them.[26] الكاتب المسلم التوركي القراخاني محمود القشغري سجـَّل قصيدة قصيرة بلغة توركية عن الفتح:

kälginläyü aqtïmïz

kändlär üzä čïqtïmïz

furxan ävin yïqtïmïz

burxan üzä sïčtïmïzWe came down on them like a flood,

We went out among their cities,

We tore down the idol-temples,

We shat on the Buddha's head!

According to Kashgari who wrote in the 11th century, the inhabitants of Khotan still spoke a different language and did not know the Turkic language well.[32][33] It is however believed that the Turkic languages became the lingua franca throughout the Tarim Basin by the end of the 11th century.[34]

By the time Marco Polo visited Khotan, which was between 1271 and 1275, he reported that "the inhabitants all worship Mohamet."[35][36]

خط زمني

- أول سكان المنطقة يبدو أنهم كانوا هنوداً من امبراطورية موريا حسب أساطير تأسيسها.[3]

- The first inhabitants of the region appear to have been Indians from the Maurya Empire according to its founding legends.[3]

- The foundation of Khotan occurred when Kushtana, said to be a son of Ashoka, the Indian emperor belonging to the Maurya Empire settled there about 224 BC.[37]

- c.84 BC: Buddhism is reportedly introduced to Khotan.[38]

- c.56: Xian, the powerful and prosperous king of Yarkent, attacked and annexed Khotan. He transferred Yulin, its king, to become the king of Ligui, and set up his younger brother, Weishi, as king of Khotan.

- 61: Khotan defeats Yarkand. Khotan becomes very powerful after this and 13 kingdoms submitted to Khotan, which now, with Shanshan, became the major power on the southern branch of the Silk Route.

- 78: Ban Chao, a Chinese General, subdues the kingdom.

- 127: The Khotanese king Vijaya Krīti is said to have helped the Kushan Emperor Kanishka in his conquest of Saket in India.

- 127: The Chinese general Ban Yong attacked and subdued Karasahr; and then Kucha, Kashgar, Khotan, Yarkand, and other kingdoms, seventeen altogether, who all came to submit to China.

- 129: Fangqian, the king of Khotan, killed the king of Keriya, Xing. He installed his son as the king of Keriya. Then he sent an envoy to offer tribute to Han. The Emperor pardoned the crime of the king of Khotan, ordering him to hand back the kingdom of Keriya. Fangqian refused.

- 131: Fangqian, the king of Khotan, sends one of his sons to serve and offer tribute at the Chinese Imperial Palace.

- 132: The Chinese sent the king of Kashgar, Chenpan, who with 20,000 men, attacked and defeated Khotan. He beheaded several hundred people, and released his soldiers to plunder freely. He replaced the king [of Keriya] by installing Chengguo from the family of [the previous king] Xing, and then he returned.

- 151: Jian, the king of Khotan, was killed by Han chief clerk Wang Jing, who was in turn killed by Khotanese. Anguo, the son of Jian, was placed on the throne.

- 175: Anguo, the king of Khotan, attacked Keriya, and defeated it soundly. He killed the king and many others.[39]

- 195: The 'Western Regions' rebelled, and Khotan regained its independence.

- 399 Chinese pilgrim monk, Faxian, visits and reports on the active Buddhist community there.[40]

- 632: Khotan pays homage to imperial China, and becomes a vassal state.

- 644: Chinese pilgrim monk, Xuanzang, stays 7–8 months in Khotan and writes a detailed account of the kingdom.

- 670: Tibetan Empire invades and conquers Khotan (now known as one of the "four garrisons").

- c.670-673: Khotan governed by Tibetan Mgar minister.

- 674: King Fudu Xiong (Vijaya Sangrāma IV), his family and followers flee to China after fighting the Tibetans. They are unable to return.

- c.680 - c.692: 'Amacha Khemeg rules as regent of Khotan.

- 692: China under Wu Zetian reconquers the Kingdom from Tibet. Khotan is made a protectorate.

- 725: Yuchi Tiao (Vijaya Dharma III) is beheaded by the Chinese for conspiring with the Turks. Yuchi Fushizhan (Vijaya Sambhava II) is placed on the throne by the Chinese.

