تاريخ الهندوسية

| مقالات عن |

| الهندوسية |

|---|

|

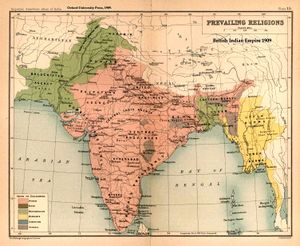

تاريخ الهندوسية يشير إلى تشكيلة واسعة من الطوائف الهندوسية المترابطة التي نشأت في شبه القارة الهندية، ومعظمهم يتواجد في ما هو اليوم الهند ونـِپال وپاكستان وبنگلادش وأفغانستان.[1] ويوجد أتباع أيضاً في جزيرة بالي الإندونيسية. ويتراكب تاريخها أو يتزامن مع تطور الديانات الهندية منذ الهند في العصر الحديدي. ولذلك فيقال عنها أنه "أقدم ديانة حية" في العالم.[note 1] ويعتبر الدارسون الهندوسية كتخليق[2][3][4] من ثقافات وتقاليد هندية مختلفة،[3][5][2] بجذور متباينة[6] بدون مؤسس واحد أو مصدر واحد.[7][note 2]

تاريخ الهندوسية is often divided into periods of development, with the first period being that of the الديانة الڤيدية التاريخية التي تعود إلى ما بين 1900 ق.م. و 1400 ق.م..[8][note 3] The subsequent period, between 800 BCE and 200 BCE, is "a turning point between the Vedic religion and Hindu religions",[11] and a formative period for Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. The Epic and Early Puranic period, from c. 200 BCE to 500 CE, saw the classical "Golden Age" of Hinduism (c. 320-650 CE), which coincides with the Gupta Empire. In this period the six branches of Hindu philosophy evolved, namely Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedanta. Monotheistic sects like Shaivism and Vaishnavism developed during this same period through the Bhakti movement. The period from roughly 650 to 1100 CE forms the late Classical period[12] or early Middle Ages, in which classical Puranic Hinduism is established, and Adi Shankara's Advaita Vedanta, which incorporated Buddhist thought into Vedanta, marking a shift from realistic to idealistic thought.

شهدت الهندوسية تحت حكم كلٍ من الحكام الهندوس والمسلمين منذ ح. 1200 إلى 1750م،[13][14] أهمية متزايدة لحركة باكتي، التي مازالت مؤثرة حتى اليوم. The colonial period saw the emergence of various حركات الإصلاح الهندوسية partly inspired by western movements, such as Unitarianism and Theosophy. The Partition of India in 1947 was along religious lines, with the Republic of India emerging with a Hindu majority. During the 20th century, due to the Indian diaspora, Hindu minorities have formed in all continents, with the largest communities in absolute numbers in the United States and the United Kingdom. In the Republic of India, Hindu nationalism has emerged as a strong political force since the 1980s, the Hindutva Bharatiya Janata Party forming the Government of India from 1999 to 2004, and its first state government in South India in 2006, and also the Narendra Modi led Government from 2014.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التقسيم إلى فترات

جيمس ميل (1773–1836)، في كتابه The History of British India (1817), distinguished three phases in the history of India, namely Hindu, Muslim and British civilisations. This periodisation has been criticised, for the misconceptions it has given rise to. Another periodisation is the division into "ancient, classical, medieval and modern periods", although this periodization has also received criticism.[15]

Romila Thapar notes that the division of Hindu-Muslim-British periods of Indian history gives too much weight to "ruling dynasties and foreign invasions,"[16] neglecting the social-economic history which often showed a strong continuity.[16] The division in Ancient-Medieval-Modern overlooks the fact that the Muslim-conquests took place between the eighth and the fourteenth century, while the south was never completely conquered.[16] According to Thapar, a periodisation could also be based on "significant social and economic changes," which are not strictly related to a change of ruling powers.[17][note 4]

Smart and Michaels seem to follow Mill's periodisation, while Flood and Muesse follow the "ancient, classical, medieval and modern periods" periodisation. An elaborate periodisation may be as follows:[12]

- Pre-history and Indus Valley Civilisation (until c. 1750 BCE);

- Vedic period (c. 1750-500 BCE);

- "Second Urbanisation" (c. 600-200 BCE);

- Classical Period (c. 200 BCE-1200 CE);[note 5]

- Pre-classical period (c. 200 BCE – 300 CE);

- "Golden Age" of India (Gupta Empire) (ح. 320–650 CE);

- Late-Classical period (c. 650–1200 CE);

- Medieval Period (ح. 1200–1500 CE);

- Early Modern Period (c. 1500–1850);

- Modern period (British Raj and independence) (from c. 1850).

| تاريخ الهندوسية | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Mill (1773–1836), in his The History of British India (1817),[A] distinguished three phases in the history of India, namely Hindu, Muslim and British civilisations.[A][B] This periodisation has been influential, but has also been criticised, for the misconceptions it has given rise to.[C] Another influential periodisation is the division into "ancient, classical, mediaeval and modern periods".[D] | |||||||||||||

| Smart[E] | Michaels (overall)[F] |

Michaels (detailed)[F] |

Muesse[G] | Flood[H] | |||||||||

| Indus Valley civilisation and Vedic period (c. 3000–1000 BCE) |

Prevedic religions (until c. 1750 BCE)[I] |

Prevedic religions (until c. 1750 BCE)[I] |

Indus Valley civilisation (3300–1400 BCE) |

Indus Valley civilisation (c. 2500 to 1500 BCE) | |||||||||

| Vedic religion (c. 1750–500 BCE) |

Early Vedic Period (c. 1750–1200 BCE) |

Vedic period (1600–800 BCE) |

Vedic period (c. 1500–500 BCE) | ||||||||||

| Middle Vedic Period (from 1200 BCE) | |||||||||||||

| Pre-classical period (c. 1000 BCE – 100 CE) |

Late Vedic period (from 850 BCE) |

Classical Period (800–200 BCE) | |||||||||||

| Ascetic reformism (c. 500–200 BCE) |

Ascetic reformism (c. 500–200 BCE) |

Epic and Puranic period (c. 500 BCE to 500 CE) | |||||||||||

| Classical Hinduism (c. 200 BCE – 1100 CE)[J] |

Preclassical Hinduism (c. 200 BCE – 300 CE)[K] |

Epic and Puranic period (200 BCE – 500 CE) | |||||||||||

| Classical period (c. 100 – 1000 CE) |

"Golden Age" (Gupta Empire) (c. 320–650 CE)[L] | ||||||||||||

| Late-Classical Hinduism (c. 650–1100 CE)[M] |

Medieval and Late Puranic Period (500–1500 CE) |

Medieval and Late Puranic Period (500–1500 CE) | |||||||||||

| Hindu-Islamic civilisation (c. 1000–1750 CE) |

Islamic rule and "Sects of Hinduism" (c. 1100–1850 CE)[N] |

Islamic rule and "Sects of Hinduism" (c. 1100–1850 CE)[N] | |||||||||||

| Modern Age (1500–present) |

Modern period (c. 1500 CE to present) | ||||||||||||

| Modern period (ح. 1750 CE – الحاضر) |

Modern Hinduism (from c. 1850)[O] |

Modern Hinduism (from c. 1850)[O] | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

الديانات قبل الڤيدية (حتى ح. 1750 ق.م.)

قبل التاريخ

Hinduism may have roots in Mesolithic prehistoric religion, such as evidenced in the rock paintings of Bhimbetka rock shelters,[note 6] which are about 10,000 years old (c. 8,000 BCE),[18][19][20][21][22] as well as neolithic times. At least some of these shelters were occupied over 100,000 years ago.[23][note 7] Several tribal religions still exist, though their practices may not resemble those of prehistoric religions.[web 1]

حضارة وادي السند (c. 3300–1700 BCE)

Some Indus valley seals show swastikas, which are found in other religions worldwide. Phallic symbols interpreted as the much later Hindu linga have been found in the Harappan remains.[24][25] Many Indus valley seals show animals. One seal shows a horned figure seated in a posture reminiscent of the Lotus position and surrounded by animals was named by early excavators "Pashupati", an epithet of the later Hindu gods Shiva and Rudra.[26][27][28] Writing in 1997, Doris Meth Srinivasan said, "Not too many recent studies continue to call the seal's figure a "Proto-Siva," rejecting thereby Marshall's package of proto-Shiva features, including that of three heads. She interprets what John Marshall interpreted as facial as not human but more bovine, possibly a divine buffalo-man.[[#cite_note-FOOTNOTESrinivasan1997[[تصنيف:مقالات_بالمعرفة_بحاجة_لذكر_رقم_الصفحة_بالمصدر_from_March_2021]][[Category:Articles_with_invalid_date_parameter_in_template]]<sup_class="noprint_Inline-Template_"_style="white-space:nowrap;">[<i>[[المعرفة:Citing_sources|<span_title="هذه_المقولة_تحتاج_مرجع_إلى_صفحة_محددة_أو_نطاق_من_الصفحات_تظهر_فيه_المقولة'"`UNIQ--nowiki-00000068-QINU`"'_(March_2021)">صفحة مطلوبة</span>]]</i>]</sup>-62|[29]]] According to Iravatham Mahadevan, symbols 47 and 48 of his Indus script glossary The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables (1977), representing seated human-like figures, could describe the South Indian deity Murugan.[30]

In view of the large number of figurines found in the Indus valley, some scholars believe that the Harappan people worshipped a mother goddess symbolizing fertility, a common practice among rural Hindus even today.[31] However, this view has been disputed by S. Clark who sees it as an inadequate explanation of the function and construction of many of the figurines.[32]

There are no religious buildings or evidence of elaborate burials... If there were temples, they have not been identified.[33] However, House – 1 in HR-A area in Mohenjadaro's Lower Town has been identified as a possible temple.[34]

شعار ما يسمى شيڤا پاشوپاتي ("شيڤا، رب الحيوانات") من حضارة وادي السند.

Fighting scene between a beast and a man with horns, hooves and a tail, who has been compared to the Mesopotamian bull-man Enkidu.[38][39][40] Indus Valley Civilisation seal.

