تاريخ الفلپين

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ الفلپين |

| خط زمني |

| الآثار |

|

|

تاريخ الفلبين ضارب في القدم، إذ يرجع استيطان تلك الجزر إلى حوالـي 400,000 إلى 500,000 سنة مضت. وتُعد الهجرات من إندونيسيا وماليزيا منذ نحو سنة 3000ق.م إلى جزر الفلبين من أهم الهجرات إذ إن المؤرخين اليوم يعدون أولئك المهاجرين أسلاف سكان الفلبين الحاليين.

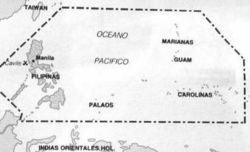

كان سكان جُزر الفلبين حتّى القرن السّادس عشر الميلادي يعيشون في مجموعات صغيرة موزّعة على نحو سبعة آلاف جزيرة، لا يربط بينها رابط، بل عاشت منفصلة بعضها عن بعض، تفصلها الأنهار والبحار والجبال، ولغاتها المتعّددة، وتقاليدها الثقافية والاجتماعية المختلفة. وظلوا على هذه الفُرقة حتّى مجيء الأسبان إلى الفلبين في القرن السادس عشر الميلادي حيث حاول هؤلاء توحيد هذه المجموعات المتباينة عن طريق فرض سلطة مركزيّة قوية، وعن طريق فرض النصرانية الكاثوليكية عليها. وكان من نتائج هذه المحاولة أن قسّم المؤرّخون تاريخ الفلبين إلى فترتين رئيسيّتين هما: الفترة الأسبانية، والفترة السابقة لها.

استمرّ الحكـم الأسبانيّ للفلبين لأكثر من ثلاثمـائة عـام، ـ من سنة 1565م إلى سنة 1898م ـ وانتهى باستقلال البلاد وإقامة أول جمهورية فيها، لكن هذه الجمهورية لم تستمر بسبب الصراع والحروب التي كانت دائرة بينها وبين الأسبان ثم الأمريكيين، والتي انتهت بشراء الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية جُزر الفلبين من الأسبان بمبلغ عشرين مليون دولار أمريكي. حيث بسطت تلك الدولة سيطرتها على الفلبين حتى الغزو الياباني لها في عام 1941م خلال الحرب العالمية الثانية. واستمرت السيطرة اليابانية حتى الرابع عشر من أكتوبر 1943م، وهو التاريخ الذي منحت فيه اليابان الفلبين استقلالها السياسي، وأقامت الجمهورية الفلبينية الثانية؛ لكن سرعان ما عادت الجيوش الأمريكية للفلبين، حيث حاربت اليابانيين وهزمتهم هناك، ثم مُنحت الفلبين استقلالها التام في الرابع من يوليو 1946م. تعاقب على حكم الفلبين بعد هذا التاريخ رؤساء وطنيون عديدون، آخرهم فرديناند ماركوس الذي أزاحت حكمه الفردي ثورة شعبية في عام 1986م، وخلفته كورازون أكينو أول امرأة رئيسة للفلبين، ثم فيدل راموس عام 1992م.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خط زمني

قبل التاريخ

Discovery in 2018 of stone tools and fossils of butchered animal remains in Rizal, Kalinga has pushed back evidence of early hominins in the country to as early as 709,000 years.[1] Some archeological evidence was found that humans lived in the archipelago 67,000 years ago, with the "Callao Man" of Cagayan and the Angono Petroglyphs in Rizal suggesting the presence of human settlement before the arrival of the Negritos and Austronesian speaking people.[2][3][4][5] Continued excavations in Callao Cave however led to 12 bones from three hominin individuals being identified as a new species named Homo luzonensis.[6] For modern humans, the Tabon remains are the still oldest known at about 47,000 years.[7]

The Negritos were early settlers,[8] but their appearance in the Philippines has not been reliably dated.[9] They were followed by speakers of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, a branch of the Austronesian language family. The first Austronesians reached the Philippines at 3000-2200 BC, settling the Batanes Islands and northern Luzon. From there, they rapidly spread downwards to the rest of the islands of the Philippines and Southeast Asia, as well as voyaging further east to reach the Northern Mariana Islands by around 1500 BC.[10][11][12][13] They assimilated the earlier Australo-Melanesian Negritos, resulting in the modern Filipino ethnic groups that all display various ratios of genetic admixture between Austronesian and Negrito groups.[14][15] Before the expansion out of Taiwan, archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence had linked Austronesian speakers in Insular Southeast Asia to cultures such as the Hemudu, its successor the Liangzhu[13][16] and Dapenkeng in Neolithic China.[17][18][19][20][21]

