غابة مدارية مطيرة

الغابات المدارية المطيرة Tropical rainforests، هي غابات مطيرة متشابكة توجد بين خطي العرض 10 شمال و 10 جنوب خط الاستواء. They are a subset of the tropical forest biome that occurs roughly within the 28° latitudes (in the torrid zone between the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn). Tropical rainforests are a type of tropical moist broadleaf forest, that includes the more extensive seasonal tropical forests.[3] True rainforests usually occur in tropical rainforest climates where no dry season occurs; all months have an average precipitation of at least 60 mm (2.4 in). Seasonal tropical forests with tropical monsoon or savanna climates are sometimes included in the broader definition.

Tropical rainforests ecosystems are distinguished by their consistent, high temperatures, exceeding 18 °C (64 °F) monthly, and substantial annual rainfall. The abundant rainfall results in nutrient-poor, leached soils, which profoundly affect the flora and fauna adapted to these conditions. These rainforests are renowned for their significant biodiversity. They are home to 40–75% of all species globally, including half of the world's animal and plant species, and two-thirds of all flowering plant species. Their dense insect population and variety of trees and higher plants are notable. Described as the "world's largest pharmacy", over a quarter of natural medicines have been discovered in them. However, tropical rainforests are threatened by human activities, such as logging and agricultural expansion, leading to habitat fragmentation and loss.

The structure of a tropical rainforest is stratified into layers, each hosting unique ecosystems. These include the emergent layer with towering trees, the densely populated canopy layer, the understory layer rich in wildlife, and the forest floor, which is sparse due to low light penetration. The soil is characteristically nutrient-poor and acidic. Tropical rainforests have a long history of ecological succession, influenced by natural events and human activities. They are crucial for global ecological functions, including carbon sequestration and climate regulation. Many indigenous peoples around the world have inhabited rainforests for millennia, relying on them for sustenance and shelter, but face challenges from modern economic activities.

Conservation efforts are diverse, focusing on both preservation and sustainable management. International policies, such as the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD and REDD+) programs, aim to curb deforestation and forest degradation. Despite these efforts, tropical rainforests continue to face significant threats from deforestation and climate change, highlighting the ongoing challenge of balancing conservation with human development needs.

نظرة عامة

Tropical rainforests are hot and wet. Mean monthly temperatures exceed 18 °C (64 °F) during all months of the year.[4] Average annual rainfall is no less than 1،680 mm (66 in) and can exceed 10 m (390 in) although it typically lies between 1،750 mm (69 in) and 3،000 mm (120 in).[5] This high level of precipitation often results in poor soils due to leaching of soluble nutrients in the ground.

Tropical rainforests exhibit high levels of biodiversity. Around 40% to 75% of all biotic species are indigenous to the rainforests.[6] Rainforests are home to half of all the living animal and plant species on the planet.[7] Two-thirds of all flowering plants can be found in rainforests. A single hectare of rainforest may contain 42,000 different species of insect, up to 807 trees of 313 species and 1,500 species of higher plants.[5] Tropical rainforests have been called the "world's largest pharmacy", because over one quarter of natural medicines have been discovered within them.[8][9] It is likely that there may be many millions of species of plants, insects and microorganisms still undiscovered in tropical rainforests.

Tropical rainforests are among the most threatened ecosystems globally due to large-scale fragmentation as a result of human activity. Habitat fragmentation caused by geological processes such as volcanism and climate change occurred in the past, and have been identified as important drivers of speciation.[10] However, fast human driven habitat destruction is suspected to be one of the major causes of species extinction. Tropical rain forests have been subjected to heavy logging and agricultural clearance throughout the 20th century, and the area covered by rainforests around the world is rapidly shrinking.[11][12]

تاريخ

Tropical rainforests have existed on earth for hundreds of millions of years. Most tropical rainforests today are on fragments of the Mesozoic era supercontinent of Gondwana. The breakup of Gondwana left tropical rainforests located in five major regions of the world: tropical America, Africa, Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and New Guinea, with smaller outliers in Australia.[13] However, the specifics of the origin of rainforests remain uncertain due to an incomplete fossil record.

