أندرو جونسون

| أندرو جونسون | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 17 | |

| في المنصب April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869 | |

| نائب الرئيس | لا أحد |

| سبقه | ابراهام لنكولن |

| خلفه | يوليسيس گرانت |

| 16th Vice President of the United States | |

| في المنصب March 4, 1865 – April 15, 1865 | |

| الرئيس | ابراهام لنكولن |

| سبقه | Hannibal Hamlin |

| خلفه | Schuyler Colfax |

| Military Governor of Tennessee | |

| في المنصب March 12, 1862 – March 4, 1865 | |

| عيـّنه | ابراهام لنكولن |

| سبقه | Isham G. Harris |

| خلفه | E. H. East (Acting) |

| سناتور الولايات المتحدة عن تنسي | |

| في المنصب October 8, 1857 – March 4, 1862 March 4, 1875 – July 31, 1875 | |

| سبقه | James C. Jones William G. Brownlow |

| خلفه | David T. Patterson David M. Key |

| 17th حاكم تنسي | |

| في المنصب October 17, 1853 – November 3, 1857 | |

| سبقه | William B. Campbell |

| خلفه | Isham G. Harris |

| عضو U.S. House of Representatives from تنسي's 1st district | |

| في المنصب March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1853 | |

| سبقه | Thomas D. Arnold |

| خلفه | Brookins Campbell |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | ديسمبر 29, 1808 Raleigh, North Carolina |

| توفي | يوليو 31, 1875 (aged 66) Elizabethton, Tennessee |

| القومية | American |

| الحزب | Democratic National Union Independent |

| المهنة | Tailor |

| الدين | Christian with no denominational affiliation[1][2] |

| التوقيع | |

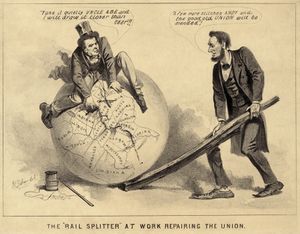

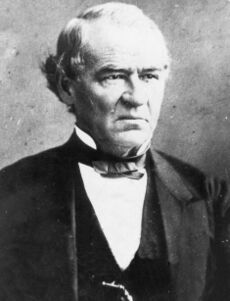

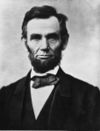

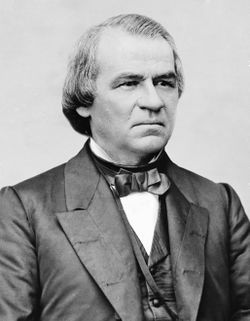

أندرو جونسون (29 ديسمبر 1808 - 31 يوليو 1875)، الرئيس السابع عشر للولايات المتحدة الأمريكية بالفترة من 15 أبريل 1865 إلى 4 مارس 1869.

رئيس الولايات المتحدة من 1865 – 1869م. ديمقراطي، انتُخب نائبًا للرئيس عام 1864م في قائمة الحزب الاتحادي الوطني التي شملت الرئيس أبراهام لنكولن الجمهوري. أصبح جونسون رئيسًا في 15 أبريل 1865م، بعد اغتيال لنكولن.

كان جونسون الرئيس الأمريكي الوحيد الذي اتهم رسميًا بالتقصير وسوء الإدارة من مجلس النواب الأمريكي. نشأ اتهامه أساسًا بسبب اختلافه مع الكونجرس على كيفية معاملة الجنوب بعد الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية من 1861 – 1865م. في مايو 1865م، منح جونسون العفو العام لكل الجنوبيين الذين انطبقت عليهم شروط خاصة.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

نائب الرئيس (1865)

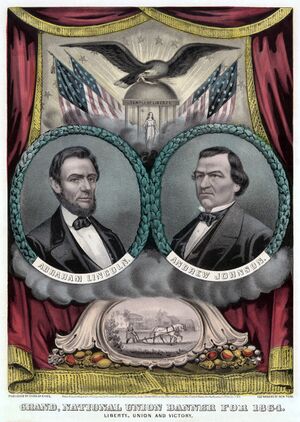

In 1860, Lincoln's running mate had been Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine. Although Hamlin had served competently, was in good health, and was willing to run again, Johnson emerged as running mate for Lincoln's reelection bid in 1864.[3]

Lincoln considered several War Democrats for the ticket in 1864, and sent an agent to sound out General Benjamin Butler as a possible running mate. In May 1864, the president dispatched General Daniel Sickles to Nashville on a fact-finding mission. Although Sickles denied that he was there either to investigate or interview the military governor, Johnson biographer Hans L. Trefousse believes that Sickles's trip was connected to Johnson's subsequent nomination for vice president.[3] According to historian Albert Castel in his account of Johnson's presidency, Lincoln was impressed by Johnson's administration of Tennessee.[4] Gordon-Reed points out that while the Lincoln-Hamlin ticket might have been considered geographically balanced in 1860, "having Johnson, the southern War Democrat, on the ticket sent the right message about the folly of secession and the continuing capacity for union within the country."[5] Another factor was the desire of Secretary of State William Seward to frustrate the vice-presidential candidacy of fellow New Yorker and former senator Daniel S. Dickinson, a War Democrat, as Seward would probably have had to yield his place if another New Yorker became vice president. Johnson, once he was told by reporters the likely purpose of Sickles' visit, was active on his own behalf, delivering speeches and having his political friends work behind the scenes to boost his candidacy.[6]

To sound a theme of unity in 1864, Lincoln ran under the banner of the National Union Party, rather than that of the Republicans.[5] At the party's convention in Baltimore in June, Lincoln was easily nominated, although there had been some talk of replacing him with a cabinet officer or one of the more successful generals. After the convention backed Lincoln, former Secretary of War Simon Cameron offered a resolution to nominate Hamlin, but it was defeated. Johnson was nominated for vice president by C.M. Allen of Indiana with an Iowa delegate seconding it. On the first ballot, Johnson led with 200 votes to 150 for Hamlin and 108 for Dickinson. On the second ballot, Kentucky switched its vote for Johnson, beginning a stampede. Johnson was named on the second ballot with 491 votes to Hamlin's 17 and eight for Dickinson; the nomination was made unanimous. Lincoln expressed pleasure at the result, "Andy Johnson, I think, is a good man."[7] When word reached Nashville, a crowd assembled and the military governor obliged with a speech contending his selection as a Southerner meant that the rebel states had not actually left the Union.[7]

