معرض الرياض الدولي للكتاب

| معرض الرياض الدولي للكتاب Riyadh International Book Fair | |

|---|---|

شعار معرض 2019 | |

شعار معرض 2020 | |

| الحالة | نشط |

| الصنف | متعدد الأنواع |

| الافتتاح | الثلاثاء (يوم الافتتاح، ولكن ليس للجمهور)[1] |

| الانتهاء | السبت (اليوم العاشر ما عدا يوم الافتتاح)[أ] |

| التكرار | سنويًا في منتصف مارس إلى أبريل |

| الموقع | مركز الرياض الدولي للمؤتمرات والمعارض |

| المكان | الرياض |

| البلد | المملكة العربية السعودية |

| المنظم | في الأصل شركة معارض الرياض. ومع ذلك، في عام 2006، قالت إنها وقعت اتفاقية تعاون مع وزارة التعليم العالي في المملكة العربية السعودية لإدارة المعرض.[5][6]

في وقت لاحق، وزارة المعلومات والثقافة[7] وبعد الفصل ،[8] تولت وزارة الثقافة .[9] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | URL has changed[10]

|

معرض الرياض الدولي للكتاب هو معرض كتاب سنوي يقام في المملكة العربية السعودية، ويستمر ل11 يوم[13] ويجذب عادة أكثر من نصف مليون زائر[14] على عكس ما يدعيه البعض[15]). ويشارك الكتاب في الفغاليات الأدبية. ويناقش المتحدثون المدعوون والجمهور القضايا الفكرية والاجتماعية. تقوم وزارة الثقافة والإعلام بتنظيم المعرض.[9][6]

الأنشطة

يهدف المعرض إلى توفير حرية الوصول إلى الأدب، وتتوفر مجموعة كبيرة،[16] بما في ذلك بعض الكتب المحظورة أو التي لا تباع عادة في المملكة العربية السعودية.[4][7] الاحتجاجات على المواد في المعرض شائعة.[16] بينما تفرض السلطات رقابة مسبقة على الكتب، فإنها أحيانًا تصادر الكتب التي تمت الموافقة عليها مسبقًا أثناء المعرض.[13] يقول الناشرون إنهم سيمنعون من دخول السوق السعودية إذا تحدثوا بصراحة عن حظر الكتب.[16] أصبح معرض الكتاب موضوعًا للجدل السياسي، حيث تم الإشادة به لتوفير الوصول إلى الكتب المفيدة ودعم الثقافة والمجتمع، وانتُقد بسبب الرقابة غير الكافية أو المفرطة أو غير الملائمة.[9][16][17] تساعد ندرة الأحداث العامة في المملكة العربية السعودية، وأنشطة الأطفال، على جعلها شائعة لدى عامة الناس.[7]

بصرف النظر عن بيع الكتب، يستضيف المعرض أيضًا الكتاب والشعراء والمثقفين الذين يلتقون بالجمهور. يوقعون الكتب، يشاركون في حلقات النقاش العامة،[7] ويلقون محاضرات عامة.[18] يقدم المؤلفون قراءات عامة لأعمالهم، دون مناقشة عامة للقراءات.[7]

كانت هناك بعض القيود القائمة على نوع الجنس على القبول: في بعض الأحيان كان الرجال فقط،[19] والبعض الآخر "للعائلات فقط"، مما يعني أن الرجال غير المتزوجين لا يجوز لهم الدخول.[4] من عام 2008 إلى عام 2011، كانت هناك أربع أمسيات للرجال فقط؛ كانت الأوقات الأخرى مفتوحة "للجميع"، مما يعني فقط مجموعات عائلية مختلطة الجنس (لم تكن هناك أوقات مخصصة للنساء فقط). [ب] في عام 2012، لم تكن هناك أوقات قبول منفصلة، وكان يُسمح للرجال والعائلات بالحضور في وقت واحد لأول مرة.[20][18] من الناحية العملية، يحضر معظم مجموعات المدارس في الصباح، ومعظم زوار المساء هم من الرجال؛ النساء والعائلات أمر شائع طوال اليوم.[18]

بشكل منفصل، هناك قيود على أساس الجنس على الأنشطة داخل المعرض. تحتوي جلسات توقيع الكتب والمناقشة عمومًا على مساحات منفصلة بين الجنسين.[7] وبحسب وسائل الإعلام المحلية، فقد مُنع الرجال من توقيع مؤلفاتهم على كتبهم.[16][21] أوضح رئيس Haiʾa في المعرض في عام 2009: "إذا كانت الكاتبة امرأة، يجب أن يتم توقيع كتابهم من خلال طرف ثالث لمنع اتصالها المباشر مع الجمهور". [22] وتشارك عضوات في اللجنة في حلقات عن طريق الاتصال الداخلي، الأمر الذي وجده عضو في اللجنة من خارج المملكة العربية السعودية مقلقًا.[4] تستمع النساء إلى المحاضرات من الشرفة عند عدم إعطائها.[18] تعرض معرض الكتاب لانتقادات لدعمه الاختلاط بين الجنسين.[9] في مناطق الأطفال، يُسمح فقط للنساء والأطفال؛ يتم استبعاد الرجال بشكل صارم. [22][23]

وقد تم تنظيم المعرض من قبل هيئة الأمر بالمعروف والنهي عن المنكر (Haiʾa، الشرطة الدينية)، التي تفرض الفصل بين الجنسين وتقدم المشورة بشأن الملبس.[22] تم منع الرجال من الدخول إذا كان شعرهم طويلاً للغاية.[16] وزعم بعض الرجال الذين قاطعوا الأحداث أنهم أعضاء في هيئة الأمر بالمعروف والنهي عن المنكر.[24]

جوائز مسابقة الكتاب 100،000 ريال سعودي (حوالي 26،000 دولار أمريكي، اعتبارًا من 2016). حتى عام 2016، تم اختيار الفائزين من قبل وزارة الإعلام، ولكن في عام 2016 تم تحديد المسؤولية لمجموعة من أساتذة جامعة الملك سعود. [7]

أقيمت استوديوهات تلفزيونية مؤقتة داخل المعرض، ومقابلات مع مؤلفيها، وهناك العديد من المراسلين المتجولين وفرق التصوير، ولكن تم حظر الكاميرات الشخصية، اعتبارًا من 2012.[18]

