تشستر آرثر

| تشستر آرثر | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 21 | |

| في المنصب 19 سبتمبر 1881 – 4 مارس، 1885 | |

| نائب الرئيس | لا أحد |

| سبقه | جيمس گارفيلد |

| خلفه | گروڤر كليڤلاند |

| نائب رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 20 | |

| في المنصب 4 مارس, 1881 – 19 سبتمبر, 1881 | |

| الرئيس | جيمس گارفيلد |

| سبقه | وليام هويلر |

| خلفه | توماس هندريكس |

| 21st Collector of the Port of New York | |

| في المنصب 1871–1878 | |

| عيـّنه | Ulysses S. Grant |

| سبقه | Thomas Murphy |

| خلفه | Edwin Atkins Merritt |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | أكتوبر 5, 1829 فيرفيلد، ڤرمونت |

| توفي | نوفمبر 18, 1886 (aged 57) نيويورك, نيويورك |

| القومية | أمريكي |

| الحزب | جمهوري |

| انتماءات سياسية أخرى |

Whig (Before 1856) |

| الجامعة الأم | |

| المهنة | محامي, موظف عمومي، مربي (مدرس) |

| المهنة |

|

| الدين | Episcopal |

| التوقيع | |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الولاء |

|

| الخدمة/الفرع | جيش الاتحاد |

| الرتبة | |

| الوحدة | New York Guard |

| المعارك/الحروب | الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية |

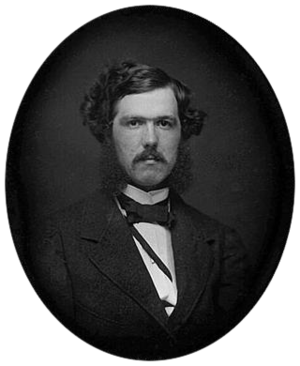

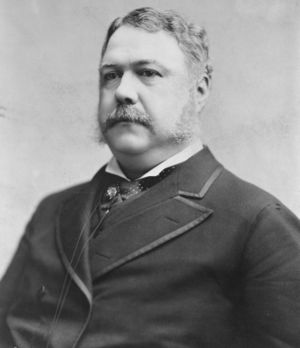

تشستر ألن آرثر Chester Alan Arthur (عاش 5 أكتوبر 1829 - 18 نوفمبر 1886) الرئيس الأمريكي الحادي والعشرون وقد تولى الحكم لفترة ولاية واحدة بين عام 1881-1885. Previously the 20th vice president, he succeeded to the presidency upon the death of President James A. Garfield in September 1881, two months after Garfield was shot by an assassin.

Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont, grew up in upstate New York and practiced law in New York City. He served as quartermaster general of the New York Militia during the American Civil War. Following the war, he devoted more time to New York Republican politics and quickly rose in Senator Roscoe Conkling's political organization. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him to the post of Collector of the Port of New York in 1871, and he was an important supporter of Conkling and the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes fired Arthur as part of a plan to reform the federal patronage system in New York. When U.S Representative James Garfield won the Republican nomination for president in 1880, Arthur was nominated for vice president to balance the successful ticket as an Eastern Stalwart. Four months into his term, an assassin shot Garfield, who died 11 weeks later. Arthur then assumed the presidency.

At the outset, Arthur struggled to overcome a negative reputation as a Stalwart and product of Conkling's organization. To the surprise of reformers, he advocated and enforced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. He presided over the rebirth of the US Navy, but he was criticized for failing to alleviate the federal budget surplus which had been accumulating since the end of the Civil War. Arthur vetoed the first version of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, arguing that its twenty-year ban on Chinese immigrants to the United States violated the Burlingame Treaty, but he signed a second version, which included a ten-year ban.[1]

Suffering from poor health, Arthur made only a limited effort to secure the Republican Party's nomination in 1884, and he retired at the end of his term. Journalist Alexander McClure wrote, "No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted as Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired ... more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe."[2] Arthur's failing health and political temperament combined to make his administration less active than a modern presidency, yet he earned praise among contemporaries for his solid performance in office. The New York World summed up Arthur's presidency at his death in 1886: "No duty was neglected in his administration, and no adventurous project alarmed the nation."[3] Mark Twain wrote of him, "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration."[4] Despite this, modern historians generally rank Arthur as a mediocre president, as well as the least memorable.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

