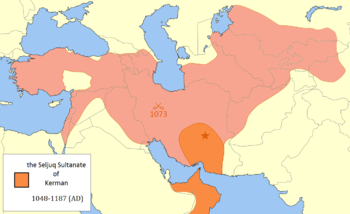

سلاجقة كرمان

Kerman Seljuk Sultanate قاوٙرْدیان یا آل قاوٙرد | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1041 (429 AH)–1187 (552 AH) | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| الوضع | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| العاصمة | Kerman | ||||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | Persian | ||||||||||

| الدين | Islam, Sunni | ||||||||||

| الحكومة | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• تأسست | 1041 (429 AH) | ||||||||||

• War with Great Seljuks (Kerj abudulaf) | 465 AH | ||||||||||

• Murdered of Iranshah of Kerman | 495 | ||||||||||

• Civil Wars | 562-572 | ||||||||||

• invasion of Ghuzz | 575 AH | ||||||||||

• انحلت | 1187 (552 AH) | ||||||||||

| المساحة | |||||||||||

| 465 AH | 433،389 km2 (167،332 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 583 AH | 106،196 km2 (41،003 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| اليوم جزء من | |||||||||||

The Kerman Seljuk Sultanate (also known as Kerman sultanate Persian: سلجوقیان کرمان Saljūqiyān-i Kerman) was a Turko-Persian Sunni Muslim state, established in the parts of Kerman and Makran which had been conquered from the Buyid dynasty by the Seljuk Empire which was established by Seljuk Turks. The Founder of this dynasty, Emadeddin Kara Arslan Ahmad Qavurt who succeeded the ruler of this dynasty after the surrender of the ruler of Buyyids, Abu Kalijar Marzuban.[1] For first time in this period, an independent state was formed in Kerman; eventually, after 150 years, with the invasion of the Ghuz leader's Malik Dinar, the Kerman Seljuk Sultanate fall.

The government is the first powerful local government in the Kerman and Makran region, which, in addition to political and security stability, could create economic prosperity in the provinces. It was during this period that the Spice Road burgeoned with the flourishing of the ports of Tiz, Hormuz and Kish, and this state, as the highway of this important economic road, could use tremendous wealth with the conditions it had created. Regarding the scientific and social conditions, at this time, with the efforts of the Shahs such as Mohammad Shah II, the scientific and cultural centers were established in Kerman, and with these actions, Kerman, which was away from the main scientific centers, became the center of science in the southeastern region of Iran's plateau. In addition, Kerman and Makran under ruling of Seljuk, grew in agriculture and Animal husbandry, and Progressed in Commerce and trade which led to improved economic and social conditions.

Early history of Seljuq dynasty

The Seljuqs originated from the Qynyk branch of the Oghuz Turks,[2][3][4][5][6] who in the 9th century lived on the periphery of the Muslim world, north of the Caspian Sea and Aral Sea in their Yabghu Khaganate of the Oghuz confederacy,[7] in the Kazakh Steppe of Turkestan.[8] During the 10th century, due to various events, the Oghuz had come into close contact with Muslim cities.[9]

When Seljuq, the leader of the Seljuq clan, had a falling out with Yabghu, the supreme chieftain of the Oghuz, he split his clan off from the bulk of the Tokuz-Oghuz and set up camp on the west bank of the lower Syr Darya. Around 985, Seljuq converted to Islam.[9] In the 11th century the Seljuqs migrated from their ancestral homelands into mainland Persia, in the province of Khurasan, where they encountered the Ghaznavid empire. In 1025, 40,000 families of Oghuz Turks migrated to the area of Caucasian Albania.[10] The Seljuqs defeated the Ghaznavids at the Battle of Nasa plains in 1035. Tughril, Chaghri, and Yabghu received the insignias of governor, grants of land, and were given the title of dehqan.[11] At the Battle of Dandanaqan they defeated a Ghaznavid army, and after a successful siege of Isfahan by Tughril in 1050/51,[12] they established an empire later called the Great Seljuk Empire. The Seljuqs mixed with the local population and adopted the Persian culture and Persian language in the following decades.[13][14][15][16][17]

Alp Arslan's will

Alp Arslan died in 1072. But before death he willed his throne to Malik Shah I, his second son. He also expressed his concern about possible throne struggles. The main contestants for the throne were his eldest son Ayaz and his brother Qavurt. As a compromise, he willed generous grants to Ayaz and Qavurt. He also willed Qavurt to marry his widow.

Qavurt's rebellion

Malik Shah was only 17 or 18 years of age when he ascended to throne. Although Ayaz presented no problem, he faced with the serious problem of Qavurt's rebellion.[18] His vizier Nizam al-Mulk was even more worried for he had become the de facto ruler of the empire during young Malik Shah's reign. Although Qavurt had only a small army, Turkmen officiers in Malik Shah's army tended to support Qavurt. So Malik Shah and Nizam al-Mulk added non Turkic regiments to Seljuk army. Artukids also supported Malik Shah. The clash was at a location known as Kerç kapı (or Kerec [19] ) close to Hamedan on 16 May 1073. Malik Shah was able to defeat Qavurt's forces. Although Qavurt escaped, he was soon arrested. Initially Malik Shah was tolerant to his uncle. But Nizam al-Mulk convinced the young sultan to execute Qavurt. Nizam al-Mulk also executed Qavurt's four sons.[20] Later he eliminated most of the Turkic commanders of the army whom he suspected to be Qavurt's partisan.