السياق السياسي

معرض الرياض للكتاب هو بؤرة الصراع السياسي: من السهل فهم أحداثه في سياقها السياسي. يحتفظ الملك بالسلطة في المملكة العربية السعودية (اعتبارًا من 2020، فعليًا ولي العهد، محمد بن سلمان)، ولكن أيضًا تقليديا أيضًا من قبل العائلة المالكة ورجال الدين والأجهزة الأمنية المتداخلة ومجتمع الأعمال، الذين كانوا تقليديًا متحالفين.[27][28] هذه التحالفات ليست صامدة كما كانت في السابق،[27][28] لأن النظام الملكي يركز على السلطة ويضعف قواعد القوى الأخرى. [29][28]

يتمتع عامة الناس ووسائل الإعلام (بما في ذلك الصحف وناشرو الكتب) بسلطة رسمية قليلة، لكن قوتهم المحتملة كانت مصدر قلق رسمي. منذ عشرينيات القرن الماضي، وعد النظام الملكي مرارًا وتكرارًا بإصلاحات ديمقراطية وملكية دستورية. ومع ذلك، في 2010، أكدت الملكية المطلقة.[30]

العائلة المالكة

كان هناك صراع على السلطة بين النظام الملكي والعائلة المالكة. غالبًا ما يشغل أفراد العائلة المالكة مناصب رسمية، في الحكومة أو الأوساط الأكاديمية. وبالتالي، فإن بعض المؤلفين والمفكرين العامين في المعرض هم أعضاء في العائلة المالكة (على سبيل المثال، الزهراني هو اسم العائلة المالكة الثالثة، واسم أستاذ القانون الذي انخرط في اشتباكين مع رجال الدين في معرض الكتاب). فقدت العائلة المالكة الكبيرة مؤخرًا سلطتها السياسية.[31] تم استبدال المسؤولين الملكيين بمسؤولين مدينين لولي العهد. [32] في عام 2018، تم وضع أفراد العائلة المالكة ومجتمع الأعمال رهن الإقامة الجبرية،[29] وطُلب منهم التوقيع على الأصول للحكومة ،وتقييد تحركاتهم؛ هناك تقارير عن تعرض البعض للاعتداء الجسدي، وهو ما تنفيه الحكومة[33][34][35] (التعذيب غير قانوني في المملكة العربية السعودية.[36]). تم زيادة الرواتب لأفراد العائلة المالكة سرا. [37]

المسؤولين الدينيين

كان هناك أيضًا صراع على السلطة بين النظام الملكي والمسؤولين الدينيين. يتحكم المسؤولون الدينيون في التعليم والقضاء (على الرغم من أن الملك قد يصدر العفو). قام المسؤولون الدينيون تقليديًا بمراقبة الصحفيين والمطبوعات، من خلال سيطرة وزارة الداخلية (كذا).[38] وزارة الداخلية كانت تشرف في السابق على هيئة الأمر بالمعروف، لكنها خسرتها في أوائل عام 2010.[39] في عام 2017، تم نقل قوى الأمن الداخلي والنيابة القوية من سيطرة الوزارة إلى السيطرة المباشرة على النظام الملكي.[28] تم تقييد سلطات رجال الدين في معرض الكتاب بشكل متزايد؛ على سبيل المثال، فقدت هيئة الأمر بالمعروف والنهي عن المنكر سلطة إنفاذ القواعد، واحتفظت فقط بسلطة الإبلاغ عن الانتهاكات، وذكرت وسائل الإعلام التي تسيطر عليها الحكومة أن أعضاء الهيئة الذين عطلوا أحداث معرض الكتاب في 2010 قد تم اعتقالهم.[23]

الإعلام

يتم تعيين رؤساء التحرير في المملكة العربية السعودية فقط بموافقة الحكومة، ويعملون على إرشادات حول كيفية تغطية الأخبار. الصحف تخضع للرقابة اللاحقة؛ يمكن للحكومة أن تضع أي صحفي في قائمة سوداء في المملكة العربية السعودية، وتمنعه من العمل في أي مكان في البلاد، ويمكنها حذف المقالات عبر الإنترنت.[38] كما تعرض الصحفيون للاعتقال والاحتجاز في الحبس الانفرادي والتعذيب لأسباب غير واضحة في كثير من الأحيان.[40] غالبًا ما يحضر الصحفيون المعرض كمؤلفي كتب. نسب أحد الصحفيين الاشتباك مع هيئة الأمر بالمعروف والنهي عن المنكر في المعرض إلى أعمدة الصحف الخاصة بها؛[41] لقد انتقدت الهايلا،[41] كما ضعفت سلطة Haia على الرقابة.[41] كما تخضع الكتب ودور النشر بأكملها للرقابة؛ أي شخص يريد الوصول الشامل إلى السوق السعودية يحتاج إلى موافقة الرقباء.[42][16]

تم وضع برنامج معرض الكتاب من قبل النظام الملكي، والذي يستخدمه لعرض سياساته؛[7][43] ويفرض النظام الملكي أيضًا الرقابة المسبقة على الكتب التي سيتم بيعها بشكل قانوني.[13] يتم تنظيم الحدث من قبل هيئة الأمر بالمعروف والنهي عن المنكر، التي وضعت قواعد القبول والكتب المصادرة والرقابة اللاحقة، وأغلقت الأحداث.[7][4]

أصبحت الرقابة في معرض الكتاب، كما في أي مكان آخر، أقل تديناً وأكثر سياسية في أهدافها، حيث تم نقلها من السيطرة الكتابية إلى السيطرة الملكية. دافع الليبراليون الاجتماعيون أحيانًا عن حرية التعبير للمحافظين الاجتماعيين، الذين يواجهون الآن رقابة أشد في المعرض وأماكن أخرى.[44] كما تواجه وسائل الإعلام غير الرسمية قيوداً أقوى؛ تم سجن أشخاص وتعذيبهم بسبب مشاركات على المدونات والتغريدات. [45][36][33] تعيق المدونات ووسائل التواصل الاجتماعي والقنوات الفضائية من الرقابة؛[46] تمت مناقشة 5 كتب ممنوعة من معرض الكتاب على الإنترنت، ومتاحة للكثيرين من خلال التنزيلات غير القانونية. [47]

أنفقت الحكومة السعودية الملايين على التأثير في التغطية الإعلامية الأجنبية، لا سيما في أعقاب وفاة جمال خاشقجي عام 2018. وتركزت الجهود على تحسين صورتها الدولية، وجذب السياح، والترويج للمناطق السياحية.[48][49]

الرأي العام

يسعى زوار المعرض (من الجمهور والكتاب والمثقفين) إلى التهرب من الرقابة، وشراء وبيع الكتب، بما في ذلك كتب السوق السوداء،[7][4] والمشاركة في المناقشات. [53] إنهم يتعارضون مع كل من النظام الملكي والشرطة الدينية، وكذلك مع بعضهم البعض.[23]

تقليديا، قدم النظام الملكي نفسه كقوة تقدمية، ممنوعة من التحرك بسرعة مع الإصلاحات التحررية من قبل المحافظة القوية للسكان؛[54] ضمنيًا، إذا أصبحت البلاد ديمقراطية، فستصبح أكثر محافظة جذريًا. تم الطعن في هذا الرأي محليًا.[55] كما تم اقتراح أن النظام الملكي يسعى إلى إعاقة حركة سياسية سعودية موحدة من خلال إثارة الخلافات القبلية والمذهبية الدينية، وربط المظاهرات والعصيان المدني والنقد بجهات أجنبية.

