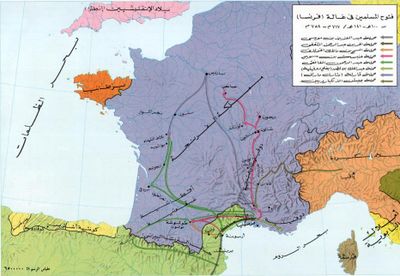

الفتح الإسلامي لبلاد الغال

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

الفتح الإسلامي لبلاد الغال جاء في أعقاب الفتح الإسلامي لهسپانيا بقيادة القائد الشمال أفريقي طارق بن زياد عام 711. في القرن الثامن فتحت الجيوش الأموية المسلمة منطقة سپتيمانيا، آخر معاقل مملكة القوط الغربيين.[1] Although the Umayyads secured control of Septimania, their incursions beyond this region into the Loire and Rhône valleys failed. In 759, Muslim forces lost Septimania to the Christian Frankish Empire and retreated to the Iberian Peninsula which they called al-Andalus.

The 719 Umayyad invasion of Gaul was the continuation of their conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania. Septimania, in southern Gaul, was the last unconquered province of the Visigothic Kingdom.[2] Muslim armies began to campaign in Septimania in 719. After the fall, in 720, of Narbonne, the capital of the Visigothic rump state, Umayyad armies composed of Arabs and Berbers turned north against Aquitaine. Their advance was stopped at the Battle of Toulouse in 721, but they sporadically raided the southern half of Gaul as far as Avignon and Lyon.[2]

A major Umayyad raid directed at Tours was defeated in the Battle of Tours in 732. After 732, the Franks asserted their authority in Aquitaine and Burgundy, but only in 759 did they manage to take the Mediterranean region of Septimania, due to Muslim neglect and local Visigothic disaffection.[2]

After the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate and the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in 750, internal conflicts within al-Andalus, including revolts and the establishment of the Emirate of Córdoba under Abd al-Rahman I, shifted the focus of Andalusi Muslim leaders towards internal consolidation. However, sporadic military expeditions were still launched into Gaul. Some of these raids resulted in temporary Muslim settlements in remote areas, but they were not integrated into the emirate's authority and soon vanished from historical records.

A Muslim incursion into Gaul in the ninth century resulted in the establishment of Fraxinetum, a fortress in Provence that lasted for nearly a century.

الفتح الإسلامي لسپتيمانيا

By 716, under the pressure of the Umayyad Caliphate from the south, the Kingdom of the Visigoths had been rapidly reduced to a rump state in the province of Narbonensis (Septimania), a region which corresponds approximately to the modern Languedoc-Roussillon. In 713 the Visigoths of Septimania elected Ardo as king. He ruled from Narbonne. In 717, the Umayyads under al-Hurr ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Thaqafi crossed the Pyrenees for the first time on a reconnaissance mission. The following campaign of conquest in Septimania lasted three years.[3][4] Late Muslims sources, such as Ahmad al-Maqqari, describe Musa ibn Nusayr (712–714) as leading an expedition to the Rhône at the far east of the Visigothic kingdom, but these are not reliable.[3]

The next Umayyad governor, al-Samh, crossed the Pyrenees in 719 and conquered Narbonne (Arbuna to the Arabs) in that year or the following (720).[3] According to the Chronicle of Moissac, the inhabitants of the city were slaughtered.[5] The fall of the city ended the seven-year reign of Ardo and with it the Visigothic kingdom, but Visigothic nobles continued to hold the Septimanian cities of Carcassonne and Nîmes.[3][4] Nevertheless, al-Samh established garrisons in Septimania in 721, intending to incorporate it permanently into the territories of al-Andalus.[4]

However, the Umayyad tide was temporarily halted by the large-scale Battle of Toulouse (721), when al-Samh (Zama in the Christian chronicles) was killed by Odo of Aquitaine. Despite the defeat at Toulouse, the Umayyads still controlled Narbonne and had a strong military presence in Septimania. The Umayyads were far from their core territory in Iberia and needed local support so they offered the local Gothic nobles favorable terms and some autonomy in exchange for tribute and recognition of Umayyad authority. The Visigothic resistance was fragmented and weakened after years of war and the loss of their king. For many Gothic nobles, the agreement was preferable to continued war or subjugation by the Franks or Aquitanians, who were also regional rivals. As a result, many of the Gothic nobles of the Visigothic rump state in Septimania aligned themselves with the Muslims.

