أقمار أورانوس

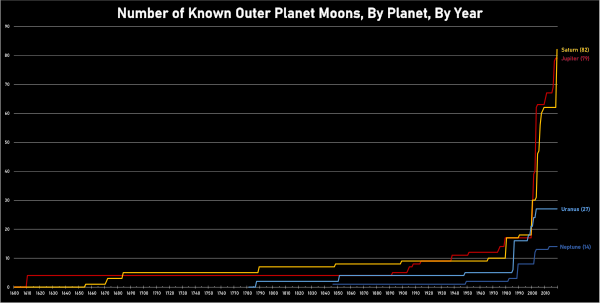

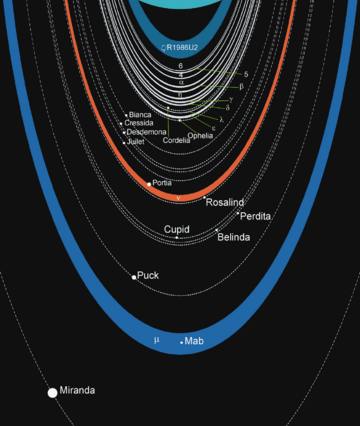

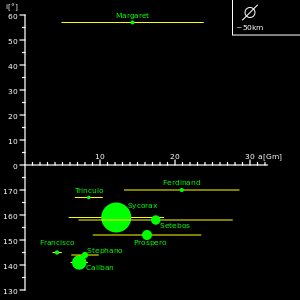

Uranus, the seventh planet of the Solar System, has 27 known moons, most of which are named after characters that appear in, or are mentioned in, the works of William Shakespeare and Alexander Pope.[1] Uranus's moons are divided into three groups: thirteen inner moons, five major moons, and nine irregular moons. The inner and major moons all have prograde orbits, while orbits of the irregulars are mostly retrograde. The inner moons are small dark bodies that share common properties and origins with Uranus's rings. The five major moons are ellipsoidal, indicating that they reached hydrostatic equilibrium at some point in their past (and may still be in equilibrium), and four of them show signs of internally driven processes such as canyon formation and volcanism on their surfaces.[2] The largest of these five, Titania, is 1,578 km in diameter and the eighth-largest moon in the Solar System, about one-twentieth the mass of the Earth's Moon. The orbits of the regular moons are nearly coplanar with Uranus's equator, which is tilted 97.77° to its orbit. Uranus's irregular moons have elliptical and strongly inclined (mostly retrograde) orbits at large distances from the planet.[3]

William Herschel discovered the first two moons, Titania and Oberon, in 1787. The other three ellipsoidal moons were discovered in 1851 by William Lassell (Ariel and Umbriel) and in 1948 by Gerard Kuiper (Miranda).[1] These five may be in hydrostatic equilibrium, and so would be considered dwarf planets if they were in direct orbit about the Sun. The remaining moons were discovered after 1985, either during the Voyager 2 flyby mission or with the aid of advanced Earth-based telescopes.[2][3]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاكتشاف

The first two moons to be discovered were Titania and Oberon, which were spotted by Sir William Herschel on January 11, 1787, six years after he had discovered the planet itself. Later, Herschel thought he had discovered up to six moons (see below) and perhaps even a ring. For nearly 50 years, Herschel's instrument was the only one with which the moons had been seen.[4] In the 1840s, better instruments and a more favorable position of Uranus in the sky led to sporadic indications of satellites additional to Titania and Oberon. Eventually, the next two moons, Ariel and Umbriel, were discovered by William Lassell in 1851.[5] The Roman numbering scheme of Uranus's moons was in a state of flux for a considerable time, and publications hesitated between Herschel's designations (where Titania and Oberon are Uranus II and IV) and William Lassell's (where they are sometimes I and II).[6] With the confirmation of Ariel and Umbriel, Lassell numbered the moons I through IV from Uranus outward, and this finally stuck.[7] In 1852, Herschel's son John Herschel gave the four then-known moons their names.[8]

الأسماء

Although the first two Uranian moons were discovered in 1787, they were not named until 1852, a year after two more moons had been discovered. The responsibility for naming was taken by John Herschel, son of the discoverer of Uranus. Herschel, instead of assigning names from Greek mythology, named the moons after magical spirits in English literature: the fairies Oberon and Titania from William Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, and the sylph Ariel and gnome Umbriel from Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock (Ariel is also a sprite in Shakespeare's The Tempest). The reasoning was presumably that Uranus, as god of the sky and air, would be attended by spirits of the air.[9]