Although it was unusual at the time for a national candidate to actively campaign, Johnson gave a number of speeches in Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana. He also sought to boost his chances in Tennessee while reestablishing civil government by making the loyalty oath even more restrictive, in that voters would now have to swear that they opposed making a settlement with the Confederacy. The Democratic candidate for president, George McClellan, hoped to avoid additional bloodshed by negotiation, and so the stricter loyalty oath effectively disenfranchised his supporters. Lincoln declined to override Johnson, and their ticket took the state by 25,000 votes. Congress refused to count Tennessee's electoral votes, but Lincoln and Johnson did not need them, having won in most states that had voted, and easily secured the election.[8]

Now Vice President-elect, Johnson was eager to complete the work of reestablishing civilian government in Tennessee, although the timetable for the election of a new governor did not allow it to take place until after Inauguration Day, March 4. He hoped to remain in Nashville to complete his task, but was told by Lincoln's advisers that he could not stay, but would be sworn in with Lincoln. In these months, Union troops finished the retaking of eastern Tennessee, including Greeneville. Just before his departure, the voters of Tennessee ratified a new constitution, which abolished slavery, on February 22, 1865. One of Johnson's final acts as military governor was to certify the results.[9]

Johnson traveled to Washington to be sworn into office, although according to Gordon-Reed, "in light of what happened on March 4, 1865, it might have been better if Johnson had stayed in Nashville."[10] Johnson may have been ill; Castel cited typhoid fever,[4] though Gordon-Reed notes that there is no independent evidence for that diagnosis.[10] On the evening of March 3, Johnson attended a party in his honor at which he drank heavily. Hung over the following morning at the Capitol, he asked Vice President Hamlin for some whiskey. Hamlin produced a bottle, and Johnson took two stiff drinks, stating "I need all the strength for the occasion I can have." In the Senate Chamber, Johnson delivered a rambling address as Lincoln, the Congress, and dignitaries looked on. Almost incoherent at times, he finally meandered to a halt, whereupon Hamlin hastily swore him in as vice president.[11] Lincoln, who had watched sadly during the debacle, then went to his own swearing-in outside the Capitol, and delivered his acclaimed Second Inaugural Address.[12]

In the weeks after the inauguration, Johnson only presided over the Senate briefly, and hid from public ridicule at the Maryland home of a friend, Francis Preston Blair. When he did return to Washington, it was with the intent of leaving for Tennessee to reestablish his family in Greeneville. Instead, he remained after word came that General Ulysses S. Grant had captured the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, presaging the end of the war.[13] Lincoln stated, in response to criticism of Johnson's behavior, that "I have known Andy Johnson for many years; he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared; Andy ain't a drunkard."[14]

الرئاسة (1865–1869)

تولي الرئاسة

On the afternoon of April 14, 1865, Lincoln and Johnson met for the first time since the inauguration. Trefousse states that Johnson wanted to "induce Lincoln not to be too lenient with traitors"; Gordon-Reed agrees.[15][16]

That night, President Lincoln was shot and mortally wounded at Ford's Theatre by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer. The shooting of the President was part of a conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln, Johnson, and Seward the same night. Seward barely survived his wounds, while Johnson escaped attack as his would-be assassin, George Atzerodt, got drunk instead of killing the vice president. Leonard J. Farwell, a fellow boarder at the Kirkwood House, awoke Johnson with news of Lincoln's shooting. Johnson rushed to the President's deathbed, where he remained a short time, on his return promising, "They shall suffer for this. They shall suffer for this."[17] Lincoln died at 7:22 am the next morning; Johnson's swearing-in occurred between 10 and 11 am with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding in the presence of most of the Cabinet. Johnson's demeanor was described by the newspapers as "solemn and dignified".[18] Some Cabinet members had last seen Johnson, apparently drunk, at the inauguration.[19] At noon, Johnson conducted his first Cabinet meeting in the Treasury Secretary's office, and asked all members to remain in their positions.[20]

The events of the assassination resulted in speculation, then and subsequently, concerning Johnson and what the conspirators might have intended for him. In the vain hope of having his life spared after his capture, Atzerodt spoke much about the conspiracy, but did not say anything to indicate that the plotted assassination of Johnson was merely a ruse. Conspiracy theorists point to the fact that on the day of the assassination, Booth came to the Kirkwood House and left one of his cards with Johnson's private secretary, William A. Browning. The message on it was: "Don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth."[21]

Johnson presided with dignity over Lincoln's funeral ceremonies in Washington, before his predecessor's body was sent home to Springfield, Illinois, for interment.[22] Shortly after Lincoln's death, Union General William T. Sherman reported he had, without consulting Washington, reached an armistice agreement with Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston for the surrender of Confederate forces in North Carolina in exchange for the existing state government remaining in power, with private property rights (slaves) to be respected. This did not even grant freedom to those in slavery. This was not acceptable to Johnson or the Cabinet, who sent word for Sherman to secure the surrender without making political deals, which he did. Further, Johnson placed a $100,000 bounty (equivalent to $1.52 million in 2022) on Confederate President Davis, then a fugitive, which gave Johnson the reputation of a man who would be tough on the South. More controversially, he permitted the execution of Mary Surratt for her part in Lincoln's assassination. Surratt was executed with three others, including Atzerodt, on July 7, 1865.[23]

إعادة البناء

خلفية

Upon taking office, Johnson faced the question of what to do with the former Confederacy. President Lincoln had authorized loyalist governments in Virginia, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee as the Union came to control large parts of those states and advocated a ten percent plan that would allow elections after ten percent of the voters in any state took an oath of future loyalty to the Union. Congress considered this too lenient; its own plan, requiring a majority of voters to take the loyalty oath, passed both houses in 1864, but Lincoln pocket vetoed it.[24]

Johnson had three goals in Reconstruction. He sought a speedy restoration of the states, on the grounds that they had never truly left the Union, and thus should again be recognized once loyal citizens formed a government. To Johnson, African-American suffrage was a delay and a distraction; it had always been a state responsibility to decide who should vote. Second, political power in the Southern states should pass from the planter class to his beloved "plebeians". Johnson feared that the freedmen, many of whom were still economically bound to their former masters, might vote at their direction. Johnson's third priority was election in his own right in 1868, a feat no one who had succeeded a deceased president had managed to accomplish, attempting to secure a Democratic anti-Congressional Reconstruction coalition in the South.[25]