The most widely accepted theory of the population of the islands is the "Out-of-Taiwan" model that follows the Austronesian expansion during the Neolithic in a series of maritime migrations originating from Taiwan that spread to the islands of the Indo-Pacific; ultimately reaching as far as New Zealand, Easter Island, and Madagascar.[11][22] Austronesians themselves originated from the Neolithic rice-cultivating pre-Austronesian civilizations of the Yangtze River delta in coastal southeastern China pre-dating the conquest of those regions by the Han Chinese. This includes civilizations like the Liangzhu culture, Hemudu culture, and the Majiabang culture.[23] It connects speakers of the Austronesian languages in a common linguistic and genetic lineage, including the Taiwanese indigenous peoples, Islander Southeast Asians, Chams, Islander Melanesians, Micronesians, Polynesians, and the Malagasy people. Aside from language and genetics, they also share common cultural markers like multihull and outrigger boats, tattooing, rice cultivation, wetland agriculture, teeth blackening, jade carving, betel nut chewing, ancestor worship, and the same domesticated plants and animals (including dogs, pigs, chickens, yams, bananas, sugarcane, and coconuts).[11][22][24]

A 2021 genetic study, which examined representatives of 115 indigenous communities, found evidence of at least five independent waves of early human migration. Negrito groups, divided between those in Luzon and those in Mindanao, may come from a single wave and diverged subsequently, or through two separate waves. This likely occurred sometime after 46,000 years ago. Another Negrito migration entered Mindanao sometime after 25,000 years ago. Two early East Asian waves were detected, one most strongly evidenced among the Manobo people who live in inland Mindanao, and the other in the Sama-Bajau and related people of the Sulu archipelago, Zamboanga Peninsula, and Palawan. The admixture found in the Sama people indicates a relationship with the Lua and Mlabri people of mainland Southeast Asia, both peoples being speakers of an Austroasiatic language and reflects a similar genetic signal found in western Indonesia. These happened sometime after 15,000 years ago and 12,000 years ago respectively, around the time the last glacial period was coming to an end. Austronesians, either from Southern China or Taiwan, were found to have come in at least two distinct waves. The first, occurring perhaps between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago, brought the ancestors of indigenous groups that today live around the Cordillera Central mountain range. Later migrations brought other Austronesian groups, along with agriculture, and the languages of these recent Austronesian migrants effectively replaced those existing populations. In all cases, new immigrants appear to have mixed to some degree with existing populations. The integration of Southeast Asia into Indian Ocean trading networks around 2,000 years ago also shows some impact, with South Asian genetic signals present within some Sama-Bajau communities. There is also some Papuan migration to Southeast Mindanao as Papuan genetic signatures were detected in the Sangil and Blaan ethnic groups.[25]

By 1000 BC, the inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago had developed into four distinct kinds of peoples: tribal groups, such as the Aetas, Hanunoo, Ilongots and the Mangyan who depended on hunter-gathering and were concentrated in forests; warrior societies, such as the Isneg and Kalinga who practiced social ranking and ritualized warfare and roamed the plains; the petty plutocracy of the Ifugao Cordillera Highlanders, who occupied the mountain ranges of Luzon; and the harbor principalities of the estuarine civilizations that grew along rivers and seashores while participating in trans-island maritime trade.[26] It was also during the first millennium BC that early metallurgy was said to have reached the archipelagos of maritime Southeast Asia via trade with India[27][28]

Around 300–700 AD, the seafaring peoples of the islands traveling in balangays began to trade with the Indianized kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago and the nearby East Asian principalities, adopting influences from both Buddhism and Hinduism.[29]