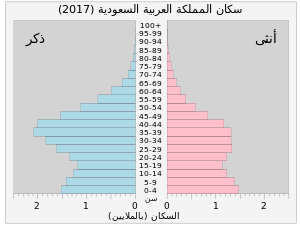

من عام 2003 إلى 2005، كانت هناك التماسات لحقوق الإنسان وملكية دستورية.[56] خلال الربيع العربي، احتجاجات المملكة العربية السعودية 2011-12، تجددت هذه الاحتجاجات، مع نداءات عامة والتماسات من أجل الديمقراطية.[30][57] كانت الدعوات للإصلاح مدفوعة بالفساد، والإفلات من العقاب، والاحتجاز دون محاكمة، والبطالة المرتفعة، والتجاوزات الملكية. [58] العمال الأجانب في المملكة العربية السعودية، الذين يشكلون حوالي 30٪ من السكان (أرقام التعداد الرسمية، اعتبارًا من 2014)[59] لديهم حقوق محدودة ومحرومون من حقوقهم، وهو مصدر محتمل إضافي للاضطرابات.[60]

There was also significant activism on guardianship rules, women's franchise, the right to drive, and the rights of political prisoners.[54] A 2013 petition called for women to be permitted to drive[61] (a position which a Gallup poll found that the majority of Saudi men and women supported in 2007,[62] contradicting a 2006 government poll finding 89% of women opposed it[50]). Some petitions, like a 2016 one to abolish the male guardianship system, were supported by clerics and social liberals.[63][64]

The monarchy has taken action against independent and opposition clerics, usually on the grounds that they support extremism or terrorism. It has arrested clerics of a variety of political views, including some who have supported religious tolerance and opposed travel to fight in war zones,[65] and those supporting electoral democracy.[66] Generally, overt support of crown prince Mohammad bin Salman is required: in some cases, this includes performing specific requested acts of support.[28] The clerics who are tolerated all support the crown prince, though they vary in their other views.[65] This has entailed dramatic shifts in the monarchy's attitude to groups like the Sahwa movement and the Muslim Brotherhood, to whom it had formerly given official positions and influence; one such shift was marked by the banning of all Muslim Brotherhood books from the book fair.[66]

More such shifts have been seen on women's driving. In 2006, a politician was shouted down for raising the topic at the fair;[4] in 2014, a driving activist had an aisle at the fair named after her;[67] in 2017, the government announced that women would be allowed to drive, in 2018, the fair featured a driving simulator for women, women were allowed to drive,[43] non-activist women were asked to publicly thank the government so that the change would not appear to be a victory for the activists,[55] and many activists who had campaigned for the right to drive were arrested (including activists honoured in 2014); in 2019, a professor was arrested after expressing support of the still-detained activists at a fair discussion panel.[68][53]

الإصلاحات: التحرر الاجتماعي، التقييد السياسي

منذ هذه الاحتجاجات، بدأت رسالة النظام الملكي في التحول. وهي تقوم الآن بسن إصلاحات تحررية اجتماعيًا، ضد معارضة العناصر الأكثر تحفظًا من رجال الدين، وكسر التحالف مع بعض رجال الدين المتشددين.[44][27] هناك دافع لتوفير فرص ترفيهية للشباب؛ دور السينما والحفلات الموسيقية مسموح بها الآن، ويتم الترويج للأزياء والفنون والرياضة.[35][45] يوفر معرض الكتاب الذي يتم الترويج له بشكل كبير أيضًا أنشطة ثقافية معترف بها رسميًا، وقد تم تخفيف بعض القيود الاجتماعية في المعرض (مثل قواعد لباس المرأة والفصل بين الجنسين).[69]

يبدو أن الآراء بشأن هذه الإصلاحات الاجتماعية متباينة: فالمواطنون الحضريون الشباب يميلون إلى أن يكونوا أكثر تفضيلًا، في حين أن المواطنين المتدينين المحافظين، الذين ينحدرون من مناطق ريفية معينة، هم أكثر عرضة لمعارضتها.[45] الإصلاحات الاقتصادية، مدفوعة بانخفاض أسعار النفط، لديها مستويات متفاوتة من الدعم، والاقتصاد السيئ هو مصدر الاستياء.[70][60]

يُنظر إلى الإصلاحات الاجتماعية على نطاق واسع على أنها وسيلة لتقليل ضغط الناشطين من أجل إصلاح هياكل السلطة السياسية (مثل زيادة الصوت الشعبي في الحكومة).[45] النظام الملكي يتخذ في الوقت نفسه إجراءات أكثر صرامة ضد المعارضة. بغض النظر عن مدى كونهم ليبراليين أو محافظين، [71] تعرض النشطاء الذين يدعون للإصلاحات السياسية للسجن والتعذيب، حتى عندما دافعوا،[72] أو عملوا مع الحكومة على الإصلاحات التي سنتها الحكومة. [73][40] كما اعتقلت الحكومة الأكاديميين الذين أعربوا عن آراء انتقادية (على سبيل المثال، التشكيك في التوقعات الاقتصادية الحكومية)،[28] بما في ذلك في المعرض. [74]

التاريخ

2004

شارك في معرض 2004 (المُعلن عنه باعتباره العاشر [75]) 300 ناشر من 14 دولة (معظمهم من الدول العربية). كان هناك ناشر عراقي واحد.[76]

2006

The Saudi government (through the Ministry of Higher Education) was involved with organizing the event for the first time in 2006;[6] the Riyadh Exhibitions Company said that they had signed a co-operation agreement.[5]

Some days were restricted to "families-only" attendance, meaning that single men were not allowed to enter. The 2006 fair was held in the Riyadh Exhibition Center.[77][78]