أنواع أخرى من الغابات المدارية

Several biomes may appear similar to, or merge via ecotones with, tropical rainforest:

- Moist seasonal tropical forest

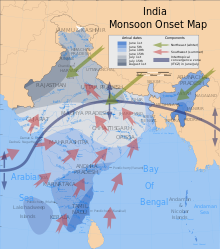

Moist seasonal tropical forests receive high overall rainfall with a warm summer wet season and a cooler winter dry season. These forests usually fall under tropical monsoon or tropical savanna climates. Some trees in these forests drop some or all of their leaves during the winter dry season, thus they are sometimes called "tropical mixed forest". They are found in parts of South America, in Central America and around the Caribbean, in coastal West Africa, parts of the Indian subcontinent, and across much of Indochina.

- Montane rainforests

These are found in cooler-climate mountainous areas, becoming known as cloud forests at higher elevations. Depending on latitude, the lower limit of montane rainforests on large mountains is generally between 1500 and 2500 m while the upper limit is usually from 2400 to 3300 m.[14]

- Flooded rainforests

Tropical freshwater swamp forests, or "flooded forests", are found in Amazon basin (the Várzea) and elsewhere.

بنية الغابة

Rainforests are divided into different strata, or layers, with vegetation organized into a vertical pattern from the top of the soil to the canopy.[15] Each layer is a unique biotic community containing different plants and animals adapted for life in that particular strata. Only the emergent layer is unique to tropical rainforests, while the others are also found in temperate rainforests.[16]

أرض الغابة

The forest floor, the bottom-most layer, receives only 2% of the sunlight. Only plants adapted to low light can grow in this region. Away from riverbanks, swamps and clearings, where dense undergrowth is found, the forest floor is relatively clear of vegetation because of the low sunlight penetration. This more open quality permits the easy movement of larger animals such as: ungulates like the okapi (Okapia johnstoni), tapir (Tapirus sp.), Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), and apes like the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), as well as many species of reptiles, amphibians, and insects. The forest floor also contains decaying plant and animal matter, which disappears quickly, because the warm, humid conditions promote rapid decay. Many forms of fungi growing here help decay the animal and plant waste.

Understory layer

The understory layer lies between the canopy and the forest floor. The understory is home to a number of birds, small mammals, insects, reptiles, and predators. Examples include leopard (Panthera pardus), poison dart frogs (Dendrobates sp.), ring-tailed coati (Nasua nasua), boa constrictor (Boa constrictor), and many species of Coleoptera.[5] The vegetation at this layer generally consists of shade-tolerant shrubs, herbs, small trees, and large woody vines which climb into the trees to capture sunlight. Only about 5% of sunlight breaches the canopy to arrive at the understory causing true understory plants to seldom grow to 3 m (10 feet). As an adaptation to these low light levels, understory plants have often evolved much larger leaves. Many seedlings that will grow to the canopy level are in the understory.

طبقة الظلة

The canopy is the primary layer of the forest, forming a roof over the two remaining layers. It contains the majority of the largest trees, typically 30–45 m in height. Tall, broad-leaved evergreen trees are the dominant plants. The densest areas of biodiversity are found in the forest canopy, as it often supports a rich flora of epiphytes, including orchids, bromeliads, mosses and lichens. These epiphytic plants attach to trunks and branches and obtain water and minerals from rain and debris that collects on the supporting plants. The fauna is similar to that found in the emergent layer, but more diverse. It is suggested that the total arthropod species richness of the tropical canopy might be as high as 20 million.[17] Other species inhabiting this layer include many avian species such as the yellow-casqued wattled hornbill (Ceratogymna elata), collared sunbird (Anthreptes collaris), grey parrot (Psitacus erithacus), keel-billed toucan (Ramphastos sulfuratus), scarlet macaw (Ara macao) as well as other animals like the spider monkey (Ateles sp.), African giant swallowtail (Papilio antimachus), three-toed sloth (Bradypus tridactylus), kinkajou (Potos flavus), and tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla).[5]

طبقة ناشئة

The emergent layer contains a small number of very large trees, called emergents, which grow above the general canopy, reaching heights of 45–55 m, although on occasion a few species will grow to 70–80 m tall.[15][18] Some examples of emergents include: Hydrochorea elegans, Dipteryx panamensis, Hieronyma alchorneoides, Hymenolobium mesoamericanum, Lecythis ampla and Terminalia oblonga.[19] These trees need to be able to withstand the hot temperatures and strong winds that occur above the canopy in some areas. Several unique faunal species inhabit this layer such as the crowned eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus), the king colobus (Colobus polykomos), and the large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus).[5]

