نظام المعدنين

نظام المعدنين Bimetallism [أ] هو معيار نقدي تُعرف فيه قيمة الوحدة النقدية على أنها مكافئة لكميات معينة من معادن، عادة الذهب والفضة، مما يخلق سعرًا ثابتًا للتبادل بينهما. [3]

لأغراض علمية ، يتم تمييز المعادن ثنائية المعدن "المناسبة" في بعض الأحيان على أنها تسمح بأن يكون كل من النقود الذهبية والفضية مناقصة قانونية بكميات غير محدودة وأن الذهب والفضة قد يتم صياغتهما بواسطة دار سك العملة الحكومية بكميات غير محدودة. [4] هذا يميزها عن ثنائية المعدن "الأعرج"، حيث يعتبر كل من الذهب والفضة مناقصة قانونية ولكن يتم صياغتها بحرية واحدة فقط (على سبيل المثال، أموال فرنسا وألمانيا والولايات المتحدة بعد عام 1873)، ومن ثنائية المعدنين "التجارة"، حيث تُصنَّع المعادن بحرية، لكن واحدًا فقط هو العطاء القانوني والآخر يستخدم "كأموال تجارية" (على سبيل المثال معظم الأموال في أوروبا الغربية من القرنين الثالث عشر والثامن عشر). يميز الاقتصاديون أيضًا بين المعدنين القانونيين، حيث يضمن القانون هذه الشروط ، والمعدنية الفعلية، حيث يتم تداول العملات الذهبية والفضية بسعر صرف ثابت.

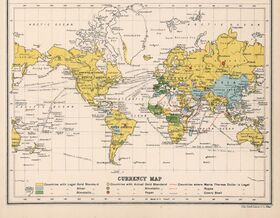

في القرن التاسع عشر ، كان هناك قدر كبير من النقاش الأكاديمي والجدل السياسي بشأن استخدام المعادن ثنائية المعدن بدلاً من المعيار الذهبي أو الفضي ( أحادية المعدن ). كان الهدف من المعدنين هو زيادة المعروض من النقود ، واستقرار الأسعار ، وتسهيل تحديد أسعار الصرف. [5] جادل بعض العلماء بأن نظام الفلزات المعدنية غير مستقر بطبيعته بسبب قانون كريشام، وأن استبداله بمعيار قياسي معدني أمر لا مفر منه. ادعى علماء آخرون أنه في الممارسة العملية كان للمعادن الثباتية تأثير استقرار على الاقتصاديات. أصبح الجدل موضع نقاش إلى حد كبير بعد التقدم التكنولوجي وزادت كل من جنوب أفريقيا وهروع الكلوندايك إلى الذهب المعروض من الذهب في التداول في نهاية القرن، مما أنهى معظم الضغط السياسي من أجل زيادة استخدام الفضة. وقد أصبحت أمراً أكاديمياً تماماً بعد صدمة نيكسون سنة 1971، التي من حينها أصبحت جميع العملات في العالم تعمل تتصرف تقريباً النقود الورقية عائمة حـُر، لا صلة له بقيمة الفضة أو الذهب. ومع ذلك، لا يزال الأكاديميون يناقشون بشكل غير حاسم الاستخدام النسبي للمعايير المعدنية. [ب]

الاجتراحات التاريخية

من القرن السابع قبل الميلاد، من المعروف أن آسيا الصغرى ، وخاصة في منطقتي ليديا وإيونيا ، صنعت عملة معدنية قائمة على الإلكتروم ، وهي مادة طبيعية تحدث تسمى الإلكتروم ، وهي مزيج متغير من الذهب والفضة (بحوالي 54 ٪ من الذهب و 44 ٪ من الفضة). قبل كروسوس ، كان والده ألياتس قد بدأ بالفعل في سك أنواع مختلفة من العملات المعدنية غير الموحدة. كانوا قيد الاستخدام في ليديا والمناطق المحيطة بها لمدة 80 عامًا تقريبًا. عدم القدرة على التنبؤ بتكوينها يعني ضمنا أن لها قيمة متغيرة يصعب تحديدها ، مما يعوق تطورها إلى حد كبير.

