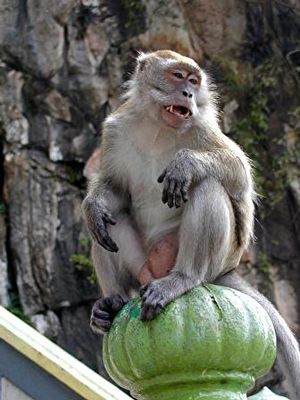

المكاك آكل الكابوريا

| المكاك آكل الكابوريا | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ngarai Sianok, Bukittinggi, West Sumatra | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | الحياة |

| مملكة: | الحيوانية |

| Phylum: | حبليات |

| Class: | الثدييات |

| تحت رتبة: | جافة الأنف |

| فوق رتبة: | القرديات |

| جنس: | المكاك |

| Species: | M. fascicularis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Macaca fascicularis Raffles, 1821

| |

| |

| Crab-eating macaque range | |

| Synonyms[2][3][4][5] | |

مكاك طويل الذيل أو مكاك الآكل للكابوريا (الاسم العلمي:Macaca fascicularis) إنگليزية: crab-eating macaque هو نوع من الحيوانات يتبع جنس السعدان المكاك من فصيلة قردة العالم القديم[6] [7] .

التبويب

The 10 subspecies of M. fascicularis are:

- Common long-tailed macaque, M. f. fascicularis

- Burmese long-tailed macaque, M. f. aurea

- Nicobar long-tailed macaque, M. f. umbrosa

- Dark-crowned long-tailed macaque, M. f. atriceps

- Con Song long-tailed macaque, M. f. condorensis

- Simeulue long-tailed macaque, M. f. fusca

- Lasia long-tailed macaque, M. f. lasiae

- Maratua long-tailed macaque, M. f. tua

- Kemujan long-tailed macaque, M. f. karimondjawae

- Philippine long-tailed macaque, M. f. philippensis [8]

Behavior

Group living

Macaques live in social groups that contain three to 20 females, their offspring, and one or many males. The groups usually have fewer males than females. In social groups of macaques, a clear dominance hierarchy is seen among females. These ranks remain stable throughout the female’s lifetime and also can be sustained through generations of matrilines. Females have their highest birth rates around 10 years of age and completely stop bearing young by age 24.[9]

The social groups of macaques are female-bonded, meaning the males will disperse at the time of puberty. Thus, group relatedness on average appears to be lower than compared to matrilines. More difference in relatedness occurs when comparing high-ranking lineages to lower ranking lineages, with higher-ranking individuals being more closely related to one another. Additionally, groups of dispersing males born into the same social groups display a range of relatedness, at times appearing to be brothers, while at other times appearing to be unrelated.[10]

In addition to the matrilineal dominance hierarchy, male dominance rankings also exist. Alpha males have a higher frequency of mating compared to their lower-ranking conspecifics. The increased success is due partially to his increased access to females and also due to female preference of an alpha male during periods of maximum fertility. Though females have a preference for alpha males, they do display promiscuous behavior. Through this behavior, females risk helping to rear a nonalpha offspring, yet benefit in two specific ways, both in regard to aggressive behavior. First, a decreased value is placed on one single copulation. Moreover, the risk of infanticide is decreased due to the uncertainty of paternity.[11]

Increasing group size leads to increased competition and energy spent trying to forage for resources, and in particular, food. Further, social tensions build and the prevalence of tension-reducing interactions like social grooming fall with larger groups. Thus, group living appears to be maintained solely due to the safety against predation.[12]

Conflict

Group living in all species is dependent on tolerance of other group members. In crab-eating macaques, successful social group living maintains postconflict resolution must occur. Usually, less dominant individuals lose to a higher-ranking individual when conflict arises. After the conflict has taken place, lower-ranking individuals tend to fear the winner of the conflict to a greater degree. In one study, this was seen by the ability to drink water together. Postconflict observations showed a staggered time between when the dominant individual begins to drink and the subordinate. Long-term studies reveal the gap in drinking time closes as the conflict moves further into the past.[13]

