جنوب التيرول

جنوب التيرول

South Tyrol Autonome Provinz Bozen — Südtirol Provincia autonoma di Bolzano — Alto Adige Provinzia autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan — Südtirol | |

|---|---|

خريطة توضح موقع مقاطعة جنوب التيرول في إيطاليا (بالأحمر) | |

| الإحداثيات: 46°30′N 11°20′E / 46.5°N 11.33°E | |

| البلد | |

| المنطقة | ترنتينو-ألتو أديگه/سودتيرو |

| العاصمة | بولسانو |

| كميوني | 116 |

| الحكومة | |

| • الكيان | Provincial Council |

| • الحاكم | أرنو كومپاتشر (SVP) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 7٬399٫97 كم² (2٬857٫14 ميل²) |

| التعداد (31 December 2024) | |

| • الإجمالي | 539٬386 |

| • الكثافة | 73/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €32 billion (2023) |

| • Per capita | €62,100 (2023) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 39XXX |

| Telephone prefix | 0471, 0472, 0473, 0474 |

| لوحة السيارة | BZ |

| HDI (2022) | 0.925[2] very high 5th of 21 |

| ISTAT | 021 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

جنوب التيرول[أ] (ألمانية: Südtirol [ˈzyːtːiˌʁoːl] استمع , محلياً [ˈsyːtiˌroːl]؛ إيطالية: Alto Adige [ˈalto ˈaːdidʒe]؛ Ladin: Südtirol)، رسمياً المقاطعة الذاتية بولزانو/بوزن – جنوب التيرول،[4][ب] هي مقاطعة ذاتية الحكم في شمال إيطاليا.[5] وهي واحدة من مقاطعتين تتمتعان بالحكم الذاتي وتشكلات منطقة ترنتينو-ألتو أديگه-سودتيرول. تبلغ مساحة المقاطعة 7،400 متر كيلومربع (2،857 sq mi) ويصل إجمالي تعداد سكانها 534,000 نسمة (في 2021).[6] عاصمتها مدينة بولزانو (بالألمانية: Bozen؛ باللادينية: Balsan or Bulsan).

South Tyrol has a considerable level of self-government, consisting of a large range of exclusive legislative and executive powers and a fiscal regime that allows it to retain 90% of revenue, while remaining a net contributor to the national budget. As of 2023, it is Italy's wealthiest province and among the wealthiest in the European Union. As of 2024, South Tyrol was also the region with the lowest number of persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU, with 6.6% of the population compared to the EU mean of 21.4%.[7]

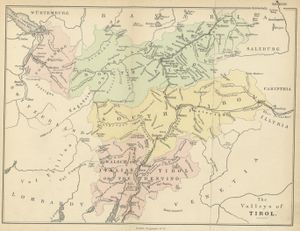

In the wider context of the EU, the province is one of the three members of the Tyrol–South Tyrol–Trentino Euroregion, which corresponds almost exactly to the historical region of Tyrol.[8]

حسب بيانات 2014 المعتمدة على تعداد 2024، 57.6 بالمائة من السكان يستخدمون الألمانية (ألمانية قياسية) بالصيغة المكتوبة واللهجة النمساوية-الباڤارية (بالصيغة المنطوقة)؛ 23.4 بالمائة من السكان يستخدمون الإيطالية، خاصة في المناطق المحيطة لأكبر مدينتين (بولزانو ومرانو)؛ 4.1 بالمائة يستخدمون اللادينية، اللغة الرايتو-رومانسية؛ 16.1% من السكان (خاصة المهاجرون الجدد) يستخدمون لغات أخرى كلغة أولى. Of 116 South Tyrolean municipalities, 102 have a German-speaking, eight a Ladin-speaking, and six an Italian-speaking majority.[9] The Italianization of South Tyrol and the settlement of Italians from the rest of Italy after 1918 significantly modified local demographics.[10][11]

التسمية

South Tyrol (occasionally South Tirol) is the term most commonly used in English for the province,[12] and its usage reflects that it was created from a portion of the southern part of the historic County of Tyrol, a former state of the Holy Roman Empire and crown land of the Austrian Empire of the Habsburgs. German and Ladin speakers usually refer to the area as Südtirol; the Italian equivalent Sudtirolo (sometimes parsed Sud Tirolo[13]) is becoming increasingly common.[14]

Alto Adige (literally translated in English: "Upper Adige"), one of the Italian names for the province, is also used in English.[15] The term had been the name of political subdivisions along the Adige River in the time of Napoleon Bonaparte,[16][17] who created the Department of Alto Adige, part of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. It was reused as the Italian name of the current province after its post-World War I creation, and was a symbol of the subsequent forced Italianization of South Tyrol.[18]

The official name of the province today in German is Autonome Provinz Bozen — Südtirol. German speakers usually refer to it not as a Provinz, but as a Land (like the Länder of Germany and Austria).[19] Provincial institutions are referred to using the prefix Landes-, such as Landesregierung (state government) and Landeshauptmann (governor).[20] The official name in Italian is Provincia autonoma di Bolzano — Alto Adige, in Ladin Provinzia autonoma Bulsan — Südtirol.[21][22]

التاريخ

ضمها من قبل إيطاليا

South Tyrol as an administrative entity originated during the First World War. The Allies promised the area to Italy in the Treaty of London of 1915 as an incentive to enter the war on their side. Until 1918, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian princely County of Tyrol, but this almost completely German-speaking territory was occupied by Italy at the end of the war in November 1918 and was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy in 1919. The province as it exists today was created in 1926 after an administrative reorganization of the Kingdom of Italy, and was incorporated together with the province of Trento into the newly created region of Venezia Tridentina ("Trentine Venetia").

With the rise of Italian Fascism, the new regime made efforts to bring forward the Italianization of South Tyrol. The German language was banished from public service, German teaching was officially forbidden, and German newspapers were censored (with the exception of the fascistic Alpenzeitung). The regime also favoured immigration from other Italian regions.

The subsequent alliance between Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini declared that South Tyrol would not follow the destiny of Austria, which had been annexed by Nazi Germany. Instead the dictators agreed that the German-speaking population be transferred to German-ruled territory or dispersed around Italy, but the outbreak of the Second World War prevented them from fully carrying out their plans.[23] Every citizen was given the choice to give up their German cultural identity and stay in fascist Italy, or to leave their homeland for Nazi Germany to retain their cultural identity. This resulted in the division of South Tyrolese families.

In this tense relationship for the population, Walter Caldonazzi from Mals was part of the resistance group around the priest Heinrich Maier, which passed plans and information about production facilities for V-1 rockets, V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks, Messerschmitt Bf 109, and Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet and other aircraft to the Allies. The group planned for an independent Austria with a monarchical form of government after the war, which would include Austria, Bavaria and South Tyrol.[24][25]

In 1943, when the Italian government signed an armistice with the Allies, the region was occupied by Nazi Germany, which reorganised it as the Operation Zone of the Alpine Foothills and put it under the administration of Gauleiter Franz Hofer. The region was de facto annexed to the German Reich (with the addition of the province of Belluno) until the end of the war. Italian rule was restored in 1945 as the Nazi regime ended.

اتفاقية گروبر-دى گاسپري

After the war, the Allies decided that the province would remain a part of Italy, under the condition that the German-speaking population be granted a significant level of self-government. Italy and Austria negotiated an agreement in 1946, recognizing the rights of the German minority. Alcide De Gasperi, Italy's prime minister, a native of Trentino, wanted to extend the autonomy to his fellow citizens. This led to the creation of the region called Trentino-Alto Adige/Tiroler Etschland. The Gruber–De Gasperi Agreement of September 1946 was signed by the Italian and Austrian Foreign Ministers, creating the autonomous region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, consisting of the autonomous provinces of Trentino and South Tyrol. German and Italian were both made official languages, and German-language education was permitted once more. Still Italians were the majority in the combined region.

This, together with the arrival of new Italian-speaking immigrants, led to strong dissatisfaction among South Tyrolese, which culminated in terrorist acts perpetrated by the Befreiungsausschuss Südtirol (BAS – Liberation Committee of South Tyrol). In the first phase, only public edifices and fascist monuments were targeted. The second phase was bloodier, costing 21 lives (15 members of Italian security forces, two civilians, and four terrorists).

زودتيرولفراگه

The South Tyrolean Question (Südtirolfrage) became an international issue. As the implementation of the post-war agreement was deemed unsatisfactory by the Austrian government, it became a cause of significant friction with Italy and was taken up by the United Nations in 1960. A fresh round of negotiations took place in 1961 but proved unsuccessful, partly because of the campaign of terrorism.

The issue was resolved in 1971, when a new Austro-Italian treaty was signed and ratified. It stipulated that disputes in South Tyrol would be submitted for settlement to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, that the province would receive greater autonomy within Italy, and that Austria would not interfere in South Tyrol's internal affairs. The new agreement proved broadly satisfactory to the parties involved, and the separatist tensions soon eased.

