سيارة كهربائية

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الطاقة المستدامة |

|---|

|

| حفظ الطاقة |

| الطاقة المتجددة |

| نقل مستدام |

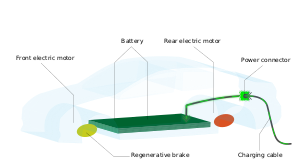

السيارة الكهربائية (electric car)، أو المركبة الكهربائية (electric vehicle، اختصاراً EV)، هي سيارة ركاب تعمل بواسطة محرك جر كهربائي، مستخدمة فقط الطاقة المخزنة في البطاريات المثبتة. مقارنة بمركبات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي التقليدية، فالسيارات الكهربائية أكثر هدوءًا، وأكثر استجابة، وتتمتع بكفاءة أكبر لتحويل الطاقة ولا تحتوي على انبعاثات العادم وانبعاثات مركبات إجمالية أقل[1] (إلا أن محطة الطاقة التي تُولد الكهرباء قد تنتج انبعاثاتها الخاصة). يشير مصطلح "السيارة الكهربائية" عادةً إلى المركبات الكهربائية القابلة للتوصيل، وعادةً ما تكون المركبات الكهربائية التي تعمل بالبطارية (BEV)، لكنها على النطاق الأوسع قد تشمل أيضًا المركبات الكهربائية الهجينة القابلة للتوصيل (PHEV)، السيارات الكهربائية موسعة النطاق (REEV) والمركابات الكهربائية التي تعمل بخلايا الوقود (FCEV).

تحتاج بطارية المركبة الكهربائية عادةً إلى توصيل مصدر كهربائية رئيسي من أجل إعادة الشحن لزيادة نطاق القيادة]. يمكن إعادة شحن السيارة الكهربائية في أنواع مختلفة من محطات الشحن؛ يمكن تركيب محطات الشحن هذه في المنازل الخاصة، ومرآب السيارات، والمناطق العامة.[2]

هناك أيضًا بحث وتطوير في تقنيات أخرى مثل تبديل البطاريات والشحن بالحث. نظرًا لأن البنى التحتية لإعادة الشحن (خاصة تلك التي تحتوي على شواحن سريعة) لا تزال في مهدها نسبيًا، فإن قلق النطاق وتكلفة الوقت من العوائق النفسية المتكررة التي تواجه السيارات الكهربائية أثناء قرارات الشراء من قبل المستهلك.

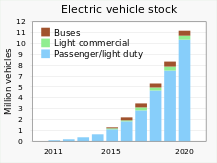

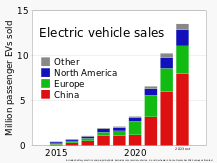

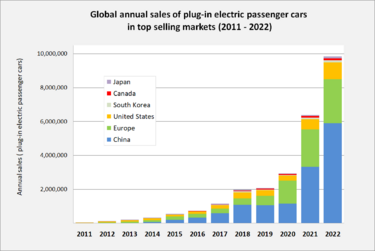

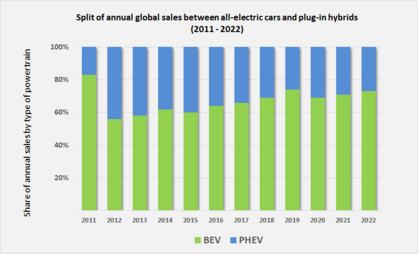

عالمياً، بيع 10 مليون سيارة كهربائية قابلة للتوصيل عام 2022، أي ما مجموعه 14% من مبيعات السيارات الجديدة،[3] أكثر عن 9% عام 2021.أنشأت العديد من البلدان حوافز حكومية للسيارات الكهربائية، وإعفاءات ضريبية، وإعانات، وحوافز غير نقدية أخرى، في حين سنت العديد من البلدان تشريعات التخلص التدريجي من مبيعات سيارات الوقود الأحفوري،[4][5] للحد من تلوث الهواء والتخفيف من آثار تغير المناخ.[6][7] وكان من المتوقع أن تمثل السيارات الكهربائية ما يقرب من خمس المبيعات العالمية للسيارات عام 2023، بحسب وكالة الطاقة الدولية.[8]

تمتلك الصين حاليًا أكبر مخزون من المركبات الكهربائية في العالم، مع مبيعات تراكمية بلغت 5.5 مليون وحدة حتى ديسمبر 2020،[9] على الرغم من أن هذه الأرقام تشمل أيضًا المركبات التجارية الثقيلة مثل الحافلات وشاحنات القمامة ومركبات الصرف الصحي، ولا تمثل سوى المركبات المصنعة في الصين.[10][11][12][13][14][15] في الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي، اعتبارًا من عام 2020، تكون التكلفة الإجمالية لملكية المركبات الكهربائية الحديثة أرخص من تكلفة سيارات محركات الاحتراق الداخلي المكافئة، وذلك بسبب انخفاض تكاليف الصيانة والتزود بالوقود.[16][17]

عام 2023، أصبحت تسلا مودل واي السيارة الأكثر مبيعًا في العالم.[18] وفي أوائل 2020 أصبحت تسلا مودل 3 السيارة الكهربائية الأكثر مبيعاً في العالم على الإطلاق،[19] وفي يونيو 2021 أصبحت أول سيارة كهربائية تجاوزت مبيعاتها عالمياً 1 مليون سيارة.[20] جنبًا إلى جنب مع تقنيات السيارات الناشئة الأخرى مثل القيادة الذاتية والمركبات المتصلة والتنقل المشترك، تشكل السيارات الكهربائية رؤية مستقبلية للتنقل تسمى التنقل المستقل والمتصل والكهربائي والمشترك (ACES).[21]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

المصطلح

عادة ما يشير مصطلح "السيارة الكهربائية" على وجه التحديد إلى المركبات الكهربائية التي تعمل بالبطارية (BEVs) أو السيارات الكهربائية بصفة عامة، وهو نوع من المركبات الكهربائية (EV) التي تحتوي على حزمة بطاريات قابلة للشحن يمكن توصيلها وشحنها من الشبكة الكهربائية، والكهرباء المخزنة في المركبة هي مصدر الطاقة "الوحيد" الذي يوفر الدفع للعجلات. يشير المصطلح بشكل عام إلى السيارات ذات القدرة على السير على الطرق السريعة، لكن هناك أيضًا مركبات كهربائية منخفضة السرعة ذات قيود من حيث الوزن والقوة والسرعة القصوى المسموح لها بالسير على الطرق العامة. تُصنف الأخيرة كمركبات كهربائية للضواحي (NEVs) في الولايات المتحدة،[22] وكدراجة رباعية بمحرك في أوروپا.[23]

التاريخ

التطورات المبكرة

غالباً ما يُنسب الفضل إلى روبرت أندرسون في اختراع أول سيارة كهربائية في وقت ما بين عامي 1832 و1839.[24]

ظهرت السيارات الكهربائية التجريبية التالية خلال ثمانينيات القرن التاسع عشر:

- عام 1881، قدم گوستاڤ تروڤي سيارة كهربائية يقودها محرك سيمنز محسن في المعرض الدولي للكهرباء في پاريس.[25]

- عام 1884، أي قبل أكثر من 20 عامًا من ظهور فورد مودل تي، قام توماس پاركر ببناء سيارة كهربائية في ولڤرهامتون باستخدام بطارياته القابلة اللشحن عالية السعة والمصممة خصيصًا له، على الرغم من أن التوثيق الوحيد هو صورة فوتوغرافية تعود لعام 1895.[26][27][28]

- عام 1888، صمم الألماني أندرياس فلوكن السيارة فولكن إلكتروڤاگن، والتي يعتبرها البعض أول سيارة كهربائية "حقيقية".[29][30][31]

- عام 1890، قدم أندرو موريسون أول سيارة كهربائية في الولايات المتحدة.[32]

كانت الكهرباء من بين الطرق المفضلة لدفع السيارات في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر وأوائل القرن العشرين، مما يوفر مستوى من الراحة وسهولة التشغيل لم يكن من الممكن تحقيقه بواسطة السيارات التي تعمل بالگازولين في ذلك الوقت.[33] بلغ أسطول المركبات الكهربائية ذروته بنحو 30.000 مركبة في مطلع القرن العشرين.[34]

عام 1897، استخدمت السيارات الكهربائية لأول مرة تجاريًا باسم سيارات الأجرة في بريطانيا والولايات المتحدة. في لندن، كانت سيارة أجرة والتر برسي الكهربائية أول سيارات أجرة ذاتية الدفع في الوقت الذي كانت فيه سيارات الأجرة تجرها الخيول.[35] في مدينة نيويورك، كان هناك أسطول مكون من اثنتي عشرة سيارة هانسوم وبروگهام واحد، استنادًا إلى تصميم إلكتروبات، كجزء من مشروع ممول جزئيًا من شركة بطاريات التخزين الكهربائية في فيلادلفيا.[36] خلال القرن العشرين، كانت الشركات المصنعة الرئيسية للمركبات الكهربائية في الولايات المتحدة تشمل أنتوني إلكتريك، وبيكر، وكلومبيا، وأندرسون، وإديسون، وريكر، وملبورن، بيلي إلكتريك، وديترويت إلكتريك. وكانت مركباتهم الكهربائية أكثر هدوءًا من تلك التي تعمل بالگازولين، ولم تكن تتطلب تغيير ناقل الحركة.[37][38]

في القرن التاسع عشر سجلت ست سيارات كهربائية السجل القياسي للسرعة على الأرض.[39] وكان آخرها سيارة لا جاميس كونتي ذات الشكل الصاروخي بقيادة كاميل جناتزي، والتي كسرت حاجز سرعة 100 كم/س بوصولها إلى سرعة 105.88 كم/س عام 1899.

ظلت السيارات الكهربائية شائعة حتى التقدم في شهدته سيارات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي (ICE) والإنتاج الضخم للمركبات التي تعمل بالگازولين والديزل الأرخص ثمناً، وخاصةً فورد مودل تي، الذي أدى إلى تراجع السيارات الكهربائية.[32] إن سرعة وقت تزود سيارات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي بالوقود وتكاليف إنتاجها الأرخص جعلتها أكثر شعبية. ومع ذلك، جاءت اللحظة الحاسمة مع طرح بمحرك بدء التشغيل الكهربائي عام 1912[40] الذي حلت محل الطرق الأخرى، التي غالبًا ما تكون شاقة، لبدء تشغيل محرك الاحتراق الداخلي، مثل التدوير اليدوي.

مركبة گوستاڤ تروڤي الكهربائية الشخصية (1881)، أول سيارة كهربائية بالكامل تُطرح علنًا في العالم مدعومة بمحرك سيمنز محسّن.

أول ترولي باص بناه ڤرنر فون سيمنز، برلين 1882.

فولكن إلكتروڤاگن (1888)، أول سيارة كهربائية بأربع عجلات في العالم.[41]

سيارة كهربائية مبكرة بناها توماس پاركر، صورة من عام 1895.[42]

"لا جاميس كونتي"، 1899.

جنرال موتورز إي ڤي 1، إحدى السيارات التي طُرحت بموجب تفويض مجلس كاليفورنيا للموارد الجوية (CARB)، يبلغ نطاقها 260 كم، وتعمل ببطارية ببطاريات NiMH، 1999.

تسلا رودستر، ساعدت في استلهام الجيل الحديث من المركبات الكهربائية.