Subsequent names, rather than continuing the airy spirits theme (only Puck and ماب continued the trend), have focused on Herschel's source material. In 1949, the fifth moon, ميراندا, was named by its discoverer Gerard Kuiper after a thoroughly mortal character in Shakespeare's The Tempest. The current IAU practice is to name moons after characters from Shakespeare's plays and The Rape of the Lock (although at present only Ariel, Umbriel, and Belinda have names drawn from the latter; all the rest are from Shakespeare). The outer retrograde moons are all named after characters from one play, The Tempest; the sole known outer prograde moon, Margaret, is named from Much Ado About Nothing.[8]

- The Rape of the Lock (قصيدة من ألكسندر پوپ):

- آرييل، أمبرييل وبليندا

- Plays by وليام شيكسپير:

- A Midsummer Night's Dream: تيتانيا، أوبيرون وپك

- The Tempest: (Ariel), Miranda, Caliban, Sycorax, Prospero, Setebos, Stephano, Trinculo, Francisco, Ferdinand

- الملك لير: كوردليا

- هاملت: Ophelia

- The Taming of the Shrew: بيانكا

- Troilus and Cressida: Cressida

- عطيل: ديدمونة

- Romeo and Juliet: Juliet, Mab

- The Merchant of Venice: Portia

- As You Like It: Rosalind

- Much Ado About Nothing: Margaret

- The Winter's Tale: Perdita

- Timon of Athens: Cupid

Some asteroids, also named after the same Shakespearean characters, share names with moons of Uranus: 171 Ophelia, 218 Bianca, 593 Titania, 666 Desdemona, 763 Cupido, and 2758 Cordelia.

السمات والمجموعات

The Uranian satellite system is the least massive among those of the giant planets. Indeed, the combined mass of the five major satellites is less than half that of Triton (the seventh-largest moon in the Solar System) alone.[أ] The largest of the satellites, Titania, has a radius of 788.9 km,[11] or less than half that of the Moon, but slightly more than that of Rhea, the second-largest moon of Saturn, making Titania the ثامن أكبر قمر في المجموعة الشمسية. Uranus is about 10,000 times more massive than its moons.[ب]

الأقمار الداخلية

الأقمار الكبيرة

الأقمار غير المنتظمة

القائمة

| ¡ الأقمار الداخلية |

† الأقمار الرئيسية |

‡ الأقمار غير المنتظمة (retrograde) |

± قمر غير منتظم (prograde) |

الأقمار الأورانية مسرودة هنا حسب الدورة المدارية، من الأقصر إلى الأطول. Moons massive enough for their surfaces to have collapsed into a spheroid are highlighted in light blue and bolded. The inner and major moons all have prograde orbits. Irregular moons with retrograde orbits are shown in dark grey. Margaret, the only known irregular moon of Uranus with a prograde orbit, is shown in light grey. The orbits and mean distances of the irregular moons are variable over short timescales due to frequent planetary and solar perturbations, therefore the listed orbital elements of all irregular moons are averaged over a 8,000-year numerical integration by Brozović and Jacobson (2009).[12] Their orbital elements are all based on the epoch of 1 January 2000 Terrestrial Time.[13]

| الترتيب [ت] |

Label [ث] |

الاسم | النطق (key) |

الصورة | قدر م. |

Diameter (km)[ج] |

Mass (× 1016 kg)[ح] |

Semi-major axis (km)[13] |

Orbital period (d)[13][خ] |

Inclination (°)[13][د] |

Eccentricity [19] |

Discovery year[1] |

Discoverer [1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VI | ¡Cordelia | /kɔːrˈdiːliə/ | 10.3 | 40 ± 6 (50 × 36) |

≈ 4.4 | 49770 | +0.33503 | 0.08479° | 0.00026 | 1986 | Terrile (Voyager 2) | |

| 2 | VII | ¡Ophelia | /oʊ-ˈfiːliə/ |  |

10.2 | 43 ± 8 (54 × 38) |

≈ 5.3 | 53790 | +0.37640 | 0.1036° | 0.00992 | 1986 | Terrile (Voyager 2) |

| 3 | VIII | ¡Bianca | /biˈɑːŋkə/ |  |

9.8 | 51 ± 4 (64 × 46) |

≈ 9.2 | 59170 | +0.43458 | 0.193° | 0.00092 | 1986 | Smith (Voyager 2) |

| 4 | IX | ¡Cressida | /ˈkrɛsədə/ | 8.9 | 80 ± 4 (92 × 74) |

≈ 34 | 61780 | +0.46357 | 0.006° | 0.00036 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) | |

