ماني

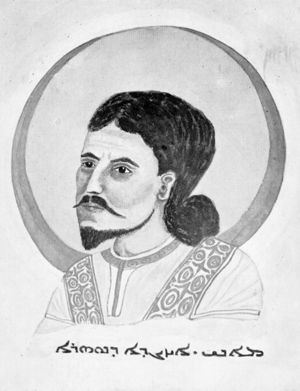

ماني (بالفارسية الوسطى والسريانية Mānī، باليونانية Μάνης، باللاتينية Manes؛ وأيضاً Μανιχαίος، باللاتينية Manichaeus، من السريانية ܡܐܢܝ ܚܝܐ ماني حيا "ماني الحي"، بالإنگليزية: Mani؛ ح. 216–276 م)، من أصل إيراني[1][2][3][4] كان نبياً ومؤسس المانوية، وهي ديانة غنوصية (عرفانية) في القدم المتأخر وقد انتشرت لفترة، إلا أنها الآن قد اندثرت. وُلد ماني في، أو بالقرب من، سلوقيا-قطسيفون في آشورستان (بلاد آشور)، وكانت آنذاك لازالت جزءاً من الامبراطورية الپارثية. وستة من أعماله الرئيسية مكتوبة بالآرامية السريانية والسابع، المكرس لملك الامبراطورية، شاپور الأول، مكتوب بالفارسية الوسطى.[5] وتوفي في گوندشاپور، في الامبراطورية الساسانية.

المصادر

من المصادر الإسلامية القروسطية

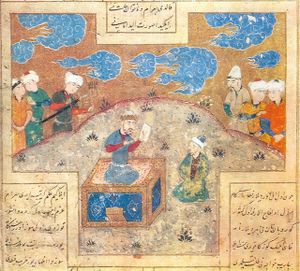

In the medieval Islamic tradition, Mani is described as a painter who set up a sectarian movement in opposition to Zoroastrianism. اضطهد شاپور الأول ماني، ففر إلى تركستان, where he made disciples and embellished with paintings a Tchighil (or picturarum domus Chinensis) and another temple called Ghalbita. Provisioning in advance a cave which had a spring, he told his disciples he was going to heaven, and would not return for a year, after which time they were to seek him in the cave in question. They then and there found him, whereupon he showed them an illustrated book, called Ergenk, or Estenk, which he said he had brought from heaven: whereafter he had many followers, with whom he returned to Persia at the death of Shapur. The new king, Hormisdas, joined and protected the sect; and built Mani a castle. The next king, Bahram or Varanes, at first favoured Mani; but, after getting him to debate with certain Zoroastrian teachers, caused him to be flayed alive, and the skin to be stuffed and hung up. Thereupon most of his followers fled to India, and some even to China, those remaining being reduced to slavery.

In yet another Muslim account we have the details that Mani's mother was named Meis or Utachin, or Mar Marjam (Sancta Maria); and that he was supernaturally born. At the behest of an angel he began his public career, with two companions, at the age of twenty-four, on a Sunday, the first day of Nisan, when the sun was in Aries. He travelled for about forty years; wrote six books, and was raised to Paradise after being slain under Bahram "son of Shapur." Some say he was crucified "in two halves" and so hung up at two gates, afterwards called High-Mani and Low-Mani; others that he was imprisoned by Shapur and freed by Bahram; others that he died in prison. "But he was certainly crucified."[6]

انظر أيضاً

- أغسطين من هيپو

- Mar Ammo

- Codex Manichaicus Coloniensis

- مانوية

- إنجيل ماني

- The Book of Giants

- حدائق الأنوار (رواية)

الهامش

- ^ Boyce, Mary (2001), Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices, Routledge, p. 111, "He was Iranian, of noble Parthian blood..."

- ^ Ball, Warwick (2001), Rome in the East: the transformation of an empire, Routledge, p. 437, "Manichaeism was a syncretic religion, proclaimed by the Iranian Prophet Mani".

- ^ Sundermann, Werner (2009), Mani, the founder of the religion of Manicheism in the 3rd century CE, Sundermann, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism, "According to the Fehrest, Mani was of Arsacid stock on both his father’s and his mother’s sides, at least if the readings al-ḥaskāniya (Mani’s father) and al-asʿāniya (Mani’s mother) are corrected to al-aškāniya and al-ašḡāniya (ed. Flügel, 1862, p. 49, ll. 2 and 3) respectively. The forefathers of Mani’s father are said to have been from Hamadan and so perhaps of Iranian origin (ed. Flügel, 1862, p. 49, 5–6). The Chinese Compendium, which makes the father a local king, maintains that his mother was from the house Jinsajian, explained by Henning as the Armenian Arsacid family of Kamsarakan (Henning, 1943, p. 52, n. 4 = 1977, II, p. 115). Is that fact, or fiction, or both? The historicity of this tradition is assumed by most, but the possibility that Mani’s noble Arsacid background is legendary cannot be ruled out (cf. Scheftelowitz, 1933, pp. 403–4). In any case, it is characteristic that Mani took pride in his origin from time-honored Babel, but never claimed affiliation to the Iranian upper class."

- ^ Bausani, Alessandro (2000), Religion in Iran: from Zoroaster to Baha'ullah, Bibliotheca Persica Press, p. 80, "We are now certain that Mani was of Iranian stock on both his father's and his mother's side".

- ^ Henning, W.B., The Book of Giants, BSOAS, Vol. XI, Part 1, 1943, pp. 52–74: "…Mani, who was brought up and spent most of his life in a province of the Persian empire, and whose mother belonged to a famous Parthian family, did not make any use of the Iranian mythological tradition. There can no longer be any doubt that the Iranian names of Sām, Narīmān, etc., that appear in the Persian and Sogdian versions of the Book of the Giants, did not figure in the original edition, written by Mani in the Syriac language."

- ^ John M. Robertson, Pagan Christs (2nd ed. 1911), § 14. The Problem of Manichæus. Gustav Flügel, Mani, seine Lehre and seine Schriften, 18f 2 (trans. from the Fihrist of Muhammad ben Ishak al Nurrâk, with commentary), pp. 84, 97, 99-100, 102-3.

- Asmussen, Jes Peter, comp., Manichaean Literature: Representative Texts, Chiefly from Middle Persian and Parthian Writings, 1975, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, ISBN 9780820111414.

- Alexander Böhlig, 'Manichäismus' in: Theologische Realenzyklopädie 22 (1992), 25–45.

- Amin Maalouf, The Gardens of Light [Les Jardins de Lumière], translated from French by Dorothy S. Blair, 242 p. (Interlink Publishing Group, New York, 2007). ISBN 1566562481