النسر (كشعار)

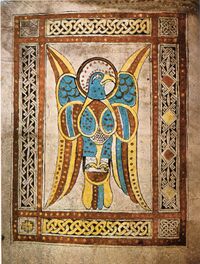

The eagle is used in heraldry as a charge, as a supporter, and as a crest. Heraldic eagles can be found throughout world history like in the Achaemenid Empire or in the present Republic of Indonesia. The European post-classical symbolism of the heraldic eagle is connected with the Roman Empire on one hand (especially in the case of the double-headed eagle), and with Saint John the Evangelist on the other.

التاريخ

A golden eagle was often used on the banner of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. Eagle (or the related royal bird vareghna) symbolized khvarenah (the God-given glory), and the Achaemenid family was associated with eagle (according to legend, Achaemenes was raised by an eagle). The local rulers of Persis in the Seleucid and Parthian eras (3rd-2nd centuries BC) sometimes used an eagle as the finial of their banner. Parthians and Armenians used eagle banners, too.[1]

European heraldry

13th century example (Henry I, Duke of Mödling 1203)

14th century example (Charles IV 1349)

15th century example (Wernigeroder Wappenbuch c. 1480)

التصوير

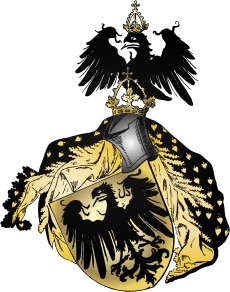

Imperial Eagle

The Aquila was the eagle standard of a Roman legion, carried by a special grade legionary known as an Aquilifer, from the second consulship of Gaius Marius (104 BC) used as the only legionary standard. It was made of silver, or bronze, with outstretched wings. The eagle was not immediately retained as a symbol of the Roman Empire in general in the early medieval period. Neither the early Byzantine emperors nor the Carolingians used the eagle in their coins or seals. It appears that the eagle is only revived as a symbol of Roman imperial power in the high medieval period, being featured on the sceptres of the Ottonians in the late 10th century, and the double-headed eagle gradually appearing association with the Komnenos dynasty in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Holy Roman Empire

The eagle is used as an emblem by the Holy Roman Emperors from at least the time of Otto III (late 10th century), in the form of the "eagle-sceptre".

Byzantine imperial eagle

Eagle of Saint John

Piast and Přemyslid dynasties

Seal of Przemysł II (1295)

Moravian eagle, fresco in the castle Gozzoburg in Krems (c. 1270)

Henry IV Probus, Duke of Silesia with the Silesian eagle in Codex Manesse (c. 1305–1340)

Coat of arms of the King of Poland, after the Grand Armorial équestre de la Toison d'or (c. 1430–1461).

Modern usage

Heraldic eagles

Heraldic eagles are enduring symbols used in the national coats of arms of a number of countries:

- Albania: Principality of Albania (1914), House of Kastrioti coat of arms

- Armenia: Quarterly, eagles for the Artaxiad and Arsacid dynasties (adopted 1992).

- Austria: Reichsadler (1919).

- Czech Republic: Quartered, Moravian and Silesian eagles (Jiří Louda 1992)

- Germany: the German Bundesadler (since 1950), a direct continuation of the Reichsadler design used in the Weimar Republic from 1928.

- Liechtenstein: Coat of arms of Hans-Adam II, Prince of Liechtenstein (و. 1945), with the Silesian eagle in the first quarter.

- Moldova: an eagle displayed holding an Orthodox cross in its beak, adopted 1990.

- Montenegro: Byzantine imperial eagle (2004).

- Poland: Piast dynasty, adopted 1990.

- Romania: Eagles for Wallachia and Transylvania, adopted 2016, partially based on the arms of Carol I of Romania (1881)

- Russia: Byzantine imperial eagle, adopted 1992, first adopted for Muscovy by Ivan III of Russia (1472).

- Serbia: Serbian eagle (Byzantine imperial eagle, Nemanjić dynasty).

Naturalistic eagles

United States

Since 20 June 1782, the United States has used its national bird, the bald eagle, on its Great Seal; the choice was intended to at once recall the Roman Republic and be uniquely American (the bald eagle being indigenous to North America). The representation of the American Eagle is thus a unique combination between a naturalistic depiction of the bird, and the traditional heraldic attitude of the "eagle displayed".

The American Eagle has been a popular emblem throughout the life of the republic, with an eagle appearing in its current form since 1885, in the flags and seals of the President, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, Justice Department, Defense Department, Postal Service, and other organizations, on various coins (such as the quarter-dollar), and in various American corporate logos past and present, such as those of Case and American Eagle Outfitters.

French Empire

The French Imperial Eagle or Aigle de drapeau (lit. "flag eagle") was a figure of an eagle on a staff carried into battle as a standard by the Grande Armée of Napoleon I during the Napoleonic Wars.

Although they were presented with Regimental Colours, the regiments of Napoleon I tended to carry at their head the Imperial Eagle. This was the bronze sculpture of an eagle weighing 1.85 kg (4 lb), mounted on top of the blue regimental flagpole. They were made from six separately cast pieces and, when assembled, measured 310 mm (12 in) in height and 255 mm (10 in) in width. On the base would be the regiment's number or, in the case of the Guard, Garde Impériale. The eagle bore the same significance to French Imperial regiments as the colours did to British regiments - to lose the eagle would bring shame to the regiment, who had pledged to defend it to the death.