Booths of foreign publishers, such as Dar Al Saqi, The Arabic Cultural Center, Dar Al Jamal, the Arab Establishment of Research and Publishing, and Dar Al Mada, were popular.[4] Copies of the novel Banat al-Riyadh ("Girls of Riyadh") were unexpectedly absent; it was not clear whether it had been banned[4] or had sold out, although a representative of the publisher said it had not sold out, according to a Saudi government-run London newspaper. The same paper reported that The Dolphin's Trip and Terrorist Number 20 were banned, while the New Testament and Dialogue with an Atheist were on display for the first time.[79] Turki Al-Hamad's novel Reeh Al-Jannah was also missing.[4]

Some official speakers and debate topics were controversial, touching on pressing political issues, and debates were heated.[6] A discussion panel was disrupted by hecklers who shouted down a member of the Consultative Assembly of Saudi Arabia[80] (Mohammed Al-Zulfa[4]) speaking at the fair[80] on women's driving.[81] A discussion on censorship, whose panelists included former Information Minister Muhammad Abdo Yamani and pro-government editor Turki al-Sudeiri, was shouted down by protestors, who also surrounded the panellists and physically assaulted at least one journalist.[38]

2007

أقيم معرض عام 2007 في نفس الموقع مثل معرض عام 2006، ووصفت الموضوعات المختارة للبرنامج الثقافي بأنها أقل إثارة للجدل.[77]

في عام 2007، أعلن عبد العزيز السبيل، نائب وزير الإعلام للشؤون الثقافية، أنه سيتم إلغاء أيام "العائلات فقط": ثلاث أمسيات مفتوحة للرجال فقط؛ سيكون الباقي مفتوحًا للجميع. وقيل إن الوزارة والهيئة تفاوضوا على هذا التغيير.[77][80] ومع ذلك، ليس من الواضح ما إذا كان هذا قد حدث بالفعل؛ اتضح لاحقًا أن الفترات العادلة المجدولة على أنها "مفتوحة للجميع" تعني مفتوحة للمجموعات العائلية المختلطة فقط. [10]

2008

أقيم معرض عام 2008 في مركز الرياض الدولي للمعارض في حي المروج، وشمل متحدثين وموضوعات أقل إثارة للجدل من معرض عام 2006.[6]

وقدمت الجمعية الوطنية لحقوق الإنسان في المعرض تقريراً عن حالة حقوق الإنسان في السعودية. كانت هناك ساعات عمل منفصلة للرجال ومجموعات عائلية مختلطة،[6] وأربع أمسيات مخصصة للرجال فقط. [82]

وشاركت السفارة الأمريكية في الرياض باستضافة جناح "مركز مصادر المعلومات الأمريكية".[83] باع الكشك 1829 نسخة من 66 مطبوعة معتمَدة سلفا؛ فوجئ مسؤولو السفارة بالاستجابة الإيجابية لوجودهم، والاهتمام الشديد بمواد تدريس اللغة الإنجليزية والأدب الأمريكي.[84]

2009

In 2009, the fair moved to the much larger[22] Riyadh International Exhibition Center on King Abdullah Road,[19] and ran from Thursday 3[24] until 13 March.[19] Four evenings were men-only and the rest were "for all" (meaning open to mixed-gender family groups only[10]), according to the official conference schedule.[85]

Saudi newspapers, which are government-controlled,[38] reported that prices of books from non-Saudi publishing houses were up 20 to 25%, due to the costs of transportation, rental of space at the fair, and other factors. They said that some books that had previously been permitted were banned, and some previously banned were permitted, and that visitors were required to show the receipts for their books on the way out.[86] The government-controlled Saudi Gazette also reported that books by Abdel Rahman Badawi an Amin Maalouf were missing from the fair.[87] Dar al-Jamal, an Iraqi publisher previously popular at the fair,[4] was banned.[20]

Religious scholars condemned the fair for inviting Mohammed Abed al-Jabri. At the fair, al-Jabri said that religious groups sought to monopolise religious authority, by restricting the ability of civic groups to defend religious beliefs.[41]

According to accounts in Saudi newspapers,[89] on Thursday the 5th,[19] local journalist Halimah Matafar's (ar) book-signing was surrounded by five security men, six policemen and two religious policemen.[24][41] They report that some male writers[24] had their books signed; as they left, one waved and said "Thank you and goodbye" to the author,[22][24] and religious police accused him of addressing an unrelated woman.[24] Satirical novelist and journalist[90] Abdo Khal and poet Abdullah al-Thabet[91][92] (and law professor Mojab al-Zahrani, according to some accounts[88][86]) complained that they were then verbally abused and taken to the religious police center;[24] they were released without charge the same day. Halimah Matafar said that she was the only woman at the fair treated in this manner; she attributed it to her criticism (in her weekly column) of the religious police: "I felt like I was wearing an explosive belt, not signing books... If any first-time female writer was surrounded by this many policemen, she would be discouraged," she said.[41]

During the 8th, a woman visiting with her family found only one stall staffed by a woman[22] (likely Najet Mield, per state-controlled sources[87]). The stallkeeper had come from France, and said staffing the stall on the first day, which was men-only, was awkward, so she had gotten a male stand-in for the men-only days.[22] On Friday the 6th (the fourth day), saleswomen were banned from the hall on men's days.[19]

The religious police had a large stall, which did not sell books. It exhibited items they had confiscated, and screened a video presentation on how they reverse magic spells.[22]

2010

The 2010 fair advertised family-only days (no single men) and four men-only evenings.[10][93] It was criticized for its website being hastily thrown up less than a day before the fair, with limited information and some technical problems.[94] The presence of the religious police was much more muted in 2010 than in the previous year, including a smaller stall. Some stallholders were requiring official written notice that a book was banned before removing it from sale (rather than removing books on a verbal request from the religious police).[23] Controversially, a woman did the announcements over the public address system.[23]

The children's area (in which men are not allowed) was greatly expanded, with more children's books, a reading area, a colouring area, a stage with regular performances, and, for mothers, screenings of films on child abuse and domestic violence.[23] The Saudi Human Rights Organization, the Riyadh Orphanage, the disabled association, a temporary museum exhibit, and other organizations had stalls just outside the exhibition hall.[23] There was a small but varied selection of English books.[23]

Abdo Khal's prizewinning[95] novel Tarmi bi-Sharar (English title: Spewing Sparks as Big as Castles[96]) was withdrawn from the fair.[97] Books by activist Abdullah al-Hamed were confiscated.[98]

2011

On the second day[99] of the fair, a group of men (30 according to one Saudi journalist,[100] dozens according to Agence France-Presse,[101] and over 500 according to Al Arabiya[1] [a domestic, and thus government-controlled, news outlet]) appeared to co-ordinate a disruption, targeting writers, publishers, journalists, and female speakers.[102][20] Domestic media stated that they physically assaulted some participants, issued instructions on women's dress and behaviour over a loudspeaker,[99] and harassed women, many of whom left.[103] According to Al Arabiya, one challenged Abdul Aziz Khoja, the Minister of Culture and Information, on the selection of speakers, complaining that they were too liberal.[100] Saudi media reported allegations that the men were Haiʾa members in mufti;[99] a Haiʾa spokesman said the Haiʾa were not involved. Some were arrested (three, according to Sabq.org[103] and Al-bab.com,[104] or 100, according to Al Arabiya, which also said that the remaining protestors staged a sit-in calling for their release[1]). The original source of information on this event is newspapers under the control of the Saudi government; as the government is a party to this dispute, there is a lack of independent reporting.