The Republicans had formed a number of factions. The Radical Republicans sought voting and other civil rights for African Americans. They believed that the freedmen could be induced to vote Republican in gratitude for emancipation, and that black votes could keep the Republicans in power and Southern Democrats, including former rebels, out of influence. They believed that top Confederates should be punished. The Moderate Republicans sought to keep the Democrats out of power at a national level, and prevent former rebels from resuming power. They were not as enthusiastic about the idea of African-American suffrage as their Radical colleagues, either because of their own local political concerns, or because they believed that the freedman would be likely to cast his vote badly. Northern Democrats favored the unconditional restoration of the Southern states. They did not support African-American suffrage, which might threaten Democratic control in the South.[26]

إعادة البناء الرئاسية

Johnson was initially left to devise a Reconstruction policy without legislative intervention, as Congress was not due to meet again until December 1865.[27] Radical Republicans told the President that the Southern states were economically in a state of chaos and urged him to use his leverage to insist on rights for freedmen as a condition of restoration to the Union. But Johnson, with the support of other officials including Seward, insisted that the franchise was a state, not a federal matter. The Cabinet was divided on the issue.[28]

Johnson's first Reconstruction actions were two proclamations, with the unanimous backing of his Cabinet, on May 29. One recognized the Virginia government led by provisional Governor Francis Pierpont. The second provided amnesty for all ex-rebels except those holding property valued at $20,000 or more; it also appointed a temporary governor for North Carolina and authorized elections. Neither of these proclamations included provisions regarding black suffrage or freedmen's rights. The President ordered constitutional conventions in other former rebel states.[29]

As Southern states began the process of forming governments, Johnson's policies received considerable public support in the North, which he took as unconditional backing for quick reinstatement of the South. While he received such support from the white South, he underestimated the determination of Northerners to ensure that the war had not been fought for nothing. It was important, in Northern public opinion, that the South acknowledge its defeat, that slavery be ended, and that the lot of African Americans be improved. Voting rights were less important—after all, only a handful of Northern states (mostly in New England) gave African-American men the right to vote on the same basis as whites, and in late 1865, Connecticut, Wisconsin, and Minnesota voted down African-American suffrage proposals by large margins. Northern public opinion tolerated Johnson's inaction on black suffrage as an experiment, to be allowed if it quickened Southern acceptance of defeat. Instead, white Southerners felt emboldened. A number of Southern states passed Black Codes, binding African-American laborers to farms on annual contracts they could not quit, and allowing law enforcement at whim to arrest them for vagrancy and rent out their labor. Most Southerners elected to Congress were former Confederates, with the most prominent being Georgia Senator-designate and former Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens. Congress assembled in early December 1865; Johnson's conciliatory annual message to them was well received. Nevertheless, Congress refused to seat the Southern legislators and established a committee to recommend appropriate Reconstruction legislation.[30]

Northerners were outraged at the idea of unrepentant Confederate leaders, such as Stephens, rejoining the federal government at a time when emotional wounds from the war remained raw. They saw the Black Codes placing African Americans in a position barely above slavery. Republicans also feared that restoration of the Southern states would return the Democrats to power.[31][32] In addition, according to David O. Stewart in his book on Johnson's impeachment, "the violence and poverty that oppressed the South would galvanize the opposition to Johnson".[33]

الافتراق عن الجمهوريين: 1866

Congress was reluctant to confront the President, and initially only sought to fine-tune Johnson's policies towards the South.[34] According to Trefousse, "If there was a time when Johnson could have come to an agreement with the moderates of the Republican Party, it was the period following the return of Congress."[35] The President was unhappy about the provocative actions of the Southern states, and about the continued control by the antebellum elite there, but made no statement publicly, believing that Southerners had a right to act as they did, even if it was unwise to do so. By late January 1866, he was convinced that winning a showdown with the Radical Republicans was necessary to his political plans – both for the success of Reconstruction and for reelection in 1868. He would have preferred that the conflict arise over the legislative efforts to enfranchise African Americans in the District of Columbia, a proposal that had been defeated overwhelmingly in an all-white referendum. A bill to accomplish this passed the House of Representatives, but to Johnson's disappointment, stalled in the Senate before he could veto it.[36]

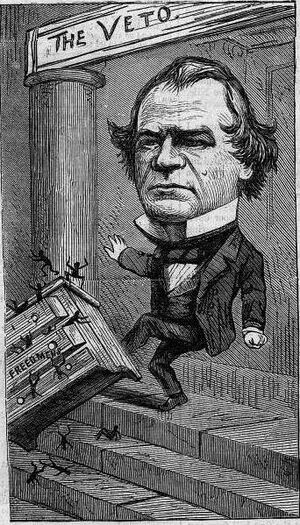

Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull, leader of the Moderate Republicans and Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, was anxious to reach an understanding with the President. He ushered through Congress a bill extending the Freedmen's Bureau beyond its scheduled abolition in 1867, and the first Civil Rights Bill, to grant citizenship to the freedmen. Trumbull met several times with Johnson and was convinced the President would sign the measures (Johnson rarely contradicted visitors, often fooling those who met with him into thinking he was in accord). In fact, the President opposed both bills as infringements on state sovereignty. Additionally, both of Trumbull's bills were unpopular among white Southerners, whom Johnson hoped to include in his new party. Johnson vetoed the Freedman's Bureau bill on February 18, 1866, to the delight of white Southerners and the puzzled anger of Republican legislators. He considered himself vindicated when a move to override his veto failed in the Senate the following day.[36] Johnson believed that the Radicals would now be isolated and defeated and that the moderate Republicans would form behind him; he did not understand that Moderates also wanted to see African Americans treated fairly.[37]

On February 22, 1866, Washington's Birthday, Johnson gave an impromptu speech to supporters who had marched to the White House and called for an address in honor of the first president. In his hour-long speech, he instead referred to himself over 200 times. More damagingly, he also spoke of "men ... still opposed to the Union" to whom he could not extend the hand of friendship he gave to the South.[38][39] When called upon by the crowd to say who they were, Johnson named Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, and abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and accused them of plotting his assassination. Republicans viewed the address as a declaration of war, while one Democratic ally estimated Johnson's speech cost the party 200,000 votes in the 1866 congressional midterm elections.[40]

Although strongly urged by moderates to sign the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Johnson broke decisively with them by vetoing it on March 27. In his veto message, he objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when 11 out of 36 states were unrepresented in the Congress, and that it discriminated in favor of African Americans and against whites.[41][42] Within three weeks, Congress had overridden his veto, the first time that had been done on a major bill in American history.[43] The veto, often seen as a key mistake of Johnson's presidency, convinced moderates there was no hope of working with him. Historian Eric Foner, in his volume on Reconstruction, views it as "the most disastrous miscalculation of his political career". According to Stewart, the veto was "for many his defining blunder, setting a tone of perpetual confrontation with Congress that prevailed for the rest of his presidency".[44]