| 5 | X | ¡Desdemona | /ˌdɛzdəˈmoʊnə/ | 9.3 | 64 ± 8 (90 × 54) |

≈ 18 | 62680 | +0.47365 | 0.11125° | 0.00013 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) | |

| 6 | XI | ¡Juliet | /ˈdʒuːliət/ |  |

8.5 | 94 ± 8 (150 × 74) |

≈ 56 | 64350 | +0.49307 | 0.065° | 0.00066 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

| 7 | XII | ¡Portia | /ˈpɔərʃə/ | 7.7 | 135 ± 8 (156 × 126) |

≈ 170 | 66090 | +0.51320 | 0.059° | 0.00005 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) | |

| 8 | XIII | ¡Rosalind | /ˈrɒzələnd/ | 9.1 | 72 ± 12 | ≈ 25 | 69940 | +0.55846 | 0.279° | 0.00011 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) | |

| 9 | XXVII | ¡Cupid | /ˈkjuːpəd/ | 12.6 | ≈ 18 | ≈ 0.38 | 74800 | +0.61800 | 0.100° | 0.0013 | 2003 | Showalter and Lissauer | |

| 10 | XIV | ¡Belinda | /bəˈlɪndə/ | 8.8 | 90 ± 16 (128 × 64) |

≈ 49 | 75260 | +0.62353 | 0.031° | 0.00007 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) | |

| 11 | XXV | ¡Perdita | /ˈpɜːrdətə/ | 11.0 | 30 ± 6 | ≈ 1.8 | 76400 | +0.63800 | 0.0° | 0.0012 | 1999 | Karkoschka (Voyager 2) | |

| 12 | XV | ¡Puck | /ˈpʌk/ | 7.3 | 162 ± 4 | ≈ 290 | 86010 | +0.76183 | 0.3192° | 0.00012 | 1985 | Synnott (Voyager 2) | |

| 13 | XXVI | ¡Mab | /ˈmæb/ | 12.1 | ≈ 25 | ≈ 1.0 | 97700 | +0.92300 | 0.1335° | 0.0025 | 2003 | Showalter and Lissauer | |

| 14 | V | †Miranda | /məˈrændə/ | 3.5 | 471.6 ± 1.4 (481 × 468 × 466) |

6400±300 | 129390 | +1.41348 | 4.232° | 0.0013 | 1948 | Kuiper | |

| 15 | I | †Ariel | /ˈɛəriɛl/ | 1.0 | 1157.8±1.2 (1162 × 1156 × 1155) |

125100±2100 | 191020 | +2.52038 | 0.260° | 0.0012 | 1851 | Lassell | |

| 16 | II | †Umbriel | /ˈʌmbriɛl/ | 1.7 | 1169.4±5.6 | 127500±2800 | 266300 | +4.14418 | 0.205° | 0.0039 | 1851 | Lassell | |

| 17 | III | †Titania | /təˈtɑːniə/ | 0.8 | 1576.8±1.2 | 340000±6100 | 435910 | +8.70587 | 0.340° | 0.0011 | 1787 | Herschel | |

| 18 | IV | †Oberon | /ˈoʊbərɒn/ | 1.0 | 1522.8±5.2 | 307600±8700 | 583520 | +13.4632 | 0.058° | 0.0014 | 1787 | Herschel | |

| 19 | XXII | ‡Francisco | /frænˈsɪskoʊ/ | 12.4 | ≈ 22 | ≈ 0.72 | 4282900 | −267.09 | 147.250° | 0.1324 | 2003[ذ] | Holman et al. | |

| 20 | XVI | ‡Caliban | /ˈkælɪbæn/ | 9.1 | 42+20 −12 |

≈ 25 | 7231100 | −579.73 | 141.529° | 0.1812 | 1997 | Gladman et al. | |

| 21 | XX | ‡Stephano | /ˈstɛfənoʊ/ |  |

9.7 | ≈ 32 | ≈ 2.2 | 8007400 | −677.47 | 143.819° | 0.2248 | 1999 | Gladman et al. |

| 22 | XXI | ‡Trinculo | /ˈtrɪŋkjʊloʊ/ | 12.7 | ≈ 18 | ≈ 0.39 | 8505200 | −749.40 | 166.971° | 0.2194 | 2001 | Holman et al. | |