The autonomous status granted in 1972 has resulted in a considerable level of self-government,[26] and also allows the entity to retain almost 90% of all levied taxes.[27]

الحكم الذاتي

In 1992, Italy and Austria officially ended their dispute over the autonomy issue on the basis of the agreement of 1972.[28]

The extensive self-government[26] provided by the current institutional framework has been advanced as a model for settling interethnic disputes and for the successful protection of linguistic minorities.[29] This is among the reasons why the Ladin municipalities of Cortina d'Ampezzo/Anpezo, Livinallongo del Col di Lana/Fodom and Colle Santa Lucia/Col have asked in a referendum to be detached from Veneto and reannexed to the province, from which they were separated under the fascist government.[30]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, South Tyrol maintained regular cross-border activities. It passed a law to reopen early from lockdown, and supplied face masks (via Austria) to the rest of Italy during a national shortage.[31]

المنطقة الأوروپية

In 1996, the Euroregion Tyrol-South Tyrol-Trentino was formed. As well as South Tyrol, the other members are the Austrian federal state Tyrol to the north and east and the Italian autonomous province of Trento to the south. The boundaries of the association correspond to the old County of Tyrol. The aim is to promote regional peace, understanding and cooperation in many areas. The region's assemblies meet together as one on various occasions, and have set up a common liaison office with the European Union in Brussels.

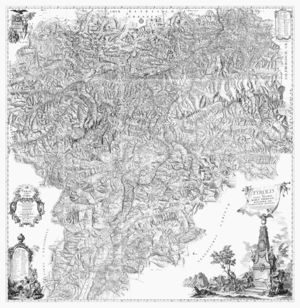

الجغرافيا

South Tyrol is located at the northernmost point in Italy. The province is bordered by Austria to the east and north, specifically by the Austrian states Tyrol and Salzburg, and by the Swiss canton of Graubünden to the west. The Italian provinces of Belluno, Trentino, and Sondrio border to the southeast, south, and southwest, respectively.

The landscape itself is mostly cultivated with different types of shrubs and forests and is highly mountainous.

Entirely located in the Alps, the province's landscape is dominated by mountains. The highest peak is the Ortler (3،905 متر، 12،812 ft) in the far west, which is also the highest peak in the Eastern Alps outside the Bernina Range. Even more famous are the craggy peaks of the Dolomites in the eastern part of the region.

The following mountain groups are (partially) in South Tyrol. All but the Sarntal Alps are on the border with Austria, Switzerland, or other Italian provinces. The ranges are clockwise from the west and for each the highest peak is given that is within the province or on its border.

| الاسم | أعلى نقطة (بالألمانية/بالإيطالية) | بالمتر | بالقدم |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ortler Alps | Ortler/Ortles | 3,905 | 12,811 |

| Sesvenna Range | Muntpitschen/Monpiccio | 3,162 | 10,374 |

| Ötztal Alps | Weißkugel/Palla Bianca | 3,746 | 12,291 |

| Stubai Alps | Wilder Freiger/Cima Libera | 3,426 | 11,241 |

| Sarntal Alps | Hirzer/Punta Cervina | 2,781 | 9,124 |

| Zillertal Alps | Hochfeiler/Gran Pilastro | 3,510 | 11,515 |

| Hohe Tauern | Dreiherrnspitze/Picco dei Tre Signori | 3,499 | 11,480 |

| Eastern Dolomites | Dreischusterspitze/Punta Tre Scarperi | 3,152 | 10,341 |

| Western Dolomites | Langkofel/Sassolungo | 3,181 | 10,436 |

Located between the mountains are many valleys, where the majority of the population lives.

التقسيمات الإدارية

The province is divided into eight districts (German: Bezirksgemeinschaften, Italian: comunità comprensoriali), one of them being the chief city of Bolzano. Each district is headed by a president and two bodies called the district committee and the district council. The districts are responsible for resolving intermunicipal disputes and providing roads, schools, and social services such as retirement homes.

The province is further divided into 116 Gemeinden or comuni.[32]

الأقسام

| القسم (بالألمانية/بالإيطالية) | العاصمة (بالألمانية/بالإيطالية) | المساحة | السكان[32] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bozen/Bolzano | Bozen/Bolzano | 52 كم² | 103,135 |

| Burggrafenamt/Burgraviato | Meran/Merano | 1,101 كم² | 97,315 |

| Pustertal/Val Pusteria | Bruneck/Brunico | 2,071 كم² | 79,086 |

| Überetsch-Unterland/Oltradige-Bassa Atesina | Neumarkt/Egna | 424 كم² | 71,435 |

| Eisacktal/Valle Isarco | Brixen/Bressanone | 624 كم² | 49,840 |

| Salten-Schlern/Salto-Sciliar | Bozen/Bolzano | 1,037 كم² | 48,020 |

| Vinschgau/Val Venosta | Schlanders/Silandro | 1,442 كم² | 35,000 |

| Wipptal/Alta Valle Isarco | Sterzing/Vipiteno | 650 كمك² | 18,220 |

أكبر البلديات

| الاسم الألماني | الاسم الإيطالي | الاسم اللاتيني | السكان[32] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bozen | Bolzano | Balsan, Bulsan | 103,189 |

| Meran | Merano | Maran | 38,836 |

| Brixen | Bressanone | Persenon, Porsenù | 21,189 |

| Leifers | Laives | 17,555 | |

| Bruneck | Brunico | Bornech, Burnech | 15,823 |

| Eppan an der Weinstraße | Appiano sulla Strada del Vino | 14,013 | |

| Lana | Lana | 11,120 | |

| Kaltern an der Weinstraße | Caldaro sulla Strada del Vino | 7,512 | |

| Ritten | Renon | 7,507 | |

| Sarntal | Sarentino | 6,863 | |

| Kastelruth | Castelrotto | Ciastel | 6,456 |

| Sterzing | Vipiteno | 6,306 | |

| Schlanders | Silandro | 6,014 | |

| Ahrntal | Valle Aurina | 5,876 | |

| Naturns | Naturno | 5,440 | |

| Sand in Taufers | Campo Tures | 5,230 | |

| Latsch | Laces | 5,145 | |

| Klausen | Chiusa | Tluses, Tlüses | 5,134 |

| Mals | Malles | 5,050 | |

| Neumarkt | Egna | 4,926 | |

| Algund | Lagundo | 4,782 | |

| St.Ulrich | Ortisei | Urtijëi | 4,606 |

| Ratschings | Racines | 4,331 | |

| Terlan | Terlano | 4,132 |

المناخ

Climatically, South Tyrol may be divided into five distinct groups:

The Adige valley area, with cold winters (24-hour averages in January of about 0 °C (32 °F)) and warm summers (24-hour averages in July of about 23 °C (73 °F)), usually classified as humid subtropical climate — Cfa. It has the driest and sunniest climate of the province. The main city in this area is Bolzano.

The midlands, between 300 و 900 متر (980 و 2،950 ft), with cold winters (24-hour averages in January between −3 و 1 °C (27 و 34 °F)) and mild summers (24-hour averages in July between 15 و 21 °C (59 و 70 °F)). This is a typical oceanic climate, classified as Cfb. It is usually wetter than the subtropical climate, and very snowy during the winters. During the spring and autumn, there is an extended foggy season, but fog may occur even on summer mornings. Main towns in this area are Meran, Bruneck, Sterzing, and Brixen. Near the lakes in higher lands (between 1،000 و 1،400 متر (3،300 و 4،600 ft)) the humidity may make the climate in these regions milder during winter, but also cooler in summer, making it more similar to a subpolar oceanic climate, Cfc.

The alpine valleys between 900 و 1،400 متر (3،000 و 4،600 ft), with a typically humid continental climate — Dfb, covering the largest part of the province. The winters are usually very cold (24-hour averages in January between −8 و −3 °C (18 و 27 °F)), and the summers, mild with averages between 14 و 19 °C (57 و 66 °F). It is a very snowy climate; snow may occur from early October to April or even May. Main municipalities in this area are Urtijëi, Badia, Sexten, Toblach, Stilfs, Vöran, and Mühlwald.

The alpine valleys between 1،400 و 1،700 متر (4،600 و 5،600 ft), with a subarctic climate — Dfc, with harsh winters (24-hour averages in January between −9 و −5 °C (16 و 23 °F)) and cool, short, rainy and foggy summers (24-hour averages in July of about 12 °C (54 °F)). These areas usually have five months below the freezing point, and snow sometimes occurs even during the summer, in September. This climate is the wettest of the province, with large rainfalls during the summer, heavy snowfalls during spring and fall. The winter is usually a little drier, marked by freezing and dry weeks, although not sufficiently dry to be classified as a Dwc climate. Main municipalities in this area are Corvara, Sëlva, Santa Cristina Gherdëina.

The highlands above 1،700 متر (5،600 ft), with an alpine tundra climate, ET, which becomes an ice cap climate, EF, above 3،000 متر (9،800 ft). The winters are cold, but sometimes not as cold as the higher valleys' winters. In January, most of the areas at 2،000 متر (6،600 ft) have an average temperature of about −5 °C (23 °F), while in the valleys at about 1،600 متر (5،200 ft), the mean temperature may be as low as −8 أو −9 °C (18 أو 16 °F). The higher lands, above 3،000 متر (9،800 ft) are usually extremely cold, with averages of about −14 °C (7 °F) during the coldest month, January.