Congress also proposed the Fourteenth Amendment to the states. Written by Trumbull and others, it was sent for ratification by state legislatures in a process in which the president plays no part, though Johnson opposed it. The amendment was designed to put the key provisions of the Civil Rights Act into the Constitution, but also went further. The amendment extended citizenship to every person born in the United States (except Indians on reservations), penalized states that did not give the vote to freedmen, and most importantly, created new federal civil rights that could be protected by federal courts. It also guaranteed that the federal debt would be paid and forbade repayment of Confederate war debts. Further, it disqualified many former Confederates from office, although the disability could be removed — by Congress, not the president.[45] Both houses passed the Freedmen's Bureau Act a second time, and again the President vetoed it; this time, the veto was overridden. By the summer of 1866, when Congress finally adjourned, Johnson's method of restoring states to the Union by executive fiat, without safeguards for the freedmen, was in deep trouble. His home state of Tennessee ratified the Fourteenth Amendment despite the President's opposition.[46] When Tennessee did so, Congress immediately seated its proposed delegation, embarrassing Johnson.[47]

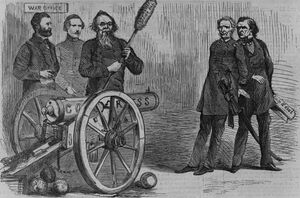

Efforts to compromise failed,[48] and a political war ensued between the united Republicans on one side, and on the other, Johnson and his Northern and Southern allies in the Democratic Party. He called a convention of the National Union Party. Republicans had returned to using their previous identifier; Johnson intended to use the discarded name to unite his supporters and gain election to a full term, in 1868.[49] The battleground was the election of 1866; Southern states were not allowed to vote. Johnson campaigned vigorously, undertaking a public speaking tour, known as the "Swing Around the Circle". The trip, including speeches in Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis, and Columbus, proved politically disastrous, with the President making controversial comparisons between himself and Jesus, and engaging in arguments with hecklers. These exchanges were attacked as beneath the dignity of the presidency. The Republicans won by a landslide, increasing their two-thirds majority in Congress, and made plans to control Reconstruction.[50] Johnson blamed the Democrats for giving only lukewarm support to the National Union movement.[51]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الإعادة الراديكالية للبناء

Even with the Republican victory in November 1866, Johnson considered himself in a strong position. The Fourteenth Amendment had been ratified by none of the Southern or border states except Tennessee, and had been rejected in Kentucky, Delaware, and Maryland. As the amendment required ratification by three-quarters of the states to become part of the Constitution, he believed the deadlock would be broken in his favor, leading to his election in 1868. Once it reconvened in December 1866, an energized Congress began passing legislation, often over a presidential veto; this included the District of Columbia voting bill. Congress admitted Nebraska to the Union over a veto, and the Republicans gained two senators and a state that promptly ratified the amendment. Johnson's veto of a bill for statehood for Colorado Territory was sustained; enough senators agreed that a district with a population of 30,000 was not yet worthy of statehood to win the day.[52]

In January 1867, Congressman Stevens introduced legislation to dissolve the Southern state governments and reconstitute them into five military districts, under martial law. The states would begin again by holding constitutional conventions. African Americans could vote for or become delegates; former Confederates could not. In the legislative process, Congress added to the bill that restoration to the Union would follow the state's ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, and completion of the process of adding it to the Constitution. Johnson and the Southerners attempted a compromise, whereby the South would agree to a modified version of the amendment without the disqualification of former Confederates, and for limited black suffrage. The Republicans insisted on the full language of the amendment, and the deal fell through. Although Johnson could have pocket vetoed the First Reconstruction Act as it was presented to him less than ten days before the end of the Thirty-Ninth Congress, he chose to veto it directly on March 2, 1867; Congress overruled him the same day. Also on March 2, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act over the President's veto, in response to statements during the Swing Around the Circle that he planned to fire Cabinet secretaries who did not agree with him. This bill, requiring Senate approval for the firing of Cabinet members during the tenure of the president who appointed them and for one month afterwards, was immediately controversial, with some senators doubting that it was constitutional or that its terms applied to Johnson, whose key Cabinet officers were Lincoln holdovers.[52]

الإدانة

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was an able and hard-working man, but difficult to deal with.[53] Johnson both admired and was exasperated by his War Secretary, who, in combination with General of the Army Grant, worked to undermine the president's Southern policy from within his own administration. Johnson considered firing Stanton, but respected him for his wartime service as secretary. Stanton, for his part, feared allowing Johnson to appoint his successor and refused to resign, despite his public disagreements with his president.[54]

The new Congress met for a few weeks in March 1867, then adjourned, leaving the House Committee on the Judiciary behind, tasked in the first impeachment inquiry against Johnson with reporting back to the full House whether there were grounds for Johnson to be impeached. This committee duly met, examined the President's bank accounts, and summoned members of the Cabinet to testify. When a federal court released former Confederate president Davis on bail on May 13 (he had been captured shortly after the war), the committee investigated whether the President had impeded the prosecution. It learned that Johnson was eager to have Davis tried. A bipartisan majority of the committee voted down impeachment charges; the committee adjourned on June 3.[55]

Later in June, Johnson and Stanton battled over the question of whether the military officers placed in command of the South could override the civil authorities. The President had Attorney General Henry Stanbery issue an opinion backing his position that they could not. Johnson sought to pin down Stanton either as for, and thus endorsing Johnson's position, or against, showing himself to be opposed to his president and the rest of the Cabinet. Stanton evaded the point in meetings and written communications. When Congress reconvened in July, it passed a Reconstruction Act against Johnson's position, waited for his veto, overrode it, and went home. In addition to clarifying the powers of the generals, the legislation also deprived the President of control over the Army in the South. With Congress in recess until November, Johnson decided to fire Stanton and relieve one of the military commanders, General Philip Sheridan, who had dismissed the governor of Texas and installed a replacement with little popular support. Johnson was initially deterred by a strong objection from Grant, but on August 5, the President demanded Stanton's resignation; the secretary refused to quit with Congress out of session.[56] Johnson then suspended him pending the next meeting of Congress as permitted under the Tenure of Office Act; Grant agreed to serve as temporary replacement while continuing to lead the Army.[57]