Grooming and support in conflict among primates is considered to be an act of reciprocal altruism. In crab-eating macaques, an experiment was performed in which individuals were given the opportunity to groom one another under three conditions: after being groomed by the other, after grooming the other, and without prior grooming. After a grooming took place, the individual that received the grooming was much more likely to support its groomer than one that had not previously groomed that individual. These results support the reciprocal altruism theory of grooming in long-tailed macaques.[14]

Crab-eating macaques demonstrate two of the three forms of suggested postconflict behavior. In both captive and wild studies, the monkeys demonstrated reconciliation, or an affiliative interaction between former opponents, and redirection, or acting aggressively towards a third individual. Consolation was not seen in any study performed.[15]

Postconflict anxiety has been reported in crab-eating macaques that have acted as the aggressor. After a conflict within a group, the aggressor appears to scratch itself at a higher rate than before the conflict. Though the scratching behavior cannot definitely be termed as an anxious behavior, evidence suggests this is the case. An aggressor’s scratching decreases significantly after reconciliation. This suggests reconciliation rather than a property of the conflict is the cause of reduction in scratching behavior. Though these results seem counterintuitive, the anxiety of the aggressor appears to have a basis in the risks of ruining cooperative relationships with the opponent.[16]

Kin altruism and spite

In a study, a group of crab-eating macaques was given ownership of a food object. Unsurprisingly, adult females favored their own offspring by passively, yet preferentially, allowing them to feed on the objects they held. Interestingly, when juveniles were in possession of an object, mothers robbed them and acted aggressively at an increased rate towards their own offspring compared to other juveniles. These observations suggest close proximity influences behavior in ownership, as a mother’s kin are closer to her on average. When given a nonfood object and two owners, one being a kin and one not, the rival will choose the older individual to attack regardless of kinship. Though the hypothesis remains that mother-juvenile relationships may facilitate social learning of ownership, the combined results clearly point to aggression towards the least-threatening individual.[17]

A study was conducted in which food was given to 11 females. They were then given a choice to share the food with kin or nonkin. The kin altruism hypothesis suggests the mothers would preferentially give food to their own offspring. Yet eight of the 11 females did not discriminate between kin and nonkin. The remaining three did, in fact, give more food to their kin. The results suggest it was not kin selection, but instead spite that fueled feeding kin preferentially. This is due to the observation that food was given to kin for a significantly longer period of time than needed. The benefit to the mother is decreased due to less food availability for herself and the cost remains great for nonkin due to not receiving food. If these results are correct, crab-eating macaques are unique in the animal kingdom, as they appear not only to behave according to the kin selection theory, but also act spiteful toward one another.[18]

Reproduction

After a gestation period of 162–193 days, the female gives birth to one infant. The infant's weight at birth is about 320 g (11 oz).[19] Infants are born with black fur which will begin to turn to a yellow-green, grey-green, or reddish-brown shade (depending on the subspecies) after about three months of age.[20] This natal coat may indicate to others the status of the infant, and other group members treat infants with care and rush to their defense when distressed. Immigrant males sometimes kill infants not their own, and high-ranking females sometimes kidnap the infants of lower-ranking females. These kidnappings usually result in the death of the infants, as the other female is usually not lactating. A young juvenile stays mainly with its mother and relatives. As male juveniles get older, they become more peripheral to the group. Here they play together, forming crucial bonds that may help them when they leave their natal group. Males that emigrate with a partner are more successful than those that leave alone. Young females, though, stay with the group and become incorporated into the matriline into which they were born.[21]

Male crab-eating macaques groom females to increase the chance of mating. A female is more likely to engage in sexual activity with a male that has recently groomed her than with one that has not.[22]

Diet

Despite their name, crab-eating macaques typically do not consume crabs as their main food source; rather, they are opportunistic omnivores, eating a variety of animals and plants. Although fruits and seeds make up 60 - 90% of their diet, they also eat leaves, flowers, roots, and bark.[19] They sometimes prey on vertebrates (including bird chicks, nesting female birds, lizards, frogs, and fish), invertebrates, and bird eggs. In Indonesia, the species has become a proficient swimmer and diver for crabs and other crustaceans in mangrove swamps.[23] A study in Bukit Timah, Singapore recorded a diet consisting of 44% fruit, 27% animal matter, 15% flowers and other plant matter, and 14% food provided by humans.[24]