However, stratification is not always clear. Rainforests are dynamic and many changes affect the structure of the forest. Emergent or canopy trees collapse, for example, causing gaps to form. Openings in the forest canopy are widely recognized as important for the establishment and growth of rainforest trees. It is estimated that perhaps 75% of the tree species at La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica are dependent on canopy opening for seed germination or for growth beyond sapling size, for example.[20]

البيئة

المناخ

التربة

أنواع التربة

إعادة تدوير المواد الغذائية

دعم جذور

تعاقب الغابة

الجغرافيا

أمريكا الجنوبية والوسطى

أفريقيا

آسيا

استراليا واوقيانوسيا

التنوع الحيوي والانتواع

المنافسة بين الأنواع الافتراضية

Pleistocene refugia

الأبعاد البشرية

الإسكان

الشعوب الأصلية

الموارد

الأطعمة والتوابل المزروعة

خدمات النظام البيئي

السياحة

الحفظ

الأخطار

التعدين والتنقيب

التحويل إلى أراضي زراعية

تغير المناخ

الحماية

مصادر أكاديمية

- Agricultural and Forest Meteorology[21]

- Annals of Botany[22]

- Austral Ecology

- Biodiversity and Conservation, ISSN: 0960-3115 eISSN: 1572-9710[23]

- Biological Conservation[24]

- Diversity and Distributions[25]

- Ecological Indicators[26]

- Ecological Management & Restoration[27]

- Ecoscience[28]

- Journal of Tropical Ecology[29]

- Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology[30]

- Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment[31]

قراءات للإستزادة

- List of tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests ecoregions

- Palaeogeography

- Rainforest

- Temperate rain forest

- Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests

- Tropical rainforest climate

- Tropical Africa

المصادر

- ^ NASA.gov

- ^ ScienceDaily.com

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةOlson - ^ Woodward, Susan. Tropical broadleaf Evergreen Forest: The rainforest. Archived 25 فبراير 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 14 March 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Newman, Arnold (2002). Tropical Rainforest: Our Most Valuable and Endangered Habitat With a Blueprint for Its Survival into the Third Millennium (2 ed.). Checkmark. ISBN 0-8160-3973-9.

- ^ "Rainforests.net – Variables and Math". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ The Regents of the University of Michigan. The Tropical Rain Forest. Retrieved on 14 March 2008.

- ^ Rainforests Archived 8 يوليو 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Animalcorner.co.uk (1 January 2004). Retrieved on 28 March 2013.

- ^ The bite that heals. Ngm.nationalgeographic.com (25 February 2013). Retrieved on 24 June 2016.

- ^ Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. & Falcon-Lang, H.J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica". Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. Bibcode:2010Geo....38.1079S. doi:10.1130/G31182.1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brazil: Deforestation rises sharply as farmers push into Amazon, The Guardian, 1 September 2008

- ^ China is black hole of Asia's deforestation, Asia News, 24 March 2008

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCorlettandPrimack2006 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBruijnzeel - ^ أ ب Bourgeron, Patrick S. (1983). "Spatial Aspects of Vegetation Structure". In Frank B. Golley (ed.). Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystems. Structure and Function. Ecosystems of the World (14A ed.). Elsevier Scientific. pp. 29–47. ISBN 0-444-41986-1.

- ^ Webb, Len (1 October 1959). "A Physiognomic Classification of Australian Rain Forests". Journal of Ecology. British Ecological Society : Journal of Ecology Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 551–570. 47 (3): 551–570. Bibcode:1959JEcol..47..551W. doi:10.2307/2257290. JSTOR 2257290.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةErwin - ^ "Sabah". Eastern Native Tree Society. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKing - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDenslow - ^ Elsevier. "Agricultural and Forest Meteorology". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Oxford University Press. "Annals of botany". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Springer. "Biodiversity and Conservation". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Elsevier. "Biological Conservation". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Diversity and Distributions". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Elsevier. "Ecological Indicators". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ John Wiley & Sons. "Ecological Management & Restoration". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ BioOne. "Ecoscience". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cambridge University Press. "Journal of Tropical Ecology". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Elsevier. "Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Taylor & Francis. "Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment". Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

وصلات خارجية

- Rainforest Action Network

- EIA forest reports: Investigations into illegal logging.

- EIA in the USA Reports and info.

- Rain Forest Info from Blue Planet Biomes

- Passport to Knowledge Rainforests

- Rainforest protection

- Amazon - What you can do

- Protect Ancient Fores