Grant, under protest, followed Johnson's order transferring Sheridan and another of the district commanders, Daniel Sickles, who had angered Johnson by firmly following Congress's plan. The President also issued a proclamation pardoning most Confederates, exempting those who held office under the Confederacy, or who had served in federal office before the war but had breached their oaths. Although Republicans expressed anger with his actions, the 1867 elections generally went Democratic. No seats in Congress were directly elected in the polling, but the Democrats took control of the Ohio General Assembly, allowing them to defeat for reelection one of Johnson's strongest opponents, Senator Benjamin Wade. Voters in Ohio, Connecticut, and Minnesota turned down propositions to grant African Americans the vote.[58]

The adverse results momentarily put a stop to Republican calls to impeach Johnson, who was elated by the elections.[59] Nevertheless, once Congress met in November, the Judiciary Committee reversed itself and passed a resolution of impeachment against Johnson. After much debate about whether anything the President had done was a high crime or misdemeanor, the standard under the Constitution, the resolution was defeated by the House of Representatives on December 7, 1867, by a vote of 57 in favor to 108 opposed.[60]

Johnson notified Congress of Stanton's suspension and Grant's interim appointment. In January 1868, the Senate disapproved of his action, and reinstated Stanton, contending the President had violated the Tenure of Office Act. Grant stepped aside over Johnson's objection, causing a complete break between them. Johnson then dismissed Stanton and appointed Lorenzo Thomas to replace him. Stanton refused to leave his office, and on February 24, 1868, the House impeached the President for intentionally violating the Tenure of Office Act, by a vote of 128 to 47. The House subsequently adopted eleven articles of impeachment, for the most part alleging that he had violated the Tenure of Office Act, and had questioned the legitimacy of Congress.[61]

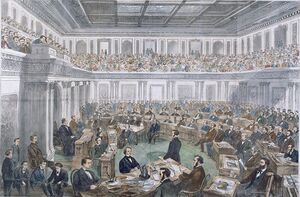

On March 5, 1868, the impeachment trial began in the Senate and lasted almost three months; Congressmen George S. Boutwell, Benjamin Butler and Thaddeus Stevens acted as managers for the House, or prosecutors, and William M. Evarts, Benjamin R. Curtis and former Attorney General Stanbery were Johnson's counsel; Chief Justice Chase served as presiding judge.[62]

The defense relied on the provision of the Tenure of Office Act that made it applicable only to appointees of the current administration. Since Lincoln had appointed Stanton, the defense maintained Johnson had not violated the act, and also argued that the President had the right to test the constitutionality of an act of Congress.[63] Johnson's counsel insisted that he make no appearance at the trial, nor publicly comment about the proceedings, and except for a pair of interviews in April, he complied.[64]

Johnson maneuvered to gain an acquittal; for example, he pledged to Iowa Senator James W. Grimes that he would not interfere with Congress's Reconstruction efforts. Grimes reported to a group of Moderates, many of whom voted for acquittal, that he believed the President would keep his word. Johnson also promised to install the respected John Schofield as War Secretary. [65] Kansas Senator Edmund G. Ross received assurances that the new, Radical-influenced constitutions ratified in South Carolina and Arkansas would be transmitted to the Congress without delay, an action which would give him and other senators political cover to vote for acquittal.[66]

One reason senators were reluctant to remove the President was that his successor would have been Ohio Senator Wade, the president pro tempore of the Senate. Wade, a lame duck who left office in early 1869, was a Radical who supported such measures as women's suffrage, placing him beyond the pale politically in much of the nation.[67][68] Additionally, a President Wade was seen as an obstacle to Grant's ambitions.[69]

With the dealmaking, Johnson was confident of the result in advance of the verdict, and in the days leading up to the ballot, newspapers reported that Stevens and his Radicals had given up. On May 16, the Senate voted on the 11th article of impeachment, accusing Johnson of firing Stanton in violation of the Tenure of Office of Act once the Senate had overturned his suspension. Thirty-five senators voted "guilty" and 19 "not guilty", thus falling short by a single vote of the two-thirds majority required for conviction under the Constitution. Ten Republicans—Senators Grimes, Ross, Trumbull, James Dixon, James Rood Doolittle, Daniel Sheldon Norton, William Pitt Fessenden, Joseph S. Fowler, John B. Henderson, and Peter G. Van Winkle—voted to acquit the President. With Stevens bitterly disappointed at the result, the Senate then adjourned for the Republican National Convention; Grant was nominated for president. The Senate returned on May 26 and voted on the second and third articles, with identical 35–19 results. Faced with those results, Johnson's opponents gave up and dismissed proceedings.[70][71] [72] Stanton "relinquished" his office on May 26, and the Senate subsequently confirmed Schofield.[73] When Johnson renominated Stanbery to return to his position as Attorney General after his service as a defense manager, the Senate refused to confirm him.[74]

Allegations were made at the time and again later that bribery dictated the outcome of the trial. Even when it was in progress, Representative Butler began an investigation, held contentious hearings, and issued a report, unendorsed by any other congressman. Butler focused on a New York–based "Astor House Group", supposedly led by political boss and editor Thurlow Weed. This organization was said to have raised large sums of money from whiskey interests through Cincinnati lawyer Charles Woolley to bribe senators to acquit Johnson. Butler went so far as to imprison Woolley in the Capitol building when he refused to answer questions, but failed to prove bribery.[75]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

السياسة الخارجية

Soon after taking office as president, Johnson reached an accord with Secretary of State William H. Seward that there would be no change in foreign policy. In practice, this meant that Seward would continue to run things as he had under Lincoln. Seward and Lincoln had been rivals for the nomination in 1860; the victor hoped that Seward would succeed him as president in 1869. At the time of Johnson's accession, the French had intervened in Mexico, sending troops there. While many politicians had indulged in saber rattling over the Mexican matter, Seward preferred quiet diplomacy, warning the French through diplomatic channels that their presence in Mexico was unacceptable. Although the President preferred a more aggressive approach, Seward persuaded him to follow his lead. In April 1866, the French government informed Seward that its troops would be brought home in stages, to conclude by November 1867.[76] On August 14, 1866, Johnson and his cabinet gave a reception for Queen Emma of Hawaii who was returning to Hawaii after her trip to Britain and Europe.[77][78][79]