النشأة

مطلع حياته العملية

محامي بنيويورك

الحرب الأهلية

In 1861, Arthur was appointed to the military staff of Governor Edwin D. Morgan as engineer-in-chief.[5] The office was a patronage appointment of minor importance until the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, when New York and the other northern states were faced with raising and equipping armies of a size never before seen in American history.[6] Arthur was commissioned as a brigadier general and assigned to the state militia's quartermaster department.[6] He was so efficient at housing and outfitting the troops that poured into New York City that he was promoted to inspector general of the state militia in March 1862, and then to quartermaster general that July.[7] He had an opportunity to serve at the front when the 9th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment elected him commander with the rank of colonel early in the war, but at Governor Morgan's request, he turned it down to remain at his post in New York.[8] He also turned down command of four New York City regiments organized as the Metropolitan Brigade, again at Morgan's request.[8] The closest Arthur came to the front was when he traveled south to inspect New York troops near Fredericksburg, Virginia, in May 1862, shortly after forces under Major General Irvin McDowell seized the town during the Peninsula Campaign.[9] That summer, he and other representatives of northern governors met with Secretary of State William H. Seward in New York to coordinate the raising of additional troops, and spent the next few months enlisting New York's quota of 120,000 men.[9] Arthur received plaudits for his work, but his post was a political appointment, and he was relieved of his militia duties in January 1863 when Governor Horatio Seymour, a Democrat, took office.[10] When Reuben Fenton won the 1864 election for governor, Arthur requested reappointment; Fenton and Arthur were from different factions of the Republican Party, and Fenton had already committed to appointing another candidate, so Arthur did not return to military service.[11]

Arthur returned to being a lawyer, and with the help of additional contacts made in the military, he and the firm of Arthur & Gardiner flourished.[12] Even as his professional life improved, however, Arthur and his wife experienced a personal tragedy as their only child, William, died suddenly that year at the age of two.[13] The couple took their son's death hard, and when they had another son, Chester Alan Jr., in 1864, they lavished attention on him.[14] They also had a daughter, Ellen, in 1871. Both children survived to adulthood.[15]

Arthur's political prospects improved along with his law practice when his patron, ex-Governor Morgan, was elected to the United States Senate.[16] He was hired by Thomas Murphy, a Republican politician, but also a friend of William M. Tweed, the boss of the Tammany Hall Democratic organization. Murphy was also a hatter who sold goods to the Union Army, and Arthur represented him in Washington. The two became associates within New York Republican party circles, eventually rising in the ranks of the conservative branch of the party dominated by Thurlow Weed.[16] In the presidential election of 1864, Arthur and Murphy raised funds from Republicans in New York, and they attended the second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln in 1865.[17]

سياسي نيويورك

Conkling's machine

الصدام مع هيز

انتخابات 1880

نيابة الرئيس (1881)

After the election, Arthur worked in vain to persuade Garfield to fill certain positions with his fellow New York Stalwarts—especially that of the Secretary of the Treasury; the Stalwart machine received a further rebuke when Garfield appointed Blaine, Conkling's arch-enemy, as Secretary of State.[18] The running mates, never close, detached as Garfield continued to freeze out the Stalwarts from his patronage. Arthur's status in the administration diminished when, a month before inauguration day, he gave a speech before reporters suggesting the election in Indiana, a swing state, had been won by Republicans through illegal machinations.[19] Garfield ultimately appointed a Stalwart, Thomas Lemuel James, to be Postmaster General, but the cabinet fight and Arthur's ill-considered speech left the President and Vice President clearly estranged when they took office on March 4, 1881.[20]

The Senate in the 47th United States Congress was divided among 37 Republicans, 37 Democrats, one independent (David Davis) who caucused with the Democrats, one Readjuster (William Mahone), and four vacancies.[21] Immediately, the Democrats attempted to organize the Senate, knowing that the vacancies would soon be filled by Republicans.[21] As vice president, Arthur cast tie-breaking votes in favor of the Republicans when Mahone opted to join their caucus.[21] Even so, the Senate remained deadlocked for two months over Garfield's nominations because of Conkling's opposition to some of them.[22] Just before going into recess in May 1881, the situation became more complicated when Conkling and the other Senator from New York, Thomas C. Platt, resigned in protest of Garfield's continuing opposition to their faction.[23]

