جستنيان الثاني

| جستنيان الثاني Ιουστινιανός Β' | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| امبراطور الامبراطورية البيزنطية | |||||

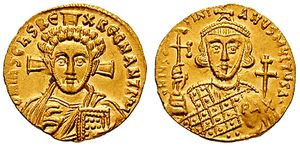

جستنيان، على ظهر عملة ذهبية. | |||||

| عهده الأول عهده الثاني | 685–695 705 – ديسمبر 711 | ||||

| سبقه | قسطنطين الرابع تيبريوس الثالث | ||||

| تبعه | ليونتيوس فيليپيكوس | ||||

| وُلِد | ح.668 القسطنطينية | ||||

| توفي | 11 ديسمبر، 711 (عمره 42) داماتريس، اوپسيكيون | ||||

| الزوج | أودوكيا تيودورا من خازاريا | ||||

| الأنجال | أنستاسيا تيبريوس | ||||

| |||||

| الأسرة المالكة | هراكليان | ||||

| الأب | قسطنطين الرابع | ||||

| الأم | أناستاسيا | ||||

| الأسرة الهرقلية | |||

| تأريخ | |||

| هرقل | 610–641 | ||

| مع قسطنطين 3 كامبراطور مشارك، 613–641 | |||

| قسطنطين الثالث | 641 | ||

| مع هرقلوناس كامبراطور مشارك | |||

| هرقلوناس | 641 | ||

| قنسطنس الثاني | 641–668 | ||

| مع قسطنطين الرابع (654–668)، هرقل وتيبريوس (659–668) كأباطرة مشاركين | |||

| قسطنطين الرابع | 668–685 | ||

| مع هرقل وتيبريوس (668–681), وجستنيان الثاني (681–685) كأباطرة مشاركين | |||

| جستنيان الثاني | 685–695, 705–711 | ||

| مع تيبريوس كامبراطور مشارك، 706–711 | |||

| الخلافة | |||

| سبقه الأسرة الجستنية وفوكاس |

تبعه فوضى العشرين عام | ||

| فوضى العشرين عام | ||

|---|---|---|

| تأريخ | ||

|

||

| التعاقب | ||

|

||

جستنيان الثاني Justinian II (باليونانية: Ἰουστινιανός Β΄، أيوستينيانوس الثاني، لاتينية: Iustinianus II) (669 – 11 ديسمبر 711)، لقبه Rhinotmetos أو Rhinotmetus (ὁ Ῥινότμητος, "the مشقوق-الأنف")، هو آخر امبراطور بيزنطي من الأسرة الهرقلية، حكم من عام 685 حتى 695 ومرة أخرى من 705 حتى 711. كان جستنيان الثاني حاكم طموح ومتحمس الذي كان حريصاً على استعادة أمجاد الامبراطورية السابقة، لكن استجابته كانت سيئة تجاه أي معارضة لإرادته وكان يفتقد دهاء والده، قسطنطين الرابع.[1] نتيجة لذلك، تكونت معارضة هائلة لحكمه، مما أسفر عن خلعه عام 685 بمساعدة الجيش البلغاري والسلاڤي. كان عهده الثاني أكثر استبداداً عن الأول، وشهد أيضاً الإطاحة به عام 711، وتخلى عنه جيشه الذي انقلب عليه قبل قتله.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

عهده الأول

Justinian II was the eldest son of Emperor Constantine IV and Anastasia.[2] His father appointed him as his heir sometime after October 681, on the deposition of his uncles Heraclius and Tiberius.[أ] In 685, at the age of sixteen, Justinian II succeeded his father as sole emperor.[4][5]

Due to Constantine IV's victories, the situation in the Eastern provinces of the Empire was stable when Justinian ascended the throne.[6] After a preliminary strike against the Arabs in Armenia,[7] Justinian managed to augment the sum paid by the Umayyad Caliphs as an annual tribute, and to regain control of part of Cyprus.[6] The incomes of the provinces of Armenia and Iberia were divided among the two empires.[8] In 687, as part of his agreements with the Caliphate, Justinian removed from their native Lebanon 12,000 Christian Maronites, who continually resisted the Arabs.[9] Additional resettlement efforts, aimed at the Mardaites and inhabitants of Cyprus, allowed Justinian to reinforce naval forces depleted by earlier conflicts.[8] In 688, Justinian signed a treaty with the Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan which rendered Cyprus neutral ground, with its tax revenue split.[10]