شعارات سواستيكا (صليب معقوف) من حضارة وادي السند محفوظة في المتحف البريطاني

الفترة الڤيدية (ح. 1750–500 ق.م.)

| ||

|

The commonly proposed period of earlier Vedic age is dated back to 2nd millennium BCE.[41] Vedism was the sacrificial religion of the early Indo-Aryans, speakers of early Old Indic dialects, ultimately deriving from the Proto-Indo-Iranian peoples of the Bronze Age who lived on the Central Asian steppes.[note 8]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

جذور الهندوسية

الديانة الهندية - براهما، فشنو، شيفا - كرشنا - كالي الآلهة الحيوانية - البقرة المقدسة - تعدد الآلهة والوحدانية

لم تكن الديانة الهندية التي حلت محل البوذية ديانة واحدة، كلا ولا كانت مقتصرة على كونها عقيدة دينية؛ بل كانت خليطاً من عقائد وطقوس لا يشترك القائمون بها في أكثر من أربع صفات؛ فهم يعترفون بنظام الطبقات وبزعامة البراهمة، وهم يقدسون البقرة باعتبارها تمثل الألوهية على نحو تمتاز به من سواها، وهم يقبلون قانون "كارما" وتناسخ الأرواح، وهم يضيفون إلى آلهتهم الجديدة آلهة الفيدات؛ ولقد كان بعض هذه العقائد أسبق من عبادة الطبيعة التي جاءت بها الفيدا، كما ظلت قائمة بعد زوال تلك العبادة، وأما بعضها الآخر فقد نشأ من أن البراهمة كانوا يغضون أبصارهم عن ضروب من الطقوس والآلهة والعقائد لم ينص عليها كتابهم المقدس، بل تناقضه روح الفيدا مناقضة ليست باليسيرة؛ فأتيحت الفرصة لتلك العقائد أن تنضج في وعاء الفكر الديني عند الهنود، ومضت في نضجها ذاك حتى في الفترة العابرة التي ارتفعت فيها البوذية إلى مكان السيادة العقلية في البلاد.

كان آلهة العقيدة الهندية يتميزون بكثرة أعضائهم الجسدية التي يمثلون بها على نحو غامض قدرتهم الخارقة في العلم والنشاط والقوة؛ "فبراهما" الجديد كان له أربعة وجوه، وكان لـ "كارتكيا" ستة وجوه، ولـ "شيفا" ثلاثة أعين، ولـ "هندرا" ألف عين؛ وكل إله عندهم تقريباً كان له أربع أذرعة(10) وعلى رأس هذه المجموعة الجديدة من الآلهة "براهما" الذي كان له من الشهامة ما أبعده عن الميل مع الهوى، وهو سيد الآلهة المعترف له بتلك السيادة، على الرغم من أنه مهمل في شعائر العبادة الفعلية إهمال الملك الدستوري في أوربا الحديثة؛ و"براهما" و"شيفا" و"فشنو" هم الثلاثة الآلهة (لا الثالوث) الذي يسيطرون على الكون، وأما "فشنو" فهو إله الحب الذي كثيراً ما انقلب إنسانا ليتقدم بالعون إلى بني الإنسان؛ وأعظم من يتجسد فيه "فشنو" هو "كرشنا" ، وهو في صورته "الكرشنية" هذه، قد ولد في سجن وأتى بكثير من أعاجيب البطولة والغرام، وشفى الصم والعمي، وعاون المصابين بداء البرص، وذاد عن الفقراء، وبعث الموتى من قبورهم؛ وكان له تلميذ محبب إلى نفسه، وهو "أرجونا" ، وأمام "أرجونا" تبدلت خلقة "فشنو" حالاً بعد حال؛ ويزعم بعض الرواة أنه مات مطعوناً بسهم، ويزعم آخرون أنه قتل مصلوباً على شجرة؛ وهبط إلى جهنم ثم صعد إلى السماء، على أن يعود في اليوم الآخر ليحاسب الناس أحياءهم وأمواتهم(11).

الحياة، بل الكون كله، لها في رأي الهندي ثلاثة وجوه رئيسية: الخلق، والاحتفاظ بالمخلوق، ثم الفناء؛ ومن ثم كان للألوهية عنده ثلاث صور: براهما الخالق، وفشنو الحافظ، وشيفا المدمر؛ تلك هي "الأشكال الثلاثة" التي يقدسها الهنود أجمعين ماعدا الجانتيين منهم ؛ والناس منقسمون بحبهم طائفتين: إحداهما تميل إلى ديانة فشنو، والأخرى إلى ديانة شيفا؛ وكلتا العقيدتين بمثابة الجارتين المسالمتين، بل قد تتقدم كلتاهما بالقرابين في معبد واحد(13)، والحكماء من البراهمة- تتبعهم الأكثرية العظمى من سواد الناس- تكرم الإلهين معاً بغير تمييز لأحدهما؛ أما الفشنيون الأتقياء فيرسمون على جباههم كل صباح بالطين الأحمر علامة فشنو، وهي شوكة ذات أسنان ثلاث؛ وأما الشيفيون المخلصون لعقيدتهم فيرسمون ثلاثة خطوط أفقية على جباههم برماد من روث البقر، أو يلبسون "اللنجا"- رمز عضو الذكورة- ويربطونه على أذرعتهم أو يعلقونه حول أعناقهم(14).

وعبادة "شيفا" هي من أقدم وأعمق وأبشع العناصر التي منها تتألف الديانة الهندية؛ فيقدم لنا "سير جون مارشل" "دليلاً لا يأتيه الباطل" على أن عقيدة "شيفا" كانت موجودة في "موهنجو- دارو"، متخذة أحياناً صورة شيفا ذي الرءوس الثلاثة، وأحياناً أخرى صورة أعمدة حجرية صغيرة، يزعم لنا أنها ترمز لعضو الذكورة على نحو ما ترمز له عندهم بدائلها في العصر الحديث؛ وهو يخلص من ذلك إلى نتيجة هي أن "العقيدة الشيفية أقدم عقيدة حية في العالم كله" . واسم الإله- أعني كلمة شيفا- لفظة أريد بها التخفيف من بشاعة هذا الإله، فالكلمة شيفا معناها الحرفي "العطوف" مع أن شيفا في حقيقة الأمر إله القسوة والتدمير قبل كل شئ آخر؛ هو تجسيد لتلك القوة الكونية التي تعمل واحدة بعد أخرى، على تخريب جميع الصور التي تتبدى فيها حقيقة الكون- جميع الخلايا الحية وجميع الكائنات العضوية، وكل الأنواع، وكل الأفكار وكل ما أبدعته يد الإنسان، وكل الكواكب، وكل شيء؛ ولم يسبق الهنود شعب قط في شجاعتهم في مواجهة الحقيقة التي هي عدم ثبات الأشياء على صورها ووقوف الطبيعة من كل شئ موقف الحياد، مواجهة صريحة ؛ولم يسبقهم شعب قط في اعترافهم اعترافاً واضحاً بأن الشر يتوازن مع الخير، والهدم يساير الخلق خطوة خطوة، وأن ولادة الأحياء بأسرها جريمة كبرى عقابها الموت؛ فالهندي الذي تعذبه آلاف العوامل من عثرة الحظ والآلام، يرى في تلك الألوان من التعذيب أثراً ينم عن قوة نشيطة يمتعها- فيما يظهر- أن تحطم كل ما أنتجه براهما، وهو القوة الخالقة في الطبيعة؛ إن "شيفا" ليطرب راقصاً إذا ما سمع نغمة العالم فأدرك منها عالماً لا يني يتكون وينحل ويعود إلى التكون من جديد.

ولكن كما أن الموت عقوبة الولادة، فكذلك الولادة تخييب لرجاء الموت؛ فالإله نفسه الذي يرمز للتدمير، يمثل كذلك للعقل الهندي تلك الدفعة الجارفة نحو التناسل الذي يتغلب على موت الفرد باستمرار الجنس؛ وهذه الحيوية الخلاقة الناسلة (شاكتي) التي يبديها شيفا- أو الطبيعة- تتمثل في بعض جهات الهند، وخصوصاً في البنغال، في صورة زوجة شيفا، واسمها "كالي" (بارفاتي، أو أوما أو درجا) وهي موضع عبادة في عقيدة من العقائد الكثيرة التي تأخذ بمذهب "الشاكتي" هذا؛ ولقد كانت هذه العبادة- حتى القرن الماضي- وحشية الطقوس كثيراً ما تتضمن في شعائرها تضحية بشرية، لكن الآلهة اكتفت بعدئذ بضحايا الماعز(17)؛ وهذه الآلهة صورتها عند عامة الناس شبح أسود بفم مفغور ولسان متدل، تزدان بالأفاعي وترقص على جثة ميتة؛ وأقراطها رجال موتى، وعقدها سلسلة من جماجم، ووجهها وثدياها تلطخها الدماء(18) ومن أيديها الأربعة يدان تحملان سيفاً ورأساً مبتوراً، وأما اليدان الأخريان فممدودتان رحمة وحماية؛ لأن "كالي- بارفالي" هي كذلك الإله الأمومة كما أنها عروس الدمار والموت؛ وفي وسعها أن تكون رقيقة الحاشية كما في وسعها أن تكون قاسية، وفي مقدورها أن تبتسم كما في مقدورها أن تقتل؛ ولعلها كانت ذات يوم إلهة أماً في سومر، ومن ثم جاءت إلى الهند قبل أن تتخذ هذا الجانب البشع من جانبيها(19) ولاشك أنها هي وزوجها قد اتخذا أبشع صورة ممكنة لكي يلقيا الرعب في نفوس الرعاديد من عبادها فيحتشموا، أو قد تكون هذه البشاعة كلها قد أريد بها أن يلقي الرعب في نفوس العباد فيجودوا بالعطاء للكهنة .

