حرب المحيط الهادي (1879-1884)

| War of the Pacific | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

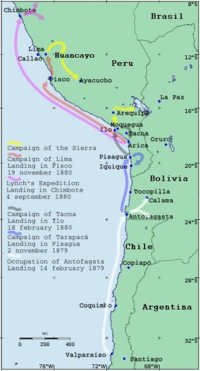

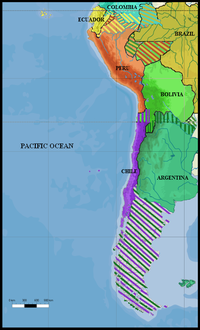

Map showing changes of territory due to the War of the Pacific. Former maps (1879) show different lines of the border between Bolivia-Peru and Bolivia-Argentina. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||||

|

Presidents of Bolivia H.Daza (1876–1879) P.J.D. de Guerra (1879) N.Campero (1879–1884) Presidents of Peru M.I.Prado (1876–1879) L. La Puerta (1879) N. de Piérola (1879–1881) F.García C. (1881) L.Montero F. (1881–1883) M.Iglesias (1882–1885) |

Presidents of Chile A.Pinto (1876–1881) D.Santa María (1881–1886) | ||||||||

| القوى | |||||||||

|

1879 (prewar) Bolivian Army: 1,687[1] Peruvian Army: 5,557[2] Peruvian Navy: 4 ironclads 7 wooden ships 2 torpedo boats[3] (Bolivia had no navy) 1880 (Bolivia not militarily active)[4] Peruvian Army: 25,000–35,000 men (Army of Lima)[5] Peruvian Navy: 3 ironclads 7 wooden ships 2 torpedo boats[3] |

1879 (prewar) Chilean Army: 2,440[6] men Chilean Navy: 2 ironclads 9 wooden ships 4 torpedo boats[3] 1880 Chilean Army: 27,000 (Ante Lima) 8,000 (Occupation Force) 6,000 (Mainland)[7] Chilean Navy: 3 ironclads 8 wooden ships 10 torpedo boats[3] | ||||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||||

|

Killed and wounded: About 25,000[8] Captured: About 9,000[8] |

Killed: 2,791–2,825[9] Wounded: 7,193–7,347[9] | ||||||||

قالب:Campaignbox War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific (إسپانية: Guerra del Pacífico), also known as the Saltpeter War (إسپانية: Guerra del salitre) and by multiple other names was a war between Chile and a Bolivian–Peruvian alliance. It lasted from 1879 to 1884, and was fought over Chilean claims on coastal Bolivian territory in the Atacama Desert. The war ended with victory for Chile, which gained a significant amount of resource-rich territory from Peru and Bolivia. Chile's army took Bolivia's nitrate rich coastal region and Peru was defeated by Chile's navy.[10][11]

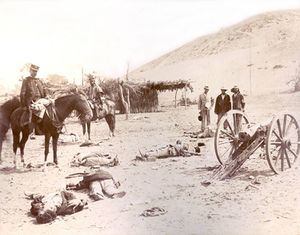

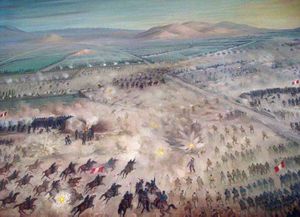

Battles were fought in the Pacific Ocean, the Atacama Desert, Peru's deserts, and mountainous regions in the Andes. For the first five months the war played out in a naval campaign, as Chile struggled to establish a sea-based resupply corridor for its forces in the world's driest desert.

In February 1878, Bolivia imposed a new tax on a Chilean mining company ("Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta", CSFA) despite Bolivian express warranty in the 1874 Boundary Treaty that it would not increase taxes on Chilean persons or industries for 25 years. Chile protested and solicited to submit it to mediation, but Bolivia refused and considered it a subject of Bolivia's courts. Chile insisted and informed the Bolivian government that Chile would no longer consider itself bound by the 1874 Boundary Treaty if Bolivia did not suspend enforcing the law. On February 14, 1879 when Bolivian authorities attempted to auction the confiscated property of CSFA, Chilean armed forces occupied the port city of Antofagasta.