- 728: Yuchi Fushizhan (Vijaya Sambhava II) officially given the title "King of Khotan" by the Chinese emperor.

- 736: Fudu Da (Vijaya Vāhana the Great) succeeds Yuchi Fushizhan and the Chinese emperor bestows a title on his wife.

- c. 740: King Yuchi Gui (وايلي: btsan bzang btsan la brtan) succeeds Fudu Da (Vijaya Vāhana) and begins persecution of Buddhists. Khotanese Buddhist monks flee to Tibet, where they are given refuge by the Chinese wife of King Mes ag tshoms. Soon after, the queen died in a smallpox epidemic and the monks had to flee to Gandhara.[41]

- 740: Chinese emperor bestows a title on wife of Yuchi Gui.

- 746: The Prophecy of the Li Country is completed and later added to the Tibetan Tengyur.

- 756: Yuchi Sheng hands over the government to his younger brother, Shihu (Jabgu) Yao.

- 786 to 788: Yuchi Yao still ruling Khotan at the time of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Wukong's visit to Khotan.[42]

- 934: Viśa' Saṃbhava marries the daughter of Cao Yijin, the ruler of the Guiyi Circuit of Dunhuang.

- 969: The son of King Viśa' Saṃbhava named Zongchang sends a tribute mission to China.

- 971: A Buddhist priest (Jixiang) brings a letter from the king of Khotan to the Chinese emperor offering to send a dancing elephant which he had captured from Kashgar.

- 1006: Khotan held by the Muslim Yūsuf Qadr Khān, a brother or cousin of the Muslim ruler of Kāshgar and Balāsāghūn.[43]

- Between 1271 and 1275: Marco Polo visits Khotan.[44]

الحكام

(Some names are in modern Mandarin pronunciations based on ancient Chinese records)

- Yu Lin (俞林) 23

- Jun De (君得) 57

- Xiu Moba (休莫霸) 60

- Guang De (廣德) 60

- Fang Qian (放前) 110

- Jian (建) 132

- An Guo (安國) 152

- Qiu Ren (秋仁) 446

- Polo the Second (婆羅二世) 471

- Sanjuluomo the Third (散瞿羅摩三世) 477

- She Duluo (舍都羅) 500

- Viśa' (尉遲) 530

- Bei Shilian (卑示練) 590

- Viśa' Wumi (尉遲屋密) 620

- Fudu Xin (伏闍信) 642

- Fudu Xiong (伏闍雄) 665

- Viśa' Jing (尉遲璥) 691

- Viśa' Tiao (尉遲眺) 724

- Fu Shizhan (伏師戰) 725

- Fudu Da (伏闍達) 736

- Viśa' Gui (尉遲珪) 740

- Viśa' Sheng (尉遲勝) 745

- Viśa' Vāhaṃ (尉遲曜) 764

- Viśa' Jie (尉遲詰) 791

- Viśa' Chiye (尉遲遲耶) 829

- Viśa' Nanta (尉遲南塔) 844

- Viśa' Wana (尉遲佤那) 859

- Viśa' Piqiluomo (尉遲毗訖羅摩) 888

- Viśa' Saṃbhava (尉遲僧烏波) 912

- Viśa' Śūra (尉遲蘇拉) 967

- Viśa' Dharma (尉達磨) 978

- Viśa' Sangrāma (尉遲僧伽羅摩) 986

- Viśa' Sagemayi (尉遲薩格瑪依) 999

البوذية

The kingdom was one of the major centres of Buddhism, and up until the 11th century, the vast majority of the population was Buddhist.[45] Initially, the people of the kingdom were not Buddhist, and Buddhism was said to have been adopted in the reign of Vijayasambhava in the first century BC, some 170 years after the founding of Khotan.[46] However, an account by the Han general Ban Chao suggested that the people of Khotan in 73 AD still appeared to practice Mazdeism or Shamanism.[47][48] His son Ban Yong who spent time in the Western Regions also did not mention Buddhism there, and with the absence of Buddhist art in the region before the beginning of Eastern Han, it has also been suggested that Buddhism may not have been adopted in the region until the middle of the second century AD.[48]

The kingdom is primarily associated with the Mahayana.[49][50] According to the Chinese pilgrim Faxian who passed through Khotan in the fourth century:

The country is prosperous and the people are numerous; without exception they have faith in the Dharma and they entertain one another with religious music. The community of monks numbers several tens of thousands and they belong mostly to the Mahayana.[web 3]

It differed in this respect to Kucha, a Hinayana dominated kingdom on the opposite side of the desert where most of the wall paintings found in rock-cut viharas (monasteries) are connected with the Hinayana, though occasionally themes belonging to the Mahayana also appear.[51]

Faxian's account of the city states it had fourteen large and many small viharas.[52] Many foreign languages, including Chinese, Sanskrit, Prakrits, Apabhraṃśas and Classical Tibetan were used in cultural exchange. A number of Buddhist monks who played an important role in the transmission of Buddhism in China had their origins in Khotan including Śikṣānanda and Śīladharma.[53][54]

The most famous Buddhist manuscript from Khotan that is still preserved is the Book of Zambasta. Unlike the rest of the Buddhist texts that were written in the Old Khotanese, Book of Zambasta is the only original piece of literature as all the other documents were just translations from the Sanskrit. Book itself is an anthology that explores different themes of Buddhism throughout the text. It was named after the official who ordered it - Ysamasta (sound "ys" is the closest to the English letter "z").[55]

الحياة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية

Despite scant information on the socio-political structures of Khotan, the shared geography of the Tarim city-states and similarities in archaeological findings throughout the Tarim Basin enable some conclusions on Khotanese life.[56] A seventh-century Chinese pilgrim named Xuanzang described Khotan as having limited arable land but apparently particularly fertile, able to support "cereals and producing an abundance of fruits".[57] He further commented that the city "manufactures carpets and fine-felts and silks" as well as "dark and white jade". The city's economy was chiefly based upon water from oases for irrigation and the manufacture of traded goods.[58]

Xuanzang also praised the culture of Khotan, commenting that its people "love to study literature", and said "[m]usic is much practiced in the country, and men love song and dance." The "urbanity" of the Khotan people is also mentioned in their dress, that of 'light silks and white clothes' as opposed to more rural "wools and furs".[57]

الحرير

Khotan was the first place outside of inland China to begin cultivating silk. The legend, repeated in many sources, and illustrated in murals discovered by archaeologists, is that a Chinese princess brought silkworm eggs hidden in her hair when she was sent to marry the Khotanese king. This probably took place in the first half of the 1st century AD but is disputed by a number of scholars.[59]

One version of the story is told by the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang who describes the covert transfer of silkworms to Khotan by a Chinese princess. Xuanzang, on his return from India between 640 and 645, crossed Central Asia passing through the kingdoms of Kashgar and Khotan (Yutian in Chinese).[60]

اليشم

Khotan, throughout and before the Silk Roads period, was a prominent trading oasis on the southern route of the Tarim Basin – the only major oasis "on the sole water course to cross the desert from the south".[61] Aside from the geographical location of the towns of Khotan it was also important for its wide renown as a significant source of nephrite jade for export to China.

عملات خوتان

The Kingdom of Khotan is known to have produced both cash-style coinage and coins without holes[62][63][64]

| Inscription | Traditional Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Approximate years of production | King | Illustration (from A. Stein) |

Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu Fang | 于方 | yú fāng | 129–130 | Fang Qian | ||

| Zhong Er Shi Si Zhu Tong Qian | 重廿四銖銅錢 | CE100-200 | Maharajasa Yidirajasa Gurgamoasa | |||

| Liu Zhu | 六銖 | CE00-200 | Maharajasa Yidirajasa Gurgamoasa(?) |

تحليل دنا المتقدرة

At the cemetery in Sampul (Chinese: 山普拉), ~14 km from the archaeological site of Khotan in Lop County,[65] where Hellenistic art such as the Sampul tapestry has been found (its provenance most likely from the nearby Greco-Bactrian Kingdom),[66] the local inhabitants buried their dead there from roughly 217 BC to 283 AD.[67] Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the human remains has revealed genetic affinities to peoples from the Caucasus, specifically a maternal lineage linked to Ossetians and Iranians, as well as an Eastern-Mediterranean paternal lineage.[65][68] Seeming to confirm this link, from historical accounts it is known that Alexander the Great, who married a Sogdian woman from Bactria named Roxana,[69][70][71] encouraged his soldiers and generals to marry local women; consequentially the later kings of the Seleucid Empire and Greco-Bactrian Kingdom had a mixed Persian-Greek ethnic background.[72][73][74][75]