الطريق البحري لليشب

The Maritime Jade Road was initially established by the animist indigenous peoples between the Philippines and Taiwan, and later expanded to cover Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and other countries.[30] Artifacts made from white and green nephrite have been discovered at a number of archeological excavations in the Philippines since the 1930s. The artifacts have been both tools like adzes[31] and chisels, and ornaments such as lingling-o earrings, bracelets and beads.[32] Tens of thousands were found in a single site in Batangas.[33][34] The jade is said to have originated nearby in Taiwan and is also found in many other areas in insular and mainland Southeast Asia. These artifacts are said to be evidence of long range communication between prehistoric Southeast Asian societies.[35] Throughout history, the Maritime Jade Road has been known as one of the most extensive sea-based trade networks of a single geological material in the prehistoric world, existing for 3,000 years from 2000 BCE to 1000 CE.[36][37][38][39] The operations of the Maritime Jade Road coincided with an era of near absolute peace which lasted for 1,500 years, from from 500 BCE to 1000 CE.[40] During this peaceful pre-colonial period, not a single burial site studied by scholars yielded any osteological proof for violent death. No instances of mass burials were recorded as well, signifying the peaceful situation of the islands. Burials with violent proof were only found from burials beginning in the 15th century, likely due to the newer cultures of expansionism imported from India and China. When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, they recorded some war-like groups, whose cultures have already been influenced by the imported Indian and Chinese expansionist cultures of the 15th century.[41]

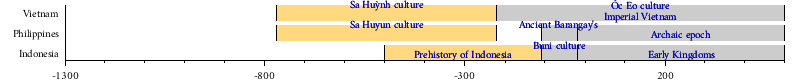

The Sa Huỳnh culture

The Sa Huỳnh culture centered on present-day Vietnam, showed evidence of an extensive trade network. Sa Huỳnh beads were made from glass, carnelian, agate, olivine, zircon, gold and garnet; most of these materials were not local to the region, and were most likely imported. Han dynasty-style bronze mirrors were also found in Sa Huỳnh sites.

Conversely, Sa Huỳnh produced ear ornaments have been found in archaeological sites in Central Thailand, Taiwan (Orchid Island), and in the Philippines, in the Palawan, Tabon Caves. One of the great examples is the Kalanay Cave in Masbate; the artefacts on the site in one of the "Sa Huỳnh-Kalanay" pottery complex sites were dated 400BC–1500 AD. The Maitum anthropomorphic pottery in the Sarangani Province of southern Mindanao is c. 200 AD.[42][43]

Ambiguity of what is Sa Huỳnh culture puts into question its extent of influence in Southeast Asia. Sa Huỳnh culture is characterized by use of cylindrical or egg-shaped burial jars associated with hat-shaped lids. Using its mortuary practice as a new definition, Sa Huỳnh culture should be geographically restricted across Central Vietnam between Hue City in the north and Nha Trang City in the south. Recent archeological research reveals that the potteries in Kalanay Cave are quite different from those of the Sa Huỳnh but strikingly similar to those in Hoa Diem site, Central Vietnam and Samui Island, Thailand. New estimate dates the artifacts in Kalanay cave to come much later than Sa Huỳnh culture at 200-300 AD. Bio-anthropological analysis of human fossils found also confirmed the colonization of Vietnam by Austronesian people from insular Southeast Asia in, e.g., the Hoa Diem site.[44][45]

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

فترة ماقبل الحكم الأسباني

سكن الفلبين قبل خمسين ألف عام أقوام جاءوها من جنوبي الصين، واستقروا قرب البحر والأنهار، وأقاموا حضارة خاصة بهم، لعل أهم مايميزها اعتقادهم في الأرواح وفي سيطرتها على أوجه حياتهم المختلفة، وكذلك اعتقادهم في الحياة بعد الموت، ومعرفتهم ضربًا من الكتابة.