With the Senate in recess, Arthur had no duties in Washington and returned to New York City.[24] Once there, he traveled with Conkling to Albany, where the former Senator hoped for a quick re-election to the Senate, and with it, a defeat for the Garfield administration.[24][أ] The Republican majority in the state legislature was divided on the question, to Conkling and Platt's surprise, and an intense campaign in the statehouse ensued.[24][ب]

While in Albany on July 2, Arthur learned that Garfield had been shot.[24] The assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, was a deranged office-seeker who believed that Garfield's successor would appoint him to a patronage job. He proclaimed to onlookers: "I am a Stalwart, and Arthur will be President!"[25] Guiteau was found to be mentally unstable, and despite his claims to be a Stalwart supporter of Arthur, they had only a tenuous connection that dated from the 1880 campaign.[26] Twenty-nine days before his execution for shooting Garfield, Guiteau composed a lengthy, unpublished poem claiming that Arthur knew the assassination had saved "our land [the United States]". Guiteau's poem also states he had (incorrectly) presumed that Arthur would pardon him for the assassination.[27]

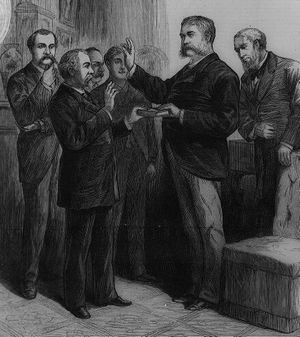

More troubling was the lack of legal guidance on presidential succession: as Garfield lingered near death, no one was sure who, if anyone, could exercise presidential authority.[28] Also, after Conkling's resignation, the Senate had adjourned without electing a president pro tempore, who would normally follow Arthur in the succession.[28] Arthur was reluctant to be seen acting as president while Garfield lived, and for the next two months there was a void of authority in the executive office, with Garfield too weak to carry out his duties, and Arthur reluctant to assume them.[29] Through the summer, Arthur refused to travel to Washington and was at his home on Lexington Avenue in New York City when, on the night of September 19, he learned that Garfield had died in Long Branch, New Jersey.[29] Judge John R. Brady of the New York Supreme Court administered the oath of office in Arthur's home at 2:15 a.m. on September 20. Later that day Arthur took a train to Long Branch to pay his respects to Garfield and to leave a card of sympathy for Mrs. Garfield, afterwards returning to New York. On September 21, he returned to Long Branch to take part in Garfield's funeral, and then joined the funeral train to Washington.[30] Before leaving New York, Arthur ensured the presidential line of succession by preparing and mailing to the White House a proclamation calling for a Senate special session. This step ensured that the Senate had legal authority to convene immediately and choose a Senate president pro tempore, who would be able to assume the presidency if Arthur died. Once in Washington he destroyed the mailed proclamation and issued a formal call for a special session.[31]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الرئاسة (1881–1885)

تولي المنصب

Arthur arrived in Washington, D.C. on September 21.[32] On September 22, he re-took the oath of office, this time before Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite. Arthur took this step to ensure procedural compliance; there had been a lingering question about whether a state court judge (Brady) could administer a federal oath of office.[33][ت] He initially took up residence at the home of Senator John P. Jones, while a White House remodeling he had ordered was carried out, including addition of an elaborate fifty-foot glass screen by Louis Comfort Tiffany.[34]

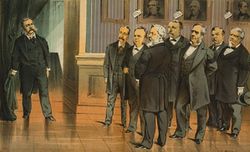

In an 1881 Puck cartoon, Arthur faces the presidential cabinet after President Garfield was shot.

اصلاح الخدمة المدنية

الفائض والتعريفة الجمركية

With high revenue held over from wartime taxes, the federal government had collected more than it spent since 1866; by 1882 the surplus reached $145 million.[35] Opinions varied on how to balance the budget; the Democrats wished to lower tariffs, in order to reduce revenues and the cost of imported goods, while Republicans believed that high tariffs ensured high wages in manufacturing and mining. They preferred the government spend more on internal improvements and reduce excise taxes.[35] Arthur agreed with his party, and in 1882 called for the abolition of excise taxes on everything except liquor, as well as a simplification of the complex tariff structure.[36] In May of that year, Representative William D. Kelley of Pennsylvania introduced a bill to establish a tariff commission;[36] the bill passed and Arthur signed it into law but appointed mostly protectionists to the committee. Republicans were pleased with the committee's make-up but were surprised when, in December 1882, they submitted a report to Congress calling for tariff cuts averaging between 20 and 25%. The commission's recommendations were ignored, however, as the House Ways and Means Committee, dominated by protectionists, provided a 10% reduction.[36] After conference with the Senate, the bill that emerged only reduced tariffs by an average of 1.47%. The bill passed both houses narrowly on March 3, 1883, the last full day of the 47th Congress; Arthur signed the measure into law, with no effect on the surplus.[37]