انظر أيضاً

- Khatana

- خوتان

- Rawak Stupa

- Dandan Oilik

- يوىژي

- انتشار البوذية على طريق الحرير

- مومياوات تريم

- Kamsabhoga

ملاحظات

الهامش

الكتب المرجعية

- ^ Stein, M. Aurel (1907). Ancient Khotan. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Charles Higham (2004). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Facts on File. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000), The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 77–81

- ^ أ ب H.W. Bailey (31 October 1979). Khotanese Texts (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-04080-8.

- ^ "神秘消失的古国(十):于阗". 华夏地理互动社区. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (16 October 2011). "City-states Along the Silk Road". ChinaKnowledge.de. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ "藏文文献中"李域"(li-yul,于阗)的不同称谓". qkzz.net. Archived from the original on 29 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Mukerjee 1964.

- ^ Jan Romgard (2008). "Questions of Ancient Human Settlements in Xinjiang and the Early Silk Road Trade, with an Overview of the Silk Road Research Institutions and Scholars in Beijing, Gansu, and Xinjiang" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (185): 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2012.

- ^ Jeong Su-il (17 July 2016). "Jade". The Silk Road Encyclopedia. Seoul Selection. ISBN 9781624120763.

- ^ أ ب Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. p. 263. ISBN 978-0521200929.

- ^ Smith, Vincent A. (1999). The Early History of India. Atlantic Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 978-8171566181.

- ^ Rhie, Marylin Martin (2007), Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, Volume 1 Later Han, Three Kingdoms and Western Chin in China and Bactria to Shan-shan in Central Asia, Leiden: Brill. p. 254.

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9781400829941.

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (28 March 1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0691024691.

- ^ أ ب ت James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 171.

- ^ Valerie Hansen (17 July 2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ^ George Michell; John Gollings; Marika Vicziany; Yen Hu Tsui (2008). Kashgar: Oasis City on China's Old Silk Road. Frances Lincoln. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-0-7112-2913-6.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. pp. 457–. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- ^ E. Yarshater, ed. (1983-04-14). "Chapter 7, The Iranian Settlements to the East of the Pamirs". The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0521200929.

- ^ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012. 71 (3): 632. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629.

- ^ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012. 71 (3): 633. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629.

- ^ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012. 71 (3): 634. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629.

- ^ Matthew Tom Kapstein; Brandon Dotson, eds. (20 July 2007). Contributions to the Cultural History of Early Tibet. Brill. p. 96. ISBN 978-9004160644.

- ^ أ ب Valerie Hansen (17 July 2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ^ Takao Moriyasu (2004). Die Geschichte des uigurischen Manichäismus an der Seidenstrasse: Forschungen zu manichäischen Quellen und ihrem geschichtlichen Hintergrund. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05068-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), p 207 - ^ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), p. 160 - ^ Johan Elverskog (6 June 2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8122-0531-2.

- ^ Anna Akasoy; Charles S. F. Burnett; Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (2011). Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-7546-6956-2.

- ^ Dankoff, Robert (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), p. 35 - ^ http://journals.manas.edu.kg/mjtc/oldarchives/2004/17_781-2049-1-PB.pdf

- ^ Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- ^ Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity In. Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- ^ J.M. Dent (1908), "Chapter 33: Of the City of Khotan - Which is Supplied with All the Necessaries of Life", The travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, pp. 96–97

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. p. 18. ISBN 9780520243408.

- ^ Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1974). Comprehensive history of Bihar. Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute.

- ^ Emmerick, R E (1979). A guide to the literature of Khotan. Reiyukai Library., p.4-5.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 17.

- ^ Legge, James. Trans. and ed. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: being an account by the Chinese monk Fâ-hsien of his travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1965, pp. 16-20.

- ^ Hill (1988), p. 184.

- ^ Hill (1988), p. 185.

- ^ Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols., p. 180. Clarendon Press. Oxford. [1]

- ^ Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols., p. 183. Clarendon Press. Oxford. [2]

- ^ Ehsan Yar-Shater, William Bayne Fisher, The Cambridge history of Iran: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press, 1983, page 963.