In 725, al-Samh's successor, Anbasa ibn Suhaym al-Kalbi, moved against Gothic nobles resisting surrender. The city of Carcassonne was besieged and its Gothic ruler forced to cede half of his territory, pay tribute, and make an offensive and defensive alliance with Muslim forces. The Gothic rulers of Nîmes and the other resisting Septimanian cities also eventually fell under the sway of the Umayyads. In the 720s the savage fighting, the massacres and destruction particularly affecting the Ebro valley and Septimania unleashed a flow of refugees who mainly found shelter in southern Aquitaine across the Pyrenees, and Provence.[6]

Sometime during this period, the Berber commander Uthman ibn Naissa ("Munuza") became governor of the Cerdanya (also including a large swathe of present-day Catalonia). By that time, resentment against Arab rulers was growing within the Berber troops.

الإغارة على أكيتان وپواتو

ثورة عثمان بن النيسا

By 725, all of Septimania was under Umayyad rule. Uthman ibn Naissa, the Pyrenean Berber ruler of the eastern Pyrenees, detached himself from Cordova and established a principality based on a Berber power base in 731. The Berber leader allied with the Aquitanian duke Odo, who was eager to stabilize his borders, and is reported to have married Odo's daughter Lampegia. Uthman ibn Naissa went on to kill Nambaudus, the bishop of Urgell,[7] an official acting on the orders of the Church of Toledo.

The new Umayyad governor in Cordova, Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi, mustered an expedition to punish the Berber commander's insubordination, surrounding and putting him to death in Cerdanya, according to the Mozarabic Chronicle, a just retribution for killing the Gothic bishop.

التجريدة الأموية على أكيتان

حشد الغافقي جيشاً قوامه 50 ألف مقاتل،[8] وهو أكبر جيش أموي دخل الأندلس وغالية حتى ذلك الوقت[9]، فحتى طارق بن زياد كان جيشه يتألف من 7 آلاف مقاتل، وطريف بن مالك كان جيشه 5 آلاف، وموسى بن نصير كان جيشه 18 ألفاً، وبذلك يكون جيشهم جميعاً 30 ألف مقاتل[10]، أي أن الغافقي قد جهز حملة لم يسبق لأحد من قادة الأمويين قبله أن جهز مثلها.

كان الغافقي من طراز حسان بن النعمان يعمد إلى الفتح وترسيخه وتعزيز الحاميات قبل الانطلاق إلى فتحٍ غيره[11]، فانطلق في البداية من سرقسطة نحو إقليم كاتالونيا في الأندلس، وهو أقرب إقليم إلى بلاد الگال، فعمل على تقوية هذا الثغر والقضاء على الثوار فيه، ثم تحرك إلى إقليم سپتيمانيا الأموي فعزز من وجود الحاميات فيه، وعاد بعدها إلى مدينة بنبلونة في شمالي أيبيريا، فانطلق منها وعبر معبر الرونسفال في جبال المعابر أو جبال الأبواب (في اللاتينية تسمى جبال البرت، وتعني الباب)[12]، وكان هدفه أقطانيا (والتي كانت حدودها تنتهي عند نهر اللوار) والدوق أودو.

وصل الغافقي إلى إقليم أقطانيا، وسار في الطرف الغربي من فرنسا باتجاه الشمال، ثم انحرف باتجاه الشرق والجنوب إلى مدينة آرليس فأعاد فتحها وحصَّن المسلمين فيها، ثم عاد إلى أقطانيا وكان حريصاً على أن يصلها بسبتمانيا، لتمكين المسلمين من كلا الإقليمين معاً.