Geology

The periadriatic seam, which separates the Southern Alps from the Central Alps, runs through South Tyrol in a southwest–northeast direction. In South Tyrol at least three of the four main structural elements of the Alps come to light: the Southern Alpine comes to light south of the periadriatic suture, the Eastern Alpine north of it, and in the northern part of the country, east of the Brenner Pass, the Tauern window, in which the Peninsular and, according to some authors, the Helvetic are visible.[33]

In South Tyrol, the following structure can be roughly recognized: The lowest floor forms the crystalline basement. About 280 million years ago, in the Lower Permian, multiple magmatic events occurred. At that time the Brixen granite was formed at the northern boundary of the Southern Alps, and at about the same time, further south in the Bolzano area, there was strong volcanic activity that formed the Adige Valley volcanic complex. In the Upper Permian a period began in which sedimentary rocks were formed. At first, these were partly clastic sediments, among which the Gröden sandstone is found. In the Triassic, massive carbonate platforms of dolomitic rocks then formed; this process was interrupted in the Middle Triassic by a brief but violent phase of volcanic activity.

In South Tyrol, the Eastern Alps consist mainly of metamorphic rocks, such as gneisses or mica schists, with occasional intercalations of marble and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks with metamorphic overprint (e.g., in the Ortler or southwest of the Brenner). Various metamorphic rocks are found in the Tauern Window, such as Hochstegen marble (as in Wolfendorn), Grünschiefer (as in Hochfeiler), or rocks of the Zentralgneiss (predominantly in the area of the Zillertal Main Ridge).[34]

The province of South Tyrol has placed numerous geological natural monuments under protection. Among the best known are the Bletterbach Gorge, a 12 km (7½ mile) long canyon in the municipality of Aldein, and the Ritten Earth Pyramids, which are the largest in Europe with a height of up to 30 متر (98 ft).[35]

Mountains

According to the Alpine Association, South Tyrol is home to 13 mountain groups of the Eastern Alps, of which only the Sarntal Alps are entirely within national borders. The remaining twelve are (clockwise, starting from the west): Sesvenna Group, Ötztal Alps, Stubai Alps, Zillertal Alps, Venediger Group, Rieserferner Group, Villgratner Mountains, Carnic Alps, Dolomites, Fleimstal Alps, Nonsberg Group and Ortler Alps. Of particular note are the Dolomites, parts of which were recognized by UNESCO in 2009 as a "Dolomite World Heritage Site".

Although some isolated massifs approach 4،000 متر (13،000 ft) and show strong glaciation (especially in the Ortler Alps and on the main ridge of the Alps), South Tyrol is by far dominated by mountains with altitudes of between 2،000 و 3،000 متر (6،600 و 9،800 ft). Among the multitude of peaks, the Dolomites are the highest in the Alps. Among the large number of peaks, three stand out for their alpine or cultural importance: the Ortler (3،905 متر، 12،812 ft) as the highest mountain in South Tyrol, the Schlern (2،563 متر، 8،409 ft) as the country's "landmark" and the Drei Zinnen (2،999 متر، 9،839 ft) as the center of alpine climbing. Other well-known mountains are the Königspitze (3،851 متر، 12،635 ft), the Weißkugel (3،739 متر، 12،267 ft), the Similaun (3،599 متر، 11،808 ft), the Hochwilde (3،480 متر، 11،417 ft), the Sarner Weißhorn (2،705 متر، 8،875 ft), the Hochfeiler (3،509 متر، 11،512 ft), the Dreiherrnspitze (3،499 متر، 11،480 ft), the Hochgall (3،436 متر، 11،273 ft), the Peitlerkofel (2،875 متر، 9،432 ft), the Langkofel (3،181 متر، 10،436 ft) and the Rosengartenspitze (2،981 متر، 9،780 ft).

The extensive mountain landscapes, about 34% of the total area of South Tyrol, are alpine pastures (including the 57 متر كيلومربع (22 sq mi) of the great Alpe di Siusi). Along the main valleys, the mountain ranges descend in many places to valley bottoms over gently terraced landscapes, which are geological remains of former valley systems; situated between inhospitable high mountains and formerly boggy or deeply incised valley bottoms, these areas known as the "Mittelgebirge" (including, for example, the Schlern area) are of particular importance in terms of settlement history.[36]

Valleys

The three main valleys of South Tyrol are the Adige Valley, the Eisack Valley and the Puster Valley, formed by the Ice Age Adige glacier and its tributaries. The highest part of the Adige valley in western South Tyrol, from Reschen (1،507 متر أو 4،944 أقدام) to Töll (approx. 500 متر أو 1،600 أقدام) near Merano, is called Vinschgau; the southernmost section, from Bolzano to Salurner Klause (207 متر أو 679 أقدام), is divided into Überetsch and Unterland. From there, the Adige Valley continues in a southerly direction until it merges with the Po plain at Verona.

At Bolzano, the Eisack Valley merges into the Adige Valley. The Eisack Valley runs from Bolzano northeastward to Franzensfeste, where it merges with the Wipp Valley, which runs first northwestward and then northward over the Brenner Pass to Innsbruck. In the town of Brixen, the Eisack Valley meets the Puster Valley, which passes through Bruneck and reaches Lienz via the Toblacher Sattel (1،210 متر أو 3،970 أقدام). In addition to the three main valleys, South Tyrol has a large number of side valleys. The most important and populated side valleys are (from west to east) Sulden, Schnals, Ulten, Passeier, Ridnaun, the Sarntal, Pfitsch, Gröden, the Gadertal, the Tauferer Ahrntal and Antholz.

In mountainous South Tyrol, about 64.5% of the total land area is above 1،500 متر (4،900 ft) above sea level and only 14% below 1،000 متر (3،300 ft).[37] Therefore, a large part of the population is concentrated in relatively small areas in the valleys at an altitude of between 100 و 1،200 متر (330 و 3،940 ft), mainly in the area of the extensive alluvial cones and broad basins. The most densely populated areas are in the Adige valley, where three of the four largest cities, Bolzano, Merano and Laives, are located. The flat valley bottoms are mainly used for agriculture.

Hydrography

The most important river in South Tyrol is the Adige, which rises at the Reschen Pass, flows for a distance of about 140 كيلومتر (87 mi) to the border at the Salurner Klause, and then flows into the Po Valley and the Adriatic Sea. The Adige, whose total length of 415 كيلومتر (258 mi) in Italy is exceeded only by the Po, drains 97% of the territory's surface area. Its river system also includes the Eisack, about 100 كيلومتر (62 mi) long, and the Rienz, about 80 كيلومتر (50 mi) long, the next two largest rivers in South Tyrol. They are fed by numerous rivers and streams in the tributary valleys. The most important tributaries are the Plima, the Passer, the Falschauer, the Talfer, the Ahr and the Gader. The remaining 3% of the area is drained by the Drava and Inn river systems to the Black Sea and by the Piave river system to the Adriatic Sea, respectively.[38]

In South Tyrol there are 176 natural lakes with an area of more than half a hectare (1¼ acre), most of which are located above 2،000 متر (6،600 ft) altitude. Only 13 natural lakes are larger than 5 ha, and only three of them are situated below 1،000 متر (3،300 ft) altitude: the Kalterer See (215 متر، 705 ft), the Großer (492 متر، 1،614 ft) and the Kleiner Montiggler See (514 متر، 1،686 ft). Fourteen South Tyrolean reservoirs used for energy production include the Reschensee (1،498 متر، 4،915 ft), which with an area of 523 هكتار (2.02 sq mi) forms the largest standing body of water in South Tyrol, the Zufrittsee (1،850 متر، 6،070 ft) and the Arzkarsee (2،250 متر، 7،382 ft).

The natural monuments designated by the province of South Tyrol include numerous hydrological objects, such as streams, waterfalls, moors, glaciers and mountain lakes like the Pragser Wildsee (1،494 متر، 4،902 ft), the Karersee (1،519 متر، 4،984 ft) or the Spronser Seen (2،117–2،589 متر، 6،946–8،494 ft).[39]

Vegetation

Approximately 50% of the area of South Tyrol is covered by forests,[40] another 40% is above 2،000 متر (6،600 ft) and thus largely beyond the forest demarcation line, which varies between 1،900 و 2،200 متر (6،200 و 7،200 ft). In each case, more than half of the total forest area is located on land with a slope steeper than 20° and at altitudes between 1،200 و 1،800 متر (3،900 و 5،900 ft). Approximately 24% of the forest area can be classified as protective forest preserving settlements, traffic routes and other human infrastructure. A 1997 study classified about 35% of South Tyrol's forests as near-natural or natural, about 41% as moderately modified and about 24% as heavily modified or artificial. The forests are found in the valley bottoms.

