جامع فرحات پاشا

| جامع فرحات باشا | |

|---|---|

جامع فرحات باشا، في أبريل 1941 | |

| الدين | |

| الارتباط | الإسلام |

| الموقع | |

| الموقع | بانيا لوكا، البوسنة والهرسك |

| الإحداثيات الجغرافية | 44°46′02.69″N 17°11′14.44″E / 44.7674139°N 17.1873444°E |

| العمارة | |

| المعماري | مجهول (تلميذ معمار سنان) |

| النوع المعماري | مسجد |

| اكتمل | 1579 |

| ارتفاع المئذنة | 41, 65 m [1] |

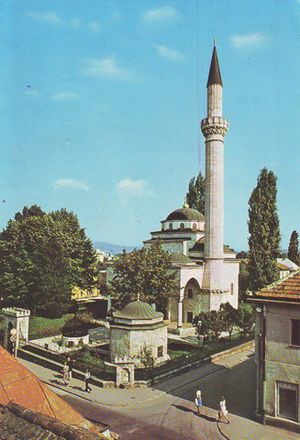

جامع فرحات پاشا (بوسنية: [Ferhat-pašina džamija] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)؛ تركية: Ferhad Paşa Camii)؛ إنگليزية: Ferhat Pasha Mosque؛ ويُعرف أيضاً بإسم مسجد فرهاديا Ferhadija Mosque، كان مبنى مركزياً في مدينة بانيا لوكا وأحد أعظم إنجازات الدولة العثمانية في القرن السادس عشر في البوسنة لنشر العمارة الإسلامية في أوروپا. الجامع دُمـِّر بالكامل في 1993 بأمر من سلطات جمهورية صرب البوسنة وأعيد بناؤه وأفتتح في مايو 2016.

Commissioned by the Bosnian Sanjak-bey Ferhat-paša Sokolović, the mosque was built in 1579[2] with money, as tradition has it,[3] that were paid by the Auersperg family for the severed head of the Habsburg general Herbard VIII von Auersperg and the ransom for the general's son after a battle at the Croatian border in 1575, where Ferhat-paša was triumphant.[4]

The mosque with its classical Ottoman architecture was most probably designed by a pupil of معمار سنان. There is no written data about the builders who erected the mosque, but from analysing its architecture it appears that the foreman of the works was from Sinan's school since the mosque shows obvious similarities with Sinan's Muradiye mosque in مانيسا، which dates from 1585.[5]

الوصف المعماري

يضم مجمع جامع فرحات باشا المسجد الجامع نفسه، والإيوان، المقبرة، نافورة، 3 أضرحة ("تربة") والسور المحيط وبوابته.

تدميره

The mosque was one of 16 destroyed in the city of Banja Luka during the Bosnian War between 1992 and 1995.

The Republika Srpska authorities ordered the demolition of the entire Ferhadija and Arnaudija mosque complexes, which stood approximately 800 m (2،625 ft) apart. Both mosques were destroyed in the same night within 15 minutes of each other. (It has been noted that the almost simultaneous destruction of the Ferhadija and Arnaudija mosques required large quantities of explosives and extensive coordination. Many believe that this would not have been possible without the involvement of Banja Luka and Republika Srpska authorities.)

The Serb militia blew up the Ferhadija Mosque on the night of 6-7 May, 1993. May 6 is the date of the Serbian Othodox holiday of Đurđevdan (Saint George’s day). The minaret survived the first explosion, but was then razed to the ground.[6]

Most of the debris was taken to the city dump; some stone, and ornamental details, were crushed by the Serbs for use as landfill. The leveled site was turned into a parking lot. Several weeks after the destruction of Ferhadija the nearby Sahat Kula, one of the oldest Ottoman clock towers in Europe, was also destroyed.

At the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia a Serb leader from Banja Luka, Radoslav Brđanin, was convicted for his part in organizing the destruction of Muslim property including mosques, and also in the ethnic cleansing of non-Serbs. He was sentenced to a single prison term of 32 years.

The Brđanin case proved that the destruction of the mosques was orchestrated as part of the ethnic cleansing1|2 campaign.[7] In addition, the Bosnian side in the Bosnian genocide case at the International Court of Justice has cited the destruction of Ferhadija Mosque as one of the elements of ethnic cleansing and genocide employed by the RS authorities during the Bosnian War.