Congress attempted to balance the budget from the other side of the ledger, with increased spending on the 1882 Rivers and Harbors Act in the unprecedented amount of $19 million.[38] While Arthur was not opposed to internal improvements, the scale of the bill disturbed him, as did its narrow focus on "particular localities," rather than projects that benefited a larger part of the nation.[38] On August 1, 1882, Arthur vetoed the bill to widespread popular acclaim;[38] in his veto message, his principal objection was that it appropriated funds for purposes "not for the common defense or general welfare, and which do not promote commerce among the States."[39] Congress overrode his veto the next day[38] and the new law reduced the surplus by $19 million.[40] Republicans considered the law a success at the time, but later concluded that it contributed to their loss of seats in the elections of 1882.[41]

الشؤون الخارجية والهجرة

During the Garfield administration, Secretary of State James G. Blaine attempted to invigorate United States diplomacy in Latin America, urging reciprocal trade agreements and offering to mediate disputes among the Latin American nations.[42] Blaine, venturing a greater involvement in affairs south of the Rio Grande, proposed a Pan-American conference in 1882 to discuss trade and an end to the War of the Pacific being fought by Bolivia, Chile, and Peru.[42] Blaine did not remain in office long enough to see the effort through, and when Frederick T. Frelinghuysen replaced him at the end of 1881, the conference efforts lapsed.[43] Frelinghuysen also discontinued Blaine's peace efforts in the War of the Pacific, fearing that the United States might be drawn into the conflict.[43] Arthur and Frelinghuysen continued Blaine's efforts to encourage trade among the nations of the Western Hemisphere; a treaty with Mexico providing for reciprocal tariff reductions was signed in 1882 and approved by the Senate in 1884.[44] Legislation required to bring the treaty into force failed in the House, however, rendering it a dead letter.[44] Similar efforts at reciprocal trade treaties with Santo Domingo and Spain's American colonies were defeated by February 1885, and an existing reciprocity treaty with the Kingdom of Hawaii was allowed to lapse.[45]

The 47th Congress spent a great deal of time on immigration, and at times was in accord with Arthur.[46] In July 1882 Congress easily passed a bill regulating steamships that carried immigrants to the United States.[46] To their surprise, Arthur vetoed it and requested revisions, which they made and Arthur then approved.[46] He also signed in August of that year the Immigration Act of 1882, which levied a 50-cent tax on immigrants to the United States, and excluded from entry the mentally ill, the intellectually disabled, criminals, or any other person potentially dependent upon public assistance.[47]

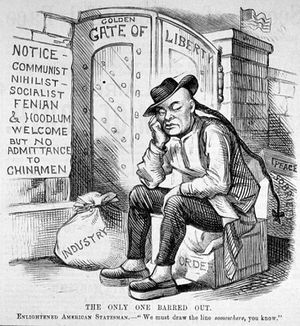

A more contentious debate materialized over the status of Chinese immigrants; in January 1868, the Senate had ratified the Burlingame Treaty with China, allowing an unrestricted flow of Chinese into the country. As the economy soured after the Panic of 1873, Chinese immigrants were blamed for depressing workmen's wages; in reaction Congress in 1879 attempted to abrogate the 1868 treaty by passing the Chinese Exclusion Act, but President Hayes vetoed it.[48] Three years later, after China had agreed to treaty revisions, Congress tried again to exclude working class Chinese laborers; Senator John F. Miller of California introduced another Chinese Exclusion Act that blocked entry of Chinese laborers for a twenty-year period.[49] The bill passed the Senate and House by overwhelming margins, but this as well was vetoed by Arthur, who concluded the 20-year ban to be a breach of the renegotiated treaty of 1880. That treaty allowed only a "reasonable" suspension of immigration. Eastern newspapers praised the veto, while it was condemned in the Western states. Congress was unable to override the veto, but passed a new bill reducing the immigration ban to ten years. Although he still objected to this denial of entry to Chinese laborers, Arthur acceded to the compromise measure, signing the Chinese Exclusion Act into law on May 6, 1882.[49][50] The Chinese Exclusion Act attempted to stop all Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years, with exceptions for diplomats, teachers, students, merchants, and travelers. It was widely evaded.[51][ث]