Peru, bound to Bolivia by their secret treaty of alliance from 1873, tried to mediate, but on 1 March 1879 Bolivia declared war on Chile and called on Peru to activate their alliance, while Chile demanded that Peru declare its neutrality. On April 5, after Peru refused this, Chile declared war on both nations. The following day, Peru responded by acknowledging the casus foederis.

Ronald Bruce St. John in The Bolivia–Chile–Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert states:

Even though the 1873 treaty and the imposition of the 10 centavos tax proved to be the casus belli, there were deeper, more fundamental reasons for the outbreak of hostilities in 1879. On the one hand, there was the power, prestige, and relative stability of Chile compared to the economic deterioration and political discontinuity which characterised both Peru and Bolivia after independence. On the other, there was the ongoing competition for economic and political hegemony in the region, complicated by a deep antipathy between Peru and Chile. In this milieu, the vagueness of the boundaries between the three states, coupled with the discovery of valuable guano and nitrate deposits in the disputed territories, combined to produce a diplomatic conundrum of insurmountable proportions.[12]

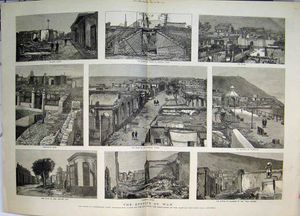

Afterwards, Chile's land campaign bested the Bolivian and Peruvian armies. Bolivia withdrew after the Battle of Tacna on May 26, 1880. Chilean forces occupied Lima in January 1881. Peruvian army remnants and irregulars waged a guerrilla war that did not change the war's outcome. Chile and Peru signed the Treaty of Ancón on October 20, 1883. Bolivia signed a truce with Chile in 1884.

Chile acquired the Peruvian territory of Tarapacá, the disputed Bolivian department of Litoral (turning Bolivia into a landlocked country), as well as temporary control over the Peruvian provinces of Tacna and Arica. In 1904, Chile and Bolivia signed the "Treaty of Peace and Friendship" establishing definite boundaries. The 1929 Tacna–Arica compromise gave Arica to Chile and Tacna to Peru.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Etymology

The conflict is also known as the "Saltpeter War", the "Ten Cents War" (in reference to the controversial ten-centavo tax imposed by the Bolivian government), and the "Second Pacific War".[13] It should not to be confused with the pre-Columbian Saltpeter War, in what is now Mexico, nor the "Guano War" as the Chincha Islands War is sometimes named.[14] The war largely settled (or set up, depending on one's point of view) the "Tacna-Arica dispute", and is sometimes known by that name as well, although the details took decades to resolve.

Wanu (Hispanicized guano) is a Quechua word for fertilizer.[15] Potassium nitrate (ordinary saltpeter) and sodium nitrate (Chile saltpeter) are nitrogen-containing compounds collectively referred to as salpeter, saltpetre, salitre, caliche, or nitrate. They are used as fertilizer, but have other important uses.

Atacama is a Chilean region south of the Atacama Desert, which mostly coincides with the disputed Antofagasta province, known in Bolivia as Litoral.

Background

The Atacama border dispute between Bolivia and Chile concerning the sovereignty over the coastal territories between approximately the parallels 23°S and 24°S was just one of several long-running border conflicts in South America as the area gained independence throughout the nineteenth century, since uncertainty characterized the demarcation of frontiers according to the Uti possidetis 1810, particularly in remote, thinly-populated portions of newly-independent nations.[16]

Boundary Treaty of 1866

Bolivia and Chile negotiated the "Boundary Treaty of 1866" ("Treaty of Mutual Benefits"). The treaty established the 24th parallel south, "from the littoral of the Pacific to the eastern limits of Chile", as their mutual boundary. The two countries also agreed to share the tax revenue from mineral exports from the territory between the 23rd and 25th parallel south. The bipartite tax collecting caused discontent, and the treaty lasted only 8 years.

