تاريخ جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية

جزء من سلسلة عن |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| تاريخ جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

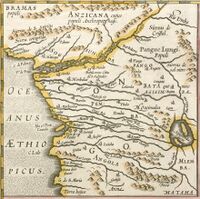

الحقبة الأولى. الأقزام أول من عُرف من سكان المنطقة المعروفة حاليًا باسم جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية. وقد عاشوا فيها منذ عصور ماقبل التاريخ. وقبل 2000 سنة على الأقل هاجرت جماعات من أجزاء أخرى من إفريقيا، إلى هذه المنطقة. ومنذ القرن الثامن الميلادي نشأت حضارات متطورة في الجزء الجنوبي من الكونغو الديمقراطية. وفي القرن الخامس عشر وربما قبله نشأت عدة دول منفصلة في منطقة السافانا جنوبي منطقة الغابات المطيرة، أكبرها ممالك الكونغو والكوبا واللوبا واللواندا. وفي القرن السابع عشر أو الثامن عشر الميلاديين، نشأت ممالك أخرى قرب الحدود الشرقية للبلاد. وكانت تقيم علاقات تجارية مع سكان السواحل الشرقية والغربية.

Kingdom of Kongo controlled much of western and central Africa including what is now the western portion of the DR Congo between the 14th and the early 19th centuries. At its peak it had many as 500,000 people, and its capital was known as Mbanza-Kongo (south of Matadi, in modern-day Angola). In the late 15th century, Portuguese sailors arrived in the Kingdom of Kongo, and this led to a period of great prosperity and consolidation, with the king's power being founded on Portuguese trade. King Afonso I (1506–1543) had raids carried out on neighboring districts in response to Portuguese requests for slaves. After his death, the kingdom underwent a deep crisis.[1]

The Atlantic slave trade occurred from approximately 1500 to 1850, with the entire west coast of Africa targeted, but the region around the mouth of the Congo suffered the most intensive enslavement. Over a strip of coastline about 400 kilometres (250 mi) long, about 4 million people were enslaved and sent across the Atlantic to sugar plantations in Brazil, the US and the Caribbean. From 1780 onwards, there was a higher demand for slaves in the US which led to more people being enslaved. By 1780, more than 15,000 people were shipped annually from the Loango Coast, north of the Congo.[1]

In 1870, explorer Henry Morton Stanley arrived in and explored what is now the DR Congo. Belgian colonization of DR Congo began in 1885 when King Leopold II founded and ruled the Congo Free State. However, de facto control of such a huge area took decades to achieve. Many outposts were built to extend the power of the state over such a vast territory. In 1885, the Force Publique was set up, a colonial army with white officers and black soldiers. In 1886, Leopold made Camille Jansen the first Belgian governor-general of Congo. Over the late 19th century, various Christian (including Catholic and Protestant) missionaries arrived intending to convert the local population. A railway between Matadi and Stanley Pool was built in the 1890s.[1] Reports of widespread murder, torture, and other abuses in the rubber plantations led to international and Belgian outrage and the Belgian government transferred control of the region from Leopold II and established the Belgian Congo in 1908.

Following unrest, Belgium granted Congo independence in June 1960. However, the Congo remained unstable, leading to the Congo Crisis, where the regional governments of Katanga and South Kasai attempted to gain independence with Belgian support. Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba tried to suppress secession with the aid of the Soviet Union as part of the Cold War, causing the United States to support a coup led by Colonel Joseph Mobutu in September 1960. Lumumba was handed over to the Katangan government and executed in January 1961. The successionist movements were later defeated by the Congolese government as were the Soviet-backed Simba rebels. Following the end of the Congo Crisis in 1965, Joseph Kasa-Vubu was deposed and Mobutu seized complete power of the country and later renamed it Zaire. He sought to Africanize the country, changing his own name to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, and demanded that African citizens change their Western names to traditional African names. Mobutu sought to repress any opposition to his rule, which he successfully did throughout the 1980s. However, with his regime weakened in the 1990s, Mobutu was forced to agree to a power-sharing government with the opposition party. Mobutu remained the head of state and promised elections within the next two years that never took place.

During the First Congo War, Rwanda invaded Zaire, in which Mobutu lost his power during this process. In 1997, Laurent-Désiré Kabila took power and renamed the country the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Afterward, the Second Congo War broke out, resulting in a regional war in which many different African nations took part and in which millions of people were killed or displaced. Kabila was assassinated by his bodyguard in 2001, and his son, Joseph, succeeded him and was later elected president by the Congolese government in 2006. Joseph Kabila quickly sought peace. Foreign soldiers remained in the Congo for a few years and a power-sharing government between Joseph Kabila and the opposition party was set up. Joseph Kabila later resumed complete control over the Congo and was re-elected in a disputed election in 2011. In 2018, Félix Tshisekedi was elected president; in the first peaceful transfer of power since independence.[2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ المبكر

The area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo was populated as early as 80,000 years ago, as shown by the 1988 discovery of the Semliki harpoon at Katanda, one of the oldest barbed harpoons ever found, which is believed to have been used to catch giant river catfish.[3][4] During its recorded history, the area has also been known as Congo, Congo Free State, Belgian Congo, and Zaire.