السيارات الكهربائية الحديثة

في أوائل التسعينيات، بدأ مجلس كاليفورنيا للموارد الجوية (CARB) حملة من أجل المزيد من المركبات ذات الكفاءة في استهلاك الوقود والانبعاثات المنخفضة، بهدف نهائي يتمثل في الانتقال إلى مركبات خالية من الانبعاثات مثل المركبات الكهربائية.[43][44] استجابة لذلك، طور مصنعو السيارات نماذج كهربائية. سُحبت هذه السيارات المبكرة في نهاية المطاف من السوق الأمريكية، بسبب حملة واسعة النطاق قامت بها شركات صناعة السيارات الأمريكية لتشويه سمعة فكرة السيارات الكهربائية.[45]

عام 2004 بدأت شركة تسلا لصناعة السيارات الكهربائية في كاليفورنيا بتطوير ما سيصبح تسلا رودستر، وتم تسليمها لأول مرة للعملاء عام 2008. وكانت رودستر أول سيارة كهربائية بالكامل يمكنها السير على الطرق السريعة بشكل قانوني، وكانت تستخدم خلايا بطارية ليثيوم-أيون، وهي أول سيارة كهربائية بالكامل تسير مسافة 320 كيلومتراً في الشحنة.[46]

بتر پالاس، وهي شركة مدعومة بالمخاطر مقرها پالو ألتو، كاليفورنيا، لكنها تدار من إسرائيل، قامت بتطوير وبيع شحن البطاريات وخدمات تبديل البطاريات للسيارات الكهربائية. أُطلقت الشركة في 29 أكتوبر 2007 وأعلنت عن نشر شبكات المركبات الكهربائية في إسرائيل، الدنمارك وهاواي عامي 2008 و2009. وخططت الشركة لنشر البنية التحتية لكل دولة على حدة. في يناير 2008، أعلنت شركة بتر پالاس عن مذكرة تفاهم مع رينو-نيسان لبناء أول نموذج في العالم لمشغل شبكة إعادة الشحن الكهربائي (ERGO) في إسرائيل. وبموجب الاتفاقية، ستقوم شركة بتر پالاس ببناء شبكة إعادة الشحن الكهربائية وستقوم رينو-نيسان بتوفير المركبات الكهربائية. في مايو 2013 أعلنت شركة بتر پالاس إفلاسها في إسرائيل. وكانت الصعوبات المالية التي واجهتها الشركة ناجمة عن سوء الإدارة، والجهود المهدرة لإنشاء موطئ قدم وتشغيل pilots في العديد من البلدان، والاستثمار الكبير المطلوب لتطوير البنية التحتية للشحن والتداول، واختراق السوق بشكل أقل مما كان متوقعاً في الأصل.[47]

كانت ميتسوبيشي آي-مي، التي أُطلقت في اليابان عام 2009، أول سيارة كهربائية مقننة للسير على الطرق السريعة تُنتج بالجملة،[48] وكذلك أول سيارة كهربائية بالكامل تبيع أكثر من 10.000 وحدة في الأشهر التالية، نيسان ليف، التي أُطلقت عام 2010، تفوقت على ميتسوبيشي آي-مي كأفضل السيارات الكهربائية مبيعاً في ذلك الوقت.[49]

بدءاً من عام 2008، حدثت نهضة في تصنيع السيارات الكهربائية بسبب التقدم في البطاريات، والرغبة في تقليل انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة وتحسين جودة الهواء في المناطق الحضرية.[50] خلال عقد 2010، شهدت صناعة المركبات الكهربائية في الصين توسعاً سريعاً بدعم من الحكومة الصينية.[51] ورفعت العديد من شركات صناعة السيارات أسعار سياراتها الكهربائية تحسباً لتعديلات الدعم، بما في ذلك تسلا وفولكسڤاگن ومجموعة جي إيه سي ومقرها گوانگژو، والتي تعتبر فيات وهوندا وإيسوزو وميتسوبيشي وتويوتا شركاء أجانب.[52]

في يوليو 2019، منحت مجلة موتور ترند ومقرها الولايات المتحدة سيارة تسلا مودل S الكهربائية بالكامل لقب "السيارة المثالية لهذا العام".[53]

في مارس 2020، تجاوزت تسلا مودل 3 سيارة نيسان ليف لتصبح السيارة الكهربائية الأكثر مبيعًا في العالم على الإطلاق، مع تسليم أكثر من 500.000 وحدة؛[19] وصلت لحجم مبيعات عالمي بنحو 1 مليون سيارة في يونيو 2021.[20]

في الربع الثالث من عام 2021، أفاد التحالف من أجل ابتكار السيارات أن مبيعات المركبات الكهربائية وصلت إلى ستة بالمائة من جميع مبيعات السيارات الخفيفة في الولايات المتحدة، وهو أعلى حجم لمبيعات المركبات الكهربائية تم تسجيله على الإطلاق بنحو 187.000 مركبة. وكانت هذه زيادة في المبيعات بنسبة 11%، مقابل زيادة بنسبة 1.3% في الوحدات التي تعمل بالگازولين والديزل. وأشار التقرير إلى أن كاليفورنيا كانت الرائدة في الولايات المتحدة في مجال المركبات الكهربائية بنسبة 40% تقريبًا من مشتريات الولايات المتحدة، تليها فلوريدا – 6%، وتكساس – 5%، ونيويورك 4.4%.[56]

قامت شركات الكهرباء من الشرق الأوسط بتصميم السيارات الكهربائية. قامت مايز موتورز العمانية بتطوير سيارة مايز آي إي 1 والتي كان من المتوقع أن يبدأ إنتاجها عام 2023. السيارة المبنية من ألياف الكربون، كان نطاقها 560 كم تقريباً ويمكنها التحرك من 0–130 كم/س في غضون 4 ثواني.[57] في تركيا، شرعت شركة توگ ببدء إنتاج مركباتها الكهربائية. ستستخدم تلك المركبات بطاريات تُنتج عبر شركة محاصة مع شركة فاراسيس إنرجي الصينية.[58]

التنافس الأمريكي-الصيني

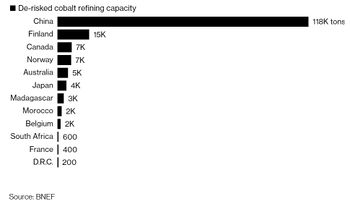

الحكومة الأمريكية تستحوذ على حصة في شركة لانتاج فلزات البطاريات، في تحرك لتقليل الاعتماد على الصين في المواد الأساسية لانتاج السيارات الكهربائية.[59]

حصلت شركة تكمت المحدودة على استثمار قدره 25 مليون دولار من المؤسسة الدولية لتمويل التنمية الأمريكية للمساعدة في تطوير منجم برازيلي للنيكل والكوبالت. يعتبر الكوبالت مكوناً هاماً في كاثودات معظم بطاريات السيارات الكهربائية، كما أن قدرته على التكرير تخضع إلى حد كبير لسيطرة الصين.

قال آدم بوهلر، الرئيس التنفيذي للوكالة الحكومية، في البيان الصادر عن تكمت: "الاستثمارات في المواد الحيوية للتكنولوجيا المتقدمة تدعم تنمية وتقدم السياسة الخارجية للولايات المتحدة".

هذه الخطوة هي مثال آخر على جهود الولايات المتحدة لتقليل الاعتماد على أكبر منافسيها الجيوسياسين للمواد الرئيسية وتأتي بعد أيام من توقيع الرئيس دونالد ترمپ على أمر تنفيذي لتوسيع الإنتاج المحلي من الفلزات الأرضية النادرة - قطاع آخر تهيمن عليه الصين. هذه المعادن ضرورية للمغناطيسات في مجموعة واسعة من المنتجات بما في ذلك السيارات الكهربائية.

تتصمن استثمارات تكمت مصانع إعادة تدوير بطاريات الليثيوم-أيون في كندا والولايات المتحدة، منتاجم القصدير والتنگستن في رواندا، ومرفق ڤانديوم أمريكي. تقع معظم الفلزات المستهدفة من قبل الشركة تحت سيطرة الصين في مرحلة ما من سلسلة التوريد العالمي.

الجوانب الاقتصادية

تكلفة التصنيع

تعتبر البطارية هي أكثر الأجزاء تكلفة في تصنيع السيارات الكهربائية. انخفض السعر من 605 يورو لكل كم/س عام 2010، إلى 170 يورو عام 2017، إلى 100 يورو عام 2019.[60][61] عند تصميم سيارة كهربائية، قد يجد المصنعون أنه بالنسبة للإنتاج المنخفض، فإن تحويل المنصات الحالية قد يكون أرخص، حيث أن تكلفة التطوير أقل؛ ومع ذلك، بالنسبة للإنتاج العالي، قد يكون من الأفضل استخدام منصة مخصصة لتحسين التصميم والتكلفة.[62]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التكلفة الإجمالية للملكية

في الاتحاد الأوروپي والولايات المتحدة، لكن ليس في الصين بعد، تعد التكلفة الإجمالية لملكية السيارات الكهربائية الحديثة أرخص من مثيلاتها من السيارات التي تعمل بالگازولين، وذلك بسبب انخفاض تكاليف الشحن والصيانة.[16][17][63]

وجد تحليل تقارير المستهلك لعام 2024 لنحو 29 علامة تجارية للسيارات أن تسلا كانت الأقل تكلفة في الصيانة؛ وكانت تسلا هي العلامة التجارية الوحيدة التي تعمل بالكهرباء بالكامل.[64]

كلما زادت المسافة المقطوعة سنويًا، زاد احتمال أن تكون التكلفة الإجمالية للملكية للسيارة الكهربائية أقل من سيارة محرك الاحتراق الداخلي المماثلة.[65]

تختلف مسافة نقطعة التعادل حسب البلد اعتمادًا على الضرائب والدعم والتكاليف المختلفة للطاقة. في بعض البلدان، قد تختلف المقارنة حسب المدينة، حيث قد يكون لنوع السيارة رسوم مختلفة لدخول مدن مختلفة؛ على سبيل المثال، في إنگلترة، تقوم لندن بفرض رسوم على سيارات محركات الاحتراق الداخلي أكثر مما تفعله برمنگهام.[66]

تكلفة الشراء

أسست العديد من الحكومات الوطنية والمحلية حوافز المركبات الكهربائية لتقليل سعر شراء السيارات الكهربائية وغيرها من المكونات الإضافية.[67][68][69][70]

اعتباراً من عام 2020، كان تكلفة بطارية السيارة الكهربائية يمثل أكثر من ربع التكلفة الإجمالية للسيارة.[71] من المتوقع أن تنخفض أسعار الشراء إلى أقل من أسعار سيارات محركات الاحتراق الداخلي الجديدة عندما تنخفض تكاليف البطارية إلى أقل من 100 دولار لكل ك.و./س، ومن المتوقع أن يكون ذلك في منتصف عقد 2020.[72][73]

يعتبر التأجير أو الاشتراكات أمرًا شائعًا في بعض البلدان،[74][75] اعتمادا إلى حد ما على الضرائب الوطنية والدعم،[76]ونهاية تأجير السيارات تعمل على توسيع السوق المستعملة.[77]

في تقرير يونيو 2022 الصادر عن ألكسپارتنرز، ارتفعت تكلفة المواد الخام للسيارة الكهربائية المتوسطة من 3381 دولارًا في مارس 2020 إلى 8255 دولارًا في مايو 2022. وتُعزى الزيادة في التكلفة بشكل أساسي إلى الليثيوم والنيكل والكوبالت.[78]

تكلفة التشغيل

تكلف الكهرباء دائمًا أقل من تكلفة الگازولين لكل كيلومتر يتم قطعه، لكن غالبًا ما يختلف سعر الكهرباء اعتمادًا على المكان والوقت الذي يتم فيه شحن السيارة.[79][80] يتأثر توفير التكاليف أيضًا بسعر الگازولين الذي يمكن أن يختلف حسب الموقع.[81]

الجوانب البيئية

تتمتع السيارات الكهربائية بالعديد من الفوائد عند استبدال سيارات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي، بما في ذلك تقليل تلوث الهواء المحلي بشكل كبير، حيث أنها لا تنبعث منها ملوثات العادم مثل المركبات العضوية المتطايرة، الهيدروكربونات، أول أكسيد الكربون، الأوزون، الرصاص، ومختلف أكاسيد النيتروجين.[84] على غرار مركبات محركات الاحتراق الداخلي، تنبعث من السيارات الكهربائية جزيئات ناجمة عن تآكل الإطارات والفرامل[85] التي قد تكون ضارة بالصحة،[86] على الرغم من أن الكبح المتجدد في السيارات الكهربائية يعني غبارًا أقل في الفرامل.[87] هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الأبحاث حول الجسيمات غير العادمة.[88] يؤدي الحصول على الوقود الأحفوري (من بئر النفط إلى خزان الگازولين) إلى مزيد من الضرر بالإضافة إلى استخدام الموارد أثناء عمليات الاستخراج والتكرير.