The flat valley bottoms were originally completely covered with riparian forests, of which only very small remnants remain along the rivers. The remaining areas have given way to settlements and agricultural land. On the valley slopes, sub-Mediterranean mixed deciduous forests are found up to 800 أو 900 متر (2،600 أو 3،000 ft) altitude, characterized mainly by manna ash, hop hornbeam, hackberry, sweet chestnut and downy oak. From about 600 متر (2،000 ft) of altitude, red beech or pine forests can appear instead, colonizing difficult and arid sites (more rarely). At altitudes between 800 و 1،500 متر (2،600 و 4،900 ft), spruce forests are found; between 900 و 2،000 متر (3،000 و 6،600 ft), montane and subalpine spruce forests predominate. The latter are often mixed with tree species such as larch, rowan, white pine and stone pine. The larch and stone pine forests at the upper edge of the forest belt occupy relatively small areas. Beyond the forest edge, subalpine dwarf shrub communities, alpine grasslands and, lately, alpine tundra dominate the landscape as vegetation types.[41]

السياسة

Since the end of the Second World War, the political scene of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano has been dominated by the Südtiroler Volkspartei (SVP). Since its foundation, the SVP has consistently held a majority in the Provincial Council (an absolute majority until the elections of 27 October 2013) and has always provided the provincial governor, most members of the provincial government, as well as the mayors of the vast majority of South Tyrolean municipalities. Ideologically, it is a centrist party with Christian-democratic and Christian-social roots, but in practice it functions as a “big tent” (Sammelpartei in German), gathering the support of most German- and Ladin-speaking citizens, while remaining formally open to anyone. The SVP usually governs alone or in alliance with civic lists in smaller municipalities. In towns with stronger Italian-speaking populations, and at national or European level, it historically allied with Christian Democracy; after its collapse, it reached agreements first with center-left coalitions and later with the Democratic Party, while always maintaining full political autonomy.

By the late 20th and early 21st century, the Die Freiheitlichen (“The Libertarians”) emerged as the second party in South Tyrol. Founded in 1992 and inspired by Austria’s Freedom Party, they position themselves on the right, focusing on defending South Tyrolean identity against what they see as outside influences. They call for stricter limits on immigration, hold conservative stances on civil rights (opposing gender quotas and the demands of the LGBT community), and are the strongest advocates of outright secession of South Tyrol from Italy to form a sovereign state. At times, they have collaborated at national level with the Lega Nord.

More radical secessionist positions are represented by Süd-Tiroler Freiheit (“South Tyrolean Freedom”), founded in 2007 by Eva Klotz, a leading figure of South Tyrolean irredentism, and the Bürger Union für Südtirol (formerly Union für Südtirol). Both movements call for the province’s reunification with Austria and demand stronger protection for the German- and Ladin-speaking population. Though generally placed on the right, they prefer not to define themselves in rigid ideological terms. Together, independence-oriented parties have at times reached close to 30% of the vote in provincial elections. Except for Die Freiheitlichen, they usually abstain from fielding candidates in Italian national elections, as a way of rejecting Rome’s authority over South Tyrol.

On the left, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Südtirols (Social Democratic Party of South Tyrol) briefly existed between 1973 and 1981, born from the left wing of the SVP but soon reabsorbed by it. Since the late 20th century, moderate left-wing voters have been represented within the SVP itself through the Arbeitnehmer faction. Longer-lasting has been the Verdi del Sudtirolo (South Tyrolean Greens), founded in 1978 by Alexander Langer. An ecological party, the Greens also emphasize interethnic cooperation among the province’s language groups and have gradually established themselves as the province’s third political force.

Within the Italian-speaking community, Christian Democracy and the Italian Social Movement were long dominant until their dissolution. In the 2003 provincial elections, Alleanza Nazionale was the strongest Italian party; in 2008, Il Popolo della Libertà took that position, though with fewer votes than Alleanza Nazionale and Forza Italia had gained combined. The 2013 provincial elections saw a collapse of the Italian center-right, divided into multiple lists, and the Democratic Party emerged as the strongest Italian party. In 2018, however, Italian-speaking voters shifted back to the right, with the Lega Nord becoming both the largest Italian party and the third-largest overall in South Tyrol.

As for the Ladin community, the Moviment Politich Ladins represents Ladin-specific interests, though with modest results, since most Ladins continue to find representation within the SVP, which maintains a dedicated Ladin section.

The local government system is based upon the provisions of the Italian Constitution and the Autonomy Statute of the Region Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol.[42] The 1972 second Statute of Autonomy for Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol devolved most legislative and executive competences from the regional level to the provincial level, creating de facto two separate regions.

The considerable legislative power of the province is vested in an assembly, the Landtag of South Tyrol (German: Südtiroler Landtag; Italian: Consiglio della Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano; Ladin: Cunsëi dla Provinzia Autonoma de Bulsan). The legislative powers of the assembly are defined by the second Statute of Autonomy.

The executive powers are attributed to the government (German: Landesregierung; Italian: Giunta Provinciale) headed by the Landeshauptmann Arno Kompatscher.[43] He belongs to the South Tyrolean People's Party, which has been governing with a parliamentary majority since 1948. South Tyrol is characterized by long sitting presidents, having only had two presidents between 1960 and 2014 (Silvius Magnago 1960–1989, Luis Durnwalder 1989–2014).

A fiscal regime allows the province to retain a large part of most levied taxes, in order to execute and administer its competences. Nevertheless, South Tyrol remains a net contributor to the Italian national budget.[44]

الانتخابات المحلية المؤخرة

| |||||

| الحزب | الأصوات | % | المقاعد | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Tyrolean People's Party | 97٬092 | 34.53 | 13 | −2 | |

| Team K | 31٬201 | 11.09 | 4 | −2 | |

| South Tyrolean Freedom | 30٬583 | 10.88 | 4 | +2 | |

| Greens | 25٬445 | 9.05 | 3 | ±0 | |

| Brothers of Italy | 16٬747 | 5.96 | 2 | +1 | |

| JWA List | 16٬596 | 5.90 | 2 | New | |

| Die Freiheitlichen | 13٬836 | 4.92 | 2 | ±0 | |

| Democratic Party | 9٬707 | 3.45 | 1 | ±0 | |

| For South Tyrol with Widmann | 9٬646 | 3.43 | 1 | ±0 | |

| League–United for Alto Adige | 8٬541 | 3.04 | 1 | −3 | |

| La Civica | 7٬301 | 2.60 | 1 | New | |

| Vita | 7٬222 | 2.57 | 1 | New | |

| Five Star Movement | 2٬086 | 0.74 | – | −1 | |

| Enzian | 1٬990 | 0.71 | – | New | |

| Forza Italia | 1٬625 | 0.58 | – | ±0 | |

| Centre-Right | 1٬601 | 0.57 | – | New | |

| الإجمالي | 281٬219 | 100.00 | 35 | – | |

| الأصوات الصحيحة | 281٬219 | 96.87 | |||

| الأصوات الباطلة/الفارغة | 9٬080 | 3.13 | |||

| إجمالي الأصوات | 290٬299 | 100.00 | |||

| الأصوات المسجلة/المشاركة | 429٬841 | 67.54 | |||

| المصدر: Official Results | |||||

قائمة الحكام

Provincial government

The provincial government (Landesregierung) of South Tyrol (formerly also called provincial committee, Giunta provinciale in Italian, Junta provinziala in Ladin) consists of a provincial governor and a variable number of provincial councilors. Currently (2021), the provincial government consists of eight provincial councilors and the provincial governor. The deputies of the provincial governor are appointed from among the provincial councilors. The current governor is Arno Kompatscher (SVP), his deputies are the provincial councilors Arnold Schuler (SVP), Giuliano Vettorato (LN) and Daniel Alfreider (SVP).

The Governor and the Provincial Councilors are elected by Parliament by secret ballot with an absolute majority of votes. The composition of the provincial government must in any case reflect the proportional distribution of the German and Italian language groups in the provincial parliament. In the past, this provision prevented the German-dominated South Tyrol People's Party (SVP) from governing alone and allowed Italian parties to participate in the provincial government. Since the Ladin language group, with just under 4% of South Tyrol's resident population, has little electoral potential, a separate provision in the autonomy statute allows Ladin representation in the provincial government regardless of their proportional representation in the provincial parliament.

Municipal administrations

The use of the proportional system (considered an appropriate tool to reflect the province’s ethnic composition) also applies to the election of municipal councillors, which in South Tyrol is technically separate from that of the mayor. In municipalities with fewer than 15,000 inhabitants, the mayor is the candidate who obtains a relative majority of votes (counting both those for the list and those cast directly for the candidate), while in municipalities with more than 15,000 inhabitants, the winner must surpass 50% of the vote; otherwise, a runoff is held. In both cases, the list or coalition of the winning candidate is not granted any majority bonus.

This can lead to cases of “minority mayors”: in 2010 in Dobbiaco, the SVP failed to agree on a single list and therefore decided to run with two separate groups, each with its own candidate. Combined, they retained an absolute majority of councillors, but lost the mayoralty to the civic list Indipendenti–Unabhängige of Guido Bocher, who obtained a relative majority and was therefore elected mayor. Bocher initially found himself in the minority within the municipal council but later secured the SVP’s confidence, forming a coalition administration with his list. The same pattern repeated in 2015, when Bocher defeated the SVP candidate by a wide margin, even though the SVP still held the largest share of seats in the council; for the following five years, the coalition scheme continued.

A similar scenario has also occurred in larger cities: in 2005 in Bolzano, center-right candidate Giovanni Benussi won the runoff but failed to obtain the confidence of the municipal council (which had a center-left majority supported by the SVP), and was therefore forced to resign. In 2020 in Merano, incumbent mayor Paul Rösch was re-elected for a second term, but his lists did not gain a majority in the council and no agreement could be reached to broaden the coalition, forcing him likewise to resign.