The Kingdom of Kongo existed from the 14th to the early 19th century. Until the arrival of the Portuguese it was the dominant force in the region along with the Kingdom of Luba, the Kingdom of Lunda, the Mongo people and the Anziku Kingdom.

الحكم الاستعماري

دولة الكونغو الحرة (1885–1908)

منذ عام 1482م بدأ البحارة البرتغاليون ينزلون عند مصب نهر الكونغو، وما لبثت البرتغال أن أقامت علاقات دبلوماسية مع مملكة الكونغو، التي كانت تحكم المناطق الساحلية. وفي أواخر القرن الخامس عشر الميلادي، قام ممثلون للمملكة بزيارة البرتغال والفاتيكان مقر رئاسة الكنيسة الكاثوليكية. وبعد قليل اتخذت مملكة الكونغو النصرانية الكاثوليكية ديانة رسمية لها، ونُصِّب عدد كبير من مواطني الكونغو كهنة كاثوليكيين.

في أوائل القرن السادس عشر الميلادي بدأ البرتغاليون يسترقَّون الأفارقة، واشتروا أعداداً كبيرة من الرقيق من حكام المملكة. وبعد قليل جاراهم الأوروبيون الآخرون في تجارة الرقيق. وخلال الفترة من أوائل القرن السادس عشر الميلادي وحتى أواخر القرن الثامن عشر، تم استرقاق مئات الآلاف من سكان منطقة الكونغو الديمقراطية، أرسل معظمهم رقيقًا إلى الأمريكتين الشمالية والجنوبية.

وفي عام 1876م قام هنري. م. ستانلي، وهو مكتشف بريطاني، بعبور الكونغو الديمقراطية من الشرق إلى الغرب. وقام مكتشفون آخرون بعبور المنطقة في الوقت نفسه تقريبًا. وقد وفرت هذه الكشوف للأوروبيين والأمريكيين أول معلومات مفصلة عن المنطقة المعروفة حاليا باسم الكونغو الديمقراطية.

الحكم البلجيكي

في عام 1878م كلف ليوبولد الثاني ملك بلجيكا المكتشف ستانلي، بإنشاء مراكز حراسة بلجيكية متقدمة على نهر الكونغو. وعن طريق جهود دبلوماسية حصيفة، استطاع ليوبولد إقناع القادة الأوروبيين الآخرين بالاعتراف به حاكمًا على مايعرف الآن بالكونغو الديمقراطية. نص في هذا الاعتراف على أن ليوبولد نفسه وليس الحكومة البلجيكية، هو حاكم الكونغو الديمقراطية. وأصبح القطر مستعمرة شخصية لليوبولد في الأول من يوليو عام 1885م وأطلق عليه اسم دولة الكونغو الحرة.

عانى شعب دولة الكونغو الحرة كثيرًا، تحت وطأة حكم ليوبولد؛ حيث كان عملاء الملك يعاملون السكان بقسوة، ويرغمونهم على العمل لساعات طويلة في جمع المطاط من الغابات، وبناء خط للسكك الحديدية، مما أدى إلى وفاة الكثيرين منهم تحت وطأة المعاملة القاسية.

أثارت طريقة حكم ليوبولد الجائرة كثيرًا من الاحتجاجات خاصة من قِبَل إنجلترا، والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية، مما أدى إلى استيلاء الحكومة البلجيكية على الحكم في دولة الكونغو الحرة من ليوبولد في 1908م وأعادت تسميته باسم الكونغو البلجيكي، وقد كان حكم البلجيكيين للبلاد قاسيًا أيضًا في كثير من الأحيان، ولكنها عملت على تحسين ظروف العمل والمعيشة للمواطنين نوعًا ما.

وبحلول العشرينيات من القرن العشرين كانت الحكومة البلجيكــية، تحصــل على ثــروات طائلة من اســتغلال النحاس والماس والذهب وزيت النخيل وغيرها من الموارد في الكونغو. وفي الثلاثينيات أدى الكساد الاقتصادي العالمي الكبير إلى شل اقتصاد المستعمرة، نتيجة للهبوط الحاد في أسعار منتجاتها وانخفاض الطلب عليها. وفي 1940م دخلت بلجيكا الحرب العالمية الثانية إلى جانب الحلفاء، حيث أسهم الكونغو البلجيكي في إمداد الحلفاء بمواد خام ذات قيمة عالية.

وبانتهاء الحرب العالمية الثانية في 1945م، عاود اقتصاد الكونغو البلجيكي تطوره السريع مع ارتفاع قيمة صادراته، وفي الوقت نفسه بدأ البلجيكيون في بذل جهود لتحسين مستوى التعليم والعناية الطبية لسكان المستعمرة، ولكنهم أصروا على رفضهم إعطاء هؤلاء السكان أي دور في إدارة شؤون الحكم.

الاستقلال

مقالة مفصلة: أزمة الكونغو

مقالة مفصلة: أزمة الكونغو

منذ الخمسينيات بدأ كثير من السكان الأفارقة في الكونغو البلجيكي بالدعوة للاستقلال عن بلجيكا. وفي 1957م سمحت الحكومة البلجيكية لسكان المستعمرة بانتخاب ممثليهم في بعض مجالس المدن، ولكن ذلك لم يوقف المطالبة بالاستقلال. وفي 1959 اندلعت الثورات والاضطرابات ضد الحكم البلجيكي. وفي 30 يونيو 1960م منحت بلجيكا الاستقلال للمستعمرة، وأطلق عليها اسم الكونغو.