Justinian could now turn his attention to the Balkans, where much imperial territory had been lost to Slavic tribes.[9] In 687 Justinian transferred cavalry troops from Anatolia to Thrace. With a great military campaign in 688–689, Justinian defeated the Slavs of Macedonia and was finally able to enter Thessalonica, the second most important Byzantine city in Europe.[8]

The subdued Slavs were resettled in Anatolia, where they were to provide a military force of 30,000 men.[8] Emboldened by the increase of his forces in Anatolia, Justinian now renewed the war against the Arabs,[11] winning a battle in Armenia in 693. The Arabs met the challenge by bribing the new army to revolt. Most of the Slavic troops defected during the subsequent Battle of Sebastopolis,[12] where Justinian was comprehensively defeated and compelled to flee to the Propontis.[11] There, according to Theophanes,[13] he took out his frustration by slaughtering as many of the Slavs in and around Opsikion as he could lay his hands on.[14] Meanwhile, a Patrician named Symbatius rebelled in Armenia[11] and opened up the province to the Arabs, who proceeded to conquer it in 694–695.[8]

In domestic affairs, the Emperor's bloody persecution of the Manichaeans[5] and suppression of popular traditions of non-Chalcedonian origin caused dissension within the Church.[2] In 692 Justinian convened the so-called Quinisext Council at Constantinople to put his religious policies into effect.[15] The Council expanded and clarified the rulings of the Fifth and Sixth ecumenical councils, but by highlighting differences between the Eastern and Western observances (such as the marriage of priests and the Catholic practice of fasting on Saturdays) it also compromised Byzantine relations with the Catholic Church.[16] The emperor ordered Pope Sergius I arrested, but the militias of Rome and Ravenna rebelled and took the Pope's side.[8]

Justinian contributed to the development of the thematic organization of the Empire, creating a new theme of Hellas in southern Greece and numbering the heads of the four major themes of the Opsikion, Anatolikon, Thracesion and Armeniakon, and the naval Karabisianoi corps, among the senior administrators of the Empire.[8] He also sought to protect the rights of peasant freeholders, who served as the main recruitment pool for the imperial armies, against attempts by the aristocracy to acquire their land. This put him in direct conflict with some of the largest landholders in the Empire.[8]

While his land policies threatened the aristocracy, his tax policy was very unpopular with the common people.[8] Through his agents Stephen and Theodotos, the emperor raised the funds to gratify his sumptuous tastes and his mania for erecting costly buildings.[8][5] This, ongoing religious discontent, conflicts with the aristocracy, and displeasure over his resettlement policy eventually drove his subjects into rebellion.[15] In 695 the population rose under Leontios, the strategos of Hellas, and proclaimed him Emperor.[8][5] Justinian was deposed and his nose was cut off (later replaced by a solid gold replica of his original) to prevent his again seeking the throne: such mutilation was common in Byzantine culture. He was exiled to Cherson in the Crimea.[8] Leontius, after a reign of three years, was in turn dethroned and imprisoned by Tiberius Apsimarus, who next assumed the throne.[17][5]

المنفى

While in exile, Justinian began to plot and gather supporters for an attempt to retake the throne.[18] Justinian became a liability to Cherson and the authorities decided to return him to Constantinople in 702 or 703.[6] He escaped from Cherson and received help from Busir, the khagan of the Khazars, who received him enthusiastically and gave him his sister as a bride.[18] Justinian renamed her Theodora, after the wife of Justinian I.[19] They were given a home in the town of Phanagoria, at the entrance to the sea of Azov. Busir was offered a bribe by Tiberius to kill his brother-in-law, and dispatched two Khazar officials, Papatzys and Balgitzin, to do the deed.[20] Warned by his wife, Justinian executed Papatzys and Balgitzin. He sailed in a fishing boat to Cherson, summoned his supporters, and they all sailed westwards across the Black Sea.[21]

As the ship bearing Justinian sailed along the northern coast of the Black Sea, he and his crew became caught up in a storm somewhere between the mouths of the Dniester and the Dnieper Rivers.[20] While it was raging, one of his companions reached out to Justinian saying that if he promised God that he would be magnanimous, and not seek revenge on his enemies when he was returned to the throne, they would all be spared.[21] Justinian retorted: "If I spare a single one of them, may God drown me here".[20]