This species exhibits particularly low tolerance for swallowing seeds. Despite their inability to digest seeds, many primates of similar size swallow large seeds, up to 25 mm (0.98 in), and simply defecate them whole. The crab-eating macaque, though, spits seeds out if they are larger than 3–4 mm (0.12–0.16 in). This decision to spit seeds is thought to be adaptive; it avoids filling the monkey’s stomach with wasteful bulky seeds that cannot be used for energy.[25] It also can help the plants by distributing seeds to new areas: Crab-eating macaques eat durians such as Durio graveolens and D. zibethinus, and are a major seed disperor for the latter species.[26]

Although the species is ecologically well-adapted and poses no threat to population stability of prey species in its native range, in areas where the crab-eating macaque is not native, it can pose a substantial threat to biodiversity.[27] Some believe the crab-eating macaque is responsible for the extinction of forest birds by threatening critical breeding areas [28] as well as eating the eggs and chicks of endangered forest birds.[29]

The crab-eating macaque can become a synanthrope, living off human resources. They are known to feed in cultivated fields on young dry rice, cassava leaves, rubber fruit, taro plants, coconuts, mangos, and other crops, often causing significant losses to local farmers.[30] In villages, towns, and cities, they frequently take food from garbage cans and refuse piles.[30] The species can become unafraid of humans in these conditions, which can lead to macaques directly taking food from people, both passively and aggressively.

Tool use

In Thailand and Myanmar, crab-eating macaques use stone tools to open nuts, oysters, and other bivalves, and various types of sea snails (nerites, muricids, trochids, etc.) along the Andaman sea coast and offshore islands.[31]

Another instance of tool use is washing and rubbing foods such as sweet potatoes, cassava roots, and papaya leaves before consumption. Crab-eating macaques either soak these foods in water or rub them through their hands as if to clean them. They also peel the sweet potatoes, using their incisors and canine teeth. Adolescents appear to acquire these behaviors by observational learning of older individuals.[32]

Distribution and habitat

The crab-eating macaque lives in a wide variety of habitats, including primary lowland rainforests, disturbed and secondary rainforests, shrubland, and riverine and coastal forests of nipa palm and mangrove. They also easily adjust to human settlements; they are considered sacred at some Hindu temples and on some small islands,[33] but are pests around farms and villages. Typically, they prefer disturbed habitats and forest periphery. The native range of this species includes most of mainland Southeast Asia, from extreme southeastern Bangladesh south through Malaysia, and the Maritime Southeast Asia islands of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo, offshore islands, the islands of the Philippines, and the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. This primate is a rare example of a terrestrial mammal that violates the Wallace line.[29]

Introduced range

M. fascicularis is an introduced alien species in several locations, including Hong Kong, Taiwan, Irian Jaya, Papua New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland, New Caledonia, Solomon Islands, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Nauru, Vanuatu, Pohnpei, Anggaur Island in Palau, and Mauritius.[34] Where it is not a native species, particularly on island ecosystems whose species often evolved in isolation from large predators, M. fascicularis is a documented threat to many native species.[29] This has led the World Conservation Union (IUCN) to list M. fascicularis as one of the "100 worst invasive alien species".[35] M. fascicularis is not a threat to biodiversity in its native range.

The immunovaccine porcine zona pellucida (PZP), which causes infertility in females, is currently being tested in Hong Kong to investigate its use as potential population control.[29]

العلاقة بالبشر

وضع الحفاظ

الجينوم

| NCBI genome ID | 776 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | diploid |

| حجم الجينوم | 2,946.84 Mb |

| عدد الكروموسومات | 21 pairs |

جينوم المكاك آكل الكابوريا تم سـَلسلته.

Clones

On 24 January 2018, scientists in China reported in the journal Cell the creation of two crab-eating macaque clones, named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, using the complex DNA transfer method that produced Dolly the sheep.[36][37][38][39][40] This makes Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua the first primates to be cloned using the somatic cell nuclear transfer method.

انظر أيضاً

References

- ^ {{{assessors}}} (2008). Macaca fuscicularis. القائمة الحمراء للأنواع المهددة بالانقراض 2008. IUCN سنة 2008. تم استرجاعها في 4 January 2009.