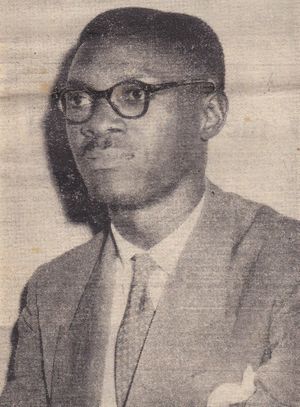

وفي أول انتخابات تجرى في البلاد قبل نحو شهر من الاستقلال، فازت تسعة أحزاب سياسية بمقاعد في المجلس التشريعي الوطني، ولكن لم يحصل أي منها على الأغلبية بالمجلس، وقد أدى توزيع أصوات الناخبين بهذا الشكل إلى إضعاف سلطة ووحدة الحكومة، وكحل وسط عشية الاستقلال، اتفق اثنان من الزعماء على اقتسام السلطة، حيث أصبح جوزيف كساڤوبو رئيسًا للجمهورية، وباتريس لومومبا رئيسًا للوزراء.

في عام 1959، پاتريس لومومبا زعيم الحركة الوطنية الكونغولية فاز بأول إنتخابات نيابية حرة. ولذلك عُين أول رئيس وزراء للدولة المستقلة، بينما منصب رئيس الجمهورية الشرفي شغله جوسف كاساڤوبو (قائد تحالف باكونگو الموالي للإستعمار البلجيكي).

الاضطرابات الأهلية

اندلعت اضطرابات أهلية إثر الاستقلال في الكونغو، وكان الضباط البلجيكيون ما زالوا يسيطرون على الجيش، وكثير من الموظفين البلجيكيين يشغلون وظائف حكومية مهمة. وبعد خمسة أيام من الاستقلال تمرَّد جنود الجيش قرب ليوبولد فيل (الآن كنشاسا) على ضباطهم البلجيكيين، وانتشر التمرد في كل أنحاء الكونغو، وهرب معظم البلجيكيين العاملين في الحكومة من البلاد.

بعد الإستقلال مباشرة قامت بلجيكا بمساندة حركات انفصالية في إقليمي كاتنگا الغني بالبترول (بقيادة مويز تشومبي) وجنوب كاساي. ثم مالبث أن اندلع خلاف بين كاسافوبو ولومومبا أفضى إلى أن طرد الأول الثاني من منصبه. وفي ظروف غامضة أجبرت بلجيكا طائرة مقلة للومومبا، داخل الكونغو، على الهبوط ثم سلمته إلى مويز تشومبي الذي قتله في 17 يناير 1961، ثم إلتهم كبده للتأكد من موته. بمصرع لومومبا سقطت البلاد في دوامة الفوضى كاسافوبو الموالي لبلجيكا لمدة خمس سنوات. ثم قام الجنرال موبوتو بإنقلاب عليه في 1965.

في 30 يونيو 1967، أجبرت الجزائر طائرة مقلة لتشومبي علي الهبوط في الجزائر حيث ألقي القبض عليه ثم توفى في ظروف غامضة قيل أنها نوبة قلبية.

وفي يوليو عام 1960م انفصلت مقاطعة كاتنگا (الآن إقليم شابا)، عن الدولة الجديدة وأعلنت نفسها دولة مستقلة. وقد كانت هذه المقاطعة المنتجة للنحاس في جنوبي البلاد أغنى منطقة في القطر. وحذت مقاطعة كاساي المنتجة للماس حذو كاتنغا في شهر أغسطس. وفي سبتمبر التالي عزل رئيس الجمهورية كازافوبو رئيس الوزراء لومومبا، الذي سُجن ثم اغتيل في 1961م. وبعد ذلك قام مؤيدو لومومبا بتكوين حكومة منافسة لحكومة كازافوبو، وأعلنوا أنها الحكومة الشرعية للبلاد.

ونتيجة طبيعية لهذه الخلافات اندلع القتال بين الفئات المتنافسة، وأعقب ذلك إرسال قوات من الأمم المتحدة في 1960م للبلاد؛ لإعادة الأمن والنظام بدعوة من الحكومة. وفي أغسطس عام 1961م توصلت الفئات المتنافسة إلى حل وسط، اتفقوا بموجبه على توحيد البلاد ماعدا مقاطعة كاتنغا، وعُين سيريل أدولا رئيسًا للوزراء في الحكومة الجديدة.

وفي يناير عام 1963م تمكنت قوات الأمم المتحدة من إنهاء انفصال كاتنغا، وهرب كثير من المتمردين إلى أنجولا المجاورة. وعلى إثر إنهاء الانفصال، انسحبت قوات الأمم المتحدة من الكونغو في يونيو عام 1964م. وفي يوليو من العام نفسه حدثت تسوية سياسية، تدعو إلى الدهشة، أصبح بموجبها مويس تشومبي الذي قاد انفصال كاتنغا رئيسًا لوزراء الدولة الموحدة، وفي الوقت نفسه تقريبًا ضربت البلاد موجة جديدة من الاضطرابات والثورات، تمكنت الحكومة من إخمادها بمساعدة المرتزقة البيض بنهاية عام 1965م.