Having survived the storm, Justinian next approached Tervel of Bulgaria.[21] Tervel agreed to provide all the military assistance necessary for Justinian to regain his throne in exchange for financial considerations, the award of a Caesar's crown, and the hand of Justinian's daughter, Anastasia, in marriage.[18] In spring 705, with an army of 15,000 Bulgar and Slav horsemen, Justinian appeared before the walls of Constantinople.[18] For three days, Justinian tried to convince the citizens of Constantinople to open the gates, but to no avail.[22] Unable to take the city by force, he and some companions entered through an unused water conduit under the walls of the city, roused their supporters, and seized control of the city in a midnight coup d'état.[18] On 21 August,[23] Justinian regained the throne, breaking the tradition preventing the mutilated from Imperial rule. After tracking down his predecessors, he had his rivals Leontius and Tiberius brought before him in chains in the Hippodrome. There, before a jeering populace, Justinian, now wearing a golden nasal prosthesis,[24] placed his feet on the necks of Tiberius and Leontius in a symbolic gesture of subjugation before ordering their execution by beheading, followed by many of their partisans,[25] as well as deposing, blinding and exiling Patriarch Callinicus I to Rome.[26]

عهده الثاني

Justinian's second reign was marked by unsuccessful warfare against Bulgaria and the Caliphate, and by cruel suppression of opposition at home.[27] In 708 Justinian turned on Bulgarian Khan Tervel, whom he had earlier crowned caesar, and invaded Bulgaria, apparently seeking to recover the territories ceded to Tervel as a reward for his support in 705.[25] The Emperor was defeated, blockaded in Anchialus, and forced to retreat.[25] Peace between Bulgaria and Byzantium was quickly restored. This defeat was followed by Arab victories in Asia Minor,[5] where the cities of Cilicia fell into the hands of the enemy, who penetrated into Cappadocia in 709–711.[27]

He ordered Pope John VII to recognize the decisions of the Quinisext Council and simultaneously fitted out a punitive expedition against Ravenna in 709 under the command of the Patrician Theodore.[28] The expedition was led to reinstate the Western Church's authority over Ravenna, which was taken as a sign of disobedience to the emperor, and revolutionary sentiment.[29] The repression succeeded, and the new Pope Constantine visited Constantinople in 710. Justinian, after receiving Holy Communion at the hands of the pope, renewed all the privileges of the Roman Church. Exactly what passed between them on the subject of the Quinisext Council is not known. It would appear, however, that Constantine approved most of the canons.[30] This would be the last time a Pope visited the city until the visit of Pope Paul VI to Istanbul in 1967.[24]

Justinian's rule provoked another uprising against him.[31] Cherson revolted, and under the leadership of the exiled general Bardanes the city held out against a counter-attack. Soon, the forces sent to suppress the rebellion joined it.[6] The rebels then seized the capital and proclaimed Bardanes as Emperor Philippicus;[32] Justinian had been on his way to Armenia, and was unable to return to Constantinople in time to defend it.[33] He was arrested and executed in November 711, his head being exhibited in Rome and Ravenna.[2]

On hearing the news of his death, Justinian's mother took his six-year-old son and co-emperor, Tiberius, to sanctuary at St. Mary's Church in Blachernae, but was pursued by Philippicus' henchmen, who dragged the child from the altar and, once outside the church, murdered him, thus eradicating the line of Heraclius.[33]

ذكراه

| Justinian II | |

|---|---|

| ملف:Solidus of Justinian II, 2nd reign.jpg Justinian II Solidus | |

| Emperor | |

مكرّم في | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| عيده | 2 August |

Justinian's reign saw the continued slow and ongoing process of transformation of the Byzantine Empire, as the traditions inherited from the ancient Latin Roman state were gradually being eroded. This is most clearly seen in the coinage of Justinian's reign, which saw the reintroduction of the Loros, the traditional consular costume that had not been seen on Imperial coinage for a century, while the office itself had not been celebrated for nearly half a century.[34] This was linked to Justinian's decision to unify the office of consul with that of emperor thus making the Emperor the head of state not only de facto but also de jure. Although the office of the consulate would continue to exist until Emperor Leo VI the Wise formally abolished it with Novel 94,[35] it was Justinian who effectively brought the consulate as a separate political entity to an end. He was formally appointed as Consul in 686,[36] and from that point, Justinian II adopted the title of consul for all the Julian years of his reign, consecutively numbered.

Though at times undermined by his own despotic tendencies, Justinian was a talented and perceptive ruler who succeeded in improving the standing of the Byzantine Empire.[24] A pious ruler, Justinian was the first emperor to include the image of Christ on coinage issued in his name[2] and attempted to outlaw various pagan festivals and practices that persisted in the Empire.[8] He may have self-consciously modelled himself on his namesake, Justinian I,[7] as seen in his enthusiasm for large-scale construction projects and the renaming of his Khazar wife with the name of Theodora.[8] Among the building projects he undertook was the creation of the triklinos, an extension to the imperial palace, a decorative cascade fountain located at the Augusteum, and a new Church of the Virgin at Petrion.[37]

Justinian II is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church on 2 August.[38][39]

العائلة

By his first wife Eudokia, Justinian II had at least one daughter, Anastasia, who was betrothed to the Bulgarian ruler Tervel. By his second wife, Theodora of Khazaria, Justinian II had a son, Tiberius, co-emperor from 706 to 711.