On the last day of the fair, a hailstorm lead to extensive leaks in the roof of the Riyadh Expo Center, flooding the exhibition hall. Squeegees were used to control the water. The flood forced many publishers to evacuate their sodden books.[105][106]

Dar al-Jamal, an Iraqi publisher, was banned.[20]

2012

In the lead-up to the fair, government authorities warned that only Haiʾa were allowed to deal with religious issues at the fair, and non-Haiʾa religious activists would be held accountable. This was in response to severe disruption at previous fairs.[107] There was also an announcement that women and single men would be allowed to attend simultaneously,[20] for the first time.[18] The Deputy Culture Minister promised that religious police would not harass women who did not cover their faces this year.[108] Security was heavy, likely in response to the previous year's disruption.[9]

A poll found that women at the fair sought socially-critical novels, followed by studies on social and political issues and religious self-help books. Surprisingly, the fair had many books on the challenges the Arab Spring presented to Saudi Arabia, which were very popular.[18]

On 11 March 2012, five days after the 11-day fair opened, 70 Saudi clerics issued a fatwa criticizing the book fair. They complained that the fair was uncensored, and thus allowed perverted literature which encourages ideological anarchy, including texts undermining the truths of Islam, and discussing deviant and pagan religions, sex, and various abominations. They also criticized the fair for being mixed-gender.[9] Religious conservatives did not disrupt the fair as in 2011.[18]

Syrian publishers were banned.[20][108]

2013

The Arab Publishers Association unanimously resolved to boycott the 2013 fair, citing the exclusion of Syrian publishers from the fair, but also the price of stall space and barcode system installation.[109] The barcode system was abandoned the same day in a tweet.[110] About 500 publishers, local and international, participated in the fair.[111]

Sales-tracking devices for publishers have been described as a reaction to under-the-counter sales of banned books.[7]

Women and single men were again allowed to attend simultaneously, and the Haiʾa announced that they would only be reporting problematic books to the Ministry, not confiscating them themselves.[112]

2014

Over 570 publishers, local and international, participated.[111]

420 books were banned at the 2014 fair, and 10,000 copies of them were confiscated. The bans were described as prompting readers to download the banned books.[113][47]

The late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish's books were confiscated during the fair, after the stall was surrounded by protesters. There were also complaints from religious police and allegations that the poems contained blasphemous passages.[16] Similar actions were taken against works by well-known poets Badr Shaker al-Sayyab, Abdul Wahab al-Bayati, and Muin Bseiso.[114][113][115]

The Arab Network for Research and Publishing, arriving at the former location of their stall on the Friday morning of the 2014 fair, found that it had been dismantled overnight, with their books confiscated, their materials scattered on the floor just outside, and the signage on their stall replaced by signage naming another publisher.[13][91] The group's publishing focusses on nonfiction[91] about Saudi Arabia and political Islam. The books had been pre-approved, and most were sold in previous years; the reversal of the decision was attributed to the tenser political situation. The publisher was reportedly permanently banned from the fair.[13][116][91]

Azmi Bishara's books were also banned amid escalating tensions with Qatar.[114][113] Other banned books included Revolution 2.0, by Wael Ghonim, When will the Saudi Woman Drive a Car? by Abdullah Al Alami,[117] and Al Estbdad ("The Tyranny"), by Ahmed bin Hamad al-Khalili, the Grand Mufti of Oman.[111] The titles The History of Hijab and Feminism in Islam were also banned.[117]

Madeha al-Ajroush, a photographer and activist who campaigned for women's right to drive, had an aisle at the fair named after her. The fair also featured a book on the driving protests, Sixth of November, by Aisha al-Mana and Hissa al-Sheikh.[67]

2015

Sales of the compilation book On the meaning of Arab Nationalism: Concepts & Challenges were permitted at the fair, but banned outside the fair.[7] Haiʾa presence was less conspicuous this year.[7]

A seminar entitled "Youth and Arts... A Call for Coexistence" was stopped by religious police after professor Mojab al-Zahrani condemned the destruction of monuments by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.[118][119] They accused the speaker of idolatry.[120]

The fair ended with a statement that anyone distributing printed materials, books or videos to visitors without prior authorization would face questioning by security authorities.[119]

2016

The 2016 fair was noted for its military themes, centered around the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen[7] (which began in 2015). The Minister also praised the theater in his opening speech.[7]

The opening day was noted for its international and rich local guests, and a temporary relaxation of gender segregation and women's dress codes, tightened again for the following days.[7] A Kuwaiti author was told not to smile, as this showed his dimples, which were considered seductive.[121][118]

The US government was questioned about praise its diplomats gave the fair in light of anti-semitic texts on sale. The fair also included misogynistic books, such as Women Who Deserve to go to Hell by Mansour Abdel Hakim.[122][123] The US State Department later condemned the anti-semitic books and other hate speech, distancing itself from the fair.[124]

Electronic tracking of books was implemented in an attempt to prevent under-the-counter sales of unapproved books.[118]

Journey to a Land Not Ruled By Allah, by Ibrahim al-Tamimi, was reported banned after conservatives tweeted objections to it using the "Campaign Against Atheist Accounts" hashtag.[123] The fair's selection tended towards academic and technical subjects, avoiding books on sex, politics, and religion.[7]

2017

Youssef Ziedan's books were confiscated midway through the 2017 fair, which he attributed to his mention of the disputed Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir.[125]

12 students of the Sekolah Seni Malaysia Johor Art School, performing a Malaysian folk dance, were interrupted by a heckler; other spectators told the heckler to leave the students alone. The religious police took prompt action and stopped the performance.[125] A young Malaysian painted murals during the event.[126]