وفي مارس 1965م أُجريت الانتخابات العامة في البلاد، وفاز بها ائتلاف هش بقيادة مويس تشومبي، ولكن الائتلاف مالبث أن تفكك، وأدت الخلافات بين الزعماء السياسيين إلى تعطيل أعمال الحكومة، مما أدى إلى استيلاء الجيش على مقاليد الحكم في نوفمبر من العام نفسه، وعُين الجنرال جوزيف ديزيريه موبوتو رئيسًا للجمهورية.

زائير (1965–1997)

تسببت الاضطرابات الأهلية التي سادت البلاد خلال أوائل الستينيات، في إحداث أضرار شديدة باقتصاد الكونغو، كما أدى القتال بين الفئات المختلفة للشعب، إلى شعور بالمرارة وانقسامات حادة بين هذه الفئات. ولمجابهة ذلك اتخذ الرئيس موبوتو بعض الخطوات في محاولة لحل المشاكل التي تواجه البلاد، مثل: تكوين حكومة وطنية قوية تمكنت من بسط سيطرتها على كل البلاد، وساعدت على إنهاء القتال بين فئات الشعب، وتخفيف حدة الفوارق العرقية، التي سادت في السنوات السابقة. وقد أدى هذا إلى تحسن مطرد في الاقتصاد في أواخر الستينيات من القرن العشرين.

وقد سعى موبوتو أيضًا إلى تدعيم الأمة، بتشجيع الاعتزاز بالتراث الإفريقي، والحد من التأثير الأوروبي. وكان كثير من المدن والمعالم الطبيعية في القطر، تحمل أسماء أوروبية استبدلت بها الحكومة أسماء إفريقية. وفي عام 1971م غيرت الحكومة اسم القطر من الكونغو إلى زائير، كذلك وجهت الحكومة كل مواطنيها الأفارقة الذي يحملون أسماء أوروبية إلى أن يستبدلوا بها أسماء إفريقية، وغيَّر موبوتو نفسه اسمه من جوزيف ديزيريه موبوتو إلى موبوتو سيسي سيكو في 1972م.

التطورات الأخيرة

أدت المشاكل الناجمة عن الركود الاقتصادي والتضخم العالميين في أوائل السبعينيات من القرن العشرين، إلى مصاعب اقتصادية جديدة في زائير؛ حيث انخفضت أسعار النحاس بشكل حاد مما تسبب في نقص شديد في الإيرادات المالية للبلاد. وقد تزامن ذلك مع ارتفاع شديد في أسعار النفط والمواد الغذائية، اللذين تستوردهما زائير.

في 1977م قام ثوار كاتنغا الذين كانوا يعيشون في أنجولا بغزو زائير، للاستيلاء على مقاطعة كاتنگا السابقة، التي كانت قد أعيدت تسميتها بإقليم شابا، ولكن القوات الحكومية الزائيرية استطاعت بمساعدة قوات مغربية ومعدات حربية فرنسية هزيمة الغزاة. وعاود ثوار كاتنگا الكرَّة ثانية في 1978م، ولكن القوات الزائيرية استطاعت هزيمتهم مرة أخرى بمساعدة قوات فرنسية وبلجيكية.

في 1990م أعلن موبوتو عن خطط للإصلاحات الحكومية، وعن عزمه على السماح بحرية تشكيل أحزاب سياسية معارضة، والسماح لها بترشيح أعضائها في الانتخابات التي أجريت في 1991م. علمًا بأن كل المواطنين كانوا ملزمين في السابق بالانضمام إلى حزب الحركة الشعبية الثورية، ولم يكن يسمح لهم بانتقاد الحكومة علانية. وقد قام موبوتو أيضًا بتعيين حكومة انتقالية تضم رئيسًا للوزراء، ولكنه ظل يحتفظ بمنصب رئيس الدولة. كذلك أعلن موبوتو عن خطط لإعادة كتابة دستور زائير. وفي يونيو 1997م، اجتاحت قوات لوران كابيلا ـ المعارض الرئيسي لموبوتو ـ العاصمة كنشاسا، ونصّب نفسه رئيسًا للبلاد، التي أطلق عليها اسم جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية. هرب الرئيس موبوتو إلى المغرب وتوفي هناك، بمرض السرطان، في سبتمبر من العام نفسه.

انتظمت انتفاضة مسلحة المناطق الشرقية من البلاد ضد حكومة كابيلا، وقد وجد المتمردون دعماً كبيرًا من حكومتي رواندا وأوغندا إذ حاربت قوات الدولتين إلى جانب صفوف المتمردين. وفي الوقت نفسه تلقى كابيلا دعماً مماثلاً من أنجولا وتشاد وزمبابوي وناميبيا.وفي يوليو 1999م وقعت الكونغو وبقية الدول التي اشتركت في الصراع، عدا تشاد التي كانت قد سحبت قواتها في وقت سابق، على اتفاقية لوقف إطلاق النار. لم يوقع المتمردون على الاتفاقية، واستمر القتال المتقطع بين الطرفين المتنازعين. وفي يناير 2001م، اغتال أحد أفراد الحرس الرئاسي الرئيس كابيلا، وتولى ابن الرئيس الراحل الجنرال جوزيف كابيلا السلطة في البلاد.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحروب الأهلية (1996–2003)