إعادة بنائه

In 2001 a building permit was granted to the Islamska Zajednica Banjaluke (Islamic Community of Banja Luka) to reconstruct the mosque. On May 7, Serb nationalists attacked about 300 Bosniaks attending the ceremony to mark the laying of the cornerstone. The New York Times reported that about 1,000 Orthodox Christian Serbs participated in the attack and that they threw rocks and burned vehicles, a bakery, Muslim prayer rugs, and the flag on the Islamic center, where they hoisted the Bosnian Serb flag; drove a pig onto the site of the mosque as an insult to Muslims; and trapped 250 people in the Islamic center including the head of the UN in Bosnia, the ambassadors from Great Britain, Sweden and Pakistan, and other international and local officials. Bosnian Serb police eventually released them. More than 30 Bosniaks were injured and at least eight were taken to the Banja Luka hospital. One died later from head injuries.[8][9] The disrupted ceremony took place on the 8th anniversary of the mosque's destruction, a date subsequently chosen as Bosnia and Herzegovina’s official Day of the Mosques. A few days later, in secret and under heavy security, the ceremony was performed successfully. But because of the earlier attack, reconstruction was not undertaken.

Although most of the mosques destroyed in Banja Luka in the Bosnian War have been reconstructed since 2001, Ferhadija is still a contentious issue. Work was delayed by the complexities involved in rebuilding it authentically. The Sarajevo School of Architecture’s Design and Research Center had prepared preliminary studies, and the cost of reconstruction was estimated at about 12 million KM (around $8 million). A local magistrate ruled that the authorities of Banja Luka, which is Bosnian Serb-controlled, must pay $42 million to its Islamic community for the 16 local mosques (including Ferhadija Mosque) that were destroyed during the 1992-1995 Bosnian War.[10] However, this ruling was subsequently overturned by the highest court in Sarajevo when the Serb Republic objected to paying for the damage caused by individual people.

The site, with its original architectural remains, is listed as a National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina. By Ruling of the Institute for the Protection of the Cultural, Historical and Natural Heritage of Bosnia and Herzegovina the building was placed under state protection and entered in the register of cultural monuments. The Regional Plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina to 2002 listed the Ferhad-paša mosque in Banja Luka as a Category I building under serial no. 38.[11]

In June 2007 repairs were completed on the foundations that survived the destruction, and reconstruction of the masonry is currently well advanced.

الافتتاح، مايو 2016

تدفق الآلاف إلى عاصمة دويلة الصرب في جمهورية البوسنة اليوم (السبت) لحضور إعادة افتتاح «مسجد فرحات باشا» التاريخي الذي دمرته الحرب في مراسم يُنظر إليها على أنها تشجع التسامح الديني بين الطوائف والأعراق المختلفة. وبعد مرور 20 عاماً على الحرب الطاحنة بين البوسنيين المسلمين والصرب الأرثوذكس والكروات الكاثوليك، لا تزال جمهورية البوسنة مقسمة على أسس عرقية وفي مجموعات متنافسة تعرقل الوفاق والإصلاح المطلوبين للانضمام إلى الاتحاد الأوروبي.[12]

وتبث عودة المسلمين إلى المسجد، الذي أُعيد بناؤه في مدينة بانيا لوكا عاصمة جمهورية الصرب شبه المستقلة في البوسنة، أمل التغيير في نفوس الكثيرين.

وتعطي التدابير الأمنية المحيطة بالمراسم التي سيحضرها مسؤولون بوسنيون كبار وكذلك رئيس الوزراء التركي أحمد داود أوغلو، انطباعاً بأن الحدث ينطوي على مخاطر عالية.

وانتشر حوالى ألف من عناصر الشرطة في الشوارع ووصلت حافلات تُقلّ مسلمين قدموا من مختلف أنحاء البلاد. ومُنعت حركة المرور عن وسط المدينة وحُظرت المشروبات الكحولية.

ويرجع تاريخ المسجد إلى القرن الـ16 وهو تحت حماية «منظمة الأمم المتحدة للتربية والعلم والثقافة» (اليونسكو) على اعتباره نموذجاً فريداً لفن العمارة العثمانية. وتعرض المسجد إلى التدمير قبل 23 عاماً وتحول موقعه إلى ساحة لانتظار السيارات.

ويعتقد كثيرون أن تدميره كان بأمر من صرب البوسنة رغبة منهم في محو أي آثار للتراث الإسلامي من المدينة التي كانت يوماً متعددة الأعراق.

وخلال الاحتفال بوضع حجر الأساس لمشروع إعادة بناء المسجد عام 2001، والذي ساهمت تركيا في تمويله، هاجم قوميون من الصرب، الزائرين والشخصيات العامة المشاركة وقتلوا مسلماً وأصابوا العشرات. واستغرق الحصول على تراخيص إعادة بناء المسجد وعلى المال اللازم لها 15 عاماً، فيما استُخدمت آلاف القطع من أنقاض المبنى الأصلي بعد انتشالها من نهر فرباس ومن موقع للنفايات.