الحركة الانفصالية

Given the region's historical and cultural association with neighboring Austria, calls for the secession of South Tyrol and its reunification with Austria have surfaced from time to time among minor groups of German speakers; however, most of the population of South Tyrol does not support a separation.[45] Among the political parties that support South Tyrol's reunification into Austria are South Tyrolean Freedom, Die Freiheitlichen and Citizens' Union for South Tyrol.[46]

الاقتصاد

In 2023 South Tyrol had a GDP per capita of €62,100, making it the richest province in Italy and one of the richest in the European Union.[47][48]

The unemployment level in 2007 was roughly 2.4% (2.0% for men and 3.0% for women). Residents are employed in a variety of sectors, from agriculture — the province is a large producer of apples, and its South Tyrol wine are also renowned — to industry to services, especially tourism. Spas located on the Italian Alps have become a favorite for tourists seeking wellness.[49]

South Tyrol is home to numerous mechanical engineering companies, some of which are the global market leaders in their sectors: the Leitner Group that specializes in cable cars and wind energy, TechnoAlpin AG, which is the global market leader in snow-making technology and the snow groomer company Prinoth.

The unemployment rate stood at 2% in 2024.[50]

النقل

Road transport

South Tyrol has a well-developed road network over 5,000 km in length. The most important transport infrastructure is the toll-based Brenner Motorway (A22), also called the Autostrada del Brennero, part of the European Route E45. It also connects to the Brenner Autobahn in Austria. It runs through the region in a north–south direction from the Brenner Pass (1,370 m) past Brixen and Bolzano to the Salurner Klause (207 m). The Brenner is the Alpine pass with the highest volume of freight traffic.[51] In 2023, an average of 25,440 cars and 13,187 trucks traveled on the A22 each day.[52] The region is, together with northern and eastern Tyrol, an important transit point between southern Germany and Northern Italy. The vehicle registration plate of South Tyrol is the two-letter provincial code Bz for the capital city, Bolzano. Along with the autonomous Trentino (Tn) and Aosta Valley (Ao), South Tyrol is allowed to surmount its license plates with its coat of arms.

The key towns, valleys, and passes of South Tyrol are connected by state and provincial roads, which since 1998 have been exclusively maintained and financed by the South Tyrolean provincial administration. In addition, there are numerous municipal roads. The busiest roads are the major state roads, particularly in the more densely populated areas. On the SS 38 serving the west of the region, which between Merano and Bolzano has been expanded into a four-lane expressway known as the MeBo, more than 41,000 daily journeys were recorded around Bolzano in 2024. The SS 42, which connects Bolzano with the Überetsch area, registered more than 24,000 daily journeys, the SS 12 (“Brenner State Road”) running parallel to the motorway at the entrance to the Eisack Valley had more than 20,000, and the SS 49 in the Puster Valley recorded more than 21,000 on some sections.

The mountainous terrain of South Tyrol requires a large number of complex engineering structures. On state and provincial roads alone, there are about 1,700 bridges and 208 tunnels.[53] Mountain passes accessible to general motor traffic are particularly maintenance-intensive. Seven of these pass roads rise above 2,000 m in elevation, namely the Stelvio Pass (2,757 m), Timmelsjoch (2,474 m), Sella Pass (2,218 m), Penser Joch (2,211 m), Gardena Pass (2,121 m), Jaufen Pass (2,094 m), and Staller Sattel (2,052 m).

Rail transport

The South Tyrolean rail network covers about 300 km of track. It is partly operated by Rete Ferroviaria Italiana and partly by South Tyrolean Transport Structures.

The Brenner Railway, part of the Berlin–Palermo axis, connects Innsbruck via Bolzano and Trento with Verona, crossing the region in a north–south direction. The Brenner Base Tunnel (BBT), currently under construction and expected to open in 2032, will run beneath the Brenner Pass, shifting much of the freight transit from road to rail. With a planned length of 55 كيلومتر (34 mi), this tunnel will increase freight train average speed to 120 كيلومترات في الساعة (75 mph) and reduce transit time by over an hour.[54] Western South Tyrol is served by the Bolzano–Merano line and the Vinschgau Railway, while the Puster Valley Railway links Franzensfeste with Innichen and further connects to the Drava Valley Railway in Austrian East Tyrol. In addition, there are several smaller railways of primarily tourist significance, such as the Ritten Railway and the Mendel funicular. Some branch lines, including the Überetsch Railway and Taufers Railway, were closed between 1950 and 1971 with the rise of automobile traffic. Larger cities used to have their own tramway system, such as the Meran Tramway and Bolzano Tramway. These were replaced after the Second World War with buses. Many other cities and municipalities have their own bus system or are connected with each other by it.

Long-distance domestic and international passenger services operate in South Tyrol only on the Brenner Railway. Cross-border regional passenger services exist on both the Brenner and Puster Valley railways. Freight traffic is also carried exclusively on the Brenner Railway, with around 11.7 million tonnes of goods transported in 2013.[55]

Bicycle, cableway, and air transport

The inter-municipal cycling network has been steadily expanded for years and now covers more than 500 km.[56] The three main cycling routes through the region’s major valleys—Route 1 “Brenner–Salurn,” Route 2 “Vinschgau–Bolzano,” and Route 3 “Puster Valley”—are almost entirely continuous. Within Bolzano alone, the cycling network includes about 50 km of designated paths, accounting for around 30% of urban trips.

In 2024, South Tyrol had 354 cable car installations. Most serve winter sports areas, though some are also used for public transport. More than half of the installations were built after 2000.

Bolzano Airport is used for scheduled flights, charter flights, general aviation, and military purposes. There is also Toblach Airfield, which is primarily military but also partly open to private users.

Cable car on Mount Seceda in the Dolomites

Public transport

All public transport in South Tyrol is integrated into the Verkehrsverbund Südtirol (South Tyrol Integrated Transport System). More than half of South Tyroleans have a South Tyrol Pass (Südtirol Pass), which allows contactless validation and travel on all network services.[57] These include intercity and urban buses (such as SASA), regional trains operated by SAD and Trenitalia, the Mendel and Ritten railways, and cable cars to Kohlern, Meransen, Mölten, Ritten, and Vöran.

During the 2000s, the province of South Tyrol significantly expanded and improved the frequency of bus and train services. With the gradual introduction of the so-called South Tyrol Takt (timetable system), half-hourly or hourly services were established on the main routes, with denser services at peak times and improved coordination between bus and rail.

الديموغرافيا

اللغات

| لغات جنوب التيرول الأقليات لكل بلدية في 2011: | |

|---|---|

| |

| اللغات الرسمية | |

| المصدر | astat Jahrbuch 2024 |

| السنة | تعداد | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 254٬735 | — |

| 1931 | 282٬158 | +10.8% |

| 1951 | 333٬900 | +18.3% |

| 1961 | 373٬863 | +12.0% |

| 1971 | 414٬041 | +10.7% |

| 1981 | 430٬568 | +4.0% |

| 1991 | 440٬508 | +2.3% |

| 2001 | 462٬999 | +5.1% |

| 2011 | 504٬643 | +9.0% |

| 2021 | 532٬616 | +5.5% |

| Source: ISTAT | ||

German and Italian are both official languages of South Tyrol. In some eastern municipalities Ladin is the third official language.

A majority of the inhabitants of contemporary South Tyrol speak the native Southern Bavarian dialect of the German language. Standard German plays a dominant role in education and media. All citizens have the right to use their own mother tongue, even at court. Schools are separated for each language group. All traffic signs are officially bi- or trilingual. Most Italian place names were translated from German by Italian Ettore Tolomei, the author of the Prontuario dei nomi locali dell'Alto Adige.[58]

At the time of the annexation of the southern part of Tyrol by Italy in 1920, the overwhelming majority of the population spoke German: in 1910, according to the last population census before World War I, the German-speaking population numbered 224,000, the Ladin 9,000 and the Italian 7,000.[10]

At the 2024 census, German speakers made up 68.61% of the province's Italian citizens,[59] or 57.6% when considering the total population of the autonomous province. In private and public life within the German-speaking community, an Alpine Austro-Bavarian dialect (the South Tyrolean dialect) predominates, characterized by a certain presence of Romance-derived vocabulary. Standard German in its Austrian variant remains the language taught in schools, used in written communication, and in official settings. The German-speaking group is the majority in 102 out of 116 municipalities (reaching as high as 99.52% in Moos in Passeier); in as many as 75 of these municipalities, the German language group constitutes more than 90% of residents.

According to the 2024 ASTAT language census, 26.98% of the Italian citizens who are residents of South Tyrol are Italian-speakers[60] (they were 33.31%, 138,000 of 414,000 inhabitants in 1971), or 22.6% when considering the total population of the autonomous province.[61] The Italian-speaking population lives mainly around the provincial capital Bolzano, where they are the majority (74.7% of the inhabitants). The other five municipalities where the Italian-speaking population is the majority are Merano (51.37%), Laives (74.47%), Salorno (62.49%), Bronzolo (63.46%) and Vadena (61.52%). Italian speakers, coming from various regions, use mainly Standard Italian in daily life, while in the South of South Tyrol (Bassa Atesina) the Trentino dialect is also common.[62]

About 4.4% of South Tyroleans are native speakers of Dolomite Ladin, mainly in Val Gardena and Val Badia, where they form the majority in La Val, San Martin de Tor, Mareo, Badia, Santa Cristina Gherdëina, Sëlva, Corvara, and Urtijëi (with La Val reaching 96.45%).