Upon Napoleon's fall, the restored monarchy of Louis XVIII of France ordered all eagles to be destroyed and only a very small number escaped. When the former emperor returned to power in 1815 (known as the Hundred Days) he immediately had more eagles produced, although the quality did not match the originals. The workmanship was of a lesser quality and the main distinguishing changes had the new models with closed beaks and they were set in a more crouched posture.

Napoleon also used the French Imperial Eagle in the heraldry of the First Empire, as did his nephew Napoleon III during the Second Empire. An eagle remains in the arms of the House of Bonaparte and the current royal house of Sweden retains the French Imperial Eagle on its dynastic inescutcheon, as his founder, Jean Bernadotte, was a Marshal of France.

Other national emblems

- The coat of arms of Panama (1904), has an eagle rising with wings displayed and elevated on place of a crest. Since 2002 the eagle is officially specified as a harpy eagle.

- The coat of arms of Jordan (1921) featured an eagle before the development of the "Eagle of Saladin" emblem.

- The coat of arms of Iceland (1944) has an eagle or griffin (Gammur) among its supporters.

- The coat of arms of the Philippines (1946) includes the bald eagle of the United States.

- The national emblem of Indonesia (1950) has a Garuda (mythological bird) styled after the Javan hawk-eagle

- The coat of arms of Ghana (1957) has two tawny eagles as supporters.

- Coat of arms of Nigeria (1960)

- The coat of arms of Mexico (1968) shows a Mexican golden eagle devouring a rattle snake.

- The coat of arms of Namibia (1990) has an African fish eagle.

- The flag of Kazakhstan has a soaring steppe eagle.

- The coat of arms of South Sudan (2011) has an African fish eagle.

- The emblem of Kyrgyzstan (2016) has a hawk.

Military badges

Naturalistic eagles are often used in military emblems, such as the emblem of the Royal Air Force (United Kingdom), NATO School, the European Personnel Recovery Centre, etc.

Eagle of Saladin

In Arab nationalism, with the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, the eagle became the symbol of revolutionary Egypt, and was subsequently adopted by several other Arab states (the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Libya, the partially recognised State of Palestine, and Yemen).

The eagle is commonly identified as Saladin's emblem due to his yellow flag was adorned with an eagle,[4] as well as the depiction of an Egyptian vulture on the west wall of the Cairo Citadel which was built during the rule of Saladin.[5] The current design of the eagle itself, however, is of more recent date specifically after the Egyptian revolution of 1952.

As a heraldic symbol identified with Arab nationalism, the Eagle of Saladin was subsequently adopted as the coats of arms of Iraq and Palestine. It has previously been the coat of arms of Libya, but later replaced by the Hawk of Quraish. The Hawk of Quraish was itself abandoned after the Libyan Civil War. The Eagle of Saladin was part of the coat of arms of South Yemen prior to that country's unification with North Yemen.

Zimbabwe Bird

The stone-carved Zimbabwe Bird is the national emblem of Zimbabwe, appearing on the national flags and coats of arms of both Zimbabwe and Rhodesia (since 1924), as well as on banknotes and coins (first on Rhodesian pound and then Rhodesian dollar). It probably represents the bateleur eagle or the African fish eagle.[6][7] The bird's design is derived from a number of soapstone sculptures found in the ruins of the ancient city of Great Zimbabwe.

See also

- Double-headed eagle

- Triple-headed eagle

- Garuda (as a cultural and national symbol)

- Golden eagles in human culture

- Lion (heraldry)

References

Notes

- ^ Depiction of this coat of arms for Wernher von Homberg as participant in the Italian campaign of Henry VII in Codex Balduini due to the similarity with the imperial coat of arms had long been misinterpreted as representing Henry himself. [2]

Citations

- ^ Alireza Shapur Shahbazi (December 15, 1994), "DERAFŠ", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VII, Fasc. 3, pp. 312-315.

- ^ Georg Irmer, Die Romfahrt Kaiser Heinrich's VII im Bildercyclus des Codex Balduini Trevirensis (1881), p. 45.

- ^ Die Wappen der Deutschen Landesfürsten (= J. Siebmachers großes Wappenbuch) vol. 1 part 2-5 (reprint), Nuremberg (1909-1929).

- ^ Hathaway, Jane (2003). A Tale of Two Factions: Myth, Memory, and Identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen. State University of New York Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9780791458839.

- ^ Rabbat, Nasser O. (1995). The Citadel of Cairo: A New Interpretation of Royal Mameluk Architecture. ISBN 9789004101241.

- ^ Thomas N. Huffman (1985). "The Soapstone Birds from Great Zimbabwe". African Arts. 18 (3): 68–73, 99–100. doi:10.2307/3336358. JSTOR 3336358.

- ^ Paul Sinclair (2001). "Review: The Soapstone Birds of Great Zimbabwe Symbols of a Nation by Edward Matenga". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 56 (173/174): 105–106. doi:10.2307/3889033. JSTOR 3889033.

Bibliography

- Clark, Hugh (1892) [1775]. Planché, J. R. (ed.). An Introduction to Heraldry (18th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. ISBN 1-4325-3999-X. LCCN 26005078 – via Internet Archive.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. New York: Dodge Publishing. ISBN 0-517-26643-1. LCCN 09023803 – via Internet Archive.

- Puttock, A.G. (1988). Heraldry in Australia. Frenchs Forest: Child & Associated Publishing.

- von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole, England: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-0940-5. LCCN 81670212.