الكروسيات

كروسوس (حكم من عام 560 إلى 566 ق.م.) ، ملك ليديا ، الذي أصبح مرتبطًا بثروة كبيرة. وينسب كرويسوس بإصدار كروسيد ، أول عملات ذهبية حقيقية بنقاء موحد.

ذكر هيرودوت الإبداع الذي قام به الليديون:[1]

"على حد علمنا، فإنهم [الليديون] كانوا أول من استخدم العملات الذهبية والفضية، وأول من باع السلع بالقطاعي"

— هيرودوت، I94[1]

العملات الأخمينية

تبع ذلك العديد من النظم القديمة ثنائية المعدن، بدءاً من العملات الأخمينية. فمنذ نحو 515 ق.م. في عهد دريوش الأول، تم استبدال صك الكروسي في ساردس بصك داري Daric وسيگلوي. أول عملة ذهبية من الإمبراطورية الأخمينية، الداري، اتبعت معيار الوزن للكروسي، وبالتالي يعتبر تابعاً ومشتقاً من الكروسي.[12] بعد ذلك تم تعديل وزن الداري من خلال إصلاح مترولوجي، ربما في عهد دريوش الأول.[12]

ظلت ساردس دار سك العملة المركزية لكل من الداري والسيگلوي الفارسيين في العملات الأخمينية، ولا يوجد دليل على وجود أي دور لسك أخرى لسك العملة في عهد الامبراطورية الأخمينية.[13] بالرغم من أن الداري الذهبي أصبح عملة دولية، عـُثِر عليها في أرجاء العالم القديم، إلا أن تداول السيگلوي ظل منحصراً في آسيا الصغرى: وقد عـُثِرَ على كنوز معتبرة من السيگلوي فقط في تلك المناطق، وخارج تلك المناطق لم يُعثر إلى على أعداد قليلية وهامشية بالمقارنة بالعملات اليونانية، حتى في الأقاليم الأخمينية.[13]

الأرجنتين

In 1881, a currency reform in Argentina introduced a bimetallic standard, which went into effect in July 1883.[14] Units of gold and silver pesos would be exchanged with paper peso notes at given par values, and fixed exchange rates against key international currencies would thus be established.[14] Unlike many metallic standards, the system was very decentralized: no national monetary authority existed, and all control over convertibility rested with the five banks of issue.[14] This convertibility lasted only 17 months: from December 1884 the banks of issue refused to exchange gold at par for notes.[14] The suspension of convertibility was soon accommodated[مطلوب توضيح] by the Argentine government, since, having no institutional power over the monetary system, there was little they could do to prevent it.[14]

فرنسا

A French law of 1803 granted anyone who brought gold or silver to its mint the right to have it coined at a nominal charge in addition to the official rates of 200 francs per kilogram of 90% silver, or 3100 francs per kilogram of 90% fine gold.[15] This effectively established a bimetallic standard at the rate which had been used for French coinage since 1785, i.e. a relative valuation of gold to silver of 15.5 to 1. In 1803 this ratio was close to the market rate, but for most of the next half century the market rate was above 15.5 to 1.[15] As a consequence, silver powered the French economy and gold was exported. But when the California Gold Rush increased the supply of gold, its value was reduced relative to silver. The market rate fell below 15.5 to 1, and remained below until 1866. Frenchmen responded by exporting silver to India and importing nearly two-fifths of the world's production of gold in the period from 1848 to 1870.[16] Napoleon III introduced five franc gold coins which provided a substitute for the silver five franc coins which were hoarded,[17] but still maintained the formal bimetallism implicit in the 1803 law.