Seward was an expansionist, and sought opportunities to gain territory for the United States. After the loss of the Crimean War in the 1850s, the Russian government saw its North American colony (today Alaska) as a financial liability, and feared losing control to Britain whose troops would easily swoop in and annex the territory from neighboring Canada in any future conflict. Negotiations between Russia and the U.S. over the sale of Alaska were halted due to the outbreak of the Civil War, but after the U.S. victory in the war, talks resumed.[80] Russia instructed its minister in Washington, Baron Eduard de Stoeckl, to negotiate a sale. De Stoeckl did so deftly, getting Seward to raise his offer from $5 million (coincidentally, the minimum that Russia had instructed de Stoeckl to accept) to $7 million, and then getting $200,000 added by raising various objections.[81] This sum of $7.2 million is equivalent to $120 million in present-day terms.[82] On March 30, 1867, de Stoeckl and Seward signed the treaty, working quickly as the Senate was about to adjourn. Johnson and Seward took the signed document to the President's Room in the Capitol, only to be told there was no time to deal with the matter before adjournment. The President summoned the Senate into session to meet on April 1; that body approved the treaty, 37–2.[83] Emboldened by his success in Alaska, Seward sought acquisitions elsewhere. His only success was staking an American claim to uninhabited Wake Island in the Pacific, which would be officially claimed by the U.S. in 1898. He came close with the Danish West Indies as Denmark agreed to sell and the local population approved the transfer in a plebiscite, but the Senate never voted on the treaty and it expired.[84]

Another treaty that fared badly was the Johnson-Clarendon convention, negotiated in settlement of the Alabama Claims, for damages to American shipping from British-built Confederate raiders. Negotiated by the United States Minister to Britain, former Maryland senator Reverdy Johnson, in late 1868, it was ignored by the Senate during the remainder of the President's term. The treaty was rejected after he left office, and the Grant administration later negotiated considerably better terms from Britain.[85][86]

الإدارة ومجلس الوزراء

| حكومة أندرو جونسون | ||

|---|---|---|

| المنصب | الاسم | الفترة |

| الرئيس | أندرو جونسون | 1865 – 1869 |

| نائب الرئيس | none | 1865 – 1869 |

| وزير الخارجية | William H. Seward | 1865 – 1869 |

| وزير الخزانة | Hugh McCulloch | 1865 – 1869 |

| وزير الحربية | Edwin Stanton | 1865 – 1868[أ] |

| John Schofield | 1868 – 1869 | |

| المدعي العام | James Speed | 1865 – 1866 |

| Henry Stanbery | 1866 – 1868 | |

| William M. Evarts | 1868 – 1869 | |

| المدير العام لمصلحة البريد | William Dennison Jr. | 1865 – 1866 |

| Alexander Randall | 1866 – 1869 | |

| وزير البحرية | Gideon Welles | 1865 – 1869 |

| وزير الداخلية | John Palmer Usher | 1865 |

| James Harlan | 1865 – 1866 | |

| Orville Hickman Browning | 1866 – 1869 | |

التعيينات القضائية

Johnson appointed nine Article III federal judges during his presidency, all to United States district courts; he did not appoint a justice to serve on the Supreme Court. In April 1866, he nominated Henry Stanbery to fill the vacancy left with the death of John Catron, but Congress eliminated the seat to prevent the appointment, and to ensure that he did not get to make any appointments eliminated the next vacancy as well, providing that the court would shrink by one justice when one next departed from office.[87] Johnson appointed his Greeneville crony, Samuel Milligan, to the United States Court of Claims, where he served from 1868 until his death in 1874.[88][89]

إصلاحات بدأها

In June 1866, Johnson signed the Southern Homestead Act into law, believing that the legislation would assist poor whites. Around 28,000 land claims were successfully patented, although few former slaves benefitted from the law, fraud was rampant, and much of the best land was off-limits, reserved for grants to veterans or railroads.[90] In June 1868, Johnson signed an eight-hour law passed by Congress that established an eight-hour workday for laborers and mechanics employed by the Federal Government.[91] Although Johnson told members of a Workingmen's party delegation in Baltimore that he could not directly commit himself to an eight-hour day, he nevertheless told the same delegation that he greatly favoured the "shortest number of hours consistent with the interests of all".[92] According to Richard F. Selcer, however, the good intentions behind the law were "immediately frustrated" as wages were cut by 20%.[91]

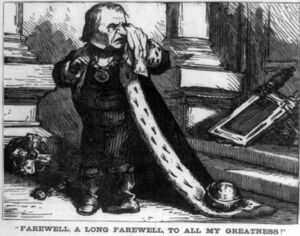

إكماله مدته

Johnson sought nomination by the 1868 Democratic National Convention in New York in July 1868. He remained very popular among Southern whites, and boosted that popularity by issuing, just before the convention, a pardon ending the possibility of criminal proceedings against any Confederate not already indicted, meaning that only Davis and a few others still might face trial. On the first ballot, Johnson was second to former Ohio representative George H. Pendleton, who had been his Democratic opponent for vice president in 1864. Johnson's support was mostly from the South, and fell away as the ballots passed. On the 22nd ballot, former New York governor Horatio Seymour was nominated, and the President received only four votes, all from Tennessee.[93]

The conflict with Congress continued. Johnson sent Congress proposals for amendments to limit the president to a single six-year term and make the president and the Senate directly elected, and for term limits for judges. Congress took no action on them. When the President was slow to officially report ratifications of the Fourteenth Amendment by the new Southern legislatures, Congress passed a bill, again over his veto, requiring him to do so within ten days of receipt. He still delayed as much as he could, but was required, in July 1868, to report the ratifications making the amendment part of the Constitution.[94]

Seymour's operatives sought Johnson's support, but he long remained silent on the presidential campaign. It was not until October, with the vote already having taken place in some states, that he mentioned Seymour at all, and he never endorsed him. Nevertheless, Johnson regretted Grant's victory, in part because of their animus from the Stanton affair. In his annual message to Congress in December, Johnson urged the repeal of the Tenure of Office Act and told legislators that had they admitted their Southern colleagues in 1865, all would have been well. He celebrated his 60th birthday in late December with a party for several hundred children, though not including those of President-elect Grant, who did not allow his to go.[95]

On Christmas Day 1868, Johnson issued a final amnesty, this one covering everyone, including Davis. He also issued, in his final months in office, pardons for crimes, including one for Dr. Samuel Mudd, controversially convicted of involvement in the Lincoln assassination (he had set Booth's broken leg) and imprisoned in Fort Jefferson on Florida's Dry Tortugas.[95]