معركة تور (732)

Odo still found the opportunity to save his grip on Aquitaine by warning the rising Frankish commander Charles Martel of the impending danger against the Frankish sacred city of Tours. Umayyad forces were defeated in the Battle of Tours in 732, considered by many the turning point of Muslim expansion in Gaul. With the death of Odo in 735 and after putting down the Aquitanian detachment attempt led by duke Hunald, Charles Martel went on to deal with Burgundy (734, 736) and the Mediterranean south of Gaul (736, 737).

التوسع حتى پروڤانس وشارل مارتل

Nevertheless, in 734 Umayyad forces (called "Saracens" by the Europeans at the time) under Abd el-Malik el Fihri, Abd al-Rahman's successor, received without a fight the submission of the cities of Avignon, Arles, and probably Marseille, ruled by count Maurontus. The patrician of Provence had called Andalusi forces in to protect his strongholds from the Carolingian thrust, maybe estimating his own garrisons too weak to fend off Charles Martel's well-organised, strong army made up of vassi enriched with Church lands.

Charles faced the opposition of various regional actors. To begin with the Gothic and Gallo-Roman nobility of the region, who feared his aggressive and overbearing policy.[13] Charles decided to ally with the Lombard King Liutprand in order to repel the Umayyads and the regional nobility of Gothic and Gallo-Roman stock. He also underwent the hostility of the dukes of Aquitaine, who jeopardized Charles' and his successor Pepin's rearguard (737, 752) during their military operations in Septimania and Provence. The dukes of Aquitaine in turn largely relied on the strength of the Basque troops, acting on a strategic alliance with the Aquitanians since mid-7th century.

In 737, Charles captured and reduced Avignon to rubble, in addition to destroying the Umayyad fleet. However, Charles' brother, Childebrand, failed in the siege of Narbonne. Charles attacked several other cities which had collaborated with the Umayyads, and destroyed their fortifications: Beziers, Agde, Maguelone, Montpellier, Nîmes. Before his return to northern Francia, Charles had managed to crush all opposition in Provence and Lower Rhone. Count Maurontus of Marseille fled to the Alps.

خسارة المسلمين لسپتيمانيا

Muslims maintained their authority over Septimania for another 15 years, but shifted the focus of their efforts towards the internal divisions within al-Andalus, that had been caused by the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750. In 752, the newly proclaimed Frankish king Pepin, the son of Charles, launched an invasion of Septimania to take advantage of the internal troubles of the Muslims in al-Andalus and the growing disaffection of the Gothic nobility with their Muslim rulers. That year, Pepin conquered Nimes and went on to subdue most of Septimania up to the gates of Narbonne. In his quest to subdue the region, Charles met the opposition of Waiffer the Duke of Aquitaine. Waifer, aware of Pepin's expansionist ambitions, is recorded as attacking the Frankish rearguard with an army of Basques during the siege of Narbonne.

It was ultimately the Frankish king who managed to take Narbonne in 759, after vowing to respect Gothic law and earning the allegiance of the Gothic nobility, thus marking the end of the Muslim presence in southern Gaul. Furthermore, Pepin directed all his war effort against the Duchy of Aquitaine immediately after subduing Roussillon.

Pepin's son, Charlemagne, fulfilled the Frankish goal of extending the defensive boundaries of the empire beyond Septimania and the Pyrenees, creating a strong buffer zone known as the Spanish March between the Frankish Empire and the Umayyad Emirate. The Spanish March would in the long run become a base, along with the Kingdom of Asturias, for the eventual Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

معركة نهر الجارون

كان أودو حاكم أقطانيا قد جمع للغافقي كل ما استطاع، وكان حاكماً ذا سلطة ونفوذٍ وعلى اتصال مستمر ببابا الكنيسة في روما، ويطلق على نفسه لقب أودو العظيم، فخرج للقاء الغافقي، واصطدم الجيشان في معركة نهر الجارون، والتي كان النصر فيها حليف المسلمين، وكثر القتل في جيش أودو، حتى قال بعض المؤرخين: إن الله وحده يعلم عدد القتلى.[14]

وبعد هذه المعركة الحاسمة، فتحت مدن ومقاطعات أقطانيا بالكامل[15]، ويشار من بينها إلى مدينة بوردو عاصمة الإقليم[16]. وصل عبد الرحمن الغافقي إلى بواتييه ففتحها، ثم وصل إلى تور الواقعة على نهر اللوار وفتحها أيضاً[17]، وبذلك بات على مشارف ممالك الشمال الجرمانية والفرنجية.