عرفت الفلبين الإسلام أول ماعرفته عن طريق التجار الصينيين المسلمين. وعن طريق بعض الدعاة القادمين من سومطرة مثل الداعية راجا باگندا الذي جاء إلى منطقة سولو في عام 1390م داعيًا إلى الإسلام ووجد استجابة واسعة. وأعقبه داعية آخر ثم ثالث يُدعى أبو بكر من بالمباڠ، وتزوج ابنة راجا باگندا. ولما توفي راجا باغندا صار أبوبكر سلطانًا، وأسس سلطانه على النظام الإسلامي العربي. أما مينداناو فقد أدخل فيها الإسلام الداعية الإسلامي الشريف كابوڠسوان. وقبل مجيء الأسبان كان الإسلام قد انتشر في مانيلا وغيرها، وأصبحت مانيلا نفسها دارًا إسلامية، وكان سليمان، حاكم مانيلا، ذا نسب يربطه بسلطان بورنيو. لكن مجيء الأسبان إلى الفلبين حال دون انتشار الإسلام في الجُزُر الأخرى.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحقبة الأسبانية

السيطرة الأسبانية. كان البَحَّار البرتغالي فرديناند ماجلان أول من أقام صلة بين أسبانيا والفلبين، وذلك في عام 1521م، إذ وصل إلى جزيرة سَمَر أثناء رحلته الاستكشافية الشهيرة التي كان يحاول فيها إثبات أن الأرض كروية. فأقام علاقات مع حاكم تلك الجزيرة، وبدأ في نشر النصرانية بين سُكانها، ثم تلت حملة ماجلان حملات استكشافية أخرى أطلقت إحداها اسم الفلبين على تلك الجزر تخليدًا لملك أسبانيا فيليب الثاني، لكن الأسبان لم ينجحوا في إقامة قواعد لهم هناك إلاّ في عام 1562م حيث استطاعوا فرض هيمنتهم، وحولوا الفلبين إلى مستعمرة أسبانية، حيث نشروا النصرانية بين السكان ماعدا السكان المسلمين في إقليم مينداناو، وأدخلوا الحروف الرومانية، والمطبعة وبعض مظاهر حضارتهم الأسبانية الأوروبية، وأهم من ذلك استطاعوا إقامة حكومة مركزية قوية تمكنت من حكم البلاد بفاعلية، وأن تجعل من سكانها أمة واحدة، وقد تركزت المعارضة لحكمهم ولانتشار النصرانية، في أوساط السكان المسلمين في الجنوب الذين ظلوا شوكة في جنب الحكومة الأسبانية التي فشلت في إخضاعهم حتى نهاية حكمها في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر الميلادي.

نتج عن ازدهار التجارة إبان الحكم الأسباني ظهور طبقة وسطى من المستنيرين الذين تلقّوا تعليمهم في الجامعات الأوروبية، والذين كان لهم الفضل في المناداة بالإصلاح السياسي، ومن بعد ذلك في قيادة الثورات ضد الحكم الأسباني، والعمل على نيل الاستقلال. وقد نجحت إحدى تلك الثورات بمعاونة الأمريكيين في إنهاء الحكم الأسباني في أغسطس 1898م، وإعلان استقلال البلاد، لكن المطامع الأمريكية والرغبة في جعل الفلبين سوقًا جديدة للمنتجات الأمريكية أدت إلى اندلاع الحرب بين أهل الفلبين والجيوش الأمريكية، فكانت الغلبة للأمريكيين؛ حيث استسلم القادة الفلبينيون في عام 1901م، بعد معارك طاحنة أظهروا فيها ضروبًا من الاستبسال.

الحقبة الأمريكية

تميزت فترة الحكم الأمريكيّ بالجهود الرامية إلى نشر التعليم بين المواطنين، وتحسين المرافق الصحية والإنمائية، والعمل على إعداد أهل البلاد للاستقلال، وذلك بإصدار العديد من القوانين، مثل قانون انتخاب مجلس (كومنولث) في عام 1935م بوصفه خطوة أولى نحو الاستقلال، وكذلك أدخلوا المذهب النصراني البروتستانتي في البلاد.

عطل الغزو الياباني للفلبين عام 1941م واحتلال البلاد عام 1942م حركة المطالبة بالاستقلال، إذ أقام اليابانيون حكومة عسكرية حلّت الأحزاب السياسية، فواجهها أهل البلاد بمقاومة عنيفة اتخذت شكل حرب عصابات. وفي غمرة هذه الحروب تمكنّ الأمريكيون من العودة للفلبين حيث حاربوا اليابانيين وتغلبوا عليهم في 15 أغسطس 1945م. وفي 4 يوليو 1946م منح الأمريكيون أهل الفلبين استقلالهم، وقامت الجمهورية الفلبينية الثالثة. لكن البلاد كانت تعاني الفوضى السياسية والاقتصادية والاجتماعية.