حرب الكونغو الأولى (1996–97)

By 1996, tensions from the war and genocide in neighboring Rwanda had spilled over into Zaire. Rwandan Hutu militia forces (Interahamwe) who had fled Rwanda following the ascension of a Tutsi-led government had been using Hutu refugee camps in eastern Zaire as bases for incursions into Rwanda. In October 1996 Rwandan forces attacked refugee camps in the Rusizi River plain near the intersection of the Congolese, Rwandan and Burundi borders meet, scattering refugees. They took Uvira, then Bukavu, Goma and Mugunga.[5]

Hutu militia forces soon allied with the Zairian armed forces (FAZ) to launch a campaign against Congolese ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire. In turn, these Tutsis formed a militia to defend themselves against attacks. When the Zairian government began to escalate the massacres in November 1996, Tutsi militias erupted in rebellion against Mobutu.

The Tutsi militia was soon joined by various opposition groups and supported by several countries, including Rwanda and Uganda. This coalition, led by Laurent-Desire Kabila, became known as the Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL). The AFDL, now seeking the broader goal of ousting Mobutu, made significant military gains in early 1997. Various Zairean politicians who had unsuccessfully opposed the dictatorship of Mobutu for many years now saw an opportunity for them in the invasion of Zaire by two of the region's strongest military forces. Following failed peace talks between Mobutu and Kabila in May 1997, Mobutu left the country on 16 May. The AFDL entered Kinshasa unopposed a day later, and Kabila named himself president, reverting the name of the country to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He marched into Kinshasa on 20 May and consolidated power around himself and the AFDL.[6][7]

In September 1997, Mobutu died in exile in Morocco.[8]

حرب الكونغو الثانية (1998–2003)

جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية واقعة في قبضة حرب أهلية، حشدت لها قوات عسكرية من الدول المجاورة مع أوغندا ورواندا المؤيدة لحركة التمرد والتي تحتل معظم الجزء الشرقي من الدولة. أغلب الحد النهري للكونغو مع جمهورية الكونغو غير محدد (لم يتوصل إلى اتفاق حول تقسيم النهر أو جزره، باستثناء منطقة بحيرة ماليبو/ ستانلي).

فترة جوزيف كابيلا

الحكومة الانتقالية (2003–2006)

DR Congo had a transitional government in July 2003 until the election was over. A constitution was approved by voters and on 30 July 2006 the Congo held its first multi-party elections since independence in 1960. Joseph Kabila took 45% of the votes and his opponent Jean-Pierre Bemba 20%. That was the origin of a fight between the two parties from 20 to 22 August 2006 in the streets of the capital, Kinshasa. Sixteen people died before policemen and MONUC took control of the city. A new election was held on 29 October 2006, which Kabila won with 70% of the vote. Bemba has decried election "irregularities". On 6 December 2006 Joseph Kabila was sworn in as president.

نزاع كيڤو

شمال كيڤو وجنوب كيڤو، حيث تواصل القوات الديمقراطية لتحرير رواندا (FDLR) تهديد الحدود الرواندية و بانيامولنگه، فقد ساندت رواندا متمردي RCD-Goma (انظر حرب كيڤو).

Félix Tshisekedi presidency (2019–present)

On 30 December 2018 the presidential election to determine the successor to Kabila was held. On 10 January 2019, the electoral commission announced opposition candidate Félix Tshisekedi as the winner of the vote.[9] He was officially sworn in as president on 24 January 2019.[10] in the ceremony of taking of the office[11] Félix Tshisekedi appointed Vital Kamerhe as his chief of staff. In June 2020, chief of staff Vital Kamerhe was found guilty of embezzling public funds and he was sentenced to 20 years in prison.[12] However, Kamerhe was released in December 2021.[13]

The political allies of former president Joseph Kabila, who stepped down in January 2019, maintained control of key ministries, the legislature, judiciary and security services. However, President Felix Tshisekedi succeeded to strengthen his hold on power. In a series of moves, he won over more legislators, gaining the support of almost 400 out of 500 members of the National Assembly. The pro-Kabila speakers of both houses of parliament were forced out. In April 2021, the new government was formed without the supporters of Kabila.[14] President Felix Tshisekedi succeeded to oust the last remaining elements of his government who were loyal to former leader Joseph Kabila.[15] In January 2021, DRC's President Félix Tshisekedi pardoned all those convicted in the murder of Laurent-Désiré Kabila in 2001. Colonel Eddy Kapend and his co-defendants, who have been incarcerated for 15 years, were released.[16]

Continued conflicts

The inability of the state and the world's largest United Nations peacekeeping force to provide security throughout the vast country has led to the emergence of up to 120 armed groups by 2018,[17] perhaps the largest number in the world.[18][19] Armed groups are often accused of being proxies or being supported by regional governments interested in Eastern Congo's vast mineral wealth. Some[weasel words] argue that much of the lack of security by the national army is strategic on the part of the government, who let the army profit from illegal logging and mining operations in return for loyalty.[20] Different rebel groups often target civilians by ethnicity and militias often become oriented around ethnic local militias known as "Mai-Mai".[21]

Conflict in Kivu (2004–present)

Laurent Nkunda with other soldiers from RCD-Goma who were integrated into the army defected and called themselves the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP). Starting in 2004, CNDP, believed to be backed by Rwanda as a way to tackle the Hutu group Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), rebelled against the government, claiming to protect the Banyamulenge (Congolese Tutsis). In 2009, after a deal between the DRC and Rwanda, Rwandan troops entered the DRC and arrested Nkunda and were allowed to pursue FDLR militants. The CNDP signed a peace treaty with the government where its soldiers would be integrated into the national army.