بعد معركة نهر الجارون

يرى بعض المؤرخين أن الغافقي لم يكن ينوي التقدم أكثر من ذلك، بل كان ينوي تحصين المدن المفتوحة وتقويتها لتصبح ثغراً للمسلمين، كما هي الحال في سبتمانيا، ولم يكن معه من الجند ما يكفي لفتح مدن أكثر، فبعد مسيرة طويلة في جنوب غالة وغربها، وبعد معركة نهر الجارون، لم يكن قد بقي معه أكثر من 10-30 ألف مقاتل[18].

أما قارلة -الملك الفعلي للفرنجة- فقد كان يعمل طوال فتوحات الأمويين في غالة على أن يظل بعيداً نائياً بنفسه عن مواجهتهم، على الرغم من أنَّ حملاتهم كانت على مقربة من أرضه، بل وقد دخلت حدود أرضه أحياناً كحملة عنبسة بن سحيم الكلبي التي افتتحت إقليم بورغانديا بالكامل الذي هو جزء من مملكة قارلة، ووصلت سراياها حتى سفوح جبال فوسغس في قلب مملكة الفرنجة[19]، ولكن قارلة لم يصطدم معهم، كما تشير المصادر التاريخية الإسلامية أيضاً إلى أن حملة عنبسة لم تلق مقاومة تذكر[20]، وأنه آثر العودة إلى قاعدته لأسباب استراتيجية، لأنه شعر أنه توغل كثيراً في أرضٍ لا تزال مجهولةً بالنسبة للمسلمين[21][22]، وتذكر بعض هذه المصادر أيضاً (مثل ابن عذاري وابن الأثير)[23][24] أن عنبسة مات ميتة طبيعية ولم يُقتَل في طريق عودته.[25]

يعتقد بعض المؤرخين (مثل عبد الرحمن علي الحجي) أن قارلة رأى أن المسلمين أشداء في معاركهم وفتوحاتهم، وأن مواجهتهم وهم في أوج قوتهم ليست في صالحه، فترك أقطانيا وغيرها -وهم خصوم قارلة الذين أجبرتهم غزوات المسلمين على اللجوء إليه والتحالف معه- ينالهم من المسلمين ما ينالهم، في حين أخذ يعد ما بوسعه هو من العدد والعتاد للاشتباك في الوقت المناسب.[26] وبعد انتصارات المسلمين في غالة قرر تشارلز بالفعل أن الوقت قد حان للقائهم مباشرة بعد أن خاضوا حروبهم الأخيرة، وألا يتيح المجال أمام الغافقي كي يوطد نفسه ورجاله، ويعيد تجديد حملته، ويجلب الإمدادات.

وصادف ذلك قدوم أودو -منافس قارلة- إليه، وكان أودو قد أعاد لمَّ رجاله وقواته، ولكنها لم تكن تكفيه كي يستعيد ملكه، فطلب من قارلة أن يساعده في استعادة أقطانيا[27][28]، وكان هذا ما أراده تشارلز، حيث أخذ من أودو ميثاقاً بالولاء له ولدولته، وكان له ما أراد، فتحالف هكذا أودو العظيم مع تشارلز مارتل ضد المسلمين[29].

قوات الشمال تزحف باتجاه رافد اللوار

خرج قارلة بجيش كبير جداً[30]، حيث كان قد جلب مرتزقة ومقاتلين من حدود الراين[31] وقوات من بورغانديا، ومتطوعين من كل أنحاء أوربا وبرعاية من بابا الكنيسة في روما، كما انضم إليهم أودو بفلول جيشه، فبات جلياً أن انهزام الجيش سيعني انكسار ممالك أوربا كلها.