الاتحاد النقدي اللاتيني

The national coinages introduced in Belgium (1832), Switzerland (1850), and Italy (1861) were based on France's bimetallic currency. These countries joined France in a treaty signed on 23 December 1865 which established the Latin Monetary Union (LMU).[16] Greece joined the LMU in 1868 and about twenty other countries adhered to its standards.[18] The LMU effectively adopted bimetallism by allowing unlimited free coinage of gold and silver at the 15.5 to 1 rate used in France, but also began to back away from bimetallism by allowing limited issues of low denomination silver coins struck to a lower standard for government accounts.[19] A surplus of silver led the LMU to limit free coinage of silver in 1874 and to end it in 1878, effectively abandoning bimetallism for the gold standard.[19]

المملكة المتحدة

Medieval and early modern England used both gold and silver, at fixed rates, to provide the necessary range of coin denominations; but silver coinage began to be restricted in the 18th century, first informally, and then by an Act of Parliament in 1774.[20] After the suspension of metal convertibility from 1797 to 1819, Peel's Bill set the country on the gold standard for the remainder of the century; however advocates of a return to bimetallism did not cease to appear. After the crash of 1825, William Huskisson argued strongly within the Government for bimetallism, as a way to increase credit (as well as to ease trade with South America).[21] Similarly, after the banking crisis of 1847, Alexander Baring headed an external bimetallist movement hoping to prevent the undue restriction of the currency.[22] It was, however, only in the last quarter of the century that the movement for bimetallism gathered real strength, drawing on Manchester cotton merchants and City financiers with Far East interests to offer a serious (if ultimately unsuccessful) challenge to the gold standard.[23]

الولايات المتحدة

في عام 1787 ، أنشأ دستور الولايات المتحدة الذهب والفضة باعتباره العطاء القانوني للولايات المتحدة [24] بسعر صرف عائم . ثم في عام 1792 ، اقترح وزير الخزانة ألكساندر هاملتون تثبيت سعر صرف الفضة إلى الذهب في الساعة 15: 1 ، وكذلك إنشاء دار سك عملة للخدمات العامة للعملات المعدنية المجانية وتنظيم العملة "حتى لا تختزل كمية المتداول المتوسط ". . [25] بموجب المادة 11 من قانون العملات لعام 1792 ، بقبولها : "أن القيمة النسبية للذهب إلى الفضة في جميع العملات المعدنية التي يجب أن تكون حالية كنقود داخل الولايات المتحدة ، يجب أن تكون من خمسة عشر إلى واحد، حسب الكمية في الوزن ، من الذهب الخالص أو الفضة النقية؛ " هبطت النسبة بحلول عام 1834 إلى ستة عشر إلى واحد. حصلت الفضة على نجاح أكبر من خلال قانون العملات لعام 1853 ، عندما تم تقريب جميع فئات العملات الفضية تقريبًا ، مما أدى فعليًا إلى تحويل العملات الفضية إلى عملة ائتمانية استنادًا إلى قيمتها الاسمية بدلاً من قيمتها المرجحة. تم التخلي عن المعادن الثنائية فعليًا بموجب قانون العملة لعام 1873، ولكن لم يتم حظره رسميًا كعملة قانونية حتى أوائل القرن العشرين. كانت مزايا النظام موضوع النقاش في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر. إذا تسببت قوى السوق للعرض والطلب على أي من المعدن في تجاوز قيمة السبائك الخاصة به قيمة العملة الاسمية ، فإنه يميل إلى الاختفاء من التداول عن طريق الكنز أو الذوبان.