Secret Alliance Treaty of 1873

Boundary Treaty of 1874

All disputes arising under the treaty would be settled by arbitration.

أسباب الحرب

American historian William F. Sater gives several possible and noncontradictory reasons for the beginning of the war.[17] He states that there are domestic, economic, and geopolitical reasons for going to war. Several authors agree with these reasons but others only partially support his arguments.

Some historians argue that Chile was devastated by the economic crisis of the 1870s[18] and was looking for a replacement for its silver, copper and wheat exports.[19] It has been argued that the economic situation and the view of new wealth in nitrate was the true reason for the Chilean elite to go to war against Peru and Bolivia.[19][20] The holder of the Chilean nitrate companies, says Sater, "bulldozed" Chilean president Aníbal Pinto into declaring war in order to protect the owner of the CSFA and later to seize Bolivia's and Peru's salitreras. (Several members of the Chilean government were stock holders of CSFA and it is believed that they hired the services of one of the country's newspapers to push their case).[17]

الأزمة

ضريبة العشر سنتات

- The license of 27 November 1873

- The Peruvian Monopoly of saltpeter

- The tax and the Chilean refusal

Invasion of Antofagasta

الوساطة الپيروڤية وإعلان بوليڤيا الحرب

الحرب

القوات في الحرب

| تشيلى | پيرو | بوليڤيا |

|---|---|---|

| يناير 1879، قبل الحرب | ||

| 2,440[n 1] | 5,557[n 2] | 1,687[n 3] |

| يناير 1881، قبل احتلال ليما | ||

| ante Lima: 27,000[n 4] | Army of Lima: 25–35,000[n 5] | في بوليڤيا: |

| Tarapacá & Antofagasta: 8,000[n 6] | In Arequipa: 13,000[n 7] | |

| في تشيلى: 6,000[n 8] | جيش الشمال: (أضيف إلى ليما) | |

| ||

| الموديل | الرقم | العيار مم |

الوزن كج |

المسافة م |

المقذوف كج |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| تشيلى | |||||

| مدفع كروپ جبلي M1873 L/21 | 12–16 | 60 | 107 | 2500 | 2.14 |

| مدفع كروپ ميداني M1867 L/25 | ? | 78.5 | ? | 3000 | 4.3 |

| مدفع كروپ جبلي M1879 L/13 | 38 | 75 | 100 | 3000 | 4.5 |

| مدفع كروپ جبلي M1879-80 L/24 | 24 | 87 | 305 | 4600 | 1.5 |

| مدفع كروپ ميداني M1880 L/27 | 29 | 75 | 100 | 4800 | 4.3 |

| مدفع كروپ ميداني M1873 L/24 | 12 | 88 | 450 | 4800 | 6.8 |

| Armstrong Bronze M1880 | 6 | 66 | 250 | 4500 | 4.1 |

| Model 59 Emperador | 12 | 87 | ? | 323 | 11.5 |

| La Hitte Field Gun M1858 | 4 | 84 | ? | 342 | 4.035 |

| La Hitte Mountain Gun M1858 | 8 | 86.5 | ? | 225 | 4035 |

| پيرو | |||||

| المدفع الأبيض (جبلي)[F 2] | 31 | 55 | ? | 2500 | 2.09 |

| المدفع الأبيض (ميداني) | 49 | 55 | ? | 3800 | 2.09 |

| Grieve Steel[F 3] | 42 | 60 | 107 | 2500 | 2.14 |

| بوليڤيا | |||||

| مدفع كروپ جبلي M1872 L/21 | 6 | 60 | 107 | 2500 | 2.14 |

| |||||

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الصراع للسيطرة على البحر

Given the few roads and railroad lines, the nearly waterless and largely unpopulated Atacama Desert was difficult to occupy. From the beginning naval superiority was critical.[21] Bolivia had no navy,[22] so on March 26, 1879 Hilarión Daza formally offered letters of marque to any ships willing to fight for Bolivia.[23] The Armada de Chile and Marina de Guerra del Perú fought the naval battles.