2018

Held months after women were legally permitted to drive, the fair featured a booth with a driving simulator for women.[43]

A publisher's stall was closed down, and the publisher banned from participating in the fair forever, for selling Muslim Brotherhood books, on grounds that these incited violence and terrorism.[42] This was criticised; Jamal Khashoggi wrote: "Liberals whose work was once censored or banned by Wahhabi hard-liners have turned the tables: They now ban what they see as hard-line, such as the censorship of various books at the Riyadh International Book Fair last month. One may applaud such an about-face. But shouldn't we aspire to allow the marketplace of ideas to be open?"[44]

The Simon Wiesenthal Center documented the display of antisemitic conspiracy texts at the fair, and requested that texts that inflame hatred against Jews be treated in the same manner as the Muslim Brotherhood texts were.[42][127]

2019

Anas al-Mazrou, a law professor at King Saud University, was arrested for speaking of the detention of women's rights activists in Saudi Arabia during one of these panel discussions at the 2019 fair.[74][128] "No one dares to ask, and I am not challenging anybody, including those who are sitting here on stage, to ask about the human rights activists," he said. He named four people as having "contributed to spread the idea of human rights... I will give you an idea and I invite everybody to think about it; the idea of the nation being the guardian of itself, [such that the guardian] is the people, not the ruler"[53] No information was given on where he was taken,[129] and was described on 9 September as having had no contact with his family during this detainment.[130] The video[ت] went viral.[68]

The Simon Wiesenthal Center again complained that the fair sold anti-semitic texts, including Hitler's Mein Kampf. They said that "Of the six Arab Book Fairs we annually monitor, antisemitic texts are sadly the most numerous in Riyadh", and asked the Saudi government to apply the same measures to "all forms of hate, on the same level as offences to Islam".[17][131]

2020

في يوليو 2019، أعلنت وزارة الثقافة السعودية أن معرض 2020 سيعقد في الفترة من 2 إلى 11 أبريل[132] في "جبهة الرياض".[133] ومع ذلك، في 5 مارس، أعلنت الوزارة عن تأجيل المعرض، كإجراء احترازي ضد تفشي مرض فيروس كورونا في جميع أنحاء العالم.[134]

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت "Saudi conservatives stir row in a Riyadh book fair". العربية نت (in الإنجليزية). Alarabiya. 3 March 2011. (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source)

- ^ "Visit to International Book Fair: #Riyadh". Voice of Sudhnoti. 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Riyadh International Book Fair". ACCUCOMS.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س "Exclusive: Riyadh International Book Fair". Saudi Jeans (in الإنجليزية). 25 February 2006. Archived from the original on 1 March 2006.

- ^ أ ب "معرض الرياض الدولي للكتاب Riyadh International Book Fair". Riyadh Exhibitions company. 7 February 2006. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. (official fair website not an independent source)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Al Omran, Ahmed (9 March 2008). "Riyadh International Book Fair: Could Be Better". Saudi Jeans (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ Aldosari, Hala (24 March 2016). "Riyadh Book Fair 2016: A Political Memorandum from New Rulers". Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington.

- ^ "Saudi Culture Ministry formed following a major Cabinet reshuffle". Arab News (in الإنجليزية). 2018-06-02. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Saudi Clerics Criticize Book Fairs, Culture Events in the Country". MEMRI (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Riyadh International Book Fair 2010, let's try this again". Khaled rambles. 3 March 2010.

- ^ The Internet Archive: 2006 website, mostly unarchived English version, February 2007 website; after that, it's held by domain squatters.

- ^ Internet Archive. "Wayback Machine".Archive index at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Omran, Ahmed Al (12 March 2014). "Edgy Saudi Bans Local Publisher". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Williams, Mark (24 February 2019). "As western publishers look the other way millions attend Arab book fairs in February". The New Publishing Standard.

- ^ "Riyadh International Bookfair 2018". Eye of Riyadh. 1 March 2018. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Flood, Alison (14 March 2014). "Saudi book fair bans 'blasphemous' Mahmoud Darwish works after protest". The Guardian.

- ^ أ ب "Mein Kampf and antisemitic books found at Saudi Arabia book fair". The Jerusalem Post. 1 April 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Freitag, Ulrike. "International Book Fair in Riyadh: Treading the Line between Censorship and Cautious Change". Qantara.de - Dialogue with the Islamic World (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Al Omran, Ahmed (7 March 2009). "Riyadh Book Fair '09". Saudi Jeans (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Abdallah, Mariam. "Censorship Rife at Riyadh Book Fair". Ghana News.

- ^ أ ب "Saudi men arrested for seeking female writer's autograph - CNN.com". www.cnn.com.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د "Riyadh Book Fair 2009". Saudiwoman's Weblog (in الإنجليزية). 8 March 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د "Riyadh Book Fair 2010". Saudiwoman's Weblog (in الإنجليزية). 5 March 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Ammar, Hassan (7 March 2009). "Saudi Arabia welcoming more cultural events". msnbc.com (in الإنجليزية). Associated Press.

- ^ Murphy, Caryle (3 April 2014). "Saudi Arabia's Shifting Islamic Landscape". Pulitzer Center (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Al-Mukhtar, Rima (7 November 2012). "Traditional and modern: The Saudi man's bisht". Arab News (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت Chulov, Martin (24 October 2017). "I will return Saudi Arabia to moderate Islam, says crown prince". The Guardian.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "The High Cost of Change: Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms". Human Rights Watch (in الإنجليزية). 4 November 2019.

- ^ أ ب Hubbard, Ben; Kirkpatrick, David D. (19 October 2018). "Uproar Over Dissident Rattles Saudi Royal Family". The New York Times.

- ^ أ ب Alaoudh, Abdullah (19 July 2018). "Saudi Arabia's crown prince is taking the kingdom back to the Dark Ages". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "What Changes In Saudi Arabia's Political Power Mean For U.S.-Saudi Relations". NPR.org (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Smith Diwan, Kristin (22 January 2019). "Saudi Arabia Reassigns Roles within a More Centralized Monarchy". Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington.

- ^ أ ب Hubbard, Ben (14 September 2017). "Saudi Arabia Detains Critics as New Crown Prince Consolidates Power". The New York Times.

- ^ Hubbard, Ben; Kirkpatrick, David D.; Kelly, Kate; Mazzetti, Mark (11 March 2018). "Saudis Said to Use Coercion and Abuse to Seize Billions". The New York Times.

- ^ أ ب "Radical reforms in Saudi Arabia are changing the Gulf and the Arab world, Radical reforms in Saudi Arabia are changing the Gulf and the Arab world". The Economist.