اعتمادًا على عملية الإنتاج ومصدر الكهرباء اللازم لشحن المركبة، قد تنتقل الانبعاثات جزئيًا من المدن إلى المصانع التي تولد الكهرباء وتنتج المركبة بالإضافة إلى انتقال المواد.[43] تعتمد كمية ثاني أكسيد الكربون المنبعثة على الانبعاثات من مصدر الكهرباء وكفاءة المركبة. بالنسبة إلى الكهرباء من الشبكة، تختلف انبعاثات دورة الحياة وفقًا لنسبة الطاقة المولدة بالفحم، لكنها تكون دائمًا أقل من سيارات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي.[89]

تشير التقديرات إلى أنه تكلفة تركيب البنية التحتية للشحن ستسترد من خلال توفير التكاليف الصحية في أقل من ثلاث سنوات.[90] وفقًا لدراسة أجريت عام 2020، فإن تحقيق التوازن بين العرض والطلب على الليثيوم لبقية القرن سيتطلب أنظمة إعادة تدوير جيدة، وتكامل المركبات مع الشبكة، وانخفاض كثافة الليثيوم في وسائل النقل.[91]

أثار بعض النشطاء والصحفيين مخاوف بشأن النقص الملحوظ في تأثير السيارات الكهربائية على حل أزمة تغير المناخ[92] مقارنة بالطرق الأخرى الأقل شهرة.[93] وقد تركزت هذه المخاوف إلى حد كبير حول وجود أشكال نقل أقل كثافة للكربون وأكثر كفاءة مثل التنقل النشط،[94] النقل الجماعي والدراجات البخارية الإلكترونية واستمرار النظام المصمم للسيارات أولاً.[95]

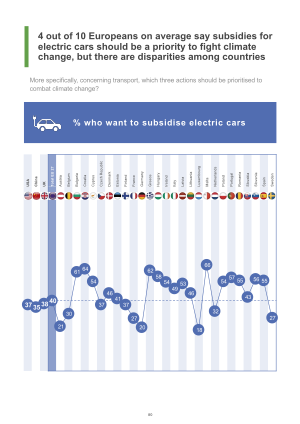

الرأي العام

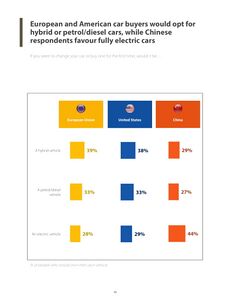

وجد استطلاع عام 2022 أن 33% من مشتري السيارات في أوروپا سيختارون سيارة تعمل بالگازولين أو الديزل عند شراء سيارة جديدة. ذكر 67% من المشاركين اختيار النسخة الهجينة أو الكهربائية.[97][98] وبشكل أكثر تحديدًا، وجدت أن السيارات الكهربائية مفضلة لدى 28% فقط من الأوروپيين، مما يجعلها أقل أنواع السيارات تفضيلاً. يميل 39% من الأوروپيين إلى تفضيل المركبات الهجينة، بينما يفضل 33% المركبات التي تعمل بالگازولين أو الديزل.[97][99]

من ناحية أخرى، فإن 44% من مشتري السيارات الصينيين هم الأكثر احتمالاً لشراء سيارة كهربائية، في حين أن 38% من الأمريكيين يفضلون السيارات الهجينة، و33% يفضلون سيارات الگازولين أو الديزل، بينما يفضل 29% فقط السيارات الكهربائية.[97][100]

بالنسبة إلى للاتحاد الأوروپي على وجه التحديد، من المرجح أن يشتري 47% من مشتري السيارات الذين تزيد أعمارهم عن 65 عامًا سيارة هجينة، في حين أن 31% من المشاركين الأصغر سنًا لا يعتبرون المركبات الهجينة خيارًا جيدًا. 35% يفضلون سيارة تعمل بالگازولين أو الديزل، و24% يفضلون السيارة الكهربائية بدلاً من الهجينة.[97][101]

في الاتحاد الأوروپي، 13% فقط من إجمالي السكان لا يخططون لامتلاك سيارة على الإطلاق.[97]

الأداء

تصميم التسارع ونظام الدفع

يمكن للمحركات الكهربائية توفير نسبة مرتفعة للقدرة إلى الوزن. يمكن تصميم البطاريات لتزويد التيار الكهربائي اللازم لدعم هذه المحركات. تتمتع المحركات الكهربائية بمنحنى عزم دوران مسطح يصل إلى سرعة الصفر. من أجل البساطة والموثوقية، تستخدم معظم السيارات الكهربائية علب سرعة ذات نسبة ثابتة ولا تحتوي على قابض.

تتمتع العديد من السيارات الكهربائية بتسارع أكبر من سيارات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي المتوسطة، ويرجع ذلك إلى حد كبير إلى انخفاض خسائر الاحتكاك في نظام نقل الحركة وعزم الدوران المتوفر بسرعة أكبر للمحرك الكهربائي.[102] ومع ذلك، قد يكون لسيارات الطاقة الجديدة تسارع منخفض بسبب محركاتها الضعيفة نسبيًا.

يمكن للسيارات الكهربائية أيضًا استخدام محرك في كل محور عجلة أو بجوار العجلات؛ هذا أمر نادر لكن يُزعم أنه أكثر أمانًا.[103]

المركبات الكهربائية التي تفتقر إلى محور، ترس السرعة، أو علبة السرعة يمكن أن يكون لها قصور ذاتي أقل في نظام نقل الحركة. تحتوي بعض السيارات الكهربائية المجهزة محرك التيار المستمر على علبة سرعة يدوية بسرعتين بسيطتين لتحسين السرعة القصوى.[104]

يُزعم أن السيارة الكهربائية الخارقة ريماك كونسپت ون يمكن أن تنطلق من سرعة 0-97 كم/ساعة في غضون 2.5 ثانية. تدعي تسلا أن سيارة تسلا رودستر القادمة ستنطلق من سرعة 0-97 كم/ساعة في غضون 1.9 ثانية.[105]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

كفاءة الطاقة

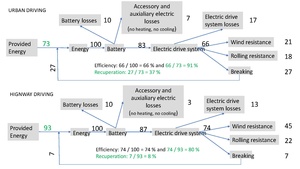

تمتلك محركات الاحتراق الداخلي حدود الديناميكا الحرارية على الكفاءة، ويتم التعبير عنها بجزء صغير من الطاقة المستخدمة لدفع السيارة مقارنة بالطاقة الناتجة عن حرق الوقود. تستخدم محركات الگازولين بفعالية 15% فقط من محتوى طاقة الوقود لتحريك السيارة أو لتشغيل ملحقاتها؛ يمكن أن تصل كفاءة محركات الديزل على متن الطائرة إلى 20%؛ تقوم المركبات الكهربائية بتحويل أكثر من 77% من الطاقة الكهربائية من الشبكة إلى الطاقة الموجودة على العجلات.[106][107][108]

تعد المحركات الكهربائية أكثر كفاءة من محركات الاحتراق الداخلي في تحويل الطاقة المخزنة إلى قيادة المركبة. ومع ذلك، فهي ليست فعالة على قدم المساواة في جميع السرعات. وللسماح بذلك، تحتوي بعض المركبات ذات المحركات الكهربائية المزدوجة على محرك كهربائي واحد مع ترس محسّن لسرعات المدن ومحرك كهربائي آخر مع ترس محسّن لسرعات الطرق السريعة. تختار الإلكترونيات المحرك الذي يتمتع بأفضل كفاءة للسرعة والتسارع الحاليين.[109] الكبح المتجدد، وهو الأكثر شيوعًا في المركبات الكهربائية، يمكن أن يستعيد ما يصل إلى خمس الطاقة المفقودة عادة أثناء الكبح.[43][107]

تدفئة وتبريد المقصورة

تستغل السيارات التي تعمل بالاحتراق الحرارة المهدرة من المحرك لتوفير تدفئة للمقصورة، لكن هذا الخيار غير متوفر في السيارات الكهربائية. بينما يمكن توفير التدفئة باستخدام سخان مقاوم كهربائي، يمكن الحصول على كفاءة أعلى وتبريد متكامل باستخدام مضخة حرارية قابلة للعكس، كما هو الحال في نيسان ليف.[110] كما يعتبر تبريد وصلة م.د.إ.[111] أداة جذابة أيضاً بسبب بساطتها، حيث استخدم هذا النظام، على سبيل المثال، في سيارة تسلا رودستر 2008.

لتجنب استخدام جزء من طاقة البطارية للتدفئة وبالتالي تقليل النطاق، تسمح بعض الطرازات بتدفئة المقصورة أثناء شحن السيارة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن تسخين سيارات نيسان ليف، وميتسوبيشي آي-مي، ورينو زوي، وتسلا مسبقًا أثناء شحن السيارة.[112][113][114]

تستخدم بعض السيارات الكهربائية (على سبيل المثال، ستروين برلينگو إلكتريك) نظام تدفئة إضافي (على سبيل المثال، وحدات تعمل بالگازولين تم تصنيعها بواسطة وباستو أو إبرسپاتشر) لكنها تضحي ببيانات الاعتماد "الخضراء" و"الانبعاثات الصفرية". يمكن تعزيز تبريد المقصورة باستخدام بطارية خارجية تعمل بالطاقة الشمسية ومراوح أو مبردات يو إس بي، أو عن طريق السماح تلقائيًا للهواء الخارجي بالتدفق عبر السيارة عند ركنها؛ يتضمن طرازان من تويوتا پريوس 2010 هذه الميزة كخيار.[115]

السلامة

يتم التعامل مع قضايا سلامة المركبات الكهربائية التي تعمل بالبطارية إلى حد كبير وفقًا للمعايير الدولية آيزو 6469. وتنقسم هذه الوثيقة إلى ثلاثة أجزاء تتناول قضايا محددة:

- تخزين الطاقة الكهربائية على متن المركبة، أي البطارية.[116]

- وسائل السلامة الوظيفية والحماية من الأعطال.[117]

- حماية الأشخاص من المخاطر الكهربائية.[118]

الوزن

عادةً ما يجعل وزن البطاريات نفسها السيارة الكهربائية أثقل من سيارة الگازولين المماثلة. في حالة حدوث تصادم، سيتعرض ركاب المركبات الثقيلة، في المتوسط، لإصابات أقل وأقل خطورة من ركاب المركبات الخفيفة؛ وبالتالي فإن الوزن الإضافي يجلب فوائد السلامة للراكب، بينما يزيد الضرر على المركبات الأخرى.[119] في المتوسط، يؤدي وقوع حادث إلى إصابة ركاب مركبة يبلغ وزنها 900 كجم بنسبة 50% أكثر من ركاب مركبة يبلغ وزنها 3000 1400 كجم.[120] السيارات الأثقل تكون أكثر خطورة على الأشخاص الموجودين خارج السيارة إذا اصطدمت بأحد المشاة أو بمركبة أخرى.[121]

الاستقرار

تعمل البطارية المثبتة على لوح الانزلاق على خفض مركز الجاذبية، مما يزيد من ثبات القيادة، ويقلل من خطر وقوع حادث من خلال فقدان السيطرة.[122] إذا كان هناك محرك منفصل بالقرب من أو في كل عجلة، يُقال أن هذا أكثر أمانًا بسبب التعامل الأفضل.[123]

خطر الحريق

مثل نظيراتها في مركبات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي، يمكن أن تشتعل بطاريات السيارة الكهربائية عقب وقوع حادث أو عطل ميكانيكي.[124] وقعت حدثت حوادث حرائق في المركبات الكهربائية القابلة للتوصيل، وإن كانت أقل بالنسبة لكل مسافة مقطوعة مقارنة بمركبات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي.[125] تم تصميم أنظمة الجهد العالي في بعض السيارات بحيث يتوقف تشغيلها تلقائيًا في حالة انتشار الوسادة الهوائية،[126][127] وفي حالة الفشل، يمكن تدريب رجال الإطفاء على إيقاف تشغيل نظام الجهد العالي يدويًا.[128][129] قد تكون هناك حاجة إلى كمية أكبر من المياه مقارنة بحرائق مركبات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي ويوصى باستخدام كاميرا التصوير الحراري للتحذير من احتمال إعادة اشتعال حرائق البطاريات.[130][131]

عناصر التحكم

اعتبارًا من 2018، كانت معظم السيارات الكهربائية تتمتع بعناصر تحكم في القيادة مماثلة لتلك الموجودة في السيارة ذات نقل الحركة الأوتوماتيكي التقليدي. على الرغم من أن المحرك قد يكون متصلاً بشكل دائم بالعجلات من خلال تروس ذات نسبة ثابتة، وعدم وجود مسقاط التوقف، إلا أن الوضعين "P" و"N" لا يزالان متوفرين غالبًا في المحدد. في هذه الحالة، يتم تعطيل المحرك في الوضع "N" وتوفر مكابح اليد التي يتم تشغيلها كهربائيًا الوضع "P".