Early on, Chile blockaded the Peruvian port of Iquique on April 5.[24] In the Battle of Iquique (May 21, 1879), the Peruvian ironclad Huáscar engaged and sank the wooden Esmeralda; Meanwhile, in the Battle of Punta Gruesa, the Peruvian Independencia chased the schooner Covadonga until the heavier Independencia collided with a submerged rock and sank in the shallow waters near Punta Gruesa. In total, Peru stopped the blockade of Iquique, and Chileans lost the old Esmeralda. Nevertheless, the loss of the Independencia cost Peru 40% of its naval offensive power[25] and made a strong impression upon military leaders in Argentina, hence an Argentine intervention in the war became far more remote.[26]

Despite being outnumbered, the Peruvian monitor Huáscar held off the Chilean navy for six consecutive months and upheld Peruvian morale in the early stages of the conflict.[27]

The capture of the steamship Rímac on July 23, 1879 while carrying a cavalry regiment (the Carabineros de Yungay) was the Chilean army's largest loss to that point.[28] The loss led Admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo, chief of the Chilean Navy, on 17 August to resign. Commodore Galvarino Riveros Cárdenas replaced Williams, and he devised a plan to catch the Huáscar.[29]

Meanwhile, the Peruvian navy had some other actions, particularly in August 1879 during the (unsuccessful) raid of the Union to Punta Arenas, located at the Strait of Magellan in an attempt to capture the British ship Gleneg which transported weapons and supplies for Chile.[30]

| سفينة حربية | زنة (L.ton) |

حصان قدرة |

Speed (عقدة) |

التدريع (بوصة) |

المدفعية الرئيسية | بنيت السنة |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| تشيلى | ||||||

| Cochrane | 3,560 | 3,000 | 9–12.8 | up to 9 | 6x9 بوصة | 1874 |

| Blanco Encalada | 3,560 | 3,000 | 9–12.8 | up to 9 | 6x9 بوصة | 1874 |

| پيرو | ||||||

| هواسكار | 1,130 | 1,200 | 10–11 | 4½ | 2x300–pounders | 1865 |

| إندپندنسيا | 2,004 | 1,500 | 12–13 | 4½ | 2x150–pounders | 1865 |

الحرب البرية

After the battle of Angamos and once Chile achieved naval supremacy, the government had to decide where to strike. The options were Tarapacá, Moquegua or directly Lima. Because of the proximity to Chile and the capture of the Peruvian Salitreras, Chile decided to occupy first the Peruvian Province of Tarapacá.

حملة تاراپاكا

حملة تاكنا وأريكا

Meanwhile, Chile continued its advances in the Tacna and Arica Campaign. On November 28, ten days after the Battle of San Francisco, Chile declared the formal blockade of Arica. On December 31, a Chilean force of 600 men carried out an amphibious raid at Ilo as a reconnaissance in force, to the north of Tacna, withdrawing the same day.[34]

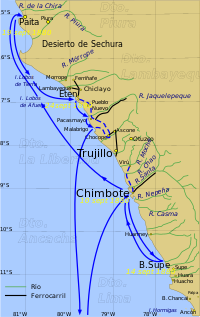

تجريدة لينش

To show Peru the futility of further resistance, on September 4, 1880 the Chilean government dispatched an expedition of 2,200 men[35] to northern Peru under the command of Captain Patricio Lynch to collect war taxes from wealthy landowners.خطأ استشهاد: إغلاق </ref> مفقود لوسم <ref> The Lackawanna Conference, also called the Arica conference, attempted to develop a peace settlement.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