كان على الرؤساء الفلبينيين بناء البلد من جديد، فاتّجه بعضهم إلى الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية لتساعد في بناء الفلبين مقابل اتفاقيات تعطيها قواعد عسكرية في أنحاء مختلفة من البلاد. وتوالى الرؤساء حتى عام 1965م، حيث تولى الرئاسة فرديناند ماركوس الذي اهتم بالإصلاح الإداري، وبتحسين علاقاته مع جيرانه في بداية عهده. لكن المشاكل الاقتصادية، وارتفاع الأسعار والفساد السياسي والاقتصادي كانت تحيط به من كل جانب، وسبّبت لحكمه الكثير من عدم الاستقرار حتى بعد إعادة انتخابه في عام 1969م، إذ فشلت إصلاحاته الزراعية، وازدادت الاضطرابات ومظاهرات الطلاب، فشهدت البلاد حدوث ثورة شيوعية، وكذلك انتفاضة العناصر المسلمة بالإضافة إلى الكوارث الطبيعية مثل الفيضانات. وقد أضافت كل هذه الأحداث مشاكل جديدة لماركوس، وجعلته يعلن حالة الطوارئ في سبتمبر 1972م، وكذلك الأحكام العرفية في محاولة لمعالجة مشاكله التي مافتئت تتفاقم وتنعكس سلبًا على اقتصاد البلاد، الذي أضعفته ثورات الشيوعيين، ونشاط حركة تحرير المورو الإسلامية. كما أن النزاع الطبقي بين القلة الغنية، والكثرة المعدمة شلَّ حركة المجتمع، وأكسب نظام ماركوس سمعة عدم احترامه لحقوق الإنسان كاغتيال أكينو زعيم المعارضة.

رفض ماركوس التنازل عن السلطة رغمًا عن فوز زعيمة المعارضة كورازون أكينو، أرملة أكينو، في انتخابات فبراير 1986م، ونتج عن ذلك ثورة شعبية أزاحته عن السلطة، ووضعت كورازون أكينو أول امرأة رئيسة فلبينية للبلاد في 25 فبراير 1986م.

تميزّ عهد أكينو بإجازة الدستور، وبمحاربة الفساد، ولكنها كانت محاطة بالمشاكل، مثل انتفاضة المسلمين، ومعارضة العناصر اليمينية، ومحاولات الانقلاب المتعددة، ثم الكوارث الطبيعية من براكين وفيضانات، وكانت حاجتها للمال شديدة لمواجهة تلك المشاكل التي أثّرت سلبًا على حكمها. وفي مايو 1992م، انتخب فيدل راموس رئيسًا للبلاد. كان راموس قد عمل ضمن حكومة ماركوس ولكنه ساعد أكينو في الإطاحة به ثم عمل وزيرًا للدفاع في حكومتها. وفي عام 1994م، عمل راموس على تعزيز مكانته السياسية فشكل حكومة إئتلافية خاض بها الانتخابات في العام التالي، وحصل على 75% من أصوات الناخبين. وفي 2 سبتمبر 1996م، وقع الرئيس راموس اتفاقية سلام مع نور ميسواري زعيم جبهة تحرير المورو الإسلامية بعد 24 عامًا من حرب أهلية أسفرت عن مصرع 120 ألف نسمة. ويفتح هذا الاتفاق الطريق أمام إنشاء دولة مسلمة مستقلة في جنوب الفليبين. وفي عام 1998م، انتخب جوزيف إسترادا رئيسًا للبلاد. وفي أكتوبر 2000م، واجه إسترادا دعوات يومية من عدة جهات تطالب باستقالته والتحقيق معه بعد أن اتهمه البعض بتلقي رشى بلغت ملايين الدولارات من نقابات قمار غير قانونية. وقد أصرت نائبة الرئيس جلوريا ماكاباجال على استقالة إسترادا لتفادي أزمة اقتصادية تضر بالبلاد. وفي يناير 2001م، استقال إسترادا وأصبحت جلوريا رئيسة للبلاد. وفي أبريل 2001م، تم اعتقال إسترادا بعد اتهامه باختلاس 80 مليون دولار إبان فترة حكمه، وقد رفض أنصاره تهم الفساد الموجهة لإسترادا.