On March 3, the President hosted a large public reception at the White House on his final full day in office. Grant had made it known that he was unwilling to ride in the same carriage as Johnson, as was customary, and Johnson refused to go to the inauguration at all. Despite an effort by Seward to prompt a change of mind, he spent the morning of March 4 finishing last-minute business, and then shortly after noon rode from the White House to the home of a friend.[96][97]

ما بعد الرئاسة (1869–1875)

After leaving the presidency, Johnson remained for some weeks in Washington, then returned to Greeneville for the first time in eight years. He was honored with large public celebrations along the way, especially in Tennessee, where cities hostile to him during the war hung out welcome banners. He had arranged to purchase a large farm near Greeneville to live on after his presidency.[98]

Some expected Johnson to run for Governor of Tennessee or for the Senate again, while others thought that he would become a railroad executive.[86] Johnson found Greeneville boring, and his private life was embittered by the suicide of his son Robert in 1869.[99] Seeking vindication for himself, and revenge against his political enemies, he launched a Senate bid soon after returning home. Tennessee had gone Republican, but court rulings restoring the vote to some whites and the violence of the Ku Klux Klan suppressing the African-American vote, leading to a Democratic victory in the legislative elections in August 1869. Johnson was seen as a likely victor in the Senate election, although hated by Radical Republicans, and by some Democrats because of his wartime activities. Although he was at one point within a single vote of victory in the legislature's balloting, the Republicans eventually elected Henry Cooper over Johnson, 54–51.[100] In 1872, there was a special election for an at-large congressional seat for Tennessee; Johnson initially sought the Democratic nomination, but when he saw that it would go to former Confederate general Benjamin F. Cheatham, decided to run as an independent. The former president was defeated, finishing third, but the split in the Democratic Party defeated Cheatham in favor of an old Johnson Unionist ally, Horace Maynard.[101]

In 1873, Johnson contracted cholera during an epidemic but recovered; that year he lost about $73,000 when the First National Bank of Washington went under, though he was eventually repaid much of the sum.[102]

العودة لمجلس الشيوخ

He began looking towards the next Senate election to take place in the legislature in early 1875. Johnson began to woo the farmers' Grange movement; with his Jeffersonian leanings, he easily gained their support. He spoke throughout the state in his final campaign tour. Few African Americans outside the large towns were now able to vote as Reconstruction faded in Tennessee, setting a pattern that would be repeated in the other Southern states; the white domination would last almost a century. In the Tennessee legislative elections in August, the Democrats elected 92 legislators to the Republicans' eight, and Johnson went to Nashville for the legislative session. When the balloting for the Senate seat began on January 20, 1875, he led with 30 votes, but did not have the required majority as three former Confederate generals, one former colonel, and a former Democratic congressman split the vote with him. Johnson's opponents tried to agree on a single candidate who might gain majority support and defeat him, but failed, and he was elected on January 26 on the 54th ballot, with a margin of a single vote. Nashville erupted in rejoicing;[103][104] remarked Johnson, "Thank God for the vindication."[99]

Johnson's comeback garnered national attention, with the St. Louis Republican calling it "the most magnificent personal triumph which the history of American politics can show".[104] At his swearing-in in the Senate on March 5, 1875, he was greeted with flowers, and sworn in alongside Hamlin (his predecessor as vice president) by incumbent Vice President Henry Wilson (who as senator had voted for Johnson's ouster). Many Republicans ignored Senator Johnson, though some, such as Ohio's John Sherman (who had voted for conviction), shook his hand. Johnson remains the only former president to serve in the Senate. He spoke only once in the short session, on March 22 lambasting President Grant for his use of federal troops in support of Louisiana's Reconstruction government. The former president asked, "How far off is military despotism?" and concluded his speech, "may God bless this people and God save the Constitution".[105]

الوفاة

Johnson returned home after the special session concluded. In late July 1875, convinced some of his opponents were defaming him in the Ohio gubernatorial race, he decided to travel there to give speeches. He began the trip on July 28, and broke the journey at his daughter Mary's farm near Elizabethton, where his daughter Martha was also staying. That evening he had a stroke, but refused medical treatment until the next day, when he did not improve and two doctors were sent for from Elizabethton. He seemed to respond to their ministrations, but had another stroke on the evening of July 30, and died early the following morning at the age of 66. President Grant had the "painful duty" of announcing the death of the only surviving past president. Northern newspapers, in their obituaries, tended to focus on Johnson's loyalty during the war, while Southern ones paid tribute to his actions as president. Johnson's funeral was held on August 3 in Greeneville.[106][107] He was buried with his body wrapped in an American flag and a copy of the U.S. Constitution placed under his head, according to his wishes. The burial ground was dedicated as the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery in 1906, and with his home and tailor's shop, is part of the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site.[108]

انظر أيضاً

- List of American Civil War generals

- United States presidential election, 1864

- History of the United States (1865-1918)

- Tennessee Johnson

ملاحظات

- ^ Replaced ad interim by Ulysses S. Grant in August 1867 before being reinstated by Congress in January 1868

ببليوجرافيا

- Howard K. Beale, The Critical Year. A Study of Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1930). ISBN 0804410852

- Michael Les Benedict, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (1999). ISBN 0393319822

- Boulard, Garry, "The Swing Around the Circle—Andrew Johnson and the Train Ride that Destroyed a Presidency" (2008) ISBN 978-1-4401-0239-4

- Albert E. Castel, The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (1979). ISBN 0700601902

- D. M. DeWitt, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (1903).

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 'The Transubstantiation of a Poor White' in Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward the History of the Part Which Black People Have Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880 (1935). ISBN 0527252808.

- W. A. Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction (New York, 1898)

- W. A. Dunning, Reconstruction, Political and Economic (New York, 1907) online edition

- Foster, G. Allen, Impeached: The President who almost lost his job (New York, 1964).

- Eric L. McKitrick, Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1961). ISBN 0-19-505707-4

- Martin E. Mantell; Johnson, Grant, and the Politics of Reconstruction (1973)

- Hatfield, Mark O., with the Senate Historical Office, Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993.(U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997), p. 219

- Howard Means, The Avenger Takes His Place: Andrew Johnson and the 45 Days That Changed the Nation (New York, 2006)

- Milton; George Fort. The Age of Hate: Andrew Johnson and the Radicals (1930) online edition

- Patton; James Welch. Unionism and Reconstruction in Tennessee, 1860–1869 (1934) online edition

- Rhodes; James Ford History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 Volume: 6. 1920. Pulitzer prize.