في بعض السيارات، يدور المحرك ببطء ليوفر قدرًا صغيرًا من الزحف على شكل "D"، على غرار السيارات ذات ناقل الحركة الأوتوماتيكي التقليدي.[132]

عند تحرير دواسة الوقود في سيارات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي، فقد تتباطأ بواسطة كبح المحرك، اعتمادًا على نوع ناقل الحركة والوضع. عادةً ما تكون المركبات الكهربائية مجهزة كوابح متجددة تعمل على إبطاء السيارة وإعادة شحن البطارية إلى حد ما.[133] تعمل أنظمة الكبح المتجدد أيضًا على تقليل استخدام الكوابح التقليدية (على غرار كبح المحرك في مركبات محركة الاحتراق الداخلي)، مما يقلل من تآكل الكوابح وتكاليف الصيانة.

البطاريات

عادة ما تستخدم البطارايت المعتمدة على الليثيوم-أيون لتمتعها بقدرة مرتفعة وكثافة كبيرة للطاقة.[134] أصبح استخدام البطاريات ذات التركيبات الكيميائية المختلفة على نطاق واسع، مثل فوسفات الليثيوم حديد والتي لا تعتمد على النيكل والكوبالت لذلك يمكن استخدامها لصنع بطاريات أرخص وبالتالي سيارات أرخص.[135]

النطاق

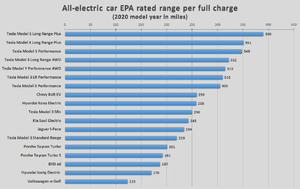

يعتمد مدى السيارة الكهربائية على عدد ونوع البطاريات المستخدمة، (كما هو الحال مع جميع المركبات)، والديناميكا الهوائية، ووزن السيارة ونوعها، ومتطلبات الأداء، والطقس.[137] غالبًا ما يتم تُصنع السيارات التي يتم تسويقها للاستخدام في المدن بشكل أساسي ببطارية قصيرة المدى لإبقائها صغيرة وخفيفة.[138]

معظم السيارات الكهربائية مجهزة بشاشة عرض للنطاق المتوقع. قد يأخذ هذا في الاعتبار كيفية استخدام المركبة وما هي طاقة البطارية. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لأن العوامل يمكن أن تختلف على المسار، فقد يختلف التقدير عن النطاق الفعلي. تتيح الشاشة للسائق اتخاذ خيارات مستنيرة بشأن سرعة القيادة وما إذا كان يجب التوقف عند نقطة الشحن في الطريق. تقدم بعض منظمات المساعدة على الطريق شاحنات شحن لإعادة شحن السيارات الكهربائية في حالة الطوارئ.[139]

الشحن

الموصلات

تستخدم معظم السيارات الكهربائية الاتصال الاسلكي لتوفير الكهرباء لإعادة الشحن. قوابس شحن السيارات الكهربائية ليست عالمية في جميع أنحاء العالم. ومع ذلك، فإن المركبات التي تستخدم نوعًا واحدًا من المقابس تكون قادرة عمومًا على الشحن في أنواع أخرى من محطات الشحن من خلال استخدام محولات المقابس.[140]

موصل النوع 2 هو النوع الأكثر شيوعًا من المقابس، لكن تستخدم إصدارات مختلفة في الصين وأوروپا.[141][142]

الموصل Type 1 (يسمى أيضاً SAE J1772) هو الشائع في أمريكا الشمالية[143][144] ولكنه نادر في أي مكان آخر، لأنه لا يدعم الشحن ثلاثي الطور.[145]

الشحن اللاسلكي، إما للسيارات الثابتة أو كطريق كهربائي،[146] أصبح أقل شيوعاً اعتباراً من 2021، لكنه يستخدم في بعض المدن لسيارات الأجرة.[147][148]

الشحن المنزلي

عادةً ما يتم شحن السيارات الكهربائية طوال الليل من محطة الشحن المنزلية؛ التي تُعرف أحيانًا باسم نقطة الشحن، أو شاحن صندوق الحائط، أو ببساطة الشاحن؛ في المرآب أو خارج المنزل.[149][150] اعتباراً من 2021، كانت الشواحن المنزلية التقليدية بقدرة 7 ك.و، لكن لا تتضمن جميعها الشحن الذكي.[149] بالمقارنة مع مركبات الوقود الأحفوري، تتضاءل الحاجة إلى الشحن باستخدام البنية التحتية العامة بسبب فرص الشحن المنزلي؛ يمكن توصيل المركبات وبدء كل يوم بشحن كامل للمركبة.[151] من الممكن أيضًا الشحن من منفذ قياسي لكنه بطيء جدًا.

محطات الشحن العامة

تكون محطات الشحن العامة دائمًا أسرع من الشواحن الشحن المنزلية،[152] مع العديد من توفير التيار المستمر لتجنب عنق الزجاجة الناتج عن المرور عبر محول التيار المتردد إلى التيار المستمر في السيارة،[153] اعتباراً من عام 2021، كانت قدرة أسرع شاحن 35 ك.و.[154]

نظام الشحن المجمع (CCS) هو معيار الشحن الأكثر انتشارًا،[142] بينما يُستخدم معيار GB/T 27930 في الصين، وCHAdeMO في اليابان. ليس لدى الولايات المتحدة معيار فعلي، مع مزيج من محطات الشحن المجمع وشاحن تسلا الفائق ومحطات الشحن بمعيار CHAdeMO.

يستغرق شحن السيارة الكهربائية باستخدام محطات الشحن العامة وقتًا أطول من إعادة تزويد مركبة تعمل بالوقود الأحفوري بالوقود. تعتمد السرعة التي يمكن بها إعادة شحن السيارة على سرعة الشحن في محطة الشحن وقدرة السيارة على تلقي الشحن. اعتباراً من عام 2021، كانت هناك سيارات 400 ڤولت وأخرى 800 ڤولت.[155] إن توصيل مركبة يمكنها استيعاب الشحن الفائق بمحطة شحن ذات معدل شحن مرتفع للغاية يمكن أن يعيد ملء بطارية السيارة إلى 80% خلال 15 دقيقة.[156]

قد تستغرق المركبات ومحطات الشحن ذات سرعات الشحن الأبطأ ما يصل إلى ساعتين لإعادة ملء البطارية إلى 80%. وكما هو الحال مع الهاتف المحمول، فإن نسبة 20% الأخيرة تستغرق وقتًا أطول لأن الأنظمة تبطئ لملء البطارية بأمان وتجنب إتلافها.

تقوم بعض الشركات ببناء محطات تبديل البطاريات لتقليل الوقت الفعلي لإعادة الشحن بشكل كبير.[157][158]

تحتوي بعض السيارات الكهربائية (على سبيل المثال، بي إم دبليو آي3) على موسع نطاق اختياري يعمل بالگازولين. صُمم هذا النظام ليكون بمثابة نظام احتياطي للطوارئ لتوسيع النطاق إلى موقع إعادة الشحن التالي، وليس للسفر لمسافات طويلة.[159]

الطرق الكهربائية

اعتبارًا من عام 2013، جرى تقييم تقنيات الطرق الكهربائية التي تعمل على تشغيل وشحن المركبات الكهربائية أثناء القيادة في السويد.[160] وكان من المقرر الانتهاء من التقييم عام 2022.[161]

في أواخر عام 2022 أُعتمد المعيار الأول للمعدات الكهربائية على متن مركبة تعمل بنظام طرق القضبان المكهربة (ERS)، المعيار التقني 50717 CENELEC.[162] من المقرر نشر المعايير التالية، التي تشمل "قابلية التشغيل البيني الكامل" و"الحل الموحد والقابل للتشغيل البيني" لإمدادات الطاقة على مستوى الأرض، بحلول نهاية عام 2024، مع تقديم تفاصيل "المواصفات الكاملة للاتصالات وإمدادات الطاقة من خلال قضبان موصلة مدمجة في الطريق".[163][164] ومن المقرر أن يكتمل أول طريق كهربائي دائم في السويد بحلول عام 2026[165] على جزء من الطريق إي 20 بين هالسبرگ وأوربرو، يليه توسيع 3000 كيلومتر أخرى من الطرق الكهربائية بحلول عام 2045.[166] تعتبر المجموعة العمل التابعة لوزارة البيئة الفرنسية أن تقنيات إمدادات الطاقة على مستوى الأرض هي المرشح الأكثر ترجيحًا للطرق الكهربائية،[167] وأوصت باعتماد معيار الطرق الكهربائية الأوروپي الذي تمت صياغته مع السويد وألمانيا وإيطاليا وهولندا وإسپانيا وپولندا وغيرها.[168] تخطط فرنسا لاستثمار ما بين 30 إلى 40 بليون يورو بحلول عام 2035 في نظام طرق كهربائي يمتد 8800 كيلومتر لإعادة شحن السيارات والحافلات والشاحنات الكهربائية أثناء القيادة. وكان من المتوقع الإعلان عن مناقصتين لتقييم تقنيات الطرق الكهربائية بحلول عام 2023.[167]

المركبة-إلى-الشبكة: التحميل والتخزين المؤقت للشبكة

خلال فترات حمولة الذروة، عندما تكون تكلفة التوليد مرتفعة للغاية، يمكن للمركبات الكهربائية ذات قدرات الاتصال بالشبكة أن تساهم بالطاقة في الشبكة. ويمكن بعد ذلك إعادة شحن هذه المركبات خلال ساعات خارج أوقات الذروة بأسعار أرخص مع المساعدة في استيعاب توليد وقت الليل الزائد. تعمل البطاريات الموجودة في المركبات كنظام موزع لتخزين الطاقة.[169]

عمر البطارية

كما هو الحال مع جميع بطاريات الليثيوم-أيون، قد تتحلل بطاريات المركبات الكهربائية على مدى فترات طويلة من الزمن، خاصة إذا تم شحنها بشكل متكرر بنسبة 100%؛ ومع ذلك، قد يستغرق هذا عدة سنوات على الأقل قبل أن يصبح ملحوظًا.[170] الضمان النموذجي للبطارية لمدة 8 سنوات أو 160.000 كم،[171] لكنها عادةً ما تدوم لفترة أطول، ربما من 15 إلى 20 سنة في السيارة ثم المزيد من السنوات في استخدام آخر.[172]