تلك هي أعظم آلهة الهندوسيين، لكنا لم نذكر إلا خمسة من ثلاثين مليوناً من الآلهة تزدحم بها مقبرة العظماء في الهند؛ ولو أحصينا أسماء هاتيك الآلهة لاقتضى ذلك مائة مجلد؛ وبعضها أقرب في طبيعته إلى الملائكة، وبعضها هو ما قد نسميه نحن بالشياطين، وطائفة منها أجرام سماوية مثل الشمس، وطائفة منها تمائم مثل "لاكشمي" (إلهة الحظ الحسن)، وكثير منها هي حيوانات الحقل أو طيور السماء؛ فالهندي لا يرى فارقاً بعيداً بين الحيوان والإنسان، فالحيوان روح كما للإنسان، والأرواح تمضي دواماً متنقلة من بني الإنسان إلى بني الحيوان، ثم تعود إلى بني الإنسان مرة أخرى؛ وكل هذه الصنوف الإلهية قد نسجت خيوطها في شبكة واحدة لا نهاية لحدودها، هي "كارما" وتناسخ الأرواح؛ فالفيل مثلاً قد أصبح الإله "جانيشا" واعتبروه ابن شيفا(21)، وفيه تتجسد طبيعة الإنسان الحيوانية، وكانت صورته في الوقت نفسه تتخذ طلسماً يقي حامله من الحظ السيئ؛ كذلك كانت القردة والأفاعي مصدر رعب، فكانت لذلك من طبيعة الآلهة؛ فالأفعى التي تؤدي عضة واحدة منها إلى موت سريع، واسمها "ناجا" كان لها عندهم قدسية خاصة؛ وترى الناس في كثير من أجزاء الهند يقيمون كل عام حفلاً دينياً تكريماً للأفاعي، ويقدمون العطايا من اللبن والموز لأفاعي "الناجا" عند مداخل جحورها(22)؛ كذلك أقيمت المعابد تمجيداً للأفاعي كما هي الحال في شرقي ميسور، وهناك في هذه المعابد تسكن جموع زاخرة من الزواحف، ويقوم الكهنة على إطعامها والعناية بها(23)؛ وللتماسيح والنمور والطواويس والببغاوات، بل والفئران حقها من العبادة(24).

وأكثر الحيوان قدسية عند الهندي هي البقرة، فنرى تماثيل الثيرة مصنوعة من كل مادة وفي شتى الأحجام تراها في المعابد والمنازل وميادين المدن؛ وأما البقرة نفسها فأحب الكائنات الحية جميعاً إلى الهنود، ولها مطلق الحرية في ارتياد الطرقات كيف شاءت، وروثها يستخدم وقوداً أو مادة مقدسة يتبركون بها، وبولها خمر مقدس يطهر كل ما في الجسم من نجاسة في الظاهر والباطن؛ ولا يجوز للهندي تحت أي ظرف أن يأكل لحمها أو أن يصطنع من جلدها لباساً يرتديه- فلا يصنع منه غطاء للرأس ولا قفازاً ولا حذاء؛ وإذا ماتت البقرة وجب دفنها بجلال الطقوس الدينية(25)، ولعل السياسة الحكيمة هي التي رسمت فيما مضى هذا التحريم احتفاظاً للزراعة بحيوان الجر حتى يسد حاجة السكان الذين يتكاثرون(26)، وقد بلغ عدد البقر اليوم ربع عدد السكان(27) ووجهة نظر الهندي في ذلك هي أنه ليس أبعد عن المعقول أن تشعر بالحب العميق للبقرة والمقت الشديد لفكرة أكلها، من أن تكن أمثال هذه المشاعر للحيوانات المستأنسة من قطط وكلاب، لكن الذي يبعث على السخرية المرة في الأمر هو عقيدة البراهمة بأن الأبقار لا يجوز ذبحها قط، وأن الحشرات لا يحل إيذاؤها قط، وأن الأرامل من النساء ينبغي أن يحرقن أحياء؛ فحقيقة الأمر هي أن عبادة الحيوان قد ظهرت في تاريخ الشعوب كلها، فإن جاز للإنسان أن يؤلمه الحيوان اطلاقاً، فالبقرة الرحيمة الهادئة حقها في هذا التقديس؛ ولا يجوز لنا أن نغلو في كبريائنا حين تأخذنا الدهشة لهذه المعارض الحيوانية من آلهة الهنود، فلنا كذلك إبليس عدن في صورة حية، والثور الذهبي في العهد القديم من الإنجيل، والسمك المقدس في سراديب الموتى، وحمل الله الوديع.

إن سر تعدد الآلهة هو عجز العقل الساذج عن التفكير فيما ليس مشخصاً؛ فأيسر عليه أن يفهم الأشخاص من أن يعقل القوى، وأن يفهم الإرادات من أن يتصور القوانين(28)، والظن عند الهندي هو أن حواسنا البشرية لا ترى من الحوادث التي تدركها سوى ظاهرها، ويعتقد أن وراء هذه الظواهر كائنات روحية لا حصر لعددها، يمكن إدراكها بالعقل لا بالحواس- على حد تعبير "كانت"؛ ولقد أدى تسامح البراهمة ذو المسحة الفلسفية، إلى الزيادة من ذخيرة آلهتهم حتى ازدادت كثرة على كثرة، وذلك أن الآلهة المحليين وآلهة القبائل المختلفة قد صادفت عند الهندي سهلاً ومرحباً، فقبلها وفسرها بأنها جميعاً تصور جوانب من آلهته الأصلية؛ فكل عقيدة يسمح لها بالدخول عندهم إن كان في مستطاعها أن تدفع الضريبة على ذلك؛ حتى كاد كل إله آخر الأمر أن يكون صورة أو صفة أو تجسيداً لإله آخر، ثم تناول العقل الهندي الرشيد كل هذه الآلهة فدمجها في إله واحد؛ هكذا تحول تعدد الآلهة إلى عقيدة بوحدة الوجود، أوشكت عندهم أن تكون توحيداً، والتوحيد بدوره أوشك أن يكون عندهم واحدية فلسفية؛ فكما يتوجه المسيحي الورع بالدعاء إلى العذراء، أو إلى قديس من آلاف القديسين ومع ذلك لا يتحول عن توحيده لله، بمعنى أنه لا يعترف إلا بإله واحد على أنه ذو الجلال الأسمى، فكذلك الهندي يتوجه بالدعاء إلى "كالي" أو "راما" أو "كرشنا" أو "جانيشا" دون أن يتطرق إلى ذهنه لحظة واحدة أن هذه آلهة لها السيادة العليا فترى بعض الهنود يتخذ من "فشنو" إلهاً أعلى، وبعضهم يتخذ من "شيفا" إلهاً أعلى، ويجعل فشنو أحد ملائكته؛ وإذا وجدت بين الهنود أقلية تعبد "براهما" فما ذلك إلا لأنه مجرد عن التشخص، ممتنع على الحواس، بعيد عن البشر، ولهذا السبب عينه ترى معظم الكنائس في البلاد المسيحية قد أقيمت تكريماً لمارية أو لأحد القديسين، وكان على المسيحية أن تنتظر حتى يجيئها فولتير فيقيم معبداً لله.

الديانة الريگڤيدية

| “ | "Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it? Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation? The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe. Who then knows whence it has arisen?" |

” |

—Nasadiya Sukta, concerns the origin of the universe, Rigveda, 10:129-6[42][43][44] | ||

الڤيدات

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الترتيب الكوني

Ethics in the Vedas are based on the concepts of Satya and Ṛta. Satya is the principle of integration rooted in the Absolute.[47] Ṛta is the expression of Satya, which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it.[48] Conformity with Ṛta would enable progress whereas its violation would lead to punishment. Panikkar remarks:

Ṛta is the ultimate foundation of everything; it is "the supreme", although this is not to be understood in a static sense. [...] It is the expression of the primordial dynamism that is inherent in everything...."[49]

The term "dharma" was already used in Brahmanical thought, where it was conceived as an aspect of Rta.[50] The term rta is also known from the Proto-Indo-Iranian religion, the religion of the Indo-Iranian peoples prior to the earliest Vedic (Indo-Aryan) and Zoroastrian (Iranian) scriptures. Asha[pronunciation?] (aša) is the Avestan language term corresponding to Vedic language ṛta.[51]

الأوپانيشاد

The 9th and 8th centuries BCE witnessed the composition of the earliest Upanishads.[52] Upanishads form the theoretical basis of classical Hinduism and are known as Vedanta (conclusion of the Veda).[53] The older Upanishads launched attacks of increasing intensity on the rituals, however, a philosophical and allegorical meaning is also given to these rituals. In some later Upanishads there is a spirit of accommodation towards rituals. The tendency which appears in the philosophical hymns of the Vedas to reduce the number of gods to one principle becomes prominent in the Upanishads.[54] The diverse monistic speculations of the Upanishads were synthesised into a theistic framework by the sacred Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita.[55]

البراهمانية

Brahmanism, also called Brahminism, developed out of the Vedic religion, incorporating non-Vedic religious ideas, and expanding to a region stretching from the northwest Indian subcontinent to the Ganges valley.[56] Brahmanism included the Vedic corpus, but also post-Vedic texts such as the Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras, which gave prominence to the priestly (Brahmin) class of the society.[56] The emphasis on ritual and the dominant position of Brahmans developed as an ideology developed in the Kuru-Pancala realm, and expanded into a wider realm after the demise of the Kuru-Pancala realm.[57] It co-existed with local religions, such as the Yaksha cults.[58][59][web 3]

في هند العصر الحديدي, during a period roughly spanning the 10th to 6th centuries BCE, the Mahajanapadas arise from the earlier kingdoms of the various Indo-Aryan tribes, and the remnants of the Late Harappan culture. In this period the mantra portions of the Vedas are largely completed, and a flowering industry of Vedic priesthood organised in numerous schools (shakha) develops exegetical literature, viz. the Brahmanas. These schools also edited the Vedic mantra portions into fixed recensions, that were to be preserved purely by oral tradition over the following two millennia.

التمدن الثاني وانحدار البراهمانية (ح. 600–200 ق.م.)