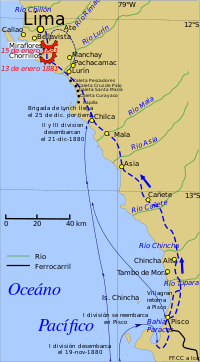

حملة ليما

- الإبرار في پيسكو وتشيلكا وكوراياكو ولورين

- Battle of Chorrillos and Miraflores

- نقد

Piérola's division of forces in two lines has been criticised by Chilean analyst Francisco Machuca.[36] Whether such criticism is justified is debatable. According to Gonzalo Bulnes the battles of Chorrillos and Miraflores have been amongst the biggest in South America regarding the number of combatants, 45,000 in Chorrillos and 25,000 in Miraflores. The estimated death toll was 11,000 to 14,000 personnel, with a further 10,144 injured.[37]

السياسات المحلية حتى سقوط ليما

الحرب في السييرا الپيروڤية

After the confrontations in Chorrillos and Miraflores, Peruvian dictator Piérola refused to negotiate with the Chileans and escaped to the central Andes to try governing from the rear, but soon he lost the representation of the Peruvian state.[38](He left Peru in December 1881).

تجريدة لتلييه

حملة سييرا 1882

حملة سييرا 1883

العواقب

The war had a profound and long lasting effect on the societies of the involved countries. The peace negotiations continued until 1929, but the war was over in 1884 for all practical purposes.[39]

التخليد

Día del Mar is celebrated in Bolivia on the 23 of March, at the conclusion of the weeklong Semana del Mar with a ceremony at La Paz's Plaza Abaroa, in homage to war hero Eduardo Abaroa, and in parallel ceremonies nationwide.

See also

|

General reference

Events leading Border dispute Economy

|

Peace treaties Aftermath

Cultural impact

|

Notes

References

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 51 Table 2

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 45 Table 1

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 74

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 274

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 58 Table 3

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsater2007_263 - ^ أ ب Sater 2007, p. 349 Table 23.

- ^ أ ب Sater 2007, p. 348 Table 22. The statistics on battlefield deaths are inaccurate because they do not provide follow up information on those who subsequently died of their wounds.

- ^ William F. Sater, "War of the Pacific" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 5, pp. 438-441. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1996.

- ^ Vincent Peloso, "History of Peru" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, p.367. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1996.

- ^ St. John, Ronald Bruce; Schofield, Clive (1994). The Bolivia–Chile–Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert. University of Durham, International Boundaries Research Unit. pp. 12–13. ISBN 1897643144.

- ^ Joao Resende-Santos (يوليو 23, 2007). Neorealism, States, and the Modern Mass Army. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46633-2.

- ^ The Guano War of 1865–1866, retrieved on 22 December 2014

- ^ قالب:Ref Laime0

- ^ Arie Marcelo Kacowicz (1998). Zones of Peace in the Third World: South America and West Africa in Comparative Perspective. SUNY Press. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-0-7914-3957-9.

- ^ أ ب Sater 2007, p. 37

- ^ Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores. 2002. Gabriel Salazar and Julio Pinto. p. 25-29.

- ^ أ ب Salazar & Pinto 2002, pp. 25–29.

- ^ Pinto Rodríguez, Jorge (1992), "Crisis económica y expansión territorial : la ocupación de la Araucanía en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX", Estudios Sociales 72

- ^ Farcau 2000, p. 65

- As the earlier discussion of the geography of the Atacama region illustrates, control of the sea lanes along the coast would be absolutely vital to the success of a land campaign there

- ^ Farcau 2000, p. 57

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 102 and ff

- "... to anyone willing to sail under Bolivia's colors ..."

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 119

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 137

- ^ Robert N. Burr (1967). By Reason Or Force: Chile and the Balancing of Power in South America, 1830–1905. University of California Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-520-02629-2.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةClayton1985 - ^ Farcau 2000, p. 214

- ^ Sater 2007, pp. 151–152

- ^ Sater 2007

- ^ Sater 2007, pp. 113–114

- "There are numerous differences of opinion as to the ships' speed and armament. Some of these differences can be attributed to the fact that the various sources may have been evaluating the ships at different times."

- ^ Diario El Mercurio, del Domingo 28 de abril de 2002 en archive.org

- ^ Méndez Notari, Carlos (2009). Héroes del Silencio, Veteranos De La Guerra del Pacífico (1884–1924). Santiago: Centro de Estudios Bicentenario. ISBN 978-956-8147-77-8.