كان عبد الرحمن قد وصل إلى تور مع من تبقى من جيشه، وكانت حملته بحاجة إلى الدعم بالإمدادات لتعويض ما خسرته من جنود في أقطانيا وكاتالونيا وسبتمانيا وغيرها سواء في المعارك التي خاضتها أو في الحاميات التي خلفتها ورائها أو غير ذلك.[32][33]

أراد قارلة ألا يتيح هذا المجال أمام الغافقي، وأن يسارع لمواجهته في هذا التوقيت، فاختار زمن المعركة الذي يناسبه، كما أنه أراد أن يختار أرض المعركة أيضاً، خصوصاً وأنه كان قد سبق لجيش المسلمين أن انتصروا مراراً في معارك حاسمة كانوا فيها قلة كاليرموك ومعركة وادي لكة.

يرى شوقي أبو خليل أن قارلة لم يكن مسيحياً متديناً، وأنه لم يحارب من أجل الصليب، بل غلب على طبعه وسياسته العكس تماماً، ويستدل على ذلك بأن كثيراً من مقاتليه كانوا مرتزقة وثنيين (خصوصاً أبناء القبائل الجرمانية)غلبت على معتقداتهم الأساطير والخرافات،[34] كما يستدل على ذلك أيضاً بأن شارل مارتل نفسه -كما يقول شوقي أبو خليل- كان إذا هاجم أراضي خصومه ومنافسيه لا يتورع عن تهديم الكنائس مع أنه كان مسيحياً.[34]

ويتابع شوقي أبو خليل قائلاً: "وفضلاً عن ذلك، فإن قارلة ((شارل مارتل)) عندما استرجع أملاك الكنائس والأديرة، لم يردها على أهلها بل وزعها على رجاله".[35]

رأى قارلة أن مواجهة المسلمين وهم متحصنون في تور قد تكسر كثرة جيشه، فرأى أن يستدرجهم إلى خارج المدينة إلى السهل الواقع غرب رافد نهر اللوار، حيث سيمكنه هذا السهل من محاصرة المسلمين من الخلف، ومن أكثر من جهة، معززاً بذلك تفوق عامل الكثرة الذي يتمتع به جيشه.

مع الإشارة هنا إلى أن هذا السهل هو سهل أحراش، الأمر الذي ساعد المسلمين نوعاً ما في صمودهم في المعركة، في حين يرى آخرون -ومنهم الغنيمي- أن الأحراش لعبت دوراً سلبياً بالنسبة للمسلمين.

أرسل قارلة فرقاً صغيرة من طلائع جيشه إلى الضفة الشرقية من النهر، فعندما علم بأمرها عبد الرحمن، أرسل فرقاً استطلاعية لكشفها، وعادت تلك الفرق تخبره أنها فرق قليلة العدد يسهل القضاء عليها، فخرج عبد الرحمن من المدينة لمواجهتها، وبذلك تحقق لقارلة ما أراد، فعندما عبر الغافقي وقواته إلى ضفة النهر الشرقية، حرك قارلة قواته باتجاه أرض المعركة، وكانت مهولة الكثرة كالطوفان المندفع كما يصفها شوقي أبو خليل.[36][37]

عندما رأى عبد الرحمن هذا الجمع الهائل ارتد بقواته إلى السهل بين تور وبواتييه[37][38]، فقد أدرك عندها ما أراده عدوه، وأنه أراد الإيقاع به وبقواته في السهل، حيث سيظهر تفوق العدد بشكل واضح.

أخذ عبد الرحمن يعد بعض التحصينات، ومن المحتمل أنه عمد إلى حفر خندقٍ حول مؤخرة الجيش كي يحبط محاولات الفرنجة للاتفاف عليه، ومما يشير إلى ذلك اكتشافات حديثة لسيوف عربية هناك في منطقة تدعى خندق الملك Fossi le-Roi وفق ما أورده الأستاذ الدكتور عبد الرحمن علي الحجي[39] وأشار إليه أيضاً الدكتور الغنيمي[40]، والمرجح أن المقصود بالملك هو عبد الرحمن الغافقي، والخندق هو الخندق الذي عمد إلى حفره، ولكن الظاهر أن هذا الخندق كان سريع الإعداد هش المفعول ولم يتسن للمسلمين الوقت كي يكملوه كما يجب.