- ^ P H Napier; C P Groves (July 1983). "Simia fascicularis Raffles, 1821 (Mammalia, Primates): request for the suppression under the plenary powers of Simia aygula Linnaeus, 1758, a senior synonym. Z.N.(S.) 2399". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 40 (2): 117–118. ISSN 0007-5167. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

Simia aygula is quite clearly the Crab-eating or Long-tailed Macaque, as Buffon opined as early as 1766.

- ^ J. D. D. Smith (2001). "Supplement 1986-2000" (PDF). Official List and Indexes of Names and Works in Zoology. International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. p. 8. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

Suppressed under the plenary power for the purposes of the Principle of Priority, but not for those of the Principle of Homonymy

- ^ Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). "Macaca fascicularis fascicularis". Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ. Regnum animale (10th ed.). p. 27. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ مصدر باللغة الإنكليزية - موقع تاكسونوميكون مكاك طويل الذيل تاريخ الولوج 21 أبريل 2013

- ^ مصدر باللغة الإنكليزية - موقع زيبكودزو مكاك طويل الذيل تاريخ الولوج 21 أبريل 2013

- ^ Wilson, Don E.; Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds. (2005). "Macaca fascicularis". Mammal species of the world : a taxonomic and geographic reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0.

- ^ van Noordwijk, Maria; Carcel van Schaik (January 1999). "The Effects of Dominance Rank and Group Size on Female Lifetime Reproductive Success in Wild Long-tailed Macaques, Macaca fascicularis". Primates. 40: 105–130. doi:10.1007/bf02557705.

- ^ de Ruiter, Jan; Eli Geffen (October 1998). "Relatedness of matrilines, dispersing males and social groups in long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 265 (1391): 79–87. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0267. PMC 1688868. PMID 9474793.

- ^ de Ruiter, Jan; Jan van Hooff; Wolfgang Scheffrahn (June 1995). "Social and Genetic Aspects of Paternity in Wild Long-Tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis)". Behaviour. 129 (3): 203–224. doi:10.1163/156853994x00613.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Schaik, Carel; Maria Noordwijk; Rob Boer; Isolde Tonkelaar (April 1983). "The effect of group size on time budgets and social behavior in wild long-tailed macaques". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 13 (3): 173–181. doi:10.1007/bf00299920.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Cords, Marina (December 1992). "Post-conflict reunions and reconciliation in long-tailed macaques". Animal Behaviour. 44: 57–61. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(05)80754-7.

- ^ Hemelrijk, Charlotte (February 1994). "Support for being groomed in long-tailed macaques, Macaca fascicularis". Animal Behaviour. 48 (2): 479–481. doi:10.1006/anbe.1994.1264.

- ^ Aureli, Filippo (June 1992). "Post-conflict behaviour among wild long-tailed macaques, (Macaca fascicularis)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 31 (5): 329–337. doi:10.1007/bf00177773.

- ^ Das, Marjolijn; Zsuzsa Penke; Jan van Hoof (1998). "Potconflict Affiliation and Stress-Related Behavior of Long-Tailed Macaque Aggressors". International Journal of Primatology. 19: 53–71. doi:10.1023/A:1020354826422.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Kummer, Hans; Marina Cords (December 1991). "Cues of ownership in long-tailed macaques, Macaca fascicularis". Animal Behaviour. 42 (4): 529–549. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(05)80238-6.

- ^ Schaub, Hanspeter (1996). "Testing Kin Altruism in Long-Tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in a Food-sharing Experiment". International Journal of Primatology. 17 (3): 445–467. doi:10.1007/bf02736631.

- ^ أ ب Bonadio, Christopher (2000). "Macaca fascicularis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPrimate Factsheets - ^ Cawthon Lang, Kristina. > "Primate Factsheets: Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) Behavior". Primate Info Net. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Gumert, Michael D. (December 2007). "Payment for sex in a macaque mating market". Animal Behaviour. 74 (6): 1655–1667. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.03.009.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-08-28. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Lucas, P.W. "Long-tailed Macaques". The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore Supplement No. 3 (PDF). Singapore Botanic Gardens: National Parks Board. pp. 107–112. ISSN 0374-7859. Retrieved 2015-08-14.