In April 2012, the leader of the CNDP, Bosco Ntaganda and troops loyal to him mutinied, claiming a violation of the peace treaty and formed a rebel group, the March 23 Movement (M23), which was believed to be backed by Rwanda. On 20 November 2012, M23 took control of Goma, a provincial capital with a population of one million people.[22] The UN authorized the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB), which was the first UN peacekeeping force with a mandate to neutralize opposition rather than a defensive mandate, and the FIB quickly defeated M23. The FIB was then to fight the FDLR but were hampered by the efforts of the Congolese government, who some believe tolerate the FDLR as a counterweight to Rwandan interests.[20] Since 2017, fighters from M23, most of whom had fled into Uganda and Rwanda (both were believed to have supported them), started crossing back into DRC with the rising crisis over Kabila's extension of his term limit. DRC claimed of clashes with M23.[19][23]

After rising insecurity, President Tshisekedi declared a "state of siege" or state of emergency in North Kivu, as well as Ituri province, in the first such declaration since the country's independence. The military and police took over positions from civilian authorities and some saw it as a powerplay since the civilian officials were part of the opposition to the President. A similar declaration was avoided for South Kivu, in a move believed to avoid antagonizing armed groups with ties to regional powers such as Rwanda.[24]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Allied Democratic Forces insurgency

The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) has been waging an insurgency in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and is blamed for the Beni massacre in 2016. While the Congolese army maintains that the ADF is an Islamist insurgency, most observers feel that they are only a criminal group interested in gold mining and logging.[20][25] In March 2021, the United States claimed that the ADF was linked to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant as part of the Islamic State's Central Africa Province. By 2021, the ADF was considered the deadliest of the many armed groups in the east of the country.[26]

Ethnic Mai Mai factions

Ethnic conflict in Kivu has often involved the Congolese Tutsis known as Banyamulenge, a cattle herding group of Rwandan origin derided as outsiders, and other ethnic groups who consider themselves indigenous. Additionally, neighboring Burundi and Rwanda, who have a thorny relationship, are accused of being involved, with Rwanda accused of training Burundi rebels who have joined with Mai Mai against the Banyamulenge and the Banyamulenge is accused of harboring the RNC, a Rwandan opposition group supported by Burundi.[27] In June 2017, the group, mostly based in South Kivu, called the National People's Coalition for the Sovereignty of Congo (CNPSC) led by William Yakutumba was formed and became the strongest rebel group in the east, even briefly capturing a few strategic towns.[28] The rebel group is one of three alliances of various Mai-Mai militias[29] and has been referred to as the Alliance of Article 64, a reference to Article 64 of the constitution, which says the people have an obligation to fight the efforts of those who seek to take power by force, in reference to President Kabila.[30] Bembe warlord Yakutumba's Mai-Mai Yakutumba is the largest component of the CNPSC and has had friction with the Congolese Tutsis who often make up commanders in army units.[29] In May 2019, Banyamulenge fighters killed a Banyindu traditional chief, Kawaza Nyakwana. Later in 2019, a coalition of militias from the Bembe, Bafuliru and Banyindu are estimated to have burnt more than 100, mostly Banyamulenge, villages and stole tens of thousands of cattle from the largely cattle-herding Banyamulenge. About 200,000 people fled their homes.[27]

Clashes between Hutu militias and militias of other ethnic groups has also been prominent. In 2012, the Congolese army in its attempt to crush the Rwandan backed and Tutsi-dominated CNDP and M23 rebels, empowered and used Hutu groups such as the FDLR and a Hutu dominated Maï Maï Nyatura as proxies in its fight. The Nyatura and FDLR even arbitrarily executed up to 264 mostly Tembo civilians in 2012.[31] In 2015, the army then launched an offensive against the FDLR militia.[32] The FDLR and Nyatura[33] were accused of killing Nande people[32] and of burning their houses.[34] The Nande-dominate UPDI militia, a Nande militia called Mai-Mai Mazembe[35] and a militia dominated by Nyanga people, the "Nduma Defense of Congo" (NDC), also called Maï-Maï Sheka and led by Gédéon Kyungu Mutanga,[36] are accused of attacking Hutus.[37] In North Kivu, in 2017, an alliance of Mai-Mai groups called the National Movement of Revolutionaries (MNR) began attacks in June 2017[38] includes Nande Mai-Mai leaders from groups such as Corps du Christ and Mai-Mai Mazembe.[29] Another alliance of Mai-Mai groups is CMC which brings together Hutu militia Nyatura[29] and are active along the border between North Kivu and South Kivu.[39] In September 2019, the army declared it had killed Sylvestre Mudacumura, head of the FDLR,[40] and in November that year the army declared it had killed Juvenal Musabimana, who had led a splinter group of the FDLR.[41]