السيارات الكهربائية المتوافرة حالياً

مبيعات السيارات الكهربائية

في ديسمبر 2019 أصبحت تسلا الشركة الرائدة عالميًا في تصنيع السيارات الكهربائية.[173][174] سيارتها مودل إس كانت السيارة الكهربائية القابلة للشحن الأكثر مبيعاً في العالم عامي 2015 و2016[175][176]، كان المودل 3 هي السيارة الكهربائية الأكثر مبيعًا في العالم لأربع سنوات متتالية، من 2018 حتى 2021، وكان المودل واي هي السيارة الكهربائية الأكثر مبيعًا عام 2022.[177][178][179][180][181] أوائل عام 2020 تجاوزت تسلا مودل 3 السيارة تسلا ليف لتصبح السيارة الكهربائية الأكثر مبيعاً تراكمياً في العالم.[19] في مارس 2020 أنتجت تسلا سيارتها الكهربائية رقم مليون، لتصبح أول شركة مصنعة للسيارات تفعل ذلك،[182] وفي يونيو 2021، أصبح المودل 3 أول سيارة كهربائية يباع منها أكثر من 1 مليون سيارة.[20] أُدرجت تسلا باعتبارها مُصنع السيارات الكهربائية الأكثر مبيعًا في العالم، سواء باعتبارها علامة تجارية أو من قبل مجموعة السيارات لمدة أربع سنوات متتالية، من 2018 حتى 2021.[178][183][184][185][179] في نهاية 2021، كانت المبيعات التراكمية العالمية لشركة تسلا منذ 2012، قد بلغت 2.3 مليون وحدة،[186] 936.222 منها عام 2021.[187]

بي واي دي أوتو هي شركة رائدة أخرى في تصنيع السيارات الكهربائية، حيث تأتي غالبية مبيعاتها من الصين. من عام 2018 حتى 2023، أنتجت بي واي دي ما يقرب من 3.18 مليون سيارة كهربائية بالكامل، وأُنتج 1.574.822 منها عام 2023 وحده.[188] في الربع الأخير من عام 2023، تجاوزت بي واي دي شركة تسلا باعتبارها مُصنع السيارات الكهربائية الأكثر مبيعًا من خلال بيع 526.409 سيارة كهربائية تعمل بالبطارية، بينما أنتجت تسلا 484.507 سيارة.[189][190]

اعتباراً من ديسمبر 2021، أُدرج تحالف رينو-نيسان-ميتسوبيشي كأحد الشركات الكبرى المصنعة للمركبات الكهربائية بالكامل، حيث يبلغ إجمالي مبيعات المركبات الكهربائية العالمية أكثر من مليون مركبة كهربائية خفيفة.، بما في ذلك تلك المصنعة بواسطة ميتسوبيشي موتورز منذ عام 2009.[191][192] تقود نيسان المبيعات العالمية ضمن التحالف، حيث بيع مليون سيارة وشاحنة صغيرة بحلول يوليو 2023،[193] تليها مجموعة رينو بأكثر من 397.000 سيارة كهربائية مباعة في جميع أنحاء العالم حتى ديسمبر 2020، بما في ذلك الدراجة الرباعية الثقيلة تويزي.[194] اعتباراً من يوليو 2023، بلغ إجمالي المبيعات العالمية أكثر من 650.000 وحدة منذ بداية الإنتاج.[193]

الشركات الرائدة الأخرى المصنعة للسيارات الكهربائية هي جي إي سي أيون (جزء من مجموعة جي إي سي، بمبيعات تراكمية بلغت 962.385 مبيعات تراكمية اعتباراص من ديسمبر 2023)،[195] سايك موتور بمبيعات بلغت 1.838.000 وحدة (يوليو 2023)، جيلي، وفولكسڤاگن.[196][197][198][199][200]

يسرد الجدول التالي السيارات الكهربائية بالكامل الأكثر مبيعًا على الإطلاق والقادرة على السير على الطرق السريعة بمبيعات عالمية تراكمية تزيد عن 250.000 وحدة:

| الشركة | المودل | صورة | إطلاقها في السوق | المبيعات العالمية | إجمالي المبيعات | المبيعات العالمية السنوية | الحالة | ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

تسلا |

تسلا مودل واي |  |

2020-03 | ~2.49 مليون | 2023-12 | 1.211.601 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [177][178][201][202][203][204] |

تسلا |

تسلا مودل 3 |  |

2017-07 | ~2.06 مليون | 2023-12 | 529.287 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [177][178][205][201][204] |

SAIC-GM-Wuling |

Wuling Hongguang Mini EV |  |

2020-07 | 1.218.640 | 2023-12 | 118.834 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [177][178][201][206][207] |

نيسان |

نيسان ليف |  |

2010-12 | ~650.000 | 2023-07 | 64.201 (2021) | في الإنتاج | [178][193] |

بي واي دي |

بي واي دي يوان پلس/ أتو 3 |

|

2022-02 | 614.260 | 2023-12 | 412.202 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [207][208] |

بي واي دي |

بي واي دي دولفين |

|

2021-08 | 602.434 | 2023-12 | 367.419 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [177][201][209][210] |

جي إيه سي |

أيو إس |

|

2019-05 | 485.369 | 2023-12 | 222.227 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [177][178][201][211][212][208] |

بي واي دي |

بيو واي دي تشين |

|

2016-03 | 454.157 | 2023-12 | 154.774 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [208][207][213][214][215] |

رينو |

رينو زوي |  |

2012-12 | 413.975 | 2023-06 | 15.706 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [194][216][217][218] |

فولكسڤاگن |

فولكسڤاگن آي دي.4 |

|

2020-09 | 493.219 | 2023-12 | 192.686 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [177][178][219][204] |

جي إي سي |

أيون واي |

|

2021-04 | 383.350 | 2023-12 | 229.555 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [208][207][213] |

بي واي دي |

بي واي دي هان |

|

2020-03 | 367.129 | 2023-12 | 106.502 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [208][207][213][214] |

تسلا |

تسلا مودل إس |  |

2012-06 | ~363.900 | 2022-12 | ~35,000 (2022) | في الإنتاج | [220] |

شيري |

Chery eQ1 |

|

2017-03 | 338.051 | 2023-12 | 29.744 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [221][222][223] |

هيونداي |

هيونداي كونا إلكتريك |

|

2018-05 | 329.643 | 2023-12 | 70.871 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [224] |

فولكسڤاگن |

فولكسڤاگن آي دي.3 |

|

2019-11 | 325.770 | 2023-12 | 139.268 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [225][226][227][204] |

هيونداي |

هيونداي أيونيك 5 |

|

2021-03 | 280.430 | 2023-12 | 114.988 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [224] |

بي واي دي |

بي واي دي سيگل |

|

2023-04 | 280.217 | 2023-12 | 280.217 (2023) | في الإنتاج | [210] |

| ملاحظات: (1) تشير إلى المركبات قادرة على السير على الطرق السريعة إذا كانت قادرة على تحقيق سرعة قصوى تبلغ 100 كم/ساعة على الأقل. | ||||||||

السيارات الكهربائية حسب البلد

عام 2021، وصل إجمالي عدد السيارات الكهربائية على طرقات العالم لنحو 16.5 مليون سيارة. ارتفعت مبيعات السيارات الكهربائية في الربع الأول من عام 2022 إلى 2 مليون سيارة.[228] تمتلك الصين أكبر أسطول من السيارات الكهربائية بالكامل قيد الاستخدام، مع 2.58 مليون سيارة نهاية عام 2019، أي أكثر من نصف (53.9%) مخزون السيارات الكهربائية في العالم.

منذ عام 2012، تجاوزت مبيعات السيارات الكهربائية بالكامل السيارات الهجينة.[229][180][181]

السياسات والحوافز الحكومية

طرحت العديد من الحكومات الوطنية والإقليمية والمحلية حول العالم سياسات لدعم تبني المركبات الكهربائية القابلة للتوصيل في الأسواق على نطاق واسع. وقد وُضعت مجموعة متنوعة من السياسات لتوفير: الدعم المالي للمستهلكين والمصنعين؛ الحوافز غير النقدية؛ الإعانات لنشر البنية التحتية للشحن؛ محطات شحن المركبات الكهربائية في المباني؛ واللوائح طويلة الأجل ذات أهداف محددة.[230][240][241]

| البلدان المختارة | السنة |

|---|---|

| النرويج(100% مبيعات م.ب.ع.) | 2025 |

| الدنمارك | 2030 |

| آيسلندا | |

| أيرلندا | |

| هولندا (100% مبيعات م.ب.ع.) | |

| السويد | |

| المملكة المتحدة (100% م.ب.ع.) | 2035 |

| فرنسا | 2040 |

| كندا (100% م.ب.ع.) | |

| سنغافورة | |

| ألمانيا (100% م.ب.ع.) | 2050 |

| الولايات المتحدة (10 ولايات م.ب.ع.) | |

| اليابان(100% مبيعات م.ك.هـ./م.ك.ق.ت./م.ب.ع.) |

تهدف الحوافز المالية للمستهلكين إلى جعل سعر شراء السيارة الكهربائية تنافسيًا مع السيارات التقليدية بسبب ارتفاع التكلفة الأولية للسيارات الكهربائية. اعتمادًا على حجم البطارية، هناك حوافز شراء لمرة واحدة مثل المنح والإعفاءات الضريبية؛ الإعفاءات من رسوم الاستيراد؛ الإعفاءات من رسوم الطرق ورسوم الازدحام؛ والإعفاء من رسوم التسجيل والرسوم السنوية.

من بين الحوافز غير النقدية، هناك العديد من الامتيازات مثل السماح للمركبات الكهربائية بالوصول إلى مسارات الحافلات ومسار المركبات عالي الإشغال، ومواقف السيارات المجانية والشحن المجاني.[240] بعض البلدان أو المدن التي تقيد ملكية السيارات الخاصة (على سبيل المثال، نظام حصص الشراء للمركبات الجديدة)، أو التي طبقت قيود القيادة الدائمة (على سبيل المثال، أيام عدم القيادة)، تستثني هذه المخططات السيارات الكهربائية لتشجيع اعتمادها.[243][244][245][246][247][248]

تقوم العديد من البلدان، بما في ذلك إنگلترة والهند، بإدخال لوائح تتطلب وجود محطات لشحن المركبات الكهربائية في بعض المباني.[241][249][250]

أنشأت بعض الحكومات أيضًا إشارات تنظيمية طويلة المدى بأهداف محددة مثل تفويضات المركبات بلا عادم (م.ب.ع.)، ولوائح انبعاثات ثاني أكسيد الكربون على المستوى الوطني أو الإقليمي، المعايير الاقتصادية الصارمة لاستهلاك الوقود، والتخلص التدريجي من مبيعات مركبات محرك الاحتراق الداخلي.[230][240] على سبيل المثال، حددت النرويج هدفًا وطنيًا هو أنه بحلول عام 2025 يجب أن تكون جميع مبيعات السيارات الجديدة عبارة عن مركبات بلا عادم (بالبطارية الكهربائية أو بالهيدروجين).[251][252] في حين أن هذه الحوافز تهدف إلى تسهيل التحول بشكل أسرع من سيارات الاحتراق الداخلي، إلا أنها تعرضت لانتقادات من قبل بعض الاقتصاديين لأنها خلقت فائض حمولة زائدة في سوق السيارات الكهربائية، مما قد يبطل جزئيًا المكاسب البيئية.[253][254][255]

خطط كبار مصنعي المركبات الكهربائية

لقد اكتسبت المركبات الكهربائية قوة جذب كبيرة باعتبارها جزءًا لا يتجزأ من مشهد السيارات العالمي في السنوات الأخيرة. اعتمدت شركات صناعة السيارات الكبرى من جميع أنحاء العالم المركبات الكهربائية كعنصر حاسم في خططها الاستراتيجية، مما يشير إلى تحول نموذجي نحو النقل المستدام.