روايات تاريخية

في الثقافة الشعبية

ظهرت شخصية جستنيان الثاني في مسلسل فارس بني مروان وجسدها الممثل جمال سليمان.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

مراجع أساسية

Theophanes, Chronographia.

مراجع ثانوية

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- Norwich, John Julius (1990), Byzantium: The Early Centuries, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-011447-5

- Ostrogorsky, George; Hussey (trans.), Joan (1957), History of the Byzantine state, New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-0599-2

- Canduci, Alexander (2010), Triumph & Tragedy: The Rise and Fall of Rome's Immortal Emperors, Pier 9, ISBN 978-1-74196-598-8

- Moore, R. Scott, "Justinian II (685–695 & 705–711 A.D.)", De Imperatoribus Romanis (1998)

- Bury, J.B., A History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene, Vol. II, MacMillan & Co., 1889

- تحوي هذه المقالة معلومات مترجمة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية لسنة 1911 وهي الآن من ضمن الملكية العامة.

ملاحظات

- ^ Theophanes the Confessor states that Constantine ruled alongside Justinian after the fall of Heraclius and Tiberius. However, all the evidence indicates that he became augustus only on his father's death.[3]

المصادر

- ^ Ostrogorsky, pgs. 116–122

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKazhdan, p. 1084 - ^ Grierson 1968, pp. 512–514.

- ^ Grierson 1968, p. 568.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 15 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 602.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 15 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 602. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ أ ب ت ث Moore 1998

- ^ أ ب Norwich 1990, p. 328

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةOstrogorsky, pp. 116-122 - ^ أ ب Bury 1889, p. 321

- ^ Romilly J.H. Jenkins (1970), Studies on Byzantine History of the 9th and 10th Centuries, p. 271.

- ^ أ ب ت Bury 1889, p. 322

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 330

- ^ Theophanes: AM 6183

- ^ Norwich 1990, pp. 330–331

- ^ أ ب Bury 1889, p. 327

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 332

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 354

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Ostrogorsky 1956, pp. 124–126

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 358

- ^ أ ب ت Bury 1889, p. 359

- ^ أ ب ت Norwich 1990, p. 336

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 360

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTombs - ^ أ ب ت Norwich 1990, p. 345

- ^ أ ب ت Bury 1889, p. 361

- ^ Norwich, p. 338

- ^ أ ب Norwich 1990, pp. 339

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 366

- ^ Liber pontificalis 1:389

- ^ Pope Constantine. New Advent

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 342

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 343

- ^ أ ب Bury 1889, pp. 365–366

- ^ Grypeou, Emmanouela (2006). The encounter of Eastern Christianity with early Islam, BRILL, 2006, p. 69

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 526

- ^ Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, Book V Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine (Chapter VII)

- ^ Bury 1889, pp. 325–326

- ^ "Αυτοκράτορες που έγιναν Άγιοι". 3gym-mikras.thess.sch.gr. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- ^ "Ορθόδοξος Συναξαριστής :: Άγιος Ιουστινιανός Β' ο βασιλιάς". www.saint.gr. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

وصلات خارجية

| Justinian II

]].جستنيان الثاني وُلِد: 669 توفي: ديسمبر 711

| ||

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه قسطنطين الرابع |

الامبراطور البيزنطي 685–695 مع قسطنطين الرابع، 681–685 |

تبعه ليونتيوس |

| سبقه تيبريوس الثالث |

الامبراطور البيزنطي 705–711 مع تيبريوس، 706–711 |

تبعه فيليپيكوس |

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- مقالات مأخوذة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية

- أباطرة بيزنطيون من القرن السابع

- أباطرة بيزنطيون من القرن الثامن

- أسرة هرقل

- بيزنطيون من العرب البيزنطية العربية

- مواليد 669

- وفيات 711

- بيزنطيون معدمون

- قناصل الامبراطورية الرومانية

- قرم العصور الوسطى

- Twenty Years' Anarchy

- عقد 680 في الامبراطورية البيزنطية

- عقد 700 في الامبراطورية البيزنطية

- عقد 710 في الامبراطورية البيزنطية