الأوپانيشاد وحركات الشرامانيا

Vedism, with its orthodox rituals, may have been challenged as a consequence of the increasing urbanisation of India in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, and the influx of foreign stimuli initiated with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley (circa 535 BCE).[60][61] New ascetic or sramana movements arose, which challenged established religious orthodoxy, such as Buddhism, Jainism and local popular cults.[60][61] The anthropomorphic depiction of various deities apparently resumed in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, also as the consequence of the reduced authority of Vedism.[60]

امبراطورية موريا

شهدت الفترة المورية ازدهاراً مبكراً لأدب سوترا وشاسترا بالسنسكريتية الكلاسيكية والعرض العلمي لمجالات "محيط الڤيدية" في ڤيدانگا. ومع ذلك ، خلال هذا الوقت كانت البوذية تحت رعاية أشوكا، الذي حكم أجزاء كبيرة من الهند ، وكانت البوذية أيضًا الديانة السائدة حتى عصر گوپتا.

انحدار البراهمانية

الانحدار

The post-Vedic period of the Second Urbanisation saw a decline of Brahmanism.[62][63][note 9] At the end of the Vedic period, the meaning of the words of the Vedas had become obscure, and was perceived as "a fixed sequence of sounds"[64][note 10] with a magical power, "means to an end."[note 11] With the growth of cities, which threatened the income and patronage of the rural Brahmins; the rise of Buddhism; and the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great (327-325 BCE), the expansion of the Maurya Empire (322-185 BCE) with its embrace of Buddhism, and the Saka invasions and rule of northwestern India (2nd c. BC – 4th c. CE), Brahmanism faced a grave threat to its existence.[65][66] In some later texts, Northwest-India (which earlier texts consider as part of "Aryavarta") is even seen as "impure", probably due to invasions.

نجاة الطقوس الڤيدية

Vedism as the religious tradition of a priestly elite was marginalised by other traditions such as Jainism and Buddhism in the later Iron Age, but in the Middle Ages would rise to renewed prestige with the Mimamsa school, which as well as all other astika traditions of Hinduism, considered them authorless (apaurusheyatva) and eternal. A last surviving elements of the Historical Vedic religion or Vedism is Śrauta tradition, following many major elements of Vedic religion and is prominent in South India, with communities in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, but also in some pockets of Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and other states; the best known of these groups are the Nambudiri of Kerala, whose traditions were notably documented by Frits Staal.[67][68][69]

التخليق الهندوسي والهندوسية الكلاسيكية (ح. 200 ق.م. – 1200 م)

الهندوسية المبكرة (ح. 200 ق.م. – 320 م)

التخليق الهندوسي

مدارس الفلسفة الهندوسية

In early centuries CE several schools of Hindu philosophy were formally codified, including Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Purva-Mimamsa and Vedanta.[75]

أدب سانگام

The Sangam literature (300 BCE – 400 CE), written in the Sangam period, is a mostly secular body of classical literature in the Tamil language. Nonetheless, there are some works, significantly Pattupathu and Paripaatal, wherein the personal devotion to God was written in the form of devotional poems. Vishnu, Shiva and Murugan were mentioned gods. These works are therefore the earliest evidence of monotheistic Bhakti traditions, preceding the large bhakti movement, which was given great attention in later times.

التجارة الهندية مع أفريقيا

During the time of the Roman Empire, trade took place between India and east Africa, and there is archaeological evidence of small Indian presence in Zanzibar, Zimbabwe, Madagascar, and the coastal parts of Kenya along with the Swahili coast,[76][77] but no conversion to Hinduism took place.[77][78]

المستعمرة الهندوسية في الشرق الأوسط (المشرق)

Armenian historian Zenob Glak (300-350 CE) said "there was an Indian colony in the canton of Taron on the upper Euphrates, to the west of Lake Van, as early as the second century B.C.[79] The Indians had built there two temples containing images of gods about 18 and 22 feet high."[79]

"العصر الذهبي" للهند (Gupta and Pallava period) (c. 320–650 CE)

During this period, power was centralised, along with a growth of near distance trade, standardization of legal procedures, and general spread of literacy.[80] Mahayana Buddhism flourished, but orthodox Brahmana culture began to be rejuvenated by the patronage of the Gupta Dynasty,[81] who were Vaishnavas.[82] The position of the Brahmans was reinforced,[80] the first Hindu temples dedicated to the gods of the Hindu deities, emerged during the late Gupta age.[80][note 12] During the Gupta reign the first Puranas were written,[83][note 13] which were used to disseminate "mainstream religious ideology amongst pre-literate and tribal groups undergoing acculturation".[83] The Guptas patronised the newly emerging Puranic religion, seeking legitimacy for their dynasty.[82] The resulting Puranic Hinduism, differed markedly from the earlier Brahmanism of the Dharmasastras and the smritis.[83]

According to P. S. Sharma, "the Gupta and Harsha periods form really, from the strictly intellectual standpoint, the most brilliant epocha in the development of Indian philosophy", as Hindu and Buddhist philosophies flourished side by side.[84] Charvaka, the atheistic materialist school, came to the fore in North India before the 8th century CE.[85]

إمبراطوريتا گوپتا وپالاڤا

The Gupta period (4th to 6th centuries) saw a flowering of scholarship, the emergence of the classical schools of Hindu philosophy, and of classical Sanskrit literature in general on topics ranging from medicine, veterinary science, mathematics, to astrology and astronomy and astrophysics. The famous Aryabhata and Varāhamihira belong to this age. The Gupta established a strong central government which also allowed a degree of local control. Gupta society was ordered in accordance with Hindu beliefs. This included a strict caste system, or class system. The peace and prosperity created under Gupta leadership enabled the pursuit of scientific and artistic endeavors.

The Pallavas (4th to 9th centuries) were, alongside the Guptas of the North, patronisers of Sanskrit in the South of the Indian subcontinent. The Pallava reign saw the first Sanskrit inscriptions in a script called Grantha. The Pallavas used Dravidian architecture to build some very important Hindu temples and academies in Mahabalipuram, Kanchipuram and other places; their rule saw the rise of great poets, who are as famous as Kalidasa.

During early Pallavas period, there are different connexions to Southeast Asian and other countries. Due to it, in the Middle Ages, Hinduism became the state religion in many kingdoms of Asia, the so-called Greater India—from Afghanistan (Kabul) in the West and including almost all of Southeast Asia in the East (Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Philippines)—and only by the 15th century was near everywhere supplanted by Buddhism and Islam.[86][87][88]

The practice of dedicating temples to different deities came into vogue followed by fine artistic temple architecture and sculpture (see Vastu shastra).

معبد الساحل الهندوسي (موقع تراث عالمي لليونسكو) في ماملاپورم بناه ناراسيمهاڤارمان الثاني

نزول الگنج، وتُعرف أيضاً بإسم كفارة أرجونا، في مهاباليپورم، هو أحد أكبر النقوش الصخرية البارزة في آسيا وتعرض العديد من الأساطير الهندوسية.

Bhakti

This period saw the emergence of the Bhakti movement. The Bhakti movement was a rapid growth of bhakti beginning in Tamil Nadu in Southern India with the Saiva Nayanars (4th to 10th centuries CE)[89] and the Vaisnava Alvars (3rd to 9th centuries CE) who spread bhakti poetry and devotion throughout India by the 12th to 18th centuries CE.[90][89]

التوسع في جنوب شرق آسيا

Angkor Wat in Cambodia is one of the largest Hindu monuments in the world. It is one of hundreds of ancient Hindu temples in Southeast Asia.

Prambanan in Java is a Hindu temple complex dedicated to Trimurti. It was built during the Sanjaya dynasty of Mataram Kingdom.

Hoà Lai Towers in Ninh Thuận, Vietnam, a Hindu temple complex built in the 9th century by the Champa Kingdom of Panduranga.

Pura Besakih, the holiest temple of Hindu religion in Bali.

Hindu influences reached the Indonesian Archipelago as early as the first century.[91] At this time, India started to strongly influence Southeast Asian countries. Trade routes linked India with southern Burma, central and southern Siam, lower Cambodia and southern Vietnam and numerous urbanised coastal settlements were established there.

For more than a thousand years, Indian Hindu/Buddhist influence was, therefore, the major factor that brought a certain level of cultural unity to the various countries of the region. The Pali and Sanskrit languages and the Indian script, together with Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, Brahmanism and Hinduism, were transmitted from direct contact as well as through sacred texts and Indian literature, such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata epics.

From the 5th to the 13th century, South-East Asia had very powerful Indian colonial empires and became extremely active in Hindu and Buddhist architectural and artistic creation. The Sri Vijaya Empire to the south and the Khmer Empire to the north competed for influence.

Langkasuka (-langkha Sanskrit for "resplendent land" -sukkha of "bliss") was an ancient Hindu kingdom located in the Malay Peninsula. The kingdom, along with Old Kedah settlement, are probably the earliest territorial footholds founded on the Malay Peninsula. According to tradition, the founding of the kingdom happened in the 2nd century; Malay legends claim that Langkasuka was founded at Kedah, and later moved to Pattani.

From the 5th to 15th centuries Sri Vijayan empire, a maritime empire centred on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia, had adopted Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism under a line of rulers named the Sailendras. The Empire of Sri Vijaya declined due to conflicts with the Chola rulers of India. The Majapahit Empire succeeded the Singhasari empire. It was one of the last and greatest Hindu empires in maritime Southeast Asia.

Funan was a pre-Angkor Cambodian kingdom, located around the Mekong delta, probably established by Mon-Khmer settlers speaking an Austroasiatic language. According to reports by two Chinese envoys, K'ang T'ai and Chu Ying, the state was established by an Indian Brahmin named Kaundinya, who in the 1st century CE was given instruction in a dream to take a magic bow from a temple and defeat a Khmer queen, Soma. Soma, the daughter of the king of the Nagas, married Kaundinya and their lineage became the royal dynasty of Funan. The myth had the advantage of providing the legitimacy of both an Indian Brahmin and the divinity of the cobras, who at that time were held in religious regard by the inhabitants of the region.

The kingdom of Champa (or Lin-yi in Chinese records) controlled what is now south and central Vietnam from approximately 192 through 1697. The dominant religion of the Cham people was Hinduism and the culture was heavily influenced by India.

Later, from the 9th to the 13th century, the Mahayana Buddhist and Hindu Khmer Empire dominated much of the South-East Asian peninsula. Under the Khmer, more than 900 temples were built in Cambodia and in neighboring Thailand. Angkor was at the centre of this development, with a temple complex and urban organisation able to support around one million urban dwellers. The largest temple complex of the world, Angkor Wat, stands here; built by the king Vishnuvardhan.