| التاريخ | المصنع | الاستثمار | الإطار الزمني للاستثمار |

# م.ك. | السنة الهدف |

ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-11 | فولكسڤاگن | 86 بليون دولار | 2025 | 27 | 2022 | تخطط لإنتاج 27 مركبة كهربائية بحلول عام 2022، على منصة مخصصة للمركبات الكهربائية يطلق عليها اسم "مجموعة الأدوات الكهربائية المعيارية" والتي تم التوقيع عليها بالأحرف الأولى باسم MEB.[256] وفي نوفمبر 2020، أعلنت عن عزمها استثمار 86 بليون دولار في السنوات الخمس التالية، بهدف تطوير المركبات الكهربائية وزيادة حصتها في سوق المركبات الكهربائية. وسيشمل إجمالي الإنفاق الرأسمالي "المصانع الرقمية" وبرمجيات السيارات والسيارات ذاتية القيادة.[257] |

| 2020-11 | جنرال موتورز | 27 بليون دولار | 30 | 2035

[258] أعلنت أنها ستعزز استثماراتها في المركبات الكهربائية والمركبات القيادة الذاتية من 20 إلى 27 بليون دولار، وتخطط حاليًا لطرح 30 مركبة كهربائية في السوق بحلول نهاية عام 2025 (بما في ذلك: همر؛ وسيارة كاديلاك ليريك، وبويك، وجي إم سي، وشيڤروليه).[259] وصرحت المديرة التنفيذية للشركة ماري بارا إن 40% من السيارات التي ستقدمها جنرال موتورز في الولايات المتحدة ستكون عبارة عن مركبات كهربائية بالبطارية بحلول نهاية عام 2025.[260] تم تصميم منصة المركبات الكهربائية من الجيل التالي "BEV3" من جنرال موتورز لتكون مرنة للاستخدام في العديد من أنواع المركبات المختلفة، مثل تكوينات الدفع الأمامي والخلفي والدفع الرباعي.[261] | ||

| 2019-01 | مرسيدس | 23 بليون دولار | 2030 | 10 | 2022 | تخطط لزيادة تصنيع السيارات الكهربائية إلى 50% من المبيعات العالمية بحلول عام 2030.[262] |

| 2019-07 | فورد | 29 بليون دولار | 2025 | ستستخدم مجموعة أدوات فولكسڤاگن المعيارية ("MEB") لتصميم وبناء مركباتها الكهربائية بالكامل بدءًا من عام 2023.[264] فورد موستانگ ماك-إي هي سيارة كروس أوڤر كهربائية يمكنها قطع 480 كيلومترًا.[265] تخطط فورد لإطلاق السيارة الكهربائية إف-150 في الإطار الزمني لعام 2021.[266][267] | ||

| 2019-03 | بي إم دبليو | 12 | 2025 | تخطط لإنتاج 12 مركبة كهربائية بالكامل بحلول عام 2025، باستخدام بنية توليد القوة الكهربائية من الجيل الخامس، مما سيوفر الوزن والتكلفة ويزيد القدرة.[268] طلبت بي إم دبليو خلايا بطارية بقيمة 10 بليون يورو للفترة من 2021 حتى 2030.[269][270][271] | ||

| 2020-01 | هيونداي | 23 | 2025 | أعلنت أنها تخطط لإنتاج 23 سيارة كهربائية بالكامل بحلول عام 2025.[272] ستعلن هيونداي عن الجيل القادم من منصة المركبات الكهربائية، المسماة e-GMP، عام 2021.[273] | ||

| 2019-06 | تويوتا | قامت بتطوير منصة عالمية للمركبات الكهربائية تحمل اسم e-TNGA يمكنها استيعاب سيارات مركبات الرباعي ذات الثلاثة صفوف أو سيارات سيدان رياضية أو سيارات كروس أوفڤ صغيرة أو سيارات صغيرة تشبه الصندوق.[274] ستطلق تويوتا وسوبارو مركبة كهربائية جديدة على منصة مشتركة؛[275] سيكون بحجم سيارة تويوتا RAV4 أو سوبارو فورستر. | ||||

| 2019-04 | 29 من مصنعي السيارات | 300 بليون دولار | 2029 | خلص تحليل أجرته رويترز تضمن 29 من شركات تصنيع السيارات العالمية إلى أن مصنعي السيارات تخطط لإنفاق 300 بليون دولار على مدى السنوات الخمس إلى العشر القادمة على السيارات الكهربائية، ومن المتوقع أن يتم 45% من هذا الاستثمار في الصين.[276] | ||

| 2020-10 | فيات | أطلقت نسختها الكهربائية الجديدة من نيو 500 للبيع في أوروپا ابتداءً من أوائل عام 2021.[277][278] | ||||

| 2020-11 | نيسان | أعلنت عزمها بيع السيارات الكهربائية والهجينة فقط في الصين اعتبارًا من عام 2025، وطرح تسعة موديلات جديدة. وتشمل خطط نيسان الأخرى تصنيع نصف مركبات خالية من الانبعاثات ونصفها نصف مركبات هجينة تعمل بالبنزين والكهرباء، بحلول عام 2035.[279] عام 2018، أعلنت إنفينيتي، العلامة التجارية الفاخرة لنيسان، أنه بحلول عام 2021، ستكون جميع السيارات المطروحة حديثًا كهربائية أو هجينة.[280] | ||||

| 2020-12 | أودي | 35 بليون يورو | 2021–2025 | 20 | 2025 | 30 مودل كهربائي جديد بحلول عام 2025، منها 20 مركبة كهربائية قابلة للتوصيل.[281] بحلول عام 2030-2035، تعتزم أودي طرح المركبات الكهربائية فقط.[282] |

توقعات

بحسب دلويت، من المتوقع أن يصل إجمالي المبيعات العالمية للمركبات الكهربائية عام 2030 إلى 31.1 مليون وحدة.[283] وتوقعت وكالة الطاقة الدولية أن يصل إجمالي المخزون العالمي من المركبات الكهربائية إلى ما يقرب من 145 مليونًا بحلول عام 2030 في ظل السياسات الحالية، أو 230 مليونًا إذا أُعتمدت سياسات التنمية المستدامة.[284]

أرقام قياسية

أتمّ هولندي في سيدني أطول رحلة في العالم بسيارة كهربائية قطع خلالها 95 ألف كيلومتر بهدف الترويج لوسيلة النقل هذه المراعية للبيئة.وقد قاد فيبه ووكر سيارته "بلو باندت" التي حولّها إلى مركبة عاملة بالطاقة الكهربائية في 33 بلدا، في أطول رحلة في العالم بسيارة كهربائية، على ما أفاد صاحب هذه المبادرة.وقد احتاج لأكثر من ثلاث سنوات لإتمام هذه الرحلة الممتدة من هولندا إلى أستراليا. وموّل هذا المشروع من هبات ساهمت في تغذية "بلو باندت" بالكهرباء، فضلا عن تأمين المسكن والمأكل لصاحبها.وعبر ووكر بالهند وبورما وماليزيا وإندونيسيا وتركيا، متبعا في مساره الاقتراحات التي كان يتلقاها على موقعه الإلكتروني.

وقال: "أسعى إلى تغيير العقليات وإلهام الناس لاعتماد مركبات كهربائية من خلال استعراض منافعها المستدامة".وأشار إلى أنه لم ينفق سوى 300 دولار لتغذية سيارته بالكهرباء خلال الرحلة بكاملها. وقال ووكر لمشجعين كانوا في استقباله عندما وصل إلى خط النهاية "ساعدني نحو 1800 شخص في رحلتي عبر أوروبا والشرق الأوسط والهند وجنوب شرق آسيا وأخيرا وصلت اليوم إلى هنا".

وبعد الساعة الثانية ظهرا بالتوقيت المحلي بقليل عبر ووكر وموكب من السيارات الكهربائية جسر هاربور الشهير في سيدني قبل أن ينهي رحلته الطويلة في حديقة النباتات الملكية بجوار دار أوبرا سيدني. [285]

انظر أيضاً

- مركبة كهربائية

- سيارة شمسية

- كفاءة طاقة السيارة الكهربائية

- الدراجات البخارية والسكوتر الكهربائي

- أصوات تحذير المركبة الكهربائية - أصوات المركبات لسلامة المشاة

- رياضة المحركات الآلية الكهربائية

- Eco Grand Prix

- رياضة المحركات الآلية

- قائمة السيارات الكهربائية المتوافرة حالياً

- مركبة لكل شيء (V2X)

- التخلص التدريجي من مركبات الوقود الأحفوري

المصادر

- ^ "Reducing Pollution with Electric Vehicles". www.energy.gov (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ^ "How to charge an electric car". Carbuyer (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ^ "Executive summary – Global EV Outlook 2023 – Analysis". IEA (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ "Governor Newsom Announces California Will Phase Out Gasoline-Powered Cars & Drastically Reduce Demand for Fossil Fuel in California's Fight Against Climate Change". California Governor (in الإنجليزية). 2020-09-23. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Groom, David Shepardson, Nichola (2020-09-29). "U.S. EPA chief challenges California effort to mandate zero emission vehicles in 2035". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-09-29.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thunberg, Greta; Anable, Jillian; Brand, Christian (2022). "Is the Future Electric?". The Climate Book. Penguin. pp. 271–275. ISBN 978-0593492307.

- ^ "EU proposes effective ban for new fossil-fuel cars from 2035". Reuters. 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- ^ "IEA: EVs Will Account For 20% Of All Car Sales This Year". OilPrice.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ "How China put nearly 5 million new energy vehicles on the road in one decade | International Council on Clean Transportation". theicct.org. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-10-30.

- ^ Liu Wanxiang (2017-01-12). "中汽协:2016年新能源汽车产销量均超50万辆,同比增速约50%" [China Auto Association: 2016 new energy vehicle production and sales were over 500,000, an increase of about 50%] (in Chinese). D1EV.com. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) Chinese sales of new energy vehicles in 2016 totaled 507,000, consisting of 409,000 all-electric vehicles and 98,000 plug-in hybrid vehicles. - ^ Automotive News China (2018-01-16). "Electrified vehicle sales surge 53% in 2017". Automotive News China. Retrieved 2020-05-22. Chinese sales of domestically-built new energy vehicles in 2017 totaled 777,000, consisting of 652,000 all-electric vehicles and 125,000 plug-in hybrid vehicles. Sales of domestically-produced new energy passenger vehicles totaled 579,000 units, consisting of 468,000 all-electric cars and 111,000 plug-in hybrids. Only domestically built all-electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids and fuel cell vehicles qualify for government subsidies in China.

- ^ "中汽协:2018年新能源汽车产销均超125万辆,同比增长60%" [China Automobile Association: In 2018, the production and sales of new energy vehicles exceeded 1.25 million units, a year-on-year increase of 60%] (in Chinese). D1EV.com. 2019-01-14. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) Chinese sales of new energy vehicles in 2018 totaled 1.256 million, consisting of 984,000 all-electric vehicles and 271,000 plug-in hybrid vehicles. - ^ Kane, Mark (2020-02-04). "Chinese NEVs Market Slightly Declined In 2019: Full Report". InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 2020-05-30. Sales of new energy vehicles totaled 1,206,000 units in 2019, down 4.0% from 2018, and includes 2,737 fuel cell vehicles. Battery electric vehicle sales totaled 972,000 units (down 1.2%) and plug-in hybrid sales totaled 232,000 vehicles (down 14.5%). Sales figures include passenger cars, buses and commercial vehicles..

- ^ China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) (2021-01-14). "Sales of New Energy Vehicles in December 2020". CAAM. Retrieved 2021-02-08. NEV sales in China totaled 1.637 million in 2020, consisting of 1.246 million passenger cars and 121,000 commercial vehicles.

- ^ China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) (2022-01-12). "Sales of New Energy Vehicles in December 2021". CAAM. Retrieved 2022-01-13. NEV sales in China totaled 3.521 million in 2021 (all classes), consisting of 3.334 million passenger cars and 186,000 commercial vehicles.

- ^ أ ب Preston, Benjamin (8 October 2020). "EVs Offer Big Savings Over Traditional Gas-Powered Cars". Consumer Reports (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ^ أ ب "Electric Cars: Calculating the Total Cost of Ownership for Consumers" (PDF). BEUC (The European Consumer Organisation). 25 April 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2021.