اصلاح البحرية

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete.[52] The nation's military focus over the fifteen years before Garfield and Arthur's election had been on the Indian wars in the West, rather than the high seas, but as the region was increasingly pacified, many in Congress grew concerned at the poor state of the Navy.[53] Garfield's Secretary of the Navy, William H. Hunt advocated reform of the Navy and his successor, William E. Chandler appointed an advisory board to prepare a report on modernization.[54] Based on the suggestions in the report, Congress appropriated funds for the construction of three steel protected cruisers (Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago) and an armed dispatch-steamer (Dolphin), collectively known as the ABCD Ships or the Squadron of Evolution.[55] Congress also approved funds to rebuild four monitors (Puritan, Amphitrite, Monadnock, and Terror), which had lain uncompleted since 1877.[55] The contracts to build the ABCD ships were all awarded to the low bidder, John Roach & Sons of Chester, Pennsylvania,[56] even though Roach once employed Secretary Chandler as a lobbyist.[56] Democrats turned against the "New Navy" projects and, when they won control of the 48th Congress, refused to appropriate funds for seven more steel warships.[56] Even without the additional ships, the state of the Navy improved when, after several construction delays, the last of the new ships entered service in 1889.[57]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحقوق المدنية

صحته وسفره واعادة ترشيحه

الادارة والحكومة

| حكومة آرثر | ||

|---|---|---|

| المنصب | الاسم | الفترة |

| الرئيس | تشستر آرثر | 1881 – 1885 |

| نائب الرئيس | None | 1881 – 1885 |

| وزير الخارجية | James G. Blaine | 1881 |

| Frederick T. Frelinghuysen | 1881 – 1885 | |

| وزير الخزانة | William Windom | 1881 |

| Charles J. Folger | 1881 – 1884 | |

| Walter Q. Gresham | 1884 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1884 – 1885 | |

| وزير الحربية | Robert T. Lincoln | 1881 – 1885 |

| المدعي العام | Wayne MacVeagh | 1881 |

| Benjamin H. Brewster | 1881 – 1885 | |

| المدير العام لمصلحة البريد | Thomas L. James | 1881 |

| Timothy O. Howe | 1881 – 1883 | |

| Walter Q. Gresham | 1883 – 1884 | |

| Frank Hatton | 1884 – 1885 | |

| وزير البحرية | William H. Hunt | 1881 – 1882 |

| William E. Chandler | 1882 – 1885 | |

| وزير الداخلية | Samuel J. Kirkwood | 1881 – 1882 |

| Henry M. Teller | 1882 – 1885 | |

التقاعد والوفاة والتخليد

انظر أيضاً

- قائمة رؤساء الولايات المتحدة

- List of presidents of the United States by previous experience

- Arthur Cottage, ancestral home, Cullybackey, مقاطعة أنتريم، أيرلندا الشمالية

- جوليا ساند

ملاحظات

- ^ Before the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Senators were elected by state legislatures.

- ^ Conkling and Pratt were ultimately denied re-election, being succeeded by Elbridge G. Lapham and Warner Miller, respectively.

- ^ One presidential oath was administered by a state court judge, also in New York City by a New York State judge: Robert Livingston, Chancellor of New York, administered the first presidential oath to George Washington at Federal Hall in 1789 (there were yet no federal judges). The only other presidential oath administered by someone other than a Federal justice or judge, the first swearing in of Calvin Coolidge in 1923 (by his father John Calvin Coolidge, Sr., a justice of the peace and notary public, in the family home), was also re-taken in Washington due to questions about the validity of the first oath. This second oath taking was done in secret, and did not become public knowledge until Harry M. Daugherty revealed it in 1932.

- ^ The portion of the law denying citizenship to Chinese-American children born in the United States was later found unconstitutional in United States v. Wong Kim Ark in 1898.

الهامش

- ^ Sturgis, Amy H. (2003). Presidents from Hayes Through McKinley. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-3133-1712-5.

- ^ Alexander K. McClure, Colonel Alexander K. McClure's recollections of Half a Century (1902) p 115 online

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 423.

- ^ Feldman, p. 95.

- ^ Howe, pp. 18–19.

- ^ أ ب Howe, pp. 20–21; Reeves 1975, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 24–25.

- ^ أ ب Howe, p. 25.