| 23 | XVII | ‡Sycorax | /ˈsɪkəræks/ | 7.4 | 157+23 −15 |

≈ 230 | 12179400 | −1288.38 | 159.420° | 0.5219 | 1997 | Nicholson et al. | |

| 24 | XXIII | ±Margaret | /ˈmɑːrɡərət/ | 12.7 | ≈ 20 | ≈ 0.54 | 14146700 | +1661.00 | 57.367° | 0.6772 | 2003 | Sheppard and Jewitt | |

| 25 | XVIII | ‡Prospero | /ˈprɒspəroʊ/ |  |

10.5 | ≈ 50 | ≈ 8.5 | 16276800 | −1978.37 | 151.830° | 0.4445 | 1999 | Holman et al. |

| 26 | XIX | ‡Setebos | /ˈsɛtɛbʌs/ |  |

10.7 | ≈ 48 | ≈ 7.5 | 17420400 | −2225.08 | 158.235° | 0.5908 | 1999 | Kavelaars et al. |

| 27 | XXIV | ‡Ferdinand | /ˈfɜːrdənænd/ | 12.5 | ≈ 20 | ≈ 0.54 | 20430000 | −2790.03 | 169.793° | 0.3993 | 2003[ذ] | Holman et al. |

Sources: NASA/NSSDC,[13] Sheppard, et al. 2005.[3] For the recently discovered outer irregular moons (Francisco through Ferdinand) the most accurate orbital data can be generated with the Minor Planet Center's Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service.[20] The irregulars are significantly perturbed by the Sun.[3]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ The mass of Triton is about 2.14قالب:E-sp kg,[10] whereas the combined mass of the Uranian moons is about 0.92قالب:E-sp kg.

- ^ Uranus mass of 8.681قالب:E-sp kg / Mass of Uranian moons of 0.93قالب:E-sp كيلوگرام

- ^ Order refers to the position among other moons with respect to their average distance from Uranus.

- ^ Label refers to the Roman numeral attributed to each moon in order of their discovery.[1]

- ^ Diameters with multiple entries such as "60 × 40 × 34" reflect that the body is not a perfect spheroid and that each of its dimensions have been measured well enough. The diameters and dimensions of Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, and Oberon were taken from Thomas, 1988.[11] The diameter of Titania is from Widemann, 2009.[14] The dimensions and radii of the inner moons are from Karkoschka, 2001,[15] except for Cupid and Mab, which were taken from Showalter, 2006.[16] The radii of outer moons except Sycorax and Caliban were taken from Sheppard, 2005.[3] The radii of Sycorax and Caliban are from Farkas-Takács et al., 2017.[17]

- ^ Masses of Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon were taken from Jacobson, 1992.[18] Masses of all other moons were calculated assuming a density of 1.3 g/cm3 and using given radii.

- ^ Negative orbital periods indicate a retrograde orbit around Uranus (opposite to the planet's rotation).

- ^ Inclination measures the angle between the moon's orbital plane and the plane defined by Uranus's equator.

- ^ أ ب Detected in 2001, published in 2003.

المراجع

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. July 21, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ أ ب Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Beebe, A.; Bliss, D.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A.; Briggs, G. A.; Brown, R. H.; Collins, S. A. (4 July 1986). "Voyager 2 in the Uranian System: Imaging Science Results". Science. 233 (4759): 43–64. Bibcode:1986Sci...233...43S. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.43. PMID 17812889. S2CID 5895824.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D.; Kleyna, J. (2005). "An Ultradeep Survey for Irregular Satellites of Uranus: Limits to Completeness". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (1): 518–525. arXiv:astro-ph/0410059. Bibcode:2005AJ....129..518S. doi:10.1086/426329. S2CID 18688556.

- ^ Herschel, John (1834). "On the Satellites of Uranus". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 3 (5): 35–36. Bibcode:1834MNRAS...3...35H. doi:10.1093/mnras/3.5.35.

- ^ Lassell, W. (1851). "On the interior satellites of Uranus". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 12: 15–17. Bibcode:1851MNRAS..12...15L. doi:10.1093/mnras/12.1.15.

- ^ Lassell, W. (1848). "Observations of Satellites of Uranus". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8 (3): 43–44. Bibcode:1848MNRAS...8...43L. doi:10.1093/mnras/8.3.43.

- ^ Lassell, William (December 1851). "Letter from William Lassell, Esq., to the Editor". Astronomical Journal. 2 (33): 70. Bibcode:1851AJ......2...70L. doi:10.1086/100198.