At the time of the decennial population census, every citizen over the age of 14 is required to declare their belonging to one of the three language groups. Based on the results, positions in public employment, public housing, and subsidies for institutions and associations are allocated according to the ethnic proportional system. Schools are organized separately for each language group. Even some associations attract members predominantly from only one linguistic group, such as the Club Alpino Italiano and the Alpenverein Südtirol, and even Caritas maintains separate sections.

With regard to schooling in particular, teaching is provided exclusively in either Italian or German, according to linguistic affiliation, by native-speaking teachers. A mitigating element is the learning of the other language beginning in the first or second year of primary school (as if it were a foreign language). At the level of the provincial government, there are three distinct departments: one each for German-language, Italian-language and Ladin-language education.

| Year | Italian speakers | German speakers | Ladin speakers | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 6,884 (3.4%) | 186,087 (90.6%) | 8,822 (4.3%) | 3,513 (1.7%) | 205,306 |

| 1890 | 9,369 (4.5%) | 187,100 (89.0%) | 8,954 (4.3%) | 4,862 (2.3%) | 210,285 |

| 1900 | 8,916 (4.0%) | 197,822 (88.8%) | 8,907 (4.0%) | 7,149 (3.2%) | 222,794 |

| 1910 | 7,339 (2.9%) | 223,913 (89.0%) | 9,429 (3.8%) | 10,770 (4.3%) | 251,451 |

| 1921 | 27,048 (10.6%) | 193,271 (75.9%) | 9,910 (3.9%) | 24,506 (9.6%) | 254,735 |

| 1931[64] | 65,503 (23.2%) | 195,177 (69.2%) | n.a. | 21,478 (7,6%) | 282,158[65] |

| 1953 | 114,568 (33.1%) | 214,257 (61.9%) | 12,696 (3,7%) | 4,251 (1.3%) | 345,772[66] |

| 1961 | 128,271 (34.3%) | 232,717 (62.2%) | 12,594 (3.4%) | 281 (0.1%) | 373,863 |

| 1971 | 137,759 (33.3%) | 260,351 (62.9%) | 15,456 (3.7%) | 475 (0.1%) | 414,041 |

| 1981 | 123,695 (28.7%) | 279,544 (64.9%) | 17,736 (4.1%) | 9,593 (2.2%) | 430,568 |

| 1991 | 116,914 (26.5%) | 287,503 (65.3%) | 18,434 (4.2%) | 17,657 (4.0%) | 440,508 |

| 2001 | 113,494 (24.5%) | 296,461 (64.0%) | 18,736 (4.0%) | 34,308 (7.4%) | 462,999 |

| 2011 | 118,120 (23.3%) | 314,604 (62.2%) | 20,548 (4.0%) | 51,795 (10.5%) | 505,067 |

| 2024 | 121,520 (22.6%) | 309,000 (57.6%) | 19,853 (3.7%) | 86,560 (16.1%) | 536,933 |

The linguistic breakdown of residents with Italian citizenship according to the census of 2024:[67]

| Language | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| German | 309,000 | 68.61% |

| Italian | 121,520 | 26.98% |

| Ladin | 19,853 | 4.41% |

| Total | 450,373 | 100% |

الديانات

The majority of the population is Christian, mostly in the Catholic tradition. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Bolzano-Brixen corresponds to the territory of the province of South Tyrol. Since 27 July 2011 the bishop of Bolzano-Brixen is Ivo Muser.

Catholic Church

The vast majority of the population of South Tyrol is baptized Catholic. There is archaeological evidence of early Christian sites in the area as early as Late Antiquity;[68] Säben in the Eisack Valley became an important ecclesiastical center during this period, which was only replaced by Brixen as an episcopal see in the late Middle Ages. The territory of present-day South Tyrol was divided for centuries between the dioceses of Brixen, Chur (until 1808/1816) and Trent (until 1964).[69]

The most famous bishop of Brixen was the polymath Nicholas of Cusa. Important figures of the regional ecclesiastical life in the 19th century were the beatified bishop of Trent Johann Nepomuk von Tschiderer and the mystic Maria von Mörl.

In 1964, with reference to modern political boundaries, the Bishopric of Brixen, which had lost its extensive territories of North and East Tyrol after World War I, was enlarged to form the Diocese of Bolzano-Brixen, whose extension is now identical to that of the province of South Tyrol. Since then, the faithful have been led by Bishops Joseph Gargitter (1964-1986), Wilhelm Egger (1986-2008), Karl Golser (2008-2011) and Ivo Muser (since 2011). The diocese comprises 28 deaneries and 281 parishes (in 2014), 23 its episcopal churches are the Cathedral of Brixen and the Cathedral of Bolzano. Cassian and Vigilius are venerated as diocesan patrons.[70] Important references in the current discourses of the local Catholic Church are St. Joseph Freinademetz and Blessed Joseph Mayr-Nusser.

Other communities

There is a Lutheran community in Merano (founded 1861) and another one in Bolzano (founded 1889). Since the Middle Ages the Jewish presence has been documented in South Tyrol. In 1901 the Synagogue of Merano was built. As of 2015, South Tyrol was home to about 14,000 Muslims.[71]

الثقافة

Traditions

South Tyrol has long-standing traditions, mainly inherited from its membership in the historical Tyrol. The Schützen associations are particularly fond of Tyrolean traditions.

The Scheibenschlagen are the traditional "throwing of burning discs" on the first Sunday of Lent, the Herz-Jesu-Feuer are the "fires of the Sacred Heart of Jesus" that are lit on the third Sunday after Pentecost. The Krampus are disguised demons who accompany St Nicholas.

There are also several legends and sagas linked to the peoples of the Dolomites; among the best known are the legend of King Laurin and that of the Kingdom of Fanes, which belongs to the Ladin mythological heritage.

Alpine Transhumance (from German Almabtrieb), is a farm practice: every year, between September and October, the livestock that stayed on the high pastures is brought back to the valley, with traditional music and dances. Especially, the transhumance between the Ötztal (in Austria) and Schnals Valley and Passeier Valley was recognised by UNESCO as universal intangible heritage in 2019.[72]

التعليم

Universities

In terms of higher education, the University of Innsbruck, founded in 1669, has traditionally been regarded as the “regional university” for the federal state of Tyrol, South Tyrol, Vorarlberg, and the Principality of Liechtenstein. In South Tyrol, the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano (FUB) was established from 1997 as a complementary institution. It has three campuses (Bozen, Brixen, and Bruneck), housing the faculties of Economics, Computer Science, Design and Arts, Natural Sciences and Engineering, and Education. In addition to the FUB, institutions such as the Philosophical-Theological College of Brixen, the Claudiana University College for Health Professions, and the “Claudio Monteverdi” Conservatory in Bozen provide specialized higher education. The largest representative body for South Tyrolean students is sh.asus.

العمارة

The region features a large number of castles and churches. Many of the castles and Ansitze were built by the local nobility and the Habsburg rulers. See List of castles in South Tyrol.

المتاحف

South Tyrol’s museum offerings are wide-ranging. About half of the institutions are privately run, the other half by public bodies or church institutions. The eleven South Tyrolean provincial museums, which are culturally, naturally, and historically oriented, record strong visitor numbers and are in part spread across multiple sites in South Tyrol:

- the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, which has the mummy of Ötzi the Iceman

- the Museion, Museum of modern and contemporary art of Bolzano

- the Messner Mountain Museum of Reinhold Messner

- the White Tower (Brixen) museum

- the South Tyrol Mining Museum

- the Eccel Kreuzer Museum

- the Fortress of Franzensfeste

- the South Tyrol Museum of Hunting and Fishing

- the South Tyrol Museum of Culture and Provincial History

- the Museum Ladin

- the South Tyrol Museum of Nature

- the Touriseum with the adjoining gardens of Trauttmansdorff Castle

- the South Tyrol Museum of Folklore

- the South Tyrol Wine Museum

Other institutions with private, church, or mixed sponsorship include, for example, the Messner Mountain Museum initiated by Reinhold Messner on the theme of “mountain,” the Diocesan Museum of Brixen with its collection of Christian art from the Middle Ages and modern times, the Pharmacy Museum in Brixen, and the Museion, the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Bozen, which is jointly run by an association and the province.

Libraries

There are about 280 public libraries in South Tyrol, which are affiliated with many privately run institutions in the South Tyrolean Library Network. Two scholarly libraries stand out in importance and size: the “Dr. Friedrich Teßmann” Provincial Library with its comprehensive Tyrolensia collection, and the library of the Free University of Bozen, which is spread across three locations. Since 1997, the project “Cataloguing Historical Libraries” has been dedicated to indexing South Tyrol’s historical holdings.