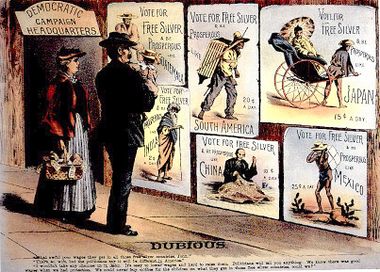

مناقشة سياسية

في الولايات المتحدة ، أصبحت ثنائية المعدن مركزًا للنزاع السياسي قرب نهاية القرن التاسع عشر. خلال الحرب الأهلية ، لتمويل الحرب تحولت الولايات المتحدة من نظام المعدنين إلى النقود الورقية العملات. بعد الحرب ، في عام 1873 ، أقرت الحكومة قانون العملة الرابعة ، وبدأت قريباً استئناف مدفوعات القطع المعدنية (بدون عملات معدنية مجانية وغير محدودة من الفضة ، وبالتالي وضعت الولايات المتحدة على معيار الذهب أحادي المعدنية. ) شكل المزارعون والمدينون والغربيون وغيرهم ممن شعروا أنهم استفادوا من النقود الورقية في زمن الحرب حزب العملة الأمريكية قصير العمر للضغط من أجل النقود الورقية الرخيصة المدعومة بالفضة. [26] ظهر العنصر الأخير - "الفضة الحرة" - على نحو متزايد كإجابة على اهتمامات مجموعات المصالح نفسها ، وتناولته الحركة الشعبوية كنقطة مركزية. [27] أشار مؤيدو الفضة النقدية ، والمعروفة باسم الفضة ، إلى قانون العملة الرابعة باسم "جريمة عام 73" ، حيث تم الحكم على أنها تحول دون التضخم ، وفضلت الدائنين على المدينين. ومع ذلك ، رأى بعض الإصلاحيين ، مثل هنري ديماريست لويد ، ثنائية المعدن بمثابة رنجة حمراء ويخشون أن تكون الفضة المجانية " راعي لحركة الإصلاح ، من المرجح أن تدفع البيض الآخر للخروج من العش. [28] ومع ذلك ، فإن حالة الهلع التي نشبت عام 1893 ، والاكتئاب الشديد في جميع أنحاء البلاد ، جلبت قضية المال بقوة إلى الواجهة مرة أخرى. جادل "الفضيون silverites" أن استخدام الفضة من شأنه أن يؤدي إلى تضخيم عرض النقود ويعني المزيد من النقود للجميع ، والتي يعادلها الازدهار. وقال المدافعون عن الذهب إن الفضة ستؤدي إلى تراجع الاقتصاد بشكل دائم ، لكن الأموال الجيدة التي ينتجها معيار الذهب ستعيد الرخاء.

Bimetallism and "Free Silver" were demanded by William Jennings Bryan who took over leadership of the Democratic Party in 1896, as well as by the Populists, and a faction of Republicans from silver mining regions in the West known as the Silver Republicans who also endorsed Bryan.[29] The Republican Party itself nominated William McKinley on a platform supporting the gold standard which was favored by financial interests on the East Coast.

Bryan, the eloquent champion of the cause, gave the famous "Cross of Gold" speech at the National Democratic Convention on July 9, 1896, asserting that "The gold standard has slain tens of thousands." He referred to "a struggle between 'the idle holders of idle capital' and 'the struggling masses, who produce the wealth and pay the taxes of the country;' and, my friends, the question we are to decide is: Upon which side will the Democratic party fight?" At the peroration, he said: "You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold."[30] However, his presidential campaign was ultimately unsuccessful; this can be partially attributed to the discovery of the cyanide process by which gold could be extracted from low-grade ore. This process and the discoveries of large gold deposits in South Africa (Witwatersrand Gold Rush of 1887 – with large-scale production starting in 1898) and the Klondike Gold Rush (1896) increased the world gold supply and the subsequent increase in money supply that free coinage of silver was supposed to bring. The McKinley campaign was effective at persuading voters in the business East that poor economic progress and unemployment would be exacerbated by the adoption of the Bryan platform.[31] 1896 saw the election of McKinley. The direct link to gold was abandoned in 1934 in Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal program and later the link was broken by Richard Nixon when he closed the gold window.

تحليل إقتصادي

في عام 1992 ، خلص الخبير الاقتصادي ميلتون فريدمان إلى أن التخلي عن المعيار متعلق بنظام المعدنين في عام 1873 أدى إلى عدم استقرار في الأسعار أكبر مما كان يمكن أن يحدث لولا ذلك ، وبالتالي أسفر عن ضرر طويل الأجل للاقتصاد الأمريكي. قاد تحليله بأثر رجعي أن يكتب أن قانون عام 1873 "... كان خطأ كان له عواقب وخيمة للغاية". [32]

انظر أيضا

ملاحظات

المراجع

اقتباسات

- ^ أ ب ت Metcalf, William E. (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage (in الإنجليزية). Oxford University Press. p. 49-50. ISBN 9780199372188.

- ^ Wilson, Alexander Johnstone (1880), Reciprocity, Bi-metallism, and Land-Tenure Reform, London: Macmillan & Co., https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006594733.

- ^ "bimetallism, n.", Oxford English Dictionary, http://oed.com/view/Entry/19090.

- ^ A Model of Bimetallism.

- ^ "Bimetallism", Encyclopædia Britannica.[بحاجة لتوضيح]

- ^ Kindleberger, Charles (1984), A Financial History of Western Europe, London: Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Redish, Angela (1995), "The Persistence of Bimetallism in Nineteenth Century France", Economic History Review.

- ^ Friedman, Milton (1990), "Bimetallism Revisited", Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 4, American Economic Association, pp. 85–104.

- ^ Flandreau, Marc (1996), "The French Crime of 1873: An Essay on the Emergence of the International Gold Standard, 1870–1880", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 56.

- ^ Fisher, William Bayne; Gershevitch, I.; Boyle, John Andrew; Yarshater, Ehsan; Frye, Richard Nelson (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. pp. 616–617. ISBN 9780521200912.

- ^ DARIC – Encyclopaedia Iranica (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ أ ب Fisher, William Bayne; Gershevitch, I.; Boyle, John Andrew; Yarshater, Ehsan; Frye, Richard Nelson (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 617. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ أ ب Fisher, William Bayne; Gershevitch, I.; Boyle, John Andrew; Yarshater, Ehsan; Frye, Richard Nelson (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 619. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج della Paolera, Gerardo; Taylor, Alan M. (2001). "The Argentine Currency Board and the Search for Macroeconomic Stability, 1880–1935" (PDF). University of Chicago Press. pp. 46–48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-16.

- ^ أ ب Dickson Leavens, Silver Money, Chapter IV Bimetallism in France and the Latin Monetary Union, page 25

- ^ أ ب Dickson Leavens, op. cit. page 26

- ^ John Porteous, Coins in History, page 238

- ^ Robert Friedberg, Gold Coins of the World, fourth edition, page 11

- ^ أ ب John Porteous, op. cit. page 241

- ^ A. Redish, Bimetallism (2006) p. 67 and p. 205

- ^ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad & Dangerous People? (Oxford, 2008) p. 303

- ^ É. Halévy, Victorian Years (London: Ernest Benn, 1961) p. 201

- ^ P. J. Cain, British Imperialism (2016) pp. 155–6 and p. 695

- ^ U.S. Constitution

- ^ 2 Annals of Cong. 2115 (1789–1791), cited in آرثر نوسباوم، The Law of the Dollar, Columbia Law Review, Vol. 37, No. 7 (Nov., 1937), pp. 1057–1091

- ^ R. B. Nye, the Growth of the United States (Penguin 1955) p. 599-603

- ^ H. G, Nicholas, The American Union (Penguin 1950) p. 220

- ^ Quoted in R. B. Nye, the Growth of the United States (Penguin 1955) p. 603

- ^ R. B. Nye, the Growth of the United States (Penguin 1955) p. 603

- ^ R. B. Nye, the Growth of the United States (Penguin 1955) p. 604

- ^ H. G, Nicholas, The American Union (Penguin 1950) p. 222

- ^ Milton Friedman, Money Mischief (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992) 78.

قائمة المراجع

المصادر الأولية

- Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party (1896) by Democratic Party (U.S.) National Committee: this is the Gold Democrats handbook; it strongly opposed Bryan.

- Walker, International Bimetallism (New York, 1896)

- Robert Giffen, Case against Bimetallism (London, 1896)

- Joseph Shield Nicholson, Money and Monetary Problems (London, 1897)

- Samuel Dana Horton, The Silver Pound (London, 1887)

- Walker, Money (New York, 1878)

- Francis Amasa Walker, Money, Trade and Industry (New York, 1879)

- Elisha Benjamin Andrews, An honest Dollar (Hartford, 1894)

- Helm, The Joint Standard (London, 1894)

- Frank William Taussig, The Silver Situation in the United States (New York, 1893)

- Horace White (writer), Money and Banking (Boston, 1896)

- James Laurence Laughlin, History of Bimetallism in the United States (New York, 1897)

- Langford Lovell Price, Money and its Relations to Prices (London and New York, 1896)

- Utley, Bimetallism (Los Angeles, 1899)

- Roger Q. Mills, What shall we do with silver? (The North American Review, Volume 150, Issue 402, May 1890.)

مصادر ثانوية

- Epstein, David A. (2012). Left, Right, Out: The History of Third Parties in America. Arts and Letters Imperium Publications. ISBN 978-0-578-10654-0.

- James A. Barnes, "Myths of the Bryan Campaign," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 34 (December 1947) online in JSTOR

- David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, "Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900," Independent Review 4 (Spring 2000), 555-75.

- Bordo, Michael D. "Bimetallism." in The New Palgrave Encyclopedia of Money and Finance edited by Peter K. Newman, Murray Milgate and John Eatwell. 1992.

- Dighe, Ranjit S. ed. The Historian's Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum's Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory (2002)

- Flandreau, Marc, 2004, The Glitter of Gold. France, Bimetallism and the Emergence of the International Gold Standard, 1848–1873, Oxford, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 343 p.

- Friedman, Milton, 1990a, "The crime of 1873," Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, No. 6, December, pp. 1159–1194 in JSTOR

- Friedman, Milton, 1990b, "Bimetallism revisited," Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 4, No. 4, Fall, pp. 85–104. in JSTOR

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz, 1963, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00354-8.

- Jeansonne, Glen. "Goldbugs, Silverites, and Satirists: Caricature and Humor in the Presidential Election of 1896." Journal of American Culture 1988 11(2): 1–8. ISSN 0191-1813

- Jensen, Richard J. (1971). The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict 1888–1896.

- Jones, Stanley L. (1964). The Presidential Election of 1896.

- Littlefield, Henry M., 1964, "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism," American quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 1, Spring, pp. 47–58.

- Angela Redish, "Bimetallism"

- Rockoff, Hugh, 1990, "The Wizard of Oz as a monetary allegory," Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, No. 4, August, pp. 739–760. in JSTOR

- Velde, Francois R. "Following the Yellow Brick Road: How the United States Adopted the Gold Standard" Economic Perspectives. Volume: 26. Issue: 2. 2002.

- Richard Hofstadter (1996). "Free Silver and the Mind of "Coin" Harvey". The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays. Harvard University Press. Harvard. ISBN 0-674-65461-7.

روابط خارجية

- The Bimetallic Standard, a series of pages on bimetalism from Micheloud & cie.

- Speeches before the 51st Congress (1889-1891) regarding "free silver," digitized and available on FRASER (Federal Reserve Archival System for Economic Research).

- Speeches before the 52nd Congress (1891-1893) regarding "free silver," digitized and available on FRASER (Federal Reserve Archival System for Economic Research).

- Speeches before the 53rd Congress (1893-1895) regarding "free silver," digitized and available on FRASER (Federal Reserve Archival System for Economic Research).

- The French Crime of 1873: An Essay on the Emergence of the International Gold Standard, 1870–1880 (PDF)

- Articles with links needing disambiguation

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from June 2017

- ربط العملة بمعدن

- التاريخ الاقتصادي للولايات المتحدة

- مصطلحات المسكوكات

- حزب الشعب (الولايات المتحدة)

- فضة

- ذهب

- علم الاقتصاد النقدي

- عملة