انظر ايضا

- Communications History of the Philippines

- Transportation History of the Philippines

- Demographic History of the Philippines

- Military History of the Philippines

- Timeline of Philippine History

- Philippine Nationalism

ملاحظات

- ^ Ingicco, T.; van den Bergh, G.D.; Jago-on, C.; Bahain, J.-J.; Chacón, M.G.; Amano, N.; Forestier, H.; King, C.; Manalo, K.; Nomade, S.; Pereira, A.; Reyes, M.C.; Sémah, A.-M.; Shao, Q.; Voinchet, P.; Falguères, C.; Albers, P.C.H.; Lising, M.; Lyras, G.; Yurnaldi, D.; Rochette, P.; Bautista, A.; de Vos, J. (May 1, 2018). "Earliest known hominin activity in the Philippines by 709 thousand years ago". Nature. 557 (7704): 233–237. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..233I. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0072-8. PMID 29720661. S2CID 13742336.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:5 - ^ Severino, Howie (August 1, 2010). "Researchers discover fossil of human older than Tabon Man". GMA News Online (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ Jett, Stephen C. (2017). Ancient Ocean Crossings: Reconsidering the Case for Contacts with the Pre-Columbian Americas. University of Alabama Press. pp. 168–171. ISBN 9780817319397.

- ^ Détroit, Florent; Corny, Julien; Dizon, Eusebio Z.; Mijares, Armand S. (2013). ""Small Size" in the Philippine Human Fossil Record: Is It Meaningful for a Better Understanding of the Evolutionary History of the Negritos?" (PDF). Human Biology. 85 (1): 45–66. doi:10.3378/027.085.0303. PMID 24297220. S2CID 24057857. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-23.

- ^ Détroit, Florent; Mijares, Armand Salvador; Corny, Julien; Daver, Guillaume; Zanolli, Clément; Dizon, Eusebio; Robles, Emil; Grün, Rainer; Piper, Philip J. (April 2019). "A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines" (PDF). Nature. 568 (7751): 181–186. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..181D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9. PMID 30971845. S2CID 106411053.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:3 - ^ Reid, Lawrence A. (2007). "Historical linguistics and Philippine hunter-gatherers". In L. Billings; N. Goudswaard (eds.). Piakandatu ami Dr. Howard P. McKaughan. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL Philippines. pp. 6–32.

The Negrito groups are considered to be the earliest inhabitants of the Philippines... genetic evidence (the occurrence of unique alleles) suggests that the Negrito groups in Mindanao may have been separated from those in Luzon for twenty to thirty thousand years (p.10).

- ^ Scott 1984, p. 138. "Not one roof beam, not one grain of rice, not one pygmy Negrito bone has been recovered. Any theory which describes such details is therefore pure hypothesis and should be honestly presented as such."

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:6 - ^ أ ب ت Chambers, Geoff (2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians". eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ Mijares, Armand Salvador B. (2006). "The Early Austronesian Migration To Luzon: Perspectives From The Peñablanca Cave Sites". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association (26): 72–78. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014.

- ^ أ ب Bellwood, Peter (2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. p. 213.

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Loh, Po-Ru; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Ko, Ying-Chin; Stoneking, Mark; Berger, Bonnie; Reich, David (2014). "Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 4689. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5E4689L. doi:10.1038/ncomms5689. PMC 4143916. PMID 25137359.

- ^ Scott 1984, p. 52.

- ^ Goodenough, Ward Hunt (1996). Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, Volume 86, Part 5. American Philosophical Society. pp. 127–128.

- ^ Goodenough, Ward Hunt (1996). Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, Volume 86, Part 5. American Philosophical Society. p. 52.

- ^ "Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum". Archived from the original on February 28, 2014.

- ^ Sagart, Laurent (25 July 2008). "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia: a linguistic and archaeological model". In Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Peiros, Ilia; Lin, Marie (eds.). Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. Routledge. pp. 165–190. ISBN 978-1-134-14962-9.

- ^ Li, H; Huang, Y; Mustavich, LF; et al. (November 2007). "Y chromosomes of prehistoric people along the Yangtze River". Hum. Genet. 122 (3–4): 383–8. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0407-2. PMID 17657509. S2CID 2533393.