استعراض

The son of Bahram-Shah, Muhammad-Shah succeeded his uncle Turan-Shah to the throne of Kerman in 1183. By the time of his ascension Kerman had been overrun by bands of Ghuzz Turks. Their devastation of the province had made the city of Bardasir virtually uninhabitable, so Muhammad-Shah made Bam his capital. By 1186, however, Muhammad-Shah been unable to handle the Ghuzz, and he decided to abandon Bam and departed from Kerman. The Ghuzz chief Malik Dinar quickly seized control of Kerman in his place.[21]

Muhammad-Shah at first hoped to receive foreign assistance to reacquire Kerman, and traveled to Fars and Iraq requesting help. He also sought for aid from the Khwarezmshah Tekish. Eventually, however, he realized that he could get no assistance in recovering Kerman. He made his way to the Ghurid Empire and spent the remainder of his life in the service of the Ghurid sultans.[21] {

الحكام السلاجقة لكرمان

كانت كرمان محافظة في جنوب فارس. وبين عامي 1053 و 1154، ضمت المنطقة أيضاً عُمان.

- قاورد 1041–1073

- كرمان شاه 1073–1074

- سلطان شاه 1074–1075

- حسين عمر 1075–1084

- طوران شاه الأول 1084–1096

- إيران شاه 1096–1101

- أرسلان شاه الأول 1101–1142

- Mehmed I (Muhammad) 1142–1156

- Toğrül Shah 1156–1169

- Bahram Shah 1169–1174

- أرسلان شاه الثاني 1174–1176

- Turan Shah II 1176–1183

- Muhammad Shah 1183–1187

Muhammad abandoned Kerman, which fell into the hands of the Oghuz chief Malik Dinar. Kerman was eventually annexed by the Khwarezmid Empire in 1196. قالب:Kerman Seljuk Sultanate Family Tree

المراجع

- ^ Family tree of Seljuks[dead link]

- ^ Concise Britannica Online Seljuq Dynasty Archived 2007-01-14 at the Wayback Machine article

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online – Definition of Seljuk

- ^ The History of the Seljuq Turks: From the Jami Al-Tawarikh (LINK)

- ^ Shaw, Stanford. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (LINK)

- ^ Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic People. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. p. 209

- ^ Wink, Andre, Al Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8 pg.9

- ^ Islam: An Illustrated History, p. 51

- ^ أ ب Michael Adas, Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History, (Temple University Press, 2001), 99.

- ^ "The Caucasus & Globalization." Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies. Institute of Strategic Studies of the Caucasus. Volume 5, Issue 1-2. 2011, p.116. CA&CC Press. Sweden.

- ^ Bosworth, C.E. The Ghaznavids: 994-1040, Edinburgh University Press, 1963, 242.

- ^ Tony Jaques, Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O, (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007), 476.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةiranica - ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition, (LINK): "... Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship ..."

- ^ M. Ravandi, "The Seljuq court at Konya and the Persianisation of Anatolian Cities", in Mesogeios (Mediterranean Studies), vol. 25–6 (2005), pp. 157–69

- ^ M.A. Amir-Moezzi, "Shahrbanu", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK): "... here one might bear in mind that Turco-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Seljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkish heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- ^ F. Daftary, "Sectarian and National Movements in Iran, Khorasan, and Trasoxania during Umayyad and Early Abbasid Times", in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol 4, pt. 1; edited by M.S. Asimov and C.E. Bosworth; UNESCO Publishing, Institute of Ismaili Studies: "... Not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks (eleventh and twelfth centuries), the Timurids (fourteenth–fifteenth centuries), and the Qajars (nineteenth–twentieth centuries) ..."

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Expo 70 ed. Vol 14, p. 699

- ^ Sina Akşin-Ümit Hassan: Türkiye Tarihi 1 Vatan Kitap, 2009, ISBN 975-406-563-2, p.180

- ^ [1][dead link] Salim Koca: The Forces in the Determination of the Political Power in the Seljuk State (in تركية)

- ^ أ ب Bosworth, p. 174

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2006). Peoples of Western Asia. p. 364.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. p. 280.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Borrero, Mauricio (2009). Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. p. 162.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref=

- Bosworth, C. E. (2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: a Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2137-7.

- Grousset, Rene (1988). The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0813506271.

- Peacock, A.C.S., Early Seljuq History: A New Interpretation; New York, NY; Routledge; 2010

- Previté-Orton, C. W. (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Articles with dead external links from February 2020

- Articles with dead external links from July 2016

- Articles with تركية-language sources (tr)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Former country articles categorised by government type

- دول توركية تاريخية

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1048

- History of Kerman Province

- 1048 establishments in Asia