- ^ Corlett, R.T.; P.W. Lucas (1990). "Alternative Seed-Handling Strategies in Primates: Seed-Spitting by Long-Tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis)". Oecologia. 82 (2): 166–171. Bibcode:1990Oecol..82..166C. doi:10.1007/bf00323531. JSTOR 4219219. PMID 28312661.

- ^ Nakashima, Yoshihiro; Lagan, Peter; Kitayama, Kanehiro (March 2008). "A Study of Fruit–Frugivore Interactions in Two Species of Durian (Durio, Bombacaceae) in Sabah, Malaysia" (PDF). Biotropica (in English). John Wiley & Sons. 40 (2): 255–258. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00335.x. ISSN 1744-7429. OCLC 5155811169. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Richer, Nathan. "Wild Facts". Wild Fact #834 – The Perfect Gift – Crab-Eating Macaque. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Hazan, Tracy. "Introduced Species Summary Project". Crab-eating Macaque (Macaca fascicularis). Columbia University. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ أ ب ت ث Carter, Steve. "Global Invasive Species Database". Macaca fascicularis (mammal). Invasive Species Specialist Group. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ أ ب Long, John (2003). Introduced Mammals of the World: Their History, Distribution, and Influence. Australia: CSIRO Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 0643067140.

- ^ Gumert, MD; Kluck, M.; Malaivijitnond, S. (2009). "The physical characteristics and usage patterns of stone axe and pounding hammers used by long-tailed macaques in the Andaman Sea region of Thailand". American Journal of Primatology. 71 (7): 594–608. doi:10.1002/ajp.20694. PMID 19405083.

- ^ Wheatley, Bruce (June 1988). "Cultural behavior and extractive foraging in Macaca Fascicularis". Current Anthropology. 29 (3): 516–519. doi:10.1086/203670. JSTOR 2743474.

- ^ "Island of the Monkey God". Off the Fence. Archived from the original on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Long, J. L. (2003). Introduced Mammals of the World: Their History, Distribution and Influence. Csiro Publishing, Collingwood, Australia. ISBN 9780643099166

- ^ Lowe, S. "100 Of The World's Worst Invasive Species" (PDF). Invasive Species Specialist Group. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Liu, Zhen; et al. (24 January 2018). "Cloning of Macaque Monkeys by Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer". Cell. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.020. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Normile, Dennis (24 January 2018). "These monkey twins are the first primate clones made by the method that developed Dolly". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aa1066. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Cyranoski, David (24 January 2018). "First monkeys cloned with technique that made Dolly the sheep - Chinese scientists create cloned primates that could revolutionize studies of human disease". Nature. 553: 387–388. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (24 January 2018). "First monkey clones created in Chinese laboratory". BBC News. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Associated Press (24 January 2018). "Scientists Successfully Clone Monkeys; Are Humans Up Next?". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

External links

- Bonadio, C. 2000. "Macaca fascicularis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed March 10, 2006.

- Primate Info Net Macaca fascicularis Factsheet

- ISSG Database: Ecology of Macaca fascicularis

- Primate Info Net: Macaca fascicularis

- BBC Factfile on M. fascicularis

- "Conditions at Nafovanny", video produced by the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection following an undercover investigation at a captive-breeding facility for long-tailed macaques in Vietnam.

- قالب:UCSC genomes

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- CS1 errors: markup

- أنواع القائمة الحمراء غير المهددة

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Macaca

- Primates of Southeast Asia

- Mammals of Oceania

- Tool-using mammals

- Mammals of Bangladesh

- Mammals of Borneo

- Mammals of Brunei

- Mammals of Myanmar

- Mammals of Cambodia

- Mammals of East Timor

- Mammals of Indonesia

- Mammals of Laos

- Mammals of Malaysia

- Mammals of the Philippines

- Mammals of Singapore

- Mammals of Thailand

- Mammals of Vietnam

- Mammals of Fiji

- Mammals of Samoa

- Mammals of Tonga

- Invasive mammal species

- Space-flown life

- Mammals described in 1821

- Taxa named by Thomas Stamford Raffles

- حيوانات وصفت في 1821

- سعادين القردوح

- ثدييات إندونيسيا

- ثدييات ماليزيا

- حيوانات أوراسيا الضخمة

- سعدان المكاك

- غينوناوات

- رباحاوية

- قردة العالم القديم

- أنواع الثدييات

- أنواع حيوانية