- ^ Baij Nath Puri (December 1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 53. ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5.

- ^ Xavier Tremblay (2007-05-11). Ann Heirman; Stephan Peter Bumbacher (eds.). The Spread of Buddhism. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15830-6.

- ^ أ ب Ma Yong; Sun Yutang (1999). Janos Harmatta (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilisations: Vol 2. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-81-208-1408-0.

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. London. p. 95.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). "Khotan", in Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia. UNESCO. 2006. p. 292. ISBN 978-9231032110.

- ^ "Travels of Fa-Hsien – Buddhist Pilgrim of Fifth Century By Irma Marx". Silkroads foundation. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ Ruixuan, Chen. "Buddhism in Khotan". Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism Online. doi:10.1163/2467-9666_enbo_COM_4206.

- ^ Lopez, Donald (2014). "Śikṣānanda". The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^

Guang-Dah, Z. (1996). B. A. Litvinsky (ed.). The City-States of the Tarim Basin (History of Civilisations of Central Asia: Vol III, The Crossroads of Civilisations: A.D.250-750 ed.). Paris. p. 284.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب

Hsüan-Tsang (1985). "Chapter 12". In Ji Xianlin (ed.). Records of the Western Regions. Peking.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Guang-dah, Z. The City-States of the Tarim Basin. p. 285.

- ^ Hill (2009). "Appendix A: Introduction of Silk Cultivation to Khotan in the 1st Century CE", pp. 466-467.

- ^ Boulnois, L (2004). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors and Merchants on the Silk Road. Odyssey. pp. 179.

- ^

Whitfield, Susan (1999). Life Along the Silk Road. London. p. 24.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Khotan lead coin". Vladimir Belyaev (Chinese Coinage Web Site). (in الإنجليزية). 3 December 1999. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ "Ancient Khotan" (PDF). by Stein Márk Aurél (hosted on Wikimedia Commons). (in الإنجليزية). 1907. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Cribb, Joe, "The Sino-Kharosthi Coins of Khotan: Their Attribution and Relevance to Kushan Chronology: Part 1", Numismatic Chronicle Vol. 144 (1984), pp. 128–152; and Cribb, Joe, "The Sino-Kharosthi Coins of Khotan: Their Attribution and Relevance to Kushan Chronology: Part 2", Numismatic Chronicle Vol. 145 (1985), pp. 136–149.

- ^ أ ب Chengzhi, Xie; Chunxiang, Li; Yinqiu, Cui; Dawei, Cai; Haijing, Wang; Hong, Zhu; Hui, Zhou (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of ancient Sampula population in Xinjiang". Progress in Natural Science. 17 (8): 927–933. doi:10.1080/10002007088537493.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp 15-16, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27 & footnote #46, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Livius.org. "Roxane." Articles on Ancient History. Page last modified 17 August 2015. Retrieved on 8 September 2016.

- ^ Strachan, Edward and Roy Bolton (2008), Russia and Europe in the Nineteenth Century, London: Sphinx Fine Art, p. 87, ISBN 978-1-907200-02-1.

- ^ For another publication calling her "Sogdian", see Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 4, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Holt, Frank L. (1989), Alexander the Great and Bactria: the Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia, Leiden, New York, Copenhagen, Cologne: E. J. Brill, pp 67–8, ISBN 90-04-08612-9.

- ^ Ahmed, S. Z. (2004), Chaghatai: the Fabulous Cities and People of the Silk Road, West Conshokoken: Infinity Publishing, p. 61.

- ^ Magill, Frank N. et al. (1998), The Ancient World: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 1, Pasadena, Chicago, London,: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, Salem Press, p. 1010, ISBN 0-89356-313-7.

- ^ Lucas Christopoulos writes the following: "The kings (or soldiers) of the Sampul cemetery came from various origins, composing as they did a homogenous army made of Hellenized Persians, western Scythians, or Sacae Iranians from their mother’s side, just as were most of the second generation of Greeks colonists living in the Seleucid Empire. Most of the soldiers of Alexander the Great who stayed in Persia, India and central Asia had married local women, thus their leading generals were mostly Greeks from their father’s side or had Greco-Macedonian grandfathers. Antiochos had a Persian mother, and all the later Indo-Greeks or Greco-Bactrians were revered in the population as locals, as they used both Greek and Bactrian scripts on their coins and worshipped the local gods. The DNA testing of the Sampul cemetery shows that the occupants had paternal origins in the eastern part of the Mediterranean"; see Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27 & footnote #46, ISSN 2157-9687.