تقدم قارلة بقوات الشمال ونزل على مواجهة مع الجيش الأموي، استعداداً للمعركة، حيث انحرف الجيش الأموي قليلاً وتجمع في جهة الجنوب باتجاه بواتييه -كي يؤمن اتصاله بالجنوب-، وكان جيش أوربا ينحرف قليلاً ويتجمع في جهة الشمال باتجاه تور -كي يؤمن اتصاله بالشمال-[41].

معركة بلاط الشهداء

مقالة مفصلة: معركة بلاط الشهداء

مقالة مفصلة: معركة بلاط الشهداء

استمرت بين الجيشين مناوشات لحوالي 9 أيام، انتهت بشن المسلمين للهجوم في اليوم الأخير، يرى بعض المؤرخين أن قارلة عمد إلى تعزيز كثرة قواته وموقفه بإطالة أمد المعركة، فأرسل يطلب المزيد من المدد من المدن المجاورة في حين أن الغافقي كان يحتاج لكل مقاتليه في المعركة، ولا يمكنه أن يتخلى عن بعضهم كي يرسلهم في طلب المدد، كما أن الطرق لم تكن مؤمنة بعد بما يكفي للرسل الأمويين -يشار هنا بشكل خاص إلى جبال الأبواب والتي كان عبورها مغامرة خطرة في ذلك الوقت-، وهذا الأمر لعب دوراً دفع الأمويين لشن الهجوم في اليوم الأخير، كي لا تطول المعركة وتزيد الإمدادات القادمة لقوات الشمال. يضاف إلى ذلك أن الأمويين قليلو العدد ستكثر جراحهم ويقل عددهم أكثر إذا طالت المعركة.

وقدأشارت إحدى المصادر إلى أن الغافقي لو أرسل في طلب المدد، فلن يصله هذا المدد في أقل من شهر -في أحسن الأحوال-، أما قارلة فكان يقاتل في أرضه وبلاده وبين شعبه، وأرض المعركة نفسها خط إمداد له.[42]

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ Tricolor and crescent: France and the Islamic world by William E. Watson p.1

- ^ أ ب ت Watson 2003, p. 1.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Watson 2003, p. 11.

- ^ أ ب ت Collins 1989, p. 45.

- ^ Collins 1989, p. 96.

- ^ Collins 1989, p. 213.

- ^ Collins 1989, p. 89.

- ^ د. طارق السويدان، الأندلس التاريخ المصور، ص 65

- ^ الحجي ص193

- ^ الحجي ص52

- ^ أبوخليل ص23

- ^ الفجر، ص303

- ^ Collins 1989, p. 92.

- ^ عنان ص90. تذكر المخطوطة المستعربية اللاتينية العبارة التالية: "solus Deus numerum morientium vel pereuntium recognoscat"

- ^ الغنيمي ص65

- ^ الحجي ص205

- ^ الغنيمي ص64

- ^ الفجر، ص216

- ^ الفجر ص317

- ^ أبوخليل ص13

- ^ دكتورة منى ص26.

- ^ أبوخليل ص14.

- ^ ابن عذارى (البيان المغرب، ج2، ص26).

- ^ ابن الأثير (الجزء5، ص373).

- ^ الفجر ص313.

- ^ الحجي ص196

- ^ الغنيمي ص63

- ^ أبوخليل ص18

- ^ أبوخليل ص30

- ^ الحجي ص202-204

- ^ الحجي ص202

- ^ الفجر ص216

- ^ مقلد الغنيمي ص67

- ^ أ ب بلاط الشهداء، لأبي خليل ص41

- ^ بلاط الشهداء، لأبي خليل ص43

- ^ أبوخليل ص25

- ^ أ ب عنان ص99-100

- ^ الغنيمي ص66

- ^ الحجي ص194

- ^ الغنيمي ص76

- ^ الغنيمي ص66-67

- ^ مقلد الغنيمي ص65-66