واليوم الذي دُمر المسجد فيه، أي في السابع من أيار (مايو)، أصبح "يوم مساجد البوسنة" التي تم تدمير 614 مسجداً فيها إبان الحرب التي دامت من عام 1992 إلى عام 1995.

ولا يعيش في مدينة بانيا لوكا الآن سوى عشرة في المئة فقط من سكانها المسلمين والكروات بعدما شن الصرب حملة تطهير عرقي في أراض أقاموا عليها دويلتهم.

الهوامش والمراجع

الملاحظات

1The ICTY Trial Chamber is satisfied beyond reasonable doubt both that the expulsions and forcible removals were systematic throughout the Autonomous Region of Krajina (ARK), in which and from where tens of thousands of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats were permanently displaced, and that this mass forcible displacement was intended to ensure the ethnic cleansing of the region. These people were left with no option but to escape. Those who were not expelled and did not manage to escape were subjected to intolerable living conditions imposed by the Serb authorities, which made it impossible for them to continue living there and forced them to seek permission to leave. Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats were subjected to movement restrictions, as well as to perilous living conditions; they were required to pledge their loyalty to the Serb authorities and in at least one case, to wear white armbands. They were dismissed from their jobs and stripped of their health insurance. Campaigns of intimidation specifically targeting Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats were undertaken.

2This process of ethnic cleansing was sometimes camouflaged as a process of resettlement of populations. In Banja Luka, the Agency for Population Movement and the Exchange of Material Wealth for the ARK ("Agency"), which was established on 12 June 1992 pursuant to a decision of the ARK Crisis Staff, aided in the implementation of both the exchange of flats and the resettlement of populations. The Agency was popularly known variously as "Perka’s Agency" or as "Brđanin’s Agency". The ICTY Trial Chamber is of the view that although this Agency was set up for the exchange of flats and the resettlement of populations, this was nothing else but an integral part of the ethnic cleansing plan.

الهامش

- ^ Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage, C. A. Brebbia,L. Binda, page 437

- ^ ArchNet Digital Library: Ferhad Pasha Mosque

- ^ János Asbóth (Johann von Asbóth), Bosnien und die Herzegowina: Reisebilder und Studien, Vienna, A. Hölder, 1888, p. 374

- ^ dejaNet.de: Banja Luka

- ^ Džemal Ćelić, Ferhadija u Banjaluci (i.e. “Ferhadija in Banja Luka” ), ed. Society of Conservators of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo 1968, p. 6

- ^ Transition Online

- ^ UN.org: Brdjanin trial

- ^ Bosnian Serb Crowd Beats Muslims at Mosque Rebuilding, New York Times, May 8, 2001

- ^ Perica Vucinic, Republic 0%, World Press Review Vol. 48,10 (October 2001)

- ^ Bosnian Serbs Told To Pay $42Mln For Burnt Mosques, Dalje.com, February 20 2009

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMonument - ^ رويترز (2016-05-07). "إعادة افتتاح مسجد تاريخي في البوسنة". صحيفة الحياة اللبنانية.

انظر أيضاً

وصلات خارجية

- Bosnia and Herzegovina Commission to Preserve National Monuments: Ferhad Pasha mosque (Ferhadija) in Banja Luka,

- "Principles and Methodological Procedure for Reconsolidation of Ferhat-Pasha Mosque in Banja Luka"- School of Architecture - Design and Research Center, Sarajevo

- Ferhadija Case

- HRW report on ethnic cleansing in Banja Luka

- HRW report on riots

- Images from the riot

- Bosnia and Herzegovina Commission to Preserve National Monuments - Ferhadija

- Radoslav Brđanin judgement about ethnic cleansing in Banja Luka

- Rebuilding Ferhadija

- Human Rights in a Multi-Ethnic Bosnia - Harvard study

- Projekat Ferhadija - website documenting the reconstruction of the Ferhadija mosque

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- مساجد البوسنة والهرسك

- عمارة البوسنة والهرسك

- مساجد في البوسنة والهرسك

- Banja Luka

- مباني ومنشآت في جمهورية صرب البوسنة

- مساجد مدمرة

- Attacks on places of worship during the Bosnian War

- مساجد القرن 16

- Ottoman mosques in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Rebuilt buildings and structures in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Destruction of mosques by Christians