- ^ أ ب Mazzetti, Mark; Hubbard, Ben (17 March 2019). "It Wasn't Just Khashoggi: A Saudi Prince's Brutal Drive to Crush Dissent". The New York Times.

- ^ Nereim, Vivian; Martin, Matthew (1 February 2018). "Saudis Raise Allowances for Some Royals after Purge". www.bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Campagna, Joel. "Saudi Arabia report: Princes, Clerics, and Censors". cpj.org (in الإنجليزية). Committee to Protect Journalists.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia says religious police must be 'gentle and humane'". The Guardian. Associated Press. 13 April 2016 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ أ ب Yee, Vivian (26 November 2019). "Saudi Arabia Is Stepping Up Crackdown on Dissent, Rights Groups Say". The New York Times.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Mahdi, Wael (24 March 2009). "New-look book fair backfires on writers". The National (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت "Saudi Book Fair Called Out for Display of Antisemitic Titles, Including Mein Kampf". Algemeiner.com.

- ^ أ ب ت "The red ink and the black: The unlikely rise of book fairs in the Gulf". The Economist. 6 July 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت Khashoggi, Jamal (3 April 2018). "By blaming 1979 for Saudi Arabia's problems, the crown prince is peddling revisionist history". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Saudi Arabia: Liberalization, Not Democratization". afsa.org.

- ^ Nolan, Leigh (May 2011). "Managing reform? Saudi Arabia and the king's dilemma" (PDF). Brookings Doha Center.

- ^ أ ب "Saudi Arabia: 420 books banned at Riyadh International Book Fair". Freemuse. 18 March 2014.

- ^ Massoglia, Anna (2 October 2019). "Saudi Arabia ramped up multi-million foreign influence operation after Khashoggi's death". OpenSecrets News. The Center for Responsive Politics.

- ^ Thebault, Reis; Mettler, Katie (24 December 2019). "Instagram influencers partied at a Saudi music festival — but no one mentioned human rights". Washington Post.

- ^ أ ب "Unshackling themselves, Unshackling themselves". The Economist.

- ^ Nereim, Vivian (15 December 2019). "Saudi Unemployment Falls to 3-Year Low While Expat Exodus Slows". www.bloomberg.com.

- ^ Dudley, Dominic. "Rising Unemployment Suggests Saudi Government Reforms Are Failing". Forbes (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت Translated quotation from The New York Times: Yee, Vivian; Kirkpatrick, David D. (5 April 2019). "Saudis Escalate Crackdown on Dissent, Arresting Nine and Risking U.S. Ire". The New York Times.

- ^ أ ب "The Saudi response to the 'Arab spring': containment and co-option". openDemocracy.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmoderation - ^ al-Rasheed, Madawi (22 January 2015). "King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia obituary". The Guardian.

- ^ Eman al-Nafjan (18 February 2011). "The Arab Revolution Saudi Update". Saudiwoman's Weblog (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Murphy, Caryle. "Will the House of Saud adapt enough to survive ... again? | The Star". thestar.com (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Census shows Kingdom's population at more than 27 million". Saudi Gazette. 24 نوفمبر 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ^ أ ب Guest Contributor (10 August 2016). "What If Saudi Arabia Collapses?". LobeLog (in الإنجليزية).

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Dozens of Saudi Arabian women drive cars on day of protest against ban". The Guardian. 26 October 2013.

- ^ Gallup (21 December 2007). "Saudi Arabia: Majorities Support Women's Rights". Gallup.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية).

- ^ Sidahmed, Mazin (26 September 2016). "Thousands of Saudis sign petition to end male guardianship of women". The Guardian.

- ^ Eman al-Nafjan. "Are we or aren't we?". Saudiwoman's Weblog (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب Ismail, Raihan. "How is MBS's consolidation of power affecting Saudi clerics in the opposition?". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب Lacroix, Stéphane. "Saudi Arabia's Muslim Brotherhood predicament". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب "Sixth of November at the Riyadh Book Fair". Saudiwoman's Weblog (in الإنجليزية). 13 March 2014.

- ^ See details in the section of this article about the 2012 fair, for instance.

- ^ Shahine, Alaa; Nereim, Vivian; Abu-Nasr, Donna. "Saudi Arabia's Great Makeover Can't Afford to Fail This Time". www.bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem. "Saudi Arabia's once-powerful conservatives silenced by reforms and repression". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Khashoggi, Jamal. "Saudi Arabia's crown prince wants to 'crush extremists.' But he's punishing the wrong people". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Batrawy, Aya (26 November 2019). "Activists: Saudi Arabia detains eight in sustained crackdown". AP NEWS.

- ^ أ ب Safi, Michael (4 November 2019). "Saudi Arabia: arrests of dissidents and torture allegations continue". The Guardian.

- ^ "Not Fair!". Saudi Jeans (in الإنجليزية). 19 September 2004.

- ^ "The Book Fair Report". Saudi Jeans (in الإنجليزية). 30 September 2004.

- ^ أ ب ت "Saudi Jeans: Let's Meet and Talk". 15 November 2007. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007.

- ^ "Riyadh International Book Fair". Khaled rambles. 17 February 2006.

- ^ Asharq Al-Awsat. "Saudi Arabia: Copies of Girls of Riyadh Novel Mysteriously Disappear from Book Fair". eng-archive.aawsat.com (in الإنجليزية). (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source)

- ^ أ ب ت "Saudi Arabia: 2007 Riyadh International Book Fair, Ahmadinejad's Visit to the Kingdom, and More". Global Voices (in الإنجليزية). 7 March 2007.

- ^ Arabia, Crossroads (21 March 2007). "Riyadh Book Fair off to Quiet Start". Archived from the original on 21 March 2007.

- ^ "معرض الرياض الدولي للكتاب 2008". 14 March 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. (official schedule; not an independent source)

- ^ Al-Omran, Ahmed. "Some of the 'Less Boring' Saudi Wikileaks Cables". MidEastPosts.com.

- ^ "New Audiences Reached at Riyadh International Book Fair". Wikileaks. 2008.

- ^ "Riyadh-Book-Fair". KSA Ministry of Culture and Information. 16 December 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2009. (not an independent source)

- ^ أ ب ت ث "High prices, Hai'a dampen spirits at Riyadh Book Fair". Saudi Gazette. 27 May 2009. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Hawari, Walaa; Al-Dosary, Shiekha (11 March 2009). "Women's Issues in the Middle East: Saudi Arabia: Frustrating experience". Women's Issues in the Middle East (apparently reprinting an Arab News report). Arab News (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source).