- ^ "The Tesla Model Y Is The Best-Selling Car In The World | GreenCars". www.greencars.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ أ ب ت Holland, Maximilian (2020-02-10). "Tesla Passes 1 Million EV Milestone & Model 3 Becomes All Time Best Seller". CleanTechnica. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ أ ب ت Shahan, Zachary (2021-08-26). "Tesla Model 3 Has Passed 1 Million Sales". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 2021-08-26.

- ^ Hamid, Umar Zakir Abdul (2022). "Autonomous, Connected, Electric and Shared Vehicles: Disrupting the Automotive and Mobility Sectors". US: SAE. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "US Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 49 CFR Part 571 Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards". Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ^ "Citizens' summary EU proposal for a Regulation on L-category vehicles (two- or three-wheel vehicles and quadricycles)". European Commission. 2010-10-04. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Roth, Hans (March 2011). Das erste vierrädrige Elektroauto der Welt [The first four-wheeled electric car in the world] (in الألمانية). pp. 2–3.

- ^ Wakefield, Ernest H (1994). History of the Electric Automobile. Society of Automotive Engineers. pp. 2–3. ISBN 1-5609-1299-5.

- ^ Guarnieri, M. (2012). "Looking back to electric cars".: 1–6. doi:10.1109/HISTELCON.2012.6487583.

- ^ "Electric Car History". Archived from the original on 2014-01-05. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ^ "World's first electric car built by Victorian inventor in 1884". The Daily Telegraph. London. 2009-04-24. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ^ Boyle, David (2018). 30-Second Great Inventions. Ivy Press. p. 62. ISBN 9781782406846.

- ^ Denton, Tom (2016). Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 9781317552512.

- ^ "Elektroauto in Coburg erfunden" [Electric car invented in Coburg]. Neue Presse Coburg (in الألمانية). Germany. 2011-01-12. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- ^ أ ب "The History of the Electric Car". Energy.gov (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-05.

- ^ "Electric automobile". Encyclopædia Britannica (online). Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ^ Gerdes, Justin (2012-05-11). "The Global Electric Vehicle Movement: Best Practices From 16 Cities". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ^ Says, Alan Brown (9 July 2012). "The Surprisingly Old Story of London's First Ever Electric Taxi". Science Museum Blog (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Handy, Galen (2014). "History of Electric Cars". The Edison Tech Center. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ^ "Some Facts about Electric Vehicles". Automobilesreview. 2012-02-25. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ Gertz, Marisa; Grenier, Melinda (2019-01-05). "171 Years Before Tesla: The Evolution of Electric Vehicles". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- ^ Cub Scout Car Show, January 2008, http://www.macscouter.com/CubScouts/PowWow07/SCCC_2007/CubScoutThemes/Jan_2008.pdf, retrieved on 2009-04-12

- ^ Laukkonen, J.D. (1 October 2013). "History of the Starter Motor". Crank Shift. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

This starter motor first showed up on the 1912 Cadillac, which also had the first complete electrical system, since the starter doubled as a generator once the engine was running. Other automakers were slow to adopt the new technology, but electric starter motors would be ubiquitous within the next decade.

- ^ http://www.np-coburg.de/lokal/coburg/coburg/Elektroauto-in-Coburg-erfunden;art83423,1491254 np-coburg.de

- ^ "Elwell-Parker, Limited". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ أ ب ت Sperling, Daniel; Gordon, Deborah (2009). Two billion cars: driving toward sustainability. Oxford University Press. pp. 22–26. ISBN 978-0-19-537664-7.

- ^ Boschert, Sherry (2006). Plug-in Hybrids: The Cars that will Recharge America. New Society Publishers. pp. 15–28. ISBN 978-0-86571-571-4.

- ^ See Who Killed the Electric Car? (2006)

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (2015-04-26). "Electric Car Evolution". Clean Technica. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-08. 2008: The Tesla Roadster becomes the first production electric vehicle to use lithium-ion battery cells as well as the first production electric vehicle to have a range of over 200 miles on a single charge.

- ^ Blum, Brian. Totaled : the billion-dollar crash of the startup that took on big auto, big oil and the world. ISBN 978-0-9830428-2-2. OCLC 990318853.

- ^ Kim, Chang-Ran (2010-03-30). "Mitsubishi Motors lowers price of electric i-MiEV". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ "Best-selling electric car". Guinness World Records. 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-02-16. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ David B. Sandalow, ed. (2009). Plug-In Electric Vehicles: What Role for Washington? (1st. ed.). The Brookings Institution. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-8157-0305-1. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2011.See Introduction

- ^ "DRIVING A GREEN FUTURE: A RETROSPECTIVE REVIEW OF CHINA'S ELECTRIC VEHICLE DEVELOPMENT AND OUTLOOK FOR THE FUTURE" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Automakers raise prices for NEVs in China ahead of subsidy cuts". KrASIA (in الإنجليزية). 2022-01-03. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ Evans, Scott (2019-07-10). "2013 Tesla Model S Beats Chevy, Toyota, and Cadillac for Ultimate Car of the Year Honors". MotorTrend. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

We are confident that, were we to summon all the judges and staff of the past 70 years, we would come to a rapid consensus: No vehicle we've awarded, be it Car of the Year, Import Car of the Year, SUV of the Year, or Truck of the Year, can equal the impact, performance, and engineering excellence that is our Ultimate Car of the Year winner, the 2013 Tesla Model S.

- ^ "Global EV Outlook 2023 / Trends in electric light-duty vehicles". International Energy Agency. April 2023. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023.

- ^ Data from McKerracher, Colin (12 January 2023). "Electric Vehicles Look Poised for Slower Sales Growth This Year". BloombergNEF. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023.

- ^ Ali, Shirin (23 March 2022). "More Americans are buying electric vehicles, as gas car sales fall, report says". The Hill.

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (23 March 2022). "Oman makes first electric car in the Middle East". Green Prophet. Canada. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (22 May 2022). "Turkey's all electric Togg EV". Green Prophet. Canada. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Eddie Spence (2020-10-04). "U.S. Takes Stake in Battery-Metals Firm to Wean Itself Off China". بلومبرگ.

- ^ "Trotz fallender Batteriekosten bleiben E-Mobile teuer" [Despite falling battery costs electric cars remain expensive]. Umwelt Dialog (in الألمانية). Germany. 2018-07-31. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- ^ Hauri, Stephan (2019-03-08). "Wir arbeiten mit Hochdruck an der Brennstoffzelle" [We are working hard on the fuel cell]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in الألمانية). Switzerland. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- ^ Ward, Jonathan (2017-04-28). "EV supply chains: Shifting currents". Automotive Logistics. Archived from the original on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ^ Ouyang, Danhua; Zhou, Shen; Ou, Xunmin (2021-02-01). "The total cost of electric vehicle ownership: A consumer-oriented study of China's post-subsidy era". Energy Policy (in الإنجليزية). 149: 112023. Bibcode:2021EnPol.14912023O. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112023. ISSN 0301-4215. S2CID 228862530.

- ^ "Four of the Five Least Expensive Car Brands to Maintain Are American". Consumer Reports (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2024-04-23. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "Large Auto Leasing Company: Electric Cars Have Mostly Lower Total Cost in Europe". CleanTechnica. 9 May 2020. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Birmingham clean air charge: What you need to know". BBC. 13 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – Japanese Government Incentives for the Purchase of Environmentally Friendly Vehicles" (PDF). Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-26. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ^ Motavalli, Jim (2010-06-02). "China to Start Pilot Program, Providing Subsidies for Electric Cars and Hybrids". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Growing Number of EU Countries Levying CO2 Taxes on Cars and Incentivizing Plug-ins". Green Car Congress. 2010-04-21. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "Notice 2009–89: New Qualified Plug-in Electric Drive Motor Vehicle Credit". Internal Revenue Service. 2009-11-30. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ "Batteries For Electric Cars Speed Toward a Tipping Point". Bloomberg.com (in الإنجليزية). 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2021-03-04.

- ^ "EV-internal combustion price parity forecast for 2023 – report". MINING.COM (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ "Why are electric cars expensive? The cost of making and buying an EV explained". Hindustan Times (in الإنجليزية). 2020-10-23. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ Stock, Kyle (2018-01-03). "Why early EV adopters prefer leasing – by far". Automotive News. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ Ben (2019-12-14). "Should I Lease An Electric Car? What To Know Before You Do". Steer (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ "Subsidies slash EV lease costs in Germany, France". Automotive News Europe (in الإنجليزية). 2020-07-15. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ "To Save the Planet, Get More EVs Into Used Car Lots". Wired (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ Wayland, Michael (2022-06-22). "Raw material costs for electric vehicles have doubled during the pandemic". CNBC. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- ^ McMahon, Jeff. "Electric Vehicles Cost Less Than Half As Much To Drive". Forbes (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ "How much does it cost to charge an electric car?". Autocar (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-08-01.

- ^ Kaminski, Joe (17 August 2021). "The U.S. States Where You'll Save the Most Switching from Gas to Electric Vehicles". www.mroelectric.com. MRO Electric. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Romero, Simon (2009-02-02). "In Bolivia, Untapped Bounty Meets Nationalism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Página sobre el Salar (Spanish)". Evaporiticosbolivia.org. Archived from the original on 2011-03-23. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ^ "Vehicle exhaust emissions | What comes out of a car exhaust? | RAC Drive". www.rac.co.uk (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- ^ "Tyre pollution 1000 times worse than tailpipe emissions". www.fleetnews.co.uk (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ Baensch-Baltruschat, Beate; Kocher, Birgit; Stock, Friederike; Reifferscheid, Georg (2020-09-01). "Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP) - A review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment". Science of the Total Environment (in الإنجليزية). 733: 137823. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.733m7823B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137823. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 32422457.

- ^ "EVs: Clean Air and Dirty Brakes". The BRAKE Report (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2019-07-02. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ "Statement on the evidence for health effects associated with exposure to non-exhaust particulate matter from road transport" (PDF). UK Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2020.

- ^ "A global comparison of the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of combustion engine and electric passenger cars | International Council on Clean Transportation". theicct.org. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- ^ "Electric car switch on for health benefits". UK: Inderscience Publishers. 2019-05-16. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-01.

- ^ Greim, Peter; Solomon, A. A.; Breyer, Christian (2020-09-11). "Assessment of lithium criticality in the global energy transition and addressing policy gaps in transportation". Nature Communications (in الإنجليزية). 11 (1): 4570. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4570G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18402-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7486911. PMID 32917866.

- ^ Casson, Richard. "We don't just need electric cars, we need fewer cars". Greenpeace International. Greenpeace. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "Let's Count the Ways E-Scooters Could Save the City". Wired. December 7, 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Brand, Christian (29 March 2021). "Cycling is ten times more important than electric cars for reaching net-zero cities". The Conversation (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ Laughlin, Jason (January 29, 2018). "Why is Philly Stuck in Traffic?". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (2022-04-20). The EIB Climate Survey 2021-2022 - Citizens call for green recovery (in الإنجليزية). European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5223-8.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 3: Shopping for a new car? Most Europeans say they will opt for hybrid or electric". EIB.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ fm (2022-02-02). "Cypriots prefer hybrid or electric cars". Financial Mirror (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ "Germans less enthusiastic about electric cars than other Europeans - survey". Clean Energy Wire (in الإنجليزية). 2022-02-01. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ Rahmani, Djamel; Loureiro, Maria L. (2018-03-21). "Why is the market for hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) moving slowly?". PLOS ONE (in الإنجليزية). 13 (3): e0193777. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1393777R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193777. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5862411. PMID 29561860.

- ^ "67% of Europeans will opt for a hybrid or electric vehicle as their next purchase, says EIB survey". Mayors of Europe (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2022-02-02. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ Threewitt, Cherise (15 January 2019). "Gas-powered vs. Electric Cars: Which Is Faster?". How Stuff Works. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "In-wheel motors: The benefits of independent wheel torque control". E-Mobility Technology (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- ^ Hedlund, R. (November 2008). "The Roger Hedlund 100 MPH Club". National Electric Drag Racing Association. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ^ DeBord, Matthew (2017-11-17). "The new Tesla Roadster can do 0–60 mph in less than 2 seconds – and that's just the base version". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ "All-Electric Vehicles". www.fueleconomy.gov (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ^ أ ب Shah, Saurin D. (2009). "2". Plug-In Electric Vehicles: What Role for Washington? (1st ed.). The Brookings Institution. pp. 29, 37 and 43. ISBN 978-0-8157-0305-1.