Research institutions

The most important research institutions in South Tyrol are located at the Free University of Bozen and at Eurac Research. The university is mainly engaged in research within its faculties, i.e. economics, computer science, natural sciences, engineering, and education. The eleven institutes of Eurac Research, founded in 1992, work in an interdisciplinary way on the topics of autonomy, health, mountains, and technologies.

The Laimburg Research Centre is tasked with practice-oriented agricultural research. An Italian subsidiary of the Fraunhofer Society, founded in 2009, is based in the NOI Techpark in Bolzano. Historical source research is carried out, among others, by the South Tyrol Provincial Archives, the State Archives of Bolzano, and the City Archives of Bolzano. Further research facilities exist at the South Tyrolean Provincial Museums, such as the Centre for Regional History.

Health and social services

Healthcare

The publicly funded facilities of the healthcare system are centrally managed and coordinated by the South Tyrolean Health Authority (Südtiroler Sanitätsbetrieb). The authority includes seven hospitals: the central hospital in Bolzano, the major hospitals in Brixen, Bruneck, and Meran, as well as the basic care hospitals in Innichen (belonging to the Bruneck health district), Schlanders (belonging to the Meran health district), and Sterzing (belonging to the Brixen health district).[73] In addition, South Tyrol is divided into a number of smaller health districts (Gesundheitssprengel) with local clinics that provide services in prevention, diagnostics, therapy, rehabilitation, and counseling.[74] The health authority represents by far the largest item in South Tyrol’s regional budget: in 2024, it accounted for €1.57 billion.[75]

In addition to the public hospitals, there are also several accredited private clinics in Bolzano, Meran, and Brixen.

Social services

The main public providers of social services in South Tyrol are the district communities (Bezirksgemeinschaften), which have taken over this area of responsibility from the municipalities. Most social services—including financial assistance, home care, basic socio-educational support, and citizen services—are provided by the social districts (Sozialsprengel) distributed throughout the region, whose offices coincide with those of the health districts. However, some services are provided across districts for organizational reasons.

An important element of social policy is the South Tyrolean Housing Institute (Wohnbauinstitut, WOBI), founded in 1972 immediately after the adoption of the Second Statute of Autonomy. This public-law body is responsible for building and renting housing for low-income and middle-class families, elderly people, people with disabilities, as well as for providing dormitories for workers and students.[76] In 2015, WOBI managed 13,000 apartments in 112 municipalities.

Among the non-governmental providers of social services in South Tyrol are, among others, church organizations such as Caritas, associations such as the St. Vincent Society (Vinzenzgemeinschaft) and Lebenshilfe, as well as a variety of social cooperatives.

الإعلام

الموسيقى

The Bozner Bergsteigerlied and the Andreas-Hofer-Lied are considered to be the unofficial anthems of South Tyrol.[77]

The folk musical group Kastelruther Spatzen from Kastelruth and the rock band Frei.Wild from Brixen have received high recognition in the German-speaking part of the world.[citation needed]

Award-winning electronic music producer Giorgio Moroder was born and raised in South Tyrol in a mixed Italian, German and Ladin-speaking environment.

Cuisine =

Among the traditional dishes and foodstuffs of South Tyrol’s rural, grain-based cuisine were once wheat and oat porridge, later also polenta, as well as spelt and rye bread (for example Vinschgauer or Schüttelbrot). Commonly cultivated vegetables included cabbage, turnips, potatoes, and green beans. Due to widespread livestock farming, dairy products were available in abundance. Pork lard was primarily used as cooking fat. Meat was typically processed into smoked products (such as Speck or Kaminwurzen).

With the rise of tourism in the 1960s and 1970s, regional cuisine experienced a revival, for instance through the rapidly popularized tradition of Törggelen or the somewhat later “Specialties Weeks,” which sought to introduce tourists to local delicacies. In this process, traditional Tyrolean fare was adapted to modern preparation and processing techniques, and shaped by the influence of Italian cuisine to suit contemporary tastes. In gastronomy, roughly one-third of the offerings come from local cuisine, one-third from Italian cuisine, and one-third from the standard repertoire of international cuisine.

Typical South Tyrolean dishes include dumplings (Knödel), barley soup, schlutzkrapfen, strauben, tirteln, and cold-cut platters, which are often enjoyed with South Tyrolean wine as a Marende (traditional afternoon snack).

الرياضة

South Tyrolese have been successful at winter sports and they regularly form a large part of Italy's contingent at the Winter Olympics: in the last edition (2022), South Tyroleans won 3 out of the 17 Italian medals, all three bronzes (of which two won by German-speaking South Tyroleans). Famed mountain climber Reinhold Messner, the first climber to climb Mount Everest without the use of oxygen tanks, was born and raised in the region. Other successful South Tyrolese include luger Armin Zöggeler, figure skater Carolina Kostner, skier Isolde Kostner, luge and bobsleigh medallist Gerda Weissensteiner, tennis players Andreas Seppi and Jannik Sinner, and former team principal of Haas F1 Team in the FIA Formula One World Championship Guenther Steiner.

HC Interspar Bolzano-Bozen Foxes are one of Italy's most successful ice hockey teams, while the most important football club in South Tyrol is FC Südtirol, which won its first-ever promotion to Serie B in 2022.

The province is famous worldwide for its mountain climbing opportunities, while in winter it is home to a number of popular ski resorts including Val Gardena, Alta Badia and Seiser Alm.

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ English pronunciation: /tɪˈroʊl/ tirr-OHL, /taɪˈroʊl/ ty-ROHL or /ˈtaɪroʊl/ TY-rohl.[3]

- ^ ألمانية: Autonome Provinz Bozen – Südtirol؛ إيطالية: provincia autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige؛ Ladin: provinzia autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol.

المصادر

- ^ [1], Accessed on 1 November 2025.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ "Tyrol". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Autonomous Province of Bolzano/Bozen – South Tyrol". Autonomous Province Bolzano/Bozen – South Tyrol. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024.

- ^ [2] Archived 25 سبتمبر 2019 at the Wayback Machine Statuto speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige.

- ^ "Trentino-Alto Adige (Autonomous Region, Italy) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location".

- ^ "Risk of poverty or social exclusion in regions". ec.europa.eu (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2024-10-15. Retrieved 2025-06-19.

- ^ Cortina d'Ampezzo, Livinallongo/Buchenstein and Colle Santa Lucia, formerly parts of Tyrol, now belong to the region of Veneto.

- ^ "Statistisches Jahrbuch 2024 / statistico della Provincia di Bolzano 2024" (PDF). 03 Bevölkerung. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ أ ب Oscar Benvenuto (ed.): "South Tyrol in Figures 2008", Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol, Bozen/Bolzano 2007, p. 19, Table 11

- ^ Steininger, Rolf (2003). South Tyrol, A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0800-5.

- ^ Cf. for instance Antony E. Alcock, The History of the South Tyrol Question, London: Michael Joseph, 1970; Rolf Steininger, South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2003.

- ^ Bondi, Sandro (25 January 2011) (in it) (Letter), Lettera del ministro per i beni culturali Bondi al presidente del consiglio Durnwalder, Rome: Il Ministro per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, http://www.stol.it/content/download/152939/1808238/file/Der%20Bondi-Brief.pdf, retrieved on 4 June 2011

- ^ Cole, John (2003), "The Last Become First: The Rise of Ultimogeniture in Contemporary South Tyrol", in Grandits, Hannes, Distinct Inheritances: Property, Family and Community in a Changing Europe, Münster: Lit Verlag, p. 263, ISBN 3-8258-6961-X

- ^ "Cfr. for instance this article from britishcouncil.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2011.

- ^ Cisalpine Republic (1798). Raccolta delle leggi, proclami, ordini ed avvisi, Vol 5 (in الإيطالية). Milan: Luigi Viladini. p. 184.

- ^ Frederick C. Schneid (2002). Napoleon's Italian campaigns 1805–1815. Milan: Praeger Publishers. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-275-96875-5.

- ^ Steininger, Rolf (2003), South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, p. 21, ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4

- ^ Heiss, Hans (2003), "Von der Provinz zum Land. Südtirols Zweite Autonomie", in Solderer, Gottfried, Das 20. Jahrhundert in Südtirol. 1980 – 2000, V, Bozen/Bolzano: Raetia, p. 50, ISBN 978-88-7283-204-2

- ^ "Landesregierung | Autonome Provinz Bozen". Landesregierung.

- ^ "Provincia Autonoma Bolzano - Alto Adige" (in Italian). Bolzano: Provincia autonoma di Bolzano. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Provinzia Autonoma Bulsan - Südtirol" (in Ladin). Bolzano: Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan - Südtirol. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Hannes Obermair (2020). "Großdeutschland ruft!" Südtiroler NS-Optionspropaganda und völkische Sozialisation – "La Grande Germania chiamaǃ" La propaganda nazionalsocialista sulle Opzioni in Alto Adige e la socializzazione 'völkisch' (in الألمانية and الإيطالية). Tyrol Castle: South Tyrolean Museum of History. ISBN 978-88-95523-35-4.

- ^ "Caldonazzi, Walter". Austria-Forum.