- Schouler, James. History of the United States of America: Under the Constitution vol. 7. 1865–1877. The Reconstruction Period (1917)

- Sledge, James L. III. "Johnson, Andrew" in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. (2000)

- Stewart, David, O. Impeached: the Trial of President Andrew Jackson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (2009) Simon and Schuster, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4165-4749-5.

- Lloyd P. Stryker, Andrew Johnson: A Study in Courage (1929). ISBN 0-403-01231-7 online edition

- Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989). ISBN 0-393-31742-0 online edition

- Winston; Robert W. Andrew Johnson: Plebeian and Patriot (1928) online edition

Primary sources

- Ralph W. Haskins, LeRoy P. Graf, and Paul H. Bergeron et al., eds. The Papers of Andrew Johnson 16 volumes; University of Tennessee Press, (1967–2000). ISBN 1572330910. Includes all letters and speeches by Johnson, and many letters written to him. Complete to 1875.

- Newspaper clippings, 1865–1869

- Series of Harper's Weekly articles covering the impeachment controversy and trial

- Johnson's obituary, from the New York Times

الهامش

- ^ "American President: Andrew Johnson: Family Life". Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Milton, George Fort (1930). The Age of Hate: Andrew Johnson And The Radicals. New York: Coward-McCann. p. 80. ISBN 1417916583. OCLC 739916.

As for my religion, it is the doctrine of the Bible, as taught and practiced by Jesus Christ.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ أ ب Trefousse, p. 177.

- ^ أ ب Castel 1979, p. 9.

- ^ أ ب Gordon-Reed, p. 76.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 178.

- ^ أ ب Trefousse, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 181–185.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 183–187.

- ^ أ ب Gordon-Reed, p. 82.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, p. 85.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 10.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 191.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, p. 87.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 192.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 194.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, p. 90.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, p. 93.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Fitzgerald, p. 26.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 18–21.

- ^ Fitzgerald, p. 28.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 215–216, 234–235.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 50–59.

- ^ Fitzgerald, p. 35.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Stewart, p. 26.

- ^ Fitzgerald, p. 36.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 240.

- ^ أ ب Castel 1979, pp. 62–68.

- ^ Foner, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Foner, p. 249.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Foner, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 70.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 71.

- ^ Stewart, p. 53.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 252.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 271.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 88–89.

- ^ أ ب Castel 1979, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 128–135.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 135–137.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 146.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 313–316.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 316, 336.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 319.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 81.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, p. 139.

- ^ Stewart, p. 307.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 330.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 323–328.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 340–341.

- ^ "Senate Journal. 40th Cong., 2nd sess., 16 / 26 May 1868, 943–51". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 195.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 336.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 240–247, 284–292.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Apoliona, Haunani (January 2010). "Ke Kuini Emalani ko luna" (PDF). Ka Wai Ola. Vol. 27, no. 1. Honolulu. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ Byrd, Jodi A. (2011). The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 177–183. ISBN 978-1-4529-3317-7. OCLC 719427962.

- ^ Kanahele, George S. (1999). Emma: Hawaii's Remarkable Queen. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 189–226. ISBN 978-0-8248-2240-8. OCLC 40890919.

- ^ Claus-M Naske; Herman E. Slotnick (March 15, 1994). Alaska: A History of the 49th State. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-8061-2573-2.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 120.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 120–122.

- ^ David M. Pletcher (1998). The Diplomacy of Trade and Investment: American Economic Expansion in the Hemisphere, 1865–1900. University of Missouri Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8262-1127-9.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 204–205.

- ^ أ ب Trefousse, p. 349.

- ^ Stewart, p. 54.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 363.

- ^ "Milligan, Samuel". Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789-present. Federal Judiciary Center.

- ^ Zuczek, Richard (2006). Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era: M–Z and primary documents. p. 595. ISBN 978-0-313-33075-9.

- ^ أ ب Selcer, Richard F. (May 14, 2014). Civil War America, 1850 To 1875. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4381-0797-4.

- ^ Smalley, p. 80.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 337–339.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 340–343.

- ^ أ ب Trefousse, pp. 345–347.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 348, 353–354.

- ^ أ ب Gordon-Reed, p. 142.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Castel 1979, p. 215.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 364–366.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 334, 370–371.

- ^ أ ب Castel 1979, p. 216.

- ^ Castel 1979, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 375–377.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, p. 143.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 377.

وصلات خارجية

- أعمال من Andrew Johnson في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- The Impeachment trial of President Johnson as reported in Harper's Monthly Magazine April 1868

- Obituary, NY Times, August 1, 1875, Andrew Johnson Dead

- Articles of Impeachment

- White House Biography

- Vice Presidential biography. From the Senate Historical Office.

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: Andrew Johnson

- Andrew Johnson Cleveland Speech (September 3, 1866)

- Congressional Globe transcript of Johnsons inaugural address

- Speeches of Andrew Johnson : President of the United States 1866 collection at archive.org

- Andrew Johnson's 200th Birthday Celebration site at DiscoverGreeneville.com

- Andrew Johnson: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Andrew Johnson Papers, 1846-1875

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Papers of Governor Andrew Johnson, 1853-1857

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Papers of (Military) Governor Andrew Johnson, 1862-1865

- أندرو جونسون at the دليل سـِيَر الكونگرس الأمريكي Retrieved on 2009-03-02

- Essay on Andrew Johnson and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Paper comparing the impeachments of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton

|}

- CS1 errors: redundant parameter

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- United States Senators from Tennessee

- أندرو جونسون

- United States presidential candidates, 1860

- United States presidential candidates, 1868

- جنرالات جيش الاتحاد

- حكام تنسي

- Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee

- Tennessee State Senators

- Burials in Tennessee

- وفيات بنوبة قلبية

- Members of the Tennessee House of Representatives

- Mayors of places in Tennessee

- Tennessee city councillors

- People from Raleigh, North Carolina

- Union political leaders

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- ديمقراطيو تنسي

- People of Tennessee in the American Civil War

- مسؤولون مدانون بالولايات المتحدة

- Scots-Irish Americans

- People of North Carolina in the American Civil War

- People of American Reconstruction

- People from Greeneville, Tennessee

- People from Greene County, Tennessee

- مواليد 1808

- وفيات 1875

- رؤساء الولايات المتحدة في القرن 19

- نواب رؤساء الولايات المتحدة في القرن 19

- رؤساء الولايات المتحدة