- ^ "Electric Car Myth Buster – Efficiency". CleanTechnica (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2018-03-10. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ^ Sensiba, Jennifer (2019-07-23). "EV Transmissions Are Coming, And It's A Good Thing". CleanTechnica. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ "Can heat pumps solve cold-weather range loss for EVs?". Green Car Reports (in الإنجليزية). 8 August 2019. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ NativeEnergy (2012-09-07). "3 Electric Car Myths That Will Leave You Out in the Cold". Recyclebank. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ^ Piotrowski, Ed (2013-01-03). "How i Survived the Cold Weather". The Daily Drive – Consumer Guide Automotive. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ^ "Effects of Winter on Tesla Battery Range and Regen". teslarati.com. 2014-11-24. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- ^ "2010 Options and Packages". Toyota Prius. Toyota. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- ^ "ISO 6469-1:2019 Electrically propelled road vehicles — Safety specifications — Part 1: Rechargeable energy storage system (RESS)". ISO. April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "ISO 6469-2:2018 Electrically propelled road vehicles — Safety specifications — Part 2: Vehicle operational safety". ISO. February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ "ISO 6469-3:2018 Electrically propelled road vehicles — Safety specifications — Part 3: Electrical safety". ISO. October 2018. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ National Research Council; Transportation Research Board; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Board on Energy and Environmental Systems; Committee on the Effectiveness and Impact of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards (2002). Effectiveness and Impact of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards. National Academies Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-309-07601-2. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "Vehicle Weight, Fatality Risk and Crash Compatibility of Model Year 1991–99 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks" (PDF). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. October 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ^ Valdes-Dapena, Peter (7 June 2021). "Why electric cars are so much heavier than regular cars". CNN Business. CNN. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ Wang, Peiling (2020). "Effect of electric battery mass distribution on electric vehicle movement safety". Vibroengineering PROCEDIA (in الإنجليزية). 33: 78–83. doi:10.21595/vp.2020.21569. S2CID 225065995. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "Protean Electric's In-Wheel Motors Could Make EVs More Efficient". IEEE Spectrum (in الإنجليزية). 2018-06-26. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ Spotnitz, R.; Franklin, J. (2003). "Abuse behavior of high-power, lithium-ion cells". Journal of Power Sources. 113 (1): 81–100. Bibcode:2003JPS...113...81S. doi:10.1016/S0378-7753(02)00488-3. ISSN 0378-7753.

- ^ "Roadshow: Electric cars not as likely to catch fire as gasoline powered vehicles". The Mercury News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2018-03-29. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ^ "Detroit First Responders Get Electric Vehicle Safety Training". General Motors News (Press release). 2011-01-19. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ "General Motors Kicks Off National Electric Vehicle Training Tour For First Responders". Green Car Congress. 2010-08-27. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ^ AOL Autos (2011-12-16). "Chevy Volt Unplugged: When To Depower Your EV After a Crash". Translogic. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ^ "2011 LEAF First Responder's Guide" (PDF). Nissan North America. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ^ "What firefighters need to know about electric car batteries". FireRescue1 (in الإنجليزية). 22 February 2017. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "04.8 EV fire reignition". EV Fire Safe (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-06-06.

- ^ "Ford Focus BEV – Road test". Autocar.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Lampton, Christopher (23 January 2009). "How Regenerative Braking Works". HowStuffWorks.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "What happens to old electric vehicle batteries?". WhichCar (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ "What Tesla's bet on iron-based batteries means for manufacturers". TechCrunch (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 28 July 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-11.[dead link]

- ^ قالب:Fuel Economy Guide

- ^ (2 May 2017) "Electric vehicles connection to microgrid effects on peak demand with and without demand response" in 2017 Iranian Conference.: 1272–1277, IEEE. doi:10.1109/IranianCEE.2017.7985237.

- ^ "Best small electric cars 2021". Auto Express (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-08-11.

- ^ Lambert, Fred (2016-09-06). "AAA says that its emergency electric vehicle charging trucks served "thousands" of EVs without power". Electrek. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- ^ "Diginow Super Charger V2 opens up Tesla destination chargers to other EVs". Autoblog (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ "ELECTRIC VEHICLE CHARGING IN CHINA AND THE UNITED STATES" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2019.

- ^ أ ب "CCS Combo Charging Standard Map: See Where CCS1 And CCS2 Are Used". InsideEVs (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "Rulemaking: 2001-06-26 Updated and Informative Digest ZEV Infrastructure and Standardization" (PDF). title 13, California Code of Regulations. California Air Resources Board. 2002-05-13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

Standardization of Charging Systems

- ^ "ARB Amends ZEV Rule: Standardizes Chargers & Addresses Automaker Mergers" (Press release). California Air Resources Board. 2001-06-28. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

the ARB approved the staff proposal to select the conductive charging system used by Ford, Honda and several other manufacturers

- ^ "ACEA position and recommendations for the standardization of the charging of electrically chargeable vehicles" (PDF). ACEA Brussels. 2010-06-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06.

- ^ "Magnetised concrete that charges electric vehicles on the move tested in America". Driving.co.uk from The Sunday Times (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2021-07-29. Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- ^ "Nottingham hosts wireless charging trial". www.fleetnews.co.uk (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- ^ Campbell, Peter (2020-09-09). "Electric vehicles to cut the cord with wireless charging". www.ft.com (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- ^ أ ب "How to charge your electric car at home". Autocar (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "The Best Home EV Charger Buying Guide For 2020". InsideEVs (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "Electric Vehicle Charging: Types, Time, Cost and Savings". Union of Concerned Scientists. 2018-03-09. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ "Thinking of buying an electric vehicle? Here's what you need to know about charging". USA Today (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ "DC Fast Charging Explained". EV Safe Charge (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "How electric vehicle (EV) charging works". Electrify America (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "New, 800V, electric cars, will recharge in half the time". The Economist. 2021-08-19. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- ^ "Electric Cars - everything you need to know". EFTM (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2019-04-02. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ "EV maker Nio to have 4,000 battery swapping stations globally in 2025". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "EV battery swapping startup Ample charges up operations in Japan, NYC". TechCrunch (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 16 June 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-01.[dead link]

- ^ Voelcker, John (12 March 2013). "BMW i3 Electric Car: ReX Range Extender Not For Daily Use?". Green Car Reports. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Swedish Transport Administration (November 29, 2017), National roadmap for electric road systems, https://www.trafikverket.se/contentassets/445611d179bf44938793269fe58376b6/dokument/national_roadmap_for_electric_road_systems_20171129_eng.pdf

- ^ Regler för statliga elvägar SOU 2021:73, Regeringskansliet (Government Offices of Sweden), September 1, 2021, pp. 291–297, https://www.regeringen.se/4a5530/contentassets/37e1f87a819e48ff9c79d615ff8fd8ec/sou-2021_73.pdf

- ^ PD CLC/TS 50717 Technical Requirements for Current Collectors for ground-level feeding system on road vehicles in operation, 2022, https://standardsdevelopment.bsigroup.com/projects/2020-03529, retrieved on January 2, 2023

- ^ Final draft: Standardization request to CEN-CENELEC on 'Alternative fuels infrastructure' (AFI II), European Commission, February 2, 2022, https://www.snv.ch/files/content/documents/News%20und%20Newslettertexte/CEN_CENELEC_BT-Dokument.pdf, retrieved on 2 January 2023

- ^ Matts Andersson (July 4, 2022), Regulating Electric Road Systems in Europe - How can a deployment of ERS be facilitated?, CollERS2 - Swedish German research collaboration on Electric Road Systems, https://electric-road-systems.eu/e-r-systems-wAssets/docs/publications/CollERS-2-Discussion-paper-2-Regulatory-issues.pdf

- ^ Electric Road Systems - PIARC Online Discussion, November 4, 2021, 14 minutes 25 seconds into the video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEdcdsLC88Y

- ^ Jonas Grönvik (September 1, 2021), Sverige på väg att bli först med elvägar – Rullar ut ganska snabbt, https://www.nyteknik.se/fordon/sverige-pa-vag-att-bli-forst-med-elvagar-rullar-ut-ganska-snabbt-7020044

- ^ أ ب Laurent Miguet (April 28, 2022), Sur les routes de la mobilité électrique, https://www.lemoniteur.fr/article/mobilite-electrique-2-5-une-fenetre-etroite-pour-brancher-les-autoroutes.2203237

- ^ Patrick Pélata (July 2021), Système de route électrique. Groupe de travail n°1, https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/GT1%20rapport%20final.pdf

- ^ "Groupe Renault begins large-scale vehicle-to-grid charging pilot". Renewable Energy Magazine. 22 March 2019. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Understanding the life of lithium ion batteries in electric vehicles". Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ "What happens to old electric car batteries? | National Grid Group". www.nationalgrid.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "Elektroauto: Elektronik-Geeks sind die Oldtimer-Schrauber von morgen" [Elektroauto: Electronics geeks are the classic car screwdrivers of tomorrow]. Zeit Online (in الألمانية). Germany. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Randall, Chris (2020-02-04). "Newest CAM study shows Tesla as EV sales leader". electricdrive.com. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Kane, Mark (2020-01-04). "Within Weeks, Tesla Model 3 Will Be World's Top-Selling EV of All Time". InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 2020-05-23.Cumulatively, Tesla has sold about 900,000 electric cars since 2008.

- ^ Cobb, Jeff (2017-01-26). "Tesla Model S Is World's Best-Selling Plug-in Car For Second Year in a Row". HybridCars.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-26. See also detailed 2016 sales and cumulative global sales in the two graphs.

- ^ Cobb, Jeff (2016-01-12). "Tesla Model S Was World's Best-Selling Plug-in Car in 2015". HybridCars.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Pontes, José (2023-02-07). "World EV Sales Report — Tesla Model Y Wins 1st Best Seller Title In Record Year". CleanTechnica (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2023-02-10. "The top 5 global best selling plug-in electric cars in 2022 were the Tesla Model Y (771,300), the BYD Song (BEV + PHEV) with 477,094, the Tesla Model 3 (476,336), the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV (424,031), and the BYD Qin Plus (BEV + PHEV) with 315,236. BYD Han (BEV + PHEV) sales totaled 273,323 units, BYD Yuan Plus 201,744 and VW ID.4 174,092 units."

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Jose, Pontes (2022-01-30). "World EV Sales — Tesla Model 3 Wins 4th Consecutive Best Seller Title In Record Year". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 2022-02-05. "The top 3 global best selling plug-in electric cars in 2021 were the Tesla Model 3 (500,713), the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV (424,138), and the Tesla Model Y (410,517). Nissan Leaf sales totaled 64,201 units and Chery eQ 68,821 units."

- ^ أ ب Jose, Pontes (2021-02-02). "Global Top 20 - December 2020". EVSales.com. Retrieved 2021-02-03. "Global sales totaled 3,124,793 plug-in passenger cars in 2020, with a BEV to PHEV ratio of 69:31, and a global market share of 4%. The world's top selling plug-in car was the Tesla Model 3 with 365,240 units delivered, and Tesla was the top selling manufacturer of plug-in passenger cars in 2019 with 499,535 units, followed by VW with 220,220."

- ^ أ ب ت Jose, Pontes (2020-01-31). "Global Top 20 - December 2019". EVSales.com. Retrieved 2020-05-10. "Global sales totaled 2,209,831 plug-in passenger cars in 2019, with a BEV to PHEV ratio of 74:26, and a global market share of 2.5%. The world's top selling plug-in car was the Tesla Model 3 with 300,075 units delivered, and Tesla was the top selling manufacturer of plug-in passenger cars in 2019 with 367,820 units, followed by BYD with 229,506."