- ^ أ ب Howe, pp. 26–27; Reeves 1975, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 30.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 33.

- ^ Howe, pp. 30–31; Reeves 1975, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Howe, pp. 29–30; Reeves 1975, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 35.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 84.

- ^ أ ب Reeves 1975, p. 37.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 38.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 205–207.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 213–216; Karabell, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 216–219; Karabell, pp. 54–56.

- ^ أ ب ت Reeves 1975, pp. 220–223.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 223–230.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 230–233.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Reeves 1975, pp. 233–237; Howe, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Karabell, p. 59; Reeves 1975, p. 237.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 238–241; Doenecke, pp. 53–54.

- ^ "Charles Guiteau's reasons for assassinating President Garfield, 1882 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ أ ب Reeves 1975, pp. 241–243; Howe, pp. 152–154.

- ^ أ ب Reeves 1975, pp. 244–248; Karabell, pp. 61–63.

- ^ McCabe.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 247–248.

- ^ The New York Times 1881.

- ^ Doenecke, pp. 53–54; Reeves 1975, p. 248.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 252–253, 268–269.

- ^ أ ب Reeves 1975, pp. 328–329; Doenecke, p. 168.

- ^ أ ب ت Reeves 1975, pp. 330–333; Doenecke, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 334–335.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Reeves 1975, pp. 280–282; Doenecke, p. 81.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 281.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKim-Dwor - ^ Howe, pp. 196–197; Reeves 1975, pp. 281–282; Karabell, p. 90.

- ^ أ ب Doenecke, pp. 55–57; Reeves 1975, pp. 284–289.

- ^ أ ب Doenecke, pp. 129–132; Reeves 1975, pp. 289–293; Bastert, pp. 653–671.

- ^ أ ب Doenecke, pp. 173–175; Reeves 1975, pp. 398–399, 409.

- ^ Doenecke, pp. 175–178; Reeves 1975, pp. 398–399, 407–410.

- ^ أ ب ت Howe, pp. 168–169; Doenecke, p. 81.

- ^ Hutchinson, p. 162; Howe, p. 169.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 277–278; Hoogenboom, pp. 387–389.

- ^ أ ب Reeves 1975, pp. 278–279; Doenecke, pp. 81–84.

- ^ David L. Anderson (1978). "The Diplomacy of Discrimination: Chinese Exclusion, 1876–1882". California History. 57 (1): 32–45. doi:10.2307/25157814. JSTOR 25157814.

- ^ Erika Lee (2003). At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 337; Doenecke, p. 145.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 338–341; Doenecke, pp. 145–147.

- ^ Doenecke, pp. 147–149.

- ^ أ ب Reeves 1975, pp. 342–343; Abbot 1896, pp. 346–347.

- ^ أ ب ت Reeves 1975, pp. 343–345; Doenecke, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 349–350; Doenecke, pp. 152–153.

وصلات خارجية

- Extensive essay on Chester Arthur and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- تشستر آرثر at the دليل سـِيَر الكونگرس الأمريكي

- White House Biography

- Presidential Biography by Appleton's and Stanley L. Klos

- أعمال من Chester Alan Arthur في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- First State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- Second State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- Third State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- Fourth State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- POTUS - Chester Alan Arthur

- Medical and Health history of Chester A. Arthur

- Chester A. Arthur Society

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه وليام ويلر |

Vice President of the United States March 4, 1881 - September 19, 1881 |

تبعه Thomas A. Hendricks |

| سبقه جيمس گارفيلد |

رئيس الولايات المتحدة September 19, 1881 - March 4, 1885 |

تبعه گروڤر كليڤلاند |

| مناصب حزبية | ||

| سبقه وليام ويلر |

Republican Party vice presidential candidate 1880 |

تبعه John A. Logan |

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- رؤساء الولايات المتحدة

- مواليد 1829

- وفيات 1886

- Union College (New York) alumni

- Union Army generals

- Deaths by stroke

- أسقفيون أمريكان

- People from Vermont

- Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- Scots-Irish Americans

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- أمريكان من أصل إنگليزي

- أمريكان من أصل اسكتلندي-أيرلندي

- أمريكان من أصل ويلزي

- Vice Presidents of the United States

- Fairfield, Vermont

- People of Vermont in the American Civil War

- تاريخ الولايات المتحدة (1865–1918)

- Garfield administration cabinet members

- Burials at Albany Rural Cemetery

- جمهوريو نيويورك