- ^ أ ب Kuiper, G. P. (1949). "The Fifth Satellite of Uranus". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 61 (360): 129. Bibcode:1949PASP...61..129K. doi:10.1086/126146.

- ^ William Lassell (1852). "Beobachtungen der Uranus-Satelliten". Astronomische Nachrichten. 34: 325. Bibcode:1852AN.....34..325.

- ^ Tyler, G.L.; Sweetnam, D.L.; et al. (1989). "Voyager radio science observations of Neptune and Triton". Science. 246 (4936): 1466–73. Bibcode:1989Sci...246.1466T. doi:10.1126/science.246.4936.1466. PMID 17756001. S2CID 39920233.

- ^ أ ب Thomas, P. C. (1988). "Radii, shapes, and topography of the satellites of Uranus from limb coordinates". Icarus. 73 (3): 427–441. Bibcode:1988Icar...73..427T. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90054-1.

- ^ Brozović, Marina; Jacobson, Robert A. (April 2009). "The Orbits of the Outer Uranian Satellites". The Astronomical Journal. 137 (4): 3834–3842. Bibcode:2009AJ....137.3834B. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/4/3834.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Williams, Dr. David R. (2007-11-23). "Uranian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). Archived from the original on 2010-01-05. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ^ Widemann, T.; Sicardy, B.; Dusser, R.; Martinez, C.; Beisker, W.; Bredner, E.; Dunham, D.; Maley, P.; Lellouch, E.; Arlot, J. -E.; Berthier, J.; Colas, F.; Hubbard, W. B.; Hill, R.; Lecacheux, J.; Lecampion, J. -F.; Pau, S.; Rapaport, M.; Roques, F.; Thuillot, W.; Hills, C. R.; Elliott, A. J.; Miles, R.; Platt, T.; Cremaschini, C.; Dubreuil, P.; Cavadore, C.; Demeautis, C.; Henriquet, P.; et al. (February 2009). "Titania's radius and an upper limit on its atmosphere from the September 8, 2001 stellar occultation" (PDF). Icarus. 199 (2): 458–476. Bibcode:2009Icar..199..458W. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.09.011. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Karkoschka, Erich (2001). "Voyager's Eleventh Discovery of a Satellite of Uranus and Photometry and the First Size Measurements of Nine Satellites". Icarus. 151 (1): 69–77. Bibcode:2001Icar..151...69K. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6597.

- ^ Showalter, Mark R.; Lissauer, Jack J. (2006-02-17). "The Second Ring-Moon System of Uranus: Discovery and Dynamics". Science. 311 (5763): 973–977. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..973S. doi:10.1126/science.1122882. PMID 16373533. S2CID 13240973.

- ^

Farkas-Takács, A.; Kiss, Cs.; Pál, A.; Molnár, L.; Szabó, Gy. M.; Hanyecz, O.; et al. (September 2017). "Properties of the Irregular Satellite System around Uranus Inferred from K2, Herschel, and Spitzer Observations". The Astronomical Journal. 154 (3): 13. arXiv:1706.06837. Bibcode:2017AJ....154..119F. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa8365. S2CID 118869078. 119.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Jacobson, R. A.; Campbell, J. K.; Taylor, A. H.; Synnott, S. P. (June 1992). "The masses of Uranus and its major satellites from Voyager tracking data and earth-based Uranian satellite data". The Astronomical Journal. 103 (6): 2068–2078. Bibcode:1992AJ....103.2068J. doi:10.1086/116211.

- ^ Jacobson, R. A. (1998). "The Orbits of the Inner Uranian Satellites From Hubble Space Telescope and Voyager 2 Observations". The Astronomical Journal. 115 (3): 1195–1199. Bibcode:1998AJ....115.1195J. doi:10.1086/300263.

- ^ "Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service". IAU: Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Karkoschka2001, Hubble" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "IAUC 7171" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "IAUC 8217" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Denning1881" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Hughes1994" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "DumasSmithTerrile2003" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Esposito2002" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Pappalardo1997" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Tittemore Wisdom 1990" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Tittemore 1990" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Grundy Young et al. 2006" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Duncan Lissauer 1997" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

<ref> ذو الاسم "Mousis 2004" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.وصلات خارجية

- Scott S. Sheppard: Uranus Moons

- Simulation Showing the location of Uranus's Moons

- "Uranus: Moons". NASA's Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- "NASA's Hubble Discovers New Rings and Moons Around Uranus". Space Telescope Science Institute. 22 December 2005. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature—Uranus (USGS)