Late-Classical Hinduism – Puranic Hinduism (c. 650–1200 CE)

After the end of the Gupta Empire and the collapse of the Harsha Empire, power became decentralised in India. Several larger kingdoms emerged, with "countless vasal states".[93][note 14] The kingdoms were ruled via a feudal system. Smaller kingdoms were dependent on the protection of the larger kingdoms. "The great king was remote, was exalted and deified",[93] as reflected in the Tantric Mandala, which could also depict the king as the centre of the mandala.[94]

The disintegration of central power also lead to regionalisation of religiosity, and religious rivalry.[95][note 15] Local cults and languages were enhanced, and the influence of "Brahmanic ritualistic Hinduism"[95] was diminished.[95] Rural and devotional movements arose, along with Shaivism, Vaisnavism, Bhakti and Tantra,[95] though "sectarian groupings were only at the beginning of their development".[95] Religious movements had to compete for recognition by the local lords.[95] Buddhism lost its position after the 8th century, and began to disappear in India.[95] This was reflected in the change of puja-ceremonies at the courts in the 8th century, where Hindu gods replaced the Buddha as the "supreme, imperial deity".[note 16]

Puranic Hinduism

The Brahmanism of the Dharmaśāstra and the smritis underwent a radical transformation at the hands of the Purana composers, resulting in the rise of Puranic Hinduism,[83] "which like a colossus striding across the religious firmanent soon came to overshadow all existing religions".[98] Puranic Hinduism was a "multiplex belief-system which grew and expanded as it absorbed and synthesised polaristic ideas and cultic traditions".[98] It was distinguished from its Vedic Smarta roots by its popular base, its theological and sectarian pluralism, its Tantric veneer, and the central place of bhakti.[98][note 17]

The early mediaeval Puranas were composed to disseminate religious mainstream ideology among the pre-literate tribal societies undergoing acculturation.[83] With the breakdown of the Gupta empire, gifts of virgin waste-land were heaped on brahmanas,[99][100] to ensure profitable agrarian exploitation of land owned by the kings,[99] but also to provide status to the new ruling classes.[99] Brahmanas spread further over India, interacting with local clans with different religions and ideologies.[99] The Brahmanas used the Puranas to incorporate those clans into the agrarian society and its accompanying religion and ideology.[99] According to Flood, "[t]he Brahmans who followed the puranic religion became known as smarta, those whose worship was based on the smriti, or pauranika, those based on the Puranas."[101] Local chiefs and peasants were absorbed into the varna, which was used to keep "control over the new kshatriyas and shudras."[102]

The Brahmanic group was enlarged by incorporating local subgroups, such as local priests.[99] This also lead to stratification within the Brahmins, with some Brahmins having a lower status than other Brahmins.[99] The use of caste worked better with the new Puranic Hinduism than with the Sramanic sects.[102] The Puranic texts provided extensive genealogies which gave status to the new kshatriyas.[102] Buddhist myths pictured government as a contract between an elected ruler and the people.[102] And the Buddhist chakkavatti[note 18] "was a distinct concept from the models of conquest held up to the kshatriyas and the Rajputs".[102]

Many local religions and traditions were assimilated into puranic Hinduism. Vishnu and Shiva emerged as the main deities, together with Sakti/Deva.[104] Vishnu subsumed the cults of Narayana, Jagannaths, Venkateswara "and many others".[104] Nath:

[S]ome incarnations of Vishnu such as Matsya, Kurma, Varaha and perhaps even Nrsimha helped to incorporate certain popular totem symbols and creation myths, especially those related to wild boar, which commonly permeate preliterate mythology, others such as Krsna and Balarama became instrumental in assimilating local cults and myths centering around two popular pastoral and agricultural gods.[105]

The transformation of Brahmanism into Pauranic Hinduism in post-Gupta India was due to a process of acculturation. The Puranas helped establish a religious mainstream among the pre-literate tribal societies undergoing acculturation. The tenets of Brahmanism and of the Dharmashastras underwent a radical transformation at the hands of the Purana composers, resulting in the rise of a mainstream "Hinduism" that overshadowed all earlier traditions.[99]

Bhakti movement

Rama and Krishna became the focus of a strong bhakti tradition, which found expression particularly in the Bhagavata Purana. The Krishna tradition subsumed numerous Naga, yaksa and hill and tree-based cults.[106] Siva absorbed local cults by the suffixing of Isa or Isvara to the name of the local deity, for example, Bhutesvara, Hatakesvara, Chandesvara.[104] In 8th-century royal circles, the Buddha started to be replaced by Hindu gods in pujas.[note 19] This also was the same period of time the Buddha was made into an avatar of Vishnu.[108]

The first documented bhakti movement was founded by Karaikkal Ammaiyar. She wrote poems in Tamil about her love for Shiva and probably lived around the 6th century CE. The twelve Alvars who were Vaishnavite devotees and the sixty-three Nayanars who were Shaivite devotees nurtured the incipient bhakti movement in Tamil Nadu.

During the 12th century CE in Karnataka, the Bhakti movement took the form of the Virashaiva movement. It was inspired by Basavanna, a Hindu reformer who created the sect of Lingayats or Shiva bhaktas. During this time, a unique and native form of Kannada literature-poetry called Vachanas was born.

Advaita Vedanta

The early Advaitin Gaudapada (6th-7th c. CE) was influenced by Buddhism.[110][111][112][113] Gaudapda took over the Buddhist doctrines that ultimate reality is pure consciousness (vijñapti-mātra)[114] and "that the nature of the world is the four-cornered negation".[114] Gaudapada "wove [both doctrines] into a philosophy of the Mandukya Upanishad, which was further developed by Shankara".[111] Gaudapada also took over the Buddhist concept of "ajāta" from Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka philosophy.[112][113] Shankara succeeded in reading Gaudapada's mayavada[115][note 20] into Badarayana's Brahma Sutras, "and give it a locus classicus",[115] against the realistic strain of the Brahma Sutras.[115]

Shankara (8th century CE) was a scholar who synthesized and systematized Advaita Vedanta views which already existed at his lifetime.[116][117][118][web 8] Shankara propounded a unified reality, in which the innermost self of a person (atman) and the supernatural power of the entire world (brahman) are one and the same. Perceiving the changing multiplicity of forms and objects as the final reality is regarded as maya, "illusion," obscuring the unchanging ultimate reality of brahman.[119][120][121][122]

While Shankara has an unparalleled status in the history of Advaita Vedanta, Shankara's early influence in India is doubtful.[123] Until the 11th century, Vedanta itself was a peripheral school of thought,[124] and until the 10th century Shankara himself was overshadowed by his older contemporary Maṇḍana Miśra, who was considered to be the major representative of Advaita.[125][126]

Several scholars suggest that the historical fame and cultural influence of Shankara and Advaita Vedanta grew only centuries later, during the era of the Muslim invasions and consequent devastation of India,[123][127][128] due to the efforts of Vidyaranya (14th c.), who created legends to turn Shankara into a "divine folk-hero who spread his teaching through his digvijaya ("universal conquest") all over India like a victorious conqueror."[129][130]

Shankara's position was further established in the 19th an 20th-century, when neo-Vedantins and western Orientalists elevated Advaita Vedanta "as the connecting theological thread that united Hinduism into a single religious tradition."[131] Advaita Vedanta has acquired a broad acceptance in Indian culture and beyond as the paradigmatic example of Hindu spirituality,[132] Shankara became "an iconic representation of Hindu religion and culture," despite the fact that most Hindus do not adhere to Advaita Vedanta.[133]

التواصل مع فارس والرافدين

Hindu and also Buddhist religious and secular learning had first reached Persia in an organised manner in the 6th century, when the Sassanid Emperor Khosrow I (531–579) deputed Borzuya the physician as his envoy, to invite Indian and Chinese scholars to the Academy of Gondishapur. Burzoe had translated the Sanskrit Panchatantra. His Pahlavi version was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa' under the title of Kalila and Dimna or The Fables of Bidpai.[134]

Under the Abbasid caliphate, Baghdad had replaced Gundeshapur as the most important centre of learning in the then vast Islamic Empire, wherein the traditions, as well as scholars of the latter, flourished. Hindu scholars were invited to the conferences on sciences and mathematics held in Baghdad.[135]

Medieval and early modern periods (c. 1200–1850 CE)

Muslim rule

Though Islam came to the Indian subcontinent in the early 7th century with the advent of Arab traders, it started impacting Indian religions after the 10th century, and particularly after the 12th century with the establishment and then expansion of Islamic rule.[136][137] Will Durant calls the Muslim conquest of India "probably the bloodiest story in history".[138] During this period, Buddhism declined rapidly while Hinduism faced military-led and Sultanates-sponsored religious violence.[138][139] There was a widespread practice of raids, seizure and enslavement of families of Hindus, who were then sold in Sultanate cities or exported to Central Asia.[140][141] Some texts suggest a number of Hindus were forcibly converted to Islam.[142][143] Starting with the 13th century, for a period of some 500 years, very few texts, from the numerous written by Muslim court historians, mention any "voluntary conversions of Hindus to Islam", suggesting the insignificance and perhaps rarity of such conversions.[143] Typically enslaved Hindus converted to Islam to gain their freedom.[144] There were occasional exceptions to religious violence against Hinduism. Akbar, for example, recognized Hinduism, banned enslavement of the families of Hindu war captives, protected Hindu temples, and abolished discriminatory Jizya (head taxes) against Hindus.[140][145] However, many Muslim rulers of Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire, before and after Akbar, from the 12th to 18th centuries, destroyed Hindu temples[web 9][146][web 10][note 21] and persecuted non-Muslims. As noted by Alain Daniélou:

From the time Muslims started arriving, around 632 AD, the history of India becomes a long, monotonous series of murders, massacres, spoliations, and destructions. It is, as usual, in the name of 'a holy war' of their faith, of their sole God, that the barbarians have destroyed civilizations, wiped out entire races.[147]