مراجع الوب

- ^ "Archaeological GIS and Oasis Geography in the Tarim Basin". The Silk Road Foundation Newsletter. Archived from the original on 27 سبتمبر 2007. Retrieved 21 يوليو 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Sakan Language". The Linguist. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ أ ب بوذية خوتان

المصادر

- Histoire de la ville de Khotan: tirée des annales de la chine et traduite du chinois ; Suivie de Recherches sur la substance minérale appelée par les Chinois PIERRE DE IU, et sur le Jaspe des anciens. Abel Rémusat. Paris. L’imprimerie de doublet. 1820. Downloadable from: [3]

- Bailey, H. W. (1961). Indo-Scythian Studies being Khotanese Texts. Volume IV. Translated and edited by H. W. Bailey. Indo-Scythian Studies, Cambridge, The University Press. 1961.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2.

- Beal, Samuel. 1884. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. 2 vols. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969.

- Beal, Samuel. 1911. The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang by the Shaman Hwui Li, with an Introduction containing an account of the Works of I-Tsing. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. 1911. Reprint: Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. 1973.

- Emmerick, R. E. 1967. Tibetan Texts Concerning Khotan. Oxford University Press, London.

- Emmerick, R. E. 1979. Guide to the Literature of Khotan. Reiyukai Library, Tokyo.

- Grousset, Rene. 1970. The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Trans. by Naomi Walford. New Brunswick, New Jersey. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9

- Hill, John E. July, 1988. "Notes on the Dating of Khotanese History." Indo-Iranian Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3. See: [4] for paid copy of original version. Updated version of this article is available for free download (with registration) at: [5]

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation. [6]

- Hill, John E. (2009), Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE, Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge, ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1

- Legge, James. Trans. and ed. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: being an account by the Chinese monk Fâ-hsien of his travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1965.

- Mukerjee, Radhakamal (1964), The flowering of Indian art: the growth and spread of a civilization, Asia Pub. House

- Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1974), Comprehensive history of Bihar, Volume 1, Deel 2, Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute

- Sims-Williams, Ursula. 'The Kingdom of Khotan to AD 1000: A Meeting of Cultres.' Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology 3 (2008).

- Watters, Thomas (1904–1905). On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India. London. Royal Asiatic Society. Reprint: 1973.

- Whitfield, Susan. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. London. The British Library 2004.

- Williams, Joanna. 'Iconography of Khotanese Painting'. East & West (Rome) XXIII (1973), 109-54.

- R. E. Emmerick. 'Tibetan texts concerning Khotan'. London, New York [etc.] Oxford U.P. 1967.

للاستزادة

- Hill, John E. (2003). Draft version of: "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. 2nd Edition." "Appendix A: The Introduction of Silk Cultivation to Khotan in the 1st Century CE." [7]

- Martini, G. (2011). "Mahāmaitrī in a Mahāyāna Sūtra in Khotanese - Continuity and Innovation in Buddhist Meditation", Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal 24: 121-194. ISSN 1017-7132. [8]

- 1904 Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan, London, Hurst and Blackett, Ltd. Reprint Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras, 2000 Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan : vol.1

- 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford.[1] Ancient Khotan : vol.1 Ancient Khotan : vol.2

وصلات خارجية

- THE SPREAD OF INDIAN ART AND CULTURE TO CENTRAL ASIA AND CHINA

- ZENO coins page on Khotan

- Discussion on Sulekha.com[dead link]

- Smallest ancient temple discovered

- ^ M. A. Stein – Digital Archive of Toyo Bunko Rare Books at dsr.nii.ac.jp

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة التبتية

- Articles with dead external links from December 2017

- تاريخ شينجيانگ

- انحلالات 1006 في آسيا

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في عقد 50

- امبراطوريات إيرانية

- مواقع على طريق الحرير

- ممالك بوذية في آسيا الوسطى

- دافعو الجزية للصين الامبراطورية