- ^ Ko, Albert Min-Shan; Chen, Chung-Yu; Fu, Qiaomei; Delfin, Frederick; Li, Mingkun; Chiu, Hung-Lin; Stoneking, Mark; Ko, Ying-Chin (March 2014). "Early Austronesians: Into and Out Of Taiwan". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 94 (3): 426–436. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.003. PMC 3951936. PMID 24607387.

- ^ أ ب Bellwood, Peter (2004). "The origins and dispersals of agricultural communities in Southeast Asia" (PDF). In Glover, Ian; Bellwood, Peter (eds.). Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 21–40. ISBN 9780415297776.

- ^ Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2012). "Emergence of social inequality – The middle Neolithic (5000–3000 BC)". The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139015301.007. ISBN 9780521644327.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- ^ Larena, Maximilian; Sanchez-Quinto, Federico; Sjödin, Per; McKenna, James; Ebeo, Carlo; Reyes, Rebecca; Casel, Ophelia; Huang, Jin-Yuan; Hagada, Kim Pullupul; Guilay, Dennis; Reyes, Jennelyn; Allian, Fatima Pir; Mori, Virgilio; Azarcon, Lahaina Sue; Manera, Alma; Terando, Celito; Jamero, Lucio; Sireg, Gauden; Manginsay-Tremedal, Renefe; Labos, Maria Shiela; Vilar, Richard Dian; Latiph, Acram; Saway, Rodelio Linsahay; Marte, Erwin; Magbanua, Pablito; Morales, Amor; Java, Ismael; Reveche, Rudy; Barrios, Becky; Burton, Erlinda; Salon, Jesus Christopher; Kels, Ma. Junaliah Tuazon; Albano, Adrian; Cruz-Angeles, Rose Beatrix; Molanida, Edison; Granehäll, Lena; Vicente, Mário; Edlund, Hanna; Loo, Jun-Hun; Trejaut, Jean; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Reid, Lawrence; Malmström, Helena; Schlebusch, Carina; Lambeck, Kurt; Endicott, Phillip; Jakobsson, Mattias (30 March 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (13): e2026132118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- ^ Legarda, Benito, Jr. (2001). "Cultural Landmarks and their Interactions with Economic Factors in the Second Millennium in the Philippines". Kinaadman (Wisdom) A Journal of the Southern Philippines. 23: 40.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Munoz, Paul Michael (2006). Early kingdoms of the Indonesian archipelago and the Malay peninsula. p. 45.

- ^ Glover, Ian; Bellwood, Peter, eds. (2004). Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. Psychology Press. pp. 36, 157. ISBN 978-0-415-29777-6.

- ^ The Philippines and India – Dhirendra Nath Roy, Manila 1929 and India and The World – By Buddha Prakash p. 119–120.

- ^ Hsiao-Chun Hung, et al. (2007). Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia. PNAS.

- ^ Father Gabriel Casal & Regalado Trota Jose, Jr., Eric S. Casino, George R. Ellis, Wilhelm G. Solheim II, The People and Art of the Philippines, printed by the Museum of Cultural History, UCLA (1981)

- ^ Bellwood, Peter, Hsiao-Chun Hung, and Yoshiyuki Iizuka. "Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction." Paths of Origins: The Austronesian Heritage in the Collections of the National Museum of the Philippines, the Museum Nasional Indonesia, and the Netherlands Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde (2011): 31-41.

- ^ Scott 1984, p. 17.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter (2011). Pathos of Origin. pp. 31–41.

- ^ Hsiao-Chun, Hung (2007). Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia.

- ^ Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000), "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan", Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 20: 153–158, doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751

- ^ Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan’s relations with the Philippines date back millenia, so it’s a mystery that it’s not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- ^ Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- ^ Bellwood, P., H. Hung, H., Lizuka, Y. (2011). Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction. Semantic Scholar.

- ^ Mallari, P. G. S. (2014). War and peace in precolonial Philippines. The Manila Times.

- ^ Junker, L. L. (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ Solheim, William (1969). "Prehistoric Archaeology in Eastern Mainland Southeast Asia and the Philippines". Asian Perspectives. 3: 97–108. hdl:10125/19126.