- ^ Farcau 2000, p. 130

- ^ Farcau 2000, p. 152

- "Lynch's force consisted of the 1° Line Regiment and the Regiments "Talca" and "Colchagua", a battery of mountain howitzers, and a small cavalry squadron for a total of twenty-two hundred man"

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFM - ^ Sater 2007, pp. 348–349

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 302

- ^ Farcau 2000, p. 191

- ^ filmaffinity web site, retrieved on 15 April 2015

- ^ Páginas Heróicas

Further reading

- Barros Arana, Diego (1881a). Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879–1880) (History of the War of the Pacific (1879–1880)) (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Santiago, Chile: Librería Central de Servat i Ca.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Barros Arana, Diego (1881b). Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879–1880) (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Santiago, Chile: Librería Central de Servat i Ca.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Basadre, Jorge (1964). Historia de la Republica del Peru, La guerra con Chile (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Peruamerica S.A. Archived from the original on ديسمبر 11, 2007.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Boyd. Robert N. Chili: Sketches of Chili and the Chilians During the War 1879-1880. (1881)

- Bulnes, Gonzalo (1920). Chile and Peru: the causes of the war of 1879. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Universitaria.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Villalobos, Sergio (2004). Chile y Perú, la historia que nos une y nos separa, 1535–1883 (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Chile: Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 9789561116016.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - English, Adrian J. (1985). Armed forces of Latin America: their histories, development, present strength, and military potential. Jane's Information Group, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-7106-0321-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farcau, Bruce W. (2000). The Ten Cents War, Chile, Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. Westport, Connecticut, London: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-96925-7. Retrieved يناير 17, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jefferson Dennis, William (1927). "Documentary history of the Tacna-Arica dispute from University of Iowa studies in the social sciences". 8. Iowa: University Iowa City.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Paz Soldan, Mariano Felipe (1884). Narracion Historica de la Guerra de Chile contra Peru y Bolivia (Historical narration of the Chile's War against Peru and Bolivia) (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Imprenta y Libreria de Mayo, calle Peru 115.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Sater, William F. (2007). Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sater, William F. (1986). Chile and the War of the Pacific. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4155-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791–1899. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-57488-450-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - O'Brien, Thomas F. (1980). "The Antofagasta Company: A Case Study of Peripheral Capitalism". Duke University Press: Hispanic American Historical Review.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Querejazu Calvo, Roberto (1979). Guano, Salitre y Sangre (in Spanish). La Paz-Cochabamba, Bolivia: Editorial los amigos del Libro.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Querejazu Calvo, Roberto (1995). Aclaraciones históricas sobre la Guerra del Pacífico (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia: Editorial los amigos del Libro.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Kiernan, Victor (1955). "Foreign Interests in the War of the Pacific". XXXV (pages 14–36 ed.). Duke University Press: Hispanic American Historical Review.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Yrigoyen, Pedro (1921). "La alianza perú-boliviano-argentina y la declaratoria de guerra de Chile" (in Spanish). Lima: San Marti & Cía. Impresores.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

External links

- Chilean caricatures during the war in Tesis of Patricio Ibarra Cifuentes, Universidad de Chile, 2009.

- Article Caliche: the conflict mineral that fuelled the first world war in The Guardian by Daniel A. Gross, 2 June 2014.

- Use mdy dates from September 2012

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using multiple image with manual scaled images

- History of South America

- Wars involving Bolivia

- Wars involving Chile

- Wars involving Peru

- War of the Pacific

- 19th century in Bolivia

- 19th century in Chile

- Territorial disputes of Chile

- Territorial disputes of Bolivia

- Territorial disputes of Peru

- Bolivia–Chile relations

- Chile–Peru relations

- Bolivia–Peru relations

- Conflicts in 1879

- Conflicts in 1880

- Conflicts in 1881

- Conflicts in 1882

- Conflicts in 1883