The image, in the chapter on India in Hutchison's Story of the Nations edited by James Meston, depicts the Muslim Turkic general Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khalji's massacre of Buddhist monks in Bihar, India. Khaliji destroyed the Nalanda and Vikramshila universities during his raids across North Indian plains, massacring many Buddhist and Brahmin scholars.[148]

The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was destroyed by the army of Delhi Sultan Qutb ud-Din Aibak.[149]

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[149]

Bhakti Vedanta

Teachers such as Ramanuja, Madhva, and Chaitanya aligned the Bhakti movement with the textual tradition of Vedanta, which until the 11th century was only a peripheral school of thought,[124] while rejecting and opposing the abstract notions of Advaita. Instead, they promoted emotional, passionate devotion towards the more accessible Avatars, especially Krishna and Rama.[136][150]

Ramanuja is one of the most important exponents of the Sri Vaishnavism tradition within Hinduism, depicted with Vaishnava Tilaka and Varadraja (Vishnu) statue.[151]

Madhvacharya, is chief proponent of Sadh Vaishnavism tradition and Tattvavada (Dvaita) school of Vedanta within Hinduism, depicted with Vaishnava Gopichandana Urdhva Pundra and Gnana Mudra (or Jnana Mudra or Jana Mudra), a symbol of knowledge and wisdom.[152]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, chief proponent of the Achintya Bheda Abheda and Gaudiya Vaishnavism tradition within Hinduism, and Nityananda, is shown performing a 'kirtan' in the streets of Nabadwip, Bengal.[web 11]

Modern Hinduism (after c. 1850 CE)

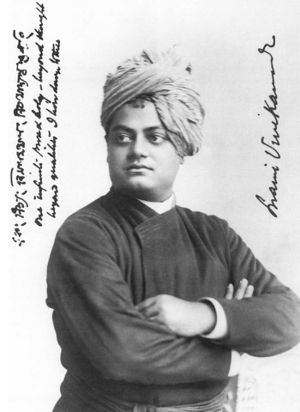

With the onset of the British Raj, the colonization of India by the British, there also started a Hindu Renaissance in the 19th century, which profoundly changed the understanding of Hinduism in both India and the west.[155] Indology as an academic discipline of studying Indian culture from a European perspective was established in the 19th century, led by scholars such as Max Müller and John Woodroffe. They brought Vedic, Puranic and Tantric literature and philosophy to Europe and the United States. Western orientalist searched for the "essence" of the Indian religions, discerning this in the Vedas,[156] and meanwhile creating the notion of "Hinduism" as a unified body of religious praxis[132] and the popular picture of 'mystical India'.[132][155] This idea of a Vedic essence was taken over by Hindu reform movements as the Brahmo Samaj, which was supported for a while by the Unitarian Church,[157] together with the ideas of Universalism and Perennialism, the idea that all religions share a common mystic ground.[158] This "Hindu modernism", with proponents like Vivekananda, Aurobindo, Rabindranath and Radhakrishnan, became central in the popular understanding of Hinduism.[159][160][161][162][132]

الإحياء الهندوسي

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ See:

- "أقدم ديانة":

- Fowler (1997, p. 1): "ربما أقدم ديانة في العالم"

- Gellman & Hartman (2011): "الهندوسية، أقدم ديانة في العالم"

- Stevens (2001, p. 191): "الهندوسية، أقدم ديانة في العالم"

- "أقدم ديانة حية" (Sarma 1987, p. 3)

- "أقدم ديانة رئيسية حية" في العالم (Merriam-Webster 2000, p. 751; Klostermaier 2007, p. 1)

- Laderman (2003, p. 119): "world's oldest living civilisation and religion"

- Turner (1996-B, p. 359): "It is also recognized as the oldest major religion in the world"

- Urreligion, Shamanism, Animism, Ancestor worship for some of the oldest forms of religion

- Sarnaism and Sanamahism, Indian Tribal religions connected to the earliest migrations into India

- Australian Aboriginal mythology, one of the oldest surviving religions in the world.

- "أقدم ديانة":

- ^ وبين جذورها نجد:

- الديانة الڤيدية (Flood 1996, p. 16) من الفترة الڤيدية المتأخرة و وتركيزها على مكانة البراهمان (Samuel 2010, pp. 48–53)، ولكن أيضاً

- the religions of the Indus Valley Civilisation (Narayanan 2009, p. 11, Lockard 2007, p. 52, Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 3, Jones & Ryan 2006, p. xviii),

- the Sramana or renouncer traditions (Gomez 2013, p. 42, Flood 1996, p. 16) of north-east India (Gomez 2013, p. 42), and

- "popular or local traditions" (Flood 1996, p. 16)

- ^ There is no exact dating possible for the beginning of the Vedic period. Witzel mentions a range between 1900 and 1400 BCE.[9] Flood mentions 1500 BCE.[10]

- ^ See also Tanvir Anjum, Temporal Divides: A Critical Review of the Major Schemes of Periodization in Indian History.

- ^ Different periods are designated as "classical Hinduism":

- Smart (2003, p. 52) calls the period between 1000 BCE and 100 CE "pre-classical". It is the formative period for the Upanishads and Brahmanism[subnote 1] Jainism and Buddhism. For Smart, the "classical period" lasts from 100 to 1000 CE, and coincides with the flowering of "classical Hinduism" and the flowering and deterioration of Mahayana-buddhism in India.

- For Michaels (2004, pp. 36, 38), the period between 500 BCE and 200 BCE is a time of "Ascetic reformism", whereas the period between 200 BCE and 1100 CE is the time of "classical Hinduism", since there is "a turning point between the Vedic religion and Hindu religions".

- Muesse (2003, p. 14) discerns a longer period of change, namely between 800 BCE and 200 BCE, which he calls the "Classical Period". According to Muesse, some of the fundamental concepts of Hinduism, namely karma, reincarnation and "personal enlightenment and transformation", which did not exist in the Vedic religion, developed in this time.

- Stein (2010, p. 107) The Indian History Congress, formally adopted 1206 CE as the date medieval India began.

- ^ Doniger 2010, p. 66: "Much of what we now call Hinduism may have had roots in cultures that thrived in South Asia long before the creation of textual evidence that we can decipher with any confidence. Remarkable cave paintings have been preserved from Mesolithic sites dating from c. 30,000 BCE in Bhimbetka, near present-day Bhopal, in the Vindhya Mountains in the province of Madhya Pradesh."[subnote 2]

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. xvii: "Some practices of Hinduism must have originated in Neolithic times (c. 4000 BCE). The worship of certain plants and animals as sacred, for instance, could very likely have very great antiquity. The worship of goddesses, too, a part of Hinduism today, may be a feature that originated in the Neolithic."

- ^ Mallory 1989, p. 38f. The separation of the early Indo-Aryans from the Proto-Indo-Iranian stage is dated to roughly 1800 BCE in scholarship.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMichaels_decline - ^ Klostermaier 2007, p. 55: "Kautas, a teacher mentioned in the Nirukta by Yāska (ca. 500 BCE), a work devoted to an etymology of Vedic words that were no longer understood by ordinary people, held that the word of the Veda was no longer perceived as meaningful "normal" speech but as a fixed sequence of sounds, whose meaning was obscure beyond recovery."

- ^ Klostermaier: "Brahman, derived from the root bŗh = to grow, to become great, was originally identical with the Vedic word, that makes people prosper: words were the principal means to approach the gods who dwelled in a different sphere. It was not a big step from this notion of "reified speech-act" to that "of the speech-act being looked at implicitly and explicitly as a means to an end." Klostermaier 2007, p. 55 quotes Madhav M. Deshpande (1990), Changing Conceptions of the Veda: From Speech-Acts to Magical Sounds, p. 4.

- ^ Michaels (2004, p. 40) mentions the Durga temple in Aihole and the Visnu Temple in Deogarh. Michell (1977, p. 18) notes that earlier temples were built of timber, brick and plaster, while the first stone temples appeared during the period of Gupta rule.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPuranas-date - ^ Michaels (2004, p. 41):

- In the east the Pala Empire (770–1125 CE),

- in the west and north the Gurjara-Pratihara (7th–10th century),

- in the southwest the Rashtrakuta Dynasty (752–973),

- in the Dekkhan the Chalukya dynasty (7th–8th century),

- and in the south the Pallava dynasty (7th–9th century) and the Chola dynasty (9th century).

- ^ McRae (2003): This resembles the development of Chinese Chán during the An Lu-shan rebellion and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period (907–960/979), during which power became decentralised end new Chán-schools emerged.

- ^ Inden (1998, p. 67): "Before the eighth century, the Buddha was accorded the position of universal deity and ceremonies by which a king attained to imperial status were elaborate donative ceremonies entailing gifts to Buddhist monks and the installation of a symbolic Buddha in a stupa ... This pattern changed in the eighth century. The Buddha was replaced as the supreme, imperial deity by one of the Hindu gods (except under the Palas of eastern India, the Buddha's homeland) ... Previously the Buddha had been accorded imperial-style worship (puja). Now as one of the Hindu gods replaced the Buddha at the imperial centre and pinnacle of the cosmo-political system, the image or symbol of the Hindu god comes to be housed in a monumental temple and given increasingly elaborate imperial-style puja worship."

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMichaels-legacy - ^ Thapar (2003, p. 325): The king who ruled not by conquest but by setting in motion the wheel of law.

- ^ Inden: "before the eighth century, the Buddha was accorded the position of universal deity and ceremonies by which a king attained to imperial status were elaborate donative ceremonies entailing gifts to Buddhist monks and the installation of a symbolic Buddha in a stupa ... This pattern changed in the eighth century. The Buddha was replaced as the supreme, imperial deity by one of the Hindu gods (except under the Palas of eastern India, the Buddha's homeland) ... Previously the Buddha had been accorded imperial-style worship (puja). Now as one of the Hindu gods replaced the Buddha at the imperial centre and pinnacle of the cosmo-political system, the image or symbol of the Hindu god comes to be housed in a monumental temple and given increasingly elaborate imperial-style puja worship."[107]

- ^ The term "mayavada" is still being used, in a critical way, by the Hare Krshnas. See[web 4][web 5][web 6][web 7]

- ^ See also "Aurangzeb, as he was according to Mughal Records"; more links at the bottom of that page; for Muslim historian's record on major Hindu temple destruction campaigns, from 1193 to 1729 AD, see خطأ: الوظيفة "harvard_core" غير موجودة.