Conflict in Katanga

In Northern Katanga Province starting in 2013, the Pygmy Batwa people,[أ] whom the Luba people often exploit and allegedly enslave,[43] rose up into militias, such as the "Perci" militia, and attacked Luba villages.[18] A Luba militia known as "Elements" or "Elema" attacked back, notably killing at least 30 people in the "Vumilia 1" displaced people camp in April 2015. Since the start of the conflict, hundreds have been killed and tens of thousands have been displaced from their homes.[43] The weapons used in the conflict are often arrows and axes, rather than guns.[18]

Elema also began fighting the government mainly with machetes, bows and arrows in Congo's Haut Katanga and Tanganyika provinces. The government forces fought alongside a tribe known as the Abatembo and targeting civilians of the Luba and the Tabwa tribes who were believed to be sympathetic to the Elema.[44]

Conflict in Kasai

In the Kasaï-Central province, starting in 2016, the largely Luba Kamwina Nsapu militia led by Kamwina Nsapu attacked state institutions. The leader was killed by authorities in August 2016 and the militia reportedly took revenge by attacking civilians. By June 2017, more than 3,300 people had been killed and 20 villages have been completely destroyed, half of them by government troops.[45] The militia has expanded to the neighboring Kasai-Oriental area, Kasaï and Lomami.[46]

The UN discovered dozens of mass graves. There was an ethnic nature to the conflict with the rebels being mostly Luba and Lulua and have selectively killed non-Luba people while the government allied militia, the Bana Mura, constituting people from the Chokwe, Pende, and Tetela, have committed ethnically motivated attacks against the Luba and Lulua.[47]

Conflict in Ituri

The Ituri conflict in the Ituri region of the north-eastern DRC involved fighting between the agriculturalist Lendu and pastoralist Hema ethnic groups, who together made up around 40% of Ituri's population, with other groups including the Ndo-Okebo and the Nyali.[48] During Belgian rule, the Hema were given privileged positions over the Lendu while long time leader Mobutu Sese Seko also favored the Hema.[49] While "Ituri conflict" often refers to the major fighting from 1999 to 2003, fighting has existed before and continues since that time. During the Second Congolese Civil War, Ituri was considered the most violent region.[49] An agricultural and religious group from the Lendu people known as the "Cooperative for the Development of Congo" or CODECO allegedly reemerged as a militia in 2017[49] and began attacking the Hema as well as the Alur people to control the resources in the region, with the Ndo-Okebo and the Nyali also involved in the violence.[50] After disagreements over negotiating with the government and the killing of CODECO's leader, Ngudjolo Duduko Justin, in March 2020, the group splintered and violence spread into new areas.[50][51] In late 2020, CODECO briefly held the capital of the province, Bunia, but retreated.[52] In June 2019, attacks by CODECO led to 240 people being killed and more than 300,000 people fleeing.[53][50]

The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), mostly active in North and South Kivu has also been involved in Ituri province. President Tshisekedi declared a "state of siege" or state of emergency in the province in May 2021 to tackle ADF. However, ADF killed 57 civilians in one attack in the same month in one of its deadliest single attacks.[26] 30 people were massacred in September 2021 by the ADF.[54] The President is accused of promoting former rebel leaders and generals accused of war crimes to be in charge of the province.[55]

Conflict in the Northwest

Dongo Conflict

In October 2009 a conflict started in Dongo, Sud-Ubangi District where clashes had broken out over access to fishing ponds.

Yumbi Massacre (2018)

Nearly 900 people were killed between 16 and 17 December 2018 around Yumbi, a few weeks before the Presidential election, when mostly those of the Batende tribe massacred mostly those of the Banunu tribe. About 16,000 fled to neighboring Republic of the Congo. It was alleged that it was a carefully planned massacre, involving elements of the national military.[56]

أسماء سابقة لمدن

انظر أيضاً

- تاريخ أفريقيا

- قائمة رؤوس دولة جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية

- قائمة رؤوس حكومة جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية

- سياسة جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية

- Timeline of Kinshasa

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ Opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi sworn in as DR Congo president. Al Jazeera. Published 24 January 2019.[التحقق مطلوب]

- ^ "Katanda Bone Harpoon Point | the Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program". Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ^ Yellen, John E. (1998). "Barbed Bone Points: Tradition and Continuity in Saharan and Sub-Saharan Africa". African Archaeological Review. 15 (3): 173–198. doi:10.1023/A:1021659928822. S2CID 128432105.

- ^ Jason Stearns (2012). Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa. PublicAffairs. p. 23. ISBN 978-1610391597 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Capture of Zaire's capital complete". CNN. 18 May 1997.

- ^ "Zaire Chooses Confusing New Name". The Spokesman-Review. May 20, 1997.

- ^ "Mobutu dies in exile in Morocco". CNN. 7 September 1997.

- ^ "Surprise Winner of Congolese Election Is An Opposition Leader". NPR.org. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "REFILE-Opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi sworn in as Congo president". Reuters. 2019-01-24. Archived from the original on 2019-01-25.

- ^ "DR Congo: Felix Tshisekedi Appoints Vital Kamerhe Chief of Staff".

- ^ "DR Congo court gives 20-year sentence to president's chief of staff Kamerhe for graft". 20 June 2020.

- ^ "DRC: Under what conditions has Vital Kamerhe been released?". The Africa Report.com. 7 December 2021.