- ^ أ ب "The tanjara: Religious[sic] police and censorship cause discontent at Riyadh book fair". the tanjara. 10 March 2009.

- ^ Aside from a blog,[88] only domestic (and thus Saudi-government-controlled) media give names of all three men;[86][87] Associated Press says three men but gives one name;[24] CNN says only two were arrested, but cite the Saudi reports.[21] A reprinting of a domestic media article[87] carries a great deal of detail on the incident, including what appear to be interviews with the participants. It contradicts another source on whether the journalist was trying to give books to her colleagues, and had to pass them via a male security guard,[87] or the male writers had bought books and passed them to her via a male security guard.[86] All the accounts seem to be by or based upon domestic media.

- ^ "Abdo Khal: International Prize for Arabic Fiction". www.arabicfiction.org.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Saudi Publisher Booted From Riyadh International Book Fair". & Arablit (in الإنجليزية). 12 March 2014.

- ^ "If You're in the KSA: The Riyadh International Book Fair". & Arablit (in الإنجليزية). 20 February 2010.

- ^ "Riyadh-Book-Fair". Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia. 11 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Original Ministry of Culture official schedule, not an independent source

- ^ "Riyadh International Book Fair 2010, let's try this again". Khaled rambles. 3 March 2010. (Site unavailable on the March 1st, with the invite-only opening day on the 2nd)

- ^ "But is it fiction?". al-bab.com (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Calderbank, Tony. "One Arabic-English translator shares his experience". www.britishcouncil.org (in الإنجليزية). British Council.

- ^ "Saudi writers find voice depicting closed society". dawn.com (in الإنجليزية). 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia". freedomhouse.org (in الإنجليزية). 12 January 2012.

- ^ أ ب ت Royston, Steve. "Sharp Divides Emerge over Saudi Reforms". MidEast Posts.

- ^ أ ب Wagner, Rob L. "Riyadh Book Fair Debacle is Nothing More Than Theater". MidEast Posts. (Not an independent source; Rob L. Wagner, the author, was an editor at Saudi-government-controlled Arab News at the time of writing, and has long been employed in posts under Saudi government control.)

- ^ "Saudi hardliners disrupt book fair". Ahram Online (in الإنجليزية). Agence France-Presse.

- ^ "Book Fair Updates: Riyadh Disrupted by Ultraconservatives, Report from Casablanca". & Arablit (in الإنجليزية). 3 March 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Saudi hardliners disrupt book fair: Witnesses". Zee News (in الإنجليزية). 3 March 2011.

- ^ Whitaker, Brian (3 March 2011). "Thuggery at Saudi book fair". al-bab.com (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Riyadh". Khaled rambles.

- ^ "البرد يزور معرض الكتاب". Al Riyadh جريدة الرياض. 2011-03-12. (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source)

- ^ Arabia, Crossroads. "Saudi Authorities Crack Down on 'Book Fair Louts'". MidEast Posts.

- ^ أ ب "(Don't) Boycott the Riyadh International Book Fair". & Arablit (in الإنجليزية). 9 March 2012.

- ^ Saad, Mohammed (29 January 2013). "Arab Publishers Association boycotts Riyadh Book Fair - Arab - Books". Ahram Online (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Controversy Even Months Before Opening of 2013 Riyadh International Book Fair". & Arablit (in الإنجليزية). 30 January 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت "Riyadh fair bans Oman writer's book". gulfnews.com (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Saudi women given unprecedented permit to attend book fairs - with men". Ahram Online (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت "Saudi Arabia bans prominent Palestinian authors from Riyadh book fair". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com.

- ^ أ ب "Saudi bans books at fair in wide-ranging crackdown". Ahram Online (in الإنجليزية). Agence France-Presse. 16 March 2014.

- ^ "No, Ambassador: It's Not 'Meddling' to Call for Free Speech in Saudi Arabia". HuffPost UK. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015.

- ^ Al-Rasheed, Madawi (13 March 2014). "Saudi officials shut down display at book fair". Al-Monitor (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب "Saudi bans books at fair in crackdown". www.emirates247.com (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب ت "KSA: Members of the Saudi Religious Police (CPVPV – The Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice) Attacks a Seminar About Destroying Monuments". Arabic Network for Human Rights Information. 9 March 2015.

- ^ أ ب "The 2015 Riyadh International Book Fair: A Mixed Bag". & Arablit (in الإنجليزية). 17 March 2015.

- ^ Whitaker, Brian. "Where literary meets military". al-bab.com (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Liberated Saudi Youth Wonder Where All the Wahhabis Have Gone". Bloomberg Businessweek.

- ^ Speyer, Lea. "Human Rights Organization: Antisemitic Literature at US-Backed Riyadh Book Fair a 'Tragedy for the Jewish People'". Algemeiner.com.

- ^ أ ب "Saudi Arabia". United States Department of State.

- ^ Speyer, Lea. "State Department Denies Knowledge of Antisemitic Material at Saudi Book Fair Attended by US Embassy Reps (Video)". Algemeiner.com.

- ^ أ ب "Saudi Arabia: Books banned, performance interrupted at book fair". Freemuse.

- ^ Alnufaie, Hanan. "Young Malaysian painter wins Saudi hearts at Riyadh Book Fair". english.alarabiya.net (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Wiesenthal Centre to Saudi Culture Minister: "We are Distressed to Discover Vicious Antisemitic Conspiracy Texts on Display at the Riyadh Book Fair"". www.wiesenthal.com.

- ^ "Saudi law professor arrested for criticising kingdom's human rights record: Report". Middle East Eye (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Fresh wave of arrests in Saudi Arabia". www.amnesty.org (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ النجار Alnajjar, أميمه Omaima (9 September 2019). "Anas al-Mazrou" (in الإنجليزية). القسط ALQST. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Wiesenthal Centre to Saudi Media Minister: "Ban Antisemitic Hate at the Riyadh International Book Fair"". www.wiesenthal.com.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Culture Announces Riyadh Book Fair Plans for 2020". About Her (in الإنجليزية). 2019-07-16. Retrieved 2019-08-06. (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source)

- ^ "Saudi Culture Ministry chooses 'Riyadh Front' as book fair's new headquarters". Arab News (in الإنجليزية). 2020-01-10. Retrieved 2020-01-11. (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source)

- ^ "Riyadh Int'l Book Fair Postponed over Coronavirus Fears". Asharq Al-awsat (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-03-06. (Saudi-government-controlled media, and thus not an independent source)