- ^ Miksic, John N. (2003). Earthenware in Southeast Asia: Proceedings of the Singapore Symposium on Premodern Southeast Asian Earthenwares. Singapore: Singapore University Press, National University of Singapore.

- ^ Dhani Irwanto (2019). Sundaland: Tracing The Cradle of Civilizations. Indonesia Hydro Media. p. 41. ISBN 978-602-724-493-1.

- ^ Yamagata, Mariko; Matsumura, Hirofumi (2017), Matsumura, Hirofumi; Piper, Philip J.; Bulbeck, David, eds., Austronesian Migration to Central Vietnam:: Crossing over the Iron Age Southeast Asian Sea, 45, ANU Press, pp. 333–356, ISBN 978-1-76046-094-5

المصادر

- Agoncillo, Teodoro C. (1990) [1960], History of the Filipino People (8th ed.), Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, ISBN 971-8711-06-6

- Columbia University Press (2001). "Philippines, The". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Bartleby.com.

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-3), "Early History", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/3.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-4), "The Early Spanish", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/4.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-5), "The Decline of Spanish", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/5.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-13), "Spanish American War", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/13.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-15), "War of Resistance", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/15.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-16), "United States Rule", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/16.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-17), "A Collaborative Philippine Leadership", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/17.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-20), "Commonwealth Politics", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/20.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-21), "World War II", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/21.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-23), "Economic Relations with the United States", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/23.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-26), "The Magsaysay, Garcia, and Macapagal Administrations", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/26.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-27), "Marcos and the Road to Martial Law", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/27.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-28), "Proclamation 1081 and Martial Law", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/28.htm

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-29), "From Aquino's Assassination to People Power", Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, ISBN 0844407488, http://countrystudies.us/philippines/29.htm

- Riggs, Fred W. (1994), "Bureaucracy: A Profound Puzzle for Presidentialism", in Farazmand, Ali, Handbook of Bureaucracy, CRC Press, http://books.google.com.ph/books?id=8NBc_QT26ZoC&pg=PA97 ISBN 0824791827, ISBN 9780824791827.

- Fish, Shirley (2003), When Britain Ruled The Philippines 1762-1764, 1stBooks, ISBN 1410710696, http://books.google.com/books?id=4goyHgAACAAJ

- Lacsamana, Leodivico Cruz (1990), Philippine History and Government (Second ed.), Phoenix Publishing House, Inc., ISBN 9710618946

- Tracy, Nicholas (1995), Manila Ransomed: The British Assault on Manila in the Seven Years War, University of Exeter Press, http://books.google.com/books?id=AoNxAAAAMAAJ ISBN 0859894266, ISBN 9780859894265

- Stearns, Peter N., ed. (2002), "V.(F)2. The Philippines, 1800–1913", Encyclopedia of World History, Bartleby.com, http://www.bartleby.com/67/toc5.html, retrieved on 2008-08-09

- Woods, Ayon kay Damon L. (2005), The Philippines, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1851096752, http://books.google.com.ph/books?id=2Z-n_kDTxf0C

- Zaide, Sonia M. (1994), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing Co., ISBN 971-642-071-4

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

قراءات اخرى

- Corpuz, O.D. (2005), Roots of the Filipino Nation, University of the Philippines Press, http://www.amazon.com/Roots-Filipino-Nation-O-Corpuz/dp/9715424600

- Millis, Walter (1931), The Martial Spirit, Houghton Mifflin Company, http://books.google.com/books?id=dJkuAAAAIAAJ&pgis=1

- Worcester, Dean Conant (1913). The Philippines: Past and Present. New York: The Macmillan company.

- Worcester, Dean Conant (1898). The Philippine Islands and Their People.

وصلات خارجية

- Official government portal of the Republic of the Philippines.

- National Histroical Institute.

- The United States and its Territories 1870–1925: The Age of Imperialism.

- Origins of the Filipinos and Their Languages by Wilhelm G. Solheim II (PDF).

- History of the Philippine Islands by Morga, Antonio de in 55 volumes, from Project Gutenberg. Translated into English, edited and annotated by E. H. Blair and J. A. Robertson. Volumes 1-14 and 15-25 indexed under Blair, Emma Helen.

- Philippine Society and Revolution.

- The Brown Raise Movement - contains social commentaries by Jose Rizal, Apolinario Mabini, and F. Sionil Jose