- ^ "DR Congo names new cabinet, cements president's power".

- ^ "Felix Tshisekedi's Newly-Independent Agenda for the DRC: Modernizer or Strongman 2.0?". 26 May 2021.

- ^ "DRC : Tshisekedi pardons those convicted in the killing of Laurent-Désiré Kabila". The Africa Report.com. 5 January 2021.

- ^ "Thousands Flee Across Congo's Borders After Violence in East Rages". Bloomberg. 30 January 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت "In Congo, Wars Are Small and Chaos Is Endless". The New York Times. 30 April 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ أ ب "Congo Warns Return of M23 Rebels in East Could Block Vote". Bloomberg. 3 February 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت "UN peacekeeping in Congo Never-ending mission". The Economist. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "DRC: Thousands flee amid surge in 'horrific violence'". Al Jazeera. 30 April 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ "Goma: M23 rebels capture DR Congo city". BBC News. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Congo says M23 fighters captured downed air crew". Reuters. 31 January 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "Is President Tshisekedi's 'state of siege' a cover-up?". Deutsche Welle. 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "At least 40 killed in latest DR Congo massacre". Al Jazeera. 27 May 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ أ ب "ADF rebels killed 57 civilians in DR Congo's Ituri region: UN". Al Jazeera. 4 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ أ ب "In eastern Congo, a local conflict flares as regional tensions rise". The New Humanitarian. 28 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Eastern Congo rebels aim to march on Kinshasa: spokesman". Reuters. 29 September 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Inside the Congolese army's campaign of rape and looting in South Kivu". Irinnews. 18 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Heavy Fighting in Eastern DR Congo, Threats to Civilians Increase". Human Rights Watch. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Who are the Nyatura rebels?". IBT. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ أ ب "At least 21 Hutus killed in 'alarming' east Congo violence: UN". Reuters. 8 February 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Armed groups in eastern DRC". Irin news. 31 October 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "DRC: Rebels kill at least 10 in troubled eastern region". Al Jazeera. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Congo rebels kill at least 8 civilians in mounting ethnic violence". Reuters. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "27 killed in DRC after Maï-Maï fighters target Hutu civilians in North Kivu". International Business Times. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "DR Congo militia attack kills dozens in eastern region". Al Jazeera. 28 November 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Rebellion fears grow in eastern Congo". Irinnews. 31 October 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Sud-Kivu : Les miliciens envahissent les localités abandonnées par l'armée à Kalehe". Actualité (in الفرنسية). 2 October 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Rwandan Hutu militia commander killed in Congo, army says". Reuters. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Congo army kills leader of splinter Hutu militia group". Reuters. 10 November 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Democratic Republic of the Congo – Batwa and Bambuti". Minority Rights Group International.

- ^ أ ب "DR Congo: Ethnic Militias Attack Civilians in Katanga". Human Rights Watch. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Refugees reaching Zambia accuse DRC troops of killing civilians -U.N". Reuters. 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "DR Congo Kasai conflict: 'Thousands dead' in violence". BBC News. 20 June 2017.

- ^ "DRC's Kasai-Oriental province requires emergency assistance 600,000 says UN". International Business Times. 8 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ Wambua, Catherine (23 January 2018). "DRC aid workers in record appeal for Kasai conflict victims: More than 10 million people in central Democratic Republic of the Congo's Kasai region will need aid in 2018, NGOs warn, in the largest funding appeal in country's history". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Local Context – Armed Political Groups". Human Rights Watch. 22 January 2003. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت "Mystery militia sows fear – and confusion – in Congo's long-suffering Ituri". The New Humanitarian. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت "UN: 1,300 civilians killed in DRC violence, half a million flee". Al Jazeera. 8 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Rebel splits and failed peace talks drive new violence in Congo's Ituri". The New Humanitarian. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Congo army says it killed 33 militiaman in days of intense fighting". Reuters. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Survivors recall horror of Congo ethnic attacks". Reuters. 18 June 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "At least 30 dead in DR Congo massacre blamed on ADF jihadists". Africanews (in الإنجليزية). 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ Tampa, Vava (2022-01-10). "As violence in the Congo escalates, thousands are in effect being held hostage". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- ^ "'Along the Main Road You See the Graves': U.N. Says Hundreds Killed in Congo". The New York Times. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

ببليوگرافيا

- Turner, Thomas (2007). The Congo Wars: Conflict, Myth, and Reality (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-688-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Freund, Bill (1998). The Making of Contemporary Africa: The Development of African Society since 1800 (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-69872-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Borstelmann, Thomas (1993). Apartheid, Colonialism, and the Cold War: the United States and Southern Africa, 1945–1952. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507942-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

وصلات خارجية

- "Reforming the Heart of Darkness" Concerning the Congo under Léopold II

- BBC, Country profile: Democratic Republic of Congo

- BBC, DR Congo: Key facts

- BBC, Q&A: DR Congo conflict

- Timeline: Democratic Republic of Congo

- BBC, In pictures: Congo crisis

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج تمحيص الحقائق from September 2019

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تمحيص حقائق

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from November 2022

- CS1 maint: ref duplicates default

- تاريخ جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية

- تاريخ وسط أفريقيا

- تاريخ أفريقيا حسب البلد