ملاحظات فرعية

الهامش

- ^ Brodd 2003.

- ^ أ ب Lockard 2007, p. 50.

- ^ أ ب Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Samuel 2010, p. 193.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 16.

- ^ Narayanan 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Osborne 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 32-36.

- ^ Witzel 1995, p. 3-4.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 21.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 38.

- ^ أ ب Michaels 2004.

- ^ Blackwell's History of India; Stein 2010, page 107

- ^ Some Aspects of Muslim Administration, Dr. R.P.Tripathi, 1956, p.24

- ^ Thapar 1978, pp. 19–20.

- ^ أ ب ت Thapar 1978, p. 19.

- ^ Thapar 1978, p. 20.

- ^ أ ب Mathpal, Yashodhar (1984). Prehistoric Painting of Bhimbetka. Abhinav Publications. p. 220. ISBN 9788170171935.

- ^ أ ب Tiwari, Shiv Kumar (2000). Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings. Sarup & Sons. p. 189. ISBN 9788176250863.

- ^ أ ب Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka (PDF). UNESCO. 2003. p. 16.

- ^ أ ب Mithen, Steven (2011). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000 – 5000 BC. Orion. p. 524. ISBN 978-1-78022-259-2.

- ^ أ ب Javid, Ali; Jāvīd, ʻAlī; Javeed, Tabassum (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-87586-484-6.

- ^ https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/925.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ Basham 1967.

- ^ Frederick J. Simoons (1998). Plants of life, plants of death. p. 363.

- ^ Ranbir Vohra (2000). The Making of India: A Historical Survey. M.E. Sharpe. p. 15.

- ^ Grigoriĭ Maksimovich Bongard-Levin (1985). Ancient Indian Civilization. Arnold-Heinemann. p. 45.

- ^ Rosen 2006, p. 45.

- [[#cite_ref-FOOTNOTESrinivasan1997[[تصنيف:مقالات_بالمعرفة_بحاجة_لذكر_رقم_الصفحة_بالمصدر_from_March_2021]][[Category:Articles_with_invalid_date_parameter_in_template]]<sup_class="noprint_Inline-Template_"_style="white-space:nowrap;">[<i>[[المعرفة:Citing_sources|<span_title="هذه_المقولة_تحتاج_مرجع_إلى_صفحة_محددة_أو_نطاق_من_الصفحات_تظهر_فيه_المقولة'"`UNIQ--nowiki-00000068-QINU`"'_(March_2021)">صفحة مطلوبة</span>]]</i>]</sup>_62-0|^]] Srinivasan 1997, p. [صفحة مطلوبة].

- ^ Mahadevan, Iravatham (2006). A Note on the Muruku Sign of the Indus Script in light of the Mayiladuthurai Stone Axe Discovery. harappa.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg; Kak, Subhash; Frawley, David (2001). In Search of the Cradle of Civilization:New Light on Ancient India. Quest Books. p. 121. ISBN 0-8356-0741-0.

- ^ Clark, Sharri R. (2007). The social lives of figurines: recontextualizing the third millennium BC terracotta figurines from Harappa, Pakistan (PhD). Harvard.

- ^ Thapar, Romila, Early India: From the Origins to 1300, London, Penguin Books, 2002

- ^ McIntosh, Jane. (2008) The Ancient Indus Valley : New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 84,276

- ^ Catherine Jarrige; John P. Gerry; Richard H. Meadow, eds. (1992). South Asian Archaeology, 1989: Papers from the Tenth International Conference of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, Musée National Des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris, France, 3-7 July 1989. Prehistory Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-881094-03-6.

An anthropomorphic figure has knelt in front of a fig tree, with hands raised in respectful salutation, prayer or worship. This reverence suggests the divinity of its object, another anthropomorphic figure standing inside the fig tree. In the ancient Near East, the gods and goddesses, as well as their earthly representatives, the divine kings and queens functioning as high priests and priestesses, were distinguished by a horned crown. A similar crown is worn by the two anthropomorphic figures in the fig deity seal. Among various tribal people of India, horned head-dresses are worn by priests on sacrificial occasions.

- ^ Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ The Indus Script. Text, Concordance And Tables Iravathan Mahadevan. p. 139.

- ^ Littleton, C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology. Marshall Cavendish. p. 732. ISBN 978-0-7614-7565-1.

- ^ Marshall 1996, p. 389.

- ^ Singh. The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination. Pearson Education India. p. 35. ISBN 9788131717530.

- ^ Pletcher, Kenneth (2010). The History of India. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 60.

- ^ Kramer 1986.

- ^ David Christian (1 September 2011). Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. University of California Press. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-520-95067-2.

- ^ Singh 2008, pp. 206–.

- ^ Sahoo, P. C. (1994). "On the Yṻpa in the Brāhmaṇa Texts". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 54/55: 175–183. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 42930469.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Yves (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- ^ Krishnananda. Swami. A Short History of Religious and Philosophic Thought in India, Divine Life Society. p. 21

- ^ Holdrege 2004, p. 215.

- ^ Panikkar 2001, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Day, Terence P. (1982). The Conception of Punishment in Early Indian Literature. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 42–45. ISBN 0-919812-15-5.

- ^ Duchesne-Guillemin 1963, p. 46.

- ^ Neusner 2009, p. 183.

- ^ Melton & Baumann 2010, p. 1324.

- ^ Mahadevan, T. M. P (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, p. 57

- ^ Fowler, Jeaneane D. (1 February 2012). The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students. Sussex Academic Press. pp. xxii–xxiii. ISBN 978-1-84519-346-1.

- ^ أ ب Heesterman 2005, pp. 9552–9553.

- ^ Witzel 1995.

- ^ Samuel 2010.

- ^ Basham 1989, pp. 74–75.

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBIKA - ^ أ ب Flood 1996, p. 82.

- ^ Michaels 2004, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Bronkhorst 2017, p. 363.

- ^ Klostermaier 2007, p. 55.

- ^ Bronkhorst 2016, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Michaels 2014.

- ^ Staal, J. F. 1961. Nambudiri Veda Recitations Gravenhage.

- ^ Staal, J. F. 1983. Agni: The Vedic ritual of the fire altar. 2 vols. Berkeley.

- ^ Staal, Frits (1988), Universals: studies in Indian logic and linguistics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-76999-2

- ^ Singh 2008, pp. 436–438.

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence, 2016.

- ^ Srinivasan 1997, p. 215.

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- ^ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1967, p. xviii–xxi

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2008, pp. 10–12.

- ^ أ ب W.H. Ingrams (1967), Zanzibar: Its History and Its People, ISBN 978-0714611020, Routledge, pp. 33–35

- ^ Prabha Bhardwaj, Hindus Stand Strong In Ancient Tanzania Hinduism Today (1996)

- ^ أ ب Majumdar, R. C. (1968). The History and Culture of the Indian People. Vol. II: The Age of Imperial Unity. pp. 633–634.

- ^ أ ب ت Michaels 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Nakamura 2004, p. 687.

- ^ أ ب Thapar 2003, p. 325.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Vijay Nath 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Sharma, Peri Sarveswara (1980). Anthology of Kumārilabhaṭṭa's Works. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. p. 5.

- ^ Bhattacharya 2011, p. 65.

- ^ Cœdès 1968.

- ^ Pande 2006.

- ^ "The spread of Hinduism in Southeast Asia and the Pacific". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ أ ب Embree 1988, p. 342.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 131.

- ^ Jan Gonda, The Indian Religions in Pre-Islamic Indonesia and their survival in Bali, in Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Religions, p. 1, في كتب گوگل, pp. 1–54

- ^ K. D. Bajpai (2006). History of Gopāchala. Bharatiya Jnanpith. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-263-1155-2.

- ^ أ ب Michaels 2004, p. 41.

- ^ White 2000, pp. 25–28.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Michaels 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Sara Schastok (1997), The Śāmalājī Sculptures and 6th Century Art in Western India, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004069411, pp. 77–79, 88

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 111–119.

- ^ أ ب ت Vijay Nath 2001, p. 20.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Vijay Nath 2001.

- ^ Thapar 2003, pp. 325, 487.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 113.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Thapar 2003, p. 487.

- ^ Kuwayama 1976, p. 405: "It is not therefore possible to attribute these pieces to the Hindu Shahi period. They should be attributed to the Shahi period before the Hindu Shahis originated by the Brahman wazir Kallar, that is, the Turki Shahis."

Kuwayama 1976, p. 407: "According to the above sources, Brahmanism and Buddhism are properly supposed to have coexisted especially during the 7th-8th centuries A.D. just before the Muslim hegemony. The marble sculptures from eastern Afghanistan should not be attributed to the period of the Hindu Shahis but to that of the Turki Shahis." - ^ أ ب ت Vijay Nath 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Vijay Nath 2001, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Vijay Nath 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Inden 1998, pp. 55, 67.

- ^ Holt, John. The Buddhist Visnu. Columbia University Press, 2004, p. 12, 15 "The replacement of the Buddha as the 'cosmic person' within the mythic ideology of Indian kingship, as we shall see shortly, occurred at about the same time the Buddha was incorporated and subordinated within the Brahmanical cult of Visnu."

- ^ Johannes de Kruijf and Ajaya Sahoo (2014), Indian Transnationalism Online: New Perspectives on Diaspora, ISBN 978-1472419132, p. 105, Quote: "In other words, according to Adi Shankara's argument, the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta stood over and above all other forms of Hinduism and encapsulated them. This then united Hinduism; ... Another of Adi Shankara's important undertakings which contributed to the unification of Hinduism was his founding of a number of monastic centers."

- ^ Sharma 2000, pp. 60–64.

- ^ أ ب Raju 1992, pp. 177–178.

- ^ أ ب Renard 2010, p. 157.

- ^ أ ب Comans 2000, pp. 35–36.

- ^ أ ب Raju 1992, p. 177.

- ^ أ ب ت Sharma 2000, p. 64.