- ^ Elisabeth Boeckl-Klamper, Thomas Mang, Wolfgang Neugebauer: Gestapo-Leitstelle Wien 1938–1945. Vienna 2018, ISBN 978-3-902494-83-2, pp. 299–305; Hans Schafranek: Widerstand und Verrat: Gestapospitzel im antifaschistischen Untergrund. Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-7076-0622-5, pp. 161–248; Fritz Molden: Die Feuer in der Nacht. Opfer und Sinn des österreichischen Widerstandes 1938–1945. Vienna 1988, p. 122; Christoph Thurner "The CASSIA Spy Ring in World War II Austria: A History of the OSS's Maier-Messner Group" (2017); Memorial dedicated to four brave Tyrolese resistance fighters

- ^ أ ب Danspeckgruber, Wolfgang F. (2002). The Self-Determination of Peoples: Community, Nation, and State in an Interdependent World. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 1-55587-793-1.

- ^ Anthony Alcock. "The South Tyrol Autonomy. A Short Introduction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Rolf Steininger: "South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century", Transaction Publishers, 2003, ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4, pp.2

- ^ "Tbilisi's S.Ossetia Diplomatic Offensive Gains Momentum". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ "Referendum Cortina, trionfo dei "sì" superato il quorum nei tre Comuni". La Repubblica. Rome. 29 October 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ Francesco Palermo (2021). "COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Italy's Governance and Security". PRISM. 9 (4): 9.

- ^ أ ب ت "South Tyrol in figures" (PDF). Provincial Statistics Institute (ASTAT). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 سبتمبر 2011. Retrieved 4 سبتمبر 2011.

- ^ "Entstehungsgeschichte - NaturStein Südtirol". www.naturstein-suedtirol.it. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Geologische Bundesanstalt: Geofast-Karten

- ^ SPA, Südtiroler Informatik AG | Informatica Alto Adige. "Natur, Landschaft und Raumentwicklung | Landesverwaltung | Autonome Provinz Bozen - Südtirol". Landesverwaltung (in الألمانية). Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Ernst Steinicke, Giuliana Andreotti: Das Pustertal. Geographische Profile im Raum von Innichen und Bruneck. In: Ernst Steinicke (Hrsg.): Europaregion Tirol, Südtirol, Trentino. Band 3: Spezialexkursionen in Südtirol. Institut für Geographie der Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck 2003, ISBN 3-901182-35-7, S. 14.

- ^ Reinhard Kuntzke, Christiane Hauch: Südtirol. DuMont Reise-Taschenbuch. Dumont Reiseverlag, Ostfildern 2012, ISBN 978-3-7701-7251-1, S. 44.

- ^ SPA, Südtiroler Informatik AG | Informatica Alto Adige. "Landesagentur für Umwelt und Klimaschutz | Autonome Provinz Bozen - Südtirol". Landesagentur für Umwelt und Klimaschutz (in الألمانية). Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ SPA, Südtiroler Informatik AG | Informatica Alto Adige. "Natur, Landschaft und Raumentwicklung | Landesverwaltung | Autonome Provinz Bozen - Südtirol". Landesverwaltung (in الألمانية). Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ "Südtirols Wald: Flächen | Abteilung Forstwirtschaft | Autonome Provinz Bozen - Südtirol". 2015-04-02. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ "Lebensgemeinschaft Wald | Abteilung Forstwirtschaft | Autonome Provinz Bozen - Südtirol". 2015-04-02. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ "Special Statute for Trentino-Alto Adige" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Mayr, Walter (25 August 2010). "The South Tyrol Success Story: Italy's German-Speaking Province Escapes the Crisis". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

Durnwalder's party, the South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP), ...has ruled the province with an absolute or relative majority since 1948.

- ^ "Dati Regionali 2012 shock: Residuo Fiscale (saldo attivo per 95 miliardi al Nord)". 27 May 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "South Tyrol heading to unofficial independence referendum in autumn". 7 March 2013. Nationalia.info. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "Website of South Tylorean Freedom". Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "Regional GDP in the European Union, 2016".

- ^ "ECONOMY IN FIGURES - THE ECONOMY IN SOUTH TYROL – CURRENT DATA, INDICATORS AND DEVELOPMENTS" (PDF). wifo.bz.it. Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Crafts, Tourism and Agriculture Bolzano/Bozen. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ Rysman, Laura (4 February 2019). "Italian Alpine Spas, Where Sports Are an Afterthought". NYT.

- ^ "Unemployment NUTS 2 regions Eurostat" (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "60 Prozent des Lkw-Alpentransits fahren über Österreich". Der Standard. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "Verkehr auf Teilstrecken der Brennerautobahn A22". eurac.edu. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "Verwaltung Tunnelbauten". Abteilung Straßendienst der Autonomen Provinz Bozen – Südtirol. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "The Brenner Base Tunnel". Brenner Basistunnel BBT SE. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Ungerboeck, Luise (17 July 2014). "Weniger Fracht rollt auf der Schiene über die Alpen". Der Standard. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "Radmobilität: Wichtige Investitionen für Südtirols Radwegenetz". Abteilung Natur, Landschaft und Raumentwicklung der Autonomen Provinz Bozen – Südtirol. 14 May 2025. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "Öffentlicher Nahverkehr: Landesregierung passt Ticket-Preise an". news.provinz.bz.it. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ Steininger, Rolf (2003), South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, pp. 21–46, ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4

- ^ "Risultati Censimento linguistico - 2024". Istituto provinciale di statistica ASTAT. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ Istituto provinciale di statistica ASTAT, Risultati Censimento linguistico - 2024.

- ^ Annuario statistico della provincia di Bolzano - 2024

- ^ "Notiziario Comunale Bronzolo". comune.bronzolo.bz.it. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Statistisches Jahrbuch für Südtirol 2025" (PDF). Landesinstitut für Statistik ASTAT (in الألمانية and الإيطالية) (41st ed.). Bolzano: Landesinstitut für Statistik der Autonomen Provinz Bozen – Südtirol. 2025.

- ^ Ribichini, Paolo (2009). Da Sudtirolo ad Alto Adige: arrivano gli italiani. Edizioni Associate. p. 16. ISBN 882670483X.

- ^ "Popolazione Provincia di Bolzano 1861-2016". comuni-italiani.it (in الإيطالية).

- ^ Finetto, Maria Teresa; Fraternali, Sandro; Zucal, Cristina (1998). Identità, persona, ambiente: percorsi didattici per il biennio della scuola superiore. Milan: FrancoAngeli. p. 275.

- ^ "Statistisches Jahrbuch für Südtirol 2024 / Annuario statistico della Provincia di Bolzano 2024" (PDF). 03 Bevölkerung. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ Leo Andergassen: Südtirol – Kunst vor Ort. Athesia, Bozen 2002, ISBN 88-8266-111-3, S. 7.

- ^ Heinrich Kofler: Geschichte des Dekanats Schlanders von seiner Errichtung im Jahr 1811 bis zur freiwilligen Demission von Dekan Josef Schönauer 1989. In: Marktgemeinde Schlanders (Hrsg.): Schlanders und seine Geschichte. Band 2: Von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart. Tappeiner, Lana 2010, ISBN 978-88-7073-531-4, S. 11–186, insbesondere S. 11–15 (PDF-Datei)

- ^ "Diözesanpatrone Hl. Kassian und Hl. Vigilius". Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Parteli, Elisabeth (15 January 2015). "Verdächtig religiös (German)". ff – Südtiroler Wochenmagazin, Nr. 4. pp. 36–47. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Transumance". Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "Krankenhäuser". Südtiroler Sanitätsbetrieb. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Die Gesundheitssprengel in Südtirol". Südtiroler Sanitätsbetrieb. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Haushaltsvoranschlag enthält Maßnahmen gegen Teuerung". salute.provincia.bz.it. 29 October 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Über uns". WOBI Bozen. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ Rainer Seberich (1979). "Singen unter dem Faschismus: Ein Untersuchungsbericht zur politischen und kulturellen Bedeutung der Volksliedpflege". Der Schlern, 50,4, 1976, pp. 209–218, here p. 212.

المراجع

- (بالألمانية) Gottfried Solderer (ed) (1999—2004). Das 20. Jahrhundert in Südtirol. 6 Vol., Bozen: Raetia Verlag. ISBN 978-88-7283-137-3

- Antony E. Alcock (2003). The History of the South Tyrol Question. London: Michael Joseph. 535 pp.

- Rolf Steininger (2003). South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4

- Georg Grote (2012). The South Tyrol Question 1866—2010. From National Rage to Regional State. Oxford: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-336-1

- Georg Grote, Hannes Obermair (2017). A Land on the Threshold. South Tyrolean Transformations, 1915—2015. Oxford/Bern/New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-0343-2240-9

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles containing إيطالية-language text

- Articles containing Ladin-language text

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 الإيطالية-language sources (it)

- CS1 foreign language sources (ISO 639-2)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages with ألمانية IPA

- Pages including recorded pronunciations

- Pages with Austrian German IPA

- Pages with إيطالية IPA

- Pages using bar box without float left or float right

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2013

- بلديات جنوب التيرول

- جنوب التيرول

- مناطق في أوروپا بلغات رسمية متعددة

- مقاطعات حكم ذاتي

- بلدان وأراضي ناطقة بالألمانية

- مقاطعات إيطاليا