- ^ Nakamura 2004, p. 678.

- ^ Sharma 1962, p. vi.

- ^ Comans 2000, p. 163.

- ^ Menon, Y.K (January 2004). The Mind of Adi Shankaracharya. Repro Knowledgcast Ltd. ISBN 817224214X.

- ^ Campagna, Federico. Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality. Bloomsbury. p. 124. ISBN 1-350-04402-4.

- ^ Shankara, Adi. Nirguna Manasa Puja: Worship of the Attributeless. Society of Abidance in Truth. p. vii.

- ^ Paranjpe, Anand C (2006). Self and Identity in Modern Psychology and Indian Thought. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-306-47151-3.

- ^ أ ب Hacker 1995, p. 29–30.

- ^ أ ب Nicholson 2010, p. 157; 229 note 57.

- ^ King 2002, p. 128.

- ^ Roodurmum 2002, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Blake Michael 1992, p. 60–62 with notes 6, 7 and 8.

- ^ Nicholson 2010, pp. 178–183.

- ^ Hacker 1995, p. 29.

- ^ Kulke & Rothermund 1998, p. 177.

- ^ King 2001, p. 129.

- ^ أ ب ت ث King 1999.

- ^ King 2001, p. 129-130.

- ^ Francisco Rodríguez Adrados; Lukas de Blois; Gert-Jan van Dijk (2006). Mnemosyne, Bibliotheca Classica Batava: Supplementum. BRILL. pp. 707–708. ISBN 978-90-04-11454-8.

- ^ O'Malley, Charles Donald (1970). The History of Medical Education: An International Symposium Held February 5–9, 1968. University of California Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-520-01578-4.

- ^ أ ب Basham 1999

- ^ Smith 1999, pp. 381–384.

- ^ أ ب Will Durant (1976), The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0671548001, pp. 458–472: "The Mohammedan Conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precarious thing, whose delicate complex of order and liberty, culture and peace may at any time be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within. The Hindus had allowed their strength to be wasted in internal division and war; they had adopted religions like Buddhism and Jainism, which unnerved them for the tasks of life; they had failed to organize their forces for the protection of their frontiers and their capitals."

- ^ Gaborieau 1985.

- ^ أ ب خطأ: الوظيفة "harvard_core" غير موجودة.: "In 1562 Akbar abolished the practice of enslaving the families of war captives; his son Jahangir banned sending of slaves from Bengal as tribute in lieu of cash, which had been the custom since the 14th century. These measures notwithstanding, the Mughals actively participated in slave trade with Central Asia, deporting [Hindu] rebels and subjects who had defaulted on revenue payments, following precedents inherited from Delhi Sultanate" (emphasis added?).

- ^ Wink 1991, pp. 14–16, 172–174, etc.

- ^ Sharma, Hari (1991), The real Tipu: a brief history of Tipu Sultan, Rishi publications, p. 112, https://books.google.com/books?ei=TYMYTPfXCse0rAf8-62tCg

- ^ أ ب P. Hardy (1977), "Modern European and Muslim explanations of conversion to Islam in South Asia: A preliminary survey of the literature", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, Volume 109, Issue 02, pp. 177–206

- ^ Burjor Avari (2013), Islamic Civilization in South Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415580618, pp. 66–70: "Many Hindu slaves converted to Islam and gained their liberty".

- ^ Grapperhaus 2009, p. 118.

- ^ David Ayalon (1986), Studies in Islamic History and Civilisation, BRILL, p.271;ISBN 965-264-014-X

- ^ Dipak Basu; Victoria Miroshnik (7 August 2017). India as an Organization: Volume One: A Strategic Risk Analysis of Ideals, Heritage and Vision. Springer. pp. 52ff. ISBN 978-3-319-53372-8.

- ^ Sanyal, Sanjeev (15 November 2012). Land of seven rivers: History of India's Geography. Penguin Books. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-81-8475-671-5.

- ^ أ ب Eaton 2000.

- ^ J. T. F. Jordens, "Medieval Hindu Devotionalism" in Basham 1999

- ^ Mishra, Patit Paban (2012). "Rāmānuja (ca. 1077–ca. 1157)". In Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (eds.). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. doi:10.4135/9781412997898.n598. ISBN 9780761927297.

- ^ Stoker 2011.

- ^ Georg, Feuerstein (2002), The Yoga Tradition, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 600

- ^ Clarke 2006, p. 209.

- ^ أ ب King 2002.

- ^ King 2002, p. 118.

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 114.

- ^ King 2002, pp. 119–120.

- ^ King 2002, p. 123.

- ^ Muesse 2011, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Doniger 2010, p. 18.

- ^ Jouhki 2006, pp. 10–11.

المصادر

المطبوعة

- Allchin, Frank Raymond; Erdosy, George (1995), The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, Cambridge University Press, https://books.google.com/books?id=EfZRVIjjZHYC, retrieved on 2008-11-25

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University Press

- Avari, Burjor (2013). Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A history of Muslim power and presence in the Indian subcontinent. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-58061-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ayalon, David (1986), Studies in Islamic History and Civilisation, BRILL, ISBN 965-264-014-X

- Banerji, S. C. (1992), Tantra in Bengal (Second Revised and Enlarged ed.), Delhi: Manohar, ISBN 81-85425-63-9

- Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (1989), The Origins and Development of Classical Hinduism, Oxford University Press, https://books.google.com/books?id=2aqgTYlhLikC&dq=history+of+hinduism&hl=nl&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- Basham, A.L (1999), A Cultural History of India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563921-9

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691135894

- Beversluis, Joel (2000), Sourcebook of the World's Religions: An Interfaith Guide to Religion and Spirituality (Sourcebook of the World's Religions, 3rd ed), Novato, Calif: New World Library, ISBN 1-57731-121-3

- Bhaktivedanta, A. C. (1997), Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, ISBN 0-89213-285-X, http://bhagavadgitaasitis.com/, retrieved on 14 July 2007

- Bhaskarananda, Swami (1994), The Essentials of Hinduism: a comprehensive overview of the world's oldest religion, Seattle, WA: Viveka Press, ISBN 1-884852-02-5

- Bhattacharya, Vidhushekhara (1943), Gauḍapādakārikā, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Bhattacharyya, N.N (1999), History of the Tantric Religion (Second Revised ed.), Delhi: Manohar publications, ISBN 81-7304-025-7

- Bowker, John (2000), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press

- Brodd, Jefferey (2003), World Religions, Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press, ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5

- Bryant, Edwin (2007), Krishna: A Sourcebook, Oxford University Press

- Burley, Mikel (2007), Classical Samkhya and Yoga: An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Taylor & Francis

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton University Press, https://books.google.com/books?id=FrwNcwKaUKoC&dq=Australoid+india&hl=nl&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- Chidbhavananda, Swami (1997), The Bhagavad Gita, Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam

- Clarke, Peter Bernard (2006), New Religions in Global Perspective, Routledge, p. 209, ISBN 0-7007-1185-6

- Clark, Sharri R. (2007), The social lives of figurines: recontextualising the third millennium BCE terracotta figurines from Harappa, Pakistan. Harvard PhD

- Comans, Michael (2000), The Method of Early Advaita Vedānta: A Study of Gauḍapāda, Śaṅkara, Sureśvara, and Padmapāda, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Cordaux, Richard; Weiss, Gunter; Saha, Nilmani; Stoneking, Mark (2004), "The Northeast Indian Passageway: A Barrier or Corridor for Human Migrations?", Molecular Biology and Evolution (Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution) 21: 1525–33, doi:, PMID 15128876, http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/21/8/1525, retrieved on 25 November 2008

- Cousins, L.S. (2010), Buddhism. In: "The Penguin Handbook of the World's Living Religions", Penguin, https://books.google.com/books?id=bNAJiwpmEo0C&dq=%22hindu+synthesis%22&hl=nl&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- Crangle, Edward Fitzpatrick (1994), The Origin and Development of Early Indian Contemplative Practices, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag

- Doniger, Wendy (1999), Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZP_f9icf2roC&hl=nl&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- Doniger, Wendy (2010), The Hindus: An Alternative History, Oxford University Press, https://books.google.com/books?id=nNsXZkdHvXUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=history+of+hinduism&hl=nl&sa=X&ei=JMs5UqiDD-Od0QXMkoGwBg&ved=0CEsQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20hinduism&f=false

- Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques (1963), "Heraclitus and Iran", History of Religions 3 (1): 34–49, doi:

- Eaton, Richard M. (1993), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, University of California Press, http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft067n99v9;brand=ucpress

- Eaton, Richard M. (2000a), "Temple desecration in pre-modern India. Part I", Frontline, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00islamlinks/txt_eaton_temples1.pdf

- Eaton, Richard M. (2006), "Introduction", Slavery and South Asian History, Indiana University Press 0-2533, ISBN 0-253348102

- Eliot, Sir Charles (2003), Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch, I (Reprint ed.), Munshiram Manoharlal, ISBN 81-215-1093-7

- Embree, Ainslie T. (1988), Sources of Indian Tradition. Second Edition. volume One. From the beginning to 1800, Columbia University Press

- Esposito, John (2003), "Suhrawardi Tariqah", The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195125597

- Feuerstein, Georg (2002), The Yoga Tradition, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 3-935001-06-1

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press

- Flood, Gavin (2006), The Tantric Body. The Secret Tradition of Hindu Religion, I.B Taurus

- Flood, Gavin (2008), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, John Wiley & Sons

- Fort, Andrew O. (1998), Jivanmukti in Transformation: Embodied Liberation in Advaita and Neo-Vedanta, SUNY Press

- Fowler, Jeaneane D. (1997), Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press

- Fuller, C. J. (2004), The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12048-5

- Gaborieau, Marc (June 1985), "From Al-Beruni to Jinnah: Idiom, Ritual and Ideology of the Hindu-Muslim Confrontation in South Asia", Anthropology Today (Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) 1 (3): 7–14, doi:

- Garces-Foley, Katherine (2005), Death and religion in a changing world, M. E. Sharpe

- Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1992), Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World, Volume 1, Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 9788170223740, https://books.google.com/?id=w9pmo51lRnYC&